1. Introduction

Altering feeding frequency has emerged as a particularly effective approach towards improved growth traits and meat quality of pigs [

1]. However, contradictory findings have been reported regarding the effects of higher or lower feeding frequency on growth-related phenotypes of pigs. Some studies have indicated that increasing feeding frequency could improve nutrient utilization efficiency in swine [

2,

3], while others have demonstrated that lower feeding frequency might enhance feed efficiency of swine compared to ad libitum [

4,

5]. Despite this, higher or lower feeding frequency impacted the growth performance of pigs associated with changes in energy metabolism, indicating that altered feeding frequency could decrease fat deposition or promote muscle accretion of pigs.

Dietary energy density as a determinant factor in regulating energy metabolism has been demonstrated to affect the growth-related traits and meat quality in meat-producing animals. The partition of energy into adipose or muscle tissues contributed to the feed efficiency of pigs [

6]. Insufficient dietary energy supply led to growth retardation and compromised myogenesis, while energy excess promoted meat quality deterioration in pigs [

7,

8]. In the practical feeding of Chinese indigenous pig breeds, restricted feeding frequency has been applied to control the fat deposition to achieve a better carcass composition and meat quality with a compromised growth rate. However, existing studies lacked evidences to define how precise dietary energy density adjustments could achieve a balance between growth rate and carcass composition/meat quality in pigs under the condition of restricted feeding frequency. Additionally, the effect of dietary energy density on energy partitioning of pigs that were offered restricted feeding allowance remains unknown.

Gut microbiota has been shown to play a key role in dietary energy-induced alterations of carcass composition in meat-producing animals [

9,

10]. Imbalanced gut microbiota has been associated with excessive lipid deposition [

11]. In addition, certain changes in taxa abundances have been correlated with whole-body fat content [

12,

13]. However, it is uncertain whether dietary energy level could shape the gut microbiota composition of pigs under the restricted feeding condition.

We hypothesized that the optimal dietary net energy would improve the carcass traits and meat quality of pigs that offered restricted feeding allowance. This study aimed to investigate the influence of dietary energy levels on the growth performance, carcass traits, meat quality, intramuscular lipid metabolism, and cecal microbiota composition of pigs under restricted feeding frequency conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment Design and Animal Management

A total of 32 healthy castrated male Sichuan-Tibetan black pigs with similar initial body weights (25.98 ± 0.27 kg) were randomly allocated into four groups. Each group had eight replicates of one pig per replicate pen. Diets were formulated to meet the feeding standards for Chinese local pig breeds (GB/T 39235-2020) [

14]. All diets were iso-nitrogenous, with identical crude protein content (

Table 1). Pigs in the CON group were provided with a basal diet (2330 kcal NE kg

−1) on an ad libitum basis, while pigs in the other three treatment groups received diets formulated to contain 2330, 2370, and 2410 kcal NE kg

−1, respectively, with twice-daily feeding at 8:00 and 18:00, and each feeding session lasting one hour. The ad libitum pigs had free access to feed throughout the trial. The temperature in the pig environment was maintained at 22–25 °C, and the relative humidity was maintained at 60–65%. In order to calculate average daily gain (ADG), average daily feed intake (ADFI), and feed to gain ratio (F/G), the initial body weight and final body weight were measured, and the consumption amount of feed for each pig was recorded on a weekly basis.

2.2. Sample Collection

The experiment lasted for 19 weeks. At the end of the feeding trial, after 8 h of fasting, all the experimental pigs were euthanized via electrical stunning and subsequently slaughtered. After removing the head, hooves, and tail, the carcass weight was measured, followed by splitting the carcass into two half-sides along the midline. The longissimus dorsi muscle (LDM) sample from the left side of the carcass was sealed in a plastic bag and stored at −80 °C for muscle chemical composition and fatty acid analysis. An additional sample of LDM was collected, placed into 1.5 mL EP tubes, and stored at −80 °C for gene expression analysis. LDM samples between the 10th and 13th ribs of the right carcass side were collected for meat quality analysis. The cecum was immediately separated, placed on ice, and punctured using sterilized surgical scissors to extract cecal contents, which were aliquoted into 1.5 mL EP tubes and stored at −80 °C for microbiota composition analysis.

