Comparative Effects of Aminophylline, Caffeine, and Doxapram in Hypoxic Neonatal Dogs Born by Cesarean Section

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Animals and Experimental Procedure

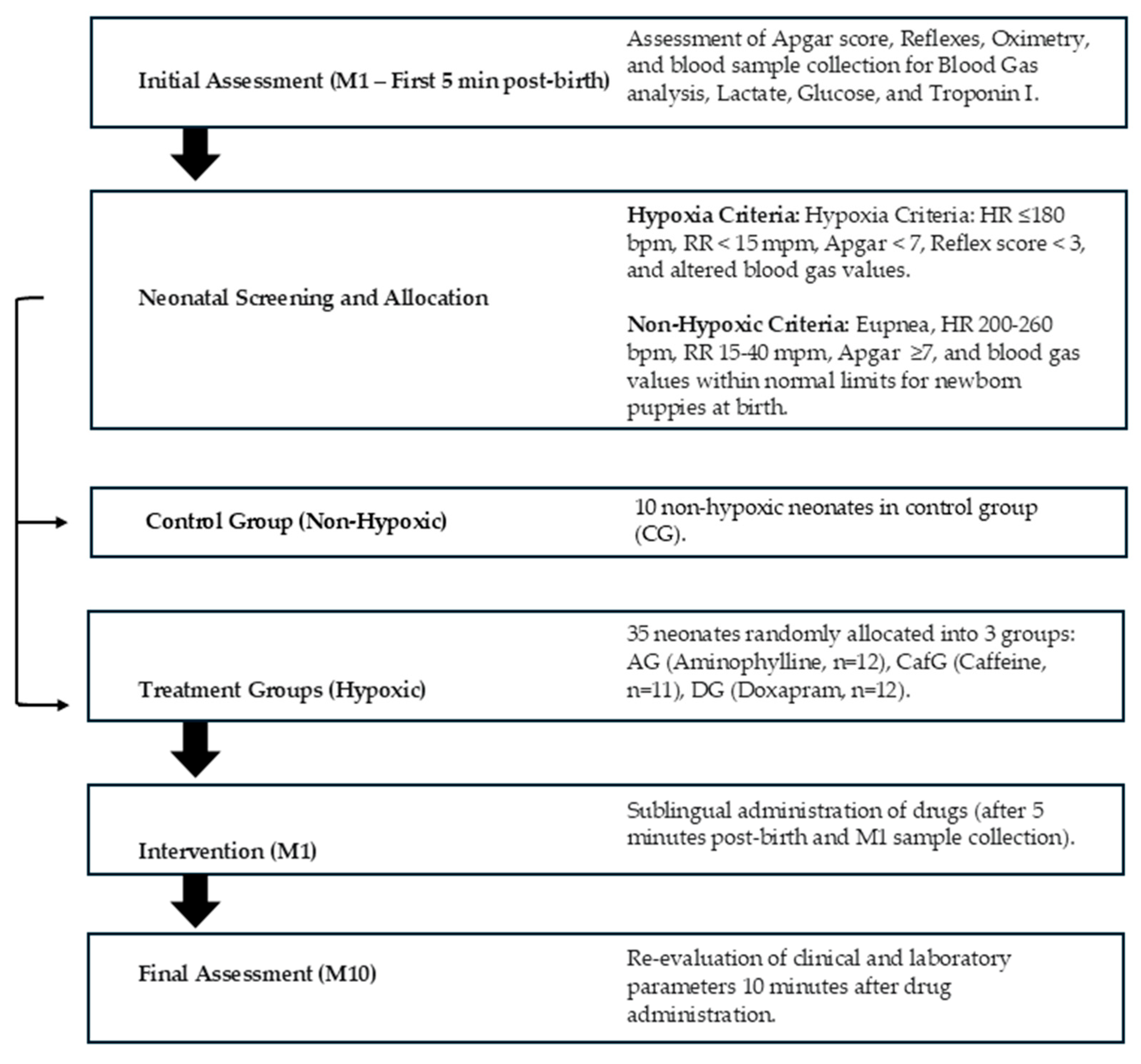

2.3. Grouping and Treatment Protocol

2.4. Clinical and Biochemical Parameters Evaluated

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AG | Aminophylline Group |

| CafG | Caffeine Group |

| DG | Doxapram Group |

| CG | Control Group |

| M1 | Five minutes after birth (before drug administration) |

| M10 | Ten minutes after drug administration |

| Δ | Difference between time points (M10 − M1) |

| bpm | Beats per minute |

| mov/min | Movements per minute |

| cTnI | Cardiac troponin I |

| pO2 | Partial pressure of oxygen |

| pCO2 | Partial pressure of carbon dioxide |

| BE | Base excess |

| NaHCO3 | Sodium bicarbonate |

| TCO2 | Total carbon dioxide |

| SO2 | Oxygen saturation |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| °C | Degrees Celsius |

