Outdoor Rearing and Behavioural Patterns in Diverse Rabbit Breeds: An Exploratory Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

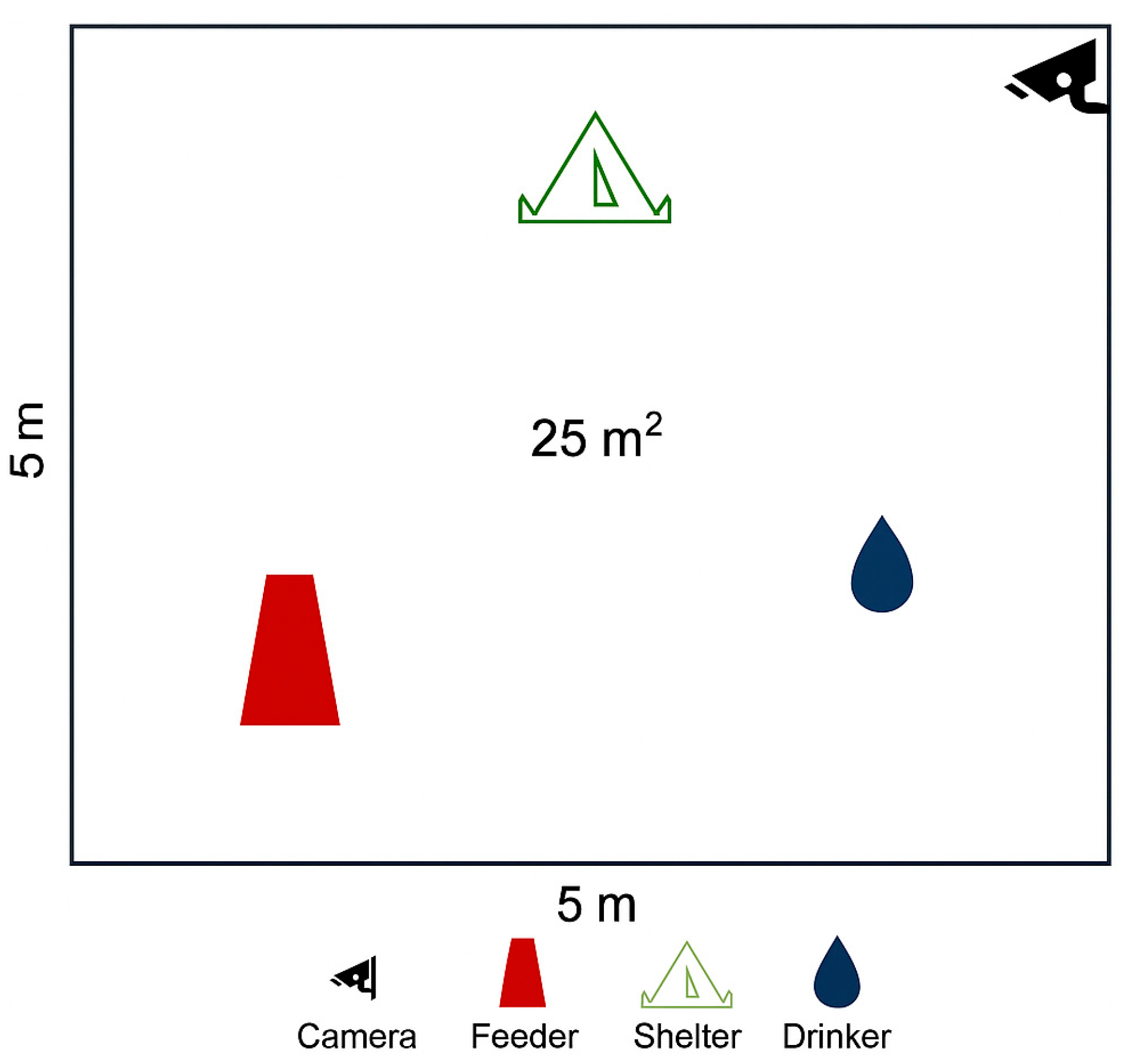

2.1. Animal and Housing Conditions

- GMs = grass mass present before animals entered each paddock

