Screening of Differentially Expressed Genes Related to Growth, Development and Meat Quality Traits of Huanghuai Sheep Based on RNA-Seq Technology

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Collection of Animal Samples

2.3. Growth and Development Traits and Meat Quality

2.4. Determination of Fatty Acids

2.5. Total RNA Extraction

2.6. RNA Sequencing

2.7. Data Processing

2.8. GO and KEGG Functional Enrichment Analysis

2.9. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Validation

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Growth and Development Traits

3.2. Meat Quality

3.3. Fatty Acid Content

3.4. Transcriptome Sequencing Data Analysis

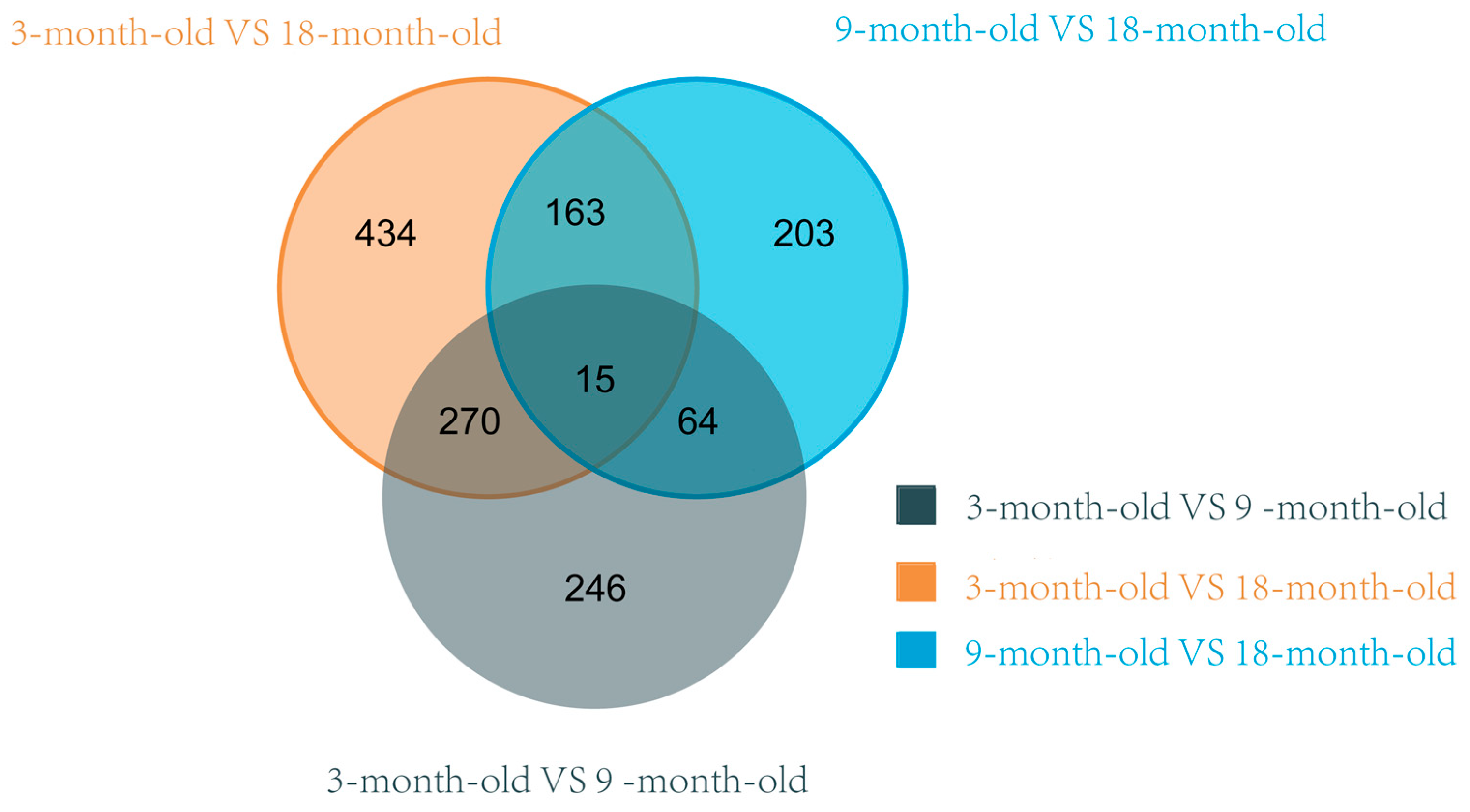

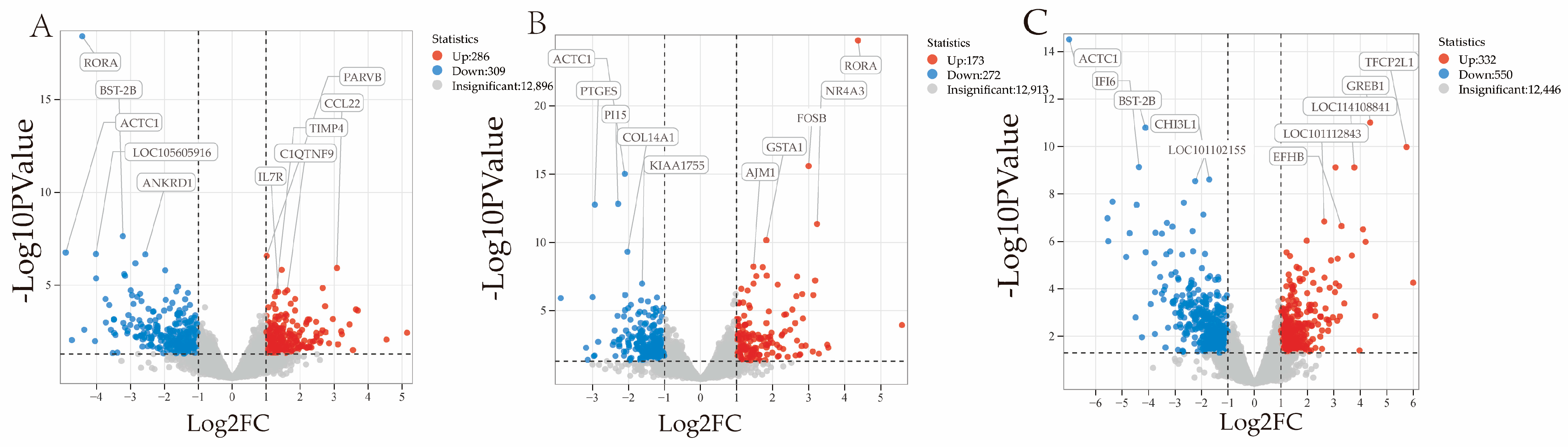

3.5. Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

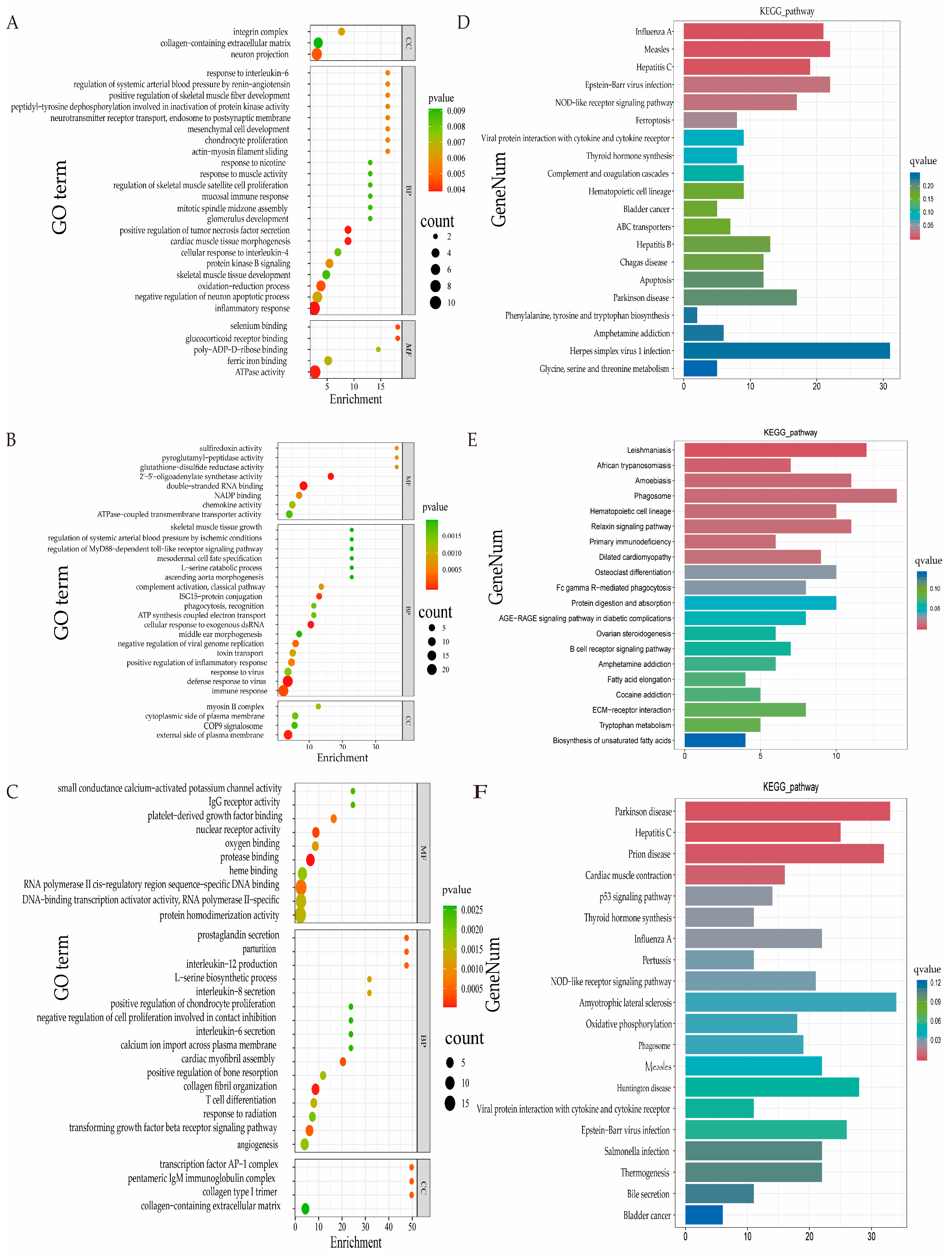

3.6. GO and KEGG Pathway Analyses of DEGs

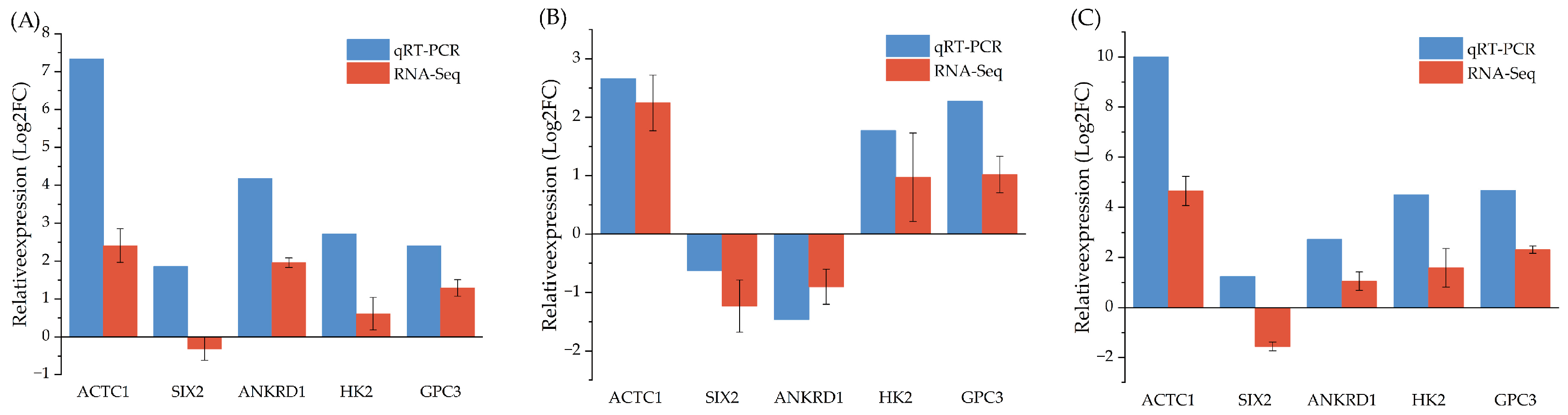

3.7. qRT-PCR Validation

3.8. Correlation Analysis Between Genes Related to Growth, Development, and Meat Quality Traits

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, C.; Blecker, C.; Chen, L.; Xiang, C.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, D. Integrating identification and targeted proteomics to discover the potential indicators of postmortem lamb meat quality. Meat Sci. 2023, 199, 109126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Akhtar, M.F.; Chen, W.; Liu, X.; Zhao, M.; Shi, L.; Khan, M.Z.; Wang, C. Potential candidate genes influencing meat production phenotypic traits in sheep: A review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1616533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Li, A.; Raza, S.H.A. Editorial: Genetic Regulation of Meat Quality Traits in Livestock Species. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1092562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, X.; Wei, H.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, X.; Wang, G.; Ren, C. Indoor feeding combined with restricted grazing time improves body health, slaughter performance, and meat quality in Huang-huai sheep. Anim. Biosci. 2023, 36, 1655–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, K.; Li, J.; Han, H.; Wei, H.; Zhao, J.; Si, H.A.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, D. Review of Huang-huai sheep, a new multiparous mutton sheep breed first identified in China. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2020, 53, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, M.; Zhang, S.; Yang, W.; Li, S.; Cao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ling, Y. Transcriptome analysis revealed the mechanism of skeletal muscle growth and development in different hybrid sheep. Anim. Biosci. 2025, 38, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, Y.; Wu, R.; He, X.; Qin, X.; Chen, L.; Sha, L.; Yun, X.; Nishiumi, T.; Borjigin, G. Integrated Transcriptome Analysis of miRNAs and mRNAs in the Skeletal Muscle of Wuranke Sheep. Genes 2023, 14, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadinejad, F.; Mohammadabadi, M.; Roudbari, Z.; Sadkowski, T. Identification of Key Genes and Biological Pathways Associated with Skeletal Muscle Maturation and Hypertrophy in Bos taurus, Ovis aries, and Sus scrofa. Animals 2022, 12, 3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Wei, T.; Liu, L.X.; Liu, J.Q.; Wang, C.X.; Yuan, Z.Y.; Ma, H.H.; Jin, H.G.; Zhang, L.C.; Cao, Y. Whole-Transcriptome Analysis of Preadipocyte and Adipocyte and Construction of Regulatory Networks to Investigate Lipid Metabolism in Sheep. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 662143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, G.; Li, S.; Zhao, F.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Hu, J.; Shi, B.; Wen, Y.; Zhao, L.; Luo, Y. Comprehensive Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Role of lncRNA in Fatty Acid Metabolism in the Longissimus Thoracis Muscle of Tibetan Sheep at Different Ages. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 847077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Hu, M.; Liu, Z.; Lai, W.; Shi, L.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, H.; Li, Y.; Yan, S. Transcriptome Analysis of the Liver and Muscle Tissues of Dorper and Small-Tailed Han Sheep. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 868717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T/CAAA 080-2022; Meat Sheep Production Performance. China Animal Agriculture Association: Beijing, China, 2022.