| mmHg | Millimeters of mercury |

| ng/mL | Nanograms per milliliter |

| mg/dL | Milligrams per deciliter |

| mmol/L | Millimoles per liter |

| kg | Kilogram |

| g | Gram |

| mL | Milliliter |

| CEUA | Comissão de Ética no Uso de Animais (Animal Use Ethics Committee) |

| UNESP | Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” |

| FAPESP | Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo |

| CNPq | Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico |

References

- Vassalo, F.G.; Simões, C.R.B.; Sudano, M.J.; Prestes, N.C.; Lopes, M.D.; Chiacchio, S.B.; Lourenço, M.L.G. Topics in the routine assessment of newborn puppy viability. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2015, 30, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). World Health Statistics 2018: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272596/9789241565585-eng.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Mila, H.; Grellet, A.; Delebarre, M.; Mariani, C.; Feugier, A.; Chastant-Maillard, S. Monitoring of the newborn dog and prediction of neonatal mortality. Prev. Vet. Med. 2017, 143, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mila, H.; Grellet, A.; Feugier, A.; Chastant-Maillard, S. Differential impact of birth weight and early growth on neonatal mortality in puppies. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 93, 4436–4442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, R.A.; Almeida, L.L.; Rosa Filho, R.R.D.; Angrimani, D.S.R.; Brito, M.M.; Flores, R.B.; Vannucchi, C.I. Canine pulmonary clearance during feto-neonatal transition according to the type of delivery. Theriogenology 2024, 224, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, M.C.; Fusi, J. Biochemical factors affecting newborn survival in dogs and cats. Theriogenology 2023, 197, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.G.; Portari, G.V.; Lucio, C.F.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Veiga, G.L.; Vannucchi, C.I. The influence of the obstetrical condition on canine neonatal pulmonary functional competence. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2015, 25, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lúcio, C.F.; Silva, L.C.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Veiga, G.A.; Vannucchi, C.I. Acid–base changes in canine neonates following normal birth or dystocia. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2009, 44, 208–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, K.H.N.P.; Hibaru, V.Y.; Fuchs, K.M.; Correia, L.E.C.S.; Lopes, M.D.; Ferreira, J.C.P.; Souza, F.F.; Machado, L.H.A.; Chiacchio, S.B.; Lourenço, M.L.G. Use of cardiac troponin I (cTnI) levels to diagnose severe hypoxia and myocardial injury induced by perinatal asphyxia in neonatal dogs. Theriogenology 2022, 180, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, R.L.; Saunders, A.B.; Gordon, S.G.; Miller, M.W.; Fosgate, G.T.; Suchodolski, J.S.; Steiner, J.M. Biologic variability of cardiac troponin I in healthy dogs and dogs with different stages of myxomatous mitral valve disease using standard and high-sensitivity immunoassays. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2017, 46, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münnich, A. The pathological newborn in small animals: The neonate is not a small adult. Vet. Res. Commun. 2008, 32, S81–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münnich, A.; Küchenmeister, U. Causes, diagnosis and therapy of common diseases in neonatal puppies in the first days of life: Cornerstones of practical approach. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2014, 49, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boller, M.; Burkitt-Creedon, J.M.; Fletcher, D.J.; Byers, C.G.; Davidson, A.P.; Farrell, K.S.; Bassu, G.; Fausak, E.D.; Grundy, S.A.; Lopate, C.; et al. RECOVER Guidelines: Newborn Resuscitation in Dogs and Cats. Clinical Guidelines. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2025, 35 (Suppl. S1), S60–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boller, M.; Burkitt-Creedon, J.M.; Byers, C.G.; Fletcher, D.J.; Farrell, K.S.; Davidson, A.P.; Fricke, S.; Bassu, G.; Grundy, S.A.; Lopate, C.; et al. RECOVER Guidelines: Newborn Resuscitation in Dogs and Cats. Evidence and Knowledge Gap Analysis with Treatment Recommendations. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2025, 35 (Suppl. S1), 3–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakonidou, S.; Dhaliwal, J. The management of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome in preterm infants (European Consensus Guidelines—2013 Update). Arch. Dis. Child. Educ. Pract. 2015, 100, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.C.; Pompemayer, L.G.; Mata, L.B.S.C.; Alonso, D.C.; Borboleta, L.R. Efeitos da aminofilina e do doxapram em recém-nascidos advindos de cesariana eletiva em cadelas anestesiadas com midazolam, propofol e isofluorano. Rev. Ceres 2007, 54, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, B.; Roberts, R.S.; Davis, P.; Doyle, L.W.; Barrington, K.J.; Ohlsson, A. Caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 2112–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimokaze, T.; Toyoshima, K.; Shibasaki, J.; Itani, Y. Blood potassium and urine aldosterone after doxapram therapy for preterm infants. J. Perinatol. 2018, 38, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luvoni, G.C.; Beccaglia, M. The prediction of parturition date in canine pregnancy. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2006, 41, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siena, G.; Milani, C. Usefulness of Maternal and Fetal Parameters for the Prediction of Parturition Date in Dogs. Animals 2021, 11, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretzer, S.D. Medical management of canine and feline dystocia. Theriogenology 2008, 70, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antończyk, A.; Ochota, M. Is an epidural component during general anaesthesia for caesarean section beneficial for neonatal puppies’ health and vitality? Theriogenology 2022, 187, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, K.H.N.P.; Fuchs, K.M.; Hibaru, V.Y.; Correia, L.E.C.; Ferreira, J.C.P.; Souza, F.F.; Lourenço, M.L.G. Neonatal sepsis in dogs: Incidence, clinical aspects and mortality. Theriogenology 2022, 177, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, K.H.N.P.; Fuchs, K.M.; Mendonça, J.C.; Xavier, G.M.; Câmara, D.R.; Cruz, R.K.S.; Lourenço, M.L.G. Neonatal Clinical Assessment of the Puppy and Kitten: How to Identify Newborns at Risk? Animals 2024, 23, 3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veronesi, M.C.; Panzani, S.; Faustini, M.; Rota, A. An Apgar scoring system for routine assessment of newborn puppy viability and short-term survival prognosis. Theriogenology 2009, 72, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veronesi, M.C.; Faustini, M.; Probo, M.; Rota, A.; Fusi, J. Refining the APGAR score cutoff values and viability classes according to breed body size in newborn dogs. Animals 2022, 12, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traas, A.M. Resuscitation of canine and feline neonates. Theriogenology 2008, 70, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boller, M.; Burkitt-Creedon, J.M. Update on Newborn Resuscitation in Dogs and Cats. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2025, 55, 745–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, T.H.; Fretwell, S.; Bowden, R.S.; Coaicetto, F.; Irons, P.C.; Aleri, J.W.; Kordzakhia, N.; Page, S.W.; Musk, G.C.; Tuke, S.J.; et al. The effect of doxapram on survival and Apgar score in newborn puppies delivered by elective caesarean: A randomized controlled trial. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 46, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondal, A.Z.; Zulfiqar, H. Aminophylline. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545175/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Papich, M.G. Doxapram Hydrochloride. In Papich Handbook of Veterinary Drugs, 5th ed.; Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2021; pp. 306–307. [Google Scholar]

