The Role of Dietary Schizochytrium Powder in Chicken Production Performance, Egg Quality, and Antioxidant Status

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Birds and Test Materials

2.3. Experimental Design and Management

2.4. Performance

2.5. Determination of Egg Quality and DHA Content in Eggs

2.6. Determination of Serum Biochemical and Antioxidant Indices

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Production Performance

3.2. Egg Quality and DHA Content

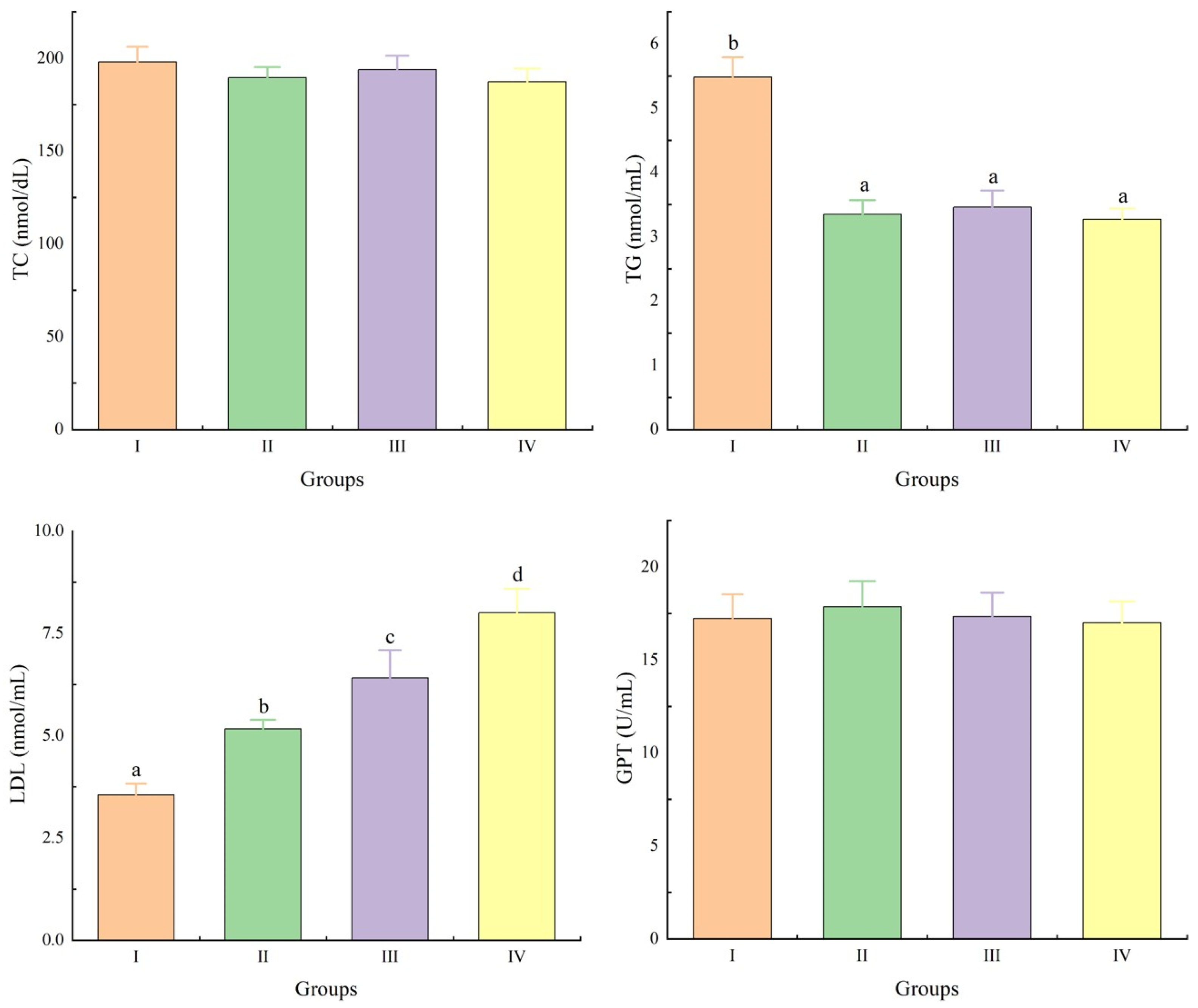

3.3. Serum Biochemical Parameters

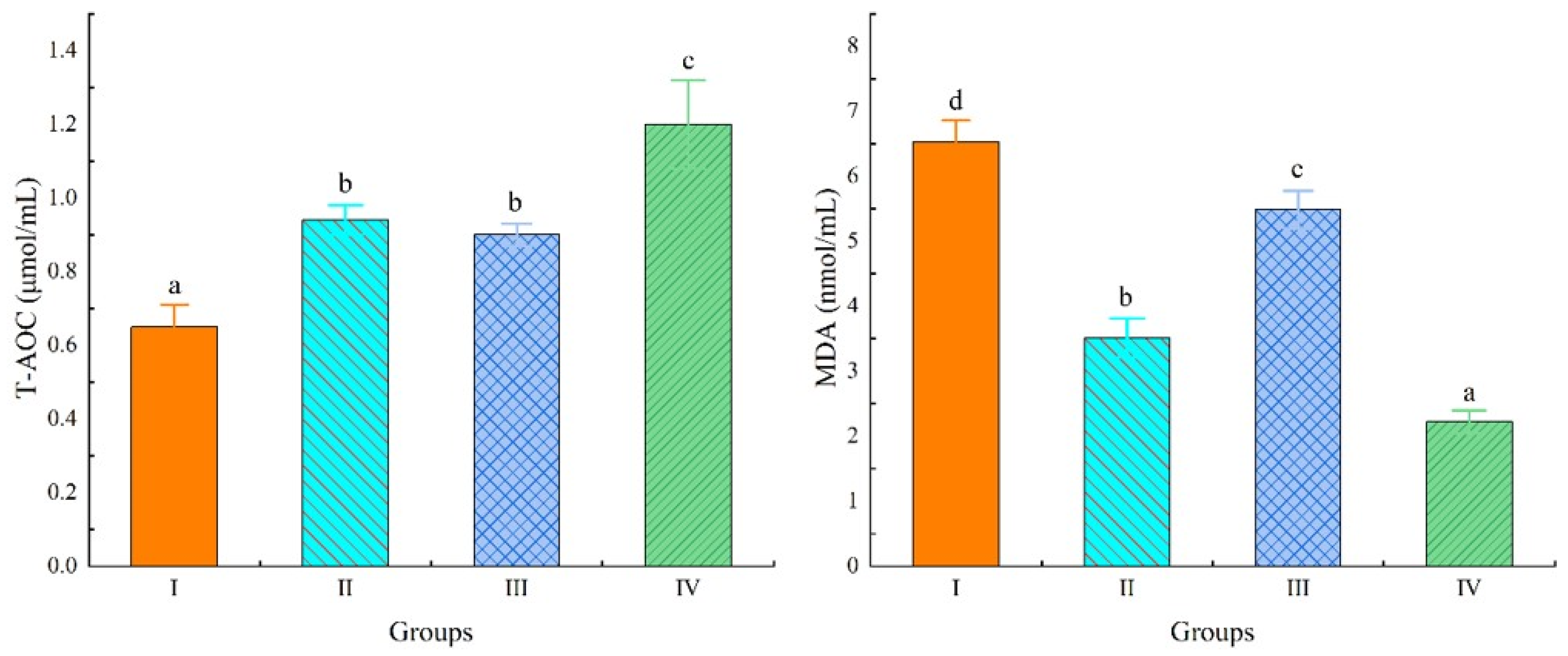

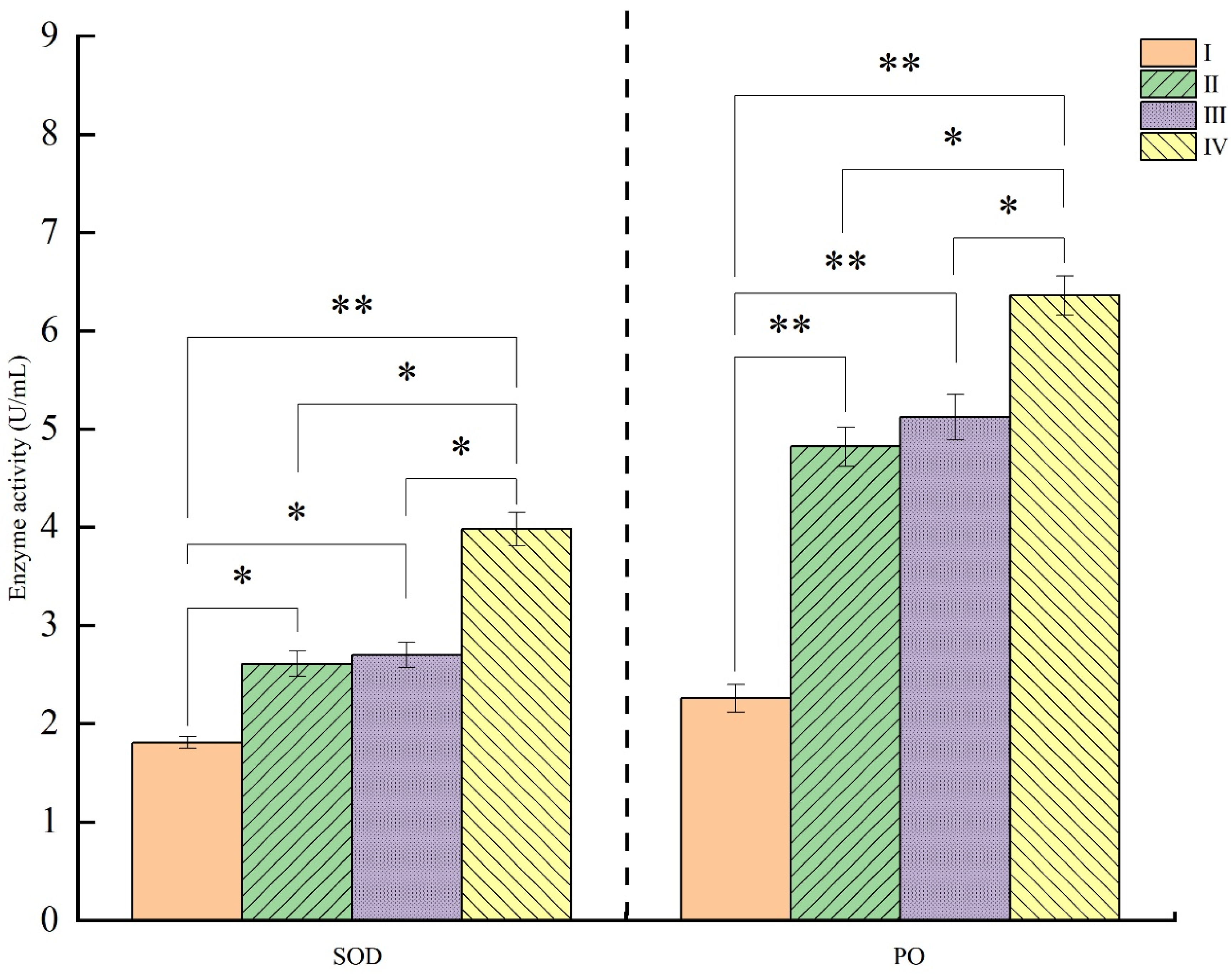

3.4. Antioxidant Indices

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yaguchi, T.; Tanaka, S.; Yokochi, T.; Nakahara, T.; Higashihara, T. Production of high yields of docosahexaenoic acid by Schizochytrium sp. strain SR21. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1997, 74, 1431–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, G.; Xu, Y.; Cao, X.; Li, Z.; Cao, M.; Chisti, Y.; He, N. Production of polyunsaturated fatty acids by Schizochytrium (Aurantiochytrium) spp. Biotechnol. Adv. 2022, 55, 107897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zang, X.; Zhang, X. Production of High Docosahexaenoic Acid by Schizochytrium sp. Using Low-cost Raw Materials from Food Industry. J. Oleo Sci. 2015, 64, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsuka, Y.; Okada, K.; Yamakawa, Y.; Ikuse, T.; Baba, Y.; Inage, E.; Fujii, T.; Izumi, H.; Oshida, K.; Nagata, S.; et al. ω-3 fatty acids attenuate mucosal inflammation in premature rat pups. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2011, 46, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuorinen, A.; Bailey-Hall, E.; Karagiannis, A.; Yu, S.; Roos, F.; Sylvester, E.; Wilson, J.; Dahms, I. Safety of Algal Oil Containing EPA and DHA in cats during gestation, lactation and growth. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 104, 1509–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smuts, C.M.; Borod, E.; Peeples, J.M.; Carlson, S.E. High-DHA eggs: Feasibility as a means to enhance circulating DHA in mother and infant. Lipids 2003, 38, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradbury, J. Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA): An Ancient Nutrient for the Modern Human Brain. Nutrients 2011, 3, 529–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, C.N.; Barrett, E.C.; Nelson, E.B.; Salem, N., Jr. The relationship of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) with learning and behavior in healthy children: A review. Nutrients 2013, 5, 2777–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenox, C.E.; Bauer, J.E. Potential adverse effects of omega-3 fatty acids in dogs and cats (Review). J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2013, 27, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komprda, T. Eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids as inflammation-modulating and lipid homeostasis influencing nutraceuticals: A review. J. Funct. Foods 2012, 4, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molendi-Coste, O.; Legry, V.; Leclercq, I.A. Why and How Meet n-3 PUFA Dietary Recommendations? Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2011, 2011, 364040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, F.; Valenzuela, R.; Catalina Hernandez-Rodas, M.; Valenzuela, A. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), a fundamental fatty acid for the brain: New dietary sources. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2017, 124, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, L.; Dietrich, T.; Marañón, I.; Villarán, M.C.; Barrio, R.J. Producing Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: A Review of Sustainable Sources and Future Trends for the EPA and DHA Market. Resources 2020, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargis, P.S.; Van Elswyk, M.E.; Hargis, B.M. Dietary Modification of Yolk Lipid with Menhaden Oil. Poult. Sci. 1991, 70, 874–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, X.; Wang, Q.; Li, X.; Xie, J.; Xie, S.; Peng, T.; Wang, C.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, H. Provision of Ultrasensitive Quantitative Gold Immunochromatography for Rapid Monitoring of Olaquindox in Animal Feed and Water Samples. Food Anal. Methods 2015, 9, 1919–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneel, C.; Lemahieu, C.; Fraeye, I.; Ryckebosch, E.; Muylaert, K.; Buyse, J.; Foubert, I. Impact of microalgal feed supplementation on omega-3 fatty acid enrichment of hen eggs. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.-C.; Ren, L.-J.; Chen, S.-L.; Zhang, L.; Ji, X.-J.; Huang, H. The roles of different salts and a novel osmotic pressure control strategy for improvement of DHA production by Schizochytrium sp. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 38, 2129–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, I.; Umbreen, H.; Nisa, M.u.; Al-Asmari, F.; Zongo, E. Supplementation of laying hens’ feed with Schizochytrium powder and its effect on physical and chemical properties of eggs. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, H.J.; Wang, X.C.; Wu, S.G.; Wang, J.; Xu, L.; Qi, G.H. Dietary choline and phospholipid supplementation enhanced docosahexaenoic acid enrichment in egg yolk of laying hens fed a 2% Schizochytrium powder-added diet. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 2786–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, N.; Riaz, S.; Mazhar, S.; Essa, R.; Maryam, M.; Saleem, Y.; Syed, Q.; Perveen, I.; Bukhari, B.; Ashfaq, S.; et al. Microbial production of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA): Biosynthetic pathways, physical parameter optimization, and health benefits. Arch. Microbiol. 2023, 205, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Zheng, N.; Zhao, S.; Liu, K.; Qu, X.; Yu, J.; Wang, J. DHA content in milk and biohydrogenation pathway in rumen: A review. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Zhan, T.; Teng, J.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Ma, L.; Bu, D. Different sources of DHA have distinct effects on the ruminal fatty acid profile and microbiota in vitro. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 21, 101875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Meza, D.A.; da Silva Sobrinho, A.G.; Almeida, M.T.C.; Borghi, T.H.; Granja-Salcedo, Y.T.; de Lima Valença, R.; de Andrade, N.; Cirne, L.G.A.; Ezequiel, J.M.B. Marine microalgae meal (Schizochytrium sp.) influence on intake, in vivo fermentation parameters and in vitro gas production and digestibility in sheep diets is dose-dependent. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2024, 318, 116130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, Z.; Chen, W.; Huang, F.; Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Yang, C. Algal oil alleviates antibiotic-induced intestinal inflammation by regulating gut microbiota and repairing intestinal barrier. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1081717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Su, H.; Guo, X.; Wu, J.; Li, Q.; Ni, G.; Jiang, R. Genetic parameters of the thick-to-thin albumen ratio and egg compositional traits in layer-type chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2019, 60, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisen, E.J.; Bohren, B.B.; McKean, H.E. The Haugh Unit as a Measure of Egg Albumen Quality. Poult. Sci. 1962, 41, 1461–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Jin, S.; Ma, C.; Wang, Z.; Fang, Q.; Jiang, R. Effect of strain and age on the thick-to-thin albumen ratio and egg composition traits in layer hens. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2019, 59, 416–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gu, H.; Zhu, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Song, W.; Tao, Z.; Xu, W.; Zhang, S.; Li, H. Optimization of Duck Semen Freezing Procedure and Regulation of Oxidative Stress. Animals 2025, 15, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curabay, B.; Sevim, B.; Cufadar, Y.; Ayasan, T. Effects of Adding Spirulina platensis to Laying Hen Rations on Performance, Egg Quality, and Some Blood Parameters. J. Hell. Vet. Med. Soc. 2024, 72, 2945–2952. [Google Scholar]