- GMe = grass mass remaining at the end of the sub-period

- GMu = undisturbed forage mass from the exclusion pens

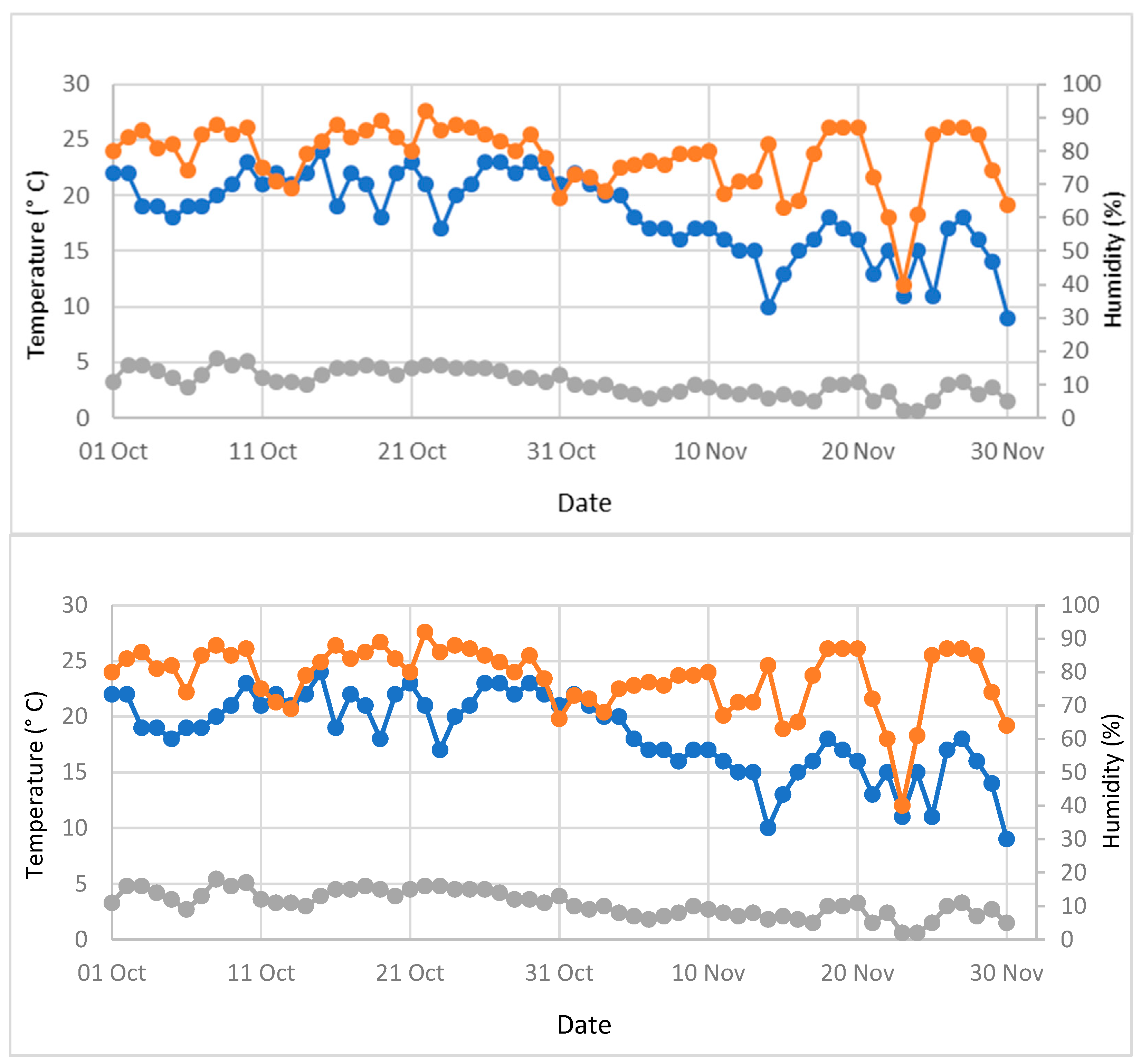

2.2. Environmental Conditions

2.2.1. Chemical Analysis of Feed and Grass

