Molecular Regulatory Mechanisms of Mammary Gland Development: A Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mammary Gland Development

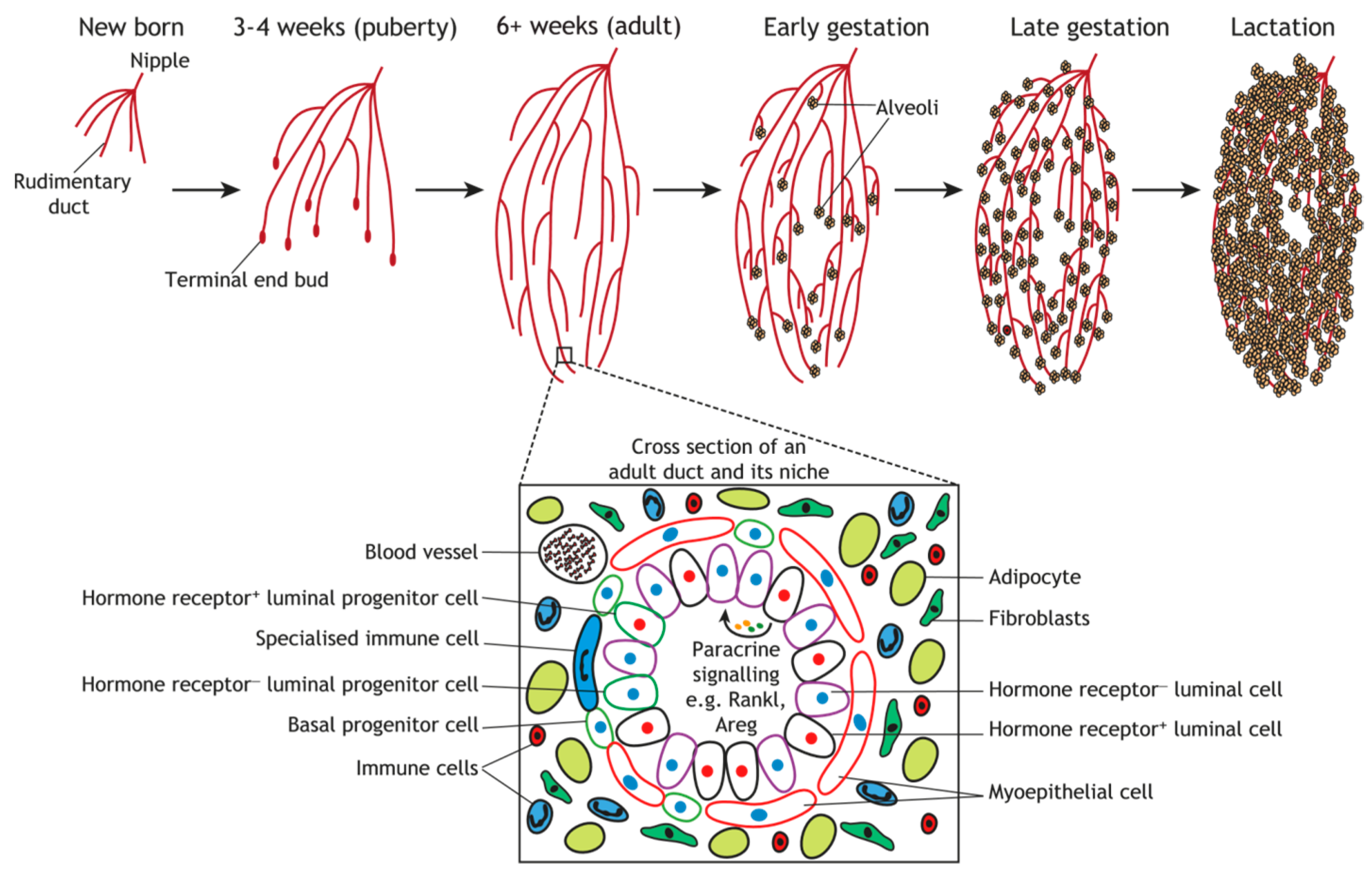

2.1. Composition and Structure of the Mammary Gland

2.2. Developmental Stages of the Mammary Gland

3. Regulatory Mechanisms of Embryonic Mammary Gland Development

4. Regulatory Mechanisms in Pubertal Mammary Gland Development

5. Regulatory Mechanisms of Mammary Gland Development During Pregnancy

6. Mammary Gland Development During Lactation

7. Mammary Gland Development During the Dry Period

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Biswas, S.K.; Banerjee, S.; Baker, G.W.; Kuo, C.Y.; Chowdhury, I. The Mammary Gland: Basic Structure and Molecular Signaling during Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, R.; Wu, Z.; Hou, Y.; Bazer, F.W.; Wu, G. Amino acids and mammary gland development: Nutritional implications for milk production and neonatal growth. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannan, F.M.; Elajnaf, T.; Vandenberg, L.N.; Kennedy, S.H.; Thakker, R.V. Hormonal regulation of mammary gland development and lactation. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2023, 19, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias, H.; Hinck, L. Mammary gland development. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2012, 1, 533–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaswal, S.; Jena, M.K.; Anand, V.; Jaswal, A.; Kancharla, S.; Kolli, P.; Mandadapu, G.; Kumar, S.; Mohanty, A.K. Critical Review on Physiological and Molecular Features during Bovine Mammary Gland Development: Recent Advances. Cells 2022, 11, 3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.A. Phosphoproteomics of Mammary Gland During Different Stages of Development and Its Role in Lactation. Ph.D. Thesis, National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wysolmerski, J.J. The Role of PTHrP in Mammary Gland Development and Tumorigenesis; U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command: Fort Detrick, MD, USA, 2000; Final Report, Award No. DAMD17-96-1-6198.

- Gjorevski, N.; Nelson, C.M. Integrated morphodynamic signalling of the mammary gland. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svennersten-Sjaunja, K.; Olsson, K. Endocrinology of milk production. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2005, 29, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanigan, F.; O’connor, D.; Martin, F.; Gallagher, W. Common Molecular Mechanisms of Mammary Gland Development and Breast Cancer: Molecular links between mammary gland development and breast cancer. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 3159–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, M.K.; Khan, F.B.; Ali, S.A.; Abdullah, A.; Sharma, A.K.; Yadav, V.; Kancharla, S.; Kolli, P.; Mandadapu, G.; Sahoo, A.K.; et al. Molecular complexity of mammary glands development: A review of lactogenic differentiation in epithelial cells. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2023, 51, 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSherry, E.; Donatello, S.; Hopkins, A.; McDonnell, S. Common Molecular Mechanisms of Mammary Gland Development and Breast Cancer: Molecular basis of invasion in breast cancer. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 3201–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oftedal, O.T. The mammary gland and its origin during synapsid evolution. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2002, 7, 225–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oftedal, O.T.; Dhouailly, D. Evo-devo of the mammary gland. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2013, 18, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visvader, J.E. Keeping abreast of the mammary epithelial hierarchy and breast tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 2563–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streuli, C.H. Cell adhesion in mammary gland biology and neoplasia. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2003, 8, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muschler, J.; Streuli, C.H. Cell-matrix interactions in mammary gland development and breast cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2, a003202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternlicht, M.D. Key stages in mammary gland development: The cues that regulate ductal branching morphogenesis. Breast Cancer Res. 2005, 8, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V. Age Related Histomorphological and Histochemical Studies on Mammary Gland of Goat. Ph.D. Thesis, Guru Angad Dev Veterinary and Animal Sciences University Ludhiana, Ludhiana, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ALsadi, S.; Fadeal, T. Anatomical and histological study in the udder of local Iraqi cattle (Bovidae caprinae). Basrah J. Vet. Res 2018, 17, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lérias, J.R.; Hernández-Castellano, L.E.; Suárez-Trujillo, A.; Castro, N.; Pourlis, A.; Almeida, A.M. The mammary gland in small ruminants: Major morphological and functional events underlying milk production–A review. J. Dairy Res. 2014, 81, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Kumar, M.; Sathapathy, S.; Singh, K.; Chaurasia, D.; Lade, D.; Verma, A. A comprehensive review of the gross anatomy of the mammary gland in domestic animals. e-planet 2024, 22, 171–175. [Google Scholar]

- Bistoni, G.; Farhadi, J. Anatomy and physiology of the breast. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Approaches Tech. 2015, 477–485. [Google Scholar]

- McNally, S.; Stein, T. Overview of mammary gland development: A comparison of mouse and human. In Mammary Gland Development: Methods and Protocols; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wagstrom, E.A.; Yoon, K.-J.; Zimmerman, J.J. Immune components in porcine mammary secretions. Viral Immunol. 2000, 13, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, A.J.; Hovey, R.C. Development of the mammary glands and its regulation: How not all species are equal. Anim. Front. 2023, 13, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yart, L.; Lollivier, V.; Marnet, P.G.; Dessauge, F. Role of ovarian secretions in mammary gland development and function in ruminants. Animal 2014, 8, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, M.K.; Mohanty, A.K. New insights of mammary gland during different stages of development. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2017, 10, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Borellini, F.; Oka, T. Growth control and differentiation in mammary epithelial cells. Environ. Health Perspect. 1989, 80, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Robinson, G.W. Cooperation of signalling pathways in embryonic mammary gland development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007, 8, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, N.J.; Smith, G.H.; Lawrence, E.; Barrett, J.C.; Salomon, D.S. Identification of stem cell units in the terminal end bud and duct of the mouse mammary gland. BioMed Res. Int. 2001, 1, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowson, A.R.; Daniels, K.M.; Ellis, S.E.; Hovey, R.C. Growth and development of the mammary glands of livestock: A veritable barnyard of opportunities. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2012, 23, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, J.C. Proceedings: Hormonal regulation of breast development and activity. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1974, 63, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warburton, D. Conserved Mechanisms in the Formation of the Airways and Alveoli of the Lung. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 662059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadar, M.; Mireşan, V.; Lujerdean, A.; Răducu, C. Mammary gland histological structure in relation with milk production in sheep. Sci. Pap. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2012, 45, 146. [Google Scholar]

