Declining Abundance and Variable Condition of Fur Seal (Arctocephalus forsteri) Pups on the West Coast of New Zealand’s South Island

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Establish whether previously observed trends in New Zealand fur seal pup abundance and condition have continued.

- Examine the comparability of trends at the three study breeding colonies on the WCSI.

- Provide recommendations for future research to determine the causes of the observed population trends.

2. Methods

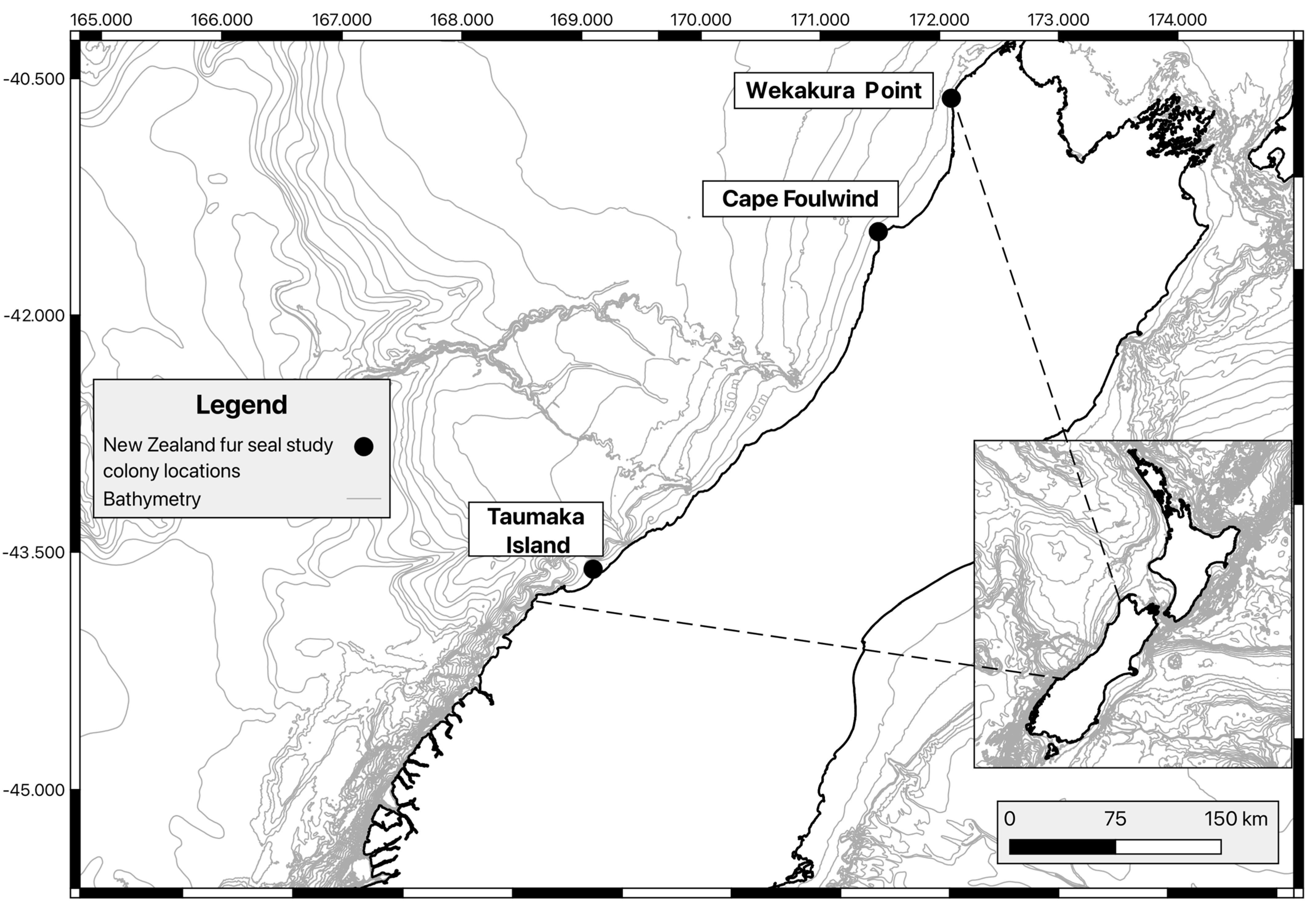

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Live Pup Abundance Estimates 2018–2025

