Simvastatin Improves the High-Fat-Diet-Induced Metabolic Disorder in Juvenile Chinese Giant Salamander (Andrias davidianus) Through Inhibiting Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Enhancing Mitochondrial Function

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Diets, Animals, and the Feeding Trial

2.2. Sampling

2.3. Proximate Composition Analysis

2.4. Plasma Biochemical Parameters Analysis

2.5. Gene Expression

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

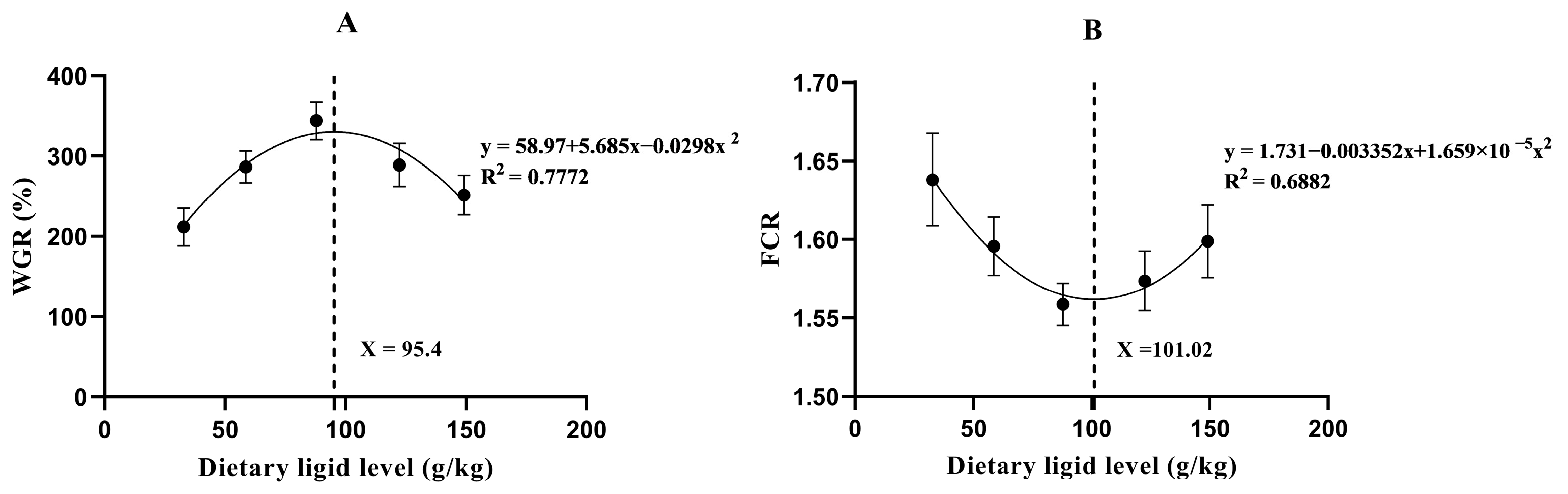

3.1. Experiment I: Evaluation of the Optimal Lipid Requirement

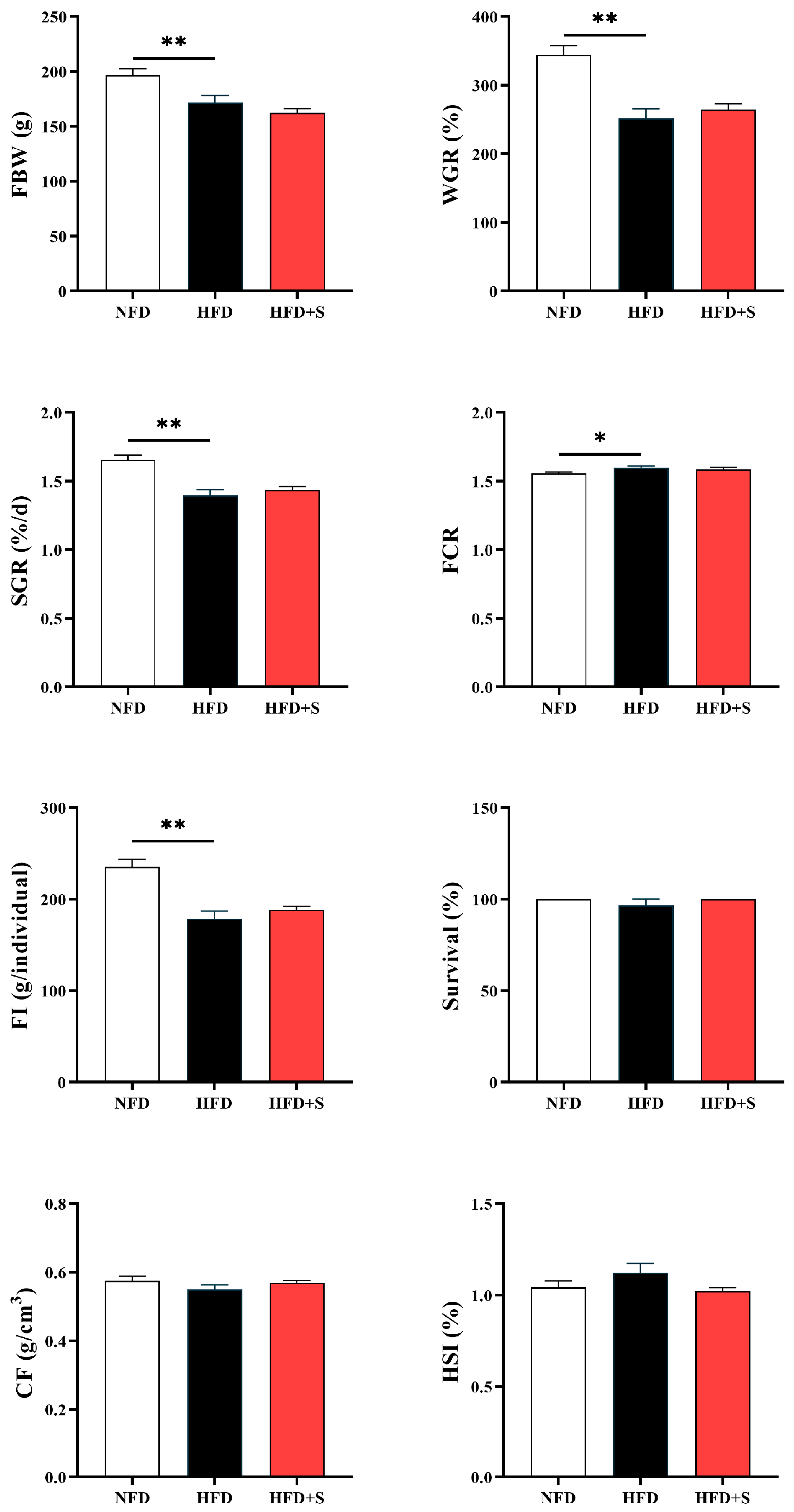

3.2. Experiment II: Investigating the Regulatory Effects of Simvastatin in Metabolic Disorder

3.2.1. Growth Performance

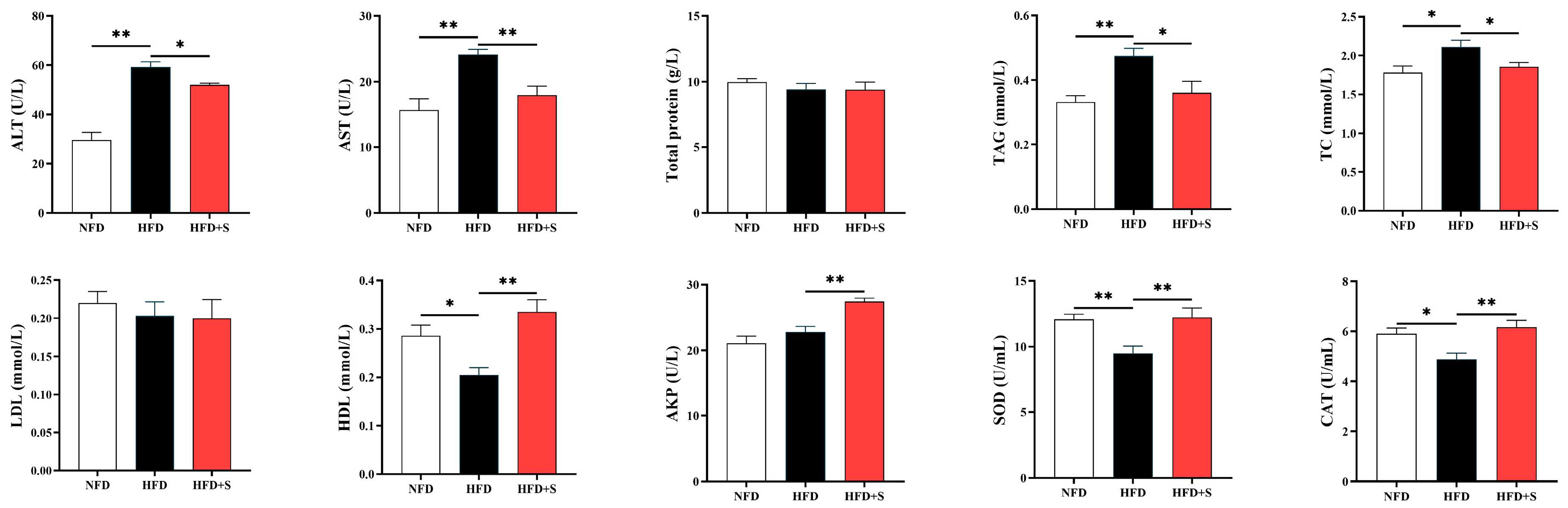

3.2.2. Plasma Biochemical Analysis

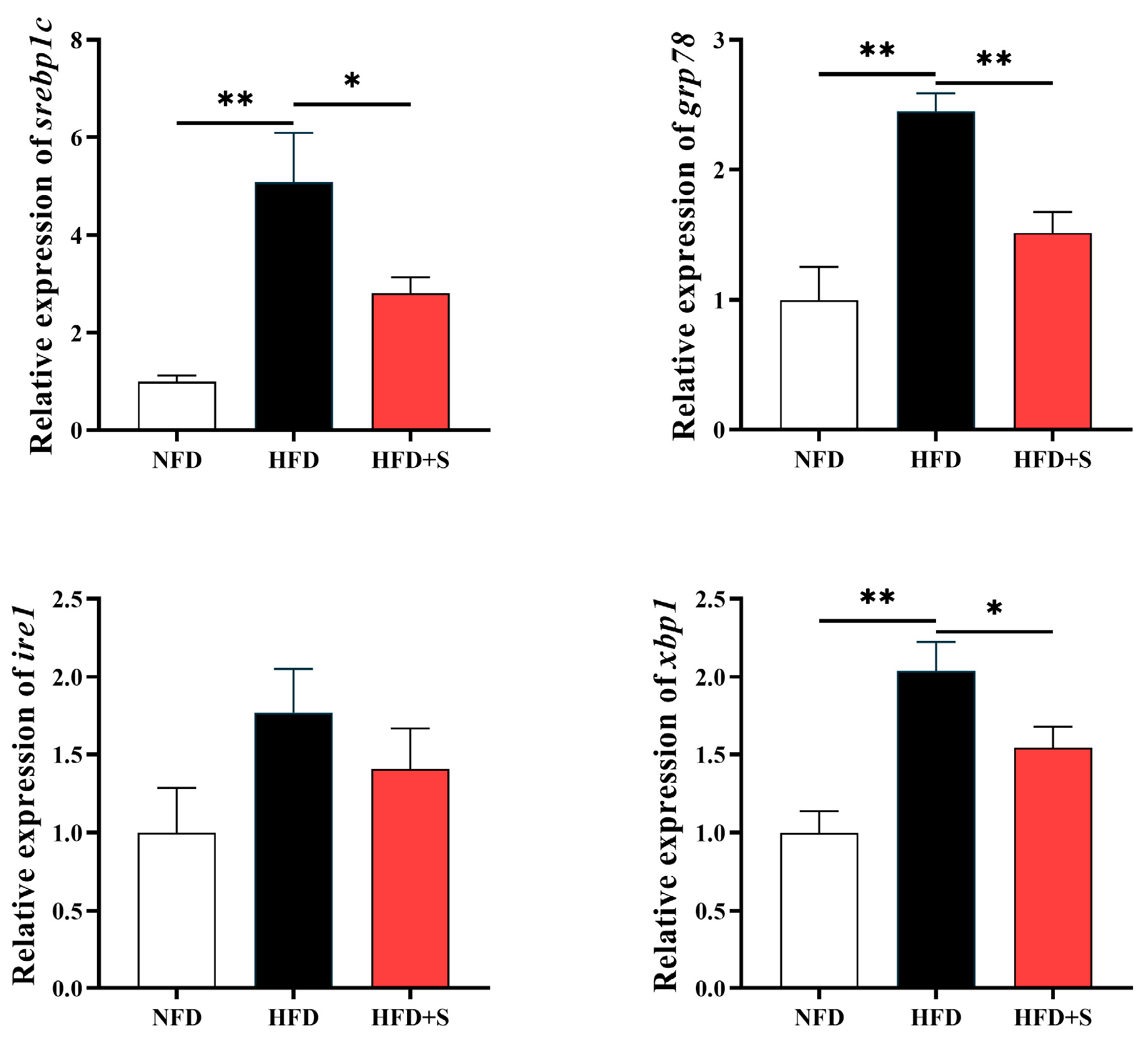

3.2.3. Hepatic Expressions of Genes Related to Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress

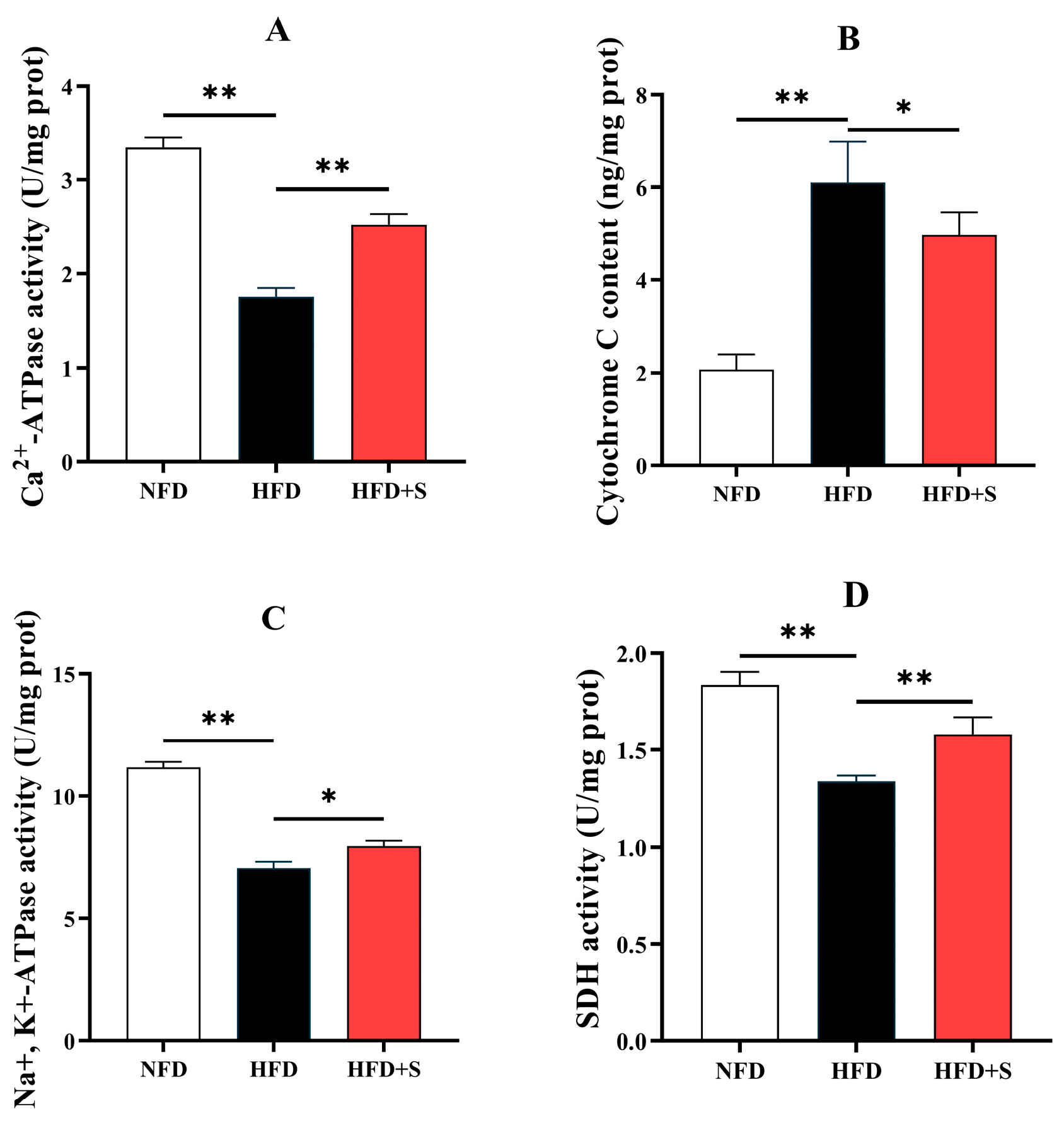

3.2.4. Mitochondrial Function-Related Indices

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pyron, R.A.; Wiens, J.J. A large-scale phylogeny of Amphibia including over 2800 species, and a revised classification of extant frogs, salamanders, and caecilians. Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 2011, 61, 543–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Fan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Meng, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Xue, M.; Robert, J.; Zeng, L. The Immune System and the Antiviral Responses in Chinese Giant Salamander, Andrias davidianus. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 718624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, D.; Zhu, W.; Zeng, W.; Lin, J.; Ji, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, D.; Su, N. Nutritional and medicinal characteristics of Chinese giant salamander (Andrias davidianus) for applications in healthcare industry by artificial cultivation: A review. Food Sci. Hum. Well. 2018, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, A.A.; Turvey, S.T.; Zhou, F.; Meredith, H.M.R.; Guan, W.; Liu, X.; Sun, C.; Wang, Z.; Wu, M. Development of the Chinese giant salamander Andrias davidianus farming industry in Shaanxi Province, China: Conservation threats