3. Results

3.1. Patients, Their Condition and Lameness Duration

A total of 78 joint capsule samples were examined for this study. Seventy-one dogs were presented due to hind limb lameness. Five of these dogs were later presented again due to lameness on the opposite side. Consequently, a total of 76 samples were obtained from surgical procedures, while 2 samples were collected post-mortem.

A medially directed patellar luxation was diagnosed in 59 cases (74%), and cruciate ligament rupture in 11 cases (16%). In cases of patellar luxation (PL), the condition was unilateral in 28 cases (47.46%) and bilateral in 31 cases (52.54%). A special group consisted of 4 dogs (5.13%) with both medial patellar luxation and cruciate ligament rupture (PL + CCLR). The control group included 4 dogs (5.13%) with other conditions (2 distal femoral fractures and 2 cases euthanized due to ileus or age-related euthanasia).

In the 59 cases of patellar luxation, the severity of the luxation varied significantly. The most commonly diagnosed grades that led to surgical intervention were grades 2, 3, and 4, with the diagnosis often depending on the examiner. In terms of frequency, 18 dogs (30.51%) were diagnosed with Grade 2 luxation; however, this grade was consistently identified by all examiners in only 6 cases (10.17%). Grade 3 was diagnosed 16 times (27.12%), while Grade 4 was identified and surgically treated in 4 cases (6.78%). Grade 1 patellar luxation was rarely observed, with only 2 instances recorded (3.39%). Additionally, 13 dogs (22.03%) exhibited luxation grades that fell between established categories: 3 dogs between Grades 1 and 2, 8 dogs between Grades 2 and 3, and 2 dogs between Grades 3 and 4.

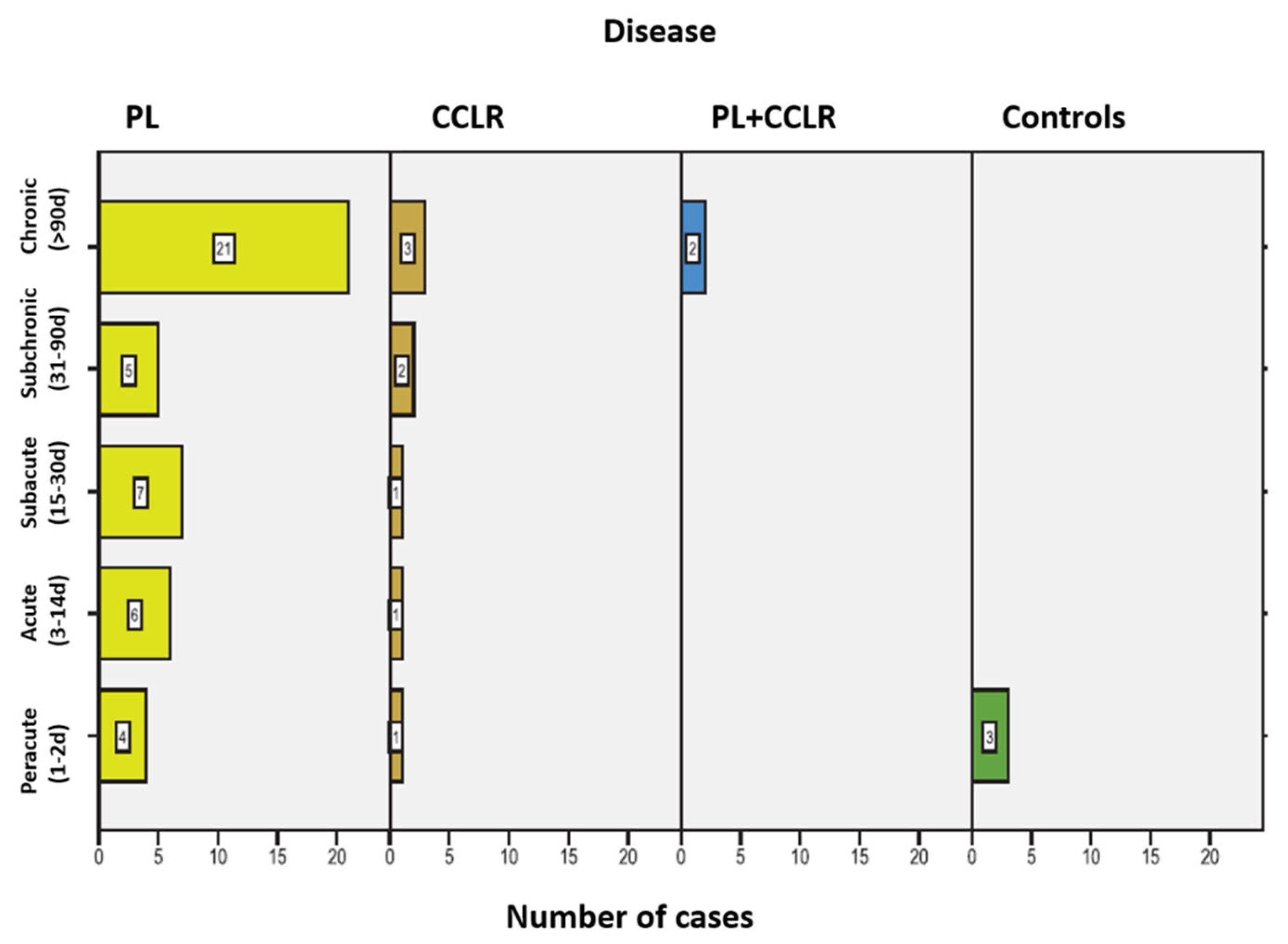

Lameness duration was recorded in the different patients and summarized in the following

Figure 5. In 20 patients (25.64%), the owners could not provide information on the duration of the lameness. Two control animals were not presented due to lameness but were included in the peracute lameness group.

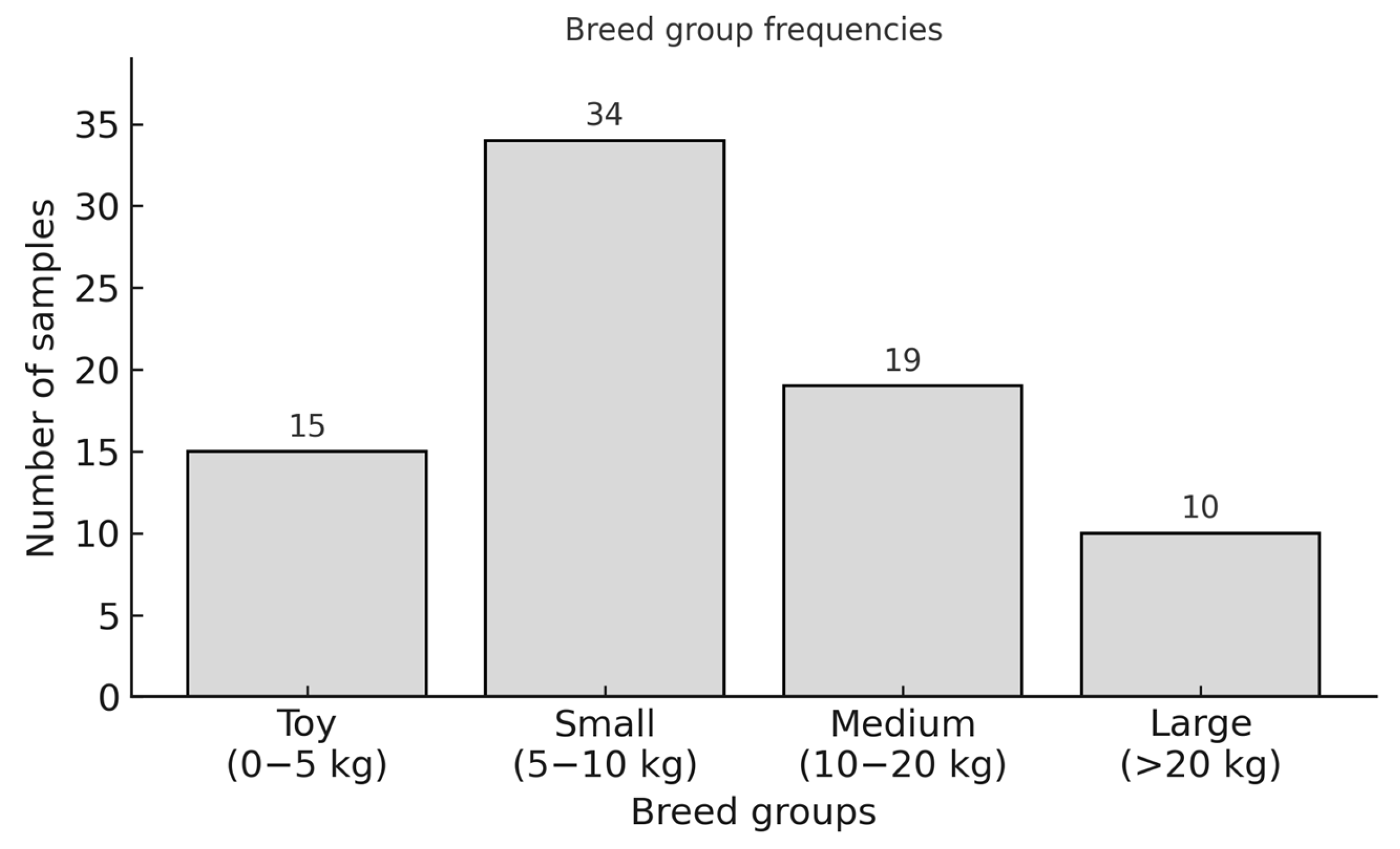

3.2. Breed Group Frequencies

The dogs of different breeds and mixed breeds were divided into four weight groups (

Figure 6).

