Distinct Effects of GnRH Immunocastration Versus Surgical Castration on Gut Microbiota

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Experimental Animals and Design

2.3. Sample Collection

2.4. Microbial DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

2.5. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Data Processing and Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. GnRH Immunocastration Reduced Gonadal Weight in SD Rats

3.2. General Characteristics of Gut Microbiota in SD Rats

3.3. Surgical Castration Altered Gut Microbial Diversity and Composition in SD Rats

3.4. GnRH Immunocastration Modulates the Gut Microbiota in a Time and Sex-Dependent Manner

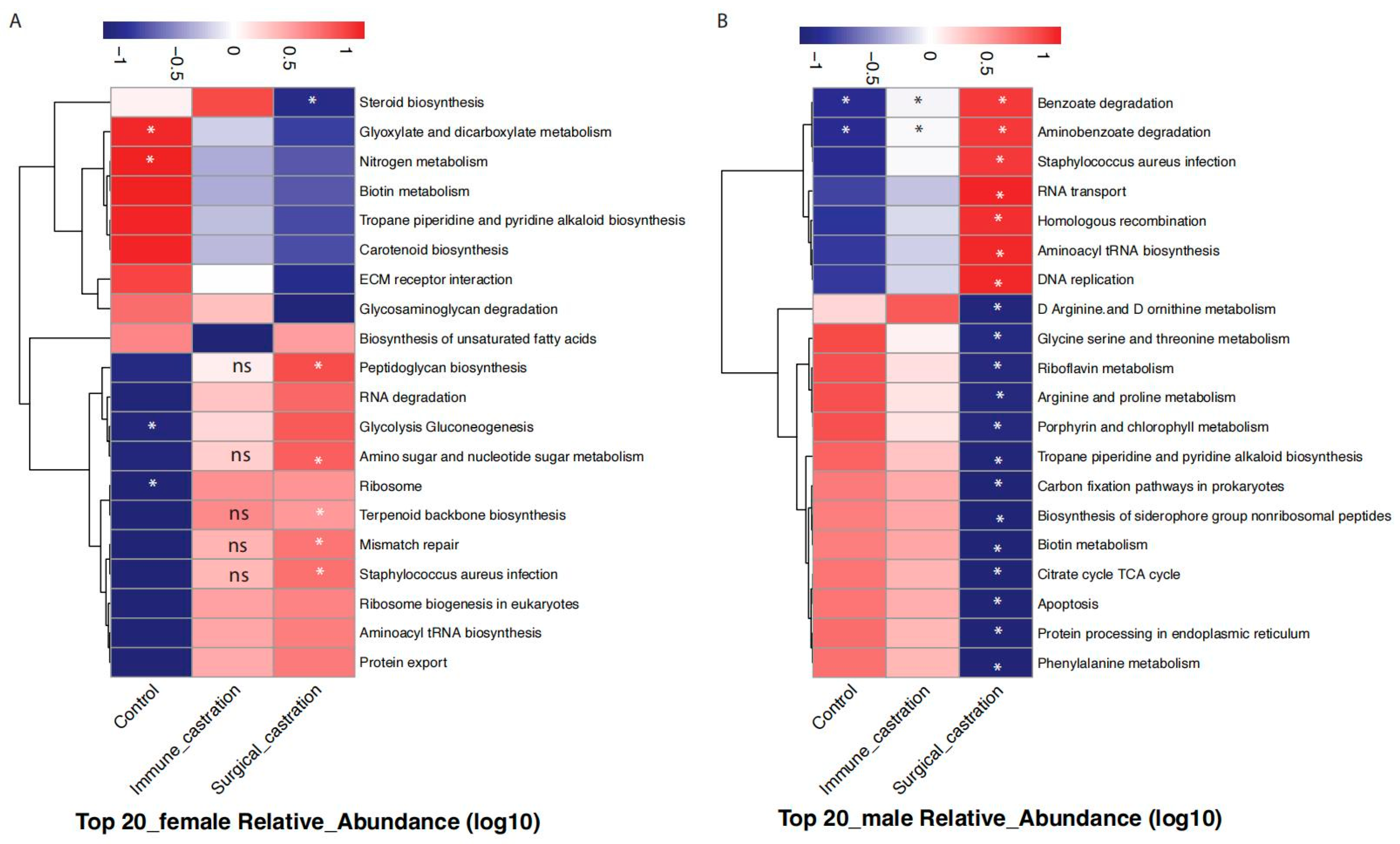

3.5. Comparative Analysis of Gut Microbiota Alterations Induced by GnRH Immunocastration and Surgical Castration in SD Rats

