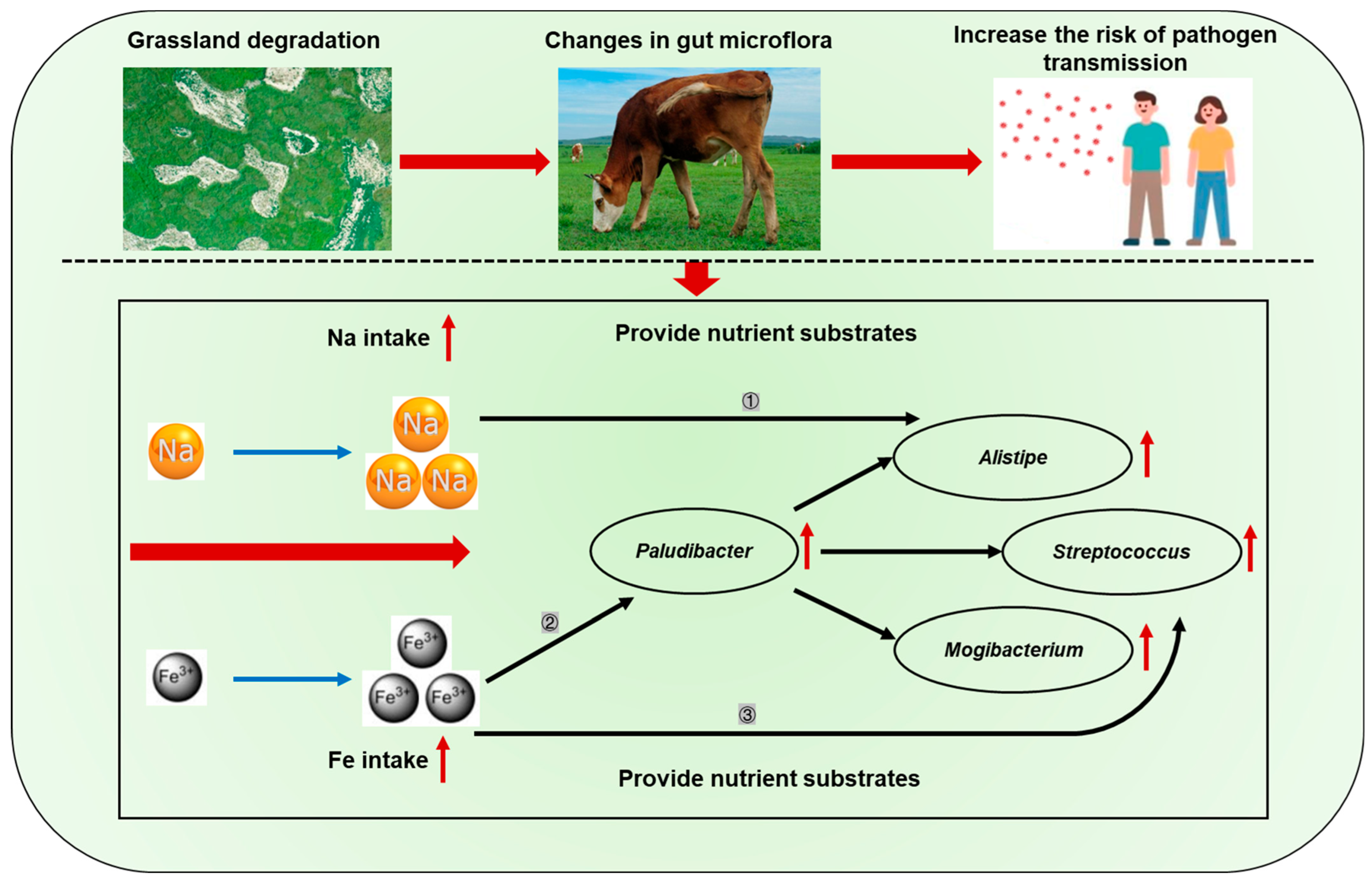

Grassland Saline-Alkaline Degradation-Induced Excessive Iron and Sodium Intake Potentially Increases the Transmission Risk of Fecal Pathogenic Bacteria in Cattle