In the PL group, Chihuahuas (n = 10) and Prague Rattlers (n = 2) were the most commonly represented breeds in the toy breed section, along with one Ruskiy Toy (n = 1). Among small breed dogs, mixed breeds (n = 6), Yorkshire Terriers (n = 5), and West Highland White Terriers (n = 3) were the most prevalent, with 14 additional cases from other breeds. In medium-sized breeds, mixed breeds (n = 5) and Shar-peis (n = 2) were most frequently observed, alongside seven other breeds. The large breed group included one German Shepherd, one Akita Inu, one American Staffordshire Terrier, and one mixed breed.

In the CCLR group, the toy breed category included one Chihuahua mix, while the small breed category featured one Shih Tzu. The medium-sized breed group consisted of one Tibetan Terrier, one Beagle, one Collie mix, and one mixed breed. The large breed category included two Boxers, one Caucasian Ovcharka mix, one Leonberger, and one Great Dane.

The PL + CCLR group, consisting of four individuals, equally represented the Yorkshire Terrier, Maltese, West Highland White Terrier, and a medium-sized mixed breed.

In the Control group (

n = 4), breeds were equally represented by a Chihuahua, Miniature Poodle, a medium-sized mixed breed, and an American Staffordshire Terrier. The exact breed distribution is shown in

Supplementary Table S3.

3.3. Age Characteristics of the Study Population

The age distribution of all patients ranged from 4 months to 15 years, with a mean age of 4.72 years and a median age of 4.00 years.

In the PL group, patient ages ranged from 0.5 years to 15 years, with a mean age of 4.22 years and a median age of 3.5 years. For the CCLR group, the minimum age was 2.5 years, and the maximum age was 12 years, with a mean age of 6.00 years and a median age of 11 years. In the PL + CCLR group, ages ranged from 4.5 years to 10 years, with a mean age of 7.3 years and a median age of 7.38 years. Finally, the Control group had patients ranging from 0.3 years to 15 years, with a mean age of 5.70 years and a median age of 3.75 years.

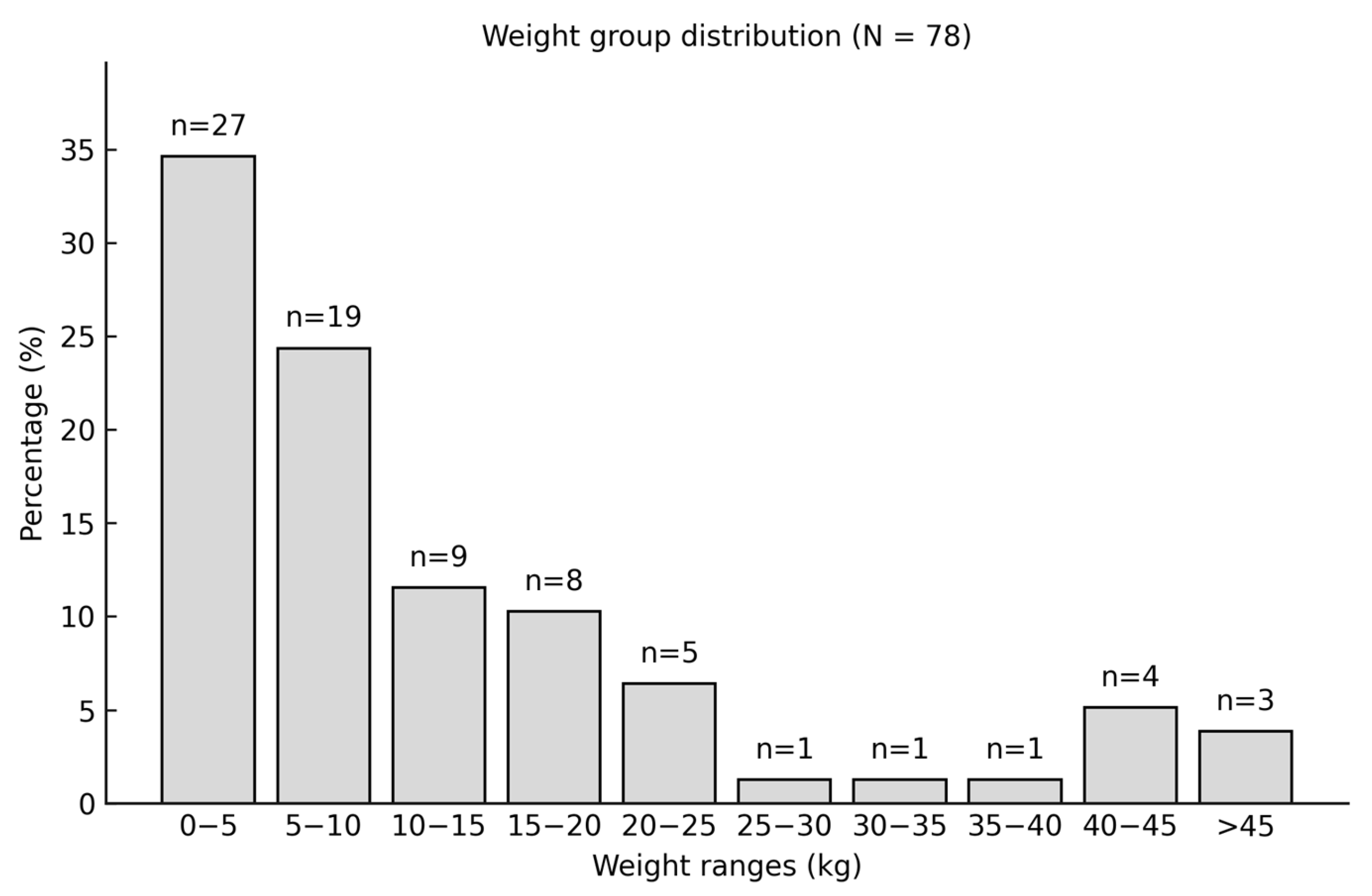

3.4. Body Weight Distribution

To better understand the distribution of body weight in the study population, the dogs were categorized into 10 weight classes, each with a range of 5 kg. This classification provides a clear overview of the weight distribution among the patients (

Figure 7).

3.5. Gender Distribution and Characteristics

The study analyzed gender distribution among the canine patients, comprising 43 males and 35 females. Of the male dogs, 10 (29%) were neutered, while 16 females (37%) were spayed. No significant gender predisposition was identified for any specific condition.

Congenital patellar luxation was observed slightly more often in females (54.24%, n = 32) compared to males (45.76%, n = 27). Regarding cruciate ligament ruptures, 6 females and 5 males were affected, with one neutered dog in each group. In cases of concurrent patellar luxation and cruciate ligament rupture, 3 out of 4 dogs were female (75%), 2 of which were spayed, while the only male was neutered. Among the control group of four dogs, 2 were female and 2 were male, with one neutered individual. Overall, the findings suggest a balanced gender distribution among the study population, with no statistically significant gender differences in the prevalence of the conditions examined.

3.6. Histological Results

The histological stains were used to illustrate different structures in the 78 joint capsule biopsies, which will be presented in the following chapters.

