Clinical Evaluation of Autologous PRP (Platelet-Rich Plasma) in the Treatment of Periodontitis in Small-Breed Dogs

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Treatment

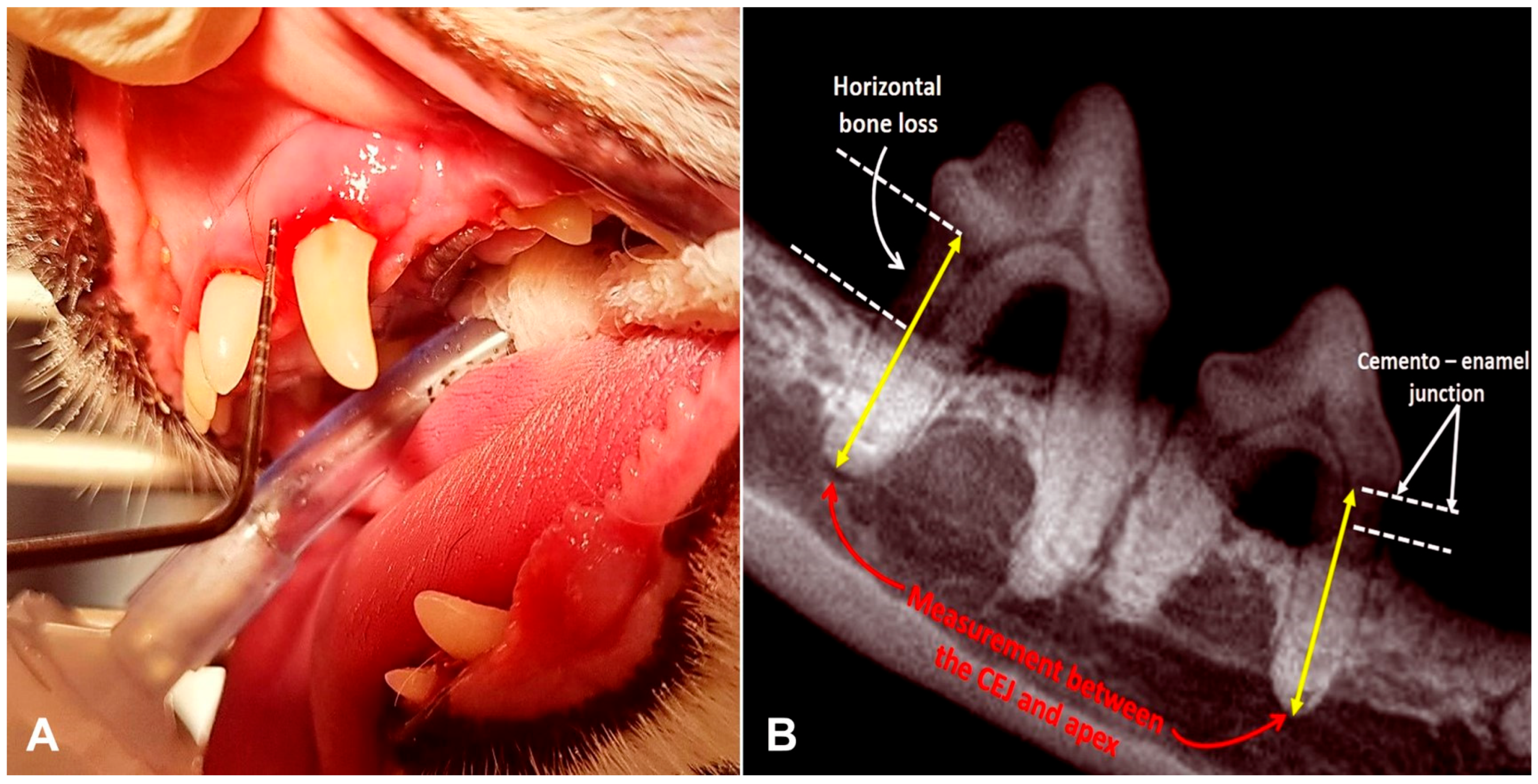

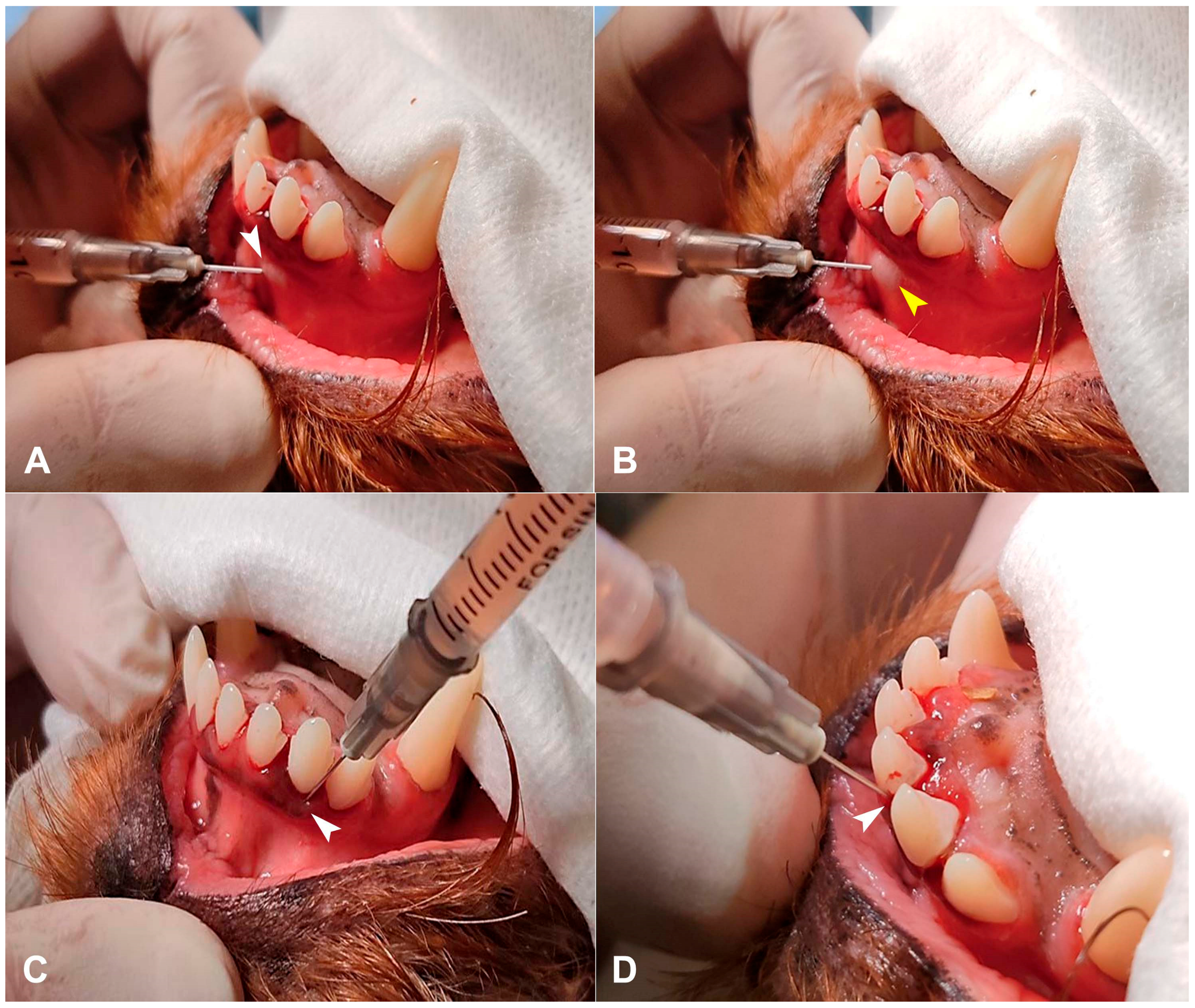

2.3. PRP Preparation and Injection

2.4. Follow-Up Evaluation

2.5. Study Selection

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Hematology and PRP Analysis

3.2. Periodontal Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PRP | Platelet-Rich Plasma |

| PDGF | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor |

| FGF | Fibroblast Growth Factor |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| EGF | Epidermal Growth Factor |