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moudgal, N.; Jeyakumar, M.; Krishnamurthy, H.N.; Sridhar, S.; Krihsnamurthy, H.; Martin, F. Development of male contraceptive vaccine—A perspective. Hum. Reprod. Update 1997, 3, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aluwé, M.; Tuyttens, F.A.; Millet, S. Field experience with surgical castration with anaesthesia, analgesia, immunocastration and production of entire male pigs: Performance, carcass traits and boar taint prevalence. Animal 2015, 9, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prunier, A.; Bonneau, M.; von Borell, E.; Cinotti, S.; Gunn, M.; Fredriksen, B.; Giersing, M.; Morton, D.; Tuyttens, F.; Velarde, A. A review of the welfare consequences of surgical castration in piglets and the evaluation of non-surgical methods. Anim. Welf. 2006, 15, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantas, D.; Papatsiros, V.; Tassis, P.; Tzika, E.; Pearce, M.C.; Wilson, S. Effects of early vaccination with a gonadotropin releasing factor analog-diphtheria toxoid conjugate on boar taint and growth performance of male pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 92, 2251–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunius, C.; Zamaratskaia, G.; Andersson, K.; Chen, G.; Norrby, M.; Madej, A.; Lundström, K. Early immunocastration of male pigs with Improvac((R))—Effect on boar taint, hormones and reproductive organs. Vaccine 2011, 29, 9514–9520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, D.L. Immunization against GnRH in male species (comparative aspects). Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2000, 60–61, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, J.K.; Friary, J.A.; Miller, L.A.; Tucker, S.J.; Fagerstone, K.A. Long-term fertility control in female cats with GonaCon, a GnRH immunocontraceptive. Theriogenology 2011, 76, 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.; Pedersen, H.G.; Sandøe, P. Beyond castration and culling: Should we use non-surgical, pharmacological methods to control the sexual behavior and reproduction of animals? J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2018, 31, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.F.; Li, J.; Cao, X.; Du, X.; Meng, F.; Zeng, X. Surgical castration but not immuncastration is associated with reduced hypothalamic GnIH and GHRH/GH/IGF-I axis function in male rats. Theriogenology 2016, 86, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.F.; Cao, X.-H.; Tang, J.; Du, X.-G.; Zeng, X.-Y. Active immunization against GnRH reduces the synthesis of GnRH in male rats. Theriogenology 2013, 80, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.F.; Li, J.L.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Ren, X.H.; Liu, G.C.; Cao, X.H.; Du, X.G.; Zeng, X.Y. Active immunization with GnRH-tandem-dimer peptide in young male rats reduces serum reproductive hormone concentrations, testicular development and spermatogenesis. Asian J. Androl. 2016, 18, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Han, X.F.; Ren, X.; Zeng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Song, T.; Cao, X.; Du, X.; Meng, F.; Tan, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Physiological interactions between the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and spleen in rams actively immunized against GnRH. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2016, 38, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massei, G.; Cowan, D.P.; Coats, J.; Bellamy, F.; Quy, R.; Pietravalle, S.; Brash, M.; Miller, L.A. Long-term effects of immunocontraception on wild boar fertility, physiology and behaviour. Wildl. Res. 2012, 39, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökdal, O.; Atay, O.; Ülker, H.; Kayaardı, S.; Kanter, M.; DeAvila, M.D.; Reeves, J.J. The effects of immunological castration against GnRH with recombinant OL protein (Ovalbumin-LHRH-7) on carcass and meat quality characteristics, histological appearance of testes and pituitary gland in Kivircik male lambs. Meat Sci. 2010, 86, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.Y.; Turkstra, J.; Jongbloed, A.; van Diepen, J.; Meloen, R.; Oonk, H.; Guo, D.; van de Wiel, D. Performance and hormone levels of immunocastrated, surgically castrated and intact male pigs fed ad libitum high- and low-energy diets. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2002, 77, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.M.; Chen, C.-C.; Lee, J.-W.; Hou, D.-L.; Huang, H.-H.; Ke, G.-M. Effects of a novel recombinant gonadotropin-releasing hormone-1 vaccine on the reproductive function of mixed-breed dogs (Canis familiaris) in Taiwan. Vaccine 2023, 41, 2214–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.Y.; Turkstra, J.A.; Meloen, R.H.; Liu, X.Y.; Chen, F.Q.; Schaaper, W.M.; Oonk, H.B.; Guo, D.Z.; van de Wiel, D.F. Active immunization against gonadotrophin-releasing hormone in Chinese male pigs: Effects of dose on antibody titer, hormone levels and sexual development. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2002, 70, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, W.C.; Hsieh, K.-L.; Chen, Y.-C.; Ho, C.H.; Hong, C.-S.; Chiang, C.-Y.; Wu, N.-C.; Chen, M.; Shih, J.-Y.; Chen, Z.-C.; et al. Comparison of surgical or medical castration-related cardiotoxicity in patients with prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2022, 207, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boleij, A.; Tjalsma, H. Gut bacteria in health and disease: A survey on the interface between intestinal microbiology and colorectal cancer. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2012, 87, 701–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Marcos, J.A.; Rangel-Zuñiga, O.A.; Jimenez-Lucena, R.; Quintana-Navarro, G.M.; Garcia-Carpintero, S.; Malagon, M.M.; Landa, B.B.; Tena-Sempere, M.; Perez-Martinez, P.; Lopez-Miranda, J.; et al. Influence of gender and menopausal status on gut microbiota. Maturitas 2018, 116, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markle, J.G.; Frank, D.N.; Mortin-Toth, S.; Robertson, C.E.; Feazel, L.M.; Rolle-Kampczyk, U.; von Bergen, M.; McCoy, K.D.; Macpherson, A.J.; Danska, J.S. Sex differences in the gut microbiome drive hormone-dependent regulation of autoimmunity. Science 2013, 339, 1084–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurkovetskiy, L.; Burrows, M.; Khan, A.A.; Graham, L.; Volchkov, P.; Becker, L.; Antonopoulos, D.; Umesaki, Y.; Chervonsky, A.V. Gender bias in autoimmunity is influenced by microbiota. Immunity 2013, 39, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oonk, H.B.; Turkstra, J.; Schaaper, W.; Erkens, J.; Weerd, M.S.-D.; van Nes, A.; Verheijden, J.; Meloen, R. New GnRH-like peptide construct to optimize efficient immunocastration of male pigs by immunoneutralization of GnRH. Vaccine 1998, 16, 1074–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rognes, T.; Flouri, T.; Nichols, B.; Quince, C.; Mahé, F. VSEARCH: A versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, G.M.; Maffei, V.J.; Zaneveld, J.R.; Yurgel, S.N.; Brown, J.R.; Taylor, C.M.; Huttenhower, C.; Langille, M.G.I. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.Z.; Gao, J.; Wu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Fu, H.; Ke, S.; Yang, H.; Chen, C.; Huang, L. Host gender and androgen levels regulate gut bacterial taxa in pigs leading to sex-biased serum metabolite profiles. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Li, D.; Ye, S.; Song, T.; Zeng, X. Multi-omics investigation of the mechanism underlying castration-induced subcutaneous fat deposition in male mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2025, 777, 152233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organski, A.C.; Rajwa, B.; Reddivari, A.; Jorgensen, J.S.; Cross, T.-W.L. Gut microbiome-driven regulation of sex hormone homeostasis: A potential neuroendocrine connection. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2476562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornman, K.S.; Loesche, W.J. Effects of estradiol and progesterone on Bacteroides melaninogenicus and Bacteroides gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 1982, 35, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.M.; Al-Nakkash, L.; Herbst-Kralovetz, M.M. Estrogen-gut microbiome axis: Physiological and clinical implications. Maturitas 2017, 103, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.L.; Madak-Erdogan, Z. Estrogen and microbiota crosstalk: Should we pay attention? Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 27, 752–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, N.; Hanaoka, R.; Hanada, K.; Izawa, T.; Inui, H.; Yamaji, R. Hypogonadism alters cecal and fecal microbiota in male mice. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.; Hwang, Y.-J.; Shin, M.-J.; Yi, H. Difference in the gut microbiome between ovariectomy-induced obesity and diet-induced obesity. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 27, 2228–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Du, H.; Tian, W.; Xie, H.; Zhang, B.; Fu, W.; Li, Y.; Ling, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, F.; et al. Effect of GnRH immunocastration on immune function in male rats. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1023104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, F.; Wendling, D.; Demougeot, C.; Prati, C.; Verhoeven, F. Cytokines and intestinal epithelial permeability: A systematic review. Autoimmun. Rev. 2023, 22, 103331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giambra, V.; Pagliari, D.; Rio, P.; Totti, B.; Di Nunzio, C.; Bosi, A.; Giaroni, C.; Gasbarrini, A.; Gambassi, G.; Cianci, R. Gut microbiota, inflammatory bowel disease, and cancer: The role of guardians of innate immunity. Cells 2023, 12, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.M.; Chen, C.-C.; Hou, D.-L.; Ke, G.-M.; Lee, J.-W. Effects of a recombinant gonadotropin-releasing hormone vaccine on reproductive function in adult male ICR mice. Vaccines 2021, 9, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Bujanda, Z.A.; Haffner, M.C.; Chaimowitz, M.G.; Chowdhury, N.; Venturini, N.J.; Patel, R.A.; Obradovic, A.; Hansen, C.S.; Jacków, J.; Maynard, J.P.; et al. Castration-mediated IL-8 promotes myeloid infiltration and prostate cancer progression. Nat. Cancer 2021, 2, 803–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rico, J.L.; Reardon, K.F.; De Long, S.K. Inoculum microbiome composition impacts fatty acid product profile from cellulosic feedstock. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 323, 124532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotton, S.; Clayton, C.A.; Tropini, C. Microbial endocrinology: The mechanisms by which the microbiota influences host sex steroids. Trends Microbiol. 2023, 31, 1131–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, R.; Wang, M.; Peng, R.; Fu, S.; Fu, A.; Le, J.; Yao, Q.; Yuan, T.; Chi, H.; et al. 3β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase expressed by gut microbes degrades testosterone and is linked to depression in males. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 329–339.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kong, F.; Yang, R.; Zhou, X.; Shen, Y.; Wei, W.; Zeng, X.; Du, X.; Han, X. Distinct Effects of GnRH Immunocastration Versus Surgical Castration on Gut Microbiota. Animals 2025, 15, 3512. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243512

Kong F, Yang R, Zhou X, Shen Y, Wei W, Zeng X, Du X, Han X. Distinct Effects of GnRH Immunocastration Versus Surgical Castration on Gut Microbiota. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3512. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243512

Chicago/Turabian StyleKong, Fanli, Ruohan Yang, Xingyu Zhou, Yuanyuan Shen, Wenhao Wei, Xianyin Zeng, Xiaogang Du, and Xinfa Han. 2025. "Distinct Effects of GnRH Immunocastration Versus Surgical Castration on Gut Microbiota" Animals 15, no. 24: 3512. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243512

APA StyleKong, F., Yang, R., Zhou, X., Shen, Y., Wei, W., Zeng, X., Du, X., & Han, X. (2025). Distinct Effects of GnRH Immunocastration Versus Surgical Castration on Gut Microbiota. Animals, 15(24), 3512. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243512