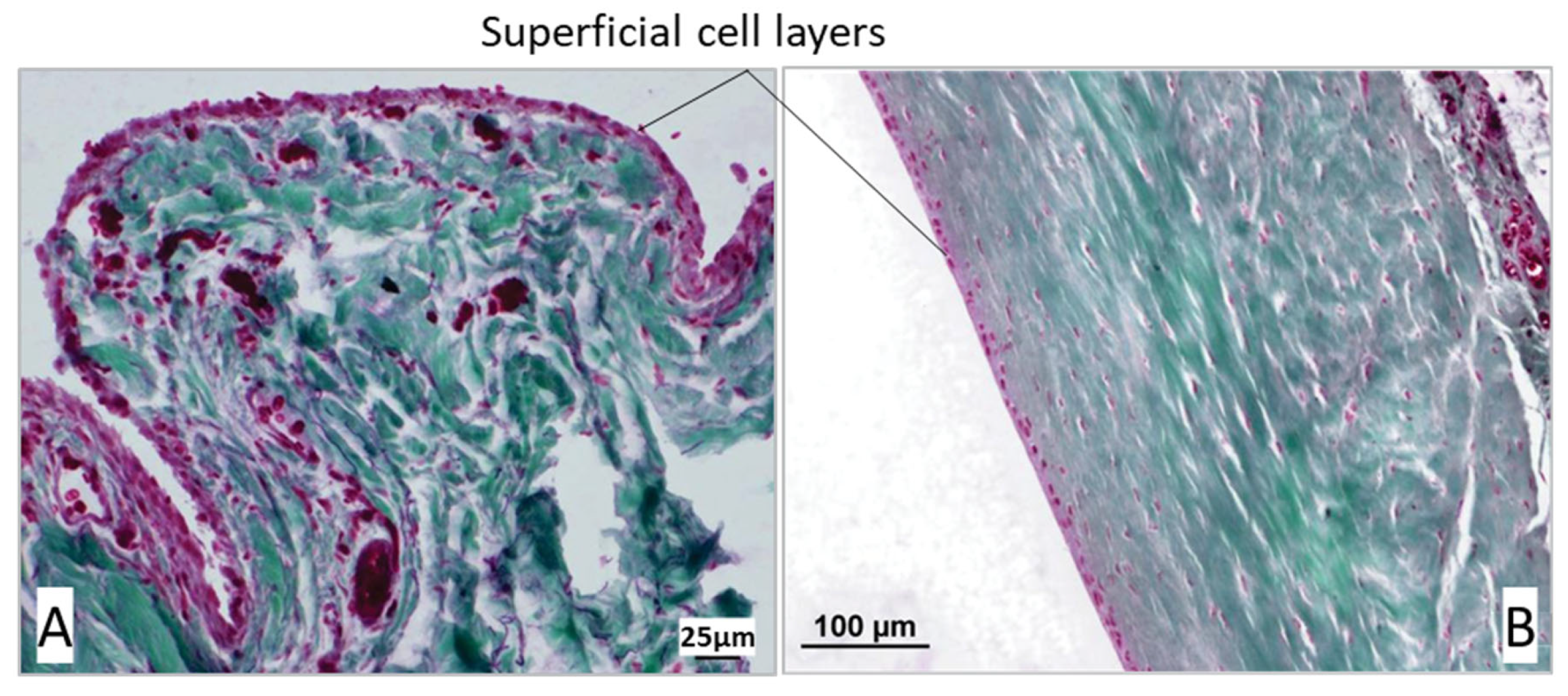

3.6.1. Characteristics of the Superficial Cell Layer

Two-thirds of the samples (

n = 48, 61.54%) showed a single-layer superficial cell layer in at least one of the three measured areas (proximal, middle, and distal sections of the joint capsule samples). Among these, the superficial cell layer was single-layered in 8 cases (10.26%) across two of the three measurement areas, while in 3 samples (3.85%), the superficial cell layer consisted of a single cell layer in all three sections of the joint capsule (

Figure 8B).

A multilayered superficial cell layer was defined as having more than 3 overlapping layers (

Figure 8A). In 73.08% (

n = 57) of the biopsies, the superficial cell layer was multilayered in at least one of the three measurement areas. The greatest variation in the number of superficial cells was observed in the middle section of the joint capsule, where the superficial cell layer of the stratum synoviale ranged from 1 to 15 layers. In contrast, the least variation was noted distally in the stratum synoviale, with between 1 and 8 superficial cell layers. The mean number of superficial cell layers in the proximal stratum synoviale was 3.88, which significantly differed from the mean of 2.66 in the middle section of the joint capsule (

p = 0.004). Mean values from the other sections did not differ significantly from each other (

Table 1).

The mean number of superficial cell layers in the proximal joint capsule section was similar among dogs with patellar luxation (mean = 4.03), those with cruciate ligament rupture, and those with both conditions. The mean value was lower in the control group. However, this difference was not statistically significant (

p > 0.005) (

Table 1).

Correlation Between Superficial Cell Layers and Disease

In the middle and distal joint capsule sections, greater fluctuations were observed between the individual groups, with the dogs in the control group showing the lowest mean value. However, there were no significant differences in the number of superficial cell layers between the control group and the other groups in these two measurement areas (

p > 0.005). Dogs with both patellar luxation and an additional cranial cruciate ligament rupture, representing patients with a chronic-progressive disease course (longer duration of lameness), had the highest average number of superficial cell layers in the stratum synoviale. Conversely, dogs in the control group, characterized by acute lameness (no lameness to 1–2 days duration), had the lowest number of superficial cell layers (

Figure 9).

Correlation Between the Superficial Cell Layers and Breed Groups

While differences in the mean number of superficial cell layers among the four breed groups were observed in the three joint capsule sections, these variations were not statistically significant. In toy, small, and medium-sized dog breeds, the middle section consistently showed fewer superficial cell layers on average compared to the proximal and distal sections. Large dog breeds were an exception to this pattern. For toy, small, and medium-sized breeds, the proximal section had the highest average number of superficial cell layers (

Supplementary Figure S1). Breed group had no significant influence on the number of superficial cell layers in any of the three joint capsule sections (

p > 0.005).

Correlation Between Superficial Cell Layers and Duration of Lameness/Disease Progression

The mean number of superficial cell layers in the three joint capsule sections varied considerably with different durations of lameness; however, no statistically significant differences were observed (

p > 0.005). On average, the middle superficial cell layer consistently exhibited the fewest cell layers compared to the superficial cell layers of the proximal and distal joint capsule sections across all forms of lameness progression. Notably, the smallest variation in values was observed during the peracute stage of lameness (

Supplementary Figure S2), with 75% of the control samples showing the least variation. Peracute lameness was associated with the lowest number of superficial cell layers compared to other durations.

Correlation Between Superficial Cell Layers and Age of the Patients

No correlation was found between the superficial cell layer and the age of the patients (

p > 0.005). In none of the three joint capsule sections was there a direct relationship between the number of superficial cell layers and patient age. The middle superficial cell layer consistently exhibited the fewest cell layers across nearly all age groups (

Supplementary Table S4).

3.6.2. Surface Enlargement Factor—SEF

The Surface Enlargement Factor (SEF) quantifies villus formation on the inner surface of the joint capsule and serves as a grading system for this formation. The cases were categorized into three distinct groups based on the SEF values. A value of 1, observed in 3 cases (3.85%), indicates the absence of villi (

Figure 10A). This value is derived from the ratio of the length of a smooth surface without villi to an equally long, parallel straight line. Values greater than 1 signify the presence of villi and are further subdivided: 41 cases (52.56%) had few or short villi (1 < SEF ≤ 2.5) (

Figure 10B), while 26 cases (33.33%) exhibited many or long villi (2.5 < SEF ≤ 5) (

Figure 10C). In 8 cases (10.26%), measurements could not be obtained due to the absence of the synovial layer, often resulting from tear-off or preparation damage. In total, 78 cases were assessed. The correlations between villus formation and patient signalment, along with data from the patients’ medical records, are discussed in the following section.

Correlation Between SEF and Disease

The mean values of the surface enlargement factors across different diseases show minimal variation. However, the group of dogs with PL (

n = 52; 66.66%) exhibits a significantly greater variation in villus formation compared to the control group.

Table 2 provides an overview of the mean values of the surface enlargement factors for the various diseases. In cases of patellar luxation (PL), some specimens displayed no villi (

n = 2; 2.56%), while others had the highest counts of villi (

n = 16; 20.51%). Most dogs with patellar luxation (

n = 34; 43.59%) showed few or small villi. Similarly, among the 11 dogs with CCLR, small or few villi were the most commonly observed (

n = 6; 7.69%). One case (1.28%) had no villi, and four cases exhibited very large or numerous villi (5.13%). In dogs with PL + CCLR, small or few villi were present in one case (1.28%), while tall or numerous villi were found in two cases (2.56%). All dogs in the comparison group (controls;

n = 4; 5.13%) exclusively displayed tall or particularly numerous villi.

Correlation Between SEF and Luxation Grades of Patellar Luxation

There was no statistical correlation found between SEF and the severity of patellar luxation. For Grade 1–2 and Grade 2, the median SEF values were slightly above 2.0, with narrow ranges between 1.5 to 2.0 and 2.0 to 3.0, respectively. In grades ≥ 2, the median was just above 2.0, with a range between 1.0 and 3.0. Grade 3 showed a median SEF slightly above 2.0, but with a wider range from about 1.0 to 4.0. Grade 4 had a median value of 2.0, with a narrower range, approximately between 1.0 and 2.0 (

Supplementary Figure S3).

