A Note on Some Health-Related Outcomes in Small Ruminant Farms with Common Grazing with Wildlife Ruminants

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Findings

3.2. Common Grazing with Wildlife Ruminants and Health-Related Outcomes

3.3. Significance of Common Grazing with Wildlife Ruminants as Predictor for Health-Related Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. Preamble

4.2. Faecal epg Counts

4.3. Bacterial Infections

4.4. Predictors

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Rural Development and Food, Hellenic Republic. Greek Agriculture—Animal Production; Ministry of Rural Development and Food, General Directorate for Animal Production: Athens, Greece, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pulina, G.; Milán, M.J.; Lavín, M.P.; Theodoridis, A.; Morin, E.; Capote, J.; Thomas, D.L.; Francesconi, A.H.D.; Caja, G. Current production trends, farm structures, and economics of the dairy sheep and goat sectors. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 6715–6729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Statistical Authority. Farm Structure Surveys; Hellenic Statistical Authority: Athens, Greece, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority. Scientific opinion on the welfare risks related to the farming of sheep for wool, meat and milk production. EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lianou, D.T. Mapping the Small Ruminant Industry in Greece: Health Management and Diseases of Animals, Preventive Veterinary Medicine and Therapeutics, Reproductive Performance, Production Outcomes, Veterinary Public Health, Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Farmers. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Thessaly, Volos, Greece, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Karmiris, I.E.; Nastis, A.S. Diet overlap between small ruminants and the European hare in a Mediterranean shrubland. Centr. Europ. J. Biol. 2010, 5, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billinis, C. Wildlife diseases that pose a risk to small ruminants and their farmers. Small Rumin. Res. 2013, 110, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, N.G.C.; Fthenakis, G.C.; Papadopoulos, E. Dissemination of parasites by animal movements in small ruminant farms. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 213, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzopoulos, D.C.; Valiakos, G.; Giannakopoulos, A.; Birtsas, P.; Sokos, C.; Vasileiou, N.G.C.; Papaspyropoulos, K.; Tsokana, C.N.; Spyrou, V.; Fthenakis, G.C.; et al. Bluetongue Virus in wild ruminants in Europe: Concerns and facts, with a brief reference to bluetongue in cervids in Greece during the 2014. Small Rumin. Res. 2015, 128, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridou, M.; Youlatos, D.; Lazarou, Y.; Selinides, K.; Pylidis, C.; Giannakopoulos, A.; Kati, V.; Iliopoulos, Y. Wolf diet and livestock selection in central Greece. Mammalia 2019, 83, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridou, M.; Benson, J.F.; Gimenez, O.; Iliopoulos, Y.; Kati, V. Do husbandry practices reduce depredation of free-ranging livestock? A case study with wolves in Greece. Biol. Cons. 2023, 283, 110097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsarou, E.I.; Lianou, D.T.; Michael, C.K.; Vasileiou, N.G.C.; Papadopoulos, E.; Petinaki, E.; Fthenakis, G.C. Associations of climatic variables with health problems in dairy sheep farms in Greece. Climate 2024, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. Manual of Veterinary Parasitological Laboratory Techniques; Her Majesty’s Stationery Office: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M.A.; Coop, R.L.; Wall, R.L. Veterinary Parasitology, 3rd ed.; Blackwell Publishing: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dohoo, I.; Martin, W.; Stryhn, H. Veterinary Epidemiologic Research, 3rd ed.; VER Inc.: Charlottetown, PE, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Beaumelle, C.; Redman, E.; Verheyden, H.; Jacquiet, P.; Bégoc, N.; Veyssière, F.; Benabed, S.; Cargnelutti, B.; Lourtet, B.; Poirel, M.T.; et al. Generalist nematodes dominate the nemabiome of roe deer in sympatry with sheep at a regional level. Int. J. Parasitol. 