CircRNA_01754 Regulates Milk Fat Production Through the Hippo Signaling Pathway

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

2.2. Collection of Breast Tissue Samples

2.3. RNA Extraction and Sequencing Analysis

2.4. Cell Culture

2.5. Plasmid Construction and Cell Transfection

2.6. Real Time Fluorescence Quantification

2.7. Western Blot

2.8. Determination of Triglyceride Content and Cholesterol

2.9. Detection of Luciferase Activity

2.10. Data Analysis

3. Results

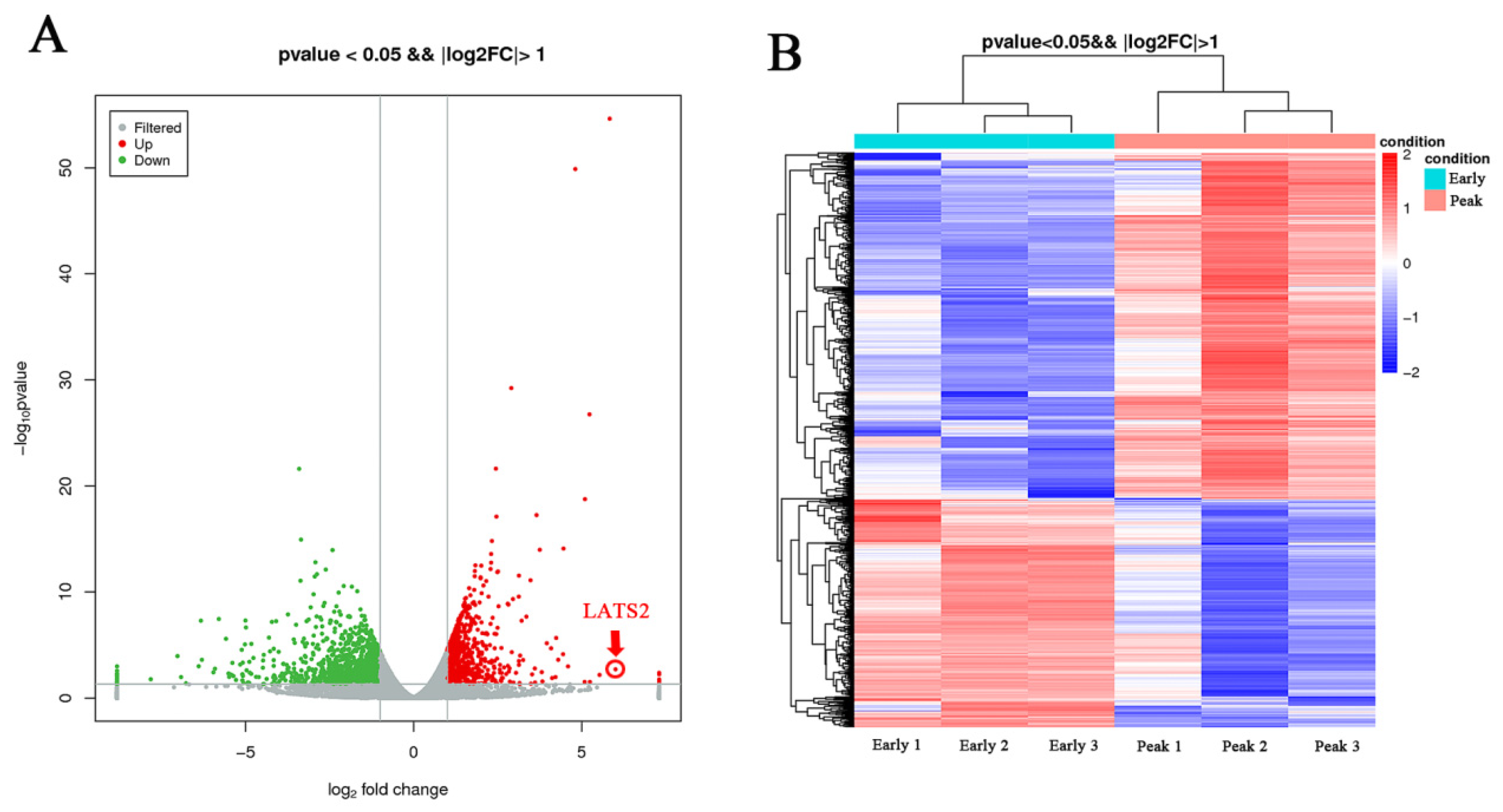

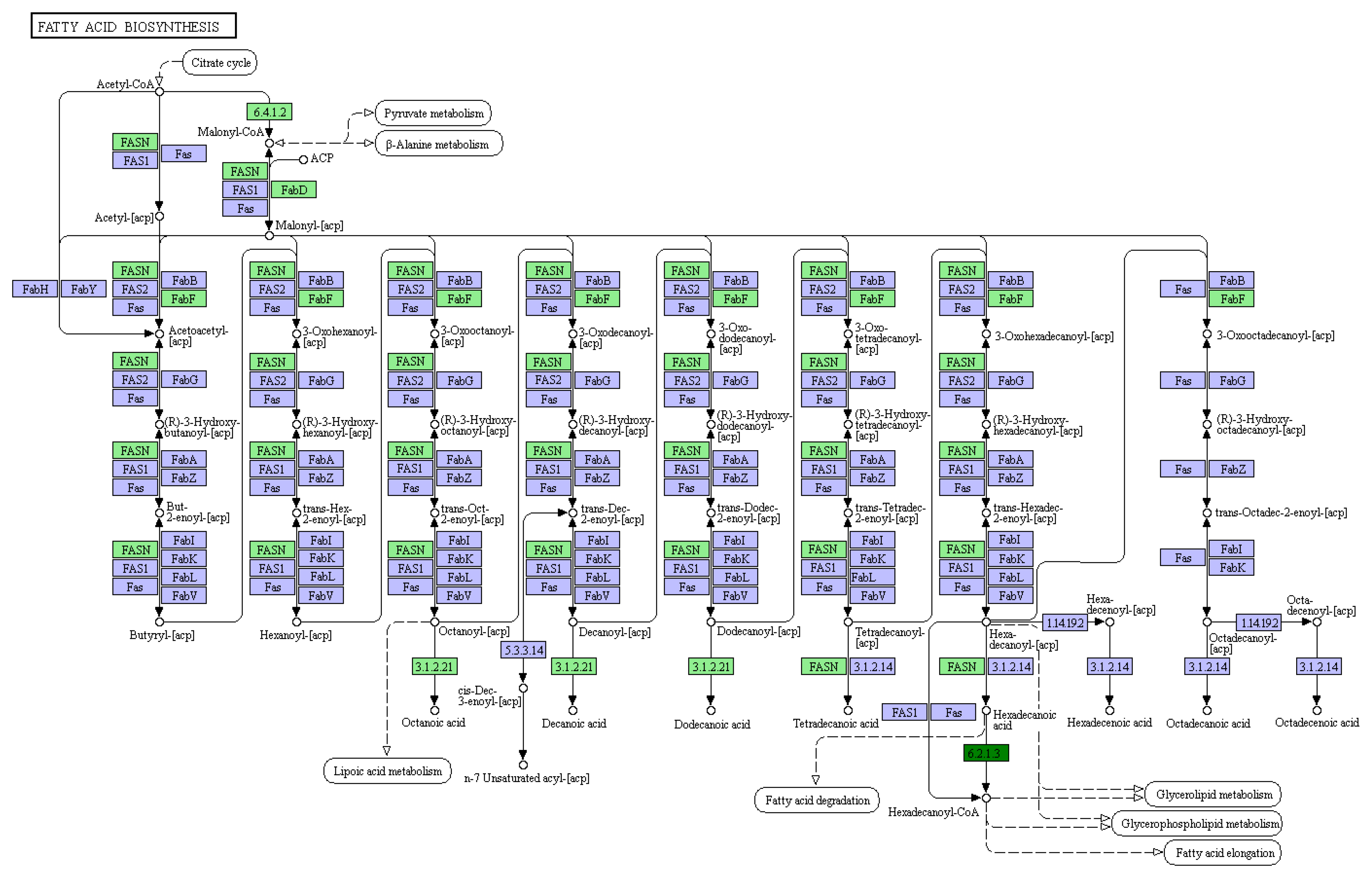

3.1. Differential Expression Gene and GO/KEGG Analysis

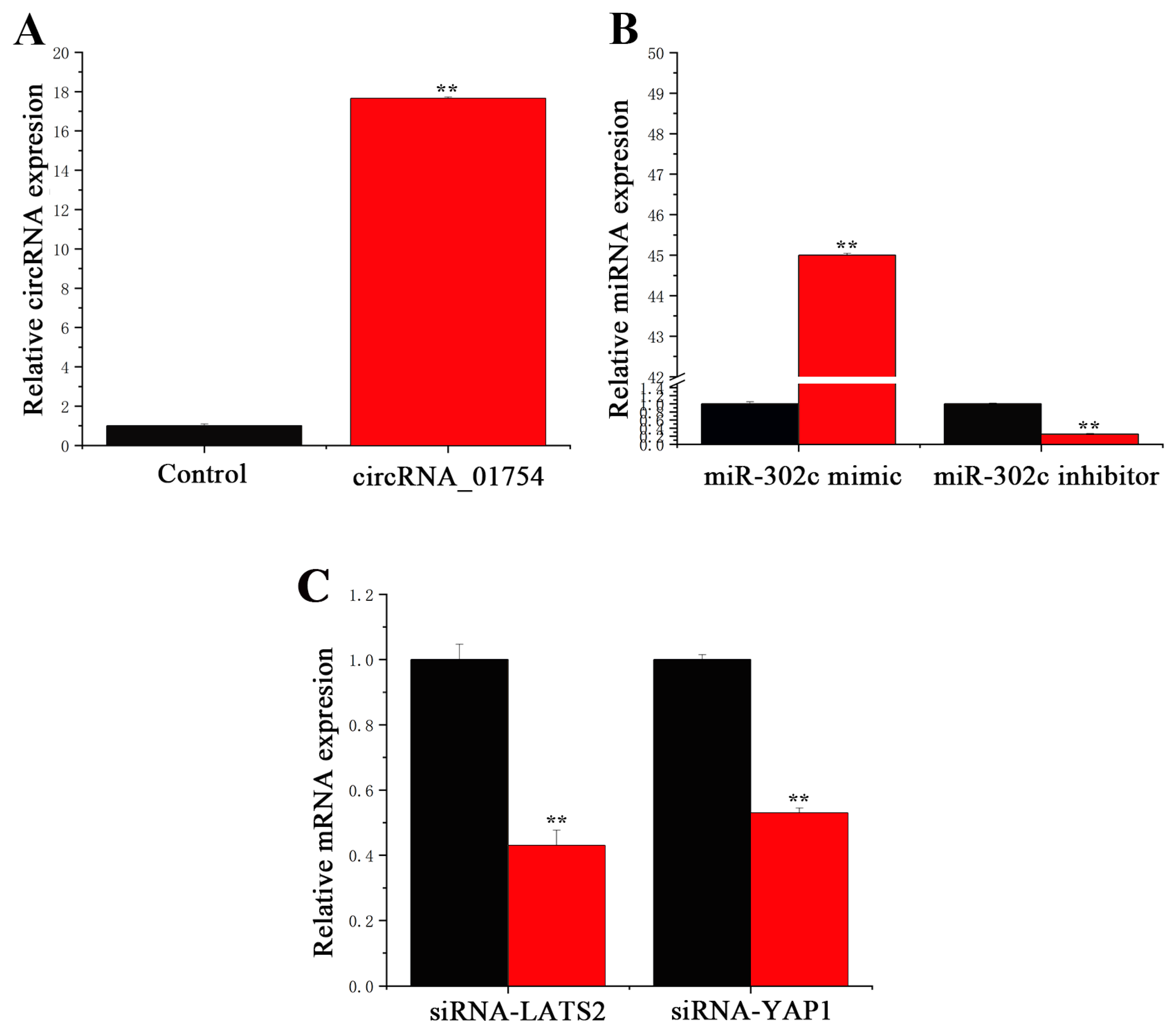