- Vliegenthart, R.J.; Ten Hove, C.H.; Onland, W.; van Kaam, A.H. Doxapram treatment for apnea of prematurity: A systematic review. Neonatology 2017, 111, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giguere, S.; Sanchez, L.C.; Shih, A. Comparison of the effects of caffeine and doxapram on respiratory and cardiovascular function in foals with induced respiratory acidosis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2007, 68, 1407–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giguere, S.; Slade, J.K.; Sanchez, L.C. Retrospective comparison of caffeine and doxapram for the treatment of hypercapnia in foals with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2008, 22, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balıkcı, E.; Yıldız, A. Effects on arterial blood gases and some clinical parameters of caffeine, atropine sulphate or doxapram hydrochloride in calves with neonatal asphyxia. Rev. Med. Vet. 2009, 160, 282–287. [Google Scholar]

- Swinbourne, A.M.; Kind, K.L.; Flinn, T.; Kleemann, D.O.; van Wettere, W.H.E.J. Caffeine: A potential strategy to improve survival of neonatal pigs and sheep. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 226, 106700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motwani, J.G.; Lipworth, B.J. Clinical pharmacokinetics of drugs administered buccally and sublingually. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1991, 21, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narang, N.; Sharma, J. Sublingual mucosa as a route for systemic drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 3 (Suppl. S2), 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Viana, F.A.B. Guia Terapêutico Veterinário, 5th ed.; CEM: Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter/Score | 0 | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mucous membrane color | Cyanotic | Pale | Pink |

| Heart rate | <100 bpm | <200 bpm | 200–260 bpm |

| Respiratory rate | Absent < 6 mpm | Weak and irregular <15 mpm (6–15) | Regular and rhythmic >15 mpm |

| Muscle tone | Flaccid | Some limb flexions | Flexion |

| Reflex irritability | Absent | Some movement | Clear crying |

| Indicator/ Score | 0 | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sucking | Absent | Poor | Strong |

| Rooting | Absent | Slow fitting of the snout within the circle | Immediate fitting of the snout within the circle |

| Righting | Absent (continued in the decubitus position) | Slow body repositioning | Immediate body repositioning |

| Parameter | Cesarean Section | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Hypoxemic Puppies | Hypoxemic Puppies | |

| pH | 7.2 | 7.1 |

| pCO2 (mmHg) | 49.3 | 64.4 |

| pO2 (mmHg) | 13.7 | 7.0 |

| HCO3 (mmol/L) | 23.2 | 25.7 |

| TCO2 (mM) | 25.1 | 28.2 |

| Base excess (mmol/L) | −5.1 | −4.2 |

| Lactate (mg/dL) | 3.9 | 4.8 |

| SO2 (%) | 19.6 | 8.6 |

| Peripheral SO2 (%) | 97.9 | 57.6 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 97.3 | 122.6 |

| Troponin I (ng/mL) | 0.05 | 0.15 |

| Variable | Mean ± SD or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of bitches | 14 |

| Maternal age (years) | 2.64 ± 0.93 |

| Maternal body weight (kg) | 12.64 ± 9.18 |

| Litter size (puppies per bitch) | 4.93 ± 3.63 (includes all live-born pups per bitch) |

| Total neonates’ puppies | 69 |

| Total neonates included | 45 |

| Neonatal birth weight (g) | 267.28 ± 97.34 |

| Neonatal rectal temperature at birth (°C) | 33.45 ± 1.65 |

| Sex distribution | ♂ 23 (51.1%); ♀ 22 (48.8%) |

| Early neonatal mortality (first hours) | 3 (7.0%) |

| Parameter | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Heart rate (bpm) | 196.0 ± 8.98 |

| Respiratory rate (movements/min) | 26.10 ± 6.74 |

| Apgar score | 10.0 ± 0.00 |

| Reflex score | 5.2 ± 0.78 |

| SpO2 (%) | 98.8 ± 0.42 |

| pH | 7.2 ± 0.09 |

| pCO2 (mmHg) | 48.53 ± 11.07 |

| pO2 (mmHg) | 15.73 ± 5.93 |

| Base excess (mmol/L) | −4.5 ± 3.17 |

| HCO3− (mmol/L) | 23.5 ± 2.8 |

| sO2 (%) | 20.60 ± 10.04 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 3.41 ± 1.45 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 93.5 ± 15.52 |