2.3. Pup Condition Observations

2.4. Body Condition Index Calculations

2.5. Statistical Analyses

2.5.1. Effect of Year on Live Pup Abundances 1991/92–2025

2.5.2. Pan-Colony Pup Mass and Condition Models

2.5.3. Individual Colony Pup Mass and Condition Models

3. Results

3.1. Live Pup Abundance Estimates

3.2. Effects of Year on Live Pup Abundance Estimates

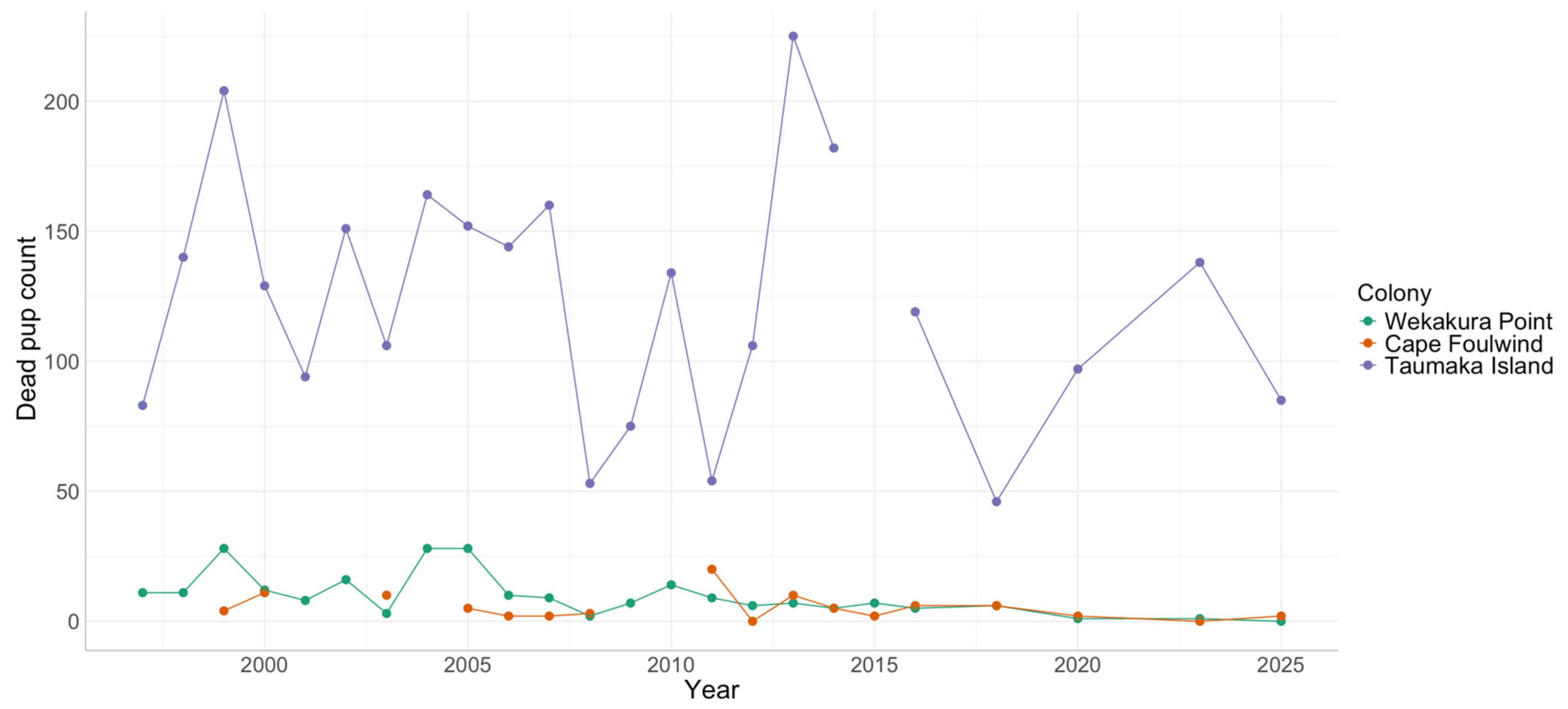