3.2. Transfection Efficiency of circRNA, miRNA, and siRNA

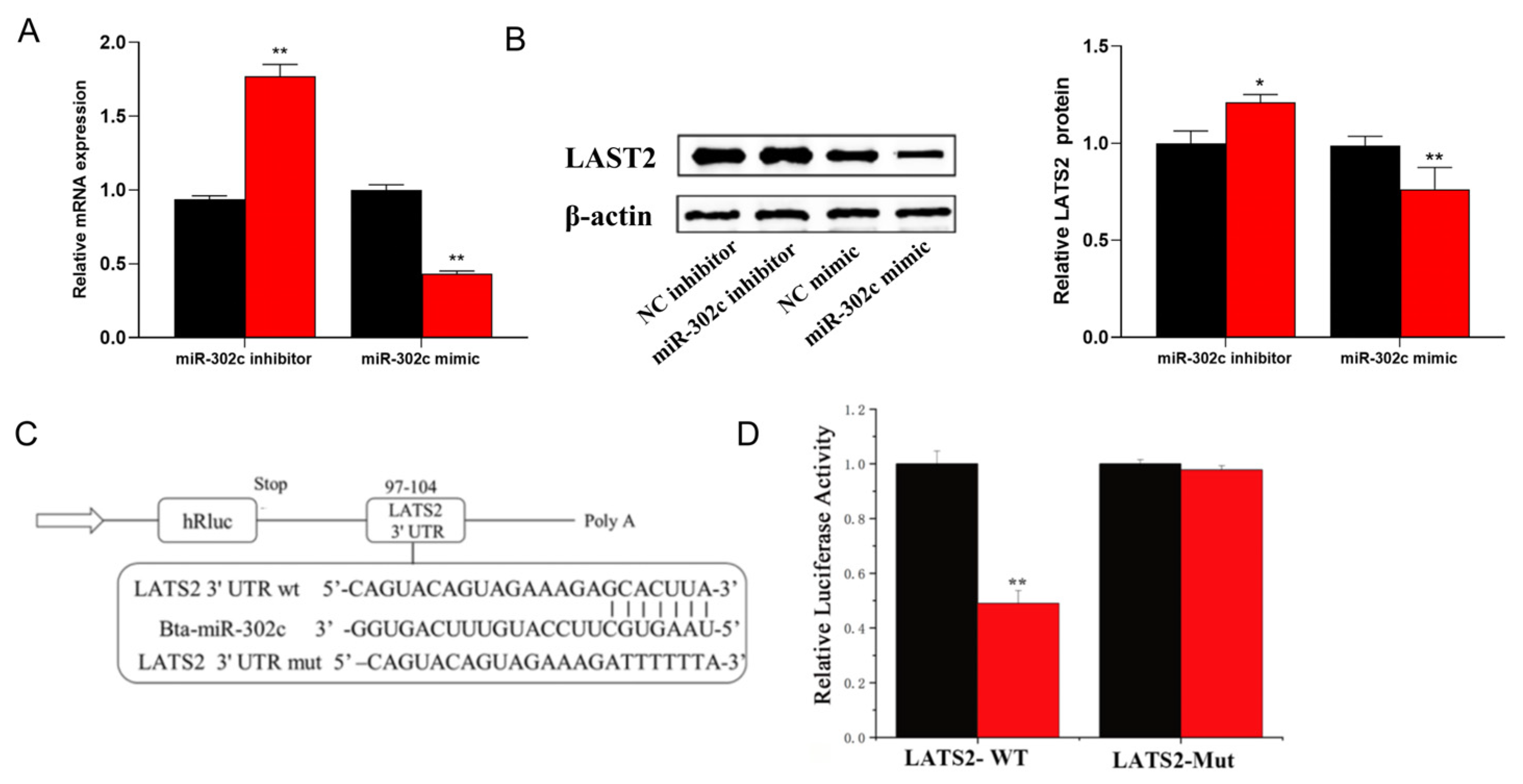

3.3. miR-302c Specific Targeting of LATS2

3.4. circRNA_01754 Regulates LATS2 Expression Through Competitive Binding to miR-302c in BMECs

