Evaluation of Serum Iron and Platelet Parameters in Dogs

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

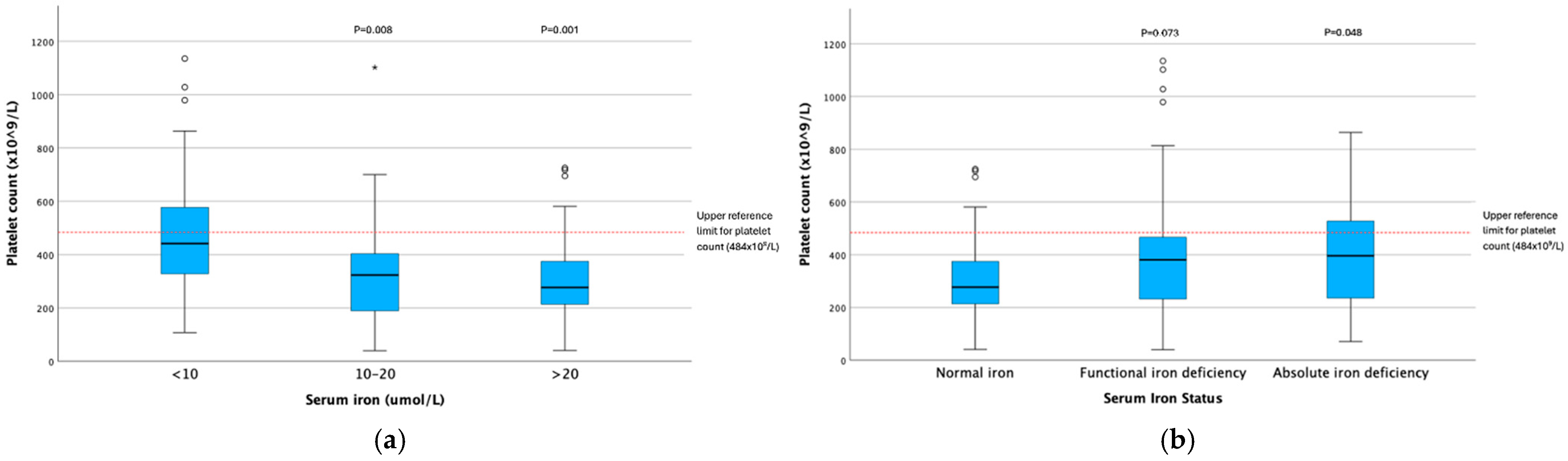

3.2. Platelet Parameter and Serum Iron Concentration Analysis

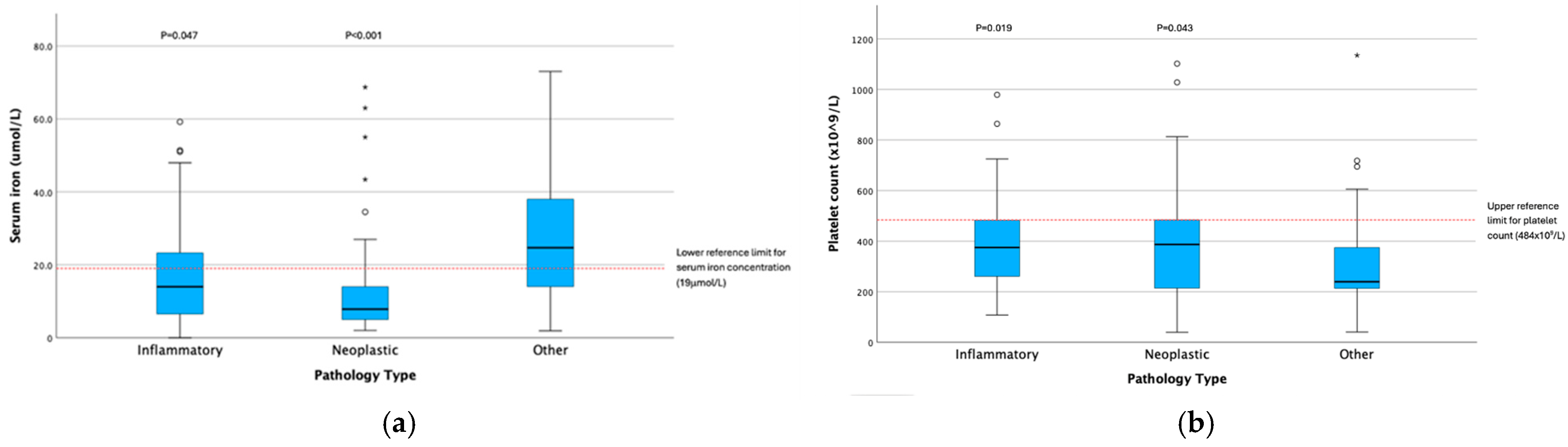

3.3. Disease Pathology and Serum Iron Concentration Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBC | Complete blood count |

| MPV | Mean platelet volume |

| TIBC | Total iron binding capacity |

| ME | Male entire |

| MN | Male neutered |

| FE | Female entire |

| FN | Female neutered |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| SE | Standard error |

| t/F/H/U | Test statistics (Pearson Chi2/Quade-ANOVA/Kruskal–Wallis/Mann–Whitney) |

| df | Degrees of freedom |

| DFH | Hypothesis degrees of freedom |

| DFE | Effective degrees of freedom |

| MW | Mann–Whitney |

| KW | Kruskal–Wallis |

References

- Moreno, C.J.A.; Romero, C.M.S.; Gutiérrez, M.M. Classification of anemia for gastroenterologists. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 4627–4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, V.; Lubas, G.; Lombardo, A.; Corazza, M.; Guidi, G.; Cardini, G. Evaluation of erythrocytes, platelets, and serum iron profile in dogs with chronic enteropathy. Vet. Med. Int. 2010, 2010, 716040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCown, J.L.; Specht, A.J. Iron homeostasis and disorders in dogs and cats: A review. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2011, 47, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naigamwalla, D.Z.; Webb, J.A.; Giger, U. Iron deficiency anemia. Can. Vet. J. 2012, 53, 250–256. [Google Scholar]