2002, 52, 751–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamsborg, S.M.; Jørgensen, R.J.; Waller, P.J.; Nansen, P. The influence of stocking rate on gastro-intestinal nematode infections of sheep over a 2-year grazing period. Vet. Parasitol. 1996, 67, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, A.R.; Begum, N.; Alim, M.A.; Malakar, S.; Islam, M.T.; Alam, M.Z. Gastro-intestinal nematodes in goats in Bangladesh: A large-scale epidemiological study on the prevalence and risk factors. Parasite Epidemiol. Contr. 2020, 9, e00146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsarou, E.I.; Arsenopoulos, K.V.; Michael, C.K.; Lianou, D.T.; Petinaki, E.; Papadopoulos, E.; Fthenakis, G.C. Gastrointestinal helminth infections in dogs in sheep and goat farms in Greece: Prevalence, involvement of wild canid predators and use of anthelmintics. Animals 2024, 14, 3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, A. Faecal Egg Counts. A Greener World Technical Advice Fact Sheet No. 22. Available online: https://agreenerworld.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/TAFS-22-Faecal-Egg-Counts-UK-v2.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- James, D. Faecal Egg Count Trial Cuts Wormer Use on Welsh Sheep Farms. Farmers Weekly, 4 February 2020. Available online: https://www.fwi.co.uk/livestock/health-welfare/livestock-diseases/parasitic-diseases/faecal-egg-count-trial-cuts-wormer-use-on-welsh-sheep-farms (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Miller, R.G. Simultaneous Statistical Inference, 2nd ed.; Springer Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, Y. Simultaneous and selective inference: Current successes and future challenges. Biometr. J. 2010, 52, 708–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.L.; Airs, P.M.; Porter, S.; Caplat, P.; Morgan, E.R. Understanding the role of wild ruminants in anthelmintic resistance in livestock. Biol. Lett. 2022, 18, 20220057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berri, M.; Rekiki, A.; Boumedine, K.S.; Rodolakis, A. Simultaneous differential detection of Chlamydophila abortus, Chlamydophila pecorum and Coxiella burnetii from aborted ruminant’s clinical samples using multiplex PCR. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodolakis, A. Q fever, state of art: Epidemiology, diagnosis and prophylaxis. Small Rumin. Res. 2006, 62, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chochlakis, D.; Santos, A.S.; Giadinis, N.D.; Papadopoulos, D.; Boubaris, L.; Kalaitzakis, E.; Psaroulaki, A.; Kritas, S.K.; Petridou, E.I. Genotyping of Coxiella burnetii in sheep and goat abortion samples. BMC Microbiol. 2018, 18, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridou, E.; Kiossis, E.; Chochlakis, D.; Lafi, S.; Psaroulaki, A.; Filippopoulos, L.; Baratelli, M.; Giadinis, N. Serological survey of Chlamydia abortus in Greek dairy sheep flocks. J. Hell. Vet. Med. Soc. 2022, 73, 4593–4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuteri, V.; Diverio, S.; Carnieletto, P.; Turilli, C.; Valente, C. Serological survey for antibodies against selected infectious agents among fallow deer (Dama dama) in central Italy. J. Vet. Med. B 1999, 46, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cubero-Pablo, M.J.; Plaza, M.; Perez, L.; Gonzalez, M.; Leon-Vizcaino, L. Seroepidemiology of chlamydial infections of wild ruminants in Spain. J. Wildl. Dis. 2000, 36, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, J.; Caro, M.R.; Vicente, J.; Cuello, F.; Reyes-Garcia, A.R.; Buendia, A.J.; Rodolakis, A.; Gortazar, C. High prevalence of antibodies against Chlamydiaceae and Chlamydophila abortus in wild ungulates using two “in house” blocking-ELISA tests. Vet. Microbiol. 