Dietary Pineapple Pomace Complex Improves Growth Performance and Reduces Fecal Odor in Weaned Piglets by Modulating Fecal Microbiota, SCFAs, and Indoles

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals, Diet and Experimental Design

2.2. Growth Performance Assessment and Fecal Sample Collection and Processing

2.3. 16S rRNA Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

2.4. Analysis of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Feces

2.5. Analysis of Indoleacetic Acid and Skatole in Feces

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Effects of PPC on Growth Performance of Weaned Piglets Growth Performance

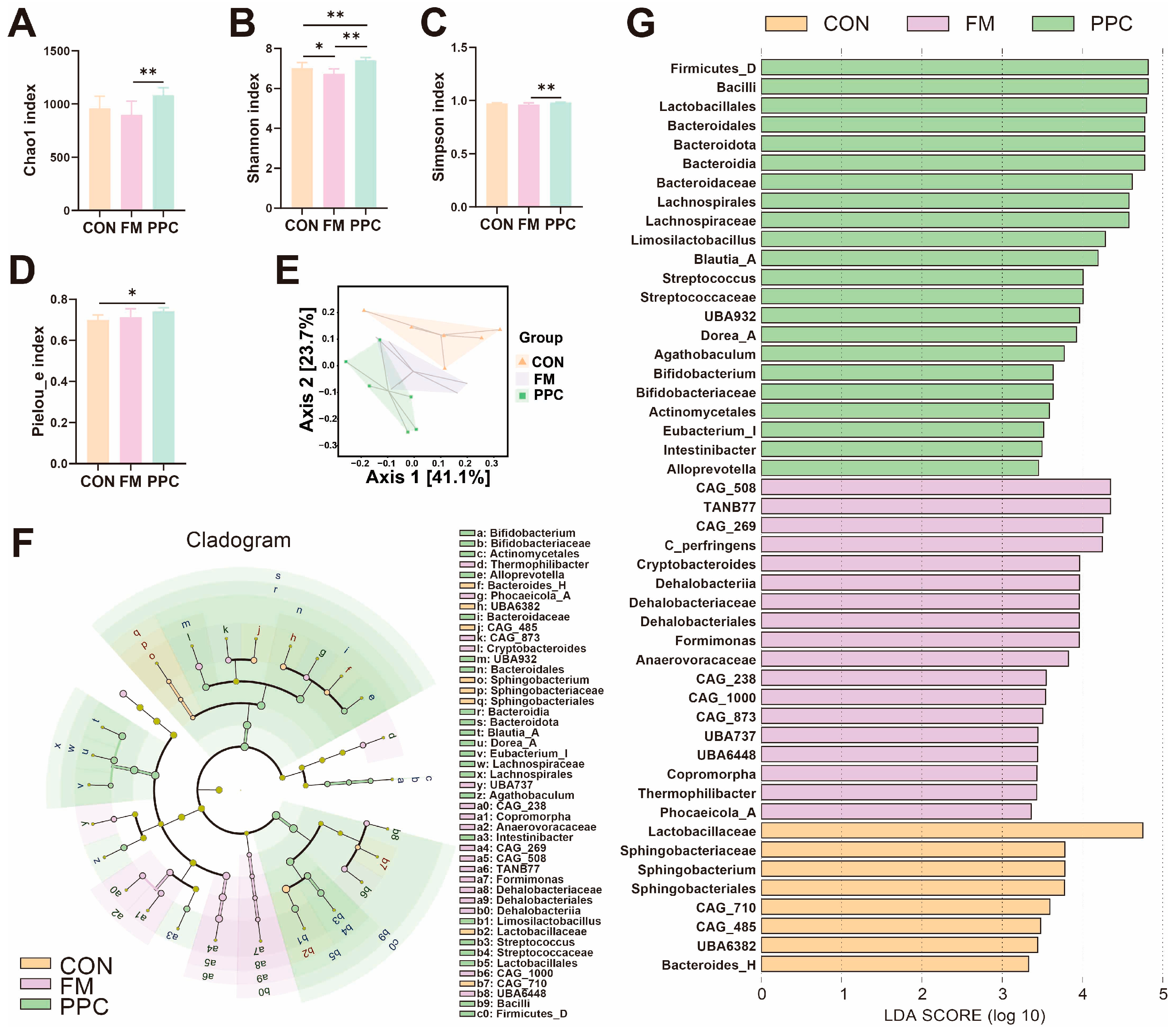

3.2. The Effects of PPC on the Fecal Microbiota Characterization of Weaned Piglets Fecal Microbiota Community Characerization