| Troponin I (ng/mL) | 0.05 ± 0.01 |

| Clinical Parameters | Aminophylline Group (n = 12) | Caffeine Group (n = 11) | Doxapram Group (n = 12) | p Intragroup | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M10 | M1 | M10 | M1 | M10 | ||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 153.83 ± 22.16 | 175.00 ± 16.72 | 147.09 ± 23.82 | 182.18 ± 12.82 | 127.38 ± 34.63 | 156.83 ± 29.48 | NS |

| Respiratory rate (mov/min) | 27.00 ± 11.43 | 23.41 ± 6.38 | 22.36 ± 11.12 | 25.63 ± 9.99 | 19.92 ± 6.75 | 24.75 ± 5.92 | NS |

| Apgar score | 5.50 ± 1.78 | 8.00 ± 1.12 | 4.18 ± 1.07 | 8.45 ± 1.50 | 4.69 ± 1.43 | 6.25 ± 1.96 | NS |

| Reflex score | 1.25 ± 1.42 | 3.75 ± 1.71 | 1.18 ± 1.16 | 3.36 ± 1.62 | 1.07 ± 0.95 | 3.72 ± 1.61 | NS |

| SpO2 (%) | 98.66 ± 1.15 | 99.00 ± 0.00 | 95.54 ± 8.35 | 98.63 ± 0.92 | 98.00 ± 3.31 | 98.91 ± 0.28 | NS |

| Group | n | Average (Δ) ± DP | Median | Q1–Q2 | Min–Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aminophylline group | 12 | 2.50 ± 1.31 | 2.00 | 1.50–3.50 | 1–5 |

| Caffeine * group | 11 | 4.27 ± 1.10 | 4.00 | 4.00–5.00 | 2–6 |

| Doxapram group | 12 | 1.64 ± 3.14 | 2.00 | 0.00–3.50 | 5–6 |

| Clinical Parameters | Aminophylline Group (n = 12) | Caffeine Group (n = 11) | Doxapram Group (n = 12) | p Intragroup | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M10 | M1 | M10 | M1 | M10 | ||

| pH | 7.05 ± 0.10 | 7.11 ± 0.08 | 7.02 ± 0.12 | 7.09 ± 0.09 | 6.92 ± 0.15 | 7.08 ± 0.18 | NS |

| pCO2 (mmHg) | 80.84 ± 13.83 | 66.80 ± 12.76 | 88.73 ± 22.02 | 66.08 ± 15.15 | 30.58 ± 13.01 | 66.55 ± 14.17 | NS |

| pO2 (mmHg) | 29.45 ± 13.35 | 39.66 ± 14.44 | 33.0 ± 14.41 | 55.18 ± 30.41 | 98.95 ± 18.60 | 52.0 ± 21.16 | NS |

| Base excess (mmol/L) | −8.51 ± 4.73 | −7.95 ± 4.05 | −7.75 ± 3.40 | −10.12 ± 4.04 | −11.8 ± 6.28 | −11.13 ± 6.14 | NS |

| HCO3− (mmol/L) | 22.64 ± 3.55 | 21.65 ± 3.64 | 23.20 ± 2.89 | 19.97 ± 3.28 | 21.10 ± 4.36 | 19.20 ± 3.44 | NS |

| sO2 (%) | 33.90 ± 23.30 | 50.26 ± 21.50 | 40.10 ± 23.43 | 63.56 ± 27.36 | 31.50 ± 22.54 | 66.85 ± 22.41 | NS |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 5.19 ± 1.73 | 5.65 ± 1.63 | 5.76 ± 1.50 | 6.73 ± 1.33 | 7.28 ± 3.18 | 7.16 ± 1.21 | NS |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 120.58 ± 57.83 | 120.41 ± 60.31 | 122.63 ± 48.30 | 120.81 ± 51.22 | 135.00 ±51.21 | 134.66 ± 48.35 | NS |

| Troponin I (ng/mL) | 0.07 ± 0.06 | 0.08 ± 0.05 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.08 ± 0.04 | 0.07 ± 0.04 | 0.07 ± 0.05 | NS |