2009, 135, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebani, V.V.; Trebino, C.; Guardone, L.; Bertelloni, F.; Cagnoli, G.; Altomonte, I.; Vignola, P.; Bongi, P.; Mancianti, F. Retrospective molecular survey on bacterial and protozoan abortive agents in roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) from Central Italy. Animals 2022, 12, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Barrio, D.; Almeria, S.; Caro, M.R.; Salinas, J.; Ortiz, J.A.; Gortazar, C.; Ruiz-Fons, F. Coxiella burnetii shedding by farmed red deer (Cervus elaphus). Transb. Emerg. Dis. 2015, 62, 572–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, M.; White, P.C.L.; Chambers, J.; Smith, L.; Hutchings, M.R. Wild deer as a source of infection for livestock and humans in the UK. Vet. J. 2007, 174, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huaman, J.L.; Helbig, K.J.; Carvalho, T.G.; Doyle, M.; Hampton, J.; Forsyth, D.M.; Pople, A.R.; Pacioni, C. A review of viral and parasitic infections in wild deer in Australia with relevance to livestock and human health. Wildl. Res. 2023, 50, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akwongo, C.J.; Borrelli, L.; Houf, K.; Fioretti, A.; Peruzy, M.F.; Murru, N. Antimicrobial resistance in wild game mammals: A glimpse into the contamination of wild habitats in a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Vet. Res. 2025, 21, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsby, D.T.; Zadoks, R.N.; Boyd, K.; Silva, N.; Chase-Topping, M.; Mitchel, M.C.; Currie, C.; Taggart, M.A. Antimicrobial resistant Escherichia coli in Scottish wild deer: Prevalence and risk factors. Environ. Poll. 2022, 314, 120129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branham, L.A.; Carr, M.A.; Scott, C.B.; Callaway, T.R. E. coli O157 and Salmonella spp. in white-tailed deer and livestock. Curr. Issues Intest. Microbiol. 2005, 6, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Althof, N.; Trojnar, E.; Johne, R. Rotaviruses in wild ungulates from Germany, 2019–2022. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore-Jones, G.; Arduser, F.; Durr, S.; Brawand, S.G.; Steiner, A.; Zanolari, P.; Ryser-Degiorgis, M.P. Identifying maintenance hosts for infection with Dichelobacter nodosus in free-ranging wild ruminants in Switzerland: A prevalence study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0219805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsarou, E.I.; Lianou, D.T.; Michael, C.K.; Petridis, I.G.; Vasileiou, N.G.C.; Fthenakis, G.C. Lameness in adult sheep and goats in Greece: Prevalence, predictors, treatment, importance for farmers. Animals 2024, 14, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lianou, D.T.; Arsenopoulos, K.V.; Michael, C.K.; Papadopoulos, E.; Fthenakis, G.C. Dairy goats helminthosis and its potential predictors in Greece: Findings from an extensive countrywide study. Vet. Parasitol. 2023, 320, 109962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lianou, D.T.; Arsenopoulos, K.V.; Michael, C.K.; Papadopoulos, E.; Fthenakis, G.C. Helminth infections in dairy sheep found in an extensive countrywide study in Greece and potential predictors for their presence in faecal samples. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lianou, D.T.; Chatziprodromidou, I.P.; Vasileiou, N.G.C.; Michael, C.K.; Mavrogianni, V.S.; Politis, A.P.; Kordalis, N.G.; Billinis, C.; Giannakopoulos, A.; Papadopoulos, E.; et al. A detailed questionnaire for the evaluation of health management in dairy sheep and goats. Animals 2020, 10, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lianou, D.T.; Michael, C.K.; Fthenakis, G.C. Data on mapping 444 dairy small ruminant farms during a countrywide investigation performed in Greece. Animals 2023, 13, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lianou, D.T.; Michael, C.K.; Petinaki, E.; Mavrogianni, V.S.; Fthenakis, G.C. Administration of vaccines in dairy sheep and goat farms: Patterns of vaccination, associations with health and production parameters, predictors. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Common Grazing | Frequency (Proportion) of Farms in Which Presence of Parasitic Elements of the Following Helminths Was Detected | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Dd 1 | Fh 1 | Pc 1 | Mon 1 | Trich Fam 1 | Tel 1 | Hc 1 | Trich 1 | Chab 1 | Coop 1 | Buno 1 | Nem 1 | Sp 1 | Trichur 1 | Lung 1 | epg 2 >300 | ||||||