3.5. Functions of circRNA_01754 and miR-302c in BMECs

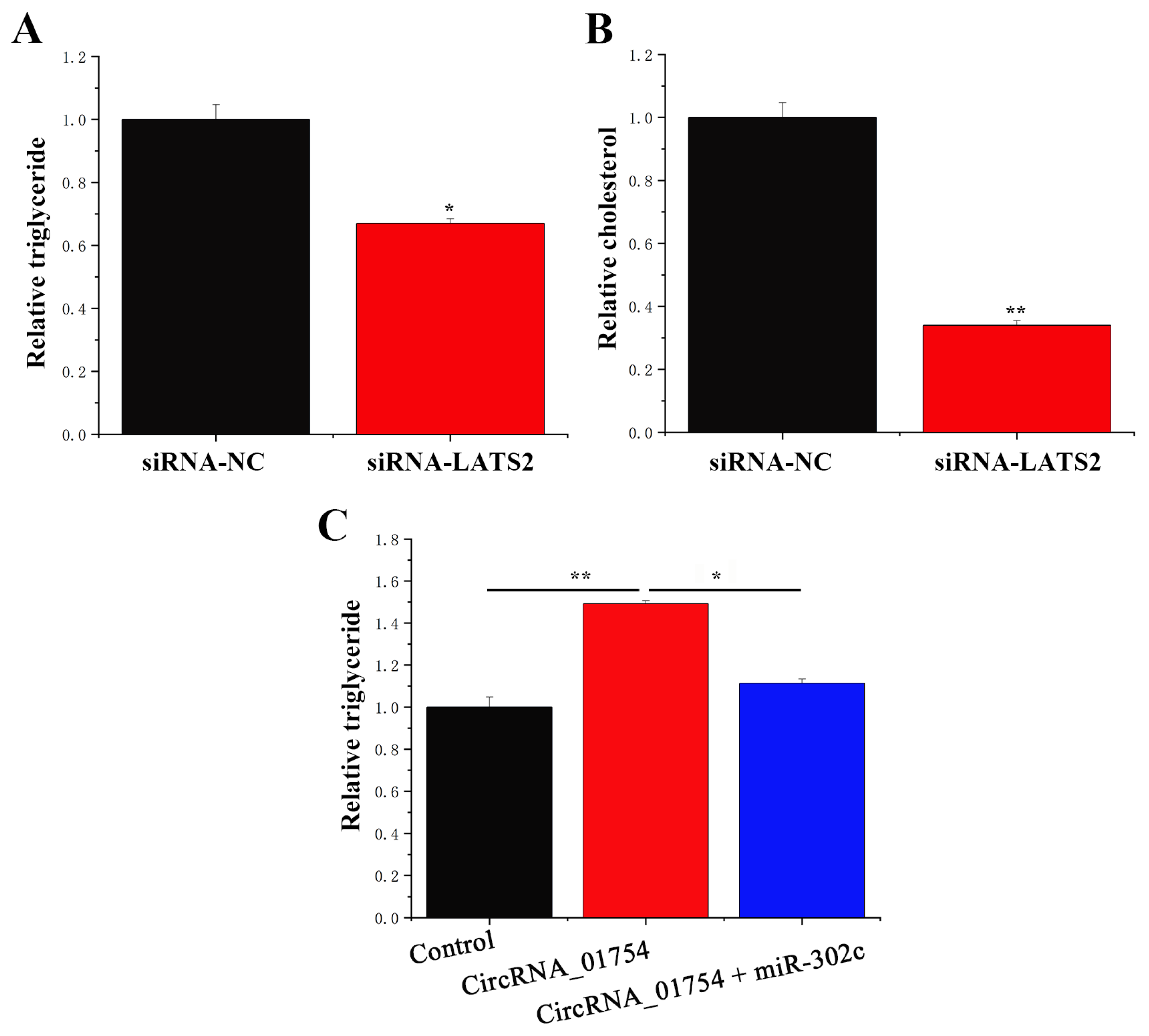

3.6. circRNA_01754 Can Regulate Intracellular Triglyceride Content by Adsorbing miR-302c in BMECs After siRNA-LATS2 Treatment