- Matur, E.; Ekiz, E.E.; Erek, M.; Ergen, E.; Kucuk, S.H.; Erhan, S.; Özcan, M. Relationship between anemia, iron deficiency, and platelet production in dogs. Med. Weter. 2019, 75, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristic, J.M.; Stidworthy, M.F. Two cases of severe iron-deficiency anaemia due to inflammatory bowel disease in the dog. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2002, 43, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, A.A. Diagnosis of disorders of iron metabolism in dogs and cats. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2013, 43, 1319–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, B.F.; Keen, C.L.; Kaneko, J.J.; Farver, T.B. Anemia of inflammatory disease in the dog: Measurement of hepatic superoxide dismutase, hepatic nonheme iron, copper, zinc, and ceruloplasmin and serum iron, copper, and zinc. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1981, 42, 1114–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, B.F.; Kaneko, J.J.; Farver, T.B. Anemia of inflammatory disease in the dog: Availability of storage iron in inflammatory disease. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1981, 42, 586–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokkam, V.R.; Killeen, R.B.; Kotagiri, R. Secondary Thrombocytosis; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Neel, J.A.; Snyder, L.; Grindem, C.B. Thrombocytosis: A retrospective study of 165 dogs. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2012, 41, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, L.V.; Polizopoulou, Z.S.; Papavasileiou, E.G.; Mpairamoglou, E.L.; Kantere, M.C.; Rousou, X.A. Magnitude of reactive thrombocytosis and associated clinical conditions in dogs. Vet. Rec. 2017, 181, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhadgut, H.; Galadima, H.; Tahhan, H.R. Thrombocytosis in Iron Deficiency Anemia. Blood 2018, 13, 4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voudoukis, E.; Karmiris, K.; Oustamanolakis, P.; Theodoropoulou, A.; Sfiridaki, A.; Paspatis, G.A.; Koutroubakis, I.E. Association between thrombocytosis and iron deficiency anemia in inflammatory bowel disease. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 25, 1212–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulnigg-Dabsch, S.; Schmid, W.; Howaldt, S.; Stein, J.; Mickisch, O.; Waldhor, T.; Evstatiev, R.; Kamali, H.; Volf, I.; Gasche, C. Iron deficiency generates secondary thrombocytosis and platelet activation in IBD: The randomized, controlled thromboVIT trial. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 1609–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawasugi, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Shirafuji, N.; Oka, Y. Increased Levels of Thrombopoietin and IPF in Patients with Iron Deficiency Anemia. Blood 2014, 124, 5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keung, Y.K.; Owen, J. Iron deficiency and thrombosis: Literature review. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2004, 10, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchini, M.; Targher, G.; Montagnana, M.; Lippi, G. Iron and thrombosis. Ann. Hematol. 2008, 87, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evstatiev, R. Iron deficiency, thrombocytosis and thromboembolism. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2016, 166, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, A.B.; Kuter, D.J.; Al-Samkari, H. Characterization of the rate, predictors, and thrombotic complications of thrombocytosis in iron deficiency anemia. Am. J. Hematol. 2020, 95, 1180–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, K.; Yadav, V.; Margekar, S.L.; Bansal, P.; Aggarwal, R.; Gupta, A.; Ghotekar, L.H. Iron Deficiency Anemia as a Potential Risk Factor for Unprovoked DVT in Young Patients: A Case Series. J. Assoc. Physicians India 2023, 71, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, A.S. Thrombocytosis in dogs and cats: A retrospective study. Comp. Haematol. Int. 1991, 1, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolcock, A.D.; Keenan, A.; Cheung, C.; Christian, J.A.; Moore, G.E. Thrombocytosis in 715 Dogs (2011–2015). J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2017, 31, 1691–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radakovich, L.B.; Pannone, S.C.; Truelove, M.P.; Olver, C.S.; Santangelo, K.S. Hematology and biochemistry of aging-evidence of “anemia of the elderly” in old dogs. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2017, 46, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K.; Lamb, W.A. Idiopathic thrombocytopenia in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. Aust. Vet. J. 2005, 83, 700–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evstatiev, R.; Bukaty, A.; Jimenez, K.; Kulnigg-Dabsch, S.; Surman, L.; Schmid, W.; Eferl, R.; Lippert, K.; Scheiber-Mojdehkar, B.; Kvasnicka, H.M.; et al. Iron defiency alters megakaryopoiesis and platelet phenotype independent of thrombopoietin. Am. J. Hematol. 2014, 89, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babikir, M.; Ahmad, R.; Soliman, A.; Al-Tikrity, M.; Yassin, M.A. Iron-induced thrombocytopenia: A mini-review of the literature and suggested mechanisms. Cureus 2020, 12, e10201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadikoylu, G.; Yavasoglu, I.; Bolaman, Z.; Senturk, T. Platelet parameters in women with iron deficiency anemia. J. Natl. Assoc. 2006, 98, 398–402. [Google Scholar]

- Nairz, M.; Theurl, I.; Wolf, D.; Weiss, G. Iron deficiency or anemia of inflammation?: Differential diagnosis and mechanisms of anemia of inflammation. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2016, 166, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouri, S.; Martin, J. Investigation of iron deficiency anaemia. Clin. Med. 2018, 18, 242–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soppi, E.T. Iron deficiency without anemia—A clinical challenge. Clin. Case Rep. 2018, 6, 1082–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawsat, G.A.; Fry, M.M.; Behling-Kelly, E.; Olin, S.J.; Schaefer, D.M.W. Bone marrow iron scoring in healthy and clinically ill dogs with and without evidence of iron-restricted erythropoiesis. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2023, 52, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzón, H.; Forné, M.; González, C.; Esteve, M.; Martí, J.M.; Rosinach, M.; Mariné, M.; Loras, C.; Espinós, J.C.; Salas, A.; et al. Mild enteropathy as a cause of iron-deficiency anaemia of previously unknown origin. Dig. Liver Dis. 2011, 43, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naoum, F.A. Iron deficiency in cancer patients. Rev. Bras. Hematol. Hemoter. 2016, 38, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AI Amin, A.S.M.; Gupta, V. Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin); StatPearls Publishing [Internet]: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kather, S.; Grützner, N.; Kook, P.H.; Dengler, F.; Heilmann, R.M. Review of cobalamin status and disorders of cobalamin metabolism in dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butkiewicz, A.; Kemona, H.; Dymicka-Piekarska, V.; Matowicka-Karna, J.; Radziwon, P.; Lipska, A. Platelet count, mean platelet and thrombocytopoeitic indices in healthy women and men. Thromb. Res. 2006, 118, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukar, A.; Waziri, G.; Buhari, M.A.; Askira, U.M.; Stephen, L.; Obi, O.S. Assessment of platelet counts in women using hormonal contraceptives visiting state specialist hospital Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria. Haematol. J. Bangladesh 2025, 9, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, J.A.; Peck, J.D.; Deschamps, D.R.; McIntosh, J.J.; Knudtson, E.J.; Terrell, D.R.; Vesely, S.K.; George, J.N. Platelet counts during pregnancy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Category | Total No. (%) of Dogs | No. (%) Dogs in Serum Iron Categories | Pearson Chi2 Comparisons for Iron Deficiency Categories | No. (%) of Dogs with Thrombocytosis (Plt > 484 × 109/L) | Pearson Chi2 Comparisons for Thrombocytosis Categories | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Serum Iron | Functional Iron Deficiency | Absolute Iron Deficiency | t (df) | p | t (df) | p | ||||