- Spina, E.; Cowin, P. Embryonic mammary gland development. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 114, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltmaat, J.M.; Mailleux, A.A.; Thiery, J.P.; Bellusci, S. Mouse embryonic mammogenesis as a model for the molecular regulation of pattern formation. Differ. Rev. 2003, 71, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, G.; Atkinson, B.; Robertson, H. Development of the bovine placentome during the second month of gestation. Reproduction 1979, 55, 173-NP. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, S.; Martin, F. Molecular regulators of pubertal mammary gland development. Ann. Med. 2011, 43, 212–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howlin, J.; McBryan, J.; Martin, F. Pubertal mammary gland development: Insights from mouse models. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2006, 11, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paine, I.S.; Lewis, M.T. The Terminal End Bud: The Little Engine that Could. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2017, 22, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, S. Endocrine events involved in puberty: A revisit to existing knowledge. Life Sci. 2020, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akers, R.M. Lactation and the Mammary Gland; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- da Silveira Sa, R.d.C.; dos Santos Silva, V.K. Lactation: Natural Processes, Physiological Responses and Role in Maternity; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2012; akusher-lib. ru, 99. [Google Scholar]

- Napso, T.; Yong, H.E.J.; Lopez-Tello, J.; Sferruzzi-Perri, A.N. The Role of Placental Hormones in Mediating Maternal Adaptations to Support Pregnancy and Lactation. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.J.; Faria, T.N.; Roby, K.F.; Deb, S. Pregnancy and the prolactin family of hormones: Coordination of anterior pituitary, uterine, and placental expression. Endocr. Rev. 1991, 12, 402–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-González, G.L.; Bautista, C.J.; Rojas-Torres, K.I.; Nathanielsz, P.W.; Zambrano, E. Importance of the lactation period in developmental programming in rodents. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, H.; Smith, R.; Royal, M.; Knight, C.; Sheldon, I. The high-producing dairy cow and its reproductive performance. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2007, 42, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.J.; Kreuzaler, P.A. Remodeling mechanisms of the mammary gland during involution. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2011, 55, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.J.; Khaled, W.T. Mammary development in the embryo and adult: New insights into the journey of morphogenesis and commitment. Development 2020, 147, dev169862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vang, A.L.; Dorea, J.R.R.; Hernandez, L.L. Graduate Student Literature Review: Mammary gland development in dairy cattle-Quantifying growth and development. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 11611–11620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurley, W.L. Review: Mammary gland development in swine: Embryo to early lactation. Animal 2019, 13, s11–s19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailleux, A.A.; Spencer-Dene, B.; Dillon, C.; Ndiaye, D.; Savona-Baron, C.; Itoh, N.; Kato, S.; Dickson, C.; Thiery, J.P.; Bellusci, S. Role of FGF10/FGFR2b signaling during mammary gland development in the mouse embryo. Development 2002, 129, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowin, P.; Wysolmerski, J. Molecular mechanisms guiding embryonic mammary gland development. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2, a003251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, B.; Ashworth, A. Signalling pathways implicated in early mammary gland morphogenesis and breast cancer. PLoS Genet. 2006, 2, e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiremath, M.; Wysolmerski, J. Parathyroid hormone-related protein specifies the mammary mesenchyme and regulates embryonic mammary development. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2013, 18, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, K.M.; Booth, B.W.; Hendrix, M.J.; Salomon, D.S.; Strizzi, L. ErbB/EGF signaling and EMT in mammary development and breast cancer. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2010, 15, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisken, C.; Heineman, A.; Chavarria, T.; Elenbaas, B.; Tan, J.; Dey, S.K.; McMahon, J.A.; McMahon, A.P.; Weinberg, R.A. Essential function of Wnt-4 in mammary gland development downstream of progesterone signaling. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.W.; Kim, J.Y.; Song, S.J.; Farrell, E.; Eblaghie, M.C.; Kim, H.J.; Tickle, C.; Jung, H.S. Molecular interactions between Tbx3 and Bmp4 and a model for dorsoventral positioning of mammary gland development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 16788–16793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phippard, D.J.; Weber-Hall, S.J.; Sharpe, P.T.; Naylor, M.S.; Jayatalake, H.; Maas, R.; Woo, I.; Roberts-Clark, D.; Francis-West, P.H.; Liu, Y.H.; et al. Regulation of Msx-1, Msx-2, Bmp-2 and Bmp-4 during foetal and postnatal mammary gland development. Development 1996, 122, 2729–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michno, K.; Boras-Granic, K.; Mill, P.; Hui, C.C.; Hamel, P.A. Shh expression is required for embryonic hair follicle but not mammary gland development. Dev. Biol. 2003, 264, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.Y.; Sun, L.; Veltmaat, J.M. Hedgehog and Gli signaling in embryonic mammary gland development. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2013, 18, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eblaghie, M.C.; Song, S.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Akita, K.; Tickle, C.; Jung, H.S. Interactions between FGF and Wnt signals and Tbx3 gene expression in mammary gland initiation in mouse embryos. J. Anat. 2004, 205, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uyttendaele, H.; Soriano, J.V.; Montesano, R.; Kitajewski, J. Notch4 and Wnt-1 proteins function to regulate branching morphogenesis of mammary epithelial cells in an opposing fashion. Dev. Biol. 1998, 196, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fata, J.E.; Kong, Y.Y.; Li, J.; Sasaki, T.; Irie-Sasaki, J.; Moorehead, R.A.; Elliott, R.; Scully, S.; Voura, E.B.; Lacey, D.L.; et al. The osteoclast differentiation factor osteoprotegerin-ligand is essential for mammary gland development. Cell 2000, 103, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickenden, J.A.; Watson, C.J. Key signalling nodes in mammary gland development and cancer. Signalling downstream of PI3 kinase in mammary epithelium: A play in 3 Akts. Breast Cancer Res. 2010, 12, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, M.; Abe, C.; Wakinaga, S.; Sakane, K.; Yumiketa, Y.; Taguchi, Y.; Matsumura, T.; Ishikawa, K.; Fujimoto, J.; Semba, K.; et al. TRAF6 maintains mammary stem cells and promotes pregnancy-induced mammary epithelial cell expansion. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavitra, E.; Kancharla, J.; Gupta, V.K.; Prasad, K.; Sung, J.Y.; Kim, J.; Tej, M.B.; Choi, R.; Lee, J.H.; Han, Y.K.; et al. The role of NF-κB in breast cancer initiation, growth, metastasis, and resistance to chemotherapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 163, 114822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahar, M.E.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.R. Targeting the RAS/RAF/MAPK pathway for cancer therapy: From mechanism to clinical studies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whyte, J.; Bergin, O.; Bianchi, A.; McNally, S.; Martin, F. Key signalling nodes in mammary gland development and cancer. Mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling in experimental models of breast cancer progression and in mammary gland development. Breast Cancer Res. 2009, 11, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewska, M.; Zielniok, K.; Motyl, T. Autophagy in development and remodelling of mammary gland. In Autophagy—A Double-Edged Sword—Cell Surviv or Death; InTech: Singapore, 2013; Volume 2, p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mailleux, A.A.; Overholtzer, M.; Schmelzle, T.; Bouillet, P.; Strasser, A.; Brugge, J.S. BIM regulates apoptosis during mammary ductal morphogenesis, and its absence reveals alternative cell death mechanisms. Dev. Cell 2007, 12, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuco, A.V.; Ellis, S.E. Comparative aspects of mammary gland development and homeostasis. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2013, 1, 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.F.; Damerell, V.; Omar, R.; Du Toit, M.; Khan, M.; Maranyane, H.M.; Mlaza, M.; Bleloch, J.; Bellis, C.; Sahm, B.D. The roles and regulation of TBX3 in development and disease. Gene 2020, 726, 144223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltmaat, J.M.; Relaix, F.; Le, L.T.; Kratochwil, K.; Sala, F.G.; van Veelen, W.; Rice, R.; Spencer-Dene, B.; Mailleux, A.A.; Rice, D.P.; et al. Gli3-mediated somitic Fgf10 expression gradients are required for the induction and patterning of mammary epithelium along the embryonic axes. Development 2006, 133, 2325–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadigan, K.M.; Waterman, M.L. TCF/LEFs and Wnt signaling in the nucleus. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4, a007906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltmaat, J.M.; Van Veelen, W.; Thiery, J.P.; Bellusci, S. Identification of the mammary line in mouse by Wnt10b expression. Dev. Dyn. 2004, 229, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonadeo, N.; Chimento, A.; Mejía, M.E.; Dallard, B.E.; Sorianello, E.; Becu-Villalobos, D.; Lacau-Mengido, I.; Cristina, C. NOTCH and IGF1 signaling systems are involved in the effects exerted by anthelminthic treatment of heifers on the bovine mammary gland. Vet. Parasitol. 2025, 334, 110390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano, J.V.; Pepper, M.S.; Nakamura, T.; Orci, L.; Montesano, R. Hepatocyte growth factor stimulates extensive development of branching duct-like structures by cloned mammary gland epithelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 1995, 108 Pt 2, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deroo, B.J.; Hewitt, S.C.; Collins, J.B.; Grissom, S.F.; Hamilton, K.J.; Korach, K.S. Profile of estrogen-responsive genes in an estrogen-specific mammary gland outgrowth model. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2009, 76, 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocchinfuso, W.P.; Korach, K.S. Mammary gland development and tumorigenesis in estrogen receptor knockout mice. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 1997, 2, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munarini, N.; Jager, R.; Abderhalden, S.; Zuercher, G.; Rohrbach, V.; Loercher, S.; Pfanner-Meyer, B.; Andres, A.-C.; Ziemiecki, A. Altered mammary epithelial development, pattern formation and involution in transgenic mice expressing the EphB4 receptor tyrosine kinase. J. Cell Sci. 2002, 115, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aupperlee, M.D.; Leipprandt, J.R.; Bennett, J.M.; Schwartz, R.C.; Haslam, S.Z. Amphiregulin mediates progesterone-induced mammary ductal development during puberty. Breast Cancer Res. 2013, 15, R44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauner, G.; Leviav, A.; Mavor, E.; Barash, I. Development of Foreign Mammary Epithelial Morphology in the Stroma of Immunodeficient Mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mallepell, S.; Krust, A.; Chambon, P.; Brisken, C. Paracrine signaling through the epithelial estrogen receptor alpha is required for proliferation and morphogenesis in the mammary gland. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 2196–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonadeo, N.; Becu-Villalobos, D.; Cristina, C.; Lacau-Mengido, I.M. The Notch system during pubertal development of the bovine mammary gland. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, W.; Kleinberg, D.L. Insulin-like growth factor I is essential for terminal end bud formation and ductal morphogenesis during mammary development. Endocrinology 1999, 140, 5075–5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, L.N.; Wadia, P.R.; Schaeberle, C.M.; Rubin, B.S.; Sonnenschein, C.; Soto, A.M. The mammary gland response to estradiol: Monotonic at the cellular level, non-monotonic at the tissue-level of organization? J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006, 101, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Cai, S.; Shin, K.; Lim, A.; Kalisky, T.; Lu, W.J.; Clarke, M.F.; Beachy, P.A. Stromal Gli2 activity coordinates a niche signaling program for mammary epithelial stem cells. Science 2017, 356, eaal3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejrsen, K.; Purup, S.; Vestergaard, M.; Weber, M.S.; Knight, C.H. Growth hormone and mammary development. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 1999, 17, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radcliff, R.P.; VandeHaar, M.J.; Skidmore, A.L.; Chapin, L.T.; Radke, B.R.; Lloyd, J.W.; Stanisiewski, E.P.; Tucker, H.A. Effects of diet and bovine somatotropin on heifer growth and mammary development. J. Dairy Sci. 1997, 80, 1996–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringuet, H.; Petitclerc, D.; Sorensen, M.T.; Gaudreau, P.; Pelletier, G.; Morisset, J.; Couture, Y.; Brazeau, P. Effect of human somatotropin-releasing factor and photoperiods on carcass parameters and mammary gland development of dairy heifers. J. Dairy Sci. 1989, 72, 2928–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, T.; Radosevich, J.A.; Pachori, G.; Mandal, C.C. A Molecular View of Pathological Microcalcification in Breast Cancer. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2016, 21, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shyamala, G.; Yang, X.; Silberstein, G.; Barcellos-Hoff, M.H.; Dale, E. Transgenic mice carrying an imbalance in the native ratio of A to B forms of progesterone receptor exhibit developmental abnormalities in mammary glands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brisken, C.; Park, S.; Vass, T.; Lydon, J.P.; O’Malley, B.W.; Weinberg, R.A. A paracrine role for the epithelial progesterone receptor in mammary gland development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 5076–5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, R.C.; Lydon, J.P.; O’Malley, B.W.; Rosen, J.M. Use of PRKO mice to study the role of progesterone in mammary gland development. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 1997, 2, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodward, T.L.; Beal, W.E.; Akers, R.M. Cell interactions in initiation of mammary epithelial proliferation by oestradiol and progesterone in prepubertal heifers. J. Endocrinol. 1993, 136, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loladze, A.V.; Stull, M.A.; Rowzee, A.M.; Demarco, J.; Lantry, J.H., 3rd; Rosen, C.J.; Leroith, D.; Wagner, K.U.; Hennighausen, L.; Wood, T.L. Epithelial-specific and stage-specific functions of insulin-like growth factor-I during postnatal mammary development. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 5412–5423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turashvili, G.; Bouchal, J.; Burkadze, G.; Kolar, Z. Wnt signaling pathway in mammary gland development and carcinogenesis. Pathobiology 2006, 73, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inman, J.L.; Robertson, C.; Mott, J.D.; Bissell, M.J. Mammary gland development: Cell fate specification, stem cells and the microenvironment. Development 2015, 142, 1028–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, S.L.; Arendt, L.M.; Hernandez, L.L.; Laporta, J. Characterizing serotonin expression throughout bovine mammary gland developmental stages and its relationship with 17β-estradiol at puberty. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0319914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, W.T.; Jeong, H.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Song, H. Effects of the Insulin-like Growth Factor Pathway on the Regulation of Mammary Gland Development. Dev. Reprod. 2016, 20, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaji, D.; Kang, K.; Robinson, G.W.; Hennighausen, L. Sequential activation of genetic programs in mouse mammary epithelium during pregnancy depends on STAT5A/B concentration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 1622–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, E.C.; Brown, S.O.; Germain, D. The Multi-Faced Role of PAPP-A in Post-Partum Breast Cancer: IGF-Signaling is Only the Beginning. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2020, 25, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternlicht, M.D.; Sunnarborg, S.W.; Kouros-Mehr, H.; Yu, Y.; Lee, D.C.; Werb, Z. Mammary ductal morphogenesis requires paracrine activation of stromal EGFR via ADAM17-dependent shedding of epithelial amphiregulin. Development 2005, 132, 3923–3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Yu, M.; Zhou, C.; Qi, H.; Wen, X.; Hou, X.; Li, M.; Gao, X. FABP5 is a critical regulator of methionine- and estrogen-induced SREBP-1c gene expression in bovine mammary epithelial cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 234, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchi, I.; Mento, E.; Kuznetsov, V.A.; Scotti, M.; Valsecchi, V.; Simionati, B.; Vicinanza, E.; Valle, G.; Pilotti, S.; Reinbold, R.; et al. Gene expression profiles of epithelial cells microscopically isolated from a breast-invasive ductal carcinoma and a nodal metastasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 