Study of the Skull and Brain in a Cape Genet (Genetta tigrina) Using Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Simple Summary

Abstract

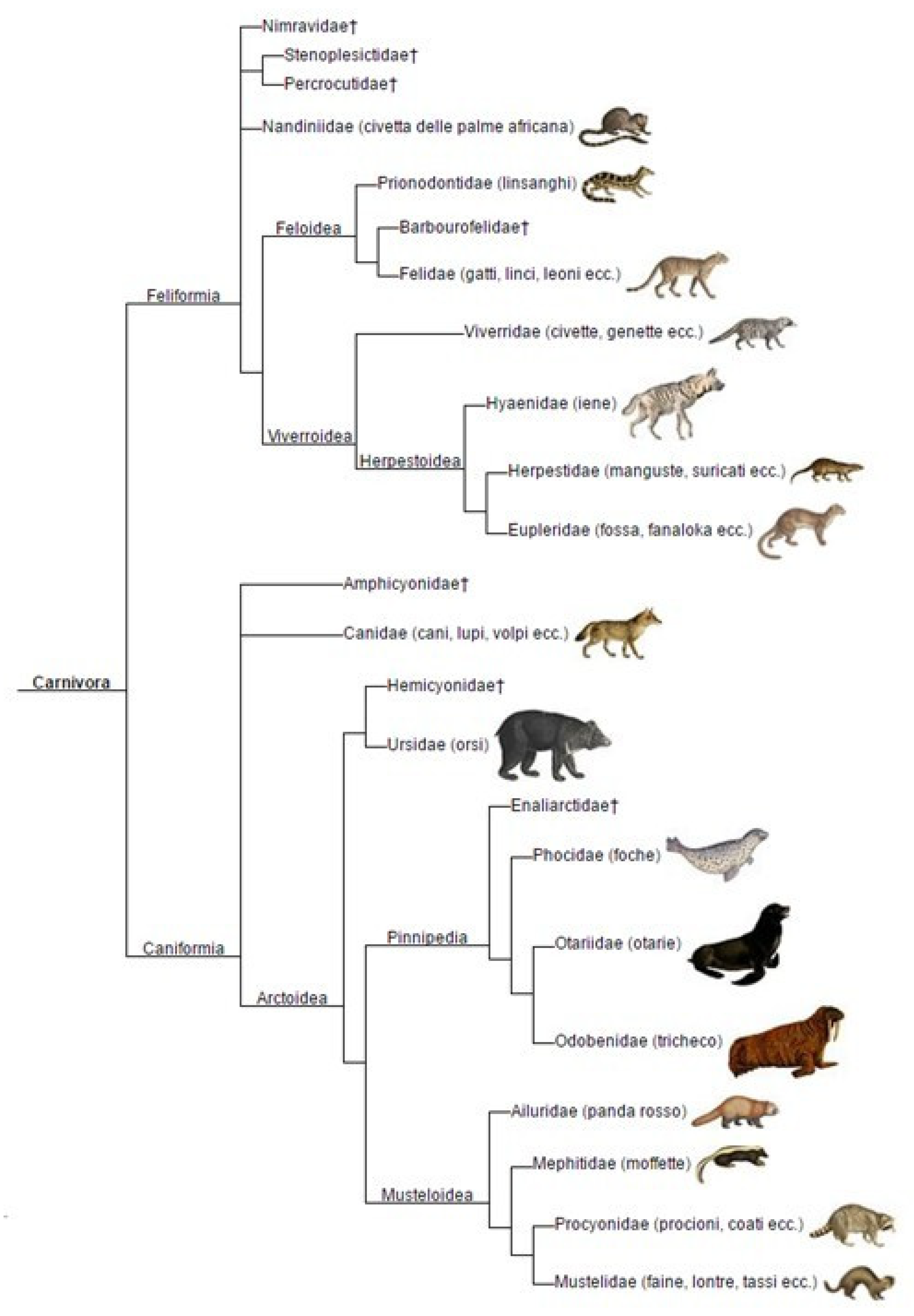

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subject Description