2.2.2. Behavioural Data

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

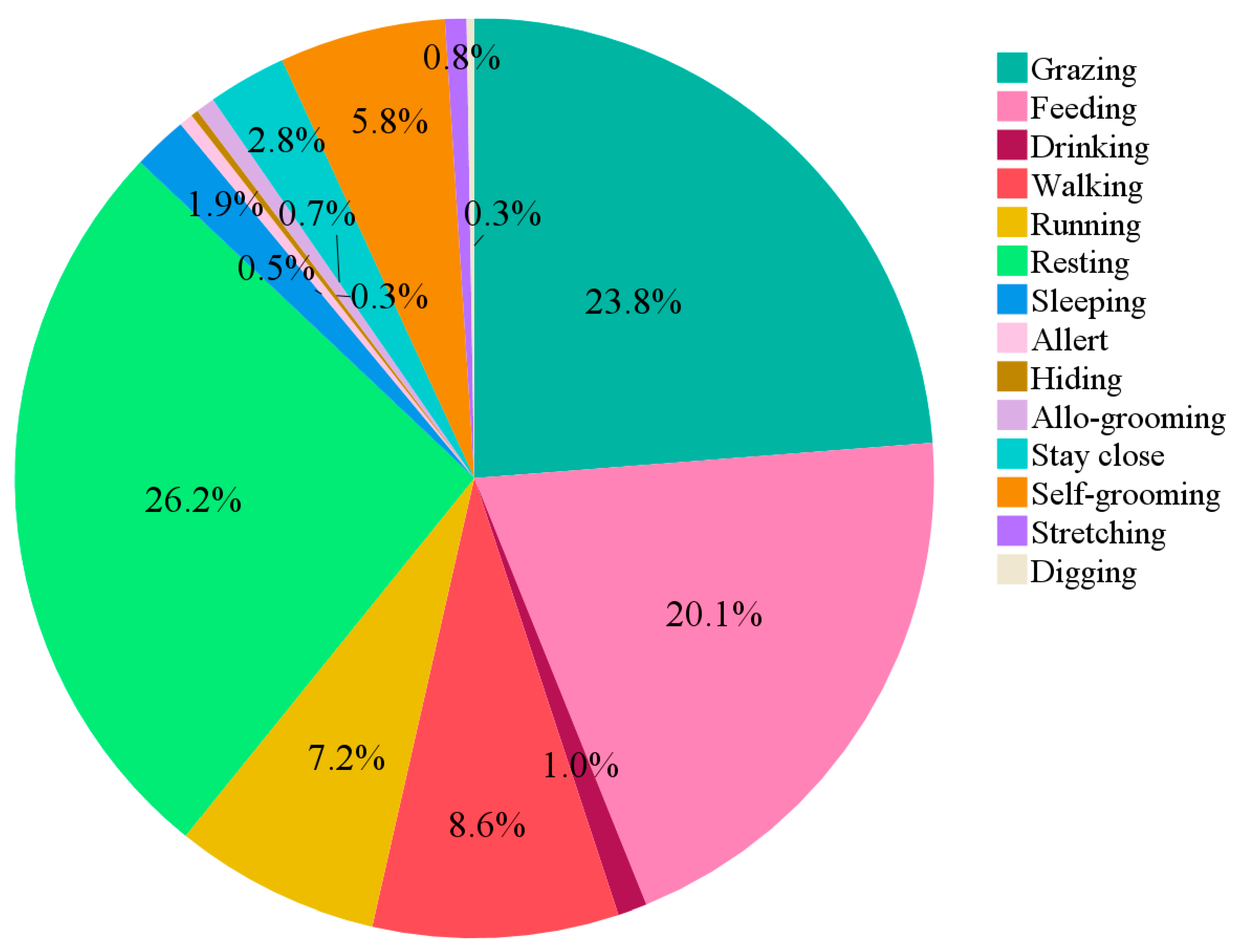

3.1. Effects of Circadian Timing, Age, and Breed on Individual Behaviours

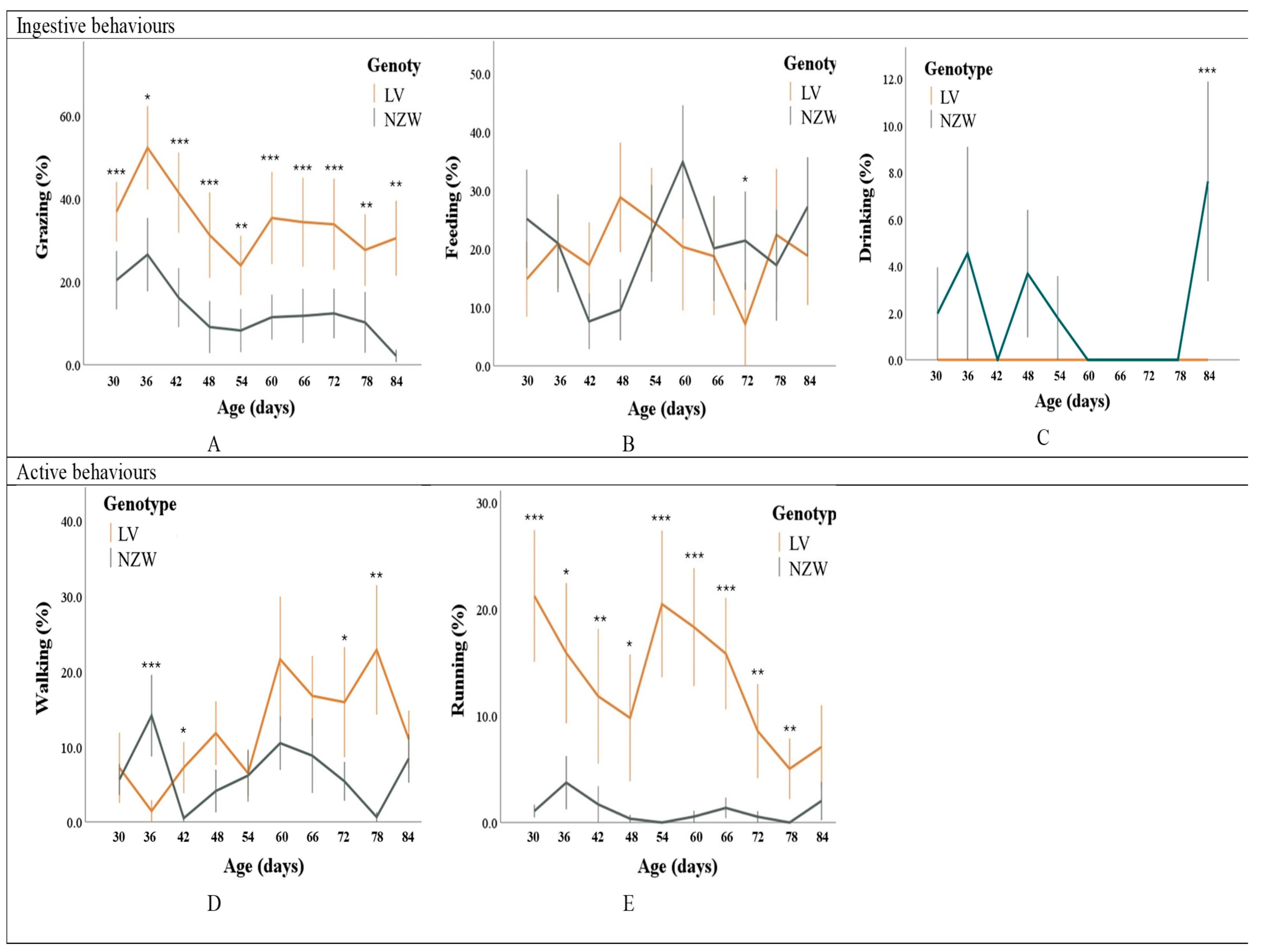