| Sex | Female | 57 (40.7) | 23 (42.6) | 23 (41.1) | 11 (36.7) | 0.286 (2) | 0.867 | 10 (37.0) | 0.187 (1) | 0.665 |

| Male | 83 (59.3) | 31 (57.4) | 33 (58.8) | 19 (63.3) | 17 (63.0) | |||||

| Unknown | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | |||||

| Age (years) | <6 | 40 (28.6) | 14 (25.9) | 19 (33.9) | 3.271 (4) | 0.514 | 9 (33.3) | 2.195 (2) | 0.334 | |

| 6–10 | 59 (42.1) | 26 (48.1) | 22 (39.3) | 8 (29.6) | ||||||

| >10 | 41 (29.3) | 14 (25.9) | 15 (26.8) | 10 (37.0) | ||||||

| Unknown | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | |||||

| Affected Body System | Gastrointestinal | 71 (51.8) | 16 (30.2) | 35 (63.6) | 20 (69.0) | 16.423 (2) | <0.001 *1 | 18 (66.7) | 2.967 (1) | 0.085 |

| Other | 66 (48.2) | 37 (69.8) | 20 (36.4) | 9 (31.0) | 9 (33.3) | |||||

| Unknown | 4 | - | - | - | 4 | |||||

| Pathology Type | Inflammatory | 45 (32.8) | 14 (26.4) | 16 (29.1) | 15 (51.7) | 30.671 (4) | <0.001 *2 | 10 (37.0) | 1.656 (2) | 0.437 |

| Neoplastic | 42 (30.7) | 7 (13.2) | 28 (50.9) | 7 (24.1) | 10 (37.0) | |||||

| Other | 50 (36.5) | 32 (60.4) | 11 (20.0) | 7 (24.1) | 7 (25.9) | |||||

| Unknown | 4 | - | - | - | 4 | |||||

| Serum B12 (ng/L) | <300 | 22 (47.8) | 7 (38.9) | 12 (57.1) | 3 (2.9) | 1.376 (2) | 0.503 | 3 (50.0) | 0.013 (1) | 0.909 |

| >300 | 24 (52.2) | 11 (61.1) | 9 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | 3 (50.0) | |||||

| Unknown | 95 | - | - | - | 95 | |||||

| Haematocrit (%) | <20 | 54 (38.8) | 24 (43.6) | 20 (36.4) | 10 (34.5) | 8.218 (4) | 0.084 | 11 (42.3) | 3.404 (2) | 0.182 |

| 20–30 | 44 (31.7) | 11 (20.0) | 24 (43.6) | 9 (31.0) | 11 (42.3) | |||||

| >30 | 41 (29.5) | 20 (36.4) | 11 (20.0) | 10 (34.5) | 4 (5.4) | |||||

| Unknown | 2 | - | - | - | 2 | |||||

| Platelet Count (×109/L) | <250 | 50 (35.5) | 26 (47.3) | 16 (28.6) | 8 (26.7) | 10.248 (4) | 0.036 *3 | - | - | - |