2.2. Anesthesia

2.3. Computed Tomography (CT)

2.4. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

3. Results

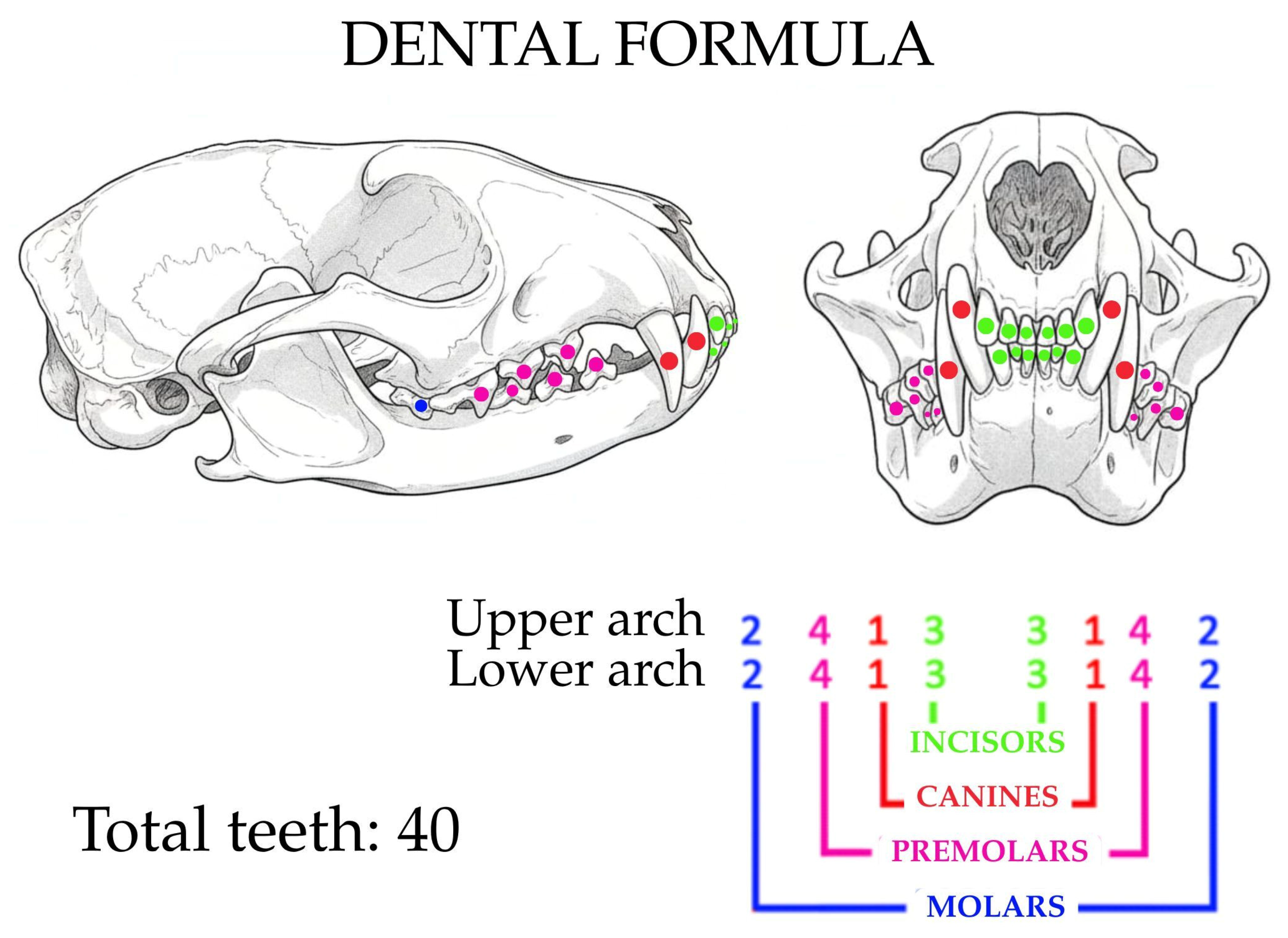

3.1. Oral Cavity

3.2. Computed Tomography (CT)