3.3. Dead Pup Counts

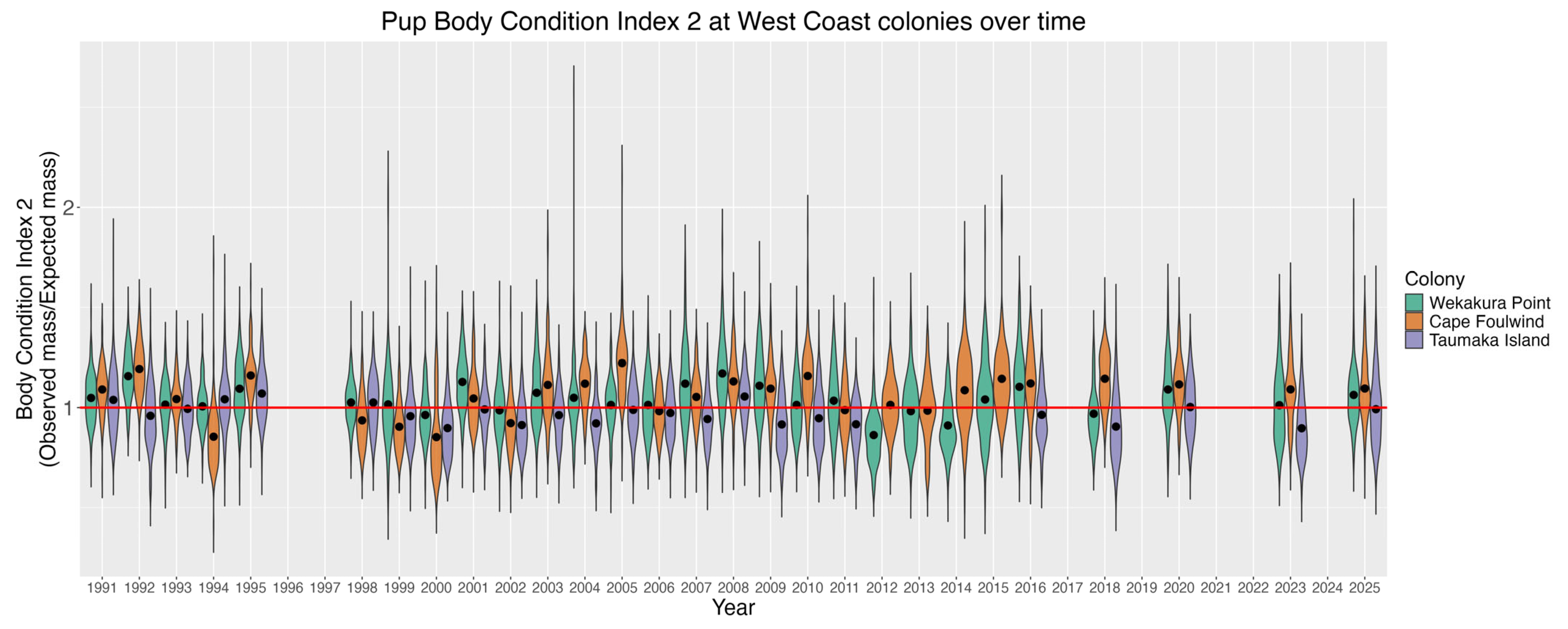

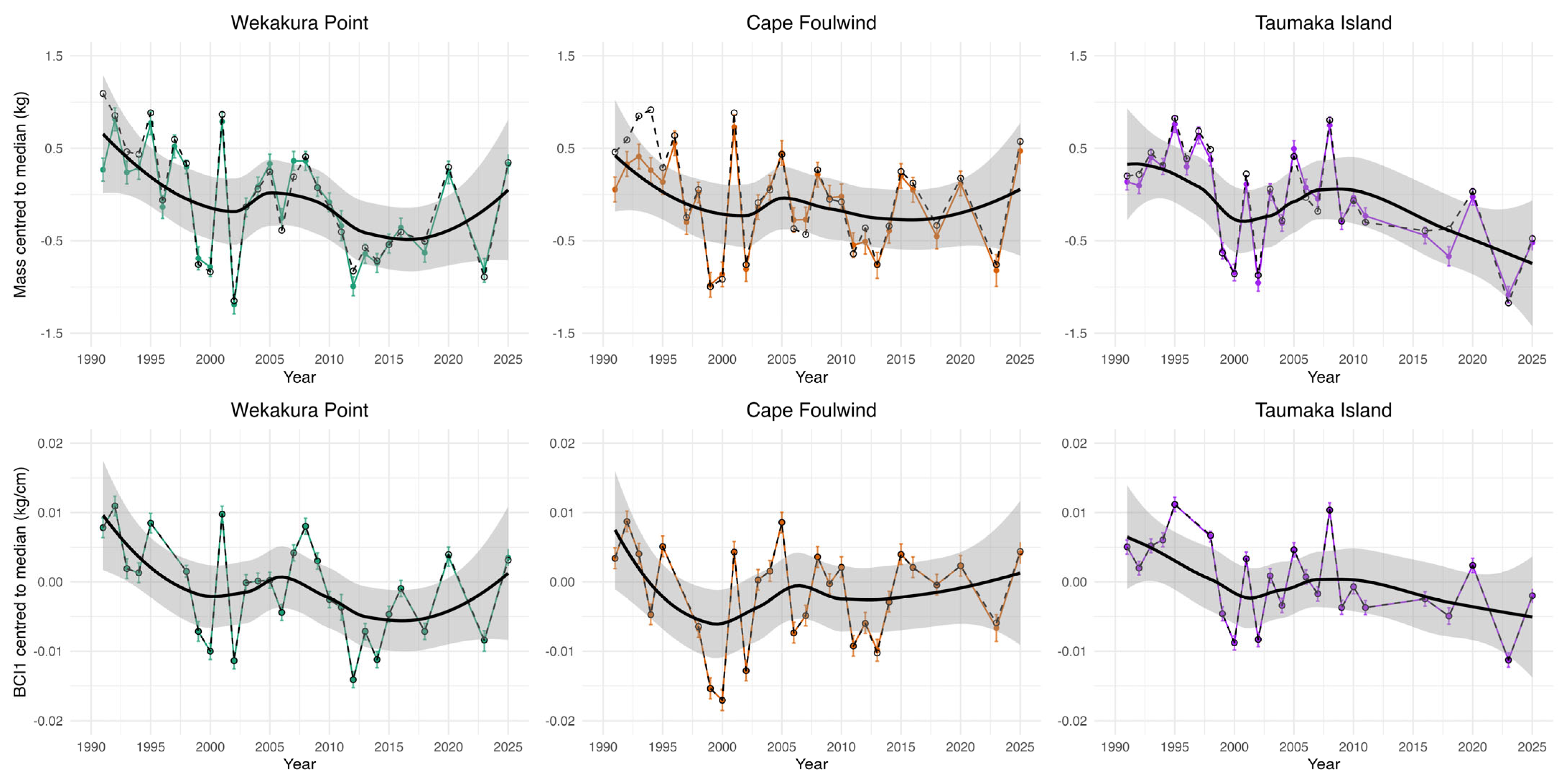

3.4. Pup Size and Condition

3.4.1. Pan-Colony Pup Mass and Condition Model Results

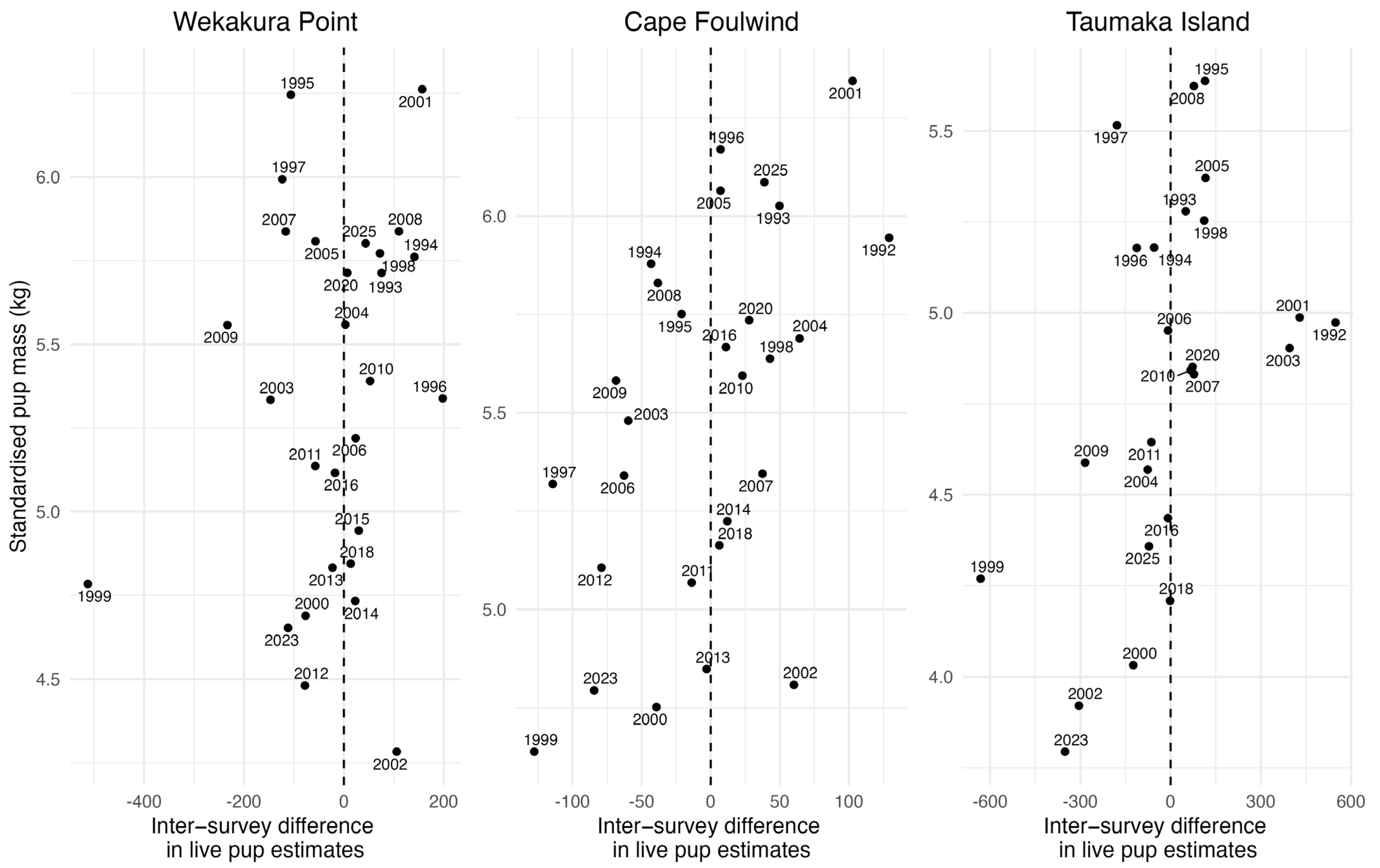

3.4.2. Individual Colony Pup Mass and Condition Model Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Potential Causes of the Colony Declines