3.1.1. Ingestive Behaviours

3.1.2. Active Behaviours

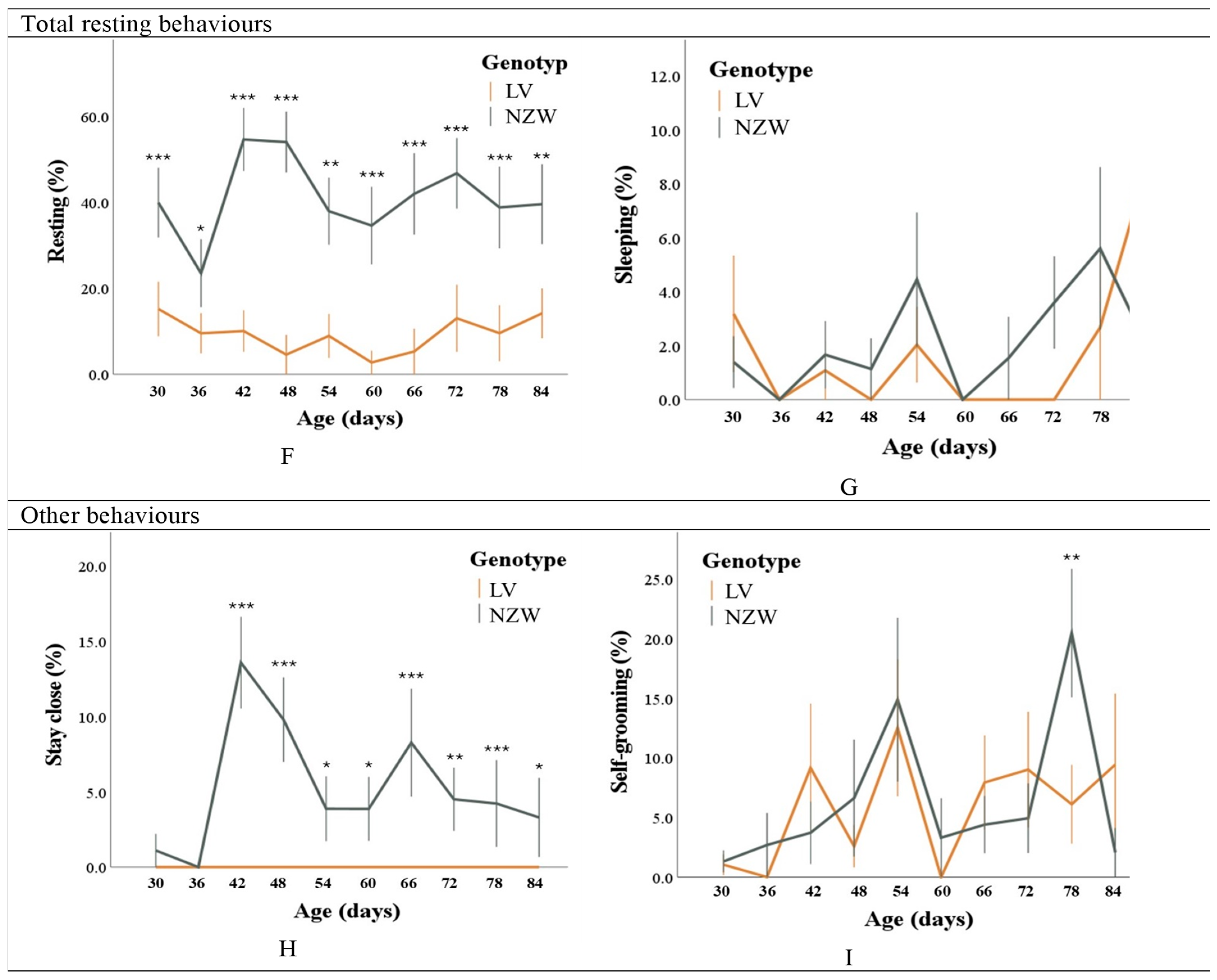

3.1.3. Total Resting Behaviours

3.1.4. Other Behaviours

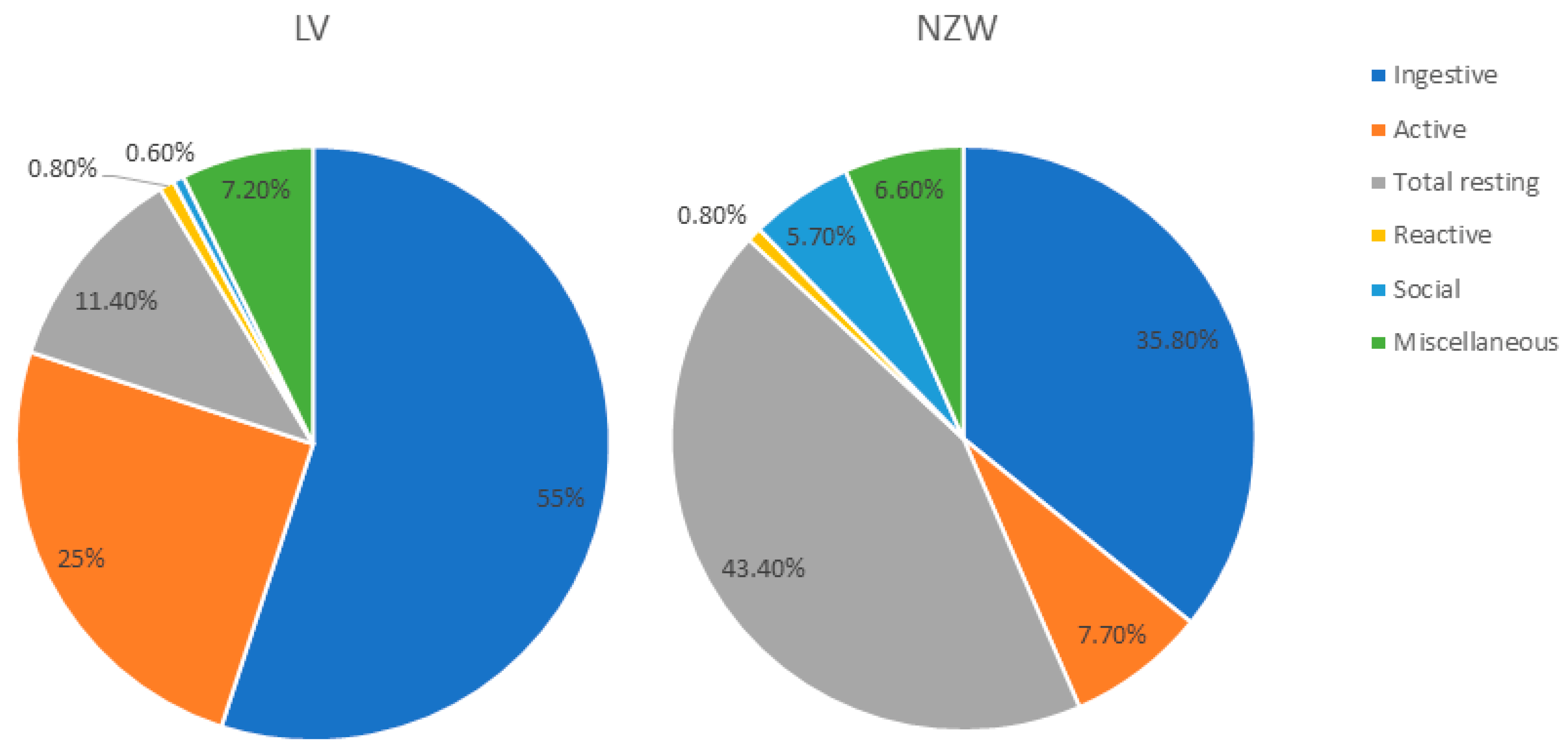

3.1.5. Behavioural Traits Distinguishing the Two Breeds