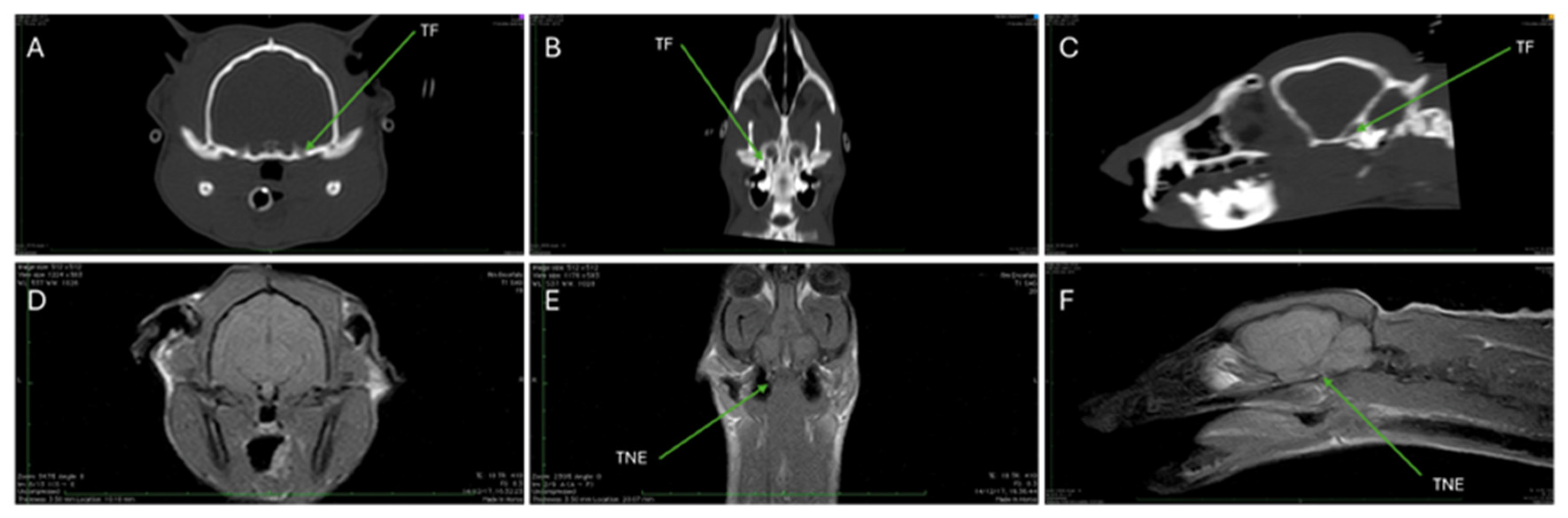

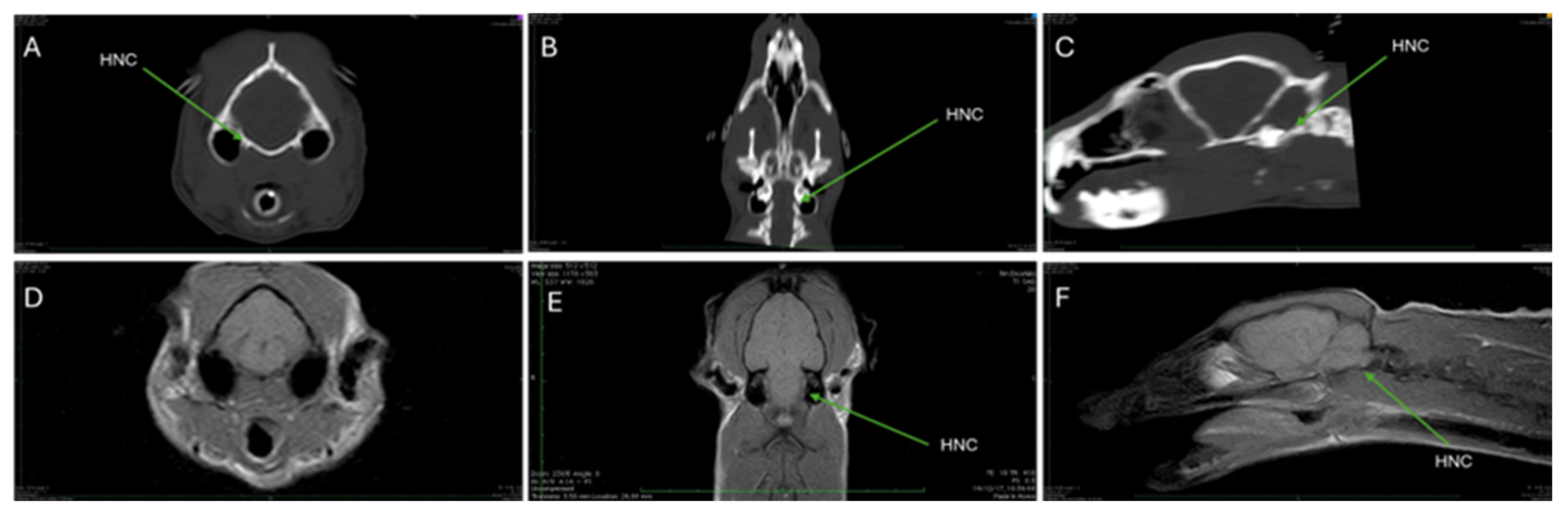

3.3. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | Computed tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| T1W | T1-weighted |