| 250–400 | 42 (29.8) | 18 (32.7) | 17 (30.4) | 7 (23.3) | - | |||||

| 400 | 49 (34.8) | 11 (20.0) | 23 (41.1) | 15 (50.0) | - | |||||

| Unknown | 0 | - | - | - | - | |||||

| MPV (fl) | <11 | 29 (32.2) | 11 (31.4) | 13 (35.1) | 5 (27.8) | 0.411 (4) | 0.982 | 10 (52.6) | - | - |

| 11–15 | 32 (35.6) | 13 (37.1) | 12 (32.4) | 7 (38.9) | 5 (26.3) | |||||

| >15 | 29 (32.2) | 11 (31.4) | 12 (32.4) | 6 (33.3) | 4 (21.1) | |||||

| Unknown | 51 | - | - | - | 51 | |||||

| TIBC (μmol/L) | <55 | 50 (36.8) | 18 (36.0) | 32 (57.1) | 0 | - | - | 6 (22.2) | 3.138 (2) | 0.208 |

| 55–70 | 43 (31.6) | 19 (38.0) | 24 (42.9) | 0 | 10 (37.0) | |||||

| >70 | 43 (31.6) | 13 (26.0) | 0 | 30 (100) | 11 (40.7) | |||||

| Unknown | 5 | - | - | - | 5 | |||||

| Transferrin Saturation (%) | <25 | 64 (47.4) | 0 | 37 (66.1) | 27 (90.0) | - | - | 16 (59.3) | 1.901 (1) | 0.168 |

| >25 | 71 (52.6) | 49 (100) | 19 (3.9) | 3 (10.0) | 11 (40.7) | |||||

| Unknown | 6 | - | - | - | 6 | |||||

| Serum iron concentration (μmol/L) | <10 | 48 (34.0) | 0 | 31 (55.4) | 17 (56.7) | - | - | 15 (55.6) | 8.207 (2) | 0.017 *4 |

| 10–20 | 40 (28.4) | 5 (9.1) | 25 (44.6) | 13 (43.3) | 3 (11.1) | |||||

| >20 | 53 (37.6) | 50 (90.9) | 0 | - | 9 (33.3) | |||||

| Unknown | 0 | - | - | - | 0 | |||||

| Variables | Subcategories | t | DFH/DFE | p | Post-hoc Comparisons | t (df) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum iron concentration category (μmol/L) vs. platelet count category | <10 | 4.526 | 2/132 | 0.013 *1 | <10 vs. 10–20 | 2.489 (132) | 0.014 |

| 10–20 | <10 vs. >20 | 2.678 (132) | 0.008 | ||||

| >20 | 10–20 vs. >20 | 0.005 (132) | 0.996 | ||||

| Iron deficiency category vs. platelet count category | None | 1.741 | 2/132 | 0.179 *1 | - | - | - |

| Functional | - | - | - | ||||

| Absolute | - | - | - | ||||

| Serum iron concentration category (μmol/L) vs. continuous platelet count | <10 | 6.185 | 2/132 | 0.003 *1 | <10 vs. 10–20 | 3.173 (132) | 0.002 |

| 10–20 | <10 vs. >20 | 2.854 (132) | 0.005 | ||||

| >20 | 10–20 vs. >20 | −0.522 (132) | 0.603 | ||||

| Iron deficiency category vs. continuous platelet count data | None | 1.349 | 2/132 | 0.263 *1 | - | - | - |

| Functional | - | - | - | ||||

| Absolute | - | - | - |

| Variable | Raw Data | KW Comparisons | Post-hoc Comparisons | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum Iron Category (μmol/L) | Number of Dogs | Median | IQR (Min–Max) | Number of Dogs in Analysis | t (df) | p | Category Comparisons Between Iron Subgroups | t | SE | Standard t | p | Adj. p | |

| Haematocrit (l/l) | <10 | 47 | 20.7 | 12 (8–40) | 139 | 7.714 (2) | 0.021 | <10 vs. 10–20 | –20.717 | 8.722 | −2.375 | 0.018 | 0.053 |