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of Experiment 1

2.2. Design of Experiment 2

2.3. Monitoring of Plants Consumed by Cattle

2.4. Sample Collection

2.5. Analysis of the Nutritional Composition of Plants

2.6. Analysis of the Bacterial Community Composition in Feces

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

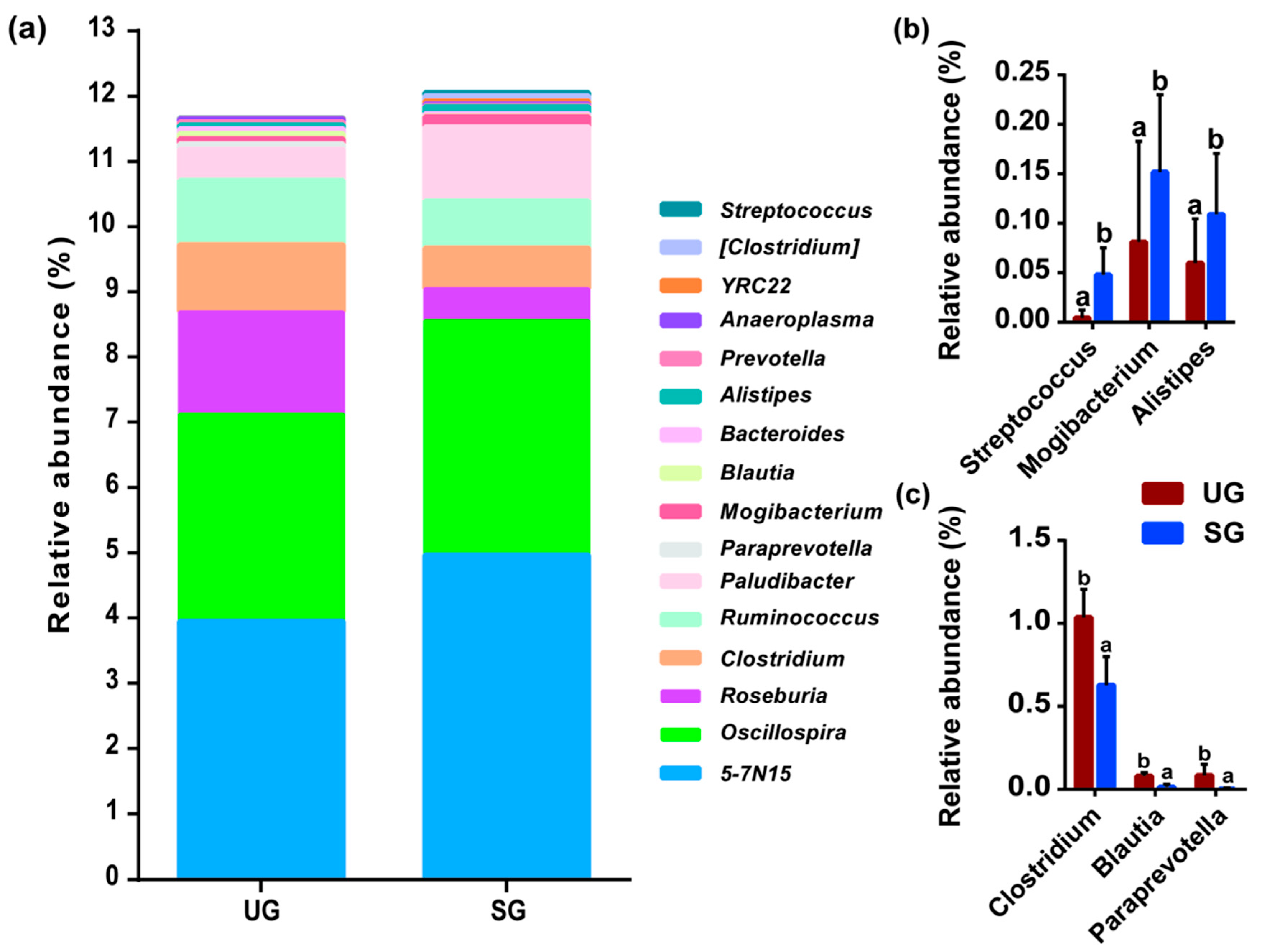

3.1. Variation in Fecal Bacterial Community

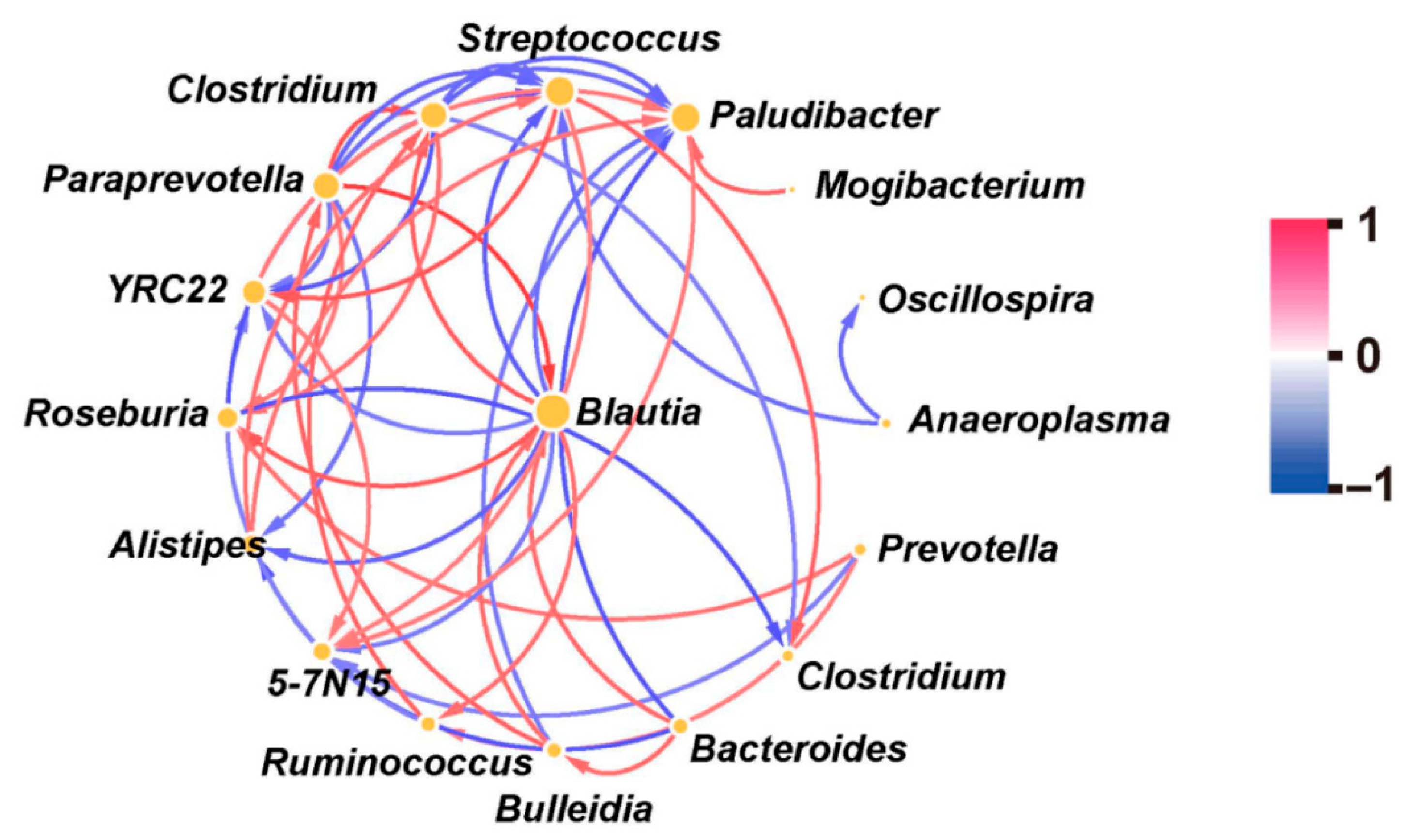

3.2. Correlation Among Various Bacteria

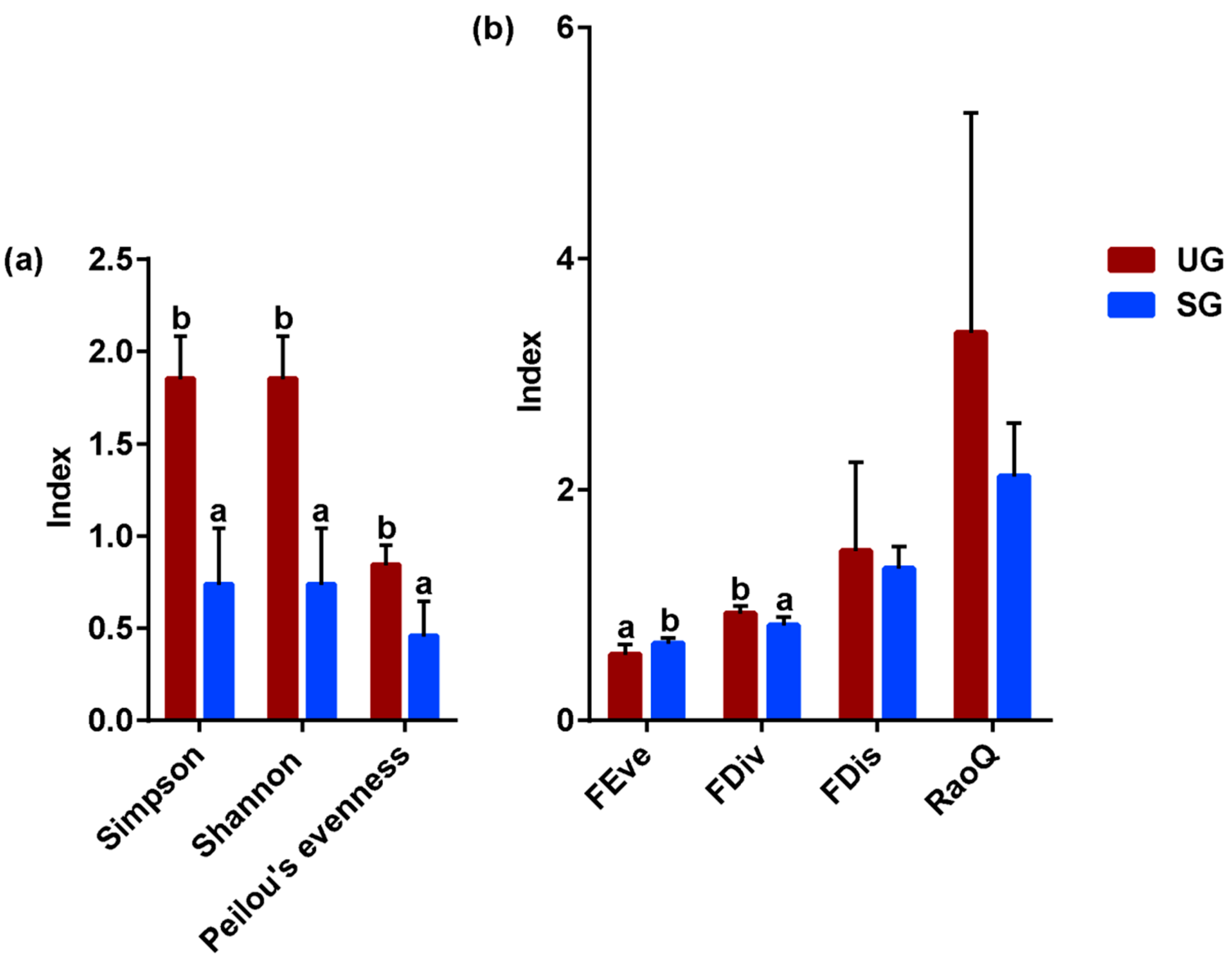

3.3. Foraging Diversity

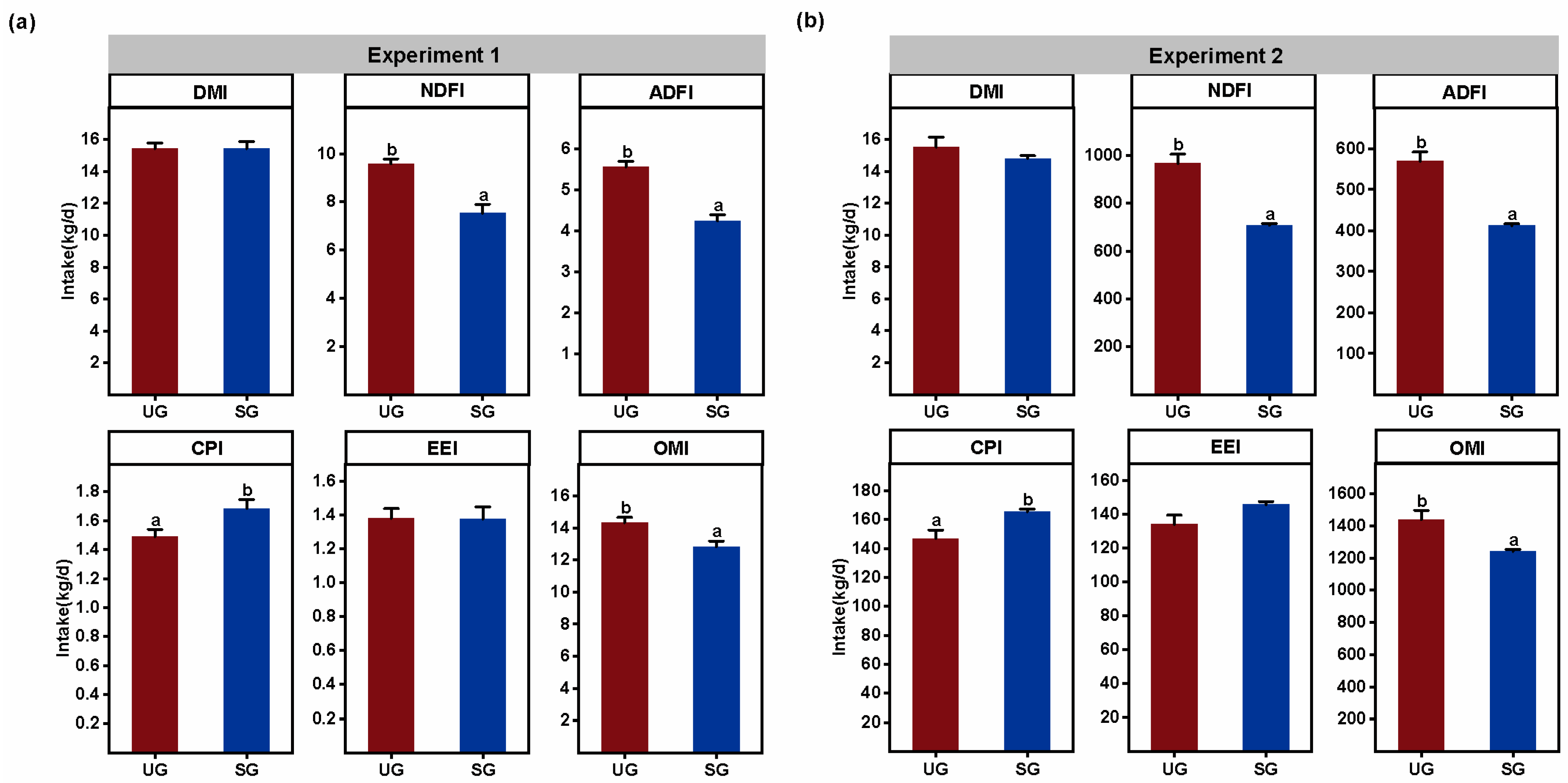

3.4. Proximate Nutrient Intake

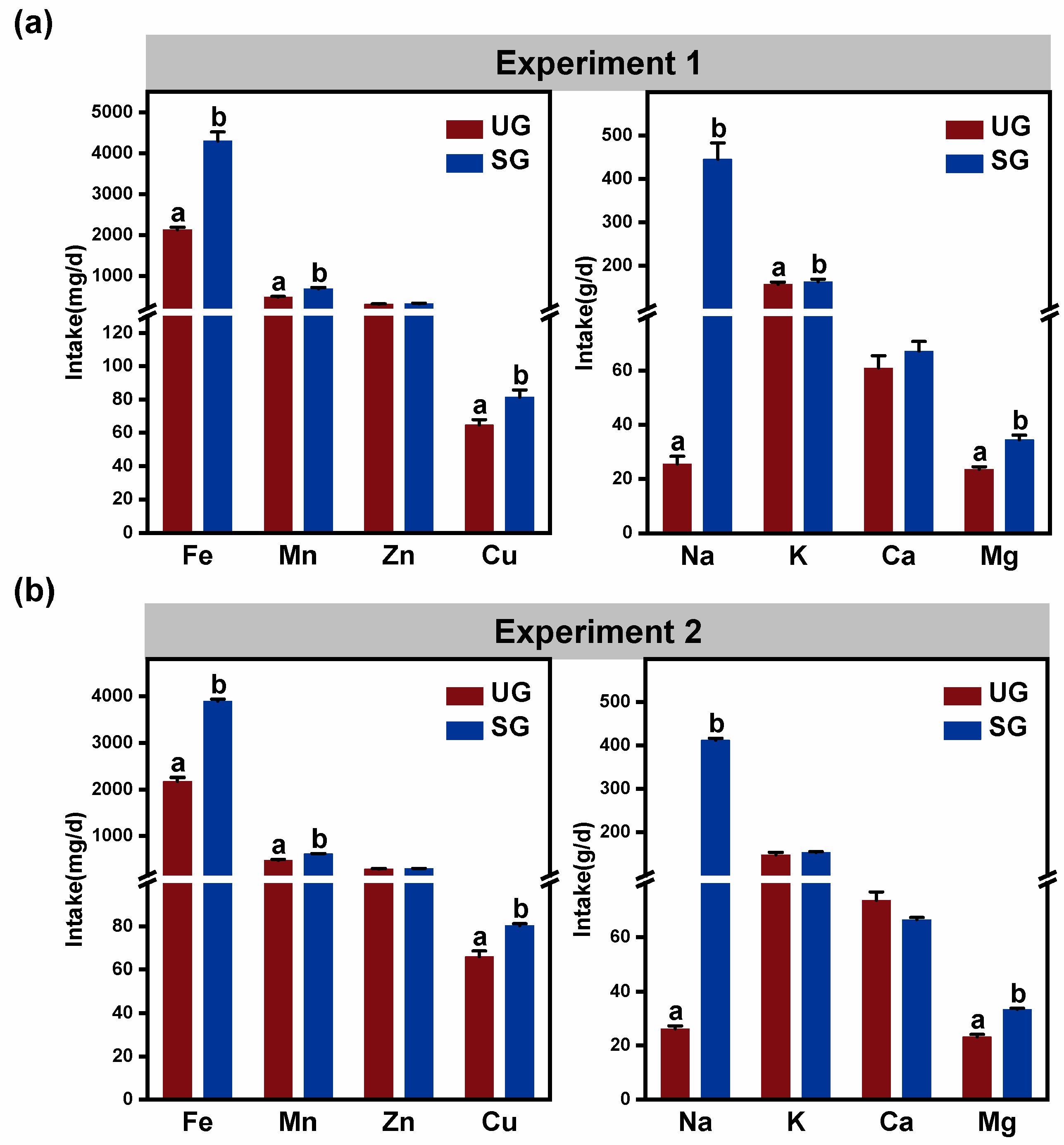

3.5. Mineral Element Intake

