Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomic Analysis of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus NSP9 Protein with Host Proteins

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells and Viruses

2.2. Antibodies and Reagents

2.3. Plasmid Construction and Transfection

2.4. Western Blotting

2.5. Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

2.6. LC–MS/MS Analysis

2.7. Bioinformatics

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

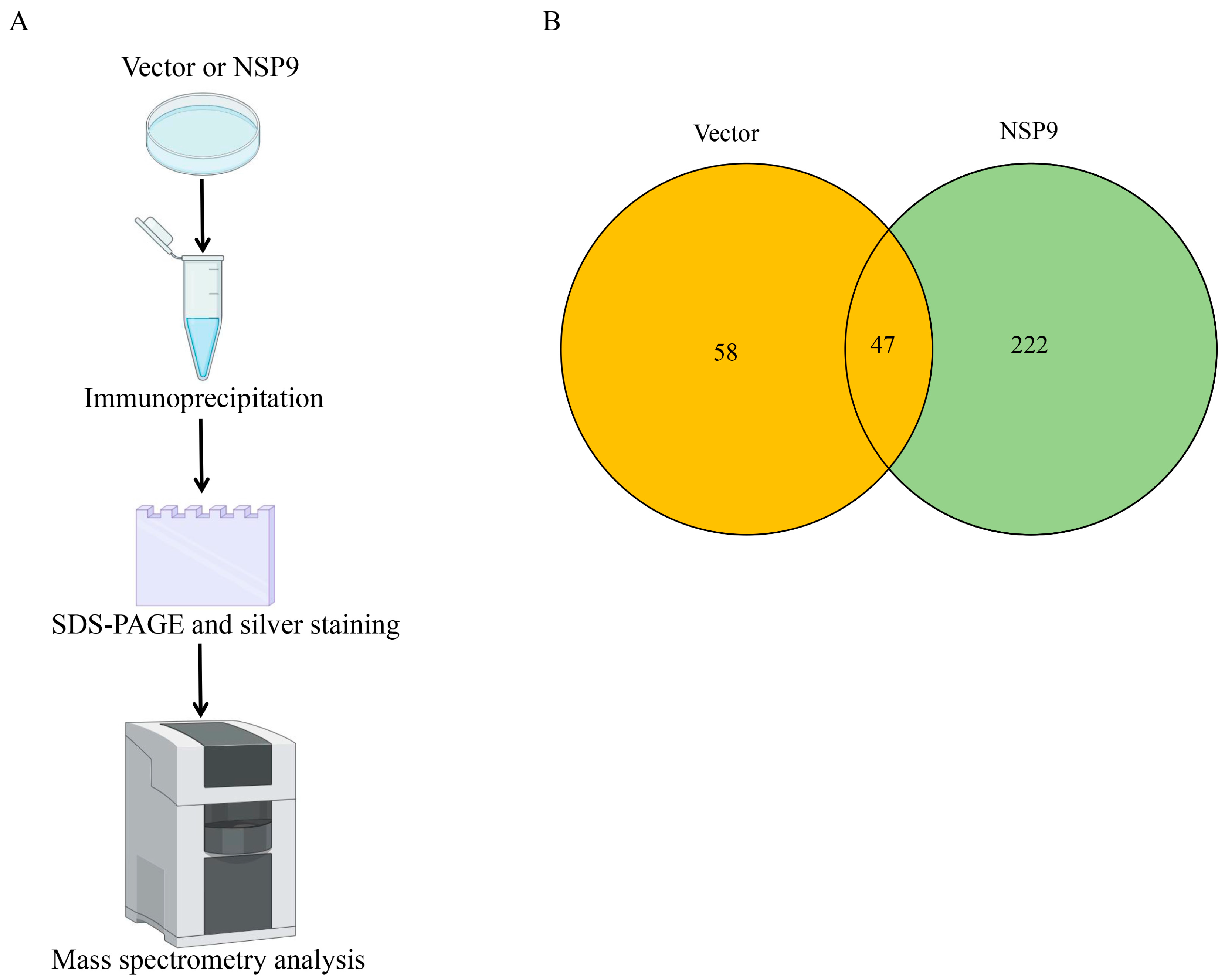

3.1. Identification of Host Protein Interacting with PRRSV NSP9 by Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry

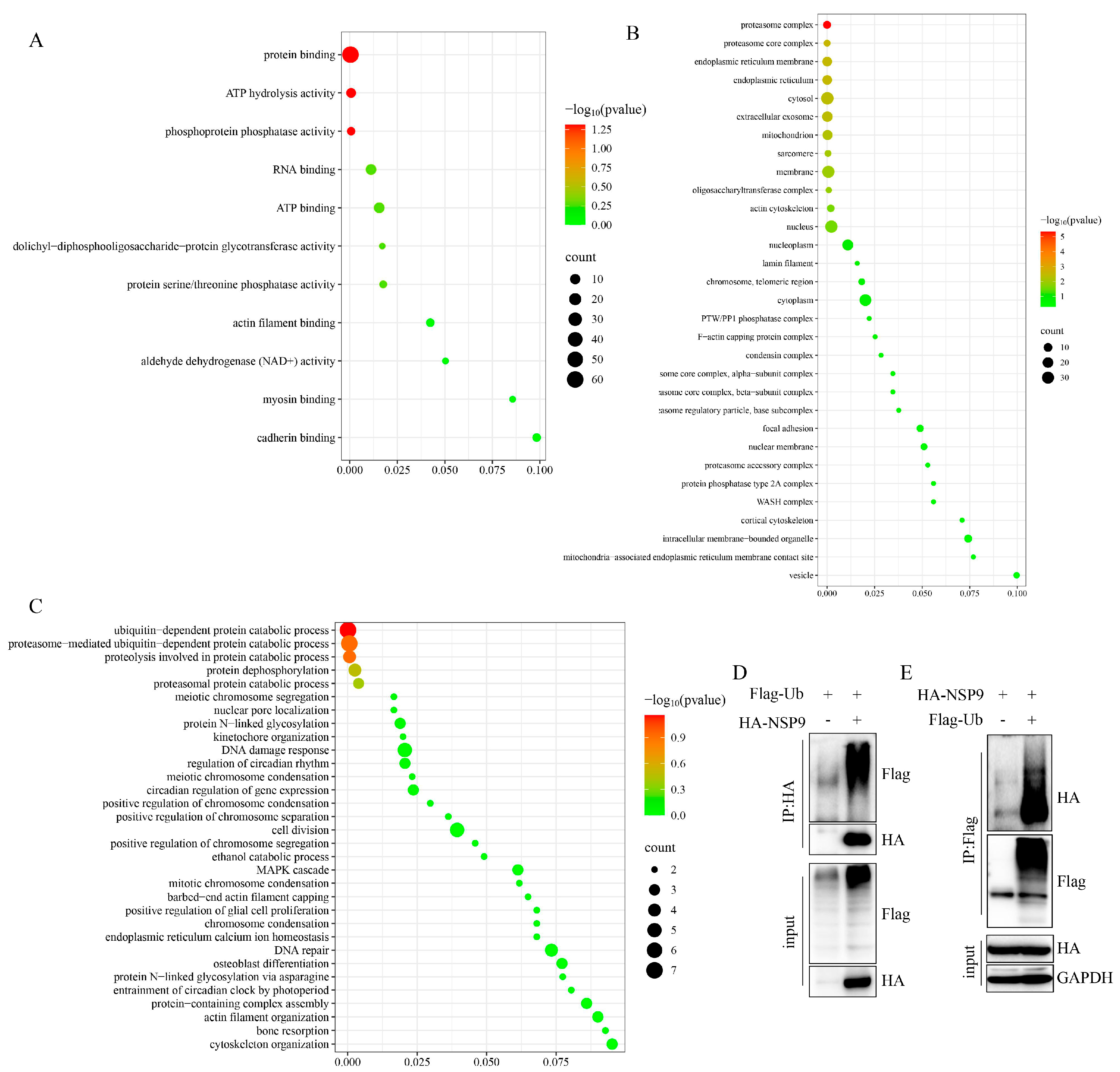

3.2. Functional Characterization of NSP9-Interacting Proteins Reveals a Role in Post-Translational Modifications

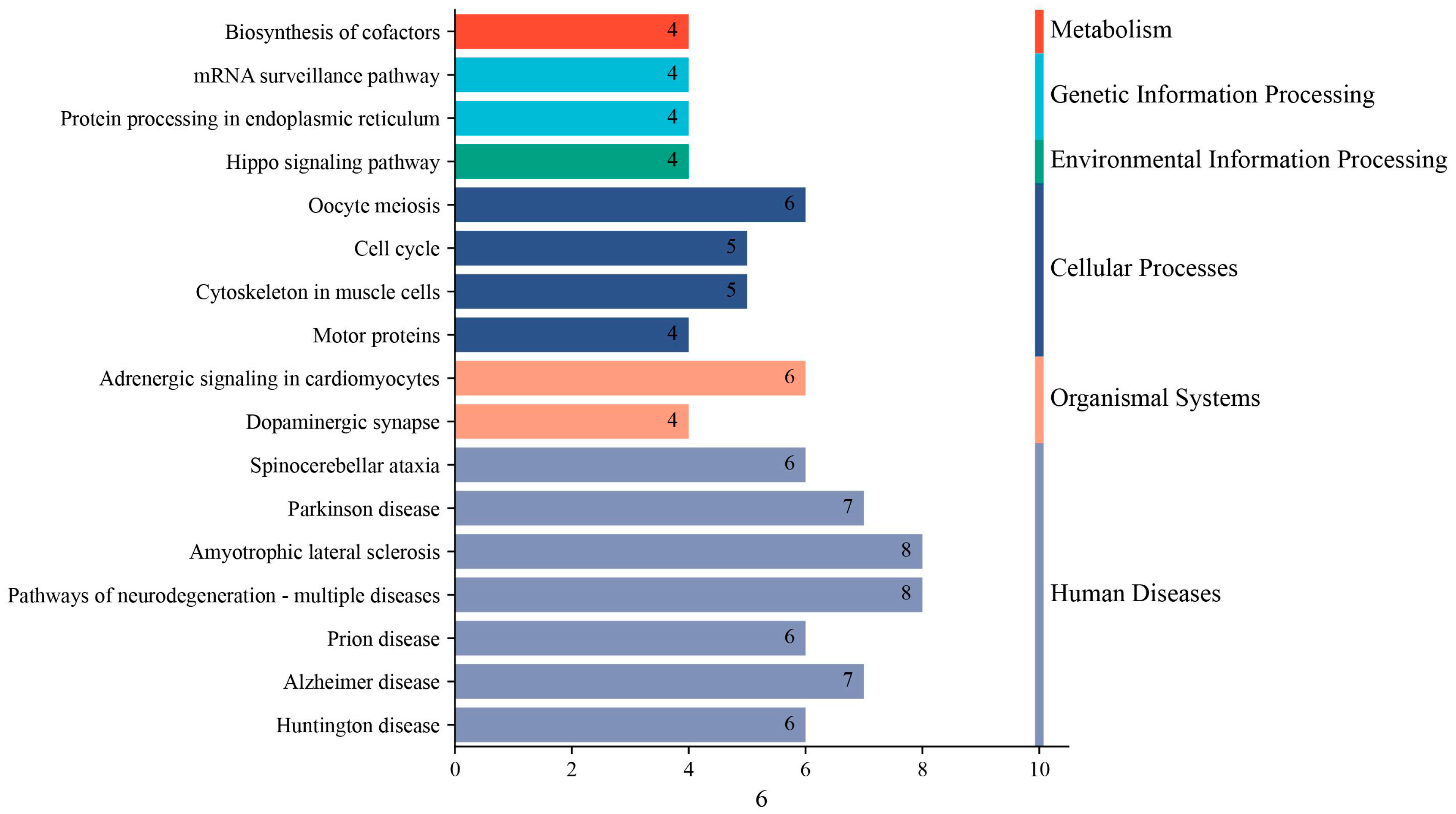

3.3. KEGG Pathway Annotation of Host Proteins Interacting with PRRSV NSP9

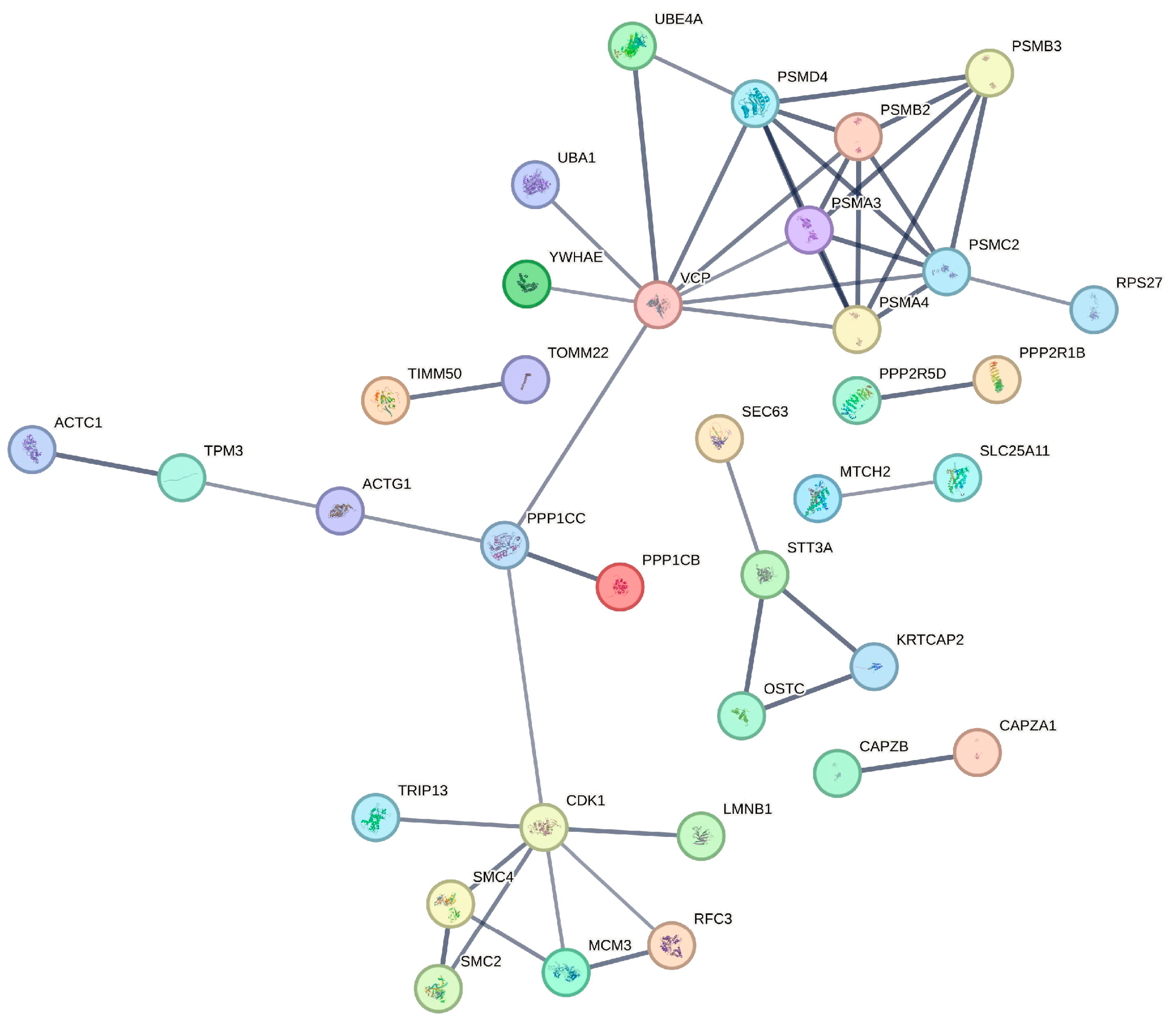

3.4. Protein-Protein Interaction Network of NSP9-Associated Host Proteins

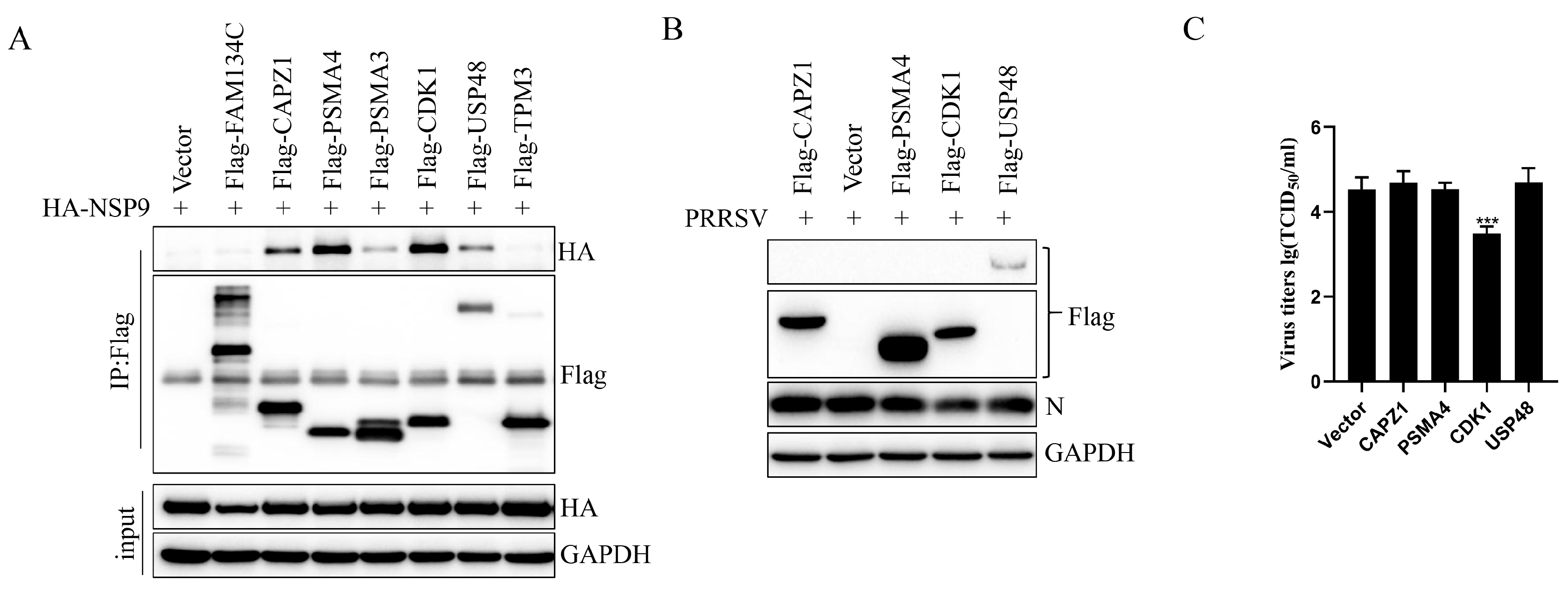

3.5. CDK1 Expression Inhibited PRRSV Replication

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Neumann, E.J.; Kliebenstein, J.B.; Johnson, C.D.; Mabry, J.W.; Bush, E.J.; Seitzinger, A.H.; Green, A.L.; Zimmerman, J.J. Assessment of the economic impact of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome on swine production in the United States. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2005, 227, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albina, E. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome: Ten years of experience (1986–1996) with this undesirable viral infection. Vet. Res. 1997, 28, 305–352. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lunney, J.K.; Fang, Y.; Ladinig, A.; Chen, N.; Li, Y.; Rowland, B.; Renukaradhya, G.J. Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus (PRRSV): Pathogenesis and Interaction with the Immune System. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2016, 4, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Xu, H.; An, T.; Cai, X.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, H. Recent Progress in Studies of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus 1 in China. Viruses 2023, 15, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimman, T.G.; Cornelissen, L.A.; Moormann, R.J.; Rebel, J.M.; Stockhofe-Zurwieden, N. Challenges for porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) vaccinology. Vaccine 2009, 27, 3704–3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Feng, W.H. Regulation and evasion of antiviral immune responses by porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virus. Res. 2015, 202, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Feng, W.H. Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus Evades Antiviral Innate Immunity via MicroRNAs Regulation. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 804264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Ma, L.; Yang, M.; Wu, W.; Feng, W.; Chen, Z. The Function of the PRRSV-Host Interactions and Their Effects on Viral Replication and Propagation in Antiviral Strategies. Vaccines 2021, 9, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Y.; Wu, C.; Gu, G.; Sun, W.; Zhang, Y.J.; Zhou, E.M. Improved Vaccine against PRRSV: Current Progress and Future Perspective. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brar, M.S.; Shi, M.; Hui, R.K.; Leung, F.C. Genomic evolution of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) isolates revealed by deep sequencing. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Music, N.; Gagnon, C.A. The role of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus structural and non-structural proteins in virus pathogenesis. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2010, 11, 135–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulyaeva, A.; Dunowska, M.; Hoogendoorn, E.; Giles, J.; Samborskiy, D.; Gorbalenya, A.E. Domain Organization and Evolution of the Highly Divergent 5’ Coding Region of Genomes of Arteriviruses, Including the Novel Possum Nidovirus. J. Virol. 