and opportunities. Oryx 2016, 50, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Feng, Q.; Zhang, H.; Huang, X.; Luo, L. Effects of dietary mulberry leaf extract on the growth, gastrointestinal, hepatic functions of Chinese giant salamander (Andrias davidianus). Aquacult. Res. 2020, 51, 2613–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akintan, O.; Gebremedhin, K.G.; Uyeh, D.D. Animal Feed Formulation—Connecting Technologies to Build a Resilient and Sustainable System. Animals 2024, 14, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.Z.; Wei, Y.; Wang, L.; Song, K.; Zhang, C.X.; Lu, K.L.; Rahimnejad, S. Dietary n-3/n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid ratio modulates growth performance in spotted seabass (Lateolabrax maculatus) through regulating lipid metabolism, hepatic antioxidant capacity and intestinal health. Anim. Nutr. 2023, 14, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.-H.; Lin, Y.; Pan, W.-J.; Huang, X.; Ge, X.-P.; Liu, B.; Ren, M.-C.; Zhou, Q.-L.; Pan, L.-K. MiR-34a regulates the glucose metabolism of Blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) fed high-carbohydrate diets through the mediation of the Sirt1/FoxO1 axis. Aquaculture 2019, 500, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Cao, L.-P.; Du, J.-L.; He, Q.; Gu, Z.-Y.; Jeney, G.; Xu, P.; Yin, G.-J. Effects of High-Fat Diet on Steatosis, Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Autophagy in Liver of Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, A.A.; Voeltz, G.K. Endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria contacts: Function of the junction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 607–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.-Z.; Xia, T.; Lin, J.-B.; Wang, L.; Song, K.; Zhang, C.-X. Quercetin Attenuates High-Fat Diet-Induced Excessive Fat Deposition of Spotted Seabass (Lateolabrax maculatus) Through the Regulatory for Mitochondria and Endoplasmic Reticulum. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 746811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanders, R.J.; Waterham, H.R.; Ferdinandusse, S. Metabolic Interplay between Peroxisomes and Other Subcellular Organelles Including Mitochondria and the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 3, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.F.; Dai, Y.J.; Liu, M.Y.; Yuan, X.Y.; Wang, C.C.; Huang, Y.Y.; Liu, W.B.; Jiang, G.Z. High-fat diet induces aberrant hepatic lipid secretion in blunt snout bream by activating endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated IRE1/XBP1 pathway. BBA-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2019, 1864, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.-F.; Liu, W.-B.; Zheng, X.-C.; Yuan, X.-Y.; Wang, C.-C.; Jiang, G.-Z. Effects of high-fat diets on growth performance, endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial damage in blunt snout bream Megalobrama amblycephala. Aquac. Nutr. 2019, 25, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, J.; Li, J.-S.; Chen, H.; Huang, K.; Zheng, L. Accumulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress and lipogenesis in the liver through generational effects of high fat diets. J. Hepatol. 2012, 56, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Dobs, A.; Yuan, Z.; Battisti, W.P.; Borisute, H.; Palmisano, J. Effectiveness of simvastatin therapy in raising HDL-C in patients with type 2 diabetes and low HDL-C. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2004, 20, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypiec-Spring, M.; Sapa-Wojciechowska, A.; Haczkiewicz-Leśniak, K.; Piasecki, T.; Kwiatkowska, J.; Podhorska-Okołów, M.; Szeląg, A. HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitor, Simvastatin Is Effective in Decreasing Degree of Myocarditis by Inhibiting Metalloproteinases Activation. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Alwabli, R.I.; Attwa, M.W.; Rahman, A.F.M.M.; Kadi, A.A. Simvastatin: In Vitro Metabolic Profiling of a Potent Competitive HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitor. Separations 2022, 9, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthwick, F.; Mangat, R.; Warnakula, S.; Jacome-Sosa, M.; Vine, D.F.; Proctor, S.D. Simvastatin treatment upregulates intestinal lipid secretion pathways in a rodent model of the metabolic syndrome. Atherosclerosis 2014, 232, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Fan, X.; Ye, R.; Hu, Y.; Zheng, T.; Shi, R.; Cheng, W.; Lv, X.; Chen, L.; Liang, P. The Effect of Simvastatin on Gut Microbiota and Lipid Metabolism in Hyperlipidemic Rats Induced by a High-Fat Diet. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M.; Pan, T.; Tocher, D.R.; Betancor, M.B.; Monroig, Ó.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, T.; Sun, P.; Jiao, L.; Zhou, Q. Dietary choline supplementation attenuated high-fat diet-induced inflammation through regulation of lipid metabolism and suppression of NFκB activation in juvenile black seabream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii). J. Nutri. Sci. 2019, 8, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-h.; Pan, Y.-x.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.-l.; Huang, X.-q.; Zhong, Y.-w.; Tang, T.; Zhang, J.-s.; Chu, W.-y.; Shen, Y.-d. Effects of high-fat diet on muscle textural properties, antioxidant status and autophagy of Chinese soft-shelled turtle (Pelodiscus sinensis). Aquaculture 2019, 511, 734228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompili, S.; Vetuschi, A.; Gaudio, E.; Tessitore, A.; Capelli, R.; Alesse, E.; Latella, G.; Sferra, R.; Onori, P. Long-term abuse of a high-carbohydrate diet is as harmful as a high-fat diet for development and progression of liver injury in a mouse model of NAFLD/NASH. Nutrition 2020, 75–76, 110782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 18th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.-J.; Choi, Y.-K.; Im, H.-S.; Yarimaga, O.; Yoon, E.; Kim, H.-S. Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST/GOT) and Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT/GPT) Detection Techniques. Sensors 2006, 6, 756–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Luo, L.; Wu, X.; Ren, Z.; Gao, P.; Yu, Y.; Pearl, G. Effects of six alternative lipid sources on growth and tissue fatty acid composition in Japanese sea bass (Lateolabrax japonicus). Aquaculture 2006, 260, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Pan, L.; Yu, J.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhai, X.; Xue, Y.; Luo, L. Effects of dietary lipid levels on growth, antioxidant capacity, intestinal and liver structure of juvenile giant salamander (Andrias davidianus). Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1515014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, L.A.; Coyle, S.D.; Tidwell, J.H. Effect of dietary lipid level and protein energy ratio on growth and body composition of largemouth bass Micropterus salmoides. J. World Aquacult. Soc. 2005, 36, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, W.; Ge, X. Protein-sparing effect of dietary lipid in practical diets for blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) fingerlings: Effects on digestive and metabolic responses. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 38, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.M.; Cao, F.; Huang, H.Y.R.; Chen, L.; Chen, Y.; Gong, R.; Raptis, A.; Creasy, K.T.; Clusmann, J.; van Haag, F.; et al. The Lipidomic Profile Discriminates Between MASLD and MetALD. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 61, 1357–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, T.R.; Tobert, J.A. Simvastatin: A review. Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2004, 5, 2583–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yan, K.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; He, Y.; Wang, E.; Wang, G. Dietary sanguinarine enhances disease resistance to Aeromonas dhakensis in largemouth (Micropterus salmoides). Fish. Shellfish. Immunol. 2025, 165, 110577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Zhu, N.; Xu, R.; Wangkahart, E.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.; Wang, R.; Xu, Z.; Kong, W.; Xu, H. Comparative analysis on antioxidant capacity, immunity and histopathological changes of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) in response to mono- or co-infection with Aeromonas veronii and Nocardia seriolae. Fish. Shellfish. Immunol. 2025, 167, 110886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Vikash, V.; Ye, Q.; Wu, D.; Liu, Y.; Dong, W. ROS and ROS-Mediated Cellular Signaling. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 4350965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Abramov, A.Y. The emerging role of Nrf2 in mitochondrial function. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2015, 88, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, A.; Reiner, Ž.; Ruscica, M.; Tedeschi-Reiner, E.; Radbakhsh, S.; Bagheri Ekta, M.; Sahebkar, A. Antioxidant Effects of Statins by Modulating Nrf2 and Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling in Different Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress responses. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 862–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, S.; Watkins, S.M.; Hotamisligil, G.S. The Role of Endoplasmic Reticulum in Hepatic Lipid Homeostasis and Stress Signaling. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, B.M.; Pincus, D.; Gotthardt, K.; Gallagher, C.M.; Walter, P. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Sensing in the Unfolded Protein Response. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, 13169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, J.D.; Goldstein, J.L.; Brown, M.S. SREBPs: Activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 109, 1125–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürgens, F.M.; Behrens, M.; Humpf, H.-U.; Robledo, S.M.; Schmidt, T.J. In Vitro Metabolism of Helenalin Acetate and 11α,13-Dihydrohelenalin Acetate: Natural Sesquiterpene Lactones from Arnica. Metabolites 2022, 12, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakka, V.P.; Prakash-Babu, P.; Vemuganti, R. Crosstalk Between Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress, Oxidative Stress, and Autophagy: Potential Therapeutic Targets for Acute CNS Injuries. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 532–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oezcan, U.; Yilmaz, E.; Oezcan, L.; Furuhashi, M.; Vaillancourt, E.; Smith, R.O.; Goerguen, C.Z.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Chemical chaperones reduce ER stress and restore glucose homeostasis in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Science 2006, 313, 1137–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousuf, M.S.; Maguire, A.D.; Simmen, T.; Kerr, B.J. Endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria interplay in chronic pain: The calcium connection. Mol. Pain. 2020, 16, 1744806920946889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addabbo, F.; Montagnani, M.; Goligorsky, M.S. Mitochondria and Reactive Oxygen Species. Hypertension 2009, 53, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begriche, K.; Massart, J.; Robin, M.-A.; Bonnet, F.; Fromenty, B. Mitochondrial Adaptations and Dysfunctions in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatology 2013, 58, 1497–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ingredients 1 | Dietary Lipid Levels (g/kg) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32.8 | 58.7 | 87.9 | 122.4 | 149.2 | |