3.6. The Relative Importance of Various Factors for the Key Fecal Bacteria

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Desvars-Larrive, A.; Vogl, A.E.; Puspitarani, G.A.; Yang, L.; Joachim, A.; Käsbohrer, A. A One Health framework for exploring zoonotic interactions demonstrated through a case study. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyi-Loh, C.E.; Mamphweli, S.N.; Meyer, E.L.; Makaka, G.; Simon, M.; Okoh, A.I. An overview of the control of bacterial pathogens in cattle manure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.E.; Kim, M.; Bono, J.L.; Kuehn, L.A.; Benson, A.K. Meat science and muscle biology symposium: Escherichia coli O157: H7, diet, and fecal microbiome in beef cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 92, 1345–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, V.J.; Song, S.J.; Delsuc, F.; Prest, T.L.; Oliverio, A.M.; Korpita, T.M.; Alexiev, A.; Amato, K.R.; Metcalf, J.L.; Kowalewski, M.; et al. The effects of captivity on the mammalian gut microbiome. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2017, 57, 690–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparini, M.; Brambilla, G.; Menotta, S.; Albrici, G.; Avezzù, V.; Vitali, R.; Cavallini, D. Sustainable dairy farming and fipronil risk in circular feeds: Insights from an Italian case study. Food Addit. Contam. A 2024, 41, 1582–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, S.B.C.; Diugan, E.A. Microbiological air quality in tie-stall dairy barns and some factors thatinfluence it. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2011, 6, 6726–6734. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz, S.O.C.; Martínez-Olarte, R.; Navajas-Benito, E.V.; Alonso, C.A.; Hidalgo-Sanz, S.; Somalo, S.; Torres, C. Airborne dissemination of Escherichia coli in a dairy cattle farm and its environment. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 197, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bureau, B.T.P.L. Technique de Promotion Laitière; Le Logement du Tropeau Laitière; Editions France Agricole: Paris, France, 2001; p. 189. [Google Scholar]