3.3. The Effects of PPC on SCFAs in Weaned Piglets SCFA Characerization and Correlation Analysis

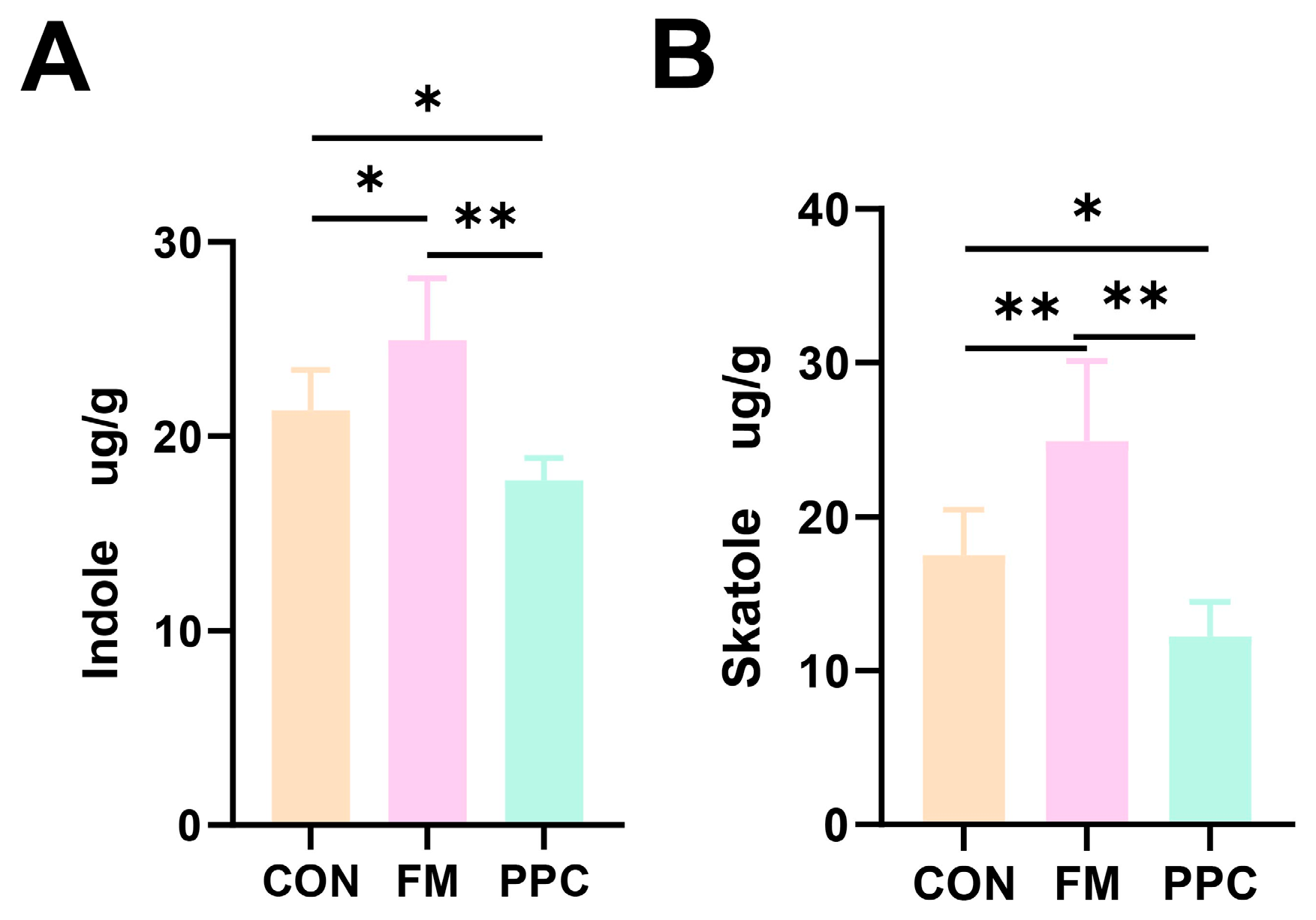

3.4. Fecal Odorous Compounds Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. The Effects of PPC on Growth Performance of Weaned Piglets