| Fish meal | 210 | 210 | 210 | 210 | 210 |

| Soybean meal | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| Casein | 166.3 | 166.3 | 166.3 | 166.3 | 166.3 |

| Gelatin | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Wheat middling | 180 | 149.1 | 118.3 | 87.4 | 56.6 |

| Gelatinized starch | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 |

| Soybean oil | 1.35 | 16.8 | 32.2 | 47.65 | 63.05 |

| Fish oil | 1.35 | 16.8 | 32.2 | 47.65 | 63.05 |

| Choline chloride | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Calcium biphosphate | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| Premix 2 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Proximate composition | |||||

| Moisture | 95.2 | 97.4 | 96.3 | 94.7 | 95.1 |

| Crude protein | 448.7 | 453.5 | 452.2 | 449.4 | 451.4 |

| Crude lipid | 32.8 | 58.7 | 87.9 | 122.4 | 149.2 |

| Ash | 97.4 | 94.2 | 98.7 | 100.2 | 95.8 |

| Ingredients | Groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| NFD | HFD | HFD_S | |

| Fish meal | 210 | 210 | 210 |

| Soybean meal | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| Casein | 166.3 | 166.3 | 166.3 |

| Gelatin | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Wheat middling | 118.3 | 56.6 | 56.5 |

| Gelatinized starch | 150 | 150 | 150 |

| Soybean oil | 32.2 | 63.05 | 63.05 |

| Fish oil | 32.2 | 63.05 | 63.05 |

| Choline chloride | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Calcium biphosphate | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| Premix | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Simvastatin | 0 | 0 | 0.1 |