2.3. Carcass Traits Measurements

Backfat thickness was determined using a digital caliper in accordance. Triplicate measurements were obtained at three standardized anatomical positions, including the first thoracic vertebra, the last thoracic vertebra, and the last lumbar vertebra on the left side of the carcass. The cross-sectional areas of the LDM were measured using a digital vernier caliper. The loin muscle area was calculated according to the following standardized formula:

2.4. Meat Quality Measurements

LDM samples were excised from the 10th–13th rib. Visible connective tissue and surface fat were meticulously removed using sterile surgical instruments, and samples were cut into small pieces and collected to evaluate the meat quality indexes, including the pH, color, cooking loss, and drip loss. Muscle pH was measured using the SFK-Technology pH meter (SFK LEBLANC, Kolding, Denmark). The meat color parameters, including L* (lightness), a* (redness), and b* (yellowness), were measured using the Minolta colorimeter (CR-400, Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan). Drip loss was measured as follows: a muscle sample from the 10th rib region was trimmed, weighed, and hung on a metal hook to be suspended in an inflatable plastic bag. After being stored at 4 °C for 48 h, the surface moisture of samples was removed by filter paper blotting prior to reweighing. For cooking loss analysis, LDM samples were vacuum-sealed in plastic bags and immersed in a water bath until the core temperature reached 70 °C. After cooling to ambient temperature, samples were reweighed. Both drip loss and cooking loss were calculated using the following unified formula [

15]:

2.5. Chemical Composition Analysis of Skeletal Muscle

The LDM sample was weighed and placed in a pre-labeled glass dish. Subsequently, it was transferred together with the glass dish into a freeze-dryer for the process of lyophilization under the following conditions: shelf temperature: −50 °C; condenser temperature: −80 °C; chamber pressure: <10 Pa for 48 h until constant weight. After moisture determination, the sample was crushed and sieved through a 40-mesh standard sieve and then was analyzed for EE (method 920.39) and CP (method 954.01) according to AOAC methods [

16].

2.6. Muscle Fatty Acid Composition Analysis

The analysis of fatty acid (FA) composition in LDM was carried out using a gas chromatograph (Agilent 7890A, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) [

17]. Initially, total lipids were extracted from the LDM. After homogenizing, the hexane layer was aspirated via anhydrous sodium sulfate for FA analysis. The temperature program was set as follows: the initial column temperature was maintained at 140 °C for 15 min, then increased at a rate of 3 °C per minute until reaching 240 °C, where it was held for another 15 min. The injector and detector temperatures were both set at 250 °C, while the inlet temperature was 220 °C. The injection volume was 1 μL, with a split ratio of 10:1. The gas flow rates were as follows: hydrogen at 30 mL/min, air at 400 mL/min, nitrogen at 40 mL/min, and the carrier gas at 0.8 mL/min. Individual FA peaks were identified by comparing their retention times with those of known standards (Sigma, Tokyo, Japan).

2.7. Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

The total RNA of the LDM was extracted using RNAiso Plus reagent (Takara, Beijing, China), and the concentration and purity of the total RNA were determined using the Yoke N6000 UV spectrophotometer (YOKE, Tokyo, Japan). Further reverse transcription of cDNA was performed using the Prime Script RT Reverse Transcription Kit (Takara, Chengdu, China). RT-qPCR was conducted using the CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). Each reaction mixture consisted of 5 μL TB Green Premix Ex Taq II, 0.5 μL forward primer (10 μM), 0.5 μL reverse primer (10 μM), 2 μL sterile water, and 2 μL cDNA template, with a total reaction volume of 10 μL. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation and enzyme activation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation/annealing/extension and data acquisition (95 °C for 30 s, annealing for 40 s at primer-specific temperatures), and a melt curve analysis from 65 °C to 90 °C with 0.5 °C increments every 5 s. The

ACTB gene was used as an internal reference for normalization, and relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2

−ΔΔCt method (

Table 2) [

18].