| T2W | T2-weighted |

| T2F | T2 FLAIR |

| TRS | Transverse |

| SAG | Sagittal |

| DOR | Dorsal |

| RT/TR | Repeat time |

| ET/TE | Echo time |

| ST | Thickness |

| MPR | Multiplanar reconstruction |

| DICOM | Digital imaging and communications in medicine |

| WL | Window level |

| WW | Widht |

| FoV | Field of view |

| TF | Trigeminal foramen |

| TNE | Trigeminal nerve emergency |

| HNC | Hypoglossal nerve canal |

| MF | Mental foramina |

| ROIC | Rostral opening of the infraorbital canal |

| CV | Cerebellar vermis |

| FV | Fourth ventricle |

| HN | Hypoglossal nerve |

| RPC | Rostral portion of the cerebellum |

| OLT | Occipital lobe of the telencephalon |

| LV | Lateral ventricles |

| TV | Third ventricle |

| T | Thalamus |

| CC | Corpus callosum |

| IC | Internal capsule |

| CN | Caudate nucleus |

| SS | Sphenoid sinus |

| OB | Olfactory bulb |

| ON | Optic nerve |

| TC | Tentorium cerebelli |

| FM | Foramen magnum |

| OC | Optic chiasm |

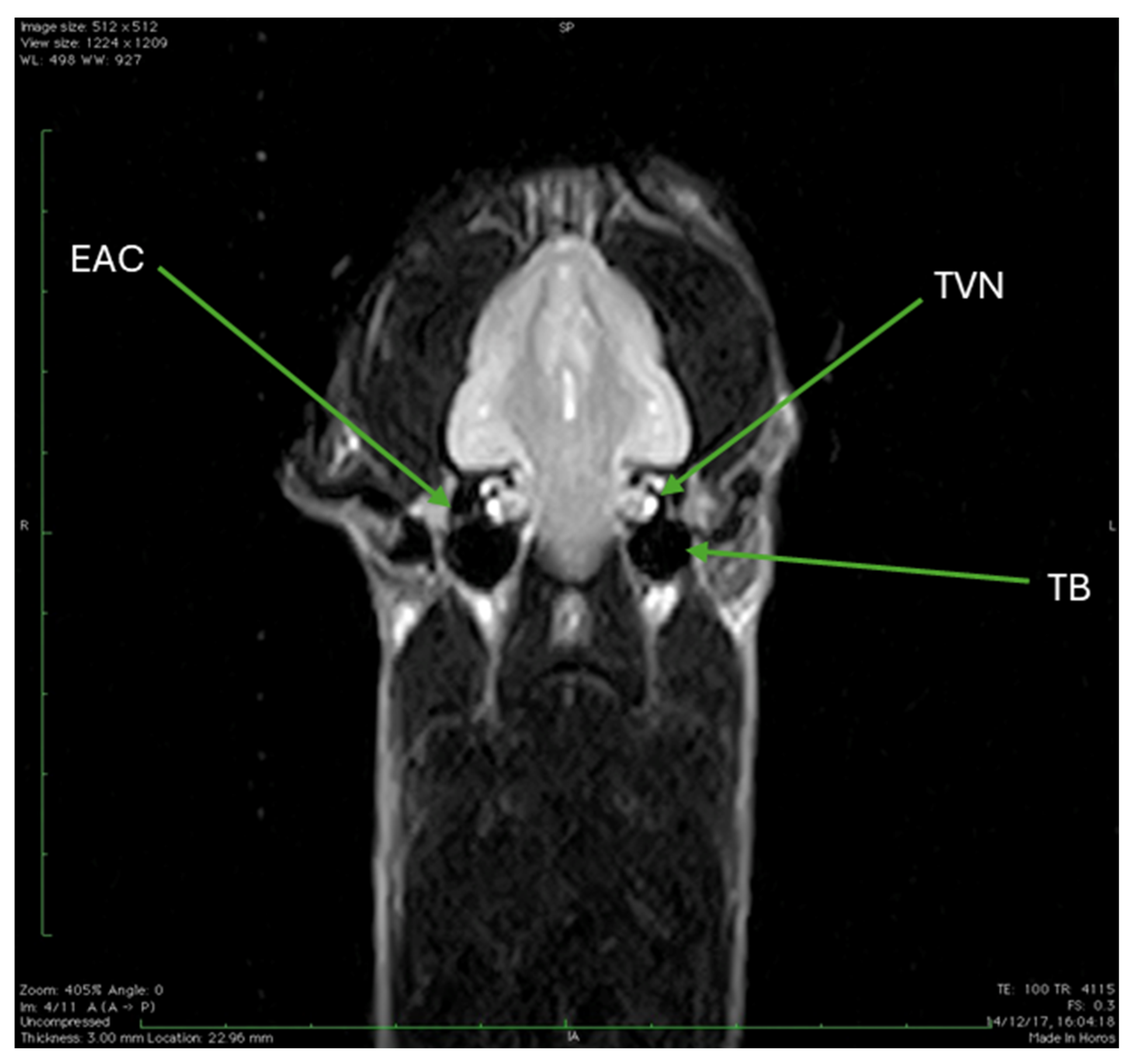

| EAC | External auditory canal |

| TVN | Trochlear vestibular nerve |

| TB | Tympanic bulla |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

Appendix A

References

- Gaubert, P. Integrative taxonomy and phylogenetic systematics of the Genets (Carnivora, Viverridae, Genetta): A new classification of the most speciose carnivoran genus in Africa. In African Biodiversity: Molecules, Organisms, Ecosystems; Huber, B.A., Sinclair, B.J., Lampe, K.-H., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M.E. The functional anatomy of the forelimb of some african viverridae (Carnivora). J. Morphol. 1974, 143, 307–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.E. The functional anatomy of the hindlimb of some african viverridae (Carnivora). J. Morphol. 1976, 148, 227–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, W.K.; Hellman, M. On the evolution and major classification of the civets (Viverridae) and allied fossil and recent carnivora: A phylogenetic study of the skull and dentition. Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 1939, 81, 309–392. [Google Scholar]