- GB/T 41366-2022; Livestock and Poultry Meat Quality Testing—Determination of Moisture, Protein and Fat—Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Method. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Ghosh, S.; Chan, C.K. Analysis of RNA-Seq Data Using TopHat and Cufflinks. In Plant Bioinformatics: Methods and Protocols; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 1374, pp. 339–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Cho, J.; Park, J.; Hwang, J.H. Identification and validation of stable reference genes for quantitative real time PCR in different minipig tissues at developmental stages. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Su, X.; Tian, Y.; Song, G.; Zan, L.; Wang, H. Effect of Actin Alpha Cardiac Muscle 1 on the Proliferation and Differentiation of Bovine Myoblasts and Preadipocytes. Animals 2021, 11, 3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Huang, Q.; Jie, Y.; Sun, C.; Wen, C.; Yang, N. Transcriptomic and epigenomic landscapes of muscle growth during the postnatal period of broilers. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 15, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Li, F.; Zhang, X.; Tian, H.; Ma, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Pu, M.; Cao, P.; Zhang, D.; et al. RNA-Seq and WGCNA Identify Key Regulatory Modules and Genes Associated with Water-Holding Capacity and Tenderness in Sheep. Animals 2025, 15, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Neil, J.A.; Tan, J.P.; Rudraraju, R.; Mohenska, M.; Sun, Y.B.Y.; Walters, E.; Bediaga, N.G.; Sun, G.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Author Correction: A placental model of SARS-CoV-2 infection reveals ACE2-dependent susceptibility and differentiation impairment in syncytiotrophoblasts. Nat. Cell Biol. 2023, 26, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Wan, P.; Wang, H.; Cai, X.; Wang, J.; Chai, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Yang, N.; et al. Transcriptional and open chromatin analysis of bovine skeletal muscle development by single-cell sequencing. Cell Prolif. 2023, 56, e13430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maire, P.; Dos Santos, M.; Madani, R.; Sakakibara, I.; Viaut, C.; Wurmser, M. Myogenesis control by SIX transcriptional complexes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 104, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, Q.H.; Ling, H.; Yew, W.S.; Tan, Z.; Ravikumar, S.; Chang, M.W.; Chai, L.Y.A. The Divergent Immunomodulatory Effects of Short Chain Fatty Acids and Medium Chain Fatty Acids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, D.H.; Kim, J.A.; Lee, J.Y. Mechanisms for the activation of Toll-like receptor 2/4 by saturated fatty acids and inhibition by docosahexaenoic acid. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 785, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, A.M.; Burke, S.; O’Reilly, M.E.; McGillicuddy, F.C.; Costello, D.A. Palmitic Acid and Oleic Acid Differently Modulate TLR2-Mediated Inflammatory Responses in Microglia and Macrophages. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 2348–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Mesallamy, H.O.; Mostafa, A.M.; Amin, A.I.; El Demerdash, E. The interplay of YKL-40 and leptin in type 2 diabetic obese patients. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2011, 93, e113–e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyrgios, I.; Galli-Tsinopoulou, A.; Stylianou, C.; Papakonstantinou, E.; Arvanitidou, M.; Haidich, A.B. Elevated circulating levels of the serum acute-phase protein YKL-40 (chitinase 3-like protein 1) are a marker of obesity and insulin resistance in prepubertal children. Metabolism 2012, 61, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.E.; Yeo, I.J.; Han, S.B.; Yun, J.; Kim, B.; Yong, Y.J.; Lim, Y.S.; Kim, T.H.; Son, D.J.; Hong, J.T. Significance of chitinase-3-like protein 1 in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases and cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazevic, N.; Rogic, D.; Pelajic, S.; Miler, M.; Glavcic, G.; Ratkajec, V.; Vrkljan, N.; Bakula, D.; Hrabar, D.; Pavic, T. YKL-40 as a biomarker in various inflammatory diseases: A review. Biochem. Medica 2024, 34, 010502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Feng, H.; Yousuf, S.; Xie, L.; Miao, X. Differential regulation of mRNAs and lncRNAs related to lipid metabolism in Duolang and Small Tail Han sheep. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Yuan, Z.H.; Li, F.D.; Yue, X.P. Integrating transcriptome and metabolome to identify key genes regulating important muscular flavour precursors in sheep. Animal 2022, 16, 100679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genes | Primer Sequences | Product Length | Genbank Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACTC1 | F: ATTATTGCTCCCCCTGAGCG R: TGAGAGATGAGGGAGGGTGG | 231 bp | NM_001034585.2 |