2.8. Cecal Microbiota Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from cecal contents using the QiaAmp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Beijing, China), with DNA quality subsequently verified through 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. The V3-V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified via PCR using the forward primer (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′) and the reverse primer (5′-CCGTCAATTCMTTTRAGTTT-3′). Amplicon libraries were prepared using the Ovation Rapid DR Multiplex System 1-96 (NuGEN, San Carlos, CA, USA), followed by paired-end sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) for 16S rRNA gene analysis. Raw sequence data were processed and analyzed using Mothur version 1.48.0 to generate amplicon sequence variants (ASV) abundance and taxonomic classification tables. To account for variations in sequencing depth across samples, sequence reads were normalized to the minimum sequencing depth through random subsampling. Subsequent microbial community analyses were performed using R Studio version 3.4.1 with the vegan and phyloseq packages for community ecology analyses.

2.9. Statistical Analyses

The results are presented as means ± standard errors of the mean (SEM). All experimental data were analyzed using ANOVA in SAS 9.4 statistical software. Linear and quadratic effects within the restricted feeding frequency group were evaluated using orthogonal polynomials comparison. The p-value less than 0.05 were considered statistically different.

4. Discussion

The feed to gain ratio of growing-finishing pigs largely depends on the dietary energy allocation to lean or fat tissues [

20]. Restricted feeding regimes have been adopted in practical pig production to decelerate fat deposition and promote lean deposition, thereby improving feeding efficiency [

21]. In the present study, the final body weight, ADG, and ADFI of restricted-fed pigs were significantly decreased compared to pigs in the CON group, which was consistent with previous findings showing that reduced feeding frequency decreased growth rate but increased the feeding efficiency of pigs [

1,

22]. Previous studies showed that higher dietary energy concentration could increase ADG and decrease ADFI in pigs [

8]. Our study found that increasing dietary NE density improved the ADG and feed efficiency of pigs without affecting ADFI. Additionally, in the current study, restricted-fed pigs exhibited the highest feeding efficiency when the energy density was set at 2370 kcal NE kg

−1, indicating that the increase in energy density was not simply linearly compensating for the insufficient intake-induced impairment in F/G [

23].

Previous findings have demonstrated that modulating feeding frequency could alter the partitioning of energy towards the deposition of lean and fat tissue [

4,

24]. The present study indicated that restricted feeding significantly reduced dressing percentage, backfat thickness, and loin muscle area, which was consistent with previous evidence suggesting that reduced feeding frequency could shape carcass composition by reducing fat deposition [

5,

24]. An increase in dietary energy density led to improvements in carcass parameters, indicating that higher energy supply could partially counteract the negative impacts of feeding restriction on carcass traits [

25,

26]. Color is the most important attribute of meat quality perceived by consumers. In this study, reduced feeding frequency significantly decreased the L* of LDM, which was consistent with previous findings that lower L* in muscle of pigs with longer feeding intervals [

27]. It was reported that an increase in dietary energy contributed to an elevation in the b* of chicken meat and pork [

28]. Likewise, in the current study, higher dietary energy increased the b* of muscle in restricted-fed pigs. Therefore, controlling the energy density of diets in the range of 2370–2410 kcal NE kg

−1 under the restricted feeding regime can not only avoid the excessive fat deposition caused by higher energy intake, but also improve the color of the pork, aligning with consumer purchase preferences.

The content of dietary nutrients largely determined the nutritional value of pork [

29]. Consistent with previous findings, the results of our study showed that reducing the feeding frequency could decrease the intramuscular fat (IMF) content in pigs [

30]. However, IMF levels increased with the increase in energy density, indicating that elevating dietary energy density can restore restricted feeding regime-caused IMF reduction. Fatty acid composition analysis showed that the proportion of major fatty acids was unchanged, indicating the adjustment of energy density had a limited effect on muscle fatty acid profile, even under restricted feeding conditions. The results were consistent with a previous study [