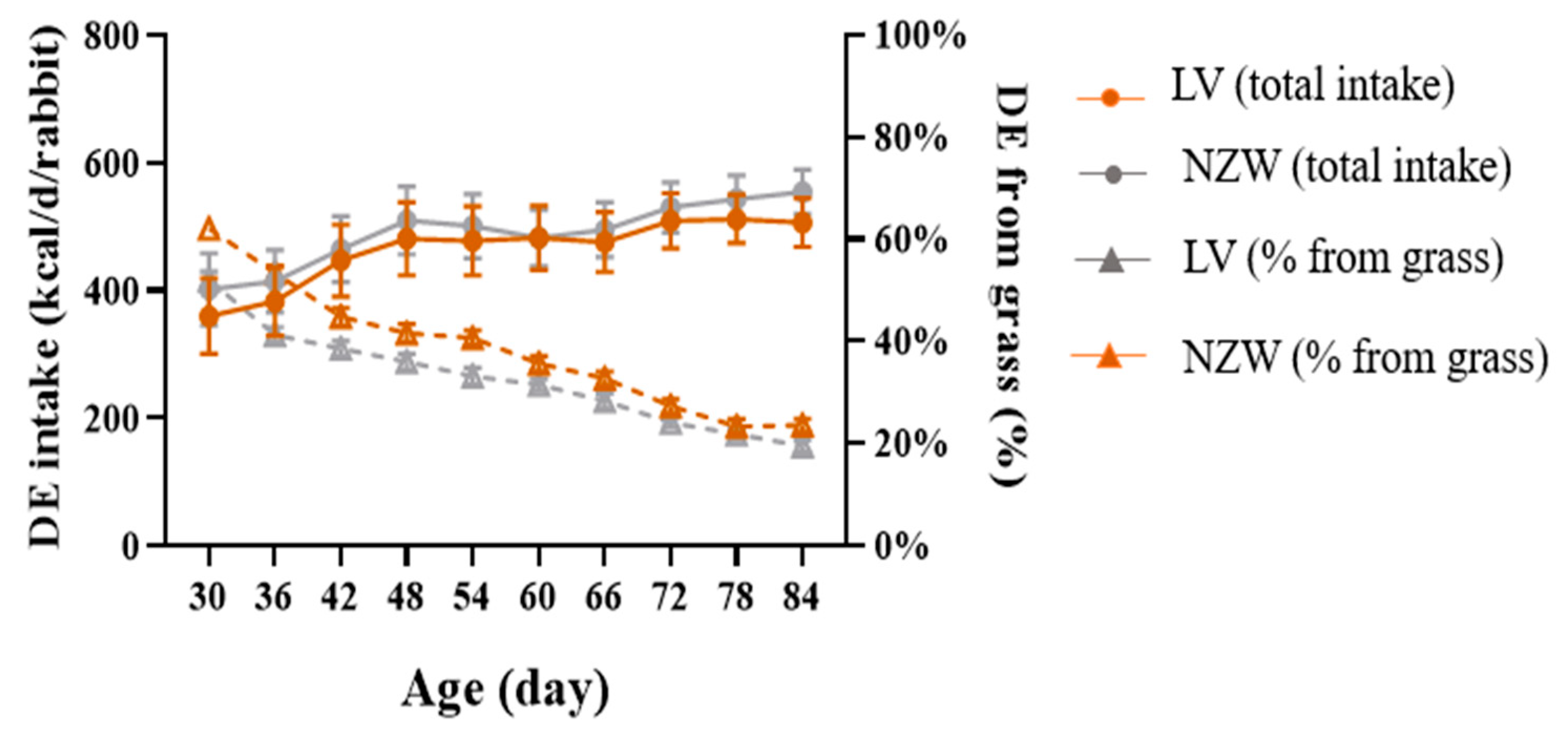

3.2. DE Intake and (%) DE from Grass

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Drescher, B. Housing of rabbits with respect to animal welfare. J. Appl. Rabbit Res. 1992, 15, 678–683. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante, V.; Verga, M.; Canali, E.; Mattiello, S.; Carenzi, C. Hybrid and New Zealand White rabbits kept in floor pens: Space distribution and aggregations. J. Appl. Rabbit Res. 1992, 15, 692–698. [Google Scholar]