| Yes (n = 36) | 5 (13.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.8%) | 6 (16.7%) | 36 (100.0%) | 36 (100.0%) | 36 (100.0%) | 34 (94.4%) | 27 (75.0%) | 16 (44.4%) | 5 (13.9%) | 9 (25.0%) | 2 (5.6%) | 9 (25.0%) | 7 (19.4%) | 13 (36.1%) | |||||

| No (n = 333) | 56 (16.8%) | 1 (0.3%) | 4 (1.2%) | 72 (21.6%) | 308 (92.9%) | 308 (92.5%) | 307 (92.2%) | 286 (85.9%) | 230 (69.1%) | 154 (46.2%) | 85 (25.5%) | 64 (19.2%) | 22 (6.6%) | 71 (21.3%) | 70 (21.0%) | 77 (23.1%) | |||||

| p-value | 0.65 | 0.74 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.46 | 0.84 | 0.12 | 0.41 | 0.81 | 0.61 | 0.82 | 0.08 | |||||

| Common Grazing | Median (Interquartile Range) of Respective Parameter in Faecal Samples | ||||||||||||||||||||

| epg | Proportion (%) Tel 1 | Proportion (%) Hc 1 | Proportion (%) Trich 1 | Proportion (%) Chab 1 | Proportion (%) Coop 1 | Proportion (%) Buno 1 | |||||||||||||||