2017, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Treffers, E.E.; Li, Y.; Tas, A.; Sun, Z.; van der Meer, Y.; de Ru, A.H.; van Veelen, P.A.; Atkins, J.F.; Snijder, E.J.; et al. Efficient-2 frameshifting by mammalian ribosomes to synthesize an additional arterivirus protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E2920–E2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dokland, T. The structural biology of PRRSV. Virus. Res. 2010, 154, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Fan, B.; Bai, J.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Jiang, P. The N-N non-covalent domain of the nucleocapsid protein of type 2 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus enhances induction of IL-10 expression. J. Gen. Virol. 2015, 96, 1276–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Perlman, S. Unraveling the complexities of neurotropic virus infection and immune evasion. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2025, 89, e0018523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, H.H.; Schneider, W.M.; Rice, C.M. Interferons and viruses: An evolutionary arms race of molecular interactions. Trends Immunol. 2015, 36, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Li, F.; Li, W.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, P.; Chen, J. Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomic Analysis of Potential Host Proteins Interacting with N in PRRSV-Infected PAMs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Tian, J.; Nan, H.; Tian, M.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Huang, B.; Zhou, E.; Hiscox, J.A.; Chen, H. Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus Nucleocapsid Protein Interacts with Nsp9 and Cellular DHX9 To Regulate Viral RNA Synthesis. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 5384–5398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Qiao, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Li, Z.; Ma, H.; Yang, L.; Ruan, H.; Weng, M.; et al. Structural Characterization of Non-structural Protein 9 Complexed With Specific Nanobody Pinpoints Two Important Residues Involved in Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus Replication. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 581856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, J.; Ge, X.; Zhou, R.; Zheng, H.; Geng, G.; Guo, X.; Yang, H. Nsp9 and Nsp10 contribute to the fatal virulence of highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus emerging in China. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K.; Gao, J.C.; Xiong, J.Y.; Guo, J.C.; Yang, Y.B.; Jiang, C.G.; Tang, Y.D.; Tian, Z.J.; Cai, X.H.; Tong, G.Z.; et al. Two Residues in NSP9 Contribute to the Enhanced Replication and Pathogenicity of Highly Pathogenic Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus. J. Virol. 2018, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, H.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhao, M.; Wang, N. Research Progress on the NSP9 Protein of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 872205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Zhang, N.; Ge, X.; Zhou, L.; Guo, X.; Yang, H. The interaction of nonstructural protein 9 with retinoblastoma protein benefits the replication of genotype 2 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in vitro. Virology 2014, 464, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, X.; Cao, L.; Xu, T.; Zhao, L.; Huang, K.; Zou, Z.; Ren, P.; Mao, H.; Yang, Y.; Gao, S.; et al. PSMD12-Mediated M1 Ubiquitination of Influenza A Virus at K102 Regulates Viral Replication. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0078622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, W.C.; Yu, W.Y.; Huang, S.H.; Lai, M.M.C. Ubiquitination of the Cytoplasmic Domain of Influenza A Virus M2 Protein Is Crucial for Production of Infectious Virus Particles. J. Virol. 2018, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wen, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Z.; Li, X. Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomic Analysis of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus NSP9 Protein with Host Proteins. Animals 2025, 15, 3520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243520

Wen W, Liu Y, Wang W, Zhu Z, Li X. Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomic Analysis of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus NSP9 Protein with Host Proteins. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243520

Chicago/Turabian StyleWen, Wei, Yuhang Liu, Wenqiang Wang, Zhenbang Zhu, and Xiangdong Li. 2025. "Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomic Analysis of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus NSP9 Protein with Host Proteins" Animals 15, no. 24: 3520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243520

APA StyleWen, W., Liu, Y., Wang, W., Zhu, Z., & Li, X. (2025). Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomic Analysis of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus NSP9 Protein with Host Proteins. Animals, 15(24), 3520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243520