| ANKRD1 | F: AGCCCAGATCGAATTCCGTG R: GCGGTGCTGAGCAACTTATC | 138 bp | NM_001252178.1 |

| SIX2 | F: ACACAGGTCAGCAACTGGTTCAAG R: GAGTTCTCGCTGTTCTCCCTTTCC | 83 bp | NM_001205678.2 |

| GPC3 | F: CAAGAACTCGTGGAGAGATAC R: CACTTTCATCATTCCATCGC | 273 bp | XM_015105024.4 |

| HK2 | F: TGACGGCACAGAGAAAGGAGACT R: GCACACGCACCAGCAGGA | 77 bp | XM_015094476.2 |

| GAPDH | F: GCAAGTTCCACGGCACAG R: GGTTCACGCCCATCACAA | 249 bp | AJ431207 |

| Sample | Number | Body Height/cm | Body Length/cm | Chest Circumference/cm | Cannon Circumference/cm | Body Weight/kg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 20 | 58.90 ± 1.43 Cc | 63.06 ± 1.34 Cc | 68.18 ± 3.57 Cc | 6.98 ± 0.06 Cc | 26.01 ± 3.77 Cc |

| 9 | 20 | 69.24 ± 1.97 Bb | 80.58 ± 2.03 Bb | 94.29 ± 2.03 Bb | 9.24 ± 1.46 Bb | 53.30 ± 2.57 Bb |

| 18 | 20 | 78.26 ± 1.42 Aa | 90.56 ± 4.76 Aa | 111.34 ± 5.44 Aa | 10.32 ± 0.21 Aa | 98.25 ± 13.84 Aa |

| p value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Sample | Number | Carcass Weight/kg | Dressing Percentage/% | Marbling | Ph | Tenderness/N | GR Value/Mm | Intramuscular Fat/(G/100 g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 3 | 23.67 ± 3.85 Aa | 47.99 ± 1.89 Aa | 1.33 ± 0.28 Aa | 6.66 ± 0.20 Ab | 25.86 ± 1.42 Aa | 9.50 ± 2.65 Aa | 1.27 ± 0.65 Aa |

| 9 | 6 | 44.63 ± 3.94 Ab | 51.56 ± 3.86 Aa | 1.83 ± 0.25 Bb | 6.36 ± 0.11 Aa | 27.46 ± 6.58 Aa | 18.11 ± 4.25 Ab | 1.55 ± 0.64 Aa |

| 18 | 3 | 125.40 ± 20.5 Bc | 61.23 ± 2.15 Bb | 2.83 ± 0.14 Cc | 6.34 ± 0.11 Aa | 28.59 ± 1.33 Aa | 40.00 ± 8.66 Bc | 2.33 ± 1.42 Aa |