- Popowics, T.E. Postcanine dental form in the Mustelidae and Viverridae (Carnivora: Mammalia). J. Morphol. 2003, 256, 322–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, P.C.; Debroy, S.; Choudhary, O.P.; Kalita, A.; Doley, P.J. Morphological and morphometrical Studies on the skull of binturong (Arctictis binturong). J. Anim. Res. 2020, 10, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, M.; Hunt, J.R. Basicranial anatomy of the living linsangs Prionodon and Poiana (Mammalia, Carnivora, Viverridae), with comments on the early evolution of aeluroid carnivorans. Am. Mus. Novit. 2001, 2001, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Spadola, F.; Barillaro, G.; Morici, M.; Nocera, A.; Knotek, Z. The practical use of computed tomography in evaluation of shell lesions in six loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta). Vet. Med. 2016, 61, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauridsen, H.; Hansen, K.; Wang, T.; Agger, P.; Andersen, J.L.; Knudsen, P.S.; Rasmussen, A.S.; Uhrenholt, L.; Pedersen, M. Inside out: Modern imaging techniques to reveal animal anatomy. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, N.; Nourinezhad, J.; Moarabi, A.; Janeczek, M. Sectional anatomy with micro-computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging correlation of the middle and caudal abdominal regions in the Syrian Hamster (Mesocricetus auratus). Animals 2025, 15, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuccelli, T.; Crosta, L.; Costa, G.L.; Schnitzer, P.; Sawmy, S.; Spadola, F. Predisposing anatomical factors of humeral fractures in birds of prey: A preliminary tomographic comparative study. J. Avian Med. Surg. 2021, 35, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraft, S.L.; Gavin, P.R.; Wendling, L.R.; Reddy, V.K. Canine brain anatomy on magnetic resonance images. Vet. Radiol. 1989, 30, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; Covelli, E.M.; Meomartino, L.; Lamb, C.R.; Brunetti, V.A. Computed tomographic anatomy of the canine inner and middle ear. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2005, 43, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couturier, L.; Degueurce, C.; Ruel, Y.; Dennis, R.; Begon, D. Anatomical study of cranial nerve emergence and skull foramina in the dog using magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2005, 46, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, L.C.; Cauzinille, L.; Kornegay, J.N.; Tompkins, M.B. Magnetic resonance imaging of the normal feline brain. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 1995, 36, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, E.; Degueurce, C.; Ruel, Y.; Dennis, R.; Begon, D. Anatomic study of cranial nerve emergence and associated skull foramina in cats using CT and MRI. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2009, 50, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, H.; Obara, I.; Yoshida, T.; Kurohmaru, M.; Hayashi, Y.; Suzuki, N. Osteometrical and CT examination of the Japanese Wolf skull. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1997, 59, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czeibert, K.; Nagy, G.; Csörgő, T.; Donkó, T.; Petneházy, Ö.; Csóka, Á.; Garamszegi, L.Z.; Kolm, N.; Kubinyi, E. High-resolution computed tomographic (HRCT) image series from 413 canid and 18 felid skulls. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arencibia, A.; Vazquez, J.M.; Ramirez, J.A.; Ramirez, G.; Vilar, J.M.; Rivero, M.A.; Alayon, S.; Gil, F. Magnetic resonance imaging of the normal equine brain. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2001, 42, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, R.; Malalana, F.; McConnell, J.F.; Maddox, T. Anatomical study of cranial nerve emergence and skull foramina in the horse using magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2015, 56, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Caelenberg, A.I.; De Rycke, L.M.; Hermans, K.; Verhaert, L.; van Bree, H.J.; Gielen, I.M. Low-field magnetic resonance imaging and cross-sectional anatomy of the rabbit head. Vet. J. 2011, 188, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.; Kovacevíc, N.; Ho, S.; Henkelman, R.; Henderson, J. Development