A Comparison of Two Different Methods for Inducing Apnoea During Thoracic Computed Tomography of Dogs

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Animals

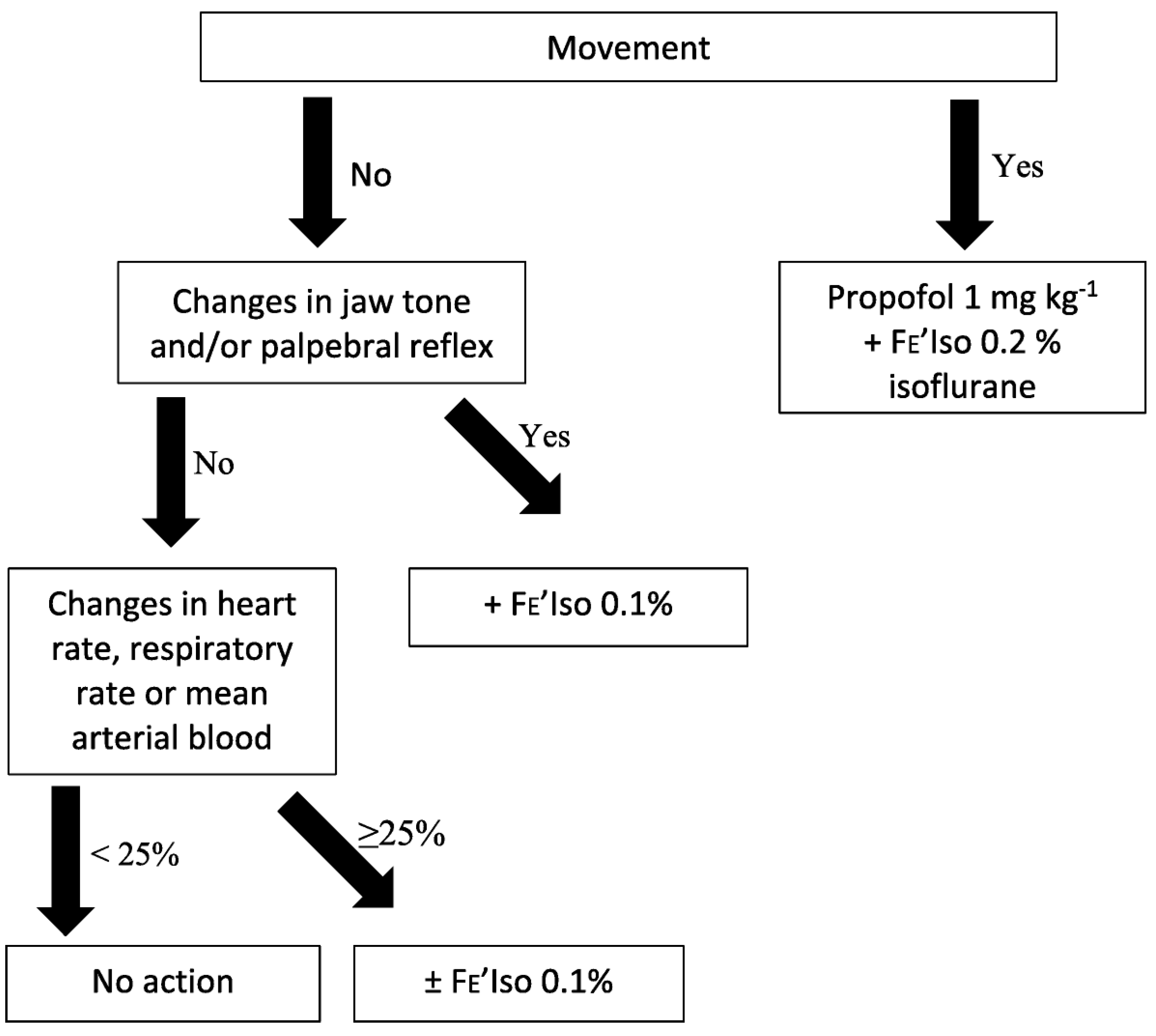

2.3. General Anaesthesia Protocol

- Firstly, a 5 mL kg−1 bolus of Hartmann’s solution was administered over 5 min or at a maximum rate of 1200 mL h−1. This was repeated if the patient was fluid-responsive but the duration of effect was only transient.

- Ephedrine 0.1 mg kg−1 was administered IV if the patient was not fluid-responsive. This was repeated if it was effective but the duration of effect was only transient.