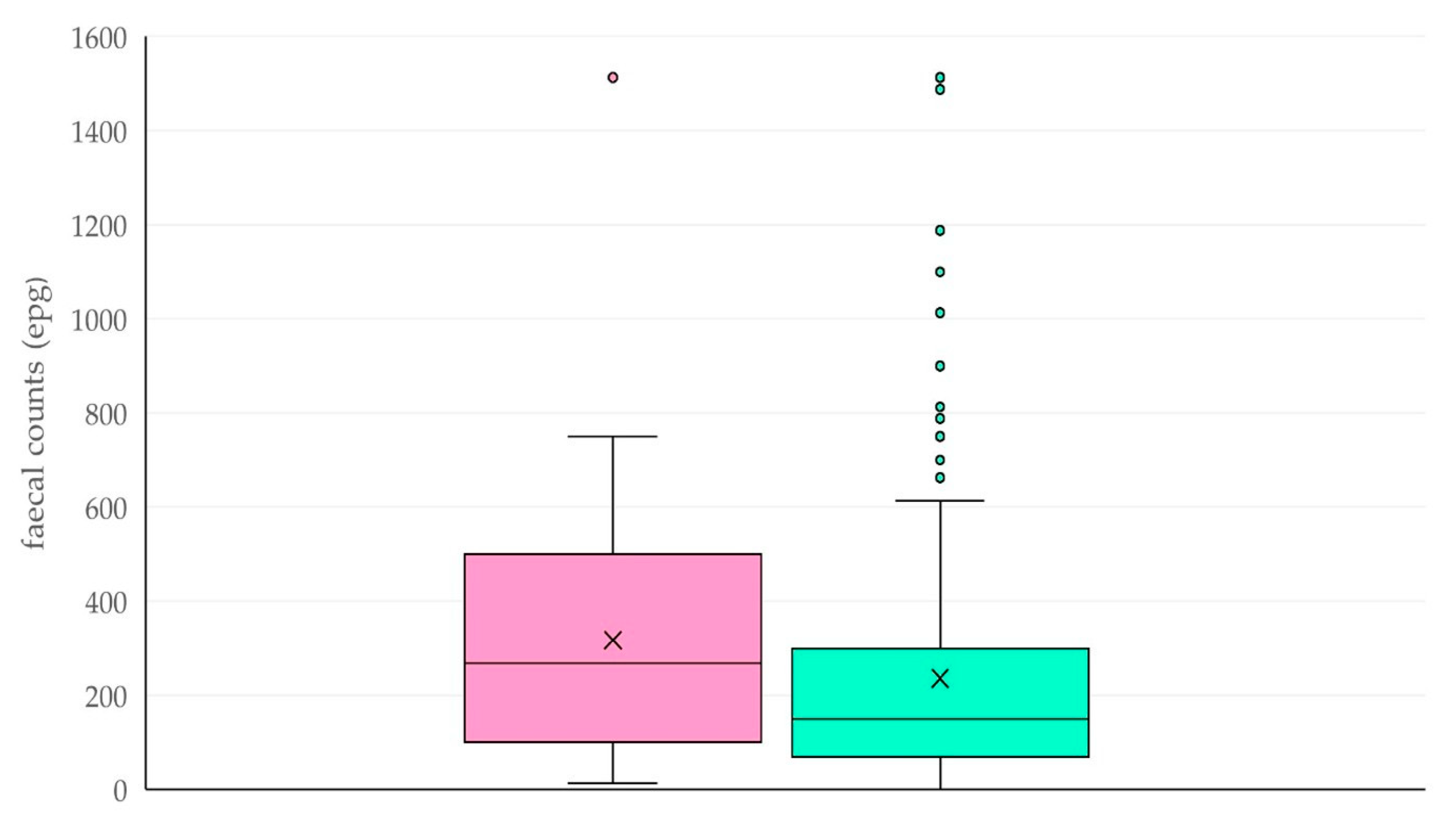

| Yes (n = 36) | 270 (400) | 60 (15) | 34 (16) | 3 (2) | 1 (0) | 0 (1) | 0 (0) | ||||||||||||||

| No (n = 333) | 150 (225) | 62 (14) | 31 (16) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 (1) | 0 (1) | ||||||||||||||

| p-value | 0.06 | 0.67 | 0.37 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.94 | 0.12 | ||||||||||||||

| Incidence of Cases of Abortion in Accordance with Livestock Species on Farms | |||