4.2. The Effects of PPC on the Fecal Microbiota Characterization of Weaned Piglets

4.3. The Effects of PPC on SCFAs in Weaned Piglets

4.4. Effects of PPC on Fecal Odor Compound and Indole Levels in Weaned Piglets

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nath, P.C.; Ojha, A.; Debnath, S.; Neetu, K.; Bardhan, S.; Mitra, P.; Sharma, M.; Sridhar, K.; Nayak, P.K. Recent Advances in Valorization of Pineapple (Ananas comosus) Processing Waste and by-Products: A Step towards Circular Bioeconomy. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 136, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Singh, B. Pineapple By-Products Utilization: Progress towards the Circular Economy. Food Humanit. 2024, 2, 100243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves Nobre, T.; de Sousa, A.A.; Pereira, I.C.; Carvalho Pedrosa-Santos, Á.M.; Lopes, L.D.O.; Debia, N.; El-Nashar, H.A.; El-Shazly, M.; Islam, M.T.; Castro e Sousa, J.M.D.; et al. Bromelain as a natural anti-inflammatory drug: A systematic review. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 39, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jose, M.; Himashree, P.; Sengar, A.S.; Sunil, C.K. Valorization of food industry by-product (pineapple pomace): A study to evaluate its effect on physicochemical and textural properties of developed cookies. Meas. Food 2022, 6, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadidi, M.; Ibarz, A.; Khaksar, F.B.; Hasiri, Z. Polysaccharides from pineapple core as a canning by-product: Extraction optimization, chemical structure, antioxidant and functional properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 163, 2357–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Li, S.; Diao, H.; Huang, C.; Yan, J.; Wei, X.; Zhou, M.; He, P.; Wang, T.; Fu, H.; et al. The Interaction between Dietary Fiber and Gut Microbiota, and Its Effect on Pig Intestinal Health. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1095740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, W.; Zhu, X.; Sun, X.; Xiao, J.; Li, D.; Cui, Y.; Wang, C.; Shi, Y. Response of Gut Microbiota to Dietary Fiber and Metabolic Interaction with SCFAs in Piglets. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selani, M.M.; Brazaca, S.G.C.; Dos Santos Dias, C.T.; Ratnayake, W.S.; Flores, R.A.; Bianchini, A. Characterisation and Potential Application of Pineapple Pomace in an Extruded Product for Fibre Enhancement. Food Chem. 2014, 163, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (NRC). Nutrient Requirements of Swine: Eleventh Revised Edition; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, T.S.; Thomaz, M.C.; Castelini, F.R.; Alvarenga, P.V.A.; De Oliveira, J.A.; Ramos, G.F.; Ono, R.K.; Milani, N.C.; Dos Santos Ruiz, U. Evaluation of Pineapple Byproduct at Increasing Levels in Heavy Finishing Pigs Feeding. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020, 269, 114664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Lu, Y.; Guo, X.; Zong, M.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, P.; Pang, J.; Peng, X.; Sun, Z. Multi-Omic Analysis for Dietary Supplementation of Different Ratios of Soluble and Insoluble Fiber on Intestinal Microbiota, Metabolites and Inflammation of Weaned Piglets. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, S2095311925001388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Gao, G.; Yin, C.; Bai, R.; Li, Y.; Sun, W.; Pi, Y.; Jiang, X.; Li, X. The Effects of Dietary Silybin Supplementation on the Growth Performance and Regulation of Intestinal Oxidative Injury and Microflora Dysbiosis in Weaned Piglets. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erinle, T.J.; De Oliveira, M.J.K.; Htoo, J.K.; Mendoza, S.M.; Columbus, D.A. Effect of Indigestible Dietary Protein on Growth Performance and Health Status of Weaned Pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 103, skaf372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Yin, J.; Xu, K.; Li, T.; Yin, Y. What Is the Impact of Diet on Nutritional Diarrhea Associated with Gut Microbiota in Weaning Piglets: A System Review. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 6916189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, D.A.; Coscueta, E.R.; Vilas-Boas, A.A.; Silva, S.; Teixeira, J.A.; Pastrana, L.M.; Pintado, M.M. Impact of Functional Flours from Pineapple By-Products on Human Intestinal Microbiota. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 67, 103830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzler-Zebeli, B.U.; Canibe, N.; Montagne, L.; Freire, J.; Bosi, P.; Prates, J.A.M.; Tanghe, S.; Trevisi, P. Resistant Starch Reduces Large Intestinal pH and Promotes Fecal Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria in Pigs. Animal 2019, 13, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, C.W.; Liew, M.S.; Ooi, W.; Jamil, H.; Lim, A.; Hooi, S.L.; Tay, C.S.C.; Tan, G. Effect of Green Banana and Pineapple Fibre Powder Consumption on Host Gut Microbiome. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1437645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Tang, C.; Zhang, J.; Qin, Y. Fermented Soy and Fish Protein Dietary Sources Shape Ileal and Colonic Microbiota, Improving Nutrient Digestibility and Host Health in a Piglet Model. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 911500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; He, J.; Ji, X.; Zheng, W.; Yao, W. A Moderate Reduction of Dietary Crude Protein Provide Comparable Growth Performance and Improve Metabolism via Changing Intestinal Microbiota in Sushan Nursery Pigs. Animals 2021, 11, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, P.; Wu, Y.; Guo, P.; Liu, L.; Ma, N.; Levesque, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, J.; et al. Dietary Fiber Increases Butyrate-Producing Bacteria and Improves the Growth Performance of Weaned Piglets. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 7995–8004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Huang, J.; Chen, W.; Zhao, A.; Pan, J.; Yu, F. The Influence of Increasing Roughage Content in the Diet on the Growth Performance and Intestinal Flora of Jinwu and Duroc × Landrace × Yorkshire Pigs. Animals 2024, 14, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Wang, B.; Wang, M.; Tang, R.; Xu, W.; Xiao, W. L-Theanine Alleviates Ulcerative Colitis by Repairing the Intestinal Barrier through Regulating the Gut Microbiota and Associated Short-Chain Fatty Acids. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2025, 202, 115497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Ma, Y.; Ding, S.; Fang, J.; Liu, G. Regulation of Dietary Fiber on Intestinal Microorganisms and Its Effects on Animal Health. Anim. Nutr. 2023, 14, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsan, C.F.; Ávila, P.F.; Masarin, F.; Lopes, P.R.M.; Brienzo, M. Cellooligosaccharides and Xylooligosaccharides: Production Processes, Potential Prebiotics, and Metabolism Routes by Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium. Food Res. Int. 2025, 222, 117661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; Cai, J.; Zhou, L.; Xing, L.; Zhang, W. Dietary Oxidized Beef Protein Alters Gut Microbiota and Induces Colonic Inflammatory Damage in C57BL/6 Mice. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 980204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Deng, D.; Ma, X.; Yu, M.; Lu, Y.; Song, M.; Jiang, Q. Advances in Production and invitro Degradation of Skatole in Livestock and Poultry. Chin. J. Anim. Sci. Vet. Med. 2025, 52, 2650–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Mu, C.; Zhang, C.; Yu, M.; Tian, Z.; Deng, D.; Ma, X. Magnolol-Driven Microbiota Modulation Elicits Changes in Tryptophan Metabolism Resulting in Reduced Skatole Formation in Pigs. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 467, 133423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, G.; Liu, H. Research Progress on Production Mechanism and Emission Reduction of Skatole in Livestock and Poultry. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 33, 1240–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jensen, B.B.; Canibe, N. The Mode of Action of Chicory Roots on Skatole Production in Entire Male Pigs Is Neither via Reducing the Population of Skatole-Producing Bacteria nor via Increased Butyrate Production in the Hindgut. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e02327-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjana; Tiwari, S.K. Bacteriocin-Producing Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria in Controlling Dysbiosis of the Gut Microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 851140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ji, H.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Chen, M.; Liu, H. Lactobacillus-Driven Feed Fermentation Regulates Microbiota Metabolism and Reduces Odor Emission from the Feces of Pigs. mSystems 2023, 8, e0098823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Tang, J.; Wang, L.; Yang, X.; Jiang, Z. Fermented Corn–Soybean Meal Improved Growth Performance and Reduced Diarrhea Incidence by Modulating Intestinal Barrier Function and Gut Microbiota in Weaned Piglets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Zhang, N.; Wang, J.; Cao, Y.; Johnston, L.J.; Ma, Y. Effects of Medium- and Short-Chain Fatty Acids on Growth Performance, Nutrient Digestibility, Gut Microbiota and Immune Function in Weaned Piglets. Animals 2025, 15, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Project | CON | FM | PPC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ingredient, % | |||