Correlation Between SEF and Disease Progression/Duration of Lameness

On average, cases with a subchronic course exhibited the largest villi (SEF = 2.92) and also showed the greatest variability, with a minimum value of 1 and a maximum of 4.94. The group with a peracute disease course displayed a similar range in the mean values of the surface enlargement factors, with minimum and maximum values of 1.09 and 4.86, respectively. In contrast, smaller villi were more commonly observed in cases of subacute and chronic-progressive lameness, while peracute, acute, and subchronic forms of lameness tended to develop larger villi (

Supplementary Table S5 and

Figure S4).

Correlation Between SEF and Breed Groups

The mean values of the surface enlargement factors among the four breed groups showed minimal differences. Toy and small dog breeds exhibited, on average, villi of comparable size to those found in medium and large dog breeds. Notably, small dogs displayed the greatest variation in surface factors, with some individuals having the largest villi (SEF = 4.94) while others had no villi at all (SEF = 1.00). The variation, mean values, and extreme values for toy and large breeds were similar. Consequently, no proportional relationship between villus size and a dog’s body size could be established (

p > 0.005) (

Supplementary Table S6).

Correlation Between SEF and Age of the Patients

There is no correlation between the age of the patients and the surface enlargement factor. Young patients under one year of age have an average surface enlargement factor between 1.88 (small villi) and 2.99 (large villi). The mean values of the surface enlargement factors for older animals mostly lie between these two values. Therefore, no influence of age on the formation of villi could be demonstrated (

p > 0.005).

Supplementary Figure S5 illustrates the irregular distribution of the surface factors with respect to the age of the individual patients.

Correlation Between Villous Surface and Number of Superficial Cell Layers

In terms of their apical closure by the covering cells, no significant correlation could be established between the degree of villus formation and the number of covering cell layers in the three sections of the joint capsule. Apical closure refers to the sealing of the tips of the villi by the covering cells, which is important for maintaining the integrity of the joint capsule. Consequently, small villi can have as many or as few covering cell layers as large villi.

3.7. Absence of the Middle Stratum Subsynoviale

During the histomorphological examinations, it was observed that the stratum subsynoviale was absent in the middle section of the stifle joint capsule samples in 59 out of 78 cases (75.64%). As a result, the stratum synoviale was directly adjacent to the stratum fibrosum. This phenomenon was not observed in the proximal and distal sections of the joint capsule, where all three layers were always present (

Figure 11A,B).

3.7.1. Correlation Between Breed and Absence of the Stratum Subsynoviale in the Middle Section

The frequency of the presence of the stratum subsynoviale in the middle section of the stifle joint capsule was evaluated based on breed group. The middle section of the stratum subsynoviale was absent in nearly three-quarters of cases across toy, small, medium, and large dogs. No significant correlation between breed and the absence of the middle stratum subsynoviale was found (

p > 0.005) (

Supplementary Table S7).

3.7.2. Correlation Between Age and Absence of the Stratum Subsynoviale in the Middle Section

In the age range of 0.3 to 1.0 years, the stratum subsynoviale was primarily present, although in limited samples. From 1.0 to 4.5 years, there was a notable increase in samples where this stratum was absent, leading to a decrease in its presence. By the age of 5.0 years, it was predominantly absent, with only a few instances noted at 5.5, 8.0, and 10.0 years. Overall, the data indicated that the absence of the stratum subsynoviale became more common with increasing age, particularly between 2.0 and 7.0 years. However, despite these findings, no significant correlation between age and the absence of the stratum subsynoviale was observed (

p > 0.005) (

Supplementary Figure S6).

3.7.3. Correlation Between Weight Classes and Absence of the Stratum Subsynoviale in the Middle Section

No correlation was found between the absence of the stratum subsynoviale in the middle section of the joint capsule and weight classes (

p > 0.005). In all weight classes except for the heaviest (>45 kg), the stratum subsynoviale was predominantly absent in the middle section of the stifle joint capsule. In the lowest weight class (0–5 kg), this layer was absent in 74.07% of cases (

n = 20), while in the next heavier class (5–10 kg), it was absent in 84.21% (

n = 16). In the heavier weight classes, the ratio of absence to presence of the middle stratum subsynoviale changed to 2:1 for the 10–15 kg class and 7:1 for the 15–20 kg class. For the weight classes of 25–30 kg, 30–35 kg, and 35–40 kg, there was only one case in each class, with the middle stratum subsynoviale absent in all three instances. In the 40–45 kg weight class, the ratio of absence to presence of the middle stratum subsynoviale was again confirmed at 3:1 (

Supplementary Figure S7).

3.7.4. Correlation Between Disease and Absence of the Stratum Subsynoviale in the Middle Section

A direct connection between the synovial layer and the fibrous layer in the middle section of the stifle joint capsule was observed in 81.36% (

n = 44) of cases with PL and 63.64% (

n = 7) of cases with CCLR. The condition of patellar luxation is significantly more frequently associated with the absence of the subsynovial layer compared to other diseases (

p = 0.001) (

Figure 12). Conversely, the subsynovial layer was present between the synovial and fibrous layers in only 18.64% (

n = 11) of cases with PL and 36.36% (

n = 4) of those with CCLR. In the group with both patellar luxation and cruciate ligament rupture, as well as in the control group, 50% of cases lacked a middle subsynovial layer.

3.7.5. Correlation Between Absence of the Stratum Subsynoviale in the Middle Section and Duration of Lameness

In every stage of the examined lameness cases, significantly more instances without a middle subsynovial layer were recorded than those with this layer present. In cases of chronic-progressive lameness, the number of cases was highest in all groups with 23 cases (88.46%) (

Supplementary Figure S8). Thus, cases with a chronic-progressive course were significantly more frequently associated with the absence of the middle subsynovial layer than other progression forms (

p-value = 0.001). In cases of acute lameness, this value was 85.71% (

n = 6), whereas in cases of peracute and subacute lameness, it was 62.50% (

n = 5 each). The group of subchronic lameness consisted exclusively of cases without this layer (

n = 7, 100%). In the control group dogs, which were not presented due to lameness, the middle subsynovial layer was present in all cases.

3.8. Correlation of Thickness Among the Proximal, Middle, and Distal Sections of the Stifle Joint Capsule

The thicknesses of the three sections of the stifle joint capsule—proximal, middle, and distal—show a significant correlation with one another. A linear relationship among the four breed groups is illustrated in

Supplementary Figure S9. The Spearman correlation coefficients range from 0.327 to 0.536, indicating a strong correlation with a

p-value of 0.001.