- Brandl, H.F.-F.C.; Ziegler, D.; Mandal, J.; Stephan, R.; Lehner, A. Distribution and identificationof culturable airborne microorganisms in a Swiss milk processing facility. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curiel, G.J.; Van Eijk, H.M.J.; Lelieveld, H.L.M. Risk and control of airborne contamination. In Encyclopediaof Food Microbiology; Academic Press: London, UK, 2000; pp. 1816–1822. [Google Scholar]

- VanderWaal, K.; Gilbertson, M.; Okanga, S.; Allan, B.F.; Craft, M.E. Seasonality and pathogen transmission in pastoral cattle contact networks. R. Soc. Open. Sci. 2017, 4, 170808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.A.; Fox, N.J.; Marion, G.; Booth, N.J.; Morris, A.M.; Athanasiadou, S.; Hutchings, M.R. Animal behaviour packs a punch: From parasitism to production, pollution and prevention in grazing livestock. Animals 2024, 14, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardgett, R.D.; Bullock, J.M.; Lavorel, S.; Manning, P.; Schaffner, U.; Ostle, N.; Chomel, M.; Durigan, G.; LFry, E.; Johnson, D.; et al. Combatting global grassland deg-radation. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 720–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierickx, W.R. The salinity and alkalinity status of arid and semi-arid lands. Encycl. Land Use Land Cover. Soil Sci. 2009, 5, 163–189. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Xie, K.; Pan, Y.; Liu, F.; Hou, F. Effects of different fiber levels of energy feeds on rumen fermentation and the microbial community structure of grazing sheep. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ding, J.; Wang, Y.; Ge, X.; Lizaga, I.; Chen, X. Soil salinization in drylands: Measure, monitor, and manage. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 175, 113608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zhang, M.; Ding, S.; Liu, B.; Chang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L. Grassland degradation with saline-alkaline reduces more soil inorganic carbon than soil organic carbon storage. Ecol Indic. 2021, 131, 108194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, T.; Duan, X.; Zhang, S.; Chen, M.; Hou, H. The degradation of subalpine meadows significantly changed the soil microbiome. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 349, 108470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setia, R.; Gottschalk, P.; Smith, P.; Marschner, P.; Baldock, J.; Setia, D.; Smith, J. Soil salinity decreases global soil organic carbon stocks. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 465, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, K.M.; Rousk, J. Salt effects on the soil microbial decomposer community and their role in organic carbon cycling: A review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 81, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okur, B.; Örçen, N. Soil salinization and climate change. In Climate Change and Soil Interactions; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 331–350. [Google Scholar]