- A dopamine CRI was administered at an initial rate of 5 μg kg−1 min−1 if the patient was refractory to ephedrine. The CRI was increased incrementally to a maximum of 15 μg kg−1 min−1 if required.

- Treatment as per the anaesthetist’s discretion was initiated if the patient was refractory to dopamine and the primary investigator was informed.

2.4. Study Protocol

- Hypoxaemia caused by apnoea, defined as a SpO2 of less than 90%, as determined by pulse oximetry. Artificial IPPV was initiated until SpO2 reached 95%.

- An ETCO2 of 70 mmHg or more. Artificial IPPV was initiated to target an ETCO2 of 60 mmHg or less.

- Apnoea lasting more than 120 s. Artificial IPPV was initiated.

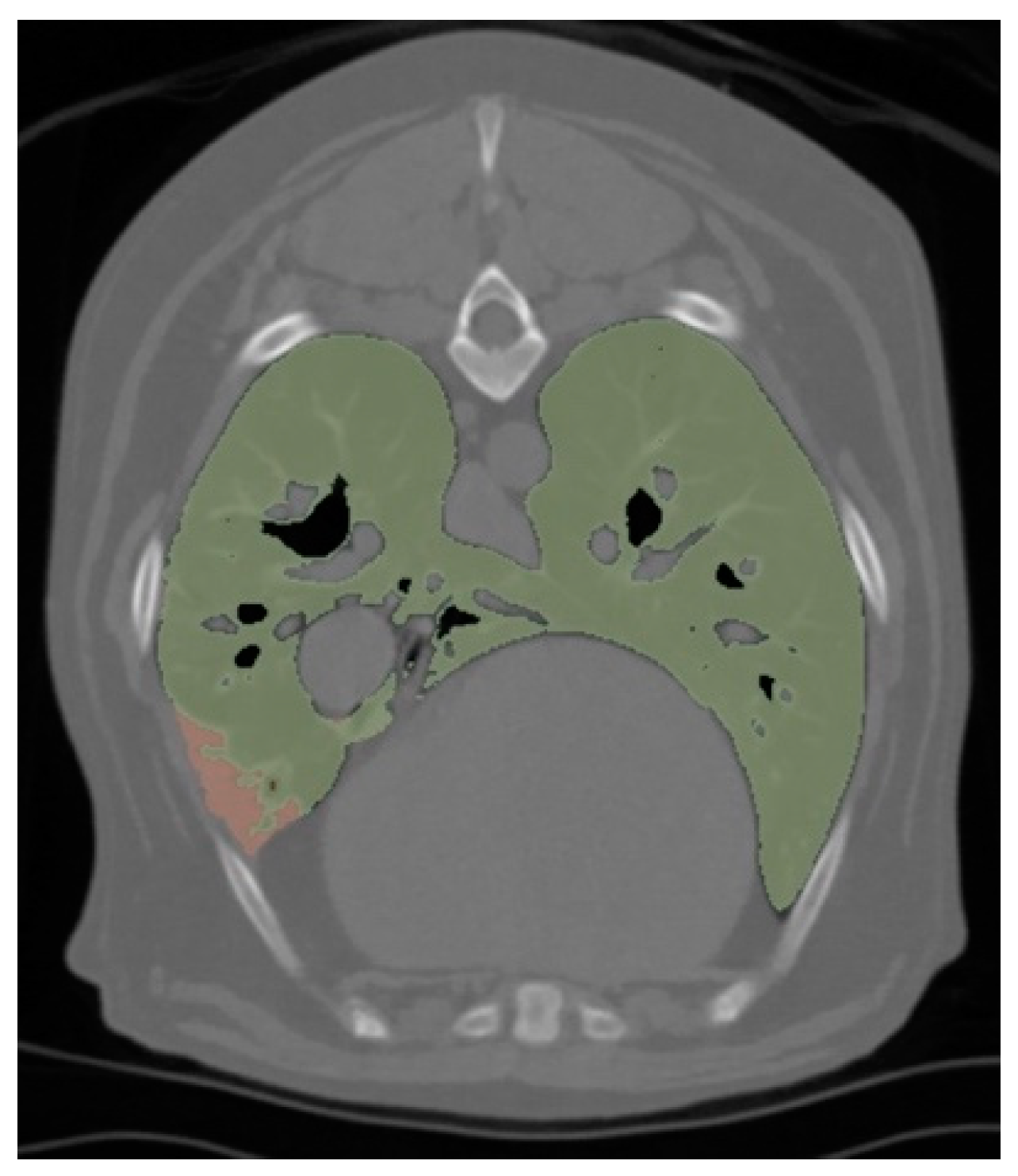

2.5. Radiological Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. General Anaesthesia Protocol

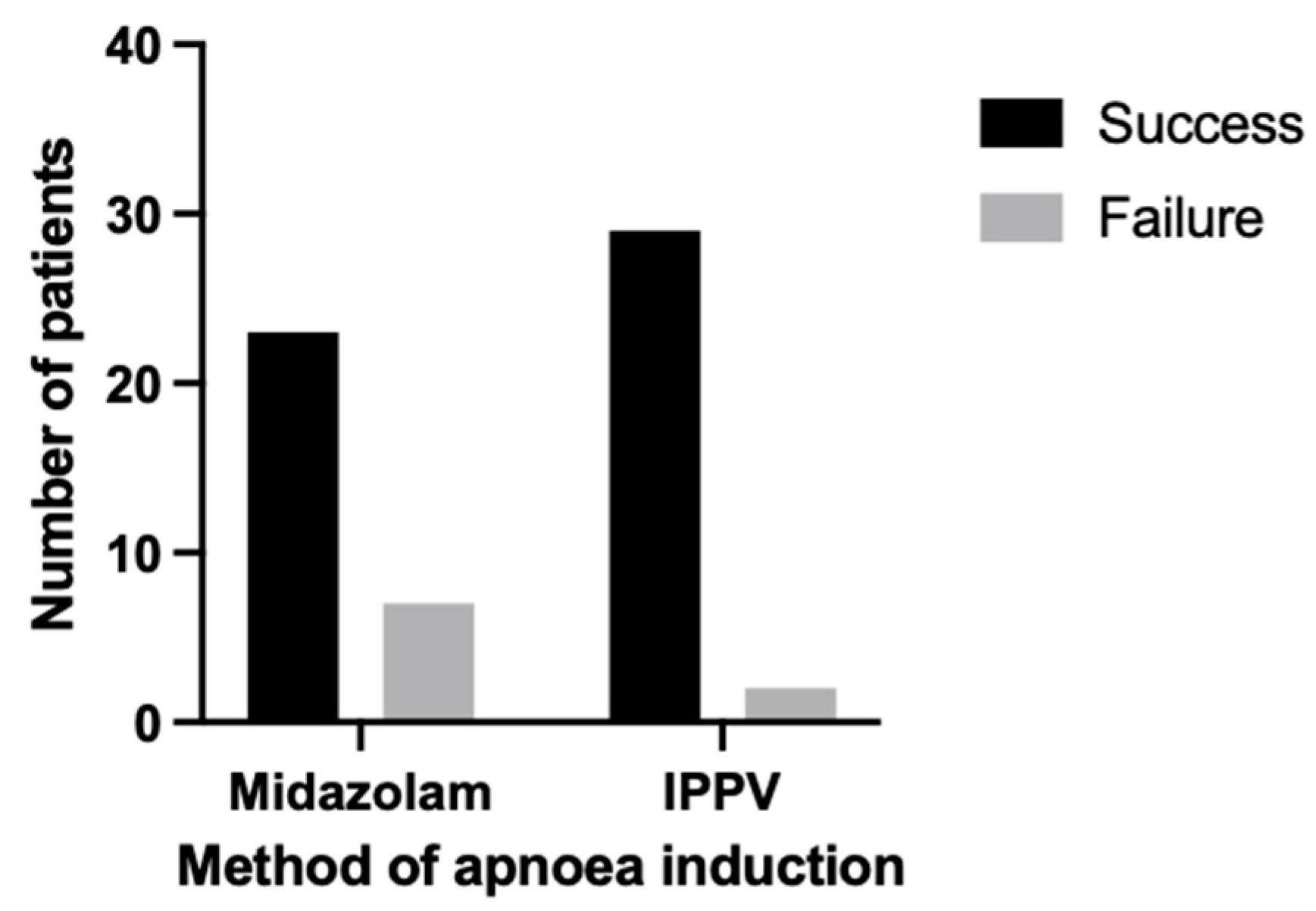

3.3. Apnoea

3.4. Cardiorespiratory Parameters and Complications

3.5. Radiological Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guarracino, A.; Lacitignola, L.; Auriemma, E.; De Monte, V.; Grasso, S.; Crovace, A.; Staffieri, F. Which Airway Pressure Should Be Applied During Breath-Hold in Dogs Undergoing Thoracic Computed Tomography? Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2016, 57, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henao-Guerrero, N.; Ricco, C.; Jones, J.C.; Buechner-Maxwell, V.; Daniel, G.B. Comparison of four ventilatory protocols for computed tomography of the thorax in healthy cats. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2012, 73, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choen, S.; McLarty, E.M.; Pascoe, P.; Zwingenberger, A.L. Positive-pressure breath-hold positron emission tomography/computed tomography is feasible for respiratory-induced artifact reduction in healthy dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2022, 83, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keates, H.; Whittem, T. Effect of intravenous dose escalation with alfaxalone and propofol on occurrence of apnoea in the dog. Res. Vet. Sci. 2012, 93, 904–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.; Hughes, E.; Gurney, M. Co-induction of anaesthesia with alfaxalone and midazolam in dogs: A randomized, blinded clinical trial. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2019, 46, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegmann, G.F.; Bester, L. Some cardiopulmonary effects of midazolam premedication in clenbuterol-treated bitches during surgical endoscopic examination of the uterus and ovariohysterectomy. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 2001, 72, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heniff, M.S.; Moore, G.P.; Trout, A.; Cordell, W.H.; Nelson, D.R. Comparison of routes of flumazenil administration to reverse midazolam-induced respiratory depression in a canine model. Acad. Emerg. Med. 1997, 4, 1115–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, L.P. Sedatives and Tranquilizers. In Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 10th ed.; Riviere, J.E., Papich, M.G., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 324–368. ISBN 9781118855775. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.J.; Stehling, L.C.; Zauder, H.L. Cardiovascular responses to diazepam and midazolam maleate in the dog. Anesthesiology 1979, 51, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schläppi, B. Safety aspects of midazolam. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1983, 16 (Suppl. S1), 37s–41s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugdale, A. Small animal sedation and premedication. In Veterinary Anaesthesia: Principles to Practice, 1st ed.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2010; p. 35. ISBN 978-1-4051-9247-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez Castro, L.N.; Mehta, J.H.; Brayanov, J.B.; Mullen, G.J. Quantification of respiratory depression during pre-operative administration of midazolam using a non-invasive respiratory volume monitor. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, A.; Gardaz, J.P.; Suter, P.M.; Gemperle, M. Respiratory depression by midazolam and diazepam. Anesthesiology 1980, 53, 494–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kropf, J.; Hughes, J.M.L. Effects of midazolam on cardiovascular responses and isoflurane requirement during elective ovariohysterectomy in dogs. Ir. Vet. J. 2018, 71, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Electronic Medicines Compendium. Hypnovel 10 mg in 2 mL. Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/10948/smpc#gref (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- White, J.M.; Irvine, R.J. Mechanisms of fatal opioid overdose. Addiction 1999, 94, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italiano, M.; Robinson, R. Effect of benzodiazepines on the dose of alfaxalone needed for endotracheal intubation in healthy dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2018, 45, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, K.A.; Robertson, S.A.; Wilson, D.V. Alfaxalone alone or combined with midazolam or ketamine in dogs: Intubation dose and select physiologic effects. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2017, 44, 766–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, A.; Laredo, F.G.; Escobar, M.; Agut, A.; Soler, M.; Belda, E. Effects of midazolam before or after alfaxalone for co-induction of anaesthesia in healthy dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2018, 45, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covey-Crump, G.L.; Murison, P.J. Fentanyl or midazolam for co-induction of anaesthesia with propofol in dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2008, 35, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, A.; Giuffrida, M.; Larenza, M.P. Midazolam, as a co-induction agent, has propofol sparing effects but also decreases systolic blood pressure in healthy dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2014, 41, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, K.; Lehnus, K.; Liu, N.C.; Bigby, S.E. Determining an optimum propofol infusion rate for induction of anaesthesia in healthy dogs: A randomized clinical trial. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2022, 49, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prather, A.B.; Berry, C.R.; Thrall, D.E. Use of radiography in combination with computed tomography for the assessment of noncardiac thoracic disease in the dog and cat. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2005, 46, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandi, F.; Mattoon, J.S.; Lakritz, J.; Turk, J.R.; Wisner, E.R. Correlation of helical and incremental high-resolution thin-section computed tomographic imaging with histomorphometric quantitative evaluation of lungs in dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2003, 64, 935–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennler, M.; Bass, D.A.; Gutierrez-Crespo, B.; Schnyder, M.; Guscetti, F.; Di Cesare, A.; Deplazes, P.; Kircher, P.R.; Glaus, T.M. Thoracic computed tomography, angiographic computed tomography, and pathology findings in six cats experimentally infected with Aelurostrongylus abstrusus. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2013, 54, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonell, W.N.; Kerr, C.L. Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Anesthetic Management of Patients with Respiratory Disease. In Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia: The Fifth Edition of Lumb and Jones, 5th ed.; Grimm, K.A., Lamont, L.A., Tranquilli, W.J., Greene, S.A., Robertson, S.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Chichester, UK, 2015; pp. 513–555. ISBN 978-1-118-52623-1. [Google Scholar]