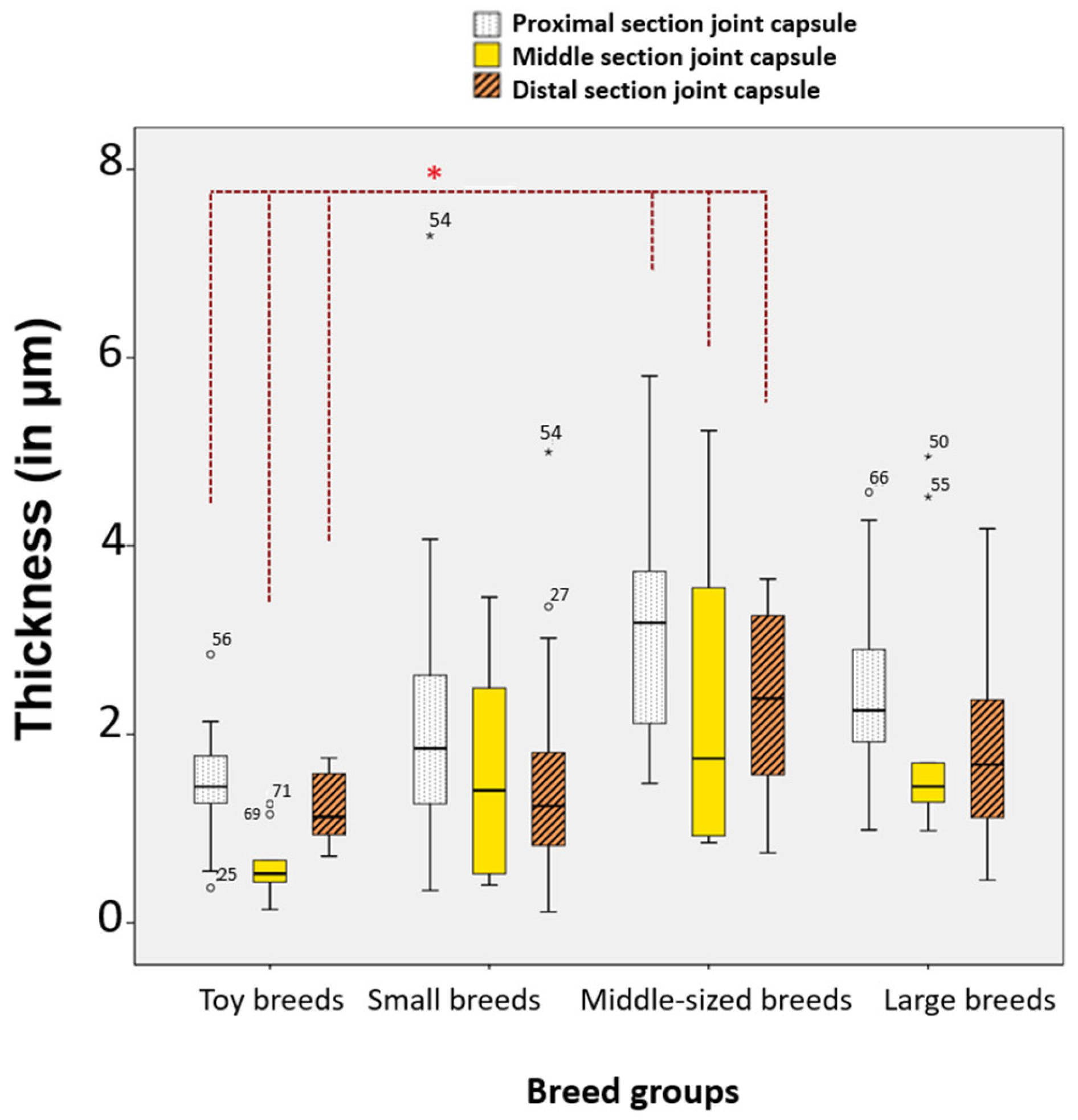

3.9. Correlation Between Breed Groups and Thickness of the Proximal, Middle, and Distal Sections of the Stifle Joint Capsule

Non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests for independent samples revealed significant differences in the thickness of the proximal and middle sections of the stifle joint capsule in relation to breed groups:

In toy dogs (

n = 15), the average thickness (in μm) of the proximal section (1714.97 ± 914.47) was 46.41% smaller than in large dogs (

n = 10) (

p = 0.045, Bonferroni). It was also 44.60% smaller than in medium-sized dogs (

n = 19) (3095.42 ± 1318.84) (

p = 0.036, Bonferroni) (

Figure 13).

Toy dogs had a significantly thinner middle section stifle joint capsule compared to all other breed groups. This data suggests that the size of the dog (toy, medium, large) significantly affects the thickness of the stifle joint capsule, particularly in the proximal and middle sections. Toy breeds tend to have thinner joint capsules compared to larger breeds.

Significant differences in thickness were observed among the four breed groups (

Supplementary Table S8). Toy dogs exhibited significantly thinner layers in the proximal, middle, and distal sections of the stratum fibrosum compared to medium-sized dogs, with percentage differences of 42.70%, 68.03%, and 49.02%, respectively. The

p-values indicate statistical significance (0.049, 0.006, and 0.048). In the proximal section of the stratum subsynoviale, both toy dogs and small dogs were found to be 66.85% and 65.73% thinner, respectively, when compared to large dogs (

p-values of 0.002 and 0.001). The middle section of the stratum synoviale also showed significant thinning in toy dogs (63.96% thinner) compared to large dogs (

p = 0.009), and in medium-sized dogs compared to large dogs (53.76% thinner,

p = 0.021). Overall, these results suggest that smaller dog breeds tend to have significantly thinner tissue layers compared to larger breeds across various sections.

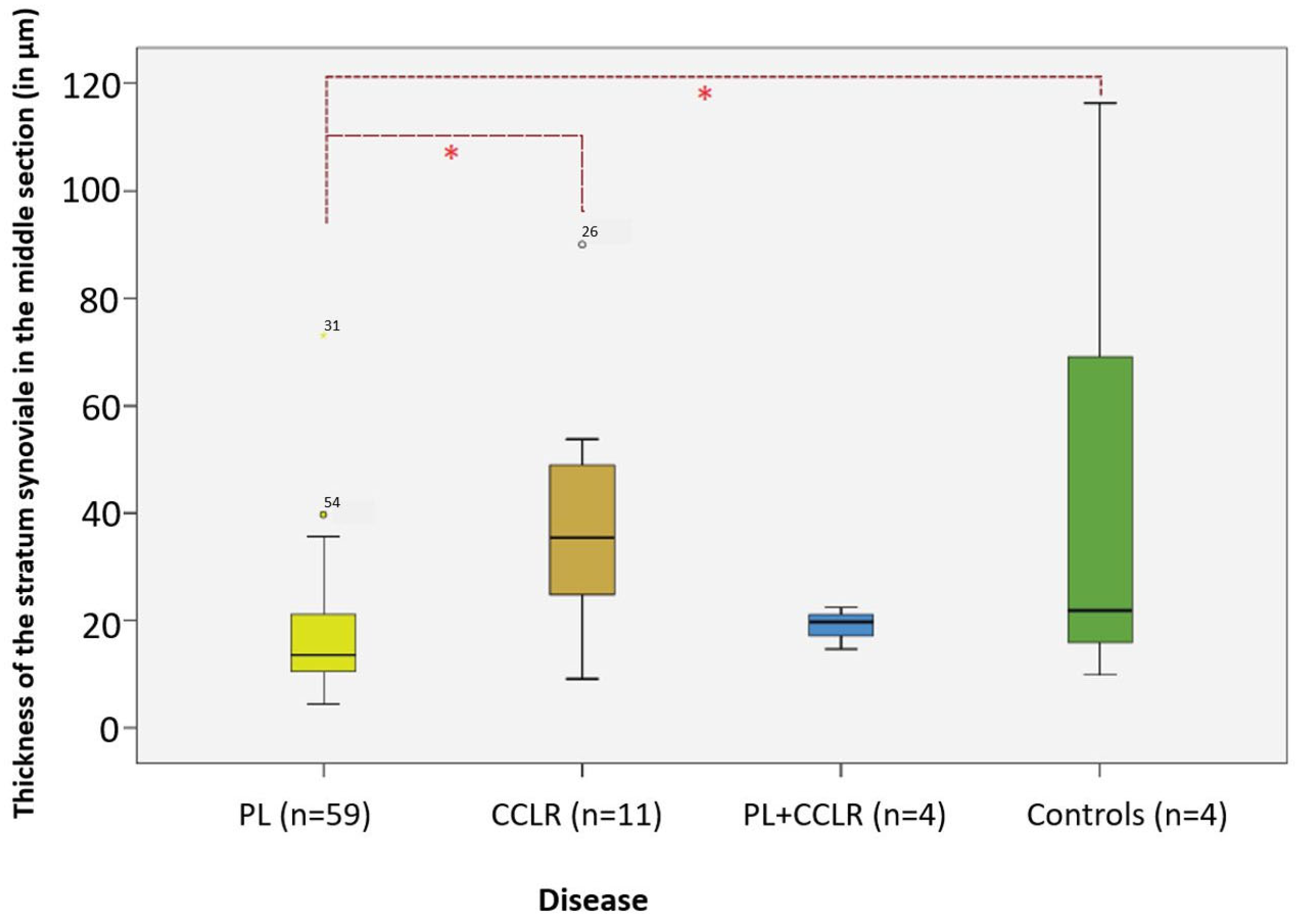

3.10. Correlation Between Disease and Thickness of the Stratum Synoviale

Significant differences in thickness were observed exclusively in the middle section of the stratum synoviale with respect to the different types of diseases (

Figure 14). Dogs with patellar luxation exhibited a significantly thinner middle section compared to those with cruciate ligament rupture and the control group. Specifically, dogs with PL (

n = 59) had a middle section that was 55.17% thinner than that of dogs with CCLR (

n = 11) (

p = 0.009, Bonferroni). Additionally, when compared to the controls (

n = 4), dogs with PL had a middle section that was 64.65% thinner (

p = 0.021, Bonferroni).