| PRF | Platelet-Rich Fibrin |

| PRGF | Plasma Rich In Growth Factors |

| CEJ | Cemento–Enamel Junction |

| ACP | Autologous Conditioned Plasma |

| i-PRF | Injectable Platelet-Rich Fibrin |

References

- Tambella, A.M.; Bartocetti, F.; Rossi, G.; Galosi, L.; Catone, G.; Falcone, A.; Vullo, C. Effects of Autologous Platelet-Rich Fibrin in Post-Extraction Alveolar Sockets: A Randomized, Controlled Split-Mouth Trial in Dogs with Spontaneous Periodontal Disease. Animals 2020, 10, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallis, C.; Holcombe, L.J. A Review of the Frequency and Impact of Periodontal Disease in Dogs. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2020, 61, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, M.O.; Dos Reis, L.D.; Lopes, W.R.; Schwarz, L.V.; Rocha, R.K.M.; Scariot, F.J.; Echeverrigaray, S.; Delamare, A.P.L. Bacterial Community Associated with Gingivitis and Periodontitis in Dogs. Res. Vet. Sci. 2023, 162, 104962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niemczyk, W.; Janik, K.; Żurek, J.; Skaba, D.; Wiench, R. Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) and Injectable Platelet-Rich Fibrin (i-PRF) in the Non-Surgical Treatment of Periodontitis—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Golub, L.M.; Lee, H.M.; Lin, M.C.; Bhatt, H.D.; Hong, H.L.; Johnson, F.; Scaduto, J.; Zimmerman, T.; Gu, Y. Chemically-Modified Curcumin 2.24: A Novel Systemic Therapy for Natural Periodontitis in Dogs. J. Exp. Pharmacol. 2020, 12, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobprise, H.B.; Dodd, J.R.B. (Eds.) Wiggs’s Veterinary Dentistry; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Santibáñez, R.; Rodríguez-Salas, C.; Flores-Yáñez, C.; Garrido, D.; Thomson, P. Assessment of Changes in the Oral Microbiome That Occur in Dogs with Periodontal Disease. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrel, C. Periodontal Disease—An Introduction. In Saunders Solutions in Veterinary Practice: Small Animal Dentistry; Gorrel, C., Ed.; Saunders: London, UK, 2008; pp. 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, C.S.; Wei, Y.F.; Lin, L.S. Submucosal Injection of Activated Platelet-Rich Plasma for Treatment of Periodontal Disease in Dogs. J. Vet. Dent. 2023, 40, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornsuthisopon, C.; Pirarat, N.; Osathanon, T.; Kalpravidh, C. Autologous Platelet-Rich Fibrin Stimulates Canine Periodontal Regeneration. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.G.; Kwon, D.; Lee, K.; Kim, S.E.; Jo, H.M. Prevalence of Reasons for Tooth Extraction in Small- and Medium-Breed Dogs. Animals 2025, 15, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallis, C.; Pesci, I.; Colyer, A.; Milella, L.; Southerden, P.; Holcombe, L.J.; Desforges, N. A Longitudinal Assessment of Periodontal Disease in Yorkshire Terriers. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, B.J.; Miller, A.V.; Colbath, A.C.; Peralta, S.; Frye, C.W. Literature Review Details and Supports the Application of Platelet-Rich Plasma Products in Canine Medicine, Particularly as an Orthobiologic Agent for Osteoarthritis. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2024, 262, S8–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suaid, F.F.; Carvalho, M.D.; Santamaria, M.P.; Casati, M.Z.; Nociti, F.H., Jr.; Sallum, A.W.; Sallum, E.A. Platelet-Rich Plasma and Connective Tissue Grafts in the Treatment of Gingival Recessions: A Histometric Study in Dogs. J. Periodontol. 2008, 79, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, N.P.; Adler, R.; Joss, A.; Nyman, S. Absence of Bleeding on Probing: An Indicator of Periodontal Stability. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1990, 17, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, P.F. Platelets Reduce Coronary Microvascular Permeability to Macromolecules. Am. J. Physiol. 1986, 251 Pt 2, H581–H587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchini, M.; Cruciani, M.; Mengoli, C.; Masiello, F.; Marano, G.; D’Aloja, E.; Dell’Aringa, C.; Pati, I.; Veropalumbo, E.; Pupella, S.; et al. The Use of Platelet-Rich Plasma in Oral Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Blood Transfus. 2019, 17, 357–367. [Google Scholar]