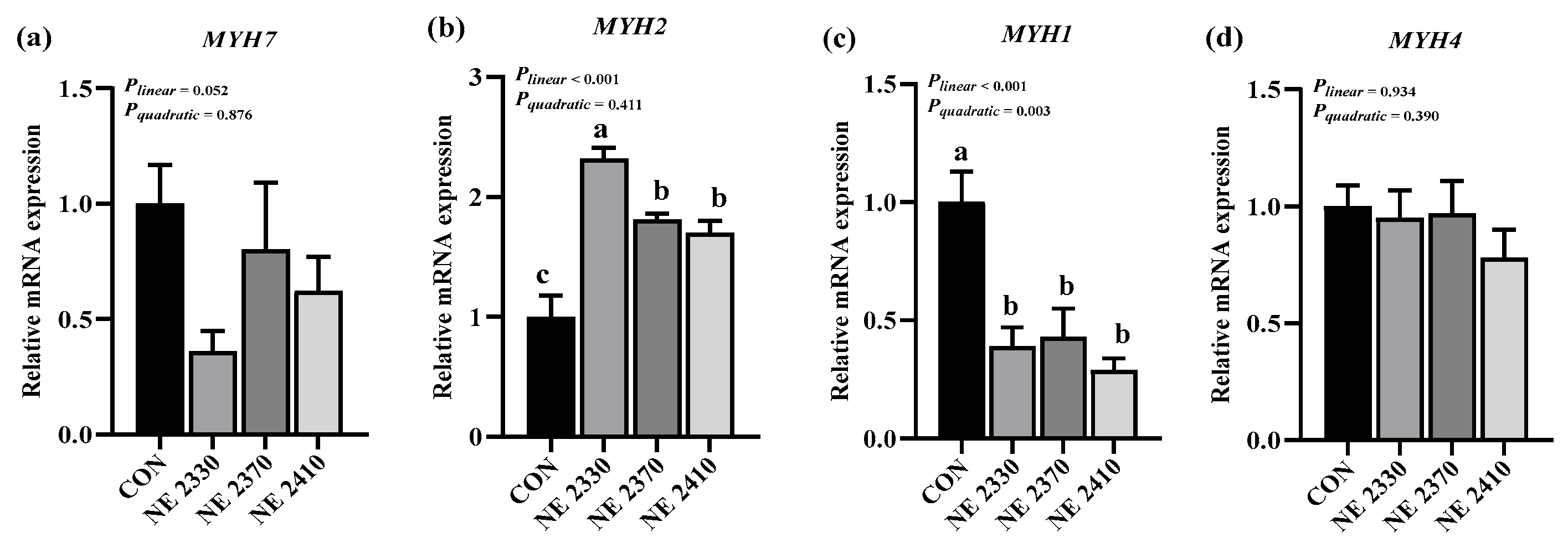

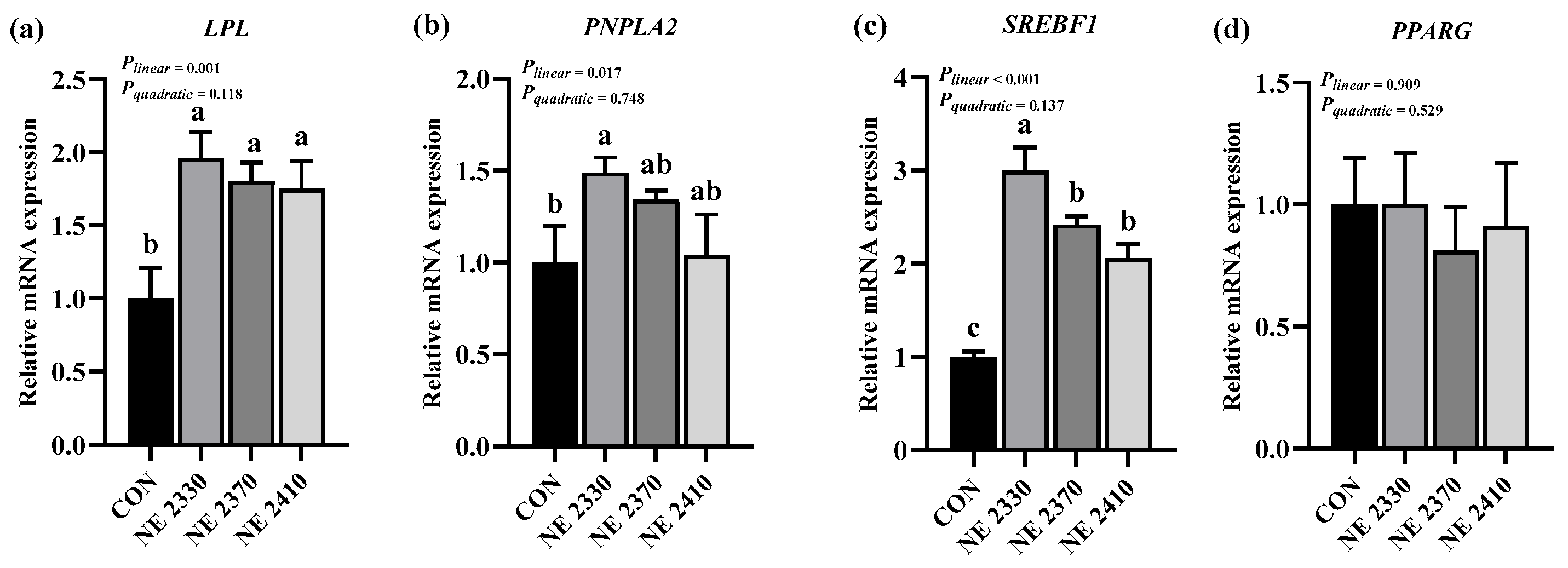

31], possibly because the increase in dietary energy density did not reach the threshold for significant changes in fatty acid composition. In the present study, treatment groups exhibited increased expression of lipid metabolism-related genes, including

CD36,

LPL,

PNPLA2,

CPT1B, and

SREBF1, which was consistent with the previous finding that increasing the frequency of feeding decreases the expression of fat metabolism genes [

32]. The increase in dietary energy density significantly down-regulated the expression of

CD36,

LPL,

PNPLA2,

CPT1B, and

SREBF1 in restricted-fed pigs, which was similar to previous evidence demonstrating that higher dietary energy density upregulated the expression of these lipogenic genes and facilitated lipid metabolism [

33].