| Proximate composition | |||

| Moisture | 95.7 | 94.8 | 97.7 |

| Crude protein | 451.6 | 453.2 | 452.1 |

| Crude lipid | 86.8 | 148.4 | 147.3 |

| Ash | 96.8 | 97.7 | 96.5 |

| Gene Abbreviations | Gene Full Names | Primer Sequences (5′–3′) | Source | Amplicon Sizes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| srebp1c | sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c | ACTCGGTGTGGATATCGT | PRJNA1332065 | 105 bp |

| TGAACGCAATCTGGAAG | ||||

| grp78 | glucose-regulated protein 78 | TTACAGACCTTAGAGACTG | PRJNA1332065 | 122 bp |

| GGGGGTTGATCCACTCTAT | ||||

| ire1 | inositol-requiring enzyme 1 | ATCGAATCAGACGCTGACA | PRJNA1178345 | 155 bp |

| CCATCTGCACTCTAGCCATC | ||||

| xbp1 | x-box binding protein 1 | ACACGGCACTAGGGGCACTC | PRJNA1178345 | 107 bp |

| AGCTCATCGCTTGGATCTGGG | ||||

| β-actin | - | CTTGTATTCTCAGCAAGAC | HQ822274.1 | 135 bp |

| CATCTAGCCTCCATTACC |

| Parameters | Dietary Lipid Levels (g/kg) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32.8 | 58.7 | 87.9 | 122.4 | 149.2 | |

| FBW 1 | 137.56 ± 5.94 a | 171.37 ± 4.31 bc | 196.44 ± 6.25 c | 171.75 ± 6.3 bc | 155.28 ± 5.66 ab |

| WGR 2 | 211.87 ± 13.40 a | 286.99 ± 11.40 bc | 344.15 ± 13.70 c | 289.21 ± 15.48 bc | 251.77 ± 14.20 ab |

| SGR 3 | 1.26 ± 0.05 a | 1.50 ± 0.03 bc | 1.66 ± 0.03 c | 1.51 ± 0.04 bc | 1.40 ± 0.04 ab |

| FCR 4 | 1.64 ± 0.02 b | 1.60 ± 0.01 ab | 1.56 ± 0.01 a | 1.58 ± 0.01 a | 1.60 ± 0.01 ab |

| FI 5 | 153.26 ± 11.26 a | 202.69 ± 5.97 bc | 237.24 ± 9.24 c | 200.87 ± 10.61 bc | 177.56 ± 8.08 ab |

| Survival 6 | 96.67 ± 3.33 | 93.33 ± 3.33 | 96.67 ± 3.33 | 90.00 ± 5.77 | 96.67 ± 3.33 |

| CF 7 | 0.56 ± 0.01 | 0.56 ± 0.01 | 0.57 ± 0.01 | 0.55 ± 0.01 | 0.55 ± 0.02 |

| HSI 8 | 4.74 ± 0.15 a | 4.74 ± 0.12 a | 5.07 ± 0.12 ab | 5.30 ± 0.08 bc | 5.59 ± 0.09 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Dong, Y.; Du, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Simvastatin Improves the High-Fat-Diet-Induced Metabolic Disorder in Juvenile Chinese Giant Salamander (Andrias davidianus) Through Inhibiting Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Enhancing Mitochondrial Function. Animals 2026, 16, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010134

Wang Y, Chen J, Dong Y, Du J, Ma S, Wang H, Wang Y, Li X. Simvastatin Improves the High-Fat-Diet-Induced Metabolic Disorder in Juvenile Chinese Giant Salamander (Andrias davidianus) Through Inhibiting Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Enhancing Mitochondrial Function. Animals. 2026; 16(1):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010134

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yuheng, Jun Chen, Yanzou Dong, Jie Du, Sisi Ma, Huicong Wang, Yaoyue Wang, and Xiangfei Li. 2026. "Simvastatin Improves the High-Fat-Diet-Induced Metabolic Disorder in Juvenile Chinese Giant Salamander (Andrias davidianus) Through Inhibiting Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Enhancing Mitochondrial Function" Animals 16, no. 1: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010134

APA StyleWang, Y., Chen, J., Dong, Y., Du, J., Ma, S., Wang, H., Wang, Y., & Li, X. (2026). Simvastatin Improves the High-Fat-Diet-Induced Metabolic Disorder in Juvenile Chinese Giant Salamander (Andrias davidianus) Through Inhibiting Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Enhancing Mitochondrial Function. Animals, 16(1), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010134