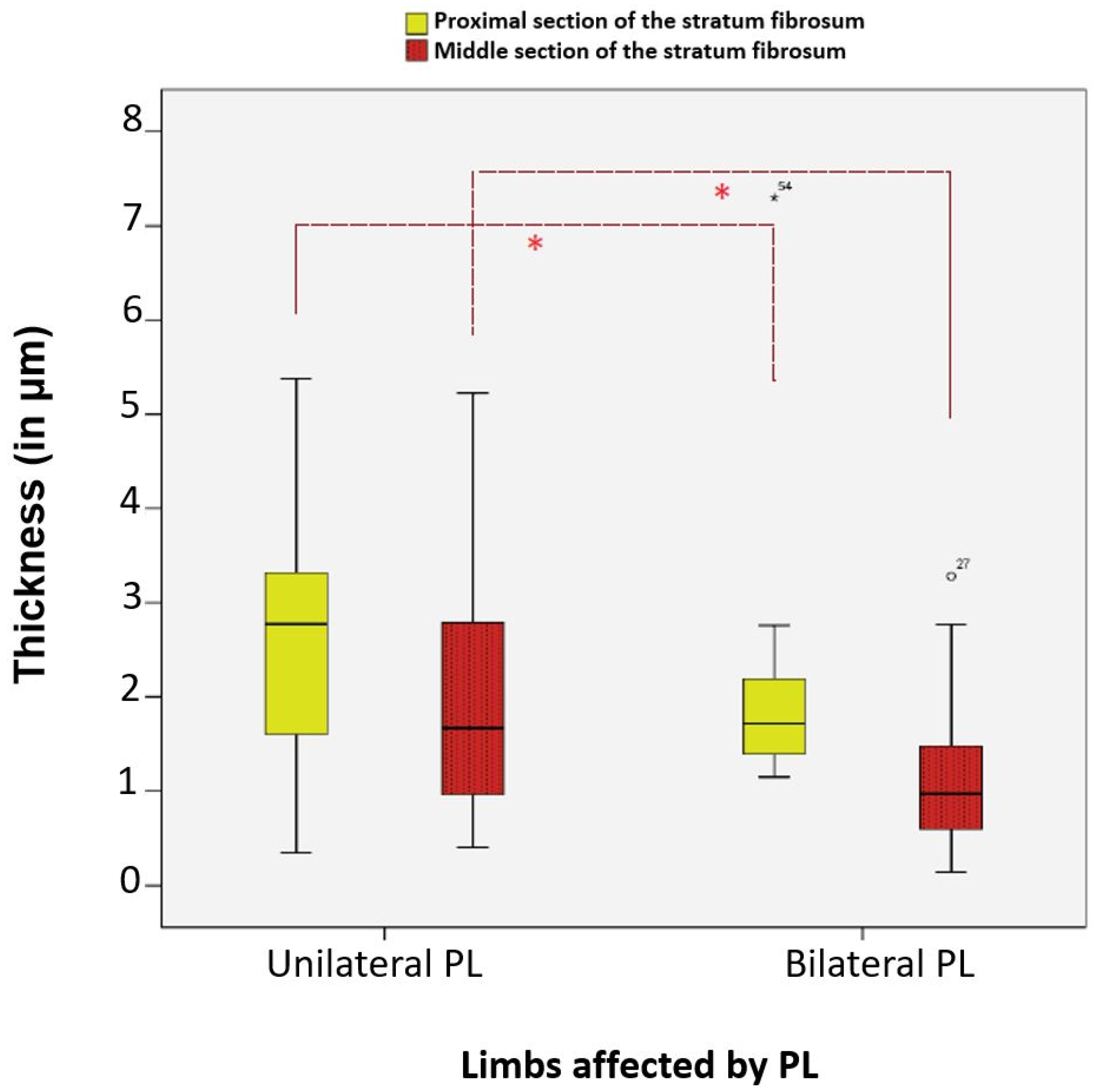

3.11. Comparison of Proximal and Middle Sections of the Stratum Fibrosum and Distal Section of the Stratum Synoviale Thickness in Unilateral vs. Bilateral Patellar Luxation

The average thicknesses of the proximal and middle sections of the stratum fibrosum, as well as the distal section of the stratum synoviale, were significantly different between cases of unilateral and bilateral patellar luxation. All three layer sections were significantly thinner in cases of bilateral patellar luxation (n = 31) compared to those with unilateral patellar luxation (n = 28).

Regarding the stratum fibrosum, it was, on average, 23.00% thinner in the proximal section (

p-value = 0.013, Mann–Whitney U) and 45.13% thinner in the middle section (

p-value = 0.017, Mann–Whitney U) in cases of bilateral patellar luxation compared to unilateral patellar luxation (

Figure 15).

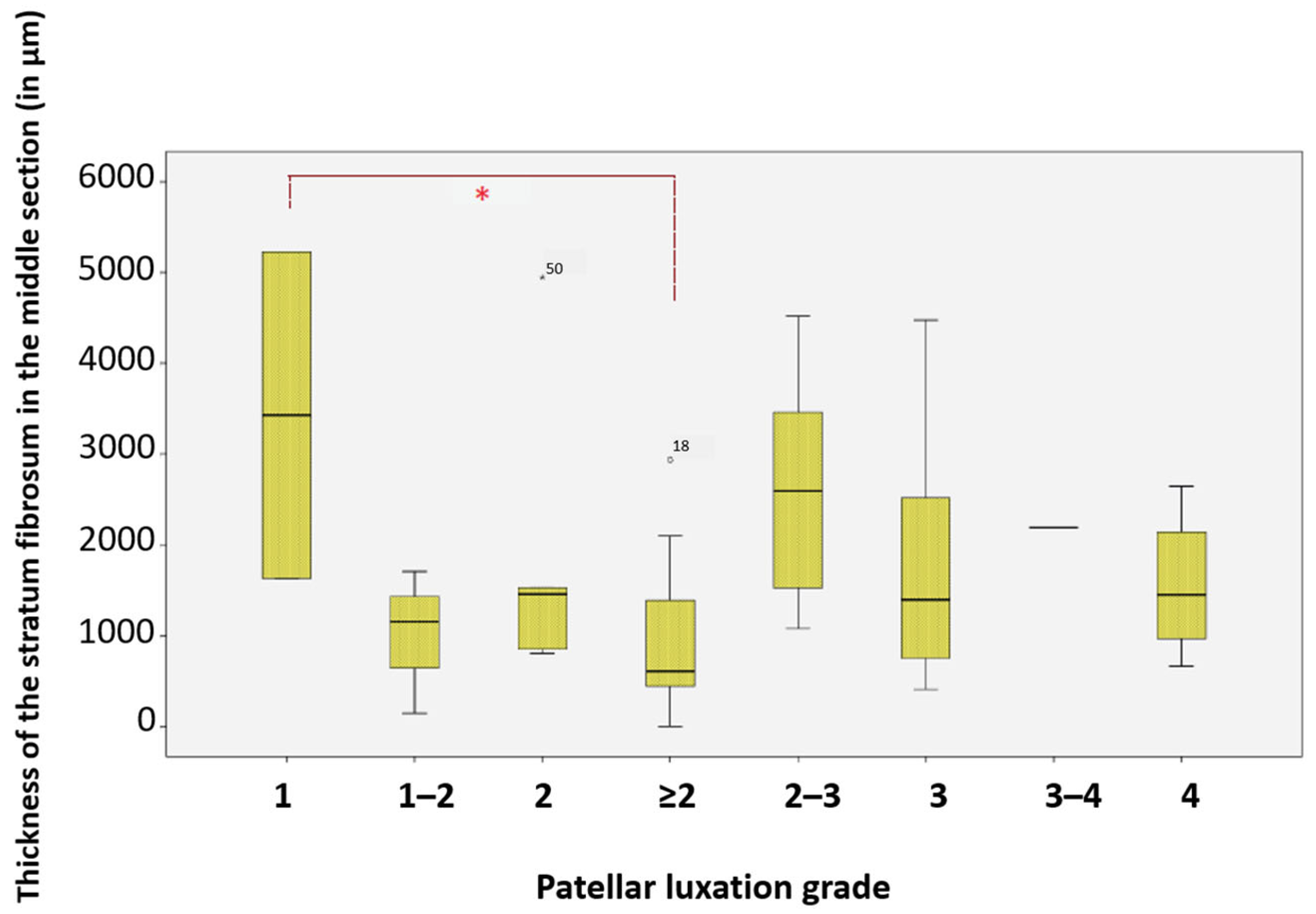

3.12. Middle Section of the Stratum Fibrosum and Patellar Luxation Grades

Significant differences were found in the average thickness of the middle section of the stratum fibrosum between dogs with patellar luxation grade 1 (

n = 2) and those with grade 2 or higher (

n = 20). The middle section was, on average, 71.92% thinner in dogs with more severe grades of patellar luxation compared to those with grade 1 (

p = 0.036, Gabriel) (

Figure 16).

3.13. Distal Section of the Stratum Subsynoviale and Degree of Villous Formation on the Inner Joint Surface

Cases without villi on the inner joint surface show a significantly thinner stratum subsynoviale in the distal section compared to those with abundant villi (

p-value = 0.030, LSD). On average, this layer is 66.85% thinner in cases without villi (

n = 3) than in those with numerous or prominent villi (

n = 26) (

Supplementary Figure S10).

3.14. Extracellular Fibrin Deposits in the Stifle Joint Capsule Connective Tissue

The area proportions of extracellular fibrin deposits in the connective tissue of the stifle joint capsule showed neither significant differences nor correlations with breed groups, age, sex, weight, type of disease, duration of lameness or degree of villous formation. Out of 78 cases, 13 (16.66%) were free of fibrin deposits. This included 6 dogs with patellar luxation, 5 with cruciate ligament rupture, and 1 with both patellar luxation and cruciate ligament rupture.

When present, fibrin deposits could be found disseminated throughout all three layers and in the proximal, middle, and distal sections of the stifle joint capsule (

Figure 4). The area proportions of fibrin ranged from 0.01% to 29.85% of the total area of the stifle joint capsule specimen. In 82.22% of cases with fibrin deposits, the proportion was 10% or less; in 13.51% of cases, it ranged from 10% to 20%; and in 5.41% of cases, it fell between 20% and 30%.