4.1.1. Episodic Drops in Pup Abundance

4.1.2. Long-Term Declines in Breeding Colony Sizes

4.2. Recommendations for Future Monitoring and Research

4.2.1. Abundance and Health Monitoring

4.2.2. Diet and Foraging Studies

4.3. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ling, J.K. Exploitation of Fur Seals and Sea Lions from Australian, New Zealand and Adjacent Subantarctic Islands during the Eighteenth, Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Aust. Zool. 1990, 31, 323–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, R.; Pemberton, D.; Gales, R.; Hoskins, A.J.; Mitchell, T.; Shaughnessy, P.D.; Arnould, J.P.Y. Continued Population Recovery by Australian Fur Seals. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2010, 61, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, S.P.; Oosthuizen, W.H.; Meÿer, M.A.; Seakamela, S.M.; Underhill, L.G. Prioritising Range-Wide Scientific Monitoring of the Cape Fur Seal in Southern Africa. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 2011, 33, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, E.A.; Schiavini, A.C.M.; García, N.A.; Franco-Trecu, V.; Goodall, R.N.P.; Rodríguez, D.; Stenghel Morgante, J.; de Oliveira, L.R. Status, Population Trend and Genetic Structure of South American Fur Seals, Arctocephalus Australis, in Southwestern Atlantic Waters. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2015, 31, 866–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussex, N.; Robertson, B.C.; Salis, A.T.; Kalinin, A.; Best, H.; Gemmell, N.J. Low Spatial Genetic Differentiation Associated with Rapid Recolonization in the New Zealand Fur Seal Arctocephalus forsteri. J. Hered. 2016, 107, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, I.W. Historical Documents, Archaeology and 18th Century Seal Hunting in New Zealand. In Oceanic Culture History. Essays in Honour of Roger Green; New Zealand Journal of Archaeology Special Publication: Dunedin, New Zealand, 1996; pp. 675–688. [Google Scholar]

- Lalas, C.; Bradshaw, C.J.A. Folklore and Chimerical Numbers: Review of a Millennium of Interaction between Fur Seals and Humans in the New Zealand Region. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2001, 35, 477–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, O.; Spiller, L.C.; Campbell, R.; Hitchen, Y.; Kennington, W.J. Population Recovery of the New Zealand Fur Seal in Southern Australia: A Molecular DNA Analysis. J. Mammal. 2012, 93, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, V.N.; Grandi, M.F.; Schiavini, A.C.M.; Crespo, E.A. Sea Lions (Otaria flavescens) from the End of the World: Insights of a Recovery. Polar Biol. 2020, 43, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, V.N.; Grandi, M.F.; Schiavini, A.C.M.; Crespo, E.A. Recovery of South American Fur Seals from Fuegian Archipelago (Argentina). Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2020, 36, 1022–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcada, J.; Hoffman, J.I.; Gimenez, O.; Staniland, I.J.; Bucktrout, P.; Wood, A.G. Ninety Years of Change, from Commercial Extinction to Recovery, Range Expansion and Decline for Antarctic Fur Seals at South Georgia. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2023, 29, 6867–6887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, R.; Stainfield, C.; Fox-Clarke, C.; Toscani, C.; Forcada, J.; Hoffman, J.I. Evidence for an Allee Effect in a Declining Fur Seal Population. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2021, 288, rspb.2020.2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, D.J.; Brownell, R.L.; Bonin, C.A.; Woodman, S.M.; Shaftel, D.; Watters, G.M. Evaluating Threats to South Shetland Antarctic Fur Seals amidst Population Collapse. Mamm. Rev. 2024, 54, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulloa, M.; Fernández, A.; Ariyama, N.; Colom-Rivero, A.; Rivera, C.; Nuñez, P.; Sanhueza, P.; Johow, M.; Araya, H.; Torres, J.C.; et al. Mass Mortality Event in South American Sea Lions (Otaria flavescens) Correlated to Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) H5N1 Outbreak in Chile. Vet. Q. 2023, 43, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás, G.; Marandino, A.; Panzera, Y.; Rodríguez, S.; Wallau, G.L.; Dezordi, F.Z.; Pérez, R.; Bassetti, L.; Negro, R.; Williman, J.; et al. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 Virus Infections in Pinnipeds and Seabirds in Uruguay: Implications for Bird-Mammal Transmission in South America. Virus Evol. 2024, 10, veae031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, C.; Uhart, M.; Falabella, V.; Campagna, J.; Zavattieri, V.; Vanstreels, R.E.T.; Lewis, M.N. Catastrophic Mortality of Southern Elephant Seals Caused by H5N1 Avian Influenza. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2024, 40, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elorriaga-Verplancken, F.R.; Sierra-Rodríguez, G.E.; Rosales-Nanduca, H.; Acevedo-Whitehouse, K.; Sandoval-Sierra, J. Impact of the 2015 El Niño-Southern Oscillation on the Abundance and Foraging Habits of Guadalupe Fur Seals and California Sea Lions from the San Benito Archipelago, Mexico. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Vallejo, R.A.; Elorriaga-Verplancken, F.R.; Rosales-Nanduca, H.; Hernández-Camacho, C.J.; Moncayo-Estrada, R.; Gómez-Gutiérrez, J.; González-Armas, R.; Rodríguez-Rafael, E.D.; González-López, I. Abundance, Isotopic Amplitude, and Pups Body Mass of California Sea Lions (Zalophus californianus) from the Southwest Gulf of California during Anomalous Warming Events. Mar. Biol. 2024, 171, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, D.; Thalmann, S.; Wotherspoon, S.; Lea, M.A. Is Regional Variability in Environmental Conditions Driving Differences in the Early Body Condition of Endemic Australian Fur Seal Pups? Wildl. Res. 2023, 50, 993–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, M.A.; Bartés, S.N.; Grandi, M.F.; Brogger, M.; Svendsen, G.; González, R.; Crespo, E.A. Impact of the Avian Influenza Outbreak on the Population Dynamics of South American Sea Lions Otaria byronia in Northern Patagonia. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2025, 41, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.; Robertson, B.C.; Chilvers, B.L.; Krkošek, M. Marine Mammal Population Decline Linked to Obscured By-Catch. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 11781–11786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luck, C.; Jessopp, M.; Cronin, M.; Rogan, E. Using Population Viability Analysis to Examine the Potential Long-Term Impact of Fisheries Bycatch on Protected Species. J. Nat. Conserv. 2022, 67, 126157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, K.M.; Aguilar, A.; Aurioles, D.; Burkanov, V.; Campagna, C.; Gales, N.; Gelatt, T.; Goldsworthy, S.D.; Goodman, S.J.; Hofmeyr, G.J.G.; et al. Global Threats to Pinnipeds. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2012, 28, 414–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, B.C.; Chilvers, B.L. The Population Decline of the New Zealand Sea Lion Phocarctos hookeri: A Review of Possible Causes. Mamm. Rev. 2011, 41, 253–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylis, A.M.M.; Orben, R.A.; Arnould, J.P.Y.; Christiansen, F.; Hays, G.C.; Staniland, I.J. Disentangling the Cause of a Catastrophic Population Decline in a Large Marine Mammal. Ecology 2015, 96, 2834–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydeman, W.J.; Allen, S.G. Pinniped Population Dynamics in Central California: Correlations with Sea Surface Temperature and Upwelling Indices. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 1999, 15, 446–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilvers, B.L. Using Life-history Traits of New Zealand Ealand Sea Lions, Auckland Islands to Clarify Potential Causes of Decline. J. Zool. 2012, 287, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, I.L. Environmental and Physiological Factors Controlling the Reproductive Cycles of Pinnipeds. Can. J. Zool. 1991, 69, 1135–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauplet, G.; Barbraud, C.; Chambellant, M.; Guinet, C. Interannual Variation in the Post-Weaning and Juvenile Survival of Subantarctic Fur Seals: Influence of Pup Sex, Growth Rate and Oceanographic Conditions. J. Anim. Ecol. 2005, 74, 1160–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, R.R.; Kirkman, S.P.; Thalmann, S.; Sutherland, D.R.; Mitchell, A.; Arnould, J.P.Y.; Salton, M.; Slip, D.J.; Dann, P.; Kirkwood, R. Understanding Meta-Population Trends of the Australian Fur Seal, within Sights for Adaptive Monitoring. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinet, C.; Jouventin, P.; Georges, J.-Y. Long Term Population Changes of Fur Seals Arctocephalus gazella and Arctocephalus Tropicalis on Subantarctic (Crozet) and Subtropical (St. Paul and Amsterdam) Islands and Their Possible Relationship to El Niño Southern Oscillation. Antarct. Sci. 1994, 6, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, C.J.A.; Davis, L.S.; Lalas, C.; Harcourt, R.G. Geographic and Temporal Variation in the Condition of Pups of the New Zealand Fur Seal (Arctocephalus forsteri): Evidence for Density Dependence and Differences in the Marine Environment. J. Zool. 2000, 252, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.; Robertson, B.C.; Chilvers, B.L.; Krkošek, M. Population Dynamics Reveal Conservation Priorities of the Threatened New Zealand Sea Lion Phocarctos hookeri. Mar. Biol. 2015, 162, 1587–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, E.R.; Tremblay-Boyer, L.; Berkenbusch, K. Estimated Captures of New Zealand Fur Seal, Common Dolphin, and Turtles in New Zealand Commercial Fisheries, to 2017–18; Ministry for Primary Industries: Wellington, New Zealand, 2021.