- Staffieri, F.; Franchini, D.; Carella, G.L.; Montanaro, M.G.; Valentini, V.; Driessen, B.; Grasso, S.; Crovace, A. Computed tomographic analysis of the effects of two inspired oxygen concentrations on pulmonary aeration in anesthetized and mechanically ventilated dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2007, 68, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, C.R.; Henzler, M.A.; Johnson, R.A.; Drees, R. Assessment of respiration-induced displacement of canine abdominal organs in dorsal and ventral recumbency using multislice computed tomography. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2015, 56, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Monte, V.; Grasso, S.; De Marzo, C.; Crovace, A.; Staffieri, F. Effects of reduction of inspired oxygen fraction or application of positive end-expiratory pressure after an alveolar recruitment maneuver on respiratory mechanics, gas exchange, and lung aeration in dogs during anesthesia and neuromuscular blockade. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2013, 74, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bignell, B. Computed tomography acquisition for veterinary diagnostic imaging. Vet. Nurse 2022, 13, 378–382. [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson, L.; Spahn, D.R. New concepts of atelectasis during general anaesthesia. Br. J. Anaesth. 2003, 91, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASA PHYSICAL STATUS CLASSIFICATION. Available online: https://www.thinkanaesthesia.com.au/sites/default/files/2024-05/ASA%20Physical%20Status%20Classification%20Chart%20%26%20Premedication%20Chart%20Digital.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Veen, I.; de Grauw, J.C. Methods Used for Endotracheal Tube Cuff Inflation and Pressure Verification in Veterinary Medicine: A Questionnaire on Current Practice. Animals 2022, 12, 3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffato, M.; Novello, L.; Clark, L. What is the definition of intraoperative hypotension in dogs? Results from a survey of diplomates of the ACVAA and ECVAA. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2015, 42, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, R.; Murison, P.J. Automatic ventilators. In BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 3rd ed.; Duke-Novakovski, T., de Vries, M., Seymour, C., Eds.; British Small Animal Veterinary Association: Gloucester, UK, 2016; pp. 65–76. ISBN 978-1-910443-23-1. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, A.G.; Sullivan, K.M.; Soe, M.; Pezzullo, J.C.; Mir, R.A. Sample Size:X-Sectional, Cohort, & Randomised Clinical Trials. Available online: https://www.openepi.com/SampleSize/SSCohort.htm (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- Midazolam Injection Hospira: Package Insert/Prescribing Info. Available online: https://www.drugs.com/pro/midazolam-injection-hospira.html (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Glisson, S.N. Investigation of midazolam’s influence on physiological and hormonal responses to hypotension. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1987, 9, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman, S.; Reves, J.G.; Harris, D. Circulatory responses to midazolam anesthesia: Emphasis on canine splanchnic circulation. Anesth. Analg. 1983, 62, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adams, P.; Gelman, S.; Reves, J.G.; Greenblatt, D.J.; Alvis, J.M.; Bradley, E. Midazolam pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics during acute hypovolemia. Anesthesiology 1985, 63, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, W.; O’Brien, R.; Scrivani, P. The lung parenchyma. In BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Thoracic Imaging; Schwarz, T., Johnson, V., Eds.; British Small Animal Veterinary Association: Gloucester, UK, 2008; pp. 283–286. ISBN 978-0-905214-97-9. [Google Scholar]