4. Discussion

Congenital patellar luxation (PL) and cranial cruciate ligament rupture (CCLR) are common hereditary musculoskeletal disorders in dogs. Patellar luxation, usually medial, results from skeletal malformations and soft tissue abnormalities, including joint capsule laxity. CCLR is associated with factors like an excessive tibial plateau angle, obesity, age, breed predisposition, and ligament degeneration [

1,

2,

3,

4]. While skeletal changes in PL are well documented, the role of soft tissue structures, particularly the stifle joint capsule, remains insufficiently studied.

Human studies on connective tissue disorders, such as those associated with COL6A1 mutations [

15], suggest that similar mechanisms may also apply to dogs with PL. Congenital connective tissue disorders in dogs often mirror these human conditions [

15,

16] indicating a possible link between genetic predispositions and structural changes in the stifle joint capsule. However, it remains uncertain whether structural changes in the stifle joint capsule, including soft tissue laxity, represent primary defects driving PL or secondary adaptations resulting from skeletal malalignment and altered mechanical forces. Clarifying this relationship is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the pathophysiology of PL and CCLR.

To explore this further, our study analyzed the thickness of joint capsule layers, superficial cell density in the stratum synoviale, villous formation, and fibrin content. These findings provide valuable insight into the relationship between skeletal deformities, PL or CCLR, and the histological changes observed in the stifle joint capsule.

Recently, new anatomical structures have been identified, such as a novel layer of elastic fibers between the synovial and fibrous membranes in the human shoulder [

5]. These findings highlight the importance of reexamining the histomorphological characteristics of joint capsules. Consequently, the present study aims to reassess the structure of both healthy and affected canine stifle joint capsules, particularly in cases of PL and CCLR, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of their morphological differences.

Our study aims to fill a gap in current research by providing comprehensive data on stifle joint capsule thickness and associated histological changes in dogs with congenital patellar luxation and/or CCLR. By understanding these structural alterations, we hope to shed light on the etiology of these orthopedic diseases and inform breeding practices to reduce its prevalence in canine populations. The inclusion of dogs with distal femoral fractures as controls was based on the rationale that these patients required capsular imbrication, which involved the removal of a small portion of the joint capsule as part of their treatment. Additionally, distal femoral fractures are generally acute orthopedic conditions that are unlikely to have caused significant alterations to the joint capsule’s structural integrity, making these dogs suitable for comparison. The use of completely healthy individuals or those with unrelated health issues as controls is limited due to ethical considerations and the challenges associated with acquiring such samples (e.g., following euthanasia).

All PL patients included in this study exhibited medial patellar luxation, which is the most common form of patellar luxation, as demonstrated in previous studies [

3,

17,

18]. Consequently, lateral capsular imbrication was performed to tighten the joint capsule on the lateral side, also for CCLR cases. In terms of sample collection, the stifle joint, whether right or left, was routinely exposed laterally via a parapatellar approach [

12]. It is important to note that the tissue samples of the joint capsule were exclusively examined from the lateral parapatellar region for histomorphological analysis of texture and collagen patterns. This raises the possibility that the capsule may exhibit different structural characteristics medially, not only in terms of sections but also in its layering. Additionally, it is worth considering that laterally directed patellar luxations might exhibit different structural characteristics. In these cases, the lateral displacement of the patella could lead to elongation of the joint capsule medially rather than laterally.

This surgical technique enhances stifle joint stability by overlapping or suturing the lateral joint capsule to counteract the medial displacement of the patella [

12]. This condition results in significant lateral elongation of the joint capsule, particularly in grades 3 and 4, with a corresponding medial narrowing. These observations suggest potential structural differences between lateral and medial aspects of the joint capsule. This hypothesis is supported by research on other joints. For instance, Bey et al. [

19] demonstrated regional thickness variations in the human shoulder joint capsule. While not directly comparable, studies on other joints provide insights into potential capsular adaptations. Germscheid et al. [

20] observed increased myofibroblast presence in the anterior section of traumatized human elbow joint capsules compared to healthy tissue. Similarly, Hecht et al. [

21] reported increased alpha-actin expression from smooth muscle cells in sheep knee joint capsules, noting differential thermal effects between lateral and medial aspects after laser irradiation, which resulted in altered layer and collagen patterns. These findings collectively suggest that joint capsules may exhibit regional structural and cellular differences, which could be relevant to understanding the pathophysiology of patellar luxation in dogs.

In our study, the breeds most affected by PL among purebreds were Chihuahuas (15.39%), Yorkshire Terriers (8.97%), and West Highland White Terriers (5.13%). These findings are consistent with existing literature [

3,

18,

22], which indicates that congenital PL predominantly affects small breed dogs. In the CCLR group, affected toy and small breeds included one Chihuahua mix and one Shih Tzu, while medium-sized breeds consisted of a Tibetan Terrier, a Beagle, a Collie mix, and a mixed breed. Larger breeds in this group included Boxers (

n = 2), a Caucasian Ovcharka mix, a Leonberger, and a Great Dane. The PL + CCLR group comprised four individuals: a Yorkshire Terrier, a Maltese, a West Highland White Terrier, and a medium-sized mixed breed, suggesting that both small and medium-sized breeds can be predisposed to this combination of conditions [

3,

18,

22].

The average age of dogs with PL in this study was 4.22 years, which aligns with the findings of Isaka et al. and Wangdee et al. [

23,

24]. This suggests that PL is commonly diagnosed in relatively young dogs, highlighting the importance of early detection and intervention. Conversely, the average age of dogs with CCLR was 6 years, consistent with reports by Gatineau et al. and Thompson et al. [

25,

26]. This age difference may indicate that CCLR are more likely to occur as dogs age, possibly due to degenerative changes on the ligament over time [

3]. Among the small subset of patients (

n = 4) with both patellar luxation and cruciate ligament rupture, the average age was 7.8 years, mirroring the findings of Campbell et al. [

27] and closely aligning with the 7.38 years reported by Candela Andrade et al. [

3]. This overlap in age suggests that dogs with pre-existing PL may be at increased risk for developing additional joint issues, emphasizing the need for comprehensive management of these patients.

In terms of sex distribution, females were slightly more frequently affected by PL, comprising 54.24% (

n = 32) of cases compared to 45.76% (

n = 27) in males. This trend is consistent with previous studies [

1,

18,

21,

22,

28], although it contrasts with Singleton’s findings [

10]. The higher incidence of PL in females may be linked to estrogen’s role in cartilage cell proliferation, as suggested by Gustaffson and Priester [

22,

28]. However, it is essential to recognize that other studies have reported equal occurrences in both sexes, indicating that the relationship between sex and patellar luxation remains a topic of debate [

3]. Regarding CCLR, the distribution was relatively balanced, with six females and five males affected, including one neutered dog in each group, in line with previous literature [

3].

The superficial cell layer of the synovial stratum consists of two overlapping layers in healthy human joints [

29,

30]. Sagiroglu’s studies [

31] on 24 Kangal mixed breeds revealed age-dependent variations in the stifle joint capsule’s superficial cell layers. Specifically, young dogs (0–3 months) typically have 1–2 layers, while dogs between 3.5–6 months and older dogs (7 months to 6 years) exhibit 3–5 or 2–6 overlapping layers, respectively. Superficial cells are pleomorphic, varying in size, shape, number, and orientation, influenced by the adjacent subsynovial stratum [

30,

32]. These cells can differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondrocytes, identifiable by specific surface markers [

33]. Factors such as age, joint health, and location significantly affect superficial cell morphology [

30]. Bronner and Farach-Carson [

34] highlight the critical role of the surface cell layer in “controlling the environment of the joint,” while Moskalewski et al. [

29] suggest that due to the heterogeneous properties of these cells, the superficial cell layer should be regarded as an independent organ, distinct from the fiber-rich joint capsule.

These characteristics are reflected in the variable numbers of superficial cell layers observed in this study. On average, 3 to 4 layers were present in the proximal and distal sections, while the middle section often exhibited a single layer. In 73.08% (

n = 57) of cases, at least one section (proximal, middle, or distal) had a multilayered superficial cell layer with a minimum of 3 layers. Wondratschek [

35] reported similar findings, noting that 50% of dogs with stifle osteoarthritis had multilayered superficial cell layers. Among the dogs in this study, those with chronic-progressive conditions (lameness duration > 90 days) had the most superficial cell layers, particularly in cases of concurrent patellar luxation and cruciate ligament rupture. Dogs PL had approximately a similar number of superficial cell layers as those with CCLR. In contrast, control dogs with the shortest duration of lameness (no lameness to 1–2 days) exhibited the fewest layers, which aligns with findings from Manunta et al. [

36]. In their research, Manunta et al. [

36] observed that in human athletes, an increase in multilayering of the surface cell layer was associated with hyperplasia, exudative characteristics, and infiltration by inflammatory cells. This suggests that the response of the surface cell layer may vary depending on the underlying condition and duration of lameness, indicating a potential link between joint health and the cellular response in both dogs and humans. This similarity between PL and CCLR cases likely reflects the influence of chronic joint instability rather than the degree of radiographic osteoarthritis. Even though PL is often considered less degenerative, prolonged abnormal loading and repetitive soft-tissue strain can still create enough synovial irritation to elicit a hyperplastic response comparable to that seen in CCLR.