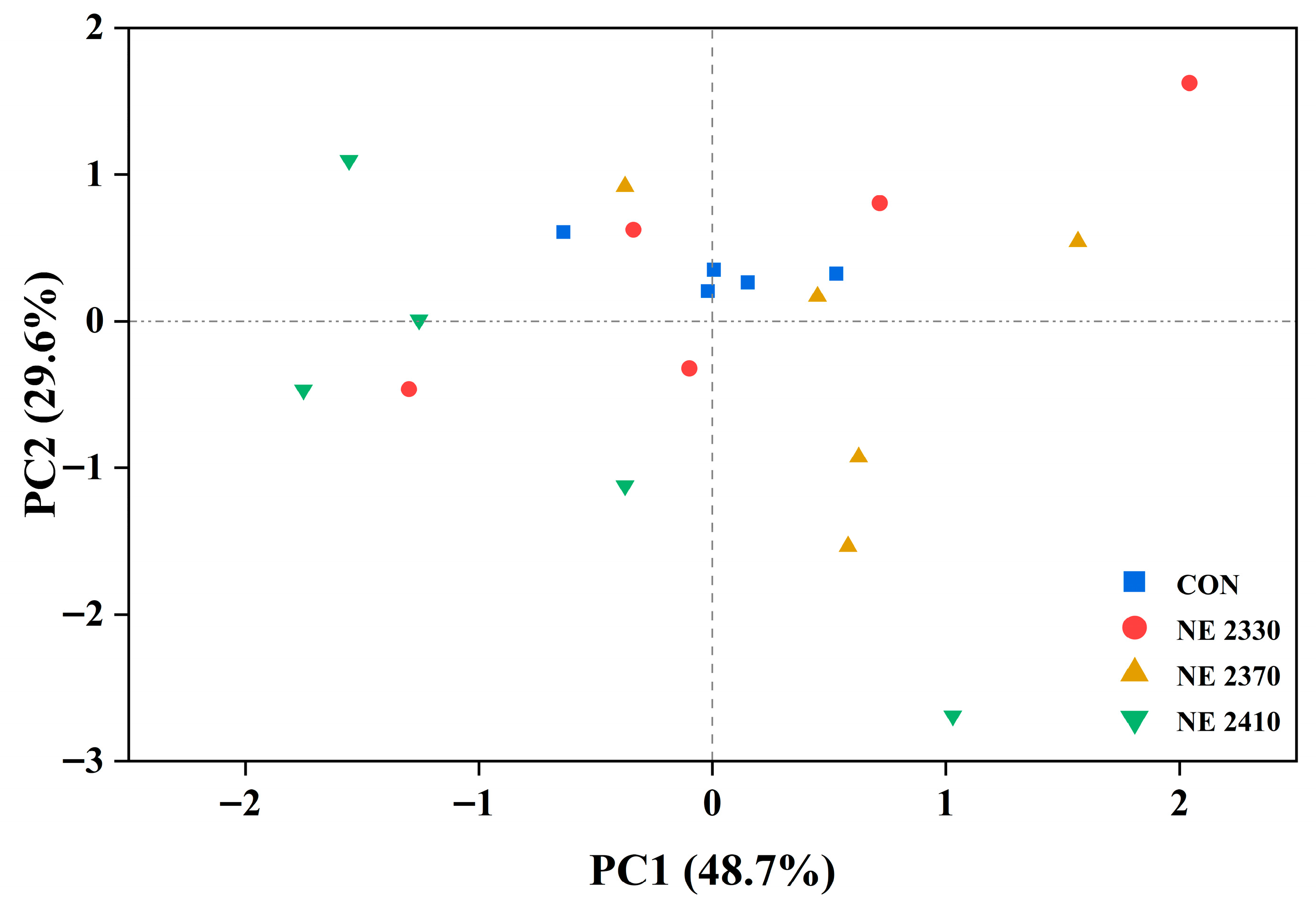

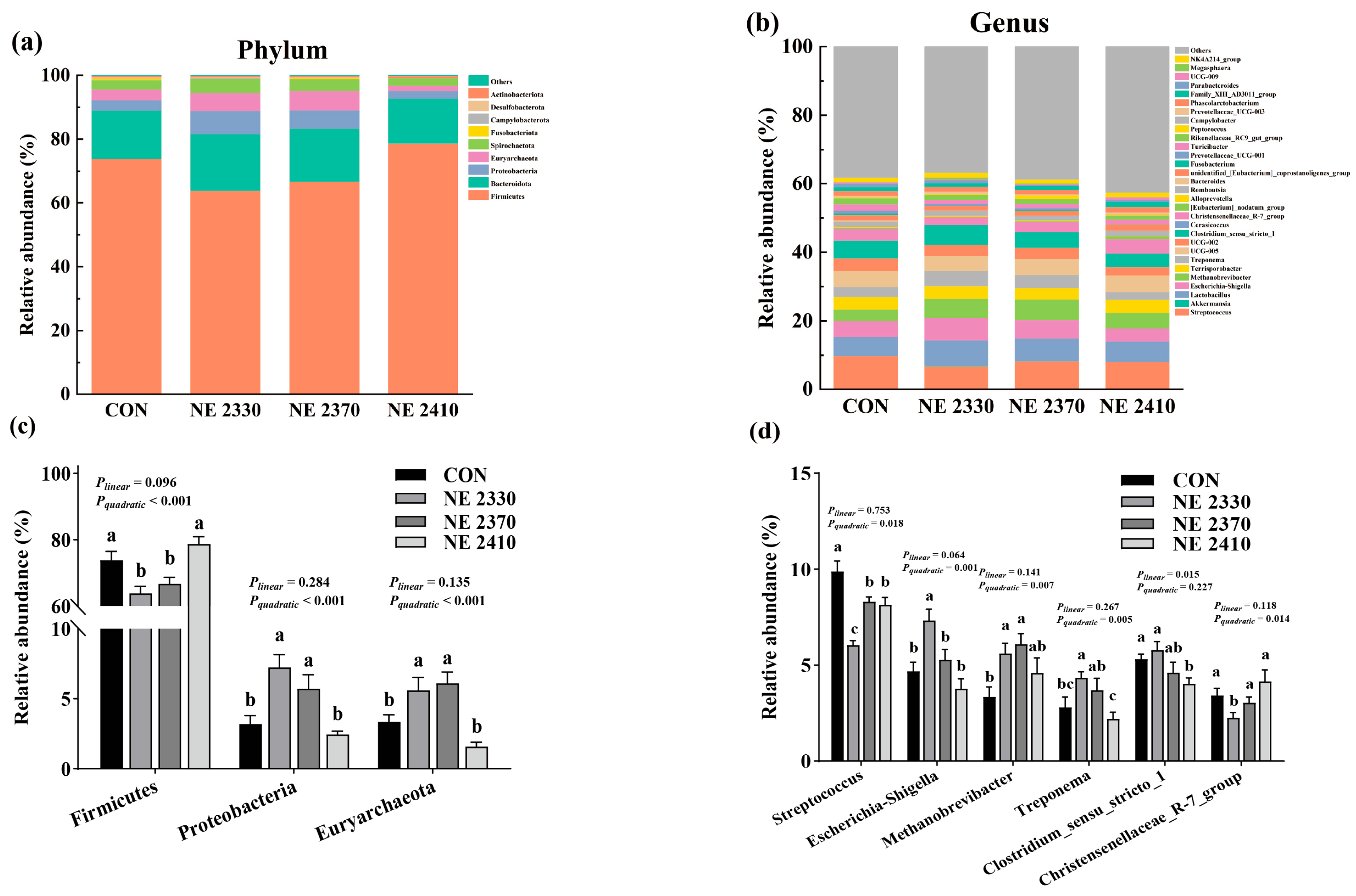

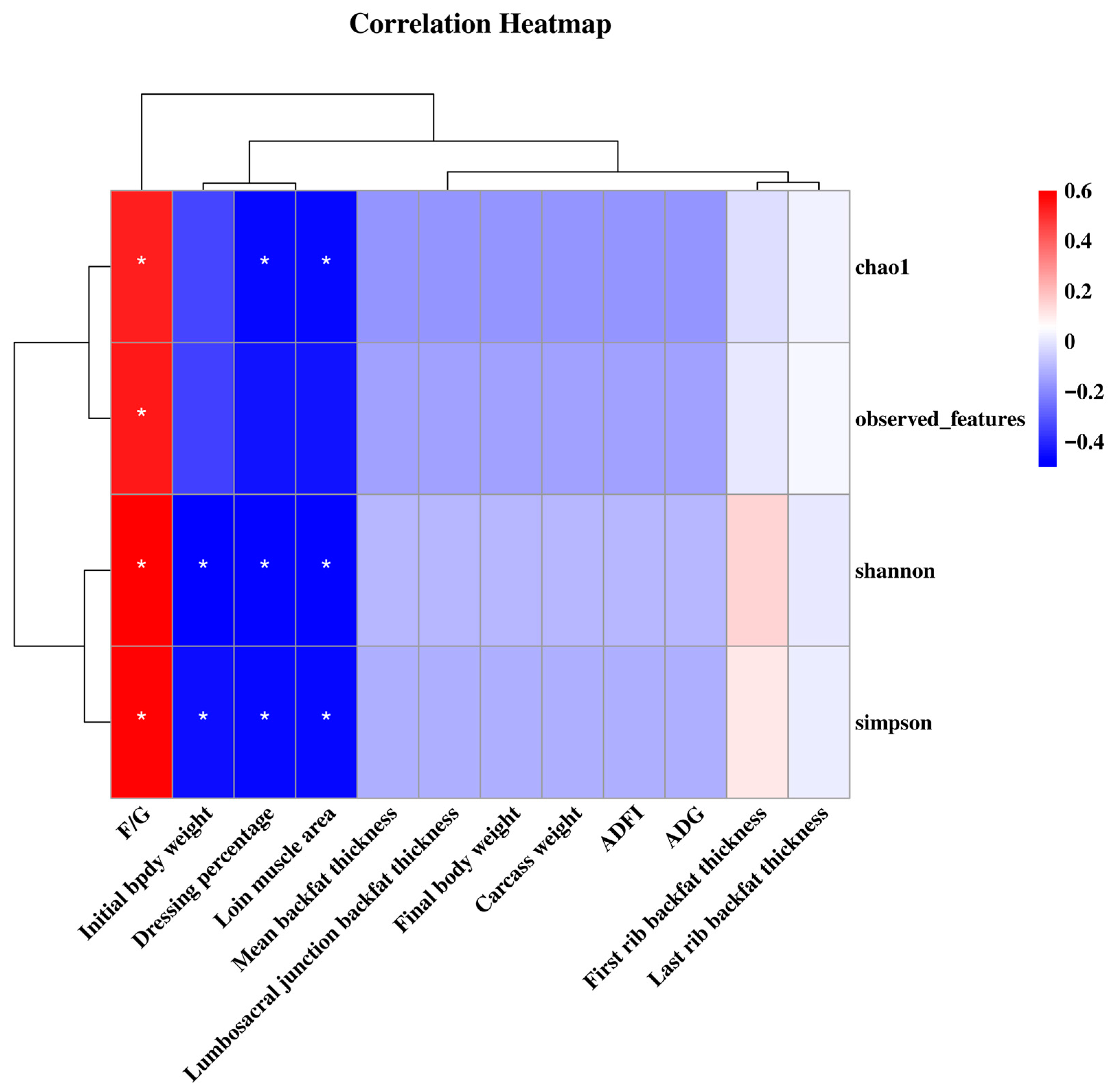

In this study, Chao1 and Shannon indices were significantly decreased in the NE 2410 group compared to the CON group, which was consistent with the previous findings that intestinal flora alpha diversity was reduced in mice fed a high-fat and high-sugar diet [

34]. The reduction in microbial diversity directly impairs nutrient metabolism efficiency. High diversity means that the microbiota can more comprehensively break down complex carbohydrates, lipids, and other nutrients in the feed. The excessively high energy concentration in the NE 2410 group may have inhibited the abundance of beneficial degradative bacteria, leading to a decreased ability of the microbiota to break down dietary fiber and synthesize SCFAs. The bacteria falling in phylum Firmicutes has been associated with enhanced fat deposition in animals [