- Reif, J.S.; Schaefer, A.M.; Bossart, G.D. Atlantic Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) as a Sentinel for Exposure to Mercury in Humans: Closing the Loop. Vet. Sci. 2015, 2, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, S.J. Use of Surrogates to Predict the Stressor Response of Imperiled Species. Conserv. Biol. 2008, 22, 1564–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grittz, G.S.; Machado, G.M.O.; Vibrans, A.C.; de Gasper, A.L. Commonness as a Reliable Surrogacy Strategy for the Conservation Planning of Rare Tree Species in the Subtropical Atlantic Forest. Biodivers. Conserv. 2024, 33, 1895–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosekov, A.; Kuznetsov, A.; Rada, A.; Ivanova, S. Methods for Monitoring Large Terrestrial Animals in the Wild. Forests 2020, 11, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, K.H.; Nichols, J.D.; Simons, T.R.; Farnsworth, G.L.; Bailey, L.L.; Sauer, J.R. Large Scale Wildlife Monitoring Studies: Statistical Methods for Design and Analysis. Environmetrics 2002, 13, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, K.S. Remote Sensing Change Detection for Ecological Monitoring in United States Protected Areas. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 182, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.A.; Chilvers, B.L.; Weir, J.S. Towards an Abundance Estimate for New Zealand Fur Seal in New Zealand. Aquat. Conserv. 2025, 35, e70142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkson, J.M.; DeMaster, D.P. Use of Pup Counts in Indexing Population Changes in Pinnipeds. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1985, 42, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boren, L.J.; Muller, C.G.; Gemmell, N.J. Colony Growth and Pup Condition of the New Zealand Fur Seal (Arctocephalus forsteri) on the Kaikoura Coastline Compared with Other East Coast Colonies. Wildl. Res. 2006, 33, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilvers, B.L. Pup Numbers, Estimated Population Size, and Monitoring of New Zealand Fur Seals in Doubtful/Pateā, Dusky and Breaksea Sounds, and Chalky Inlet, Fiordland, New Zealand 2021. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2021, 57, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geeson, J.J.; Hobday, A.J.; Speakman, C.N.; Arnould, J.P.Y. Environmental Influences on Breeding Biology and Pup Production in Australian Fur Seals. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2022, 9, 211399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, M.-A.; Guinet, C.; Yves, C.; Duhamel, G.; Dubroca, L.; Pruvost, P.; Hindell, M. Impacts of Climatic Anomalies on Provisioning of a Southern Ocean Predator. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2006, 310, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinet, C.; Roux, J.P.; Bonnet, M.; Mison, V. Effect of Body Size, Body Mass, and Body Condition on Reproduction of Female South African Fur Seals (Arctocephalus Pusillus) in Namibia. Can. J. Zool. 1998, 76, 1418–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandi, M.F.; Sosa Drouville, A.; Fiorito, C.D. Reproductive Alterations in South American Sea Lion during the Avian Influenza H5N1 Outbreak in Northern Patagonia. Acta Biol. Colomb. 2025, 30, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunn, N.J.; Boyd, I.L.; Barton, T.; Croxall, J.P. Factors Affecting the Growth Rate and Mass at Weaning of Antarctic Fur Seals at Bird Island, South Georgia. J. Mammal. 1993, 74, 908–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunn, N.J.; Boyd, I.L.; Croxall, J.P. Reproductive Performance of Female Antarctic Fur Seals: The Influence of Age, Breeding Experience, Environmental Variation and Individual Quality. J. Anim. Ecol. 1994, 63, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speakman, C.N.; Hoskins, A.J.; Hindell, M.A.; Costa, D.P.; Hartog, J.R.; Hobday, A.J.; Arnould, J.P.Y. Environmental Influences on Foraging Effort, Success and Efficiency in Female Australian Fur Seals. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, S.L.; Don Bowen, W.; Boness, D.J.; Iverson, S.J. Maternal Effects on Offspring Mass and Stage of Development at Birth in the Harbor Seal, Phoca vitulina. J. Mammal. 2000, 81, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, J.P.; Zinn, S.A. Extraordinary Diversity of the Pinniped Lactation Triad: Lactation and Growth Strategies of Seals, Sea Lions, Fur Seals, and Walruses. Anim. Front. 2023, 13, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay, S.A.; Fulham, M.; Caraguel, C.G.B.; Gray, R. Mitigating Disease Risk in an Endangered Pinniped: Early Hookworm Elimination Optimizes the Growth and Health of Australian Sea Lion Pups. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1161185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, P.M.; Hall, A.J.; Goodman, S.J.; Cruz, M.; Acevedo-Whitehouse, K. Immune Activity, Body Condition and Human-Associated Environmental Impacts in a Wild Marine Mammal. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.J.; McConnell, B.J.; Barker, R.J. Factors Affecting First-Year Survival in Grey Seals and Their Implications for Life History Strategy. J. Anim. Ecol. 2001, 70, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.; Neale, D. Census & Individual Size of New Zealand Fur Seal/Kekeno Pups on the West Coast South Island from 1991 to 2016; Prepared for Department of Conservation. NIWA Client Report 2016005WN; National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research Ltd.: Wellington, New Zealand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shaughnessy, P.D.; Gales, N.J.; Dennis, T.E.; Goldsworthy, S.D. Distribution and Abundance of New Zealand Fur Seals, Arctocephalus forsteri, in South Australia and Western Australia. Wildl. Res. 1994, 21, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.A.; Chilvers, B.L.; Weir, J.S.; Boren, L.J. Earthquake Impacts on a Protected Pinniped in New Zealand. Aquat. Conserv. 2024, 34, e4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.A.; Chilvers, B.L.; Weir, J.S. Planning for a Pinniped Response during a Marine Oil Spill. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 10929–10944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, D.G. Inverse, Multiple and Sequential Sample Censuses. Biometrics 1952, 8, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gales, N.J.; Fletcher, D.J. Abundance, Distribution and Status of the New Zealand Sea Lion, Phocarctos hookeri. Wildl. Res. 1999, 26, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitcher, K.W. Variation in Blubber Thickness of Harbor Seals in Southern Alaska. J. Wildl. Manag. 1986, 50, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fewster, R.M.; Buckland, S.T.; Siriwardena, G.M.; Baillie, S.R.; Wilson, J.D. Analysis of Population Trends for Farmland Birds Using Generalized Additive Models. Ecology 2000, 81, 1970–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781498728348. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Simpson, G.L. Modelling Palaeoecological Time Series Using Generalised Additive Models. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, G.L. gratia: An R package for exploring generalized additive models. J. Open Source Softw. 2024, 9, 6962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoń, K. Package “MuMIn” Multi-Model Inference. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/MuMIn/MuMIn.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Watson, D.M.; Beaven, B.; Bradshaw, C.J.A. Population Trends of New Zealand Fur Seals in the Rakiura Region Based on Long-Term Population Surveys and Traditional Ecological Knowledge. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2015, 49, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDiarmid, A.; Lalas, C. Rapid Recolonisation of South-Eastern New Zealand by New Zealand Fur Seals Arctocephalus forsteri; Unpublished Final Research Report prepared for the Ministry of Fisheries project ZBD2005-5 MS12 Part E; Ministry of Fisheries: Wellington, New Zealand, 2014; 17p.