- Kaewsutas, M.; Sarikaphuti, A.; Nararatwanchai, T.; Sittiprapaporn, P.; Patchanee, P. The effects of dietary microalgae (Schizochytrium spp.) and fish oil in layers on docosahexaenoic acid omega-3 enrichment of the eggs. J. Appl. Anim. Nutr. 2016, 4, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Upadhaya, S.D.; Kim, I.H. Effect of Dietary Marine Microalgae (Schizochytrium) Powder on Egg Production, Blood Lipid Profiles, Egg Quality, and Fatty Acid Composition of Egg Yolk in Layers. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 28, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pangestuti, R.; Kim, S.-K. Biological activities and health benefit effects of natural pigments derived from marine algae. J. Funct. Foods 2011, 3, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsche, C.; Martínez de Toda, I.; Hernandez, O.; Jiménez, B.; Díaz, L.E.; Marcos, A.; De la Fuente, M. The supplementations with 2-hydroxyoleic acid and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids revert oxidative stress in various organs of diet-induced obese mice. Free Radic. Res. 2020, 54, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Groups | Treatment Plan |

|---|---|

| Group I | Control group with basal diet |

| Group II | Basal diet with 0.5% Schizochytrium powder |

| Group III | Basal diet with 1.0% Schizochytrium powder |

| Group IV | Basal diet with 2.0% Schizochytrium powder |

| Ingredients | Content | Nutrient Levels 2 | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corn, % | 64.75 | Metabolic energy, (MJ/kg) | 11.09 |

| Soybean meal, % | 24.30 | Dry matter, % | 87.60 |

| DL-methionine, % | 0.08 | Crude protein, % | 15.50 |

| L-lysine·HCl, % | 0.07 | Calcium, % | 3.50 |

| Limestone, % | 9.10 | Available phosphorus, % | 0.30 |

| CaHPO4, % | 1.00 | Methionine, % | 0.33 |

| NaCl, % | 0.38 | Sulfur amino acids, % | 0.59 |

| Premix 1, % | 0.22 | Lysine, % | 0.80 |

| Choline chloride, % | 0.10 | ||

| Total, % | 100.00 |

| Items | Groups | SEM | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | ANOVA | Linear | Quadratic | ||

| ADFI, g | 119.93 b | 118.11 b | 117.73 b | 109.52 a | 0.284 | 0.035 | 0.018 | 0.064 |

| AEW, g | 42.61 | 41.97 | 42.43 | 41.17 | 0.061 | 0.105 | 0.452 | 0.677 |

| FCR | 2.81 | 2.81 | 2.77 | 2.66 | 0.015 | 0.073 | 0.325 | 0.273 |

| LR, % | 80.56 b | 80.35 b | 79.05 b | 77.91 a | 0.649 | 0.031 | 0.020 | 0.014 |

| Items | Groups | SEM | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | ANOVA | Linear | Quadratic | ||

| ES, kg/cm2 | 40.13 a | 42.76 b | 42.44 b | 42.66 b | 0.076 | 0.032 | 0.101 | 0.021 |

| ET, mm | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.001 | 0.256 | 0.321 | 0.422 |

| EP, % | 10.31 | 10.71 | 10.67 | 10.77 | 0.023 | 0.682 | 0.261 | 0.312 |

| YP, % | 32.42 | 32.61 | 32.40 | 32.43 | 0.079 | 0.754 | 0.566 | 0.453 |

| AH, mm | 5.76 | 5.80 | 5.86 | 5.87 | 0.009 | 0.562 | 0.498 | 0.397 |

| HU | 82.60 | 82.50 | 82.67 | 82.57 | 0.077 | 0.236 | 0.413 | 0.564 |

| DHA, mg/kg | 0.90 a | 2.31 b | 2.58 b | 3.61 c | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.122 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Q.; Huang, H.; Li, C.; Huang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Kong, L.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Z. The Role of Dietary Schizochytrium Powder in Chicken Production Performance, Egg Quality, and Antioxidant Status. Animals 2025, 15, 3494. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233494

Wang Q, Huang H, Li C, Huang Z, Wu Z, Kong L, Zhao Z, Wang Z. The Role of Dietary Schizochytrium Powder in Chicken Production Performance, Egg Quality, and Antioxidant Status. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3494. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233494

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Qianbao, Huayun Huang, Chunmiao Li, Zhengyang Huang, Zhaolin Wu, Linglin Kong, Zhenhua Zhao, and Zhicheng Wang. 2025. "The Role of Dietary Schizochytrium Powder in Chicken Production Performance, Egg Quality, and Antioxidant Status" Animals 15, no. 23: 3494. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233494

APA StyleWang, Q., Huang, H., Li, C., Huang, Z., Wu, Z., Kong, L., Zhao, Z., & Wang, Z. (2025). The Role of Dietary Schizochytrium Powder in Chicken Production Performance, Egg Quality, and Antioxidant Status. Animals, 15(23), 3494. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233494