of a high resolution three-dimensional surgical atlas of the murine head for strains 129S1/SvImJ and C57Bl/6J using magnetic resonance imaging and micro-computed tomography. Neuroscience 2007, 144, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorr, A.; Lerch, J.; Spring, S.; Kabani, N.; Henkelman, R. High resolution three-dimensional brain atlas using an average magnetic resonance image of 40 adult C57Bl/6J mice. NeuroImage 2008, 42, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baygeldi, S.B.; Güzel, B.C.; Kanmaz, Y.A.; Yilmaz, S. Evaluation of skull and mandible morphometric measurements and three-dimensional modelling of computed tomographic images of porcupine (Hystrix cristata). Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2022, 51, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Bordon, D.; Encinoso, M.; Arencibia, A.; Jaber, J.R. Cranial investigations of Crested Porcupine (Hystrix cristata) by anatomical cross-sections and magnetic resonance imaging. Animals 2023, 13, 2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, J.R.; Morales-Bordon, D.; Morales, M.; Paz-Oliva, P.; Encinoso, M.; Morales, I.; Roldan-Medina, N.; Zarzosa, G.R.; Morales-Espino, A.; Ros, A.; et al. Comparative analysis of sectional anatomy, computed tomography and magnetic resonance of the cadaveric six-banded armadillo (Euphractus sexcintus) head. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loshuertos, Á.G.d.L.R.Y.; Espinosa, A.A.; Laguía, M.S.; Gil Cano, F.; Gomariz, F.M.; Fernández, A.L.; Zarzosa, G.R. A study of the head during prenatal and perinatal development of two fetuses and one newborn Striped Dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba, Meyen 1833) using dissections, sectional anatomy, CT, and MRI: Anatomical and functional implications in cetaceans and terrestrial mammals. Animals 2019, 9, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loshuertos, A.G.d.L.R.Y.; Laguía, M.S.; Espinosa, A.A.; Fernández, A.L.; Figueiredo, P.C.; Gomariz, F.M.; Collado, C.S.; Carrillo, N.G.; Zarzosa, G.R. Comparative anatomy of the nasal cavity in the common Dolphin Delphinus delphis L., Striped Dolphin Stenella coeruleoalba M. and Pilot Whale Globicephala melas T.: A developmental study. Animals 2021, 11, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumero-Hernández, M.; Encinoso, M.; Melian, A.; Nuez, H.A.; Salman, D.; Mohamad, J.R.J. Cross sectional anatomy and magnetic resonance imaging of the juvenile Atlantic Puffin head (Aves, Alcidae, Fratercula arctica). Animals 2023, 13, 3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stańczyk, E.K.; Gallego, M.L.V.; Nowak, M.; Hatt, J.; Kircher, P.R.; Carrera, I. 3.0 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging anatomy of the central nervous system, eye, and inner ear in birds of prey. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2018, 59, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E.G.; Quintana, M.E.; Bordon, D.M.; Garcés, J.G.; Nuez, H.A.; Jaber, J.R. Anatomical description of Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta cornuta) head by computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and gross-sections. Animals 2023, 13, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assheuer, J.; Sager, M. MRI and CT Atlas of the Dog; Iowa State University Press: Ames, IA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fourvel, J.-B. Civettictis braini nov. sp. (Mammalia: Carnivora), a new viverrid from the hominin-bearing site of Kromdraai (Gauteng, South Africa). Comptes Rendus Palevol 2018, 17, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaubert, P.; Veron, G. Exhaustive sample set among Viverridae reveals the sister-group of felids: The linsangs as a case of extreme morphological convergence within Feliformia. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2003, 270, 2523–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reidenberg, J.S.; Laitman, J.T. The new face of gross anatomy. Anat. Rec. 2002, 269, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnivora Phylogeny. Wikipedia. 2017. Available online: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Carnivora_phylogeny_%28ita%29.png (accessed on 1 May 2025).