| 10–20 | 39 | 28.3 | 17 (10–44) | <10 vs. >20 | –19.519 | 8.068 | −2.419 | 0.016 | 0.047 | ||||

| >20 | 53 | 26.3 | 20 (7–80) | 10–20 vs. >20 | 1.197 | 8.495 | 0.141 | 0.888 | 1.000 | ||||

| Platelet Count × 109/L | <10 | 48 | 442 | 266 (108–1135) | 141 | 14.726 (2) | <0.001 | <10 vs. 10–20 | 26.423 | 8.743 | 3.022 | 0.003 | 0.008 |

| 10–20 | 40 | 324 | 225 (40–1102) | <10 vs. >20 | 28.804 | 8.137 | 3.540 | <0.001 | 0.001 | ||||

| >20 | 53 | 277 | 162 (41–725) | 10–20 vs. >20 | 2.381 | 8.554 | 0.278 | 0.781 | 1.000 | ||||

| MPV (fl) | <10 | 30 | 14.5 | 6.8 (7.9–20.1) | 90 | 2.172 (2) | 0.338 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 10–20 | 27 | 11.5 | 5.6 (6.3–18.7) | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| >20 | 33 | 12.4 | 6.5 (8.1–23.8) | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Serum B12 (pg/mL) | <10 | 14 | 245 | 137 (125–965) | 46 | 5.755 (2) | 0.056 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 10–20 | 16 | 310 | 248 (74–1359) | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| >20 | 16 | 373 | 376 (142–1523) | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Variable | Raw Data | KW Comparisons | Post-hoc Comparisons | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron Deficiency Category | Number of Dogs | Median | IQR (Min–Max) | Number of Dogs in Analysis | t (df) | p | Category Comparisons Between Iron Subgroups | t | SE | Sdandard t | p | Adj. Sig. | |

| Haematocrit (l/l) | None | 55 | 24.9 | 20 (7–80) | 139 | 0.355 (2) | 0.837 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Functional | 55 | 24.0 | 11 (10–44) | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Absolute | 29 | 25.6 | 19 (8–41) | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Platelet Count × 109/L | None | 55 | 277 | 162 (41–725) | 141 | 7.654 (2) | 0.022 | None vs. Functional | –17.458 | 7.753 | 2.252 | 0.024 | 0.073 |

| Functional | 56 | 381 | 239 (40–1135) | None vs. Absolute | –22.315 | 9.269 | 2.407 | 0.016 | 0.048 | ||||

| Absolute | 30 | 396 | 298 (71–864) | Functional vs. Absolute | –4.857 | 9.240 | 0.526 | 0.599 | 1.000 | ||||

| MPV (fl) | None | 35 | 12.4 | 7 (6–24) | 90 | 0.395 (2) | 0.873 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Functional | 37 | 12.8 | 7 (8–20) | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Absolute | 18 | 13.5 | 5 (8–19) | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Serum B12 (pg/mL) | None | 18 | 332 | 331 (100–1523) | 46 | 2.419 (2) | 0.298 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Functional | 21 | 277 | 195 (74–1359) | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Absolute | 7 | 506 | 755 (125–1322) | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Variables | Subcategories | t | DFH/DFE | p | Post-hoc Comparisons | t (df) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body system vs. serum iron concentration category | Gastrointestinal | 2.147 | 1/133 | 0.145 *1 | - | - | - |

| Other | - | - | - | ||||

| Body system vs. iron deficiency category | Gastrointestinal | 1.302 | 1/133 | 0.256 *1 | - | - | - |

| Other | - | - | - | ||||

| Body system vs. continuous serum iron data | Gastrointestinal | 3.626 | 1/133 | 0.059 *1 | - | - | - |

| Other | - | - | - | ||||

| Body system vs. platelet category | Gastrointestinal | 0.006 | 1/133 | 0.939 *2 | - | - | - |

| Other | - | - | - | ||||

| Body system vs. continuous platelet count | Gastrointestinal | 0.000 | 1/133 | 0.985 *2 | - | - | - |