- Basnet, A.; Kilonzo-Nthenge, A. Antibiogram profiles of pathogenic and commensal bacteria in goat and sheep feces on smallholder farm. Front. Antibiot. 2024, 3, 1351725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N.R.; Whon, T.W.; Bae, J.W. Proteobacteria: Microbial signature of dysbiosis in gut microbiota. Trends Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäumler, A.J.S.V. Interactions between the microbiota and pathogenic bacteria in the gut. Nature 2016, 535, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folks, D.J.; Gann, K.; Fulbright, T.E.; Hewitt, D.G.; DeYoung, C.A.; Wester, D.B.; Echols, K.N.; Draeger, D.A. Drought but not population density influences dietary niche breadth in white-tailed deer in a semiarid environment. Ecosphere 2014, 5, art162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Peng, S.; Ciais, P.; Saunois, M.; Dangal, S.R.S.; Herrero, M.; Havlík, P.; Tian, H.; Bousquet, P. Revisiting enteric methane emissions from domestic ruminants and their δ13cCH4 source signature. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Rani, K.; Datt, C. Molecular link between dietary fibre, gut microbiota and health. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 6229–6237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.X.; Liu, C.L.; Ch, S.L. Distribution of crude fat for a halophyte (Suaeda glauca) growing in the Songnen grassland. In Proceedings of the World Grassland and Grassland Conference 2008, Hohhot, China, 29 June–5 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, M.K.; Ellermann, M. Long chain fatty acids and virulence repression in intestinal bacterial pathogens. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 928503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.T.S.; Cui, Z.; Zhang, Y. Response of soil properties and microbial communities to increasing salinization in the meadow grassland of northeast China. Microb. Ecol. 2021, 82, 722–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.X.; Zhou, D.W.; Zhao, C.S.; Wang, M.L.; Zhong, R.Z.; Liu, H.W. Evaluation of yield and chemical composition of a halophyte (Suaeda glauca) and its feeding value for lambs. Grass Forage Sci. 2012, 67, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balique, F.; Lecoq, H.; Raoult, D.; Colson, P. Can plant viruses cross the kingdom border and be pathogenic to humans? Viruses 2015, 7, 2074–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Liu, L.; Han, P.; Gong, X.; Zhang, Q. Accuracy of vegetation indices in assessing different grades of grassland desertification from UAV. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, N.; Hassani, A.; Sahimi, M. Multi-scale soil salinization dynamics from global to pore scale: A review. Rev. Geophys. 2024, 62, e2023RG000804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Song, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, T.; Zhao, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, L. Grassland degradation induces high dietary niche overlap between two common livestock: Cattle and sheep. J. Sustain. Agric. Environ. 2023, 2, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Song, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yue, Y.; Yu, H.; Meng, H.; Wang, L. Plant diversity expands dietary niche breadth but facilitates dietary niche partitioning of co-occurring cattle and sheep. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 385, 109566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odadi, W.O.; Kimuyu, D.M.; Sensenig, R.L.; Veblen, K.E.; Riginos, C.; Young, T.P. Fire-induced negative nutritional outcomes for cattle when sharing habitat with native ungulates in an African savanna. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 54, 935–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, D.L.; Zeng, D.H.; Li, Y.X.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y. Foraging responses of sheep to plant spatial micro-patterns can cause diverse associational effects of focal plant at individual and population levels. J. Anim. Ecol. 2018, 87, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wen, Z.; Wei, S.; Lian, J.; Ye, W. Functional diversity and its influencing factors in a subtropical forest community in China. Forests 2022, 13, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldsine, P.; Abeyta, C.; Andrews, W.H. AOAC International methods committee guidelines for validation of qualitative and quantitative food microbiological official methods of analysis. J. AOAC Int. 2002, 85, 1187–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, P.V.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysac-charides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniek, H.; Wójciak, R.W. The combined effects of iron excess in the diet and chromium (III) supplementation on the iron and chromium status in female rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2018, 184, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Liu, X.L.; Chang, S.H.; Zhang, C.; Du, W.C.; Hou, F.J. Efects of Cistanche deserticola addition in the diet on ruminal microbiome and fermentation parameters of grazing sheep. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 840725. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, R.C.; Haas, B.J.; Clemente, J.C.; Quince, C.; Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2194–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2460–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, D.; Price, M.N.; Goodrich, J.; Nawrocki, E.P.; DeSantis, T.Z.; Probst, A.; Andersen, G.L.; Knight, R.; Hugenholtz, P. An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. ISME J. 2012, 6, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.; Lipman, D. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dini, F.M.; Jacinto, J.G.; Cavallini, D.; Beltrame, A.; Del Re, F.S.; Abram, L.; Galuppi, R. Observational longitudinal study on Toxoplasma gondii infection in fattening beef cattle: Serology and associated haematological findings. Parasitol. Res. 2024, 123, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.; Batool, A.; Arif, S. Healthy cattle microbiome and dysbiosis in diseased phenotypes. Ruminants 2022, 2, 134–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B.J.; Wearsch, P.A.; Veloo, A.C.; Rodriguez-Palacios, A. The genus Alistipes: Gut bacteria with emerging implications to inflammation, cancer, and mental health. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, F.; Ling, Z.; Tong, X.; Xiang, C. Human intestinal lumen and mucosa-associated microbiota in patients with colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Cho, J.H.; Song, M.; Cho, J.H.; Kim, S.; Kim, E.S.; Keum, G.B.; Kim, H.B.; Lee, J.H. Evaluating the prevalence of foodborne pathogens in livestock using metagenomics approach. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 31, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, J.N.; Palma, T.; Ribeiro, G.S.; Pinheiro, R.M.; Ribeiro, C.T.; Cordeiro, S.M.; Filho, H.d.S.; Moschioni, M.; Thompson, T.A.; Spratt, B.; et al. Transmission of Streptococcus pneumoniae in an urban slum community. J. Infect. 2008, 57, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avire, N.J.; Whiley, H.; Ross, K. A review of Streptococcus pyogenes: Public health risk factors, prevention and control. Pathogens 2021, 10, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Gimenez, G.; Lagier, J.C.; Robert, C.; Raoult, D.; Fournier, P.E. Genome sequence and description of Alistipes senegalensis sp. nov. Stand. Genomic. Sci. 2012, 6, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnicar, F.; Manara, S.; Zolfo, M.; Truong, D.T.; Scholz, M.; Armanini, F.; Ferretti, P.; Gorfer, V.; Pedrotti, A.; Tett, A.; et al. Studying vertical microbiome transmission from mothers to infants by strain-level metagenomic profiling. MSystems 2017, 2, e00164-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagier, J.C.; Armougom, F.; Mishra, A.K.; Nguyen, T.T.; Raoult, D.; Fournier, P.E. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Alistipes timonensis sp. nov. Stand. Genomic Sci. 2012, 6, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, P.; Zhang, K.; Ma, X.; He, P. Clostridium species as probiotics: Potentials and challenges. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechno. 2020, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Mao, B.; Gu, J.; Wu, J.; Cui, S.; Wang, G. Blautia—A new functional genus with potential probiotic properties? Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1875796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Watanabe, E.; Kawashima, Y.; Plichta, D.R.; Wang, Z.; Ujike, M.; Honda, K. Identification of trypsin-degrading commensals in the large intestine. Nature 2022, 609, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolnick, D.I.; Snowberg, L.K.; Hirsch, P.E.; Lauber, C.L.; Knight, R.; Caporaso, J.G.; Svanbäck, R. Individuals’ diet diversity influences gut microbial diversity in two freshwater fish (Threespine stickleback and Eurasian perch). Ecol. Lett. 2014, 17, 979–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, T.; Beasley, D.E.; Heděnec, P.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, S.; Li, X. Diet diversity is associated with beta but not alpha diversity of Pika gut microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Qu, J.; Li, T.; Wirth, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, X. Diet simplification selects for high gut microbial diversity and strong fermenting ability in high-altitude Pikas. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2018, 102, 6739–6751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.W.; Xiong, B.H.; Li, K.; Zhou, D.W.; Lv, M.B.; Zhao, J.S. Effects of Suaeda glauca crushed seed on rumen microbial populations, ruminal fermentation, methane emission, and growth performance in Ujumqin lambs. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2015, 210, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Biswas, D. Short chain and polyunsaturated fatty acids in host gut health and foodborne bacterial pathogen inhibition. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2017, 57, 3987–4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leedle, J.A.; Greening, R.C. Postprandial changes in methanogenic and acidogenic bacteria in the rumens of steers fed high-or low-forage diets once daily. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1988, 54, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saro, C.; Ranilla, M.J.; Tejido, M.L.; Carro, M.D. Influence of forage type in the diet of sheep on rumen microbiota and fermentation characteristics. Livest. Sci. 2014, 160, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmanand, B.A.; Kellingray, L.; Le Gall, G.; Basit, A.W.; Fairweather-Tait, S.; Narbad, A. A decrease in iron availability to human gut microbiome reduces the growth of potentially pathogenic gut bacteria; an in vitro colonic fermentation study. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 67, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, B.; Li, H. Gut microbiota and iron: The crucial actors in health and disease. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, J.R.; Laakso, H.A.; Heinrichs, D.E. Iron acquisition strategies of bacterial pathogens. In Virulence Mechanisms of Bacterial Pathogens; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 43–85. [Google Scholar]