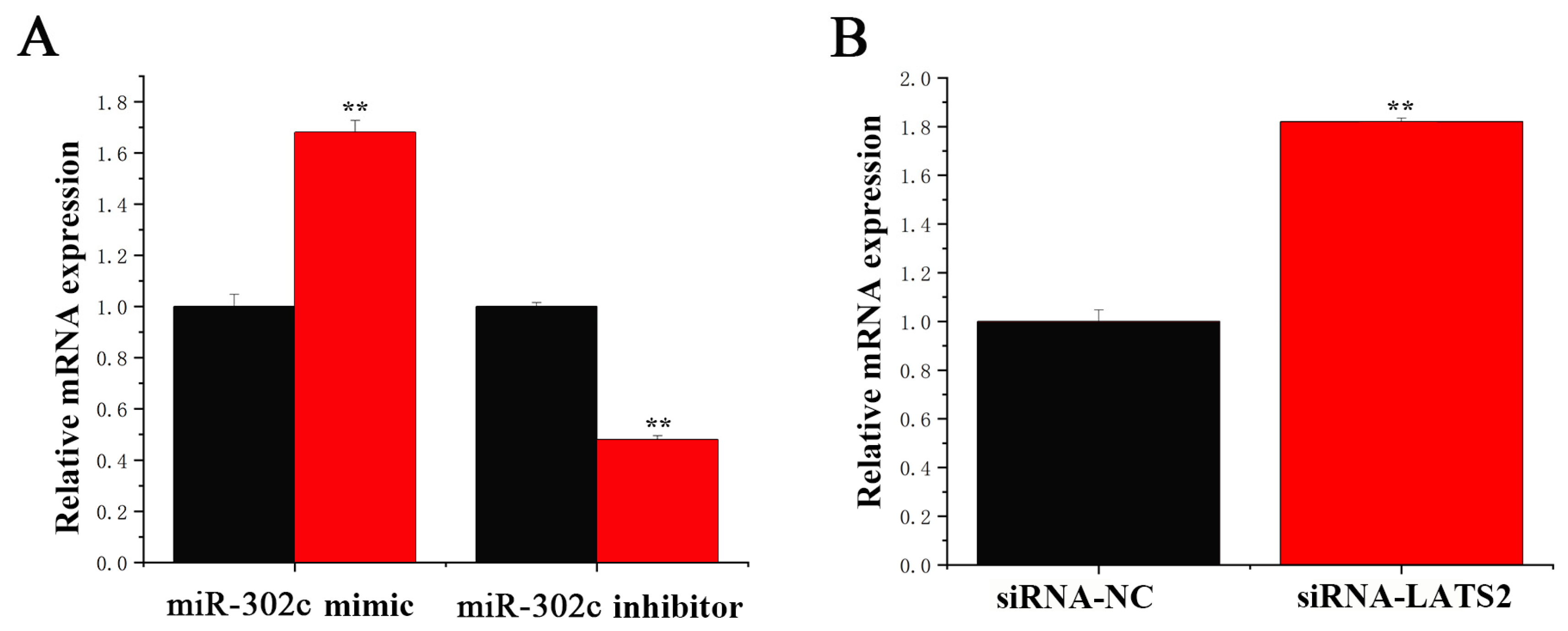

3.7. miR-302c and LATS2 Synergistically Regulate YAP1

4. Discussion

4.1. miRNA in Animal Mammary Gland Research

4.2. Hippo Signaling Pathway Affects Milk Fat Metabolism in Dairy Cows

4.3. circRNA_01754 Regulates Milk Fat Metabolism in Dairy Cows’ Mammary Glands

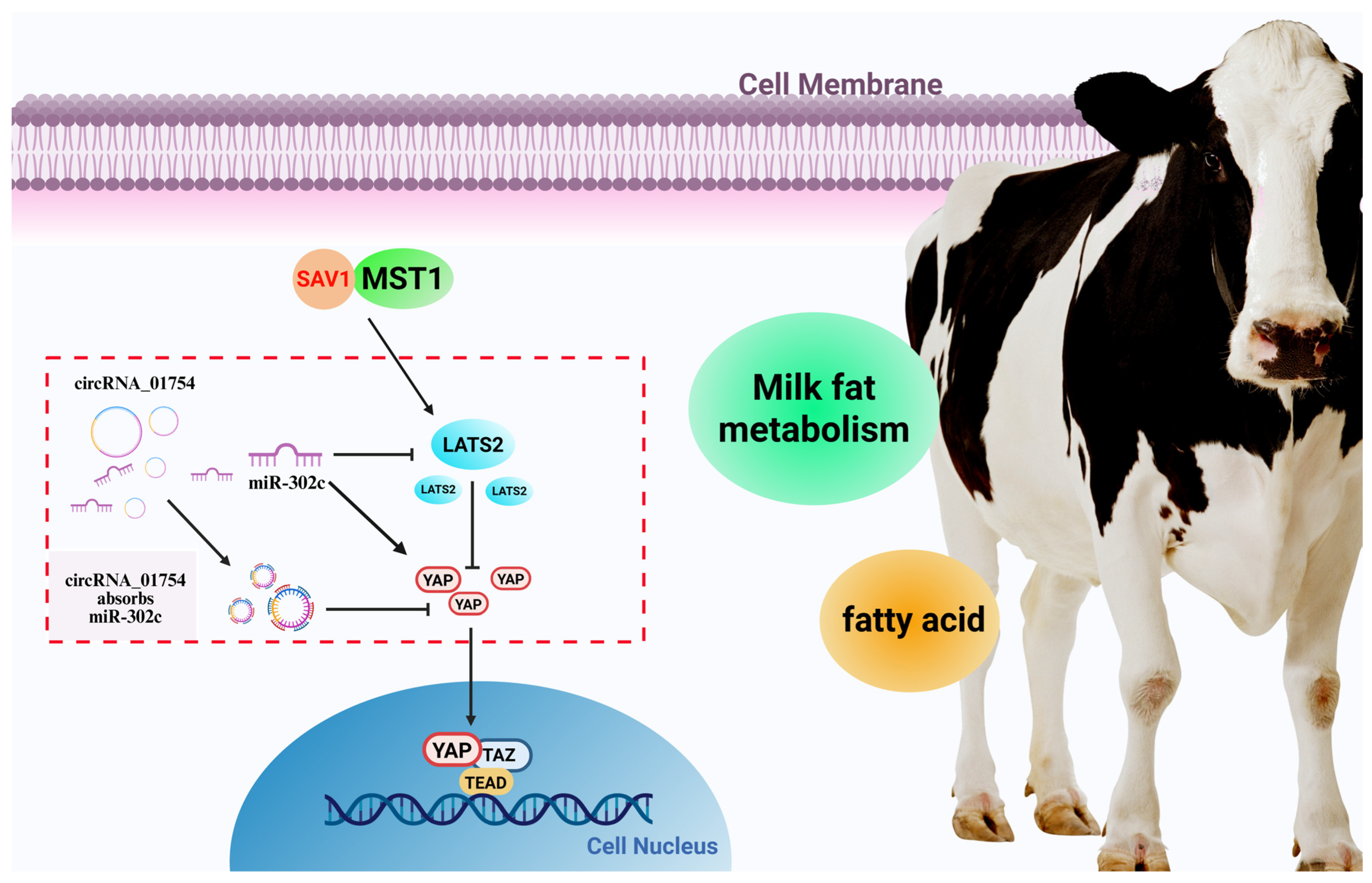

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome. Nature 2004, 431, 931–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Zhang, Z.; Krause, H.M. Long Noncoding RNAs and Repetitive Elements: Junk or Intimate Evolutionary Partners? Trends Genet. 2019, 35, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, J.C.; Adams, M.D.; Myers, E.W.; Li, P.W.; Mural, R.J.; Sutton, G.G.; Smith, H.O.; Yandell, M.; Evans, C.A.; Holt, R.A.; et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science 2001, 291, 1304–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, S.; Adams, J.C. Physiological roles of non-coding RNAs. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2019, 317, C1–C2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Pupwe, G.; Takehiro, K.; Yu, G.; Zhan, M.; Xu, B. The function and mechanisms of action of non-coding RNAs in prostatic diseases. Cell Investig. 2025, 1, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Cappello, T.; Wang, L. Emerging role of microRNAs in lipid metabolism. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2015, 5, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacazette, É.; Diallo, L.H.; Tatin, F.; Garmy-Susini, B.; Prats, A.C. Do circular RNAs play tricks on us? Med. Sci. 2020, 36, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, T.; Wang, X.; He, A. Circles reshaping the RNA world: From waste to treasure. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, B.; Li, C.; Dong, D.; Lan, X.; Huang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Lin, F.; Zhao, X.; et al. miR-378a-3p promotes differentiation and inhibits proliferation of myoblasts by targeting HDAC4 in skeletal muscle development. RNA Biol. 2016, 13, 1300–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golovina, E.; Eaton, C.; Cox, V.; Andel, J.; Savvulidi Vargova, K. Mechanism of Action of circRNA/miRNA Network in DLBCL. Noncoding RNA 2025, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justice, R.W.; Zilian, O.; Woods, D.F.; Noll, M.; Bryant, P.J. The Drosophila tumor suppressor gene warts encodes a homolog of human myotonic dystrophy kinase and is required for the control of cell shape and proliferation. Genes Dev. 1995, 9, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Tumaneng, K.; Guan, K.-L. The Hippo pathway in organ size control, tissue regeneration and stem cell self-renewal. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylon, Y.; Gershoni, A.; Rotkopf, R.; Biton, I.E.; Porat, Z.; Koh, A.P.; Sun, X.; Lee, Y.; Fiel, M.-I.; Hoshida, Y.; et al. The LATS2 tumor suppressor inhibits SREBP and suppresses hepatic cholesterol accumulation. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, F.; Wu, Z.; Zou, F.; Wang, S.; Wang, X. The Hippo-YAP/TAZ Signaling Pathway in Intestinal Self-Renewal and Regeneration After Injury. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 894737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, F.; Jin, Z.; Zhao, T. The Hippo Pathway and Viral Infections. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Han, M.; Li, G.; Zhang, B.; Yang, Y.; Loor, J.J.; Yang, Z.; et al. CircRNA-02191 regulating unsaturated fatty acid synthesis by adsorbing miR-145 to enhance CD36 expression in bovine mammary gland. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 244, 125306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Ke, H.; Wen, A.; Gao, B.; Shi, J.; Feng, Y. Structural basis of microRNA processing by Dicer-like 1. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 1389–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, G.; Grieco, G.E.; Brusco, N.; Ventriglia, G.; Formichi, C.; Marselli, L.; Marchetti, P.; Dotta, F. MicroRNA Expression Analysis of In Vitro Dedifferentiated Human Pancreatic Islet Cells Reveals the Activation of the Pluripotency-Related MicroRNA Cluster miR-302s. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Gan, L.; Si, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Gou, Z.; Zhang, H. Role of miR-302/367 cluster in human physiology and pathophysiology. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2020, 52, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thi, K.; Del Toro, K.; Licon-Munoz, Y.; Sayaman, R.W.; Hines, W.C. Comprehensive identification, isolation, and culture of human breast cell types. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Y.; Mao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, M. Transcriptional regulation of milk fat synthesis in dairy cattle. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 96, 105208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Mao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, C.; Chen, Z. Ubiquitination and De-Ubiquitination in the Synthesis of Cow Milk Fat: Reality and Prospects. Molecules 2024, 29, 4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Shi, H.; Sun, S.; Xu, H.; Cao, D.; Luo, J. MicroRNA-181b suppresses TAG via target IRS2 and regulating multiple genes in the Hippo pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2016, 348, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holden, J.K.; Cunningham, C.N. Targeting the Hippo Pathway and Cancer through the TEAD Family of Transcription Factors. Cancers 2018, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Luo, Y.; Yu, S.; Cui, Y.; Xu, G.; Wang, L.; Pan, Y.; He, H. Transcriptional profiling of two different physiological states of the yak mammary gland using RNA sequencing. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, J.S.; Lohakare, J.; Bionaz, M. Biosynthesis of milk fat, protein, and lactose: Roles of transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation. Physiol. Genom. 2016, 48, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chu, S.; Liang, Y.; Xu, T.; Sun, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Mao, Y.; Loor, J.J.; et al. miR-497 regulates fatty acid synthesis via LATS2 in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 8625–8636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Chen, Q.; Jia, Y.; Deng, J.; Jiang, S.; Qin, G.; Qiu, Q.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Jiang, H. Isolation, characterization, and SREBP1 functional analysis of mammary epithelial cell in buffalo. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, e12997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Chen, Q.; Tian, K.; Xia, Y.; Dong, G.; Yang, Z. Functional Role of circRNAs in the Regulation of Fetal Development, Muscle Development, and Lactation in Livestock. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 5383210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, P.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Z.; Liang, G.; Xie, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Loor, J.J. Circ003429 Regulates Unsaturated Fatty Acid Synthesis in the Dairy Goat Mammary Gland by Interacting with miR-199a-3p, Targeting the YAP1 Gene. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, H.; Hu, B.; Xie, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, J.; Chen, T.; Luo, J.; Wang, S.; Jiang, Q.; et al. Emerging Roles of Heat-Induced circRNAs Related to Lactogenesis in Lactating Sows. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Luoreng, Z.; Wang, X. Identification of potential key circular RNAs associated with Escherichia coli-infected bovine mastitis using RNA-sequencing: Preliminary study results. Vet. Res. Commun. 2024, 49, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Cai, Z.; Mu, T.; Yu, B.; Wang, Y.; Ma, R.; Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Gu, Y. CircRNA screening and ceRNA network construction for milk fat metabolism in dairy cows. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 995629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Liu, J.; Fang, X.; Chen, H. Circular RNA of cattle casein genes are highly expressed in bovine mammary gland. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 4750–4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Zhou, J.; Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Loor, J.J.; Liang, Y.; Wu, H.; Yang, Z. Circ09863 Regulates Unsaturated Fatty Acid Metabolism by Adsorbing miR-27a-3p in Bovine Mammary Epithelial Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 8589–8601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Z.; Zhou, H.; Hickford, J.G.H.; Gong, H.; Wang, J.; Hu, J.; Liu, X.; Li, S.; Zhao, M.; Luo, Y. Identification and characterization of circular RNA in lactating mammary glands from two breeds of sheep with different milk production profiles using RNA-Seq. Genomics 2020, 112, 2186–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Chen, J.; Gao, R.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z. CircRNA_01754 Regulates Milk Fat Production Through the Hippo Signaling Pathway. Animals 2025, 15, 3606. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243606

Li X, Chen J, Gao R, Feng Y, Zhang Z, Chen Z. CircRNA_01754 Regulates Milk Fat Production Through the Hippo Signaling Pathway. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3606. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243606

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiaofen, Jiahao Chen, Rui Gao, Ye Feng, Zhifeng Zhang, and Zhi Chen. 2025. "CircRNA_01754 Regulates Milk Fat Production Through the Hippo Signaling Pathway" Animals 15, no. 24: 3606. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243606

APA StyleLi, X., Chen, J., Gao, R., Feng, Y., Zhang, Z., & Chen, Z. (2025). CircRNA_01754 Regulates Milk Fat Production Through the Hippo Signaling Pathway. Animals, 15(24), 3606. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243606