| Study | Species/Condition | Drug(s)/Approach | Outcome Measure | Best Response | Notes/Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present study (2025) | Hypoxic canine neonates (cesarean) | Aminophylline vs. Caffeine vs. Doxapram | Δ Apgar (M10 − M1) | Caffeine | Caffeine showed the greatest clinical recovery; two deaths occurred in the doxapram group |

| Santos et al. (2007) [16] | Canine cesarean neonates | Aminophylline vs. Doxapram (sublingual & SC) | Apgar score | Aminophylline (sublingual) | Sublingual aminophylline led to faster Apgar recovery; doxapram was less consistent |

| Veronesi et al. (2009) [25] | Canine neonates in different types of delivery | No pharmacological intervention (vitality assessment) | Apgar and reflex recovery over time | -- | Routine Apgar evaluation of newborn dogs for assessing viability and determining survival prognoses |

| Schmidt et al. (2006) [17] | Preterm human neonates | Caffeine vs. Aminophylline | Apnea reduction & survival | Caffeine | Became gold standard in human neonatal therapy |

| Pereira et al. (2022) [9] | Hypoxic canine neonates | No drug (focus on hypoxia damage) | cTnI elevation, survival | -- | Hypoxia associated with myocardial injury; supports need for early intervention |

| Hyndman et al., 2023 [29] | Puppies delivered elective cesarian | Doxapram | Insufficient evidence | -- | insufficient evidence to conclude a difference in the probability of a puppy having an APGAR score |

| RECOVER Guidelines—Clinical (Boller et al., 2025) [13] | Canine & feline neonates | Standardized neonatal resuscitation algorithm | Viability restoration pathway | PPV + thermal + airway first | Drugs are adjuncts only when ventilation fails |

| RECOVER Guidelines—Evidence & Gaps (Boller et al., 2025) [14] | Evidence-based gap analysis | Comparative evidence review of stimulant drugs | Evidence strength levels | Caffeine considered promising | Aminophylline moderately supported; doxapram inconclusive; highlights need for comparative trials |

| Update on Newborn Resuscitation (Boller et al., 2025) [28] | Neonatal canine/feline resuscitation review | Summary of current neonatal stabilization strategies | Survival and revival prospects | Caffeine emphasized | Notes limited species-specific clinical trials on pharmacological stimulants |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mendonça, J.C.; Pereira, K.H.N.P.; Xavier, G.M.; Fuchs, K.d.M.; Faustino, T.G.; Codognoto, V.M.; Tsunemi, M.H.; Takahira, R.K.; Apparício, M.; Lourenço, M.L.G. Comparative Effects of Aminophylline, Caffeine, and Doxapram in Hypoxic Neonatal Dogs Born by Cesarean Section. Animals 2025, 15, 3485. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233485

Mendonça JC, Pereira KHNP, Xavier GM, Fuchs KdM, Faustino TG, Codognoto VM, Tsunemi MH, Takahira RK, Apparício M, Lourenço MLG. Comparative Effects of Aminophylline, Caffeine, and Doxapram in Hypoxic Neonatal Dogs Born by Cesarean Section. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3485. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233485

Chicago/Turabian StyleMendonça, Júlia Cosenza, Keylla Helena Nobre Pacífico Pereira, Gleice Mendes Xavier, Kárita da Mata Fuchs, Thaís Gomes Faustino, Viviane Maria Codognoto, Miriam Harumi Tsunemi, Regina Kiomi Takahira, Maricy Apparício, and Maria Lucia Gomes Lourenço. 2025. "Comparative Effects of Aminophylline, Caffeine, and Doxapram in Hypoxic Neonatal Dogs Born by Cesarean Section" Animals 15, no. 23: 3485. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233485

APA StyleMendonça, J. C., Pereira, K. H. N. P., Xavier, G. M., Fuchs, K. d. M., Faustino, T. G., Codognoto, V. M., Tsunemi, M. H., Takahira, R. K., Apparício, M., & Lourenço, M. L. G. (2025). Comparative Effects of Aminophylline, Caffeine, and Doxapram in Hypoxic Neonatal Dogs Born by Cesarean Section. Animals, 15(23), 3485. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233485