- Bradshaw, C.J.A.; Harcourt, R.G.; Davis, L.S. Male-Biased Sex Ratios in New Zealand Fur Seal Pups Relative to Environmental Variation. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2003, 53, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilvers, B.L.; Wilson, K.J.; Hickling, G.J. Suckling Behaviours and Growth Rates of New Zealand Fur Seals, Arctocephalus forsteri, at Cape Foulwind, New Zealand. N. Z. J. Zool. 1995, 22, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, C.; Condit, R.; Ferrari, M.; Campagna, J.; Eder, E.; Uhart, M.; Vanstreels, R.E.T.; Falabella, V.; Lewis, M.N. Predicting Population Consequences of an Epidemic of High Pathogenicity Avian Influenza on Southern Elephant Seals. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2025, 41, e70009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, K.H.; Trites, A.W.; Arias-Schreiber, M. The Effects of Prey Availability on Pup Mortality and the Timing of Birth of South American Sea Lions (Otaria flavescens) in Peru. J. Zool. 2004, 264, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, I.L. Pup Production and Distribution of Breeding Antarctic Fur Seals (Arctocephalus gazella) at South Georgia. Antarct. Sci. 1993, 5, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, R.R.; Sorrell, K.J.; Thalmann, S.; Mitchell, A.; Gray, R.; Schinagl, H.; Arnould, J.P.Y.; Dann, P.; Kirkwood, R. Sustained Reduction in Numbers of Australian Fur Seal Pups: Implications for Future Population Monitoring. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, E.S.; Chilvers, B.L.; Nakagawa, S.; Moore, A.B.; Robertson, B.C. Sexual Segregation in Juvenile New Zealand Sea Lion Foraging Ranges: Implications for Intraspecific Competition, Population Dynamics and Conservation. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mckenzie, J.; Parry, L.J.; Page, B.; Goldsworthy, S.D. Estimation of Pregnancy Rates and Reproductive Failure in New Zealand Fur Seals (Arctocephalus forsteri). J. Mammal. 2005, 86, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbens, J.; Parry, L.J.; Arnould, J.P.Y. Influences on Fecundity in Australian Fur Seals (Arctocephalus Pusillus Doriferus). J. Mammal. 2010, 91, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florko, K.R.N.; Tai, T.C.; Cheung, W.W.L.; Ferguson, S.H.; Sumaila, U.R.; Yurkowski, D.J.; Auger-Méthé, M. Predicting How Climate Change Threatens the Prey Base of Arctic Marine Predators. Ecol. Lett. 2021, 24, 2563–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, T.; Ansorge, I.; Bornemann, H.; Plötz, J.; Tosh, C.; Bester, M. Elephant Seal Dive Behaviour Is Influenced by Ocean Temperature: Implications for Climate Change Impacts on an Ocean Predator. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2011, 441, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Ruiz, A.; Pardo, M.A.; Hernández-Montoya, J.C.; Elorriaga-Verplancken, F.R.; MilanÉs-Salinas, M.D.L.Á.; Norris, T.; Beier, E.; Heckel, G. Guadalupe Fur Seal Pup Production Predicted from Annual Variations of Sea Surface Temperature in the Southern California Current Ecosystem. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2022, 79, 1637–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.O.; Escobar-Flores, P.C.; Datta, S.; Edwards, C.T.T.; O’Driscoll, R.L. Climate Effects on Key Fish and Megafauna Species of the New Zealand Subantarctic Zone and Adjacent Regions of High Productivity; New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No. 300; Fisheries New Zealand Tini a Tangaroa: Wellington, New Zealand, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Salinger, M.J.; Trenberth, K.E.; Diamond, H.J.; Behrens, E.; Fitzharris, B.B.; Herold, N.; Smith, R.O.; Sutton, P.J.; Trought, M.C.T. Climate Extremes in the New Zealand Region: Mechanisms, Impacts and Attribution. Int. J. Climatol. 2024, 44, 5809–5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puryear, W.; Sawatzki, K.; Hill, N.; Foss, A.; Stone, J.J.; Doughty, L.; Walk, D.; Gilbert, K.; Murray, M.; Cox, E.; et al. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus Outbreak in New England Seals, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leguia, M.; Garcia-Glaessner, A.; Muñoz-Saavedra, B.; Juarez, D.; Barrera, P.; Calvo-Mac, C.; Jara, J.; Silva, W.; Ploog, K.; Amaro, L.; et al. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A (H5N1) in Marine Mammals and Seabirds in Peru. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.; Gias, E.; Little, A.; Jauregui, R.; Low, Y.S.; Pulford, D.; Steyn, A.; Sylvester, K.; Green, D.; O’Keefe, J.; et al. Genome Sequence of a Divergent Strain of Canine Distemper Virus Detected in New Zealand Fur Seals. Genome Announc. 2025, 14, e0015125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J.; Doonan, I. Quantitative Risk Assessment of Threats to New Zealand Sea Lions; New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No. 166; Ministry for Primary Industries, Manatū Ahu Matua: Wellington, New Zealand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chilvers, B.L.; Wilkinson, I.S.; Childerhouse, S. New Zealand Sea Lion, Phocarctos hookeri, Pup Production—1995 to 2006. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2007, 41, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härkönen, T.; Dietz, R.; Reijnders, P.; Teilmann, J.; Harding, K.; Hall, A.; Brasseur, S.; Siebert, U.; Goodman, S.J.; Jepson, P.D.; et al. A review of the 1988 and 2002 phocine distemper virus epidemics in European harbour seals. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2006, 68, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkman, S.P.; Lavigne, D.M. Assessing the Hunting Practices of Namibia’s Commercial Seal Hunt. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2010, 106, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami-Khoyi, A.; Paterson, A.M.; Hartley, D.A.; Boren, L.J.; Cruickshank, R.H.; Ross, J.G.; Murphy, E.C.; Else, T.A. Mitogenomics Data Reveal Effective Population Size, Historical Bottlenecks, and the Effects of Hunting on New Zealand Fur Seals (Arctocephalus forsteri). Mitochondrial DNA A DNA Mapp. Seq. Anal. 2018, 29, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuff. Department of Conservation Police Have “solid Lead” in Kaikōura Seal Killing Case—DOC. Available online: https://www.stuff.co.nz/environment/300658609/police-have-solid-lead-in-kaikura-seal-killing-case--doc (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Goldsworthy, S.D.; Page, B. A Risk-Assessment Approach to Evaluating the Significance of Seal Bycatch in Two Australian Fisheries. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 139, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsworthy, S.D.; Page, B.; Hamer, D.J.; Lowther, A.D.; Shaughnessy, P.D.; Hindell, M.A.; Burch, P.; Costa, D.P.; Fowler, S.L.; Peters, K.; et al. Assessment of Australian Sea Lion Bycatch Mortality in a Gillnet Fishery, and Implementation and Evaluation of an Effective Mitigation Strategy. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 799102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavanato, H.; Schattschneider, J.; Childerhouse, S.; Briscoe, D. Assessment of New Zealand Fur Seal/Kekeno Bycatch by Trawlers in the Cook Strait Hoki Fishery; Prepared for Department of Conservation. Cawthron Report No. 3854; Cawthron Institute: Nelson, New Zealand, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, R.R.; Kirkwood, R.; Sutherland, D.R.; Dann, P. Drivers and Annual Estimates of Marine Wildlife Entanglement Rates: A Long-Term Case Study with Australian Fur Seals. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 101, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.A.; Chilvers, B.L.; Weir, J.S.; Vidulich, A.; Godfrey, A.J.R. Post-Earthquake Highway Reconstruction: Impacts and Mitigation Opportunities for New Zealand Pinniped Population. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2023, 245, 106851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mearns, A.J.; Levine, E.; Ender, R.Y.; Helton, D.; Loughlin, T. Protecting Fur Seals during Spill Response: Lessons from the San Jorge (Uruguay) Oil Spill. In Proceedings of the International Oil Spill Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 7–12 March 1999; American Petroleum Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; pp. 467–470. [Google Scholar]