| p value | <0.0001 | <0.0014 | <0.0001 | 0.0227 | 0.8013 | 0.0002 | 0.3536 | |

| Sample | Number | C14:0 | C16:0 | C16:1 | C18:0 | C18:1n9c | C18:2n6c | C18:3n3 | C20:1 | C20:2 | C20:4n6 | C24:0 | C23:0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 3 | 2.49 ± 0.53 Aa | 21.77 ± 1.86 Aa | 1.65 ± 0.41 Aa | 17.63 ± 2.32 Aa | 37.00 ± 3.07 Ab | 7.58 ± 1.20 Aa | 0.30 ± 0.03 Aa | 0.32 ± 0.14 Aa | 0.82 ± 0.15 Aa | 4.36 ± 3.13 Aa | 0.81 ± 0.24 Aa | 0.41 ± 0.07 Aa |

| 9 | 6 | 1.84 ± 0.31 Aa | 21.53 ± 0.33 Aa | 2.26 ± 0.44 Aa | 15.50 ± 1.42 Aa | 43.97 ± 1.94 Aa | 7.43 ± 0.92 Aa | 0.32 ± 0.05 Aa | 0.16 ± 0.02 Aa | 0.52 ± 0.17 Ba | 3.26 ± 0.73 Aa | 0.43 ± 0.09 Aa | 0.35 ± 0.03 Aa |

| 18 | 3 | 1.49 ± 0.16 Aa | 24.07 ± 1.15 Aa | 2.21 ± 0.40 Aa | 14.27 ± 0.66 Aa | 46.03 ± 2.58 Aa | 6.44 ± 1.16 Aa | 0.33 ± 0.02 Aa | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.25 ± 0.06 Ba | 1.86 ± 0.72 Aa | 0.25 ± 0.06 Ab | 0.19 ± 0.04 Bb |

| p value | 0.0867 | 0.1702 | 0.3399 | 0.1887 | 0.0289 | 0.5601 | 0.6710 | 0.2927 | 0.0154 | 0.4671 | 0.0279 | 0.0138 | |

| Sample | Total Raw Reads | Clean Reads | Clean Reads Q30 Data/% | Clean Reads NO. | Mapped Reads Rate (%) | Uniquely Mapped Ratio (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 1 | 24,786,184 | 24,336,459 | 94.94 | 48,672,918 | 97.36 | 40,071,244 (91.95%) |

| 2 | 26,379,058 | 25,804,452 | 94.89 | 51,608,904 | 97.51 | 40,067,318 (92.37%) | |

| 3 | 22,891,194 | 22,516,219 | 94.62 | 45,032,438 | 97.25 | 47,969,006 (90.21%) | |

| 9 | 1 | 24,255,211 | 23,854,695 | 94.25 | 47,709,390 | 97.36 | 44,950,518 (92.35%) |

| 2 | 23,786,569 | 23,435,178 | 94.77 | 46,870,356 | 97.40 | 48,227,451 (93.45%) | |

| 3 | 21,628,785 | 21,311,159 | 94.79 | 42,622,318 | 97.30 | 41,620,548 (92.42%) | |

| 18 | 1 | 22,170,943 | 21,788,670 | 94.69 | 43,477,340 | 97.25 | 44,053,786 (92.34%) |

| 2 | 22,103,817 | 21,689,418 | 94.89 | 43,378,836 | 97.34 | 43,223,028 (92.22%) | |

| 3 | 26,963,811 | 26,588,666 | 95.20 | 53,177,332 | 97.90 | 39,490,629 (92.65%) | |

| average | 23,885,064 | 23,480,546 | 94.78 | 46,949,981 | 97.41 | 43,297,059(92.22%) | |

| Group | Expression | Genes | p-Value | Log2FoldChange |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 vs. 9 | Down-regulated gene | RORA | 3.964 × 10−19 | −4.420 |