| Corn | 61.00 | 59.00 | 59.50 |

| Soybean Meal | 12.00 | 9.80 | 10.10 |

| Expanded Soybeans | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 |

| Fish Meal | 4.00 | 6.00 | 4.00 |

| Soybean Oil | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| Whey Powder | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| Salt | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 |

| Limestone Powder | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| Dicalcium Phosphate | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Lysine Hydrochloride | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| Methionine | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Threonine | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Premix 1 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 |

| Pineapple Pomace Complex | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 |

| Corn Starch | 0.00 | 2.20 | 1.40 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Nutritional Level | |||

| Dry Matter, % | 88.64 | 88.28 | 87.87 |

| Digestible Energy, MJ/kg | 14.21 | 14.35 | 14.18 |

| Crude Fiber, % | 3.18 | 3.74 | 3.88 |

| Crude Protein, % | 18.33 | 20.05 | 18.52 |

| Item 1 | CON | FM | PPC | SEM 2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BW of day 1 (kg) | 5.35 | 5.35 | 5.34 | 0.09 | 0.799 |

| BW of day 21 (kg) | 10.52 | 10.81 | 10.83 | 0.12 | 0.574 |

| ADG (g/d) | 247 b | 257 ab | 261 a | 2.67 | 0.046 |

| ADFI (g/d) | 340 | 343 | 349 | 2.05 | 0.156 |

| FCR | 1.38 a | 1.35 ab | 1.34 b | 0.01 | 0.032 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, S.; Jin, J.; Zheng, M.; Yin, F.; Liu, W.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y. Dietary Pineapple Pomace Complex Improves Growth Performance and Reduces Fecal Odor in Weaned Piglets by Modulating Fecal Microbiota, SCFAs, and Indoles. Animals 2025, 15, 3600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243600

Yu S, Jin J, Zheng M, Yin F, Liu W, Zhao Z, Wang L, Chen Y. Dietary Pineapple Pomace Complex Improves Growth Performance and Reduces Fecal Odor in Weaned Piglets by Modulating Fecal Microbiota, SCFAs, and Indoles. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243600

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Shengnan, Jiahao Jin, Minglin Zheng, Fuquan Yin, Wenchao Liu, Zhihui Zhao, Liyuan Wang, and Yuxia Chen. 2025. "Dietary Pineapple Pomace Complex Improves Growth Performance and Reduces Fecal Odor in Weaned Piglets by Modulating Fecal Microbiota, SCFAs, and Indoles" Animals 15, no. 24: 3600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243600

APA StyleYu, S., Jin, J., Zheng, M., Yin, F., Liu, W., Zhao, Z., Wang, L., & Chen, Y. (2025). Dietary Pineapple Pomace Complex Improves Growth Performance and Reduces Fecal Odor in Weaned Piglets by Modulating Fecal Microbiota, SCFAs, and Indoles. Animals, 15(24), 3600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243600