- Morisse, J.P.; Boilletot, E.; Martrenchar, A. Grillage ou litière: Choix par le lapin et incidence sur le bien-être. In Proceedings of the 8èmes Journées de la Recherche Cunicole Française, Paris, France, 9–10 June 1999; pp. 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Vastrade, F.M. The social behaviour of free-ranging domestic rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus L.). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1986, 16, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council Directive 98/58/EC of 20 July 1998 on the Protection of Animals Kept for Farming Purposes. Official Journal of the European Communities. 1998. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:31998L0058 (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Pla, M. A comparison of the carcass traits and meat quality of conventionally and organically produced rabbits. Livest. Sci. 2007, 115, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordignon, F.; Xiccato, G.; Trocino, A.; Zuffellato, A.; Castellini, C.; Mattioli, S.; Berton, M. Environmental impact of rabbit production systems: A farm-based cradle-to-gate analysis. Animal 2025, 19, 101488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauss, M.; Burger, B.; Liesegang, A.; Del Chicca, F.; Kaufmann-Bart, M.; Riond, B.; Hatt, J.M. Influence of diet on calcium metabolism, tissue calcification and urinary sludge in rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus). J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2012, 96, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosa, L.; Molin, M.; Carnevali, A.; Petricciuolo, M.; Federici, E.; Trocino, A.; Xiccato, G.; Dal Bosco, A.; Mattioli, S.; Castellini, C. Performance, carcass and meat quality, fatty acid profile and fecal microbiota of rabbits fed an alfalfa-based diet. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 24, 1751–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.; Pilar, G.; Rebollar, P.G.; Mattioli, S.; Castellini, C. n-3 PUFA sources (precursor/products): A review of current knowledge on rabbit. Animals 2019, 9, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalle Zotte, A.; Cullere, M. Rabbit and quail: Little known but valuable meat sources. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 69, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothacher, M.; Hatt, J.M.; Clauss, M. A comparison of commercially available feeds for rabbits, guinea pigs, chinchillas and degus with evidence of their diet and feeding behaviour in natural habitats. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2023, 165, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kilkenny, C.; Browne, W.J.; Cuthill, I.C.; Emerson, M.; Altman, D.G. Improving Bioscience Research Reporting: The ARRIVE Guidelines for Reporting Animal Research. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian Republic. Legislative Decree No. 26 of 4 March 2014. Implementation of Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana, No. 61, 14 March 2014. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0015 (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Council Regulation (EC) No 1099/2009 of 24 September 2009 on the Protection of Animals at the Time of Killing. Off. J. Eur. Union. 2009. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=celex%3A32009R1099 (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Regulation (EC) No 834/2007 of 28 June 2007 on Organic Production and Labelling of Organic Products. Off. J. Eur. Union. 2007. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2007/834/oj/eng (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Comminssion Implementing Regulation(EU) 2020/464 of 26 March 2020 Laying Down Detailed Rules for Organic Production and Labelling of Organic Products. Off. J. Eur. Union. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_impl/2020/464/oj/eng (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Regulation (EU) 2018/848 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 on Organic Production and Labelling of Organic Products. Off. J. Eur. Union. 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2018/848/oj/eng (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Italian Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Forestry Policies. Ministerial Decree of 20 May 2022, No. 229771, on Organic Rabbit Farming and Outdoor Rearing Requirements; Ministry of Agriculture: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lantinga, E.A.; Keuning, J.A.; Groenwold, J.; Deenen, P.J.a.G. Distribution of excreted nitrogen by grazing cattle and its effects on sward quality, herbage production and utilization. In Animal Manure on Grassland and Fodder Crops. Fertilizer or Waste? Springer eBooks: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1987; pp. 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, R.; Rossini, F.; Ronchi, B.; Primi, R.; Stamigna, C.; Danieli, P.P. Potential of teff as alternative crop for Mediterranean farming systems: Effect of genotype and mowing time on forage yield and quality. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 17, 101257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis, 17th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis, 19th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis, 18th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.; Robertson, J.; Lewis, B. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Carmona, J.; Cervera, C.; Blas, E. Prediction of the energy value of rabbit feeds varying widely in fibre content. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1996, 64, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, S.; Menchetti, L.; Angelucci, E.; Cartoni Mancinelli, A.; Dal Bosco, A.; Madeo, L.; Di Federico, F.; Bosa, L.; Moscati, L.; Castellini, C. An index for the estimation of chicken adaptability to free-range farming systems of different slow-growing genotypes. Front. Anim. Sci. 2025, 6, 1648573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, M.S.; Downing, J.A.; Dyall, T.R.; Lee, C.; Campbell, D.L. Relationships Between Rearing Enrichments, Range Use, and an Environmental Stressor for Free-Range Laying Hen Welfare. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’agata, M.; Preziuso, G.; Russo, C.; Dalle Zotte, A.; Mourvaki, E.; Paci, G. Effect of an outdoor rearing system on the welfare, growth performance, carcass and meat quality of a slow-growing rabbit population. Meat Sci. 2009, 83, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozella, L.; Sartore, S.; Macchi, E.; Manenti, I.; Mioletti, S.; Miniscalco, B.; Crosetto, R.; Ponzio, P.; Fiorilla, E.; Mugnai, C. Behaviour and welfare assessment of autochthonous slow-growing rabbits: The role of housing systems. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA AHAW Panel (EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Welfare). Scientific opinion on the health and welfare of rabbits farmed in different production systems. EFSA J. 2020, 18, e05944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidenne, T.; Fortun-Lamothe, L.; Huang, Y.; Savietto, D. Pastured rabbit systems and organic certification: European Union regulations and technical and economic performance in France. World Rabbit Sci. 2024, 32, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losacco, C.; Tinelli, A.; Dambrosio, A.; Quaglia, N.C.; Passantino, L.; Schiavitto, M.; Passantino, G.; Laudadio, V.; Zizzo, N.; Tufarelli, V. Effect of rearing system (free-range vs. cage) on gut and muscle histomorphology and microbial loads of Italian White breed rabbits. Anim. Biosci. 2023, 37, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetiveau, M.; Savietto, D.; Fillon, V.; Bannelier, C.; Pujol, S.; Fortun-Lamothe, L. Effect of outdoor grazing-area access time and enrichment on space and pasture use, behaviour, health and growth traits of weaned rabbits. Animal 2023, 17, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattioli, S.; Angelucci, E.; Madeo, M.; Bonnefous, C.; Cartoni Mancinelli, A.; Ciarelli, C.; Collin, A.; Signorini, C.; Dal Bosco, A.; Oger, C.; et al. Effect of kinetic activity of slow-growing chickens on antioxidant, fatty acids profile, lipid oxidation and metabolism of blood and thigh muscles. Animal 2025, 19, 101569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goby, J.P.; Huck, C.; Fortun-Lamothe, L.; Gidenne, T. Intake growth and digestion of the growing rabbit fed alfalfa hay or green whole carrot: First results. In Proceedings of the 3rd ARPA Conference of Asian Rabbit Production Association, Denpasar, Indonesia, 27–29 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Joly, L.; Goby, J.P.; Duprat, A.; Legendre, H.; Savietto, D.; Gidenne, T.; Martin, G. PASTRAB—A model for simulating intake regulation and growth of rabbits raised on pastures. Animal 2018, 12, 1642–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, G.; Duprat, A.; Goby, J.; Theau, J.; Roinsard, A.; Descombes, M.; Legendre, H.; Gidenne, T. Herbage intake regulation and growth of rabbits raised on grasslands: Back to basics and looking forward. Animal 2016, 10, 1609–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plagnet, A.; Bannelier, C.; Fillon, V.; Savietto, D. Estimation of grass biomass consumed by rabbits housed in movable paddocks. World Rabbit Sci. 2023, 31, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredients | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Wheat bran | 27.0 | |