| BST-2B | 2.297 × 10−8 | −3.222 | ||

| ACTC1 | 1.754 × 10−7 | −4.908 | ||

| LOC105605916 | 2.095 × 10−7 | −4.016 | ||

| ANKRD1 | 2.214 × 10−7 | −2.561 | ||

| Up-regulated genes | PARVB | 2.662 × 10−7 | 1.012 | |

| CCL22 | 1.193 × 10−6 | 3.082 | ||

| C1QYNF9 | 1.924 × 10−5 | 1.618 | ||

| TIMP4 | 2.295 × 10−5 | 1.299 | ||

| IL7R | 2.321 × 10−5 | 1.356 | ||

| 9 vs. 18 | Down-regulated genes | ACTC1 | 9.424 × 10−16 | −2.102 |

| PI15 | 1.502 × 10−13 | −2.289 | ||

| PTGES | 1.718 × 10−13 | −2.934 | ||

| COL14A1 | 4.848 × 10−10 | −2.203 | ||

| KIAA1755 | 1.061 × 10−7 | −1.621 | ||

| Up-regulated genes | RORA | 1.587 × 10−25 | 4.371 | |

| FOSB | 2.543 × 10−16 | 3.000 | ||

| NR4A3 | 4.466 × 10−12 | 3.236 | ||

| GSTA1 | 6.901 × 10−11 | 1.826 | ||

| AJM1 | 6.583 × 10−9 | 1.726 | ||

| 3 vs. 18 | Down-regulated genes | ACTC1 | 3.060 × 10−15 | −6.997 |

| BST-2B | 1.618 × 10−11 | −4.117 | ||

| IFI6 | 7.357 × 10−10 | −4.561 | ||

| CHI3L1 | 2.463 × 10−9 | −1.704 | ||

| LOC101102155 | 2.874 × 10−9 | −2.236 | ||

| Up-regulated genes | GREB1 | 9.820 × 10−12 | 4.375 | |

| TFCP2L1 | 1.049 × 10−10 | 5.748 | ||

| LOC114108841 | 7.586 × 10−10 | 3.773 | ||

| LOC101112843 | 1.448 × 10−7 | 2.636 | ||

| EFHB | 2.281 × 10−7 | 3.290 |

| Category | Term | GO.ID | DEGs | p-Value | Up Gene | Down Gene | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 vs. 9 | BP | cardiac muscle tissue morphogenesis | GO:0042474 | 3 | 0.001901 | ACTC1, ANKRD1, LOC101108995 | |

| BP | inflammatory response | GO:0006954 | 11 | 0.003889 | ACKR2, CCL22, CCR4, NLRP1, TSPAN2 | CHI3L1, LOC101110922, LOC101111911, LOC101120093, LOC101123672, | |

| BP | positive regulation of tumor necrosis factor secretion | GO:1904469 | 3 | 0.003934 | FZD5 | DDX58, IFIH1 | |

| BP | positive regulation of skeletal muscle fiber development | GO:0048743 | 2 | 0.003935 | MYOG, BCL2 | ||

| BP | oxidation-reduction process | GO:0055114 | 6 | 0.004503 | C5H5orf63, COQ10A, FRRS1, LOC101106806 | DUOX1, PIR | |

| BP | actin-myosin filament sliding | GO:0033275 | 2 | 0.005406 | MYBPC1 | ACTC1 | |

| MF | ferric iron binding | GO:0008199 | 4 | 0.006857 | FTL, LOC101117015, LOC114109119, LOC121820289 | ||

| BP | regulation of skeletal muscle satellite cell proliferation | GO:0014842 | 2 | 0.008828 | MYOG, LOC114109370 | ||

| 9 vs. 18 | BP | transforming growth factor beta receptor signaling pathway | GO:0007179 | 6 | 0.0042438 | JUN, WFIKKN2 | COL1A2, COL3A1, HPGD, SMAD6 |

| CC | collagen-containing extracellular matrix | GO:0062023 | 6 | 0.002598 | LOC101119218, SERPINE1 | COL14A1, GPC3, PXDN, POSTN | |

| 3 vs. 18 | BP | mesodermal cell fate specification | GO:0035910 | 2 | 0.001917 | EYA1, SIX2 | |

| BP | skeletal muscle tissue growth | GO:0062023 | 2 | 0.001917 | CHRNA1, CHRND | ||

| CC | collagen-containing extracellular matrix | GO:0042474 | 6 | 0.009131 | HMCN2, PLSCR1, SERPINE1 | ADAMTS2, PLSCR1, SERPINE1 | |

| Month-Old Group | Pathway ID | KO ID | DEGs | p-Value | Up Gene | Down Gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 vs. 9 | Ferroptosis | ko04216 | 8 | 0.000913 | STEAP3, TFRC | ACSL4, FTL, LOC101117015, LOC114109119, LOC121820289, SLC3A2 |

| Thyroid hormone synthesis | ko04710 | 8 | 0.002335 | DUOX1, GPX3, GSR, HSPA5, LOC101117153, LOC121816035, PDIA4, TTF2 | ||

| Hematopoietic cell lineage | ko04640 | 8 | 0.007082 | CD3G, FLT3, IL7R, ITGA1, LOC101106528, LOC101110634, TFRC | LOC105614340 | |

| 9 vs. 18 | Hematopoietic cell lineage | ko04640 | 8 | 0.000207 | LOC101113211 | FCGR1A, IL3RA, KIT, LOC101102230, LOC101109746, LOC101111409, TFRC |

| Osteoclast differentiation | ko04380 | 10 | 0.000995 | FOS, FOSB, JUN, JUNB | BTK, FCGR1A, FCGR3A, LCK, LOC105602100, SOCS3 | |