- Mościcka, P.; Przylipiak, A. History of Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma: A Short Review. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 2712–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnouf, T.; Goubran, H.A.; Chen, T.M.; Ou, K.L.; El-Ekiaby, M.; Radosevic, M. Blood-Derived Biomaterials and Platelet Growth Factors in Regenerative Medicine. Blood Rev. 2013, 27, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovic, V.; Ciric, M.; Jovanovic, V.; Stojanovic, P. Platelet-Rich Plasma: A Short Overview of Certain Bioactive Components. Open Med. 2016, 11, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladulescu, D.; Scurtu, L.G.; Simionescu, A.A.; Scurtu, F.; Popescu, M.I.; Simionescu, O. Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) in Dermatology: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Action. Biomedicines 2023, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karan, C.L.; Jeyaraman, M.; Jeyaraman, N.; Ramasubramanian, S.; Khanna, M.; Yadav, S. Antimicrobial Effects of Platelet-Rich Plasma and Platelet-Rich Fibrin: A Scoping Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e51360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohan Ehrenfest, D.M.; Rasmusson, L.; Albrektsson, T. Classification of Platelet Concentrates: From Pure Platelet-Rich Plasma (P-PRP) to Leucocyte- and Platelet-Rich Fibrin (L-PRF). Trends Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anitua, E.; Sánchez, M.; Orive, G.; Andía, I. The Potential Impact of the Preparation Rich in Growth Factors (PRGF) in Different Medical Fields. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 4551–4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harnack, L.; Boedeker, R.H.; Kurtulus, I.; Boehm, S.; Gonzales, J.; Meyle, J. Use of Platelet-Rich Plasma in Periodontal Surgery—A Prospective Randomised Double Blind Clinical Trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2009, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul Ameer, L.A.; Raheem, Z.J.; Abdulrazaq, S.S.; Ali, B.G.; Nasser, M.M.; Khairi, A.W.A. The Anti-Inflammatory Effect of the Platelet-Rich Plasma in the Periodontal Pocket. Eur. J. Dent. 2018, 12, 528–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatakeyama, I.; Marukawa, E.; Takahashi, Y.; Omura, K. Effects of Platelet-Poor Plasma, Platelet-Rich Plasma, and Platelet-Rich Fibrin on Healing of Extraction Sockets with Buccal Dehiscence in Dogs. Tissue Eng. Part A 2014, 20, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuki, H.; Okudera, T.; Watanebe, T.; Suzuki, M.; Nishiyama, K.; Okudera, H.; Nakata, K.; Uematsu, K.; Su, C.Y.; Kawase, T. Growth Factor and Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Contents in Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP), Plasma Rich in Growth Factors (PRGF), Advanced Platelet-Rich Fibrin (A-PRF), and Concentrated Growth Factors (CGF). Int. J. Implant. Dent. 2016, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirai, N.; Shirai, M.; Kato, Y.; Murakami, M.; Nomura, R.; Yamasaki, Y.; Takahashi, S.; Kondo, C.; Matsumoto-Nakano, M.; Nakano, K.; et al. Correlation of Age with Distribution of Periodontitis-Related Bacteria in Japanese Dogs. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2013, 75, 999–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Marcos Carpio, I.; Sanghani-Kerai, A.; Solano, M.A.; Blunn, G.; Jifcovici, A.; Fitzpatrick, N. Clinical Cohort Study in Canine Patients to Determine the Average Platelet and White Blood Cell Number and Its Correlation with Patient’s Age, Weight, Breed and Gender: 92 Cases (2019–2020). Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Adult small-breed dogs | Medium and large breed dogs |