| Barley | 21.0 | |

| Hay | 17.0 | |

| Soybean meal | 14.0 | |

| Dehydrated alfalfa | 8.0 | |

| Sunflower meal | 8.0 | |

| Beet pulp | 2.0 | |

| Vegetable oil | 1.0 | |

| Vitamin and mineral supplement 1 | 1.0 | |

| Calcium carbonate | 0.5 | |

| NaCl | 0.5 | |

| Chemical composition (g/kg) | Diet | Grass |

| Dry matter | 882 ± 30 | 220 ± 10 |

| Crude protein | 164 ± 6 | 211 ± 8 |

| Crude fibre | 156 ± 8 | 331 ± 15 |

| Ether extract | 32.6 ± 1.5 | 183 ± 8 |

| Ash | 70.9 ± 2.9 | 81.1 ± 3.0 |

| NDF | 303 ± 12 | 585 ± 25 |

| ADF | 186 ± 8 | 328 ± 14 |

| Hemicellulose | 117 ± 5 | 273 ± 12 |

| Cellulose | 140 ± 6 | 220 ± 11 |

| ADL | 18.8 ± 1.0 | 76.4 ± 2.9 |

| Digestible energy (DE) (kcal/kg) 2 | 2.450 ± 80 | 1.810 ± 71 |

| Category | Behaviour | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Ingestive behaviours | Grazing | Eating grass directly from the ground, slowly and continuously |

| Feeding | Consumption of feed supplied | |

| Drinking | Drink water from drinker | |

| Active behaviours | Walking | Moving slowly on foot in a relaxed manner |

| Running | Moving quickly with accelerated steps, often in response to stimulation | |

| Total resting | Resting | Remaining still and relaxed, lying or standing quietly without sleeping |

| Sleeping | Being asleep with closed eyes and a relaxed body posture | |

| Reactive behaviours | Alert | Standing vigilant, head raised, ears forward, and attention directed to surroundings |

| Hiding | Staying behind objects, vegetation, or in shelter to avoid being seen | |

| Social behaviours | Allogrooming | Grooming, licking, or scratching another individual |

| Stay close | Remaining near a conspecific to maintain social contact | |

| Aggressive | Chasing, biting, or showing dominance towards another rabbit | |

| Miscellaneous | Self-grooming | Licking or scratching oneself to maintain cleanliness |

| Stretching | Extending body or limbs to loosen muscles | |

| Digging | Using hooves, paws, or snout to move soil and create holes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bosa, L.; Bernabucci, G.; Di Federico, F.; Nompleggio, L.; Vispi, M.; Menchetti, L.; Dal Bosco, A.; Mattioli, S.; Primi, R.; Girotti, P.; et al. Outdoor Rearing and Behavioural Patterns in Diverse Rabbit Breeds: An Exploratory Study. Animals 2025, 15, 3562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243562

Bosa L, Bernabucci G, Di Federico F, Nompleggio L, Vispi M, Menchetti L, Dal Bosco A, Mattioli S, Primi R, Girotti P, et al. Outdoor Rearing and Behavioural Patterns in Diverse Rabbit Breeds: An Exploratory Study. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243562

Chicago/Turabian StyleBosa, Luigia, Gloria Bernabucci, Francesca Di Federico, Lorenzo Nompleggio, Marta Vispi, Laura Menchetti, Alessandro Dal Bosco, Simona Mattioli, Riccardo Primi, Pedro Girotti, and et al. 2025. "Outdoor Rearing and Behavioural Patterns in Diverse Rabbit Breeds: An Exploratory Study" Animals 15, no. 24: 3562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243562

APA StyleBosa, L., Bernabucci, G., Di Federico, F., Nompleggio, L., Vispi, M., Menchetti, L., Dal Bosco, A., Mattioli, S., Primi, R., Girotti, P., & Castellini, C. (2025). Outdoor Rearing and Behavioural Patterns in Diverse Rabbit Breeds: An Exploratory Study. Animals, 15(24), 3562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243562