Cladosporium Infection in a Captive Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus): A Rare Case Report from Quanzhou, China

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Living Environment and Clinical Biochemistry Analysis

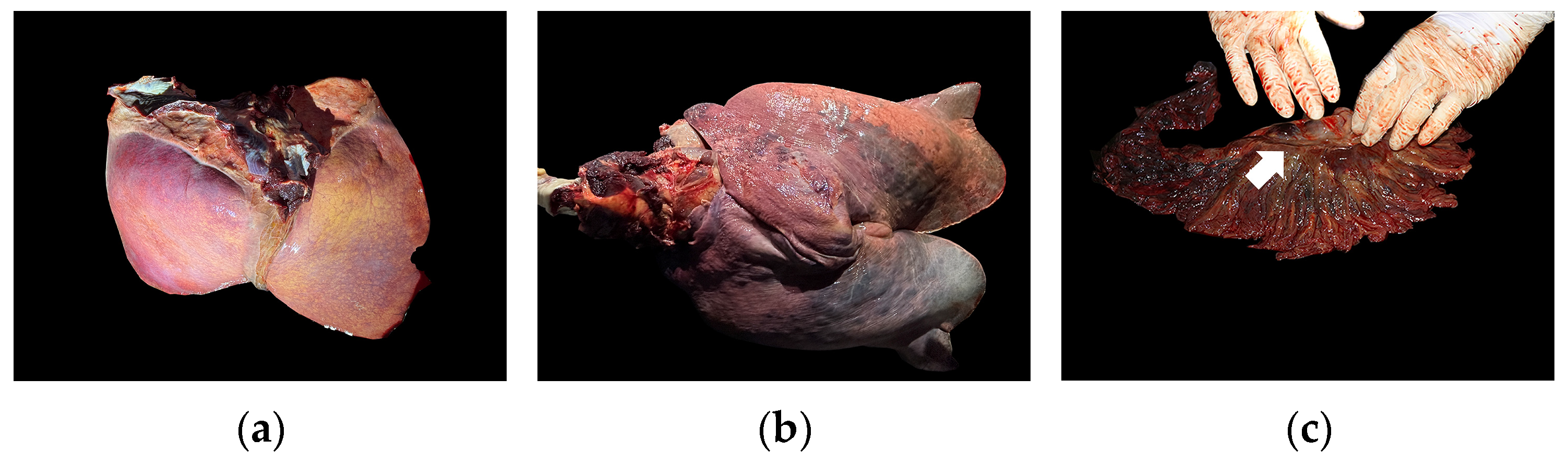

3.2. Post-Mortem Examination

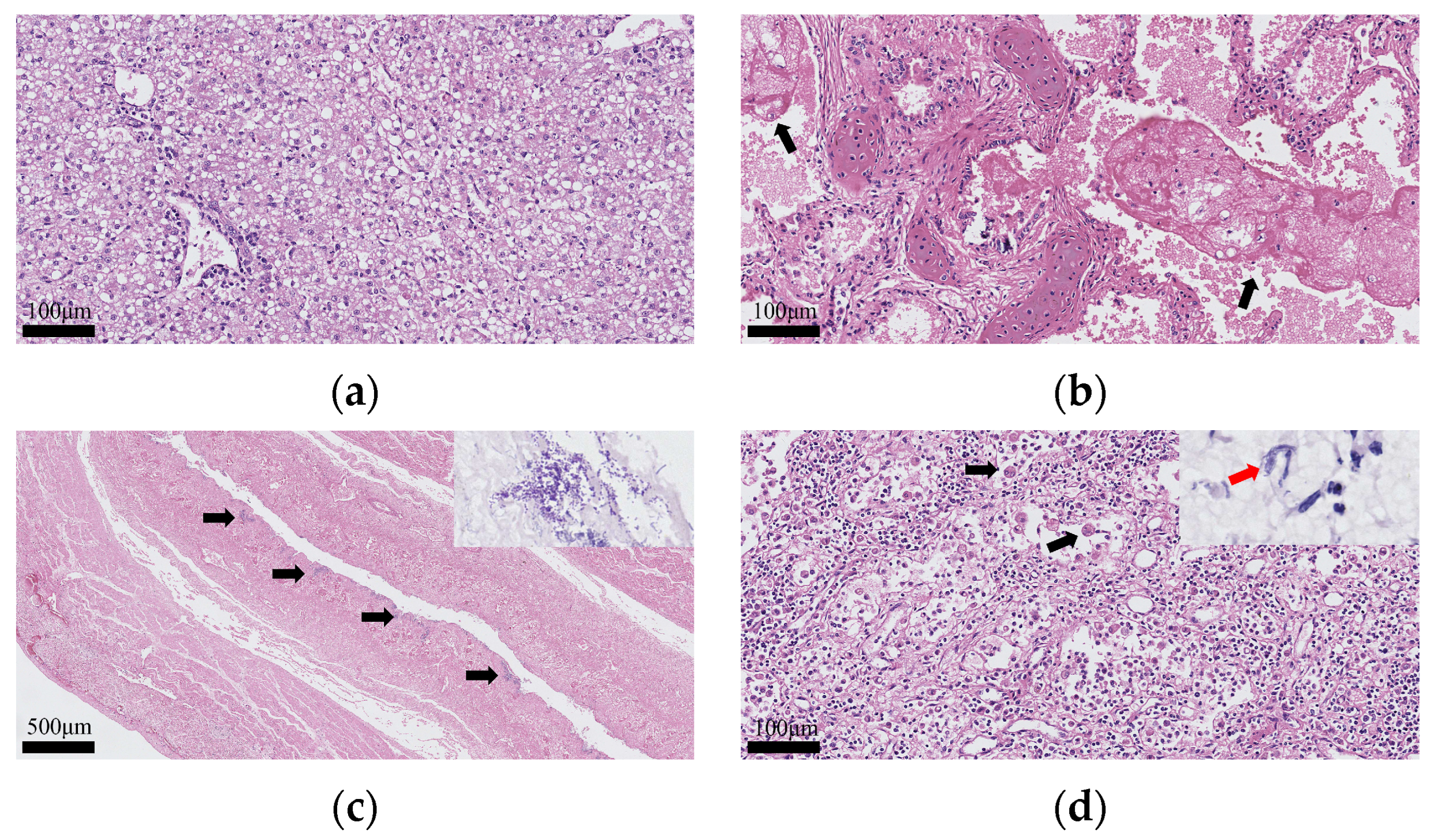

3.3. Histological and Molecular Pathology Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| LDH | Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| TBIL | Total Bilirubin |

| BUN | Blood Urea Nitrogen |

| Cr | Creatinine |

| ITS | Internal Transcribed Spacer |

| PAS | Periodic Acid–Schiff |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| FFPE | Formalin-Fixed-Paraffin-Embedded |