- Mattlin, R.H. Pup Mortality of the New Zealand Fur Seal (Arctocephalus forsteri Lesson). N. Z. J. Ecol. 1978, 1, 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Chilvers, B.L.; Robertson, B.C.; Wilkinson, I.S.; Duignan, P.J.; Gemmell, N.J. Male Harassment of Female New Zealand Sea Lions, Phocarctos Hookeri: Mortality, Injury, and Harassment Avoidance. Can. J. Zool. 2005, 83, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, Z.; Stobo, W.T. Shark-inflicted Mortality on a Population of Harbour Seals (Phoca vitulina) at Sable Island, Nova Scotia. J. Zool. 2000, 252, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, R.R.; de Bruyn, P.J.N.; Bester, M.N. Predatory Impact of Killer Whales on Pinniped and Penguin Populations at the Subantarctic Prince Edward Islands: Fact and Fiction. J. Zool. 2011, 285, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, J.-P. The Impact of Environmental Variability on the Seal Population. Namib. Brief. 1988, 20, 138–140. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, K.; Forcada, J. Causes of Offspring Mortality in the Antarctic Fur Seal, Arctocephalus gazella: The Interaction of Density Dependence and Ecosystem Variability. Can. J. Zool. 2005, 83, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, D.I.; Fletcher, D.J.; Dillingham, P.W.; Meyer, S.; Pavanato, H. Updated Spatially Explicit Fisheries Risk Assessment for New Zealand Marine Mammal Populations; Fisheries New Zealand, Ministry for Primary Industries: Wellington, New Zealand, 2022; ISBN 9781991052261. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, E.R.; Berkenbusch, K. Estimated Captures of New Zealand Fur Seal, New Zealand Sea Lion, Common Dolphin, and Turtles in New Zealand Commercial Fisheries, 1995–96 to 2014–15; Ministry for Primary Industries, Manatū Ahu Matua: Wellington, New Zealand, 2017.

- Ministry for Primary Industries. Marine Mammals Overview. Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Annual Review (AEBAR); Ministry for Primary Industries: Wellington, New Zealand, 2025.