35]. In this study, the abundance of Firmicutes in pigs of the NE 2330 group was decreased compared to the CON group. However, under restricted feeding conditions, the abundance of Firmicutes increased continuously with the elevation of dietary energy density, indicating that the increase in energy density led to an increase in backfat thickness in restricted-fed pigs by increasing the abundance of Firmicutes. Phyla Proteobacteria and Euryarchaeota have been associated with reduced fat deposition in hosts, as indicated by higher abundances of these two phyla in rodents with lower body fat percentage [

36,

37]. In this study, the abundances of Proteobacteria and Euryarchaeota in pigs of the NE 2330 group were increased compared to the CON group. Additionally, the abundances of Proteobacteria and Euryarchaeota in restricted-fed pigs were decreased as dietary energy density increased. Genus

Christensenellaceae_R-7_group has been recognized as a biomarker improving the backfat thickness of pigs [

38]. In this study, a restricted feeding regime significantly reduced the

Christensenellaceae_R-7_group abundance, while the elevation of dietary energy density increased the

Christensenellaceae_R-7_group abundance, indicating that the changes in backfat thickness of pigs in response to feeding regime and dietary energy density might be attributed to the altered proportion of this taxon. Consistent with previous findings, our study found that higher dietary energy increased the abundance of

Methanobrevibacter in restricted-fed pigs [

39]. Previous studies showed that the abundances of

Treponema were negatively associated with lipid deposition in pigs. Our study found that pigs in the NE 2410 group had a lower level of genus

Treponema in cecal content than pigs in the NE 2330 and NE 2370 groups, indicating that the increase in dietary energy density might lead to an increase in backfat thickness in restricted-fed pigs that was associated with decreased abundance of

Treponema.