References

- Grattarola, C.; Pietroluongo, G.; Belluscio, D.; Berio, E.; Canonico, C.; Centelleghe, C.; Cocumelli, C.; Crotti, S.; Denurra, D.; Di Donato, A.; et al. Pathogen Prevalence in Cetaceans Stranded along the Italian Coastline between 2015 and 2020. Pathogens 2024, 13, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamio, T.; Nojo, H.; Kano, R.; Murakami, M.; Odani, Y.; Kanda, K.; Mori, T.; Akune, Y.; Kurita, M.; Okada, A.; et al. Successful Treatment of Fungal Dermatitis in a Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus). Microorganisms 2025, 13, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Bustos, V.; Rosario Medina, I.; Cabañero Navalón, M.D.; Ruiz Gaitán, A.C.; Pemán, J.; Acosta-Hernández, B. Candida spp. in Cetaceans: Neglected Emerging Challenges in Marine Ecosystems. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balik, S.E.; Ossiboff, R.J.; Stacy, N.I.; Wellehan, J.F.X.; Huguet, E.E.; Gallastegui, A.; Childress, A.L.; Baldrica, B.E.; Dolan, B.A.; Adler, L.E.; et al. Case report: Sarcocystis speeri, Aspergillus fumigatus, and novel Treponema sp. infections in an adult Atlantic spotted dolphin (Stenella frontalis). Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1132161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, R. Bacteria and fungi of marine mammals: A review. Can. Vet. J. 2000, 41, 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Bustos, V.; Rosario Medina, I.; Cabanero-Navalon, M.D.; Williams, R.S.; Macgregor, S.K.; John, S.K.; Aznar, F.J.; Gozalbes, P.; Acosta-Hernández, B. Aspergillus Infections in Cetaceans: A Systematic Review of Clinical, Ecological, and Conservation Perspectives. Biology 2025, 14, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Shi, J.; Lu, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Wei, J.; Zhao, K.; Gao, F.; He, W. Benign mixed mammary tumor with sebaceous differentiation in a dog. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2024, 86, 684–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J.; Innis, M.; Gelfand, D.; Sninsky, J. Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols; Academic Press Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; Volume 31, pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakeeb, S.; Targowski, S.P.; Spotte, S. Chronic cutaneous candidiasis in bottle-nosed dolphins. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1977, 171, 961–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, J.L.; Buck, J.; Spotte, S. Candidiasis in captive cetaceans. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1983, 181, 1316–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordes, D.O. Dolphins and their diseases. N. Z. Vet. J. 1982, 30, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Cladosporium spp. (Cladosporiaceae) isolated from Eucommia ulmoides in China. MycoKeys 2022, 91, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.B.; Chen, P.; Sun, T.T.; Wang, X.J.; Li, D.M. Acne-Like Subcutaneous Phaeohyphomycosis Caused by Cladosporium cladosporioides: A Rare Case Report and Review of Published Literatures. Mycopathologia 2016, 181, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, O.S.; D’Elia, M.P.B.; Santos, S.S.D.; Ricci, G. Phaeohyphomycosis caused by Cladosporium cladosporioides: Importance of molecular identification in challenging cases. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2025, 100, 501196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, M.H.; Park, M.S.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, T.I.; Kim, H.G. Cladosporium cladosporioides and C. tenuissimum Cause Blossom Blight in Strawberry in Korea. Mycobiology 2015, 43, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, C.; Muniz, M.F.; Rolim, J.M.; Martins, R.R.; Rosenthal, V.C.; Maciel, C.G.; Mezzomo, R.; Reiniger, L.R. Morphological and molecular characterization of Cladosporium cladosporioides species complex causing pecan tree leaf spot. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016, 15, 8714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, T.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, X.; Wang, J. First Report of Ear Rot of Chenopodium quinoa Caused by Cladosporium cladosporioides in Shanxi, China. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domiciano, I.G.; Domit, C.; Trigo, C.C.; de Alcântara, B.K.; Headley, S.A.; Bracarense, A.P. Phaeohyphomycoses in a free-ranging loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) from Southern Brazil. Mycopathologia 2014, 178, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spano, M.; Zuliani, D.; Peano, A.; Bertazzolo, W. Cladosporium cladosporioides-complex infection in a mixed-breed dog. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2018, 47, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velázquez-Jiménez, Y.; Hernández-Castro, R.; Romero-Romero, L.; Salas-Garrido, C.G.; Martínez-Chavarría, L.C. Feline Phaeohyphomycotic Cerebellitis Caused by Cladosporium cladosporioides-complex: Case Report and Review of Literature. J. Comp. Pathol. 