- Chilvers, B.L.; Wilkinson, I.S.; Mackenzie, D.I. Predicting Life-History Traits for Female New Zealand Sea Lions, Phocarctos hookeri: Integrating Short-Term Mark-Recapture Data and Population Modeling. J. Agric. Biol. Env. Stat. 2010, 15, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistorius, P.A.; Bester, M.N.; Lewis, M.N.; Taylor, F.E.; Campagna, C.; Kirkman, S.P. Adult Female Survival, Population Trend, and the Implications of Early Primiparity in a Capital Breeder, the Southern Elephant Seal (Mirounga Leonina). J. Zool. 2004, 263, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, J.R.; Caswell, H.; Derocher, A.E.; Lewis, M.A. Ringed Seal Demography in a Changing Climate. Ecol. Appl. 2019, 29, e01855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harcourt, R.G. Advances in New Zealand Mammalogy 1990–2000: Pinnipeds. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 2001, 31, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, B.; Hindell, M.; Bester, M.; Trathan, P.; Jonsen, I.; Staniland, I.; Oosthuizen, W.C.; Wege, M.; Lea, M.A. Return Customers: Foraging Site Fidelity and the Effect of Environmental Variability in Wide-Ranging Antarctic Fur Seals. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, C.; Pardo, M.A.; Elorriaga-Verplancken, F.R. Impacts of Extreme Ocean Warming on the Early Development of a Marine Top Predator: The Guadalupe Fur Seal. Prog. Ocean. 2020, 180, 102220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanniard-Du-dot, T.; Trites, A.W.; Arnould, J.P.Y.; Guinet, C. Reproductive Success Is Energetically Linked to Foraging Efficiency in Antarctic Fur Seals. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, S.P.; Costa, D.P.; Harrison, A.-L.; Kotze, P.G.H.; Oosthuizen, W.H.; Weise, M.; Botha, J.A.; Arnould, J.P.Y. Dive Behaviour and Foraging Effort of Female Cape Fur Seals Arctocephalus pusillus pusillus. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019, 6, 191369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, D.; McMahon, C.; Hindell, M.; Goldsworthy, S.; Bailleul, F. Influence of Shelf Oceanographic Variability on Alternate Foraging Strategies in Long-Nosed Fur Seals. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2019, 615, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliska, K.; Mcintosh, R.R.; Jonsen, I.; Hume, F.; Dann, P.; Kirkwood, R.; Harcourt, R. Environmental Correlates of Temporal Variation in the Prey Species of Australian Fur Seals Inferred from Scat Analysis. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2022, 9, 211723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalas, C.; Webster, T. Contrast in the Importance of Arrow Squid as Prey of Male New Zealand Sea Lions and New Zealand Fur Seals at The Snares, Subantarctic New Zealand. Mar. Biol. 2014, 161, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, D.; Chilvers, B.L. Establishment of a Stable Isotope Database for New Zealand Fur Seal Breeding Colonies Using Δ13C and Δ15N in Pup Vibrissae. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2025, 59, 1164–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B.; Jensz, K.; Cawthorn, M.; Cunningham, R. Census of New Zealand Fur Seals on the West Coast of New Zealand’s South Island. Report Prepared for Deepwater Group Limited; Latitude 42 Consultants: Kettering, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bas, M.; Ouled-Cheikh, J.; Fuster-Alonso, A.; Julià, L.; March, D.; Ramírez, F.; Cardona, L.; Coll, M. Potential Spatial Mismatches Between Marine Predators and Their Prey in the Southern Hemisphere in Response to Climate Change. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2025, 31, e70080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baily, J.L.; Foster, G.; Brown, D.; Davison, N.J.; Coia, J.E.; Watson, E.; Pizzi, R.; Willoughby, K.; Hall, A.J.; Dagleish, M.P. Salmonella Infection in Grey Seals (Halichoerus grypus), a Marine Mammal Sentinel Species: Pathogenicity and Molecular Typing of Salmonella Strains Compared with Human and Livestock Isolates. Env. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran, R.S.; Payne, A.R.; Marm Kilpatrick, A.; Hale, C.M.; Reed, M.; Hazen, E.L.; Bograd, S.J.; Jouma, J.; Robinson, P.W.; Houle, E.; et al. Elephant Seals as Ecosystem Sentinels for the Northeast Pacific Ocean Twilight Zone. Science 2025, 387, 764–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Colony | Year | Dates of Marking | No. Pups Marked | Dates of Recapture | Mean Mark-Recapture Estimate (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wekakura Point | 2018 | 30–31 January | 150 | 31 January–2 February, 27 February | 248 (230–265) |

| 2020 | 27–28 January | 106 | 29–30 January | 254 (231–278) | |

| 2023 | 24–26 January | 93 | 25–27 January | 143 (133–152) | |

| 2025 | 28–29 January | 135 | 29–31 January | 186 (178–194) | |

| Cape Foulwind | 2018 | 30–31 January | 118 | 7–9 February | 149 (139–160) |

| 2020 | 28–29 January | 129 | 30 January–31 January, 11 February | 177 (154–200) | |

| 2023 | 26–27 January | 60 | 1–3 February | 93 (81–104) | |

| 2025 | 28–30 January | 89 | 31 January–2 February | 131 (122–140) | |

| Taumaka Island | 2018 | 4–5 February | 350 | 6–7 February | 916 (910–922) |

| 2020 | 27–30 January | 384 | 31 January–1 February | 989 (888–1089) | |

| 2023 | 22–25 January | 368 | 26–27 January | 638 (619–657) | |

| 2025 | 27–29 January | 357 | 30–31 January | 566 (555–577) |

| Colony | Adjusted R2 | Deviance Explained | Smooth Year Term Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wekakura Point | 0.883 | 93.8% | edf = 7.21, F = 41.59, p < 0.001 |

| Cape Foulwind | 0.853 | 89.6% | edf = 8.18, F = 18.68, p < 0.001 |

| Taumaka Island | 0.669 | 75.9% | edf = 7.63, F = 6.89, p < 0.001 |

| Colony | Period | Percentage Change (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Wekakura Point | 1996–2016 | −78.7 |

| 2016–2025 | −20.5 | |

| Cape Foulwind | 1993–2016 | −67.9 |

| 2016–2025 | −8.4 | |

| Taumaka Island | 1995–2016 | −36 |

| 2016–2025 | −38.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hall, A.A.; Neale, D.; Roberts, J.; Chilvers, B.L.; Weir, J.S. Declining Abundance and Variable Condition of Fur Seal (Arctocephalus forsteri) Pups on the West Coast of New Zealand’s South Island. Animals 2026, 16, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010121

Hall AA, Neale D, Roberts J, Chilvers BL, Weir JS. Declining Abundance and Variable Condition of Fur Seal (Arctocephalus forsteri) Pups on the West Coast of New Zealand’s South Island. Animals. 2026; 16(1):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010121

Chicago/Turabian StyleHall, Alasdair A., Don Neale, Jim Roberts, B. Louise Chilvers, and Jody Suzanne Weir. 2026. "Declining Abundance and Variable Condition of Fur Seal (Arctocephalus forsteri) Pups on the West Coast of New Zealand’s South Island" Animals 16, no. 1: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010121

APA StyleHall, A. A., Neale, D., Roberts, J., Chilvers, B. L., & Weir, J. S. (2026). Declining Abundance and Variable Condition of Fur Seal (Arctocephalus forsteri) Pups on the West Coast of New Zealand’s South Island. Animals, 16(1), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010121