- Zughaier, S.M.; Cornelis, P. Role of Iron in bacterial pathogenesis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, H. Effects of over-load iron on nutrient digestibility, haemato-biochemistry, rumen fermentation and bacterial communities in sheep. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 104, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, R.M.; Schwaiger, T.; Penner, G.B.; Beauchemin, K.A.; Forster, R.J.; McKinnon, J.J.; McAllister, T.A. Characterization of the core rumen microbiome in cattle during transition from forage to concentrate as well as during and after an acidotic challenge. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassat, J.E.; Skaar, E.P. Iron in infection and immunity. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 13, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, F.; Womack, E.; Vidal, J.E.; Le Breton, Y.; McIver, K.S.; Pawar, S.; Eichenbaum, Z. Hemoglobin stimulates vigorous growth of Streptococcus pneumoniae and shapes the pathogen’s global transcriptome. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirigliano, E.; Saint, A.; Pei, L.X.; Wong, C.W.; Wang, S.; Fischer, J.A.; Kroeun, H.; Karakochuk, C.D. Iron supplementation with ferrous sulfate or ferrous bisglycinate for 12 weeks does not influence Group B Streptococcus colonization in Cambodian women: A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. J. Nutr. 2025, in press. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamad, I.; Cardilli, A.; Côrte-Real, B.F.; Dyczko, A.; Vangronsveld, J.; Kleinewietfeld, M. High-salt diet induces depletion of lactic acid-producing bacteria in murine gut. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Key Bacteria | Variable | DF | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paludibacter | Fe | 4 | 196.67 | <0.01 |

| Cu | 4 | 0.50 | 0.52 | |

| Fe | 4 | 249.54 | 0.05 | |

| Mg | 4 | 1.97 | 0.23 | |

| Fe | 4 | 260.34 | <0.01 | |

| Simpson index | 4 | 2.28 | 0.21 | |

| Streptococcus | Fe | 4 | 51.08 | <0.01 |

| Cu | 4 | 1.04 | 0.37 | |

| Fe | 4 | 54.1 | <0.01 | |

| Mg | 4 | 1.53 | 0.28 | |

| Fe | 4 | 38.12 | <0.01 | |

| Simpson index | 4 | 0.04 | 0.84 | |

| Alistipes | Na | 4 | 177.87 | <0.01 |

| Cu | 4 | 9.19 | 0.11 | |

| Na | 4 | 115.61 | <0.01 | |

| Mg | 4 | 4.51 | 0.10 | |

| Na | 4 | 61.85 | 0.02 | |

| Simpson index | 4 | 0.49 | 0.52 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Gao, B.; Ma, G.; Xu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, X. Grassland Saline-Alkaline Degradation-Induced Excessive Iron and Sodium Intake Potentially Increases the Transmission Risk of Fecal Pathogenic Bacteria in Cattle. Animals 2025, 15, 3484. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233484

Wang Y, Gao B, Ma G, Xu M, Zhou Y, Jiang X. Grassland Saline-Alkaline Degradation-Induced Excessive Iron and Sodium Intake Potentially Increases the Transmission Risk of Fecal Pathogenic Bacteria in Cattle. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3484. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233484

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yizhen, Bingnan Gao, Guangming Ma, Man Xu, Yu Zhou, and Xin Jiang. 2025. "Grassland Saline-Alkaline Degradation-Induced Excessive Iron and Sodium Intake Potentially Increases the Transmission Risk of Fecal Pathogenic Bacteria in Cattle" Animals 15, no. 23: 3484. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233484

APA StyleWang, Y., Gao, B., Ma, G., Xu, M., Zhou, Y., & Jiang, X. (2025). Grassland Saline-Alkaline Degradation-Induced Excessive Iron and Sodium Intake Potentially Increases the Transmission Risk of Fecal Pathogenic Bacteria in Cattle. Animals, 15(23), 3484. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233484