| Other | - | - | - | ||||

| Pathology type vs. serum iron concentration category | Inflammatory | 8.449 | 2/132 | <0.001 *3 | Serum iron <10 vs. 10–20 | 3.733 (132) | <0.001 |

| Neoplastic | Serum iron 10–20 vs. >20 | 0.448 (132) | 0.655 | ||||

| Other | Serum iron <10 vs. >20 | −3.423 (132) | 0.001 | ||||

| Pathology type vs. iron deficiency category | Inflammatory | 0.841 | 2/132 | 0.434 *3 | - | - | - |

| Neoplastic | - | - | - | ||||

| Other | - | - | - | ||||

| Pathology type vs. continuous serum iron data | Inflammatory | 7.449 | 2/132 | 0.001 *3 | Inflammatory vs. neoplastic | 3.657 (132) | <0.001 |

| Neoplastic | Inflammatory vs. other | 0.827 (132) | 0.410 | ||||

| Other | Neoplastic vs. other | −2.969 (132) | 0.004 | ||||

| Pathology type vs. platelet count category | Inflammatory | 0.668 | 2/132 | 0.515 *4 | - | - | - |

| Neoplastic | - | - | - | ||||

| Other | - | - | - | ||||

| Pathology type vs. continuous platelet count data | Inflammatory | 0.360 | 2/132 | 0.698 *4 | - | - | - |

| Neoplastic | - | - | - | ||||

| Other | - | - | - |

| Variable | Raw Data | MW Comparisons | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body System Category | n | Median | IQR (Min–Max) | Number of Dogs in Analysis | t | SE | Standard t | p | |

| Serum iron concentration (μmol/L) | Gastrointestinal | 71 | 11 | 14 (0–59) | 137 | 3234.5 | 232.029 | 3.842 | <0.001 |

| Other | 66 | 22 | 29 (2–73) | ||||||

| Platelet Count × 109/L | Gastrointestinal | 71 | 375 | 288 (40–1102) | 137 | 1763 | 232.092 | −2.499 | 0.012 |

| Other | 66 | 315 | 191 (41–1135) | ||||||

| Variable | Raw Data | KW Comparisons | Post-hoc Comparisons | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Pathology Category | n | Median | IQR (Min-Max) | Number of Dogs in Analysis | t (df) | p | Category Comparisons Between Iron Subgroups | t | SE | Standard t | p | Adj. p | |

| Serum iron concentration (μmol/L) | Inflammatory | 45 | 14 | 17.4 (0–59) | 137 | 19.178 (2) | <0.001 | N-O | −36.177 | 8.304 | −4.357 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Neoplastic | 42 | 8 | 9 (2–69) | I-O | −19.726 | 8.152 | −2.420 | 0.016 | 0.047 | ||||

| Other | 50 | 25 | 24 (2–73) | N-I | 16.452 | 8.512 | 1.933 | 0.053 | 0.160 | ||||

| Platelet Count × 109/L | Inflammatory | 45 | 375 | 227 (108–979) | 137 | 9.232 (2) | 0.010 | N-O | 20.324 | 8.306 | 2.447 | 0.014 | 0.043 |

| Neoplastic | 42 | 387 | 283 (40–1102) | I-O | 22.283 | 8.154 | 2.733 | 0.006 | 0.019 | ||||

| Other | 50 | 240 | 164 (41–1135) | N-I | 1.960 | 8.514 | 0.230 | 0.818 | 1.000 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lubbers, C.; Corvers, T.A.M.; Dye, C. Evaluation of Serum Iron and Platelet Parameters in Dogs. Animals 2025, 15, 3613. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243613

Lubbers C, Corvers TAM, Dye C. Evaluation of Serum Iron and Platelet Parameters in Dogs. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3613. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243613

Chicago/Turabian StyleLubbers, Charlotte, Tim Andre M. Corvers, and Charlotte Dye. 2025. "Evaluation of Serum Iron and Platelet Parameters in Dogs" Animals 15, no. 24: 3613. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243613

APA StyleLubbers, C., Corvers, T. A. M., & Dye, C. (2025). Evaluation of Serum Iron and Platelet Parameters in Dogs. Animals, 15(24), 3613. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243613