| Protein digestion and absorption | ko04974 | 9 | 0.001992 | COL23A1, LOC114112700 | COL14A1, COL1A1, COL1A2, COL3A1, COL6A6, EMILIN3, SLC7A8 | |

| Fatty acid elongation | ko00062 | 4 | 0.004381 | LOC101104407, THEM4 | ACOT7, HACD1 | |

| ECM-receptor interaction | ko04512 | 7 | 0.005454 | LOC114112700 | COL1A1, COL1A2, COL6A6, FRAS1, FREM1, LOC101102230 | |

| 3 vs. 18 | Cardiac muscle contraction | ko04260 | 16 | 7.58 × 10−5 | ATP2A2, KEF53_p01, KEF53_p07, KEF53_p10, KEF53_p11, LOC101121285, LOC101121420, LOC121817553, TPM2, TPM3 | ACTC1, ATP1B3, CASQ2, LOC114115573, LOC114117869, TNNI3 |

| Thyroid hormone synthesis | ko04918 | 11 | 0.000619 | ATF4, CD3G | ATP1B3, DUOX1, GSR, HSP90B1, HSPA5, LOC101117153, LOC114117869, LOC121816035, PDIA4 | |

| Oxidative phosphorylation | ko00190 | 18 | 0.001483 | KEF53_p01~13(except 06), LOC101121285, LOC101121420, LOC121817553, NDUFA4 | ATP6V0A1, LOC114115573 |

| Genes | Body Height | Body Length | Chest Circumference | Canno Round | Body Weight | Carcass Weight | Dressing Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTC1 | −0.840 | −0.967 | −0.780 | −0.793 | −0.787 | −0.928 | −0.948 |

| ANKRD1 | −0.654 | −0.856 | −0.573 | −0.591 | −0.561 | −0.787 | −0.913 |

| SIX2 | −0.993 | −0.908 | −1.000 ** | −0.999 * | −1.000 ** | −1.000 ** | −0.952 |

| GPC3 | −0.932 | −0.994 | −0.885 | −0.986 | −0.881 | −0.856 | −0.992 |

| HK2 | −0.978 | −0.999 * | −0.947 | −1.000 ** | −0.945 | −0.927 | −0.999 * |

| HSPA5 | −0.943 | −0.997 * | −0.904 | −0.992 | −0.883 | −0.877 | −1.000 * |

| Genes | Marbling | pH | Tenderness | GR Value/mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COL1A2 | 0.855 | −0.994 | 0.998 * | 0.787 |

| TFRC | −0.946 | 0.55 | −0.692 | −0.977 |

| Genes | IMF | C14:0 | C16:0 | C16:1 | C18:0 | C18:1n9c | C18:2n6c | C18:3n3 | C20:1 | C20:2 | C20:4n6 | C24:0 | C23:0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR2 | −0.846 | 0.982 | −0.827 | −0.979 | 0.997 * | −0.998 * | 0.936 | −0.991 | 0.828 | 0.944 | 0.909 | 0.986 | 0.809 |

| CHI3L1 | −0.879 | 0.992 | −0.861 | −0.963 | 1.000 ** | −1.000 ** | 0.957 | −0.998 * | 0.863 | 0.964 | 0.934 | 0.994 | 0.846 |

| ACOT7 | −0.985 | 0.98 | −0.978 | −0.828 | 0.952 | −0.946 | 1.000* | −0.968 | 0.978 | 0.999 * | 0.999 * | 0.976 | 0.971 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, W.; Song, M.; Gao, F.; Han, H.; Shi, H.; Quan, K.; Li, J. Screening of Differentially Expressed Genes Related to Growth, Development and Meat Quality Traits of Huanghuai Sheep Based on RNA-Seq Technology. Animals 2025, 15, 3612. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243612

Han W, Song M, Gao F, Han H, Shi H, Quan K, Li J. Screening of Differentially Expressed Genes Related to Growth, Development and Meat Quality Traits of Huanghuai Sheep Based on RNA-Seq Technology. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3612. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243612

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Wanli, Mengke Song, Fuxian Gao, Haoyuan Han, Huibin Shi, Kai Quan, and Jun Li. 2025. "Screening of Differentially Expressed Genes Related to Growth, Development and Meat Quality Traits of Huanghuai Sheep Based on RNA-Seq Technology" Animals 15, no. 24: 3612. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243612

APA StyleHan, W., Song, M., Gao, F., Han, H., Shi, H., Quan, K., & Li, J. (2025). Screening of Differentially Expressed Genes Related to Growth, Development and Meat Quality Traits of Huanghuai Sheep Based on RNA-Seq Technology. Animals, 15(24), 3612. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243612