- Reimegård, E.; Lee, H.T.N.; Westgren, F. Prevalence of lung atelectasis in sedated dogs examined with computed tomography. Acta Vet. Scand. 2022, 64, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, T.D.; Wallack, S.T. Minimal atelectasis and poorly aerated lung on thoracic CT images of normal dogs acquired under sedation. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2021, 62, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grint, N.J.; Burford, J.; Dugdale, A.H. Does pethidine affect the cardiovascular and sedative effects of dexmedetomidine in dogs? J. Small Anim. Pract. 2009, 50, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.C.; Hecker, K.G.; Pang, D.S.J. Sedation levels in dogs: A validation study. BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 13, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugdale, A. Small animal sedation and premedication, Injectable anaesthetic agents. In Veterinary Anaesthesia: Principles to Practice, 1st ed.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2010; pp. 32, 39, 42, 49, 50, 52. ISBN 978-1-4051-9247-7. [Google Scholar]

| Group M | Group V | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 8.80 (SD = 3.09) | 8.73 (SD = 3.04) | 0.94 | |

| Sex (%): | Male | 60.00 | 54.84 | 0.68 |

| Female | 40.00 | 45.16 | ||

| Breed: | Crossbreed | 9 | 11 | |

| Cocker Spaniel | 5 | 5 | 0.90 | |

| Other | 16 | 15 | ||

| Body Condition Score (/9) | 5 (IQR 4–7) | 5 (IQR = 4–6) | 0.94 | |

| Bodyweight (kg) | 22.48 (SD = 10.34) | 21.62 (SD = 8.86) | 0.73 | |

| ASA I | 0 | 1 | ||

| ASA II | 24 | 23 | >0. | |

| ASA III | 6 | 7 | ||

| Reason for CT: | Oncological | 65.63 | 62.50 | 0.80 |

| Other | 34.37 | 37.50 | ||

| Concurrent Medication (%) | 43.33 | 58.06 | 0.25 | |

| Group M | Group V | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dexmedetomidine Dose (µg kg−1) | 2 (IQR = 2–2.25) | 2 (IQR = 2–2) | 0.85 |

| Methadone Dose (mg kg−1) | 0.2 (IQR = 0.2–0.2) | 0.2 (IQR = 0.2–0.2) | >0. |

| Other Premedication Agents (%) | 13.33 | 9.68 | 0.71 |

| Propofol Dose (mg kg−1) | 2.00 (IQR = 1.50–2.53) | 2.00 (IQR = 1.60–2.12) | 0.997 |

| Premedication to Induction (min) | 11.50 (IQR = 7.75–13.00) | 9.00 (IQR = 7.00–12.25) | 0.30 |

| Induction to Apnoea (min) | 21.00 (IQR = 17.00–27.00) | 17.00 (IQR 16.00–24.50) | 0.10 |

| ETiso Baseline (%) | 1.00 (IQR = 0.97–1.03) | 1.00 (IQR = 0.98–1.03) | 0.63 |

| ETiso Post-Intervention (%) | 0.99 (IQR = 0.92–1.02) | 0.96 (IQR = 0.94–1.00) | 0.33 |

| Group M | Group V | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apnoea success (%) | 93.55 | 76.67 | 0.08 |

| Apnoea onset (s) | 30.00 (IQR = 20.00–35.00) | 0.00 (IQR = 0.00–0.00) | <0.0001 |

| Apnoea duration (s) | 69.00 (IQR = 40.00–120.00) | 120.00 (IQR = 86.50–120.00) | <0.001 |

| Heart rate baseline (bpm) | 74.00 (IQR = 64.50–84.00) | 59.50 (IQR = 52.50–72.25) | 0.02 |

| Heart rate post-intervention (bpm) | 89.50 (IQR = 71.75–100.00) | 68.00 (IQR = 51.50–78.50) | 0.0004 |

| Heart rate absolute change (bpm) | 12.63 (SD = 9.87) | 5.72 (SD = 6.60) | 0.002 |

| Heart rate percentage change (%) | +19.16 (SD = 16.68) | +9.62 (SD = 11.04) | 0.01 |

| MAP baseline (mmHg) | 82.65 | 91.87 | 0.008 |

| MAP post-intervention (mmHg) | 75.87 | 85.69 | 0.002 |

| MAP absolute change (mmHg) | −6.50 (IQR = −9.25–−2.75) | −6.50 (IQR = −10.00–−3.00) | 0.83 |