| 3–4 years of age | Stage 1 and stage 4 periodontitis |

| Stage 2 or stage 3 periodontitis | Patients that have concomitant diseases |

| Dry food only | Patients who received home dental care |

| Patients who received medications or supplements |

| GI = 0 | healthy gums |

| GI = 1 | slight inflammation, possible slight discoloration or edema of the gums, no spontaneous bleeding on probing. |

| GI = 2 | moderate inflammation, red gums, pronounced edema, bleeding on probing. |

| GI = 3 | significant inflammation, pronounced gingival redness, edema and ulceration, characterized by spontaneous bleeding |

| Whole Blood | PRP | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red blood cells × 1012/L | 5.7 (5.5–7.4) | 6.4 (5.9–9.6) | 0.091372 |

| White blood cells × 109/L | 12.4 (5.8–15.8) 1 | 61.6 (59.2–124.7) 1 | 0.039731 |

| Neutrofils × 109/L | 7.7 (5.6–14.6) | 48.2 (26.4–88.8) | 0.682143 |

| Monocites × 109/L | 0.9 (0.74–1.1) | 7.8 (3.2–12.4) | 0.572324 |

| Platelets K/µL | 340 (228–416) 2 | 1288 (689–1517) 2 | 0.002516 |

| Stage of Periodontitis | Gingival Index | Periodontal Pocket Depth (mm) | Horizontal Bone Loss (mm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | PRP | Control | PRP | Control | PRP | Control | PRP | |

| Day 0 | 2 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | 2 (1–3) | 3 (2–3) | 4 (1–7) | 4 (1–8) | 3.91 (1.12–5.74) | 4.20 (1.18–8.54) |

| Day 30 | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) * | 1 (0–2) * | 3 (1–5) ** | 2 (1–4) ** | 4.65 (1.30–7.21) *** | 2.08 (1.03–5.35) *** |

| p | 0.025 | 0.000183 | 0.025 | 0.000074 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kvitka, D.; Jankauskas, M.; Klupšas, M.; Gradeckienė, A.; Juodžentė, D.; Rudenkovaitė, G. Clinical Evaluation of Autologous PRP (Platelet-Rich Plasma) in the Treatment of Periodontitis in Small-Breed Dogs. Animals 2025, 15, 3581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243581

Kvitka D, Jankauskas M, Klupšas M, Gradeckienė A, Juodžentė D, Rudenkovaitė G. Clinical Evaluation of Autologous PRP (Platelet-Rich Plasma) in the Treatment of Periodontitis in Small-Breed Dogs. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243581

Chicago/Turabian StyleKvitka, Dmitrij, Martinas Jankauskas, Matas Klupšas, Aistė Gradeckienė, Dalia Juodžentė, and Greta Rudenkovaitė. 2025. "Clinical Evaluation of Autologous PRP (Platelet-Rich Plasma) in the Treatment of Periodontitis in Small-Breed Dogs" Animals 15, no. 24: 3581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243581

APA StyleKvitka, D., Jankauskas, M., Klupšas, M., Gradeckienė, A., Juodžentė, D., & Rudenkovaitė, G. (2025). Clinical Evaluation of Autologous PRP (Platelet-Rich Plasma) in the Treatment of Periodontitis in Small-Breed Dogs. Animals, 15(24), 3581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243581