2019, 170, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haligur, M.; Ozmen, O.; Dorrestein, G.M. Fatal systemic cladosporiosis in a merino sheep flock. Mycopathologia 2010, 170, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poutahidis, T.; Angelopoulou, K.; Karamanavi, E.; Polizopoulou, Z.S.; Doulberis, M.; Latsari, M.; Kaldrymidou, E. Mycotic encephalitis and nephritis in a dog due to infection with Cladosporium cladosporioides. J. Comp. Pathol. 2009, 140, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Gu, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, D.; Ling, S.; Hou, J.; Wang, C.; Cao, S.; Huang, X.; Wen, X.; et al. Phaeohyphomycotic dermatitis in a giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) caused by Cladosporium cladosporioides. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2013, 2, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.R.; Milheiro, A.; Pacheco, F.A. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Cladosporium cladosporioides. Med. Mycol. 2001, 39, 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajello, L. Hyalohyphomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis: Two global disease entities of public health importance. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1986, 2, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenburg, L.S.; Snider, T.A.; Wilson, A.; Confer, A.W.; Ramachandran, A.; Mani, R.; Rizzi, T.; Nafe, L. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis in a dog. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2017, 15, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávalos-Téllez, R.; Suárez-Güemes, F.; Carrillo Casas, E.M.; Hernández-Castro, R. Bacteria and yeast normal microbiota from respiratory tract and genital area of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). In Current Research, Technology and Education Topics in Applied Microbiology and Microbial Biotechnology; Formatex Research Center: Norristown, PA, USA, 2010; pp. 666–673. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.; Du, T.; Ma, X.; Li, J. Investigating the effect of nitrate on juvenile turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) growth performance, health status, and endocrine function in marine recirculation aquaculture systems. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 208, 111617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, J.A.; Alonso, A.; Salamanca, A. Nitrate toxicity to aquatic animals: A review with new data for freshwater invertebrates. Chemosphere 2005, 58, 1255–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bressem, M.F.; Duignan, P.J.; Banyard, A.; Barbieri, M.; Colegrove, K.M.; De Guise, S.; Di Guardo, G.; Dobson, A.; Domingo, M.; Fauquier, D.; et al. Cetacean morbillivirus: Current knowledge and future directions. Viruses 2014, 6, 5145–5181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bressem, M.F.; Van Waerebeek, K.; Duignan, P.J. Tattoo Skin Disease in Cetacea: A Review, with New Cases for the Northeast Pacific. Animals 2022, 12, 3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangredi, B.P.; Medway, W. Post-mortem isolation of Vibrio alginolyticus from an Atlantic white-sided dolphin (Lagenorynchus acutus). J. Wildl. Dis. 1980, 16, 329–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Renzo, L.; Di Francesco, G.; Profico, C.; Di Francesco, C.E.; Ferri, N.; Averaimo, D.; Di Guardo, G. Vibrio parahaemolyticus- and V. alginolyticus-associated meningo-encephalitis in a bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) from the Adriatic coast of Italy. Res. Vet. Sci. 2017, 115, 363–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canales, R.; Sanchez-Okrucky, R.; Bustamante, L.; Vences, M.; Dennis, M.M. Melioidosis in a Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) after a Hurricane in the Caribbean Islands. J. Zoo. Wildl. Med. 2020, 51, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, K.; Zhao, P.; Cheng, L.; Zhao, F.; Bi, L.; Li, B.; He, X.; Guo, D. Cladosporium Infection in a Captive Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus): A Rare Case Report from Quanzhou, China. Animals 2025, 15, 3607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243607

Jiang K, Zhao P, Cheng L, Zhao F, Bi L, Li B, He X, Guo D. Cladosporium Infection in a Captive Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus): A Rare Case Report from Quanzhou, China. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243607

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Kai, Pengyu Zhao, Lin Cheng, Feiyu Zhao, Lan Bi, Bao Li, Xianjing He, and Donghua Guo. 2025. "Cladosporium Infection in a Captive Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus): A Rare Case Report from Quanzhou, China" Animals 15, no. 24: 3607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243607

APA StyleJiang, K., Zhao, P., Cheng, L., Zhao, F., Bi, L., Li, B., He, X., & Guo, D. (2025). Cladosporium Infection in a Captive Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus): A Rare Case Report from Quanzhou, China. Animals, 15(24), 3607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243607