| MAP percentage change (%) | −7.30 (IQR = −11.66–−3.13) | −7.62 (IQR = −9.79–−3.81) | 0.81 |

| Respiratory rate baseline (bpm) | 12.00 (IQR = 8.00–15.00) | 13.00 (IQR = 12.00–16.00) | 0.01 |

| Respiratory rate post-intervention (bpm) | 7.00 (IQR = 4.00–10.50) | 13.00 (IQR = 12.00–17.00) | <0.0001 |

| ETCO2 baseline (mmHg) | 52.50 (IQR = 49.88–60.25) | 40.00 (IQR = 39.00–40.00) | <0.0001 |

| ETCO2 post-intervention (mmHg) | 59.00 (IQR = 57.00–63.25) | 45.50 (IQR = 45.00–47.25) | <0.0001 |

| ETCO2 absolute change (mmHg) | 7.00 (IQR = 3.50–11.00) | 6.00 (IQR = 4.88–8.25) | 0.43 |

| ETCO2 percentage change (%) | 12.61 (IQR = 6.66–21.68) | 15.00 (IQR = 12.46–20.23) | 0.10 |

| SpO2 baseline (%) | 97.00 (IQR = 96.00–99.00) | 98.00 (IQR = 96.00–98.00) | 0.71 |

| SpO2 post-intervention (%) | 97.00 (IQR = 96.00–98.25) | 97.00 (IQR = 96.00–99.00) | 0.66 |

| Group M | Group V | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory Motion (% of cases) | 19.23 | 7.41 | 0.25 |

| Total Lung Volume (TLV) (cm3) | 1012 (IQR = 698.4–1553) | 951.4 (IQR = 566.4–1274) | 0.51 |

| TLV/Body Weight (cm3 kg−1) | 48.44 (IQR = 35.92–61.76) | 48.04 (IQR = 36.83–60.68) | 0.91 |

| Aerated Lung Volume (ALV) (cm3) | 1100 (SD = 116.5) | 1018 (SD = 106.9) | 0.61 |

| ALV/Body Weight (cm3 kg−1) | 48.08 (IQR = 35.85–61.61) | 47.95 (IQR = 36.82–60.66) | 0.88 |

| Non-Aerated Lung Volume (NLV) (cm3) | 3.66 (IQR = 1.11–5.47) | 1.49 (IQR = 0.39–2.60) | 0.02 |

| NLV/Body Weight (cm3 kg−1) | 0.14 (IQR = 0.09–0.22) | 0.10 (IQR = 0.02–0.13) | 0.03 |

| Aeration (%) | 99.68 (IQR = 99.53–99.79) | 99.82 (IQR = 99.68–99.96) | 0.01 |

| Attenuation of Total Lung Volume (HU) | −724.2 (IQR = −750.0–−679.1) | −716.1 (IQR = −760.7–−676.9) | 0.84 |

| Attenuation of Aerated Lung Volume (HU) | −724.9 (IQR = −751.8–−679.8) | −714.3 (IQR = −760.8–−677.2) | 0.87 |

| Number of Lobes with Atelectasis | 2.00 (IQR = 1.00–3.25) | 1.00 (IQR = 1.00–2.00) | 0.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hordle, T.; Navarro-Carrillo, M.; Schofield, I.; Plested, M.; Niimura del Barrio, M.C. A Comparison of Two Different Methods for Inducing Apnoea During Thoracic Computed Tomography of Dogs. Animals 2025, 15, 1014. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15071014

Hordle T, Navarro-Carrillo M, Schofield I, Plested M, Niimura del Barrio MC. A Comparison of Two Different Methods for Inducing Apnoea During Thoracic Computed Tomography of Dogs. Animals. 2025; 15(7):1014. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15071014

Chicago/Turabian StyleHordle, Thomas, Maria Navarro-Carrillo, Imogen Schofield, Mark Plested, and Maria Chie Niimura del Barrio. 2025. "A Comparison of Two Different Methods for Inducing Apnoea During Thoracic Computed Tomography of Dogs" Animals 15, no. 7: 1014. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15071014

APA StyleHordle, T., Navarro-Carrillo, M., Schofield, I., Plested, M., & Niimura del Barrio, M. C. (2025). A Comparison of Two Different Methods for Inducing Apnoea During Thoracic Computed Tomography of Dogs. Animals, 15(7), 1014. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15071014