The degree of villus formation on the inner joint surface was assessed using the surface enlargement factor (SEF), with higher values indicating larger or more numerous villi in the joint capsule samples. Dogs with PL exhibited the greatest variations in villus formation (1.00–4.94), while all control animals exhibited predominantly high or numerous villi (2.64–4.86), resulting in a mean value of 3.54 that significantly differed from the chronic joint pathologies (2.46). This variability in SEF values, particularly in dogs with PL, may be influenced by chronic synovial effusion. Chronic capsular distention caused by persistent effusion could stimulate villus formation, contributing to the histological changes observed in this study. In contrast, the narrower SEF range observed in dogs with CCLR (1.00–3.82) likely reflects the acute nature of the condition, which minimizes chronic remodeling of the joint capsule. Comparable patterns of synovial villus behavior have also been described in other species, including humans and horses, where chronic joint instability leads to progressive synovial surface remodeling [

30,

37]. These findings underscore the pivotal role that the chronicity of joint instability plays in villus development, emphasizing the importance of future research on this relationship.

Bertone’s [

37] results showed that chronic joint diseases lead to increasingly blunt and shorter synovial villi, often taking on a club-shaped appearance due to reperfusion-induced ischemia and resultant hypoxia, particularly affecting the tips of the villi. Other observations have been reported in dogs with CCLR, where synovial villi ranged from filamentous to club-shaped, contributing to the hyperplastic transformation of the inner joint capsule surface [

38]. Wondratschek [

35] also described the diversity of synovial villi in dogs with osteoarthritic changes, reporting that 96% exhibited villous hyperplasia with a wide range of shapes and sizes, sometimes even within a single sample. Our study confirmed that small-breed dogs exhibited significant variation in villus formation, with some displaying the largest villi while others had none. Notably, cases without villi had a significantly thinner distal subsynovial stratum compared to those with abundant villi, suggesting a possible relationship between subsynovial structure and villus development. Comparable patterns of synovial surface remodeling have also been described in humans, where chronic joint disease and mechanical irritation lead to alterations in villous morphology as well as changes in the synovial lining and subsynovial connective tissue [

30]. These results warrant further investigation into the role of chronicity in villous development within the joint capsule.

The absence of the stratum subsynoviale has not been explicitly documented in the existing literature. However, in 59 out of 78 cases (75.64%), the stratum subsynoviale in the middle section of the stifle joint was undetectable, representing a significant finding. In these cases, the stratum synoviale directly adjoined the stratum fibrosum, while all three layers were detectable in the proximal and distal sections of the same sample. Notably, dogs with PL were significantly more likely to lack the stratum subsynoviale in the middle section, with 81.36% (n = 44) affected, compared to 63.64% (n = 7) of dogs with CCLR.

The absence of the stratum subsynoviale was significantly associated with the duration of lameness; in chronic-progressive cases (lameness duration > 90 days), 88.46% (

n = 23) of the dogs were affected, indicating a stronger correlation with longer lameness durations. While the stratum fibrosum is typically regarded as the primary layer contributing to the mechanical stability of the joint capsule, the stratum subsynoviale may play an indirect but important role in maintaining tissue integrity. This layer provides structural support to the overlying stratum synoviale and facilitates nutrient transport, cellular turnover, and vascularization, which are essential for synovial function and joint health. Its absence in the middle section may impair these processes, potentially leading to degenerative changes in the synovial layer and reduced adaptability of the joint capsule to mechanical forces. This raises the question of whether the stratum subsynoviale in these 59 cases with PL may have existed previously but underwent changes that rendered it indistinguishable from the adjacent stratum fibrosum. Chronic synovial effusion and prolonged joint instability, common in PL, could contribute to fibrotic remodeling and a loss of clear demarcation between these layers, as the tissue adapts to abnormal loading conditions. Notably, some recent literature does not acknowledge the stratum subsynoviale, suggesting that the joint capsule consists solely of an inner stratum synoviale and an outer stratum fibrosum [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43].

Thickness measurements in this study revealed significant variation in the stifle joint capsule across the proximal, middle, and distal sections, with these measurements showing strong correlation with one another. This aligns with the findings of Bey et al. and Wagner et al. [

19,

40], who highlighted regional variations in joint capsule thickness as adaptations to loading conditions. The joint capsule, functioning as a limiting structure for synovial joint motion, undergoes continuous histomorphological remodeling in response to mechanical loads. Ralphs and Benjamin [

44] noted that the joint capsule thickens at its bony attachments, which was corroborated here, as the proximal section was thicker than the middle section in 93.60% (

n = 73) of cases.

In this study, we observed that dogs with PL had a significantly thinner synovial layer in the middle section, reduced by 55.17% to 64.65% compared to the other groups (CCLR and controls, respectively). This variation may be influenced by the functional demands and mechanical adaptations of the joint. It is well known that the joint capsule thickness increases near its attachment sites, where it contains more vessels, fat cells, and synovial lining compared to the midsection. The thinner layers in dogs with PL may reflect reduced mechanical loading or functional disruption in these regions. Bilateral PL may also contribute to these microscopic changes, as it has been associated with thinner fibrous layers in the proximal and middle regions, as well as a thinner synovial layer in the distal region, compared to unilateral cases. This suggests that weight shifting to the healthy limb in unilateral luxation could mitigate joint capsule changes.

For dogs with CCLR, the increased synovial thickness observed could result from proliferative lymphoplasmacellular synovitis, consistent with previous studies [

14,

38,

45]. In femur fracture cases within the control group, instability in the adjacent stifle joint may contribute to synovitis and subsequent thickening. These findings highlight the importance of accounting for regional variations in capsule thickness, of luxation, and normal synovial plication when interpreting joint capsule histomorphology. Higher grades of PL and associated capsule changes underscore the complex interplay between functional disruption, loading conditions, and compensatory mechanisms.

Significant differences in joint capsule thickness were observed among breed groups, with toy dogs showing a thinner proximal section compared to medium and large breeds, and a thinner middle section relative to all other groups.

Analysis of extracellular fibrin deposits in the stifle joint capsule revealed no significant differences or correlations with breed, age, sex, weight, type of disease, duration of lameness, or degree of villous formation. This suggests that fibrin presence may reflect a generalized response within the joint capsule, rather than being tied to specific individual characteristics or conditions. Insights from Oberbauer et al. [

16] and Hildebrandt et al. [

6] indicate that genetic factors and trauma responses may collectively shape the histopathological landscape of the joint capsule in conditions like PL and CCLR. Further research could explore the implications of these fibrin deposits in relation to joint function and recovery, particularly in the context of surgical interventions.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, the absence of immunohistochemical staining to analyze collagen patterns within the stifle joint capsule is a significant limitation. Elastic fibers and specific collagen subtypes are critical for joint stability and mechanical adaptation, and their distribution and structural organization remain unexplored in this study. Future research incorporating immunohistochemical techniques could provide valuable insights into collagen patterns, particularly in dogs with patellar luxation compared to unaffected dogs. Additionally, biomechanical analyses to assess differences in the mechanical properties of collagen fibers between affected and unaffected dogs would complement histological findings and enhance our understanding of joint capsule adaptations.

A further limitation of this study concerns the grading of patellar luxation. Several cases received different grades when evaluated by different veterinarians, and these animals were therefore assigned to an intermediate category. Although this approach reduced inter-observer discrepancies, it may still have affected the ability to detect clear grade-specific histological differences. Future studies that incorporate detailed assessments of structural changes in the surrounding hard tissues—such as femoral trochlear morphology, tibial alignment, or rotational deformities—could help define the patellar luxation grade more precisely. Integrating these objective skeletal parameters may reduce grading ambiguity and, in turn, minimize the dilution of histological distinctions between severity categories.

Control samples were obtained from dogs with distal femoral fractures or from dogs euthanized for unrelated health conditions, with owner consent. Obtaining completely healthy stifle joint capsules is ethically challenging, as owners are generally reluctant to allow tissue collection after euthanasia. Ideally, future studies should include samples from truly healthy dogs—and, where possible, from animals within a comparable age range—to establish a more accurate baseline. However, these ethical and practical constraints make such sampling difficult. In this context, collaboration with other institutions may help increase access to suitable and better-matched control material. These limitations underscore the need for further research to address these gaps and build upon the findings of the present study.