| Sequences | Planes | RT (ms) | ET (ms) | ST (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2W | SAG | 5212 | 120 | 3.0 |

| T2W | TRS | 5860 | 100 | 3.5 |

| T2W | DOR | 4115 | 100 | 3.5 |

| T1W | SAG | 700 | 25 | 3.0 |

| T1W | TRS | 760 | 25 | 3.5 |

| T1W | DOR | 410 | 18 | 3.5 |

| FLAIR | TRA | 9518 | 90 | 3.5 |

| Skull Measurements | |

|---|---|

| Length | 54 mm |

| Max width | 31 mm |

| Skull thickness | 2 mm |

| Tympanic bullae | 9 mm × 4 mm |

| Tympanic bullae thickness | 1 mm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barillaro, G.; Marcianò, A.; Costa, S.; Marino, M.; Minniti, S.; Interlandi, C.D.; Spadola, F. Study of the Skull and Brain in a Cape Genet (Genetta tigrina) Using Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Animals 2025, 15, 3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233496

Barillaro G, Marcianò A, Costa S, Marino M, Minniti S, Interlandi CD, Spadola F. Study of the Skull and Brain in a Cape Genet (Genetta tigrina) Using Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233496

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarillaro, Giuseppe, Antonino Marcianò, Stella Costa, Matteo Marino, Simone Minniti, Claudia Dina Interlandi, and Filippo Spadola. 2025. "Study of the Skull and Brain in a Cape Genet (Genetta tigrina) Using Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging" Animals 15, no. 23: 3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233496

APA StyleBarillaro, G., Marcianò, A., Costa, S., Marino, M., Minniti, S., Interlandi, C. D., & Spadola, F. (2025). Study of the Skull and Brain in a Cape Genet (Genetta tigrina) Using Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Animals, 15(23), 3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233496