| Livestock Species | Common Grazing with Wildlife Ruminants | ||

| Yes (n = 41) | No (n = 403) | Yes (n = 41) | |

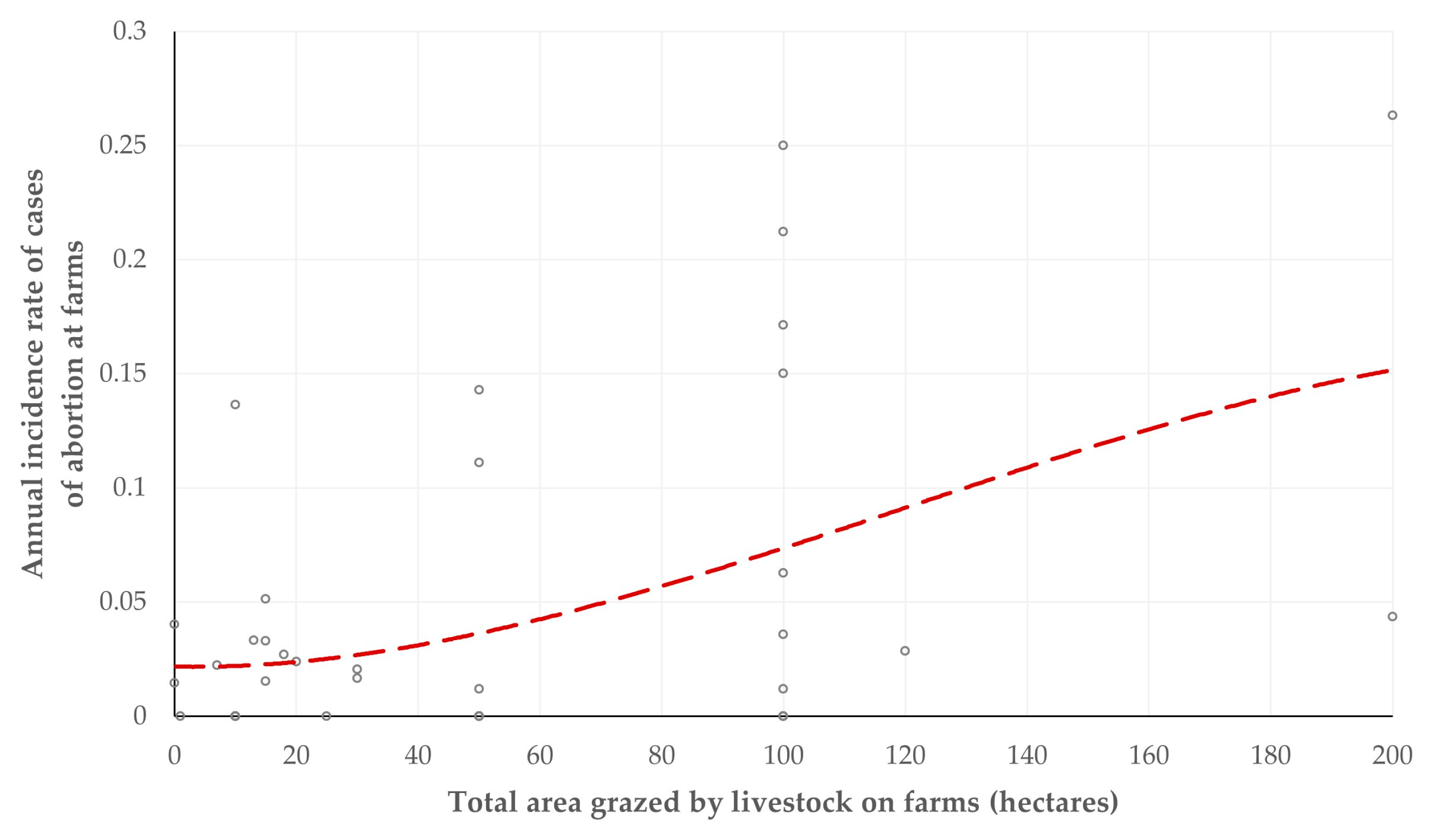

| Sheep (n = 325) | 1.6% (3.3%) | 0.0% (2.6%) | 0.05 |

| Goats (n = 119) | 0.0% (10.3%) | 0.0% (3.3%) | 0.29 |

| Incidence of Cases of Abortion in Accordance with Anti-Chlamydial Vaccination of Livestock on Farms | |||

| Vaccination Against Chlamydia psittaci | Common Grazing with Wildlife Ruminants | ||

| Yes (n = 41) | No (n = 403) | Yes (n = 41) | |

| No (n = 275) | 2.1% (4.2%) | 0.0% (2.9%) | 0.046 |

| Yes (n = 169) | 1.2% (7.6%) | 0.0% (2.9%) | 0.25 |

| Livestock Species | Common Grazing with Wildlife Ruminants | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 41) | No (n = 403) | Yes (n = 41) | |

| Sheep (n = 325) | 8.2% (16.8%) | 1.7% (9.0%) | 0.0008 |

| Goats (n = 119) | 13.9% (10.9%) | 1.8% (12.8%) | 0.048 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Katsarou, E.I.; Michael, C.K.; Arsenopoulos, K.V.; Lianou, D.T.; Liagka, D.V.; Mavrogianni, V.S.; Papadopoulos, E.; Fthenakis, G.C. A Note on Some Health-Related Outcomes in Small Ruminant Farms with Common Grazing with Wildlife Ruminants. Animals 2025, 15, 3579. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243579

Katsarou EI, Michael CK, Arsenopoulos KV, Lianou DT, Liagka DV, Mavrogianni VS, Papadopoulos E, Fthenakis GC. A Note on Some Health-Related Outcomes in Small Ruminant Farms with Common Grazing with Wildlife Ruminants. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3579. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243579

Chicago/Turabian StyleKatsarou, Eleni I., Charalambia K. Michael, Konstantinos V. Arsenopoulos, Dafni T. Lianou, Dimitra V. Liagka, Vasia S. Mavrogianni, Elias Papadopoulos, and George C. Fthenakis. 2025. "A Note on Some Health-Related Outcomes in Small Ruminant Farms with Common Grazing with Wildlife Ruminants" Animals 15, no. 24: 3579. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243579

APA StyleKatsarou, E. I., Michael, C. K., Arsenopoulos, K. V., Lianou, D. T., Liagka, D. V., Mavrogianni, V. S., Papadopoulos, E., & Fthenakis, G. C. (2025). A Note on Some Health-Related Outcomes in Small Ruminant Farms with Common Grazing with Wildlife Ruminants. Animals, 15(24), 3579. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243579