18147–18152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fata, J.E.; Werb, Z.; Bissell, M.J. Regulation of mammary gland branching morphogenesis by the extracellular matrix and its remodeling enzymes. Breast Cancer Res. 2004, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiseman, B.S.; Sternlicht, M.D.; Lund, L.R.; Alexander, C.M.; Mott, J.; Bissell, M.J.; Soloway, P.; Itohara, S.; Werb, Z. Site-specific inductive and inhibitory activities of MMP-2 and MMP-3 orchestrate mammary gland branching morphogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 162, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochter, A.; Galosy, S.; Muschler, J.; Freedman, N.; Werb, Z.; Bissell, M.J. Matrix metalloproteinase stromelysin-1 triggers a cascade of molecular alterations that leads to stable epithelial-to-mesenchymal conversion and a premalignant phenotype in mammary epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 1997, 139, 1861–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, H.; Lo, A.T.; Inman, J.L.; Alcaraz, J.; Ghajar, C.M.; Mott, J.D.; Nelson, C.M.; Chen, C.S.; Zhang, H.; Bascom, J.L.; et al. Transmembrane/cytoplasmic, rather than catalytic, domains of Mmp14 signal to MAPK activation and mammary branching morphogenesis via binding to integrin β1. Development 2013, 140, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schams, D.; Kohlenberg, S.; Amselgruber, W.; Berisha, B.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Sinowatz, F. Expression and localisation of oestrogen and progesterone receptors in the bovine mammary gland during development, function and involution. J. Endocrinol. 2003, 177, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henricks, D.M.; Dickey, J.F.; Hill, J.R.; Johnston, W.E. Plasma estrogen and progesterone levels after mating, and during late pregnancy and postpartum in cows. Endocrinology 1972, 90, 1336–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, H.N.; Graham, J.D.; Clarke, C.L. Minireview: Progesterone Regulation of Proliferation in the Normal Human Breast and in Breast Cancer: A Tale of Two Scenarios? Mol. Endocrinol. 2015, 29, 1230–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, S.R.; Hilton, H.N.; Ormandy, C.J. The alveolar switch: Coordinating the proliferative cues and cell fate decisions that drive the formation of lobuloalveoli from ductal epithelium. Breast Cancer Res. 2006, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkington, R.W.; Hill, R.L. Lactose synthetase: Progesterone inhibition of the induction of alpha-lactalbumin. Science 1969, 163, 1458–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, J.M.; O’Neal, D.L.; McHugh, J.E.; Comstock, J.P. Progesterone-mediated inhibition of casein mRNA and polysomal casein synthesis in the rat mammary gland during pregnancy. Biochemistry 1978, 17, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Yang, M.; Xiang, Z. Serum prolactin levels across pregnancy and the establishment of reference intervals. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2018, 56, 838–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisken, C.; Kaur, S.; Chavarria, T.E.; Binart, N.; Sutherland, R.L.; Weinberg, R.A.; Kelly, P.A.; Ormandy, C.J. Prolactin controls mammary gland development via direct and indirect mechanisms. Dev. Biol. 1999, 210, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormandy, C.J.; Naylor, M.; Harris, J.; Robertson, F.; Horseman, N.D.; Lindeman, G.J.; Visvader, J.; Kelly, P.A. Investigation of the transcriptional changes underlying functional defects in the mammary glands of prolactin receptor knockout mice. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 2003, 58, 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, W.W.; Hartmann, P.E. Initiation of human lactation: Secretory differentiation and secretory activation. J. Mammary Gland. Biol. Neoplasia 2007, 12, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, V.; Young, J.; Binart, N. Prolactin—A pleiotropic factor in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodside, B. Prolactin and the hyperphagia of lactation. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 91, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augustine, R.A.; Ladyman, S.R.; Bouwer, G.T.; Alyousif, Y.; Sapsford, T.J.; Scott, V.; Kokay, I.C.; Grattan, D.R.; Brown, C.H. Prolactin regulation of oxytocin neurone activity in pregnancy and lactation. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 3591–3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terzi, D.; Gaspari, S.; Manouras, L.; Descalzi, G.; Mitsi, V.; Zachariou, V. RGS9-2 modulates sensory and mood related symptoms of neuropathic pain. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2014, 115, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.M.; Imami, N.; Johnson, M.R. Progesterone modulation of pregnancy-related immune responses. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horigan, K.C.; Trott, J.F.; Barndollar, A.S.; Scudder, J.M.; Blauwiekel, R.M.; Hovey, R.C. Hormone interactions confer specific proliferative and histomorphogenic responses in the porcine mammary gland. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2009, 37, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volker, S.E.; Hedrick, S.E.; Feeney, Y.B.; Clevenger, C.V. Cyclophilin A Function in Mammary Epithelium Impacts Jak2/Stat5 Signaling, Morphogenesis, Differentiation, and Tumorigenesis in the Mammary Gland. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 3877–3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.C.; Zhao, S.G.; Wang, S.S.; Luo, C.C.; Gao, H.N.; Zheng, N.; Wang, J.Q. d-Glucose and amino acid deficiency inhibits casein synthesis through JAK2/STAT5 and AMPK/mTOR signaling pathways in mammary epithelial cells of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 1737–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palin, M.; Beaudry, D.; Roberge, C.; Farmer, C. Expression levels of STAT5A and STAT5B in mammary parenchymal tissue from Upton-Meishan and Large White gilts. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2002, 82, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rädler, P.D.; Wehde, B.L.; Wagner, K.U. Crosstalk between STAT5 activation and PI3K/AKT functions in normal and transformed mammary epithelial cells. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2017, 451, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, X.; Sun, D.; Han, Q.; Yi, L.; Wu, Y.; Liu, X. Hypoxia induces pulmonary arterial fibroblast proliferation, migration, differentiation and vascular remodeling via the PI3K/Akt/p70S6K signaling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 41, 2461–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, F.; Fu, Q.; Zhu, X.; Shu, G.; Wang, L.; Gao, P.; Xi, Q.; et al. Stearic acid suppresses mammary gland development by inhibiting PI3K/Akt signaling pathway through GPR120 in pubertal mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 491, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, W.; White, R.; Liu, J.; Liu, H. Organelles coordinate milk production and secretion during lactation: Insights into mammary pathologies. Prog. Lipid Res. 2022, 86, 101159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, C.J. Alveolar cells in the mammary gland: Lineage commitment and cell death. Biochem. J. 2022, 479, 995–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Li, Q.; Huang, T. Microarray analysis of gene expression profiles in the bovine mammary gland during lactation. Sci. China Life Sci. 2010, 53, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, M.C.; McManaman, J.L.; Hunter, L.; Phang, T.; Neville, M.C. Functional development of the mammary gland: Use of expression profiling and trajectory clustering to reveal changes in gene expression during pregnancy, lactation, and involution. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2003, 8, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, M.C.; McManaman, J.L.; Phang, T.; Russell, T.; Kominsky, D.J.; Serkova, N.J.; Stein, T.; Anderson, S.M.; Neville, M.C. Metabolic regulation in the lactating mammary gland: A lipid synthesizing machine. Physiol. Genom. 2007, 28, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.N.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.O.; Li, Y.C.; Tian, F.; Jiang, M.F. Characterisation of gene expression related to milk fat synthesis in the mammary tissue of lactating yaks. J. Dairy Res. 2017, 84, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Zhu, J.; Luo, J.; Cao, W.; Shi, H.; Yao, D.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Xu, H.; Yu, K. Genes regulating lipid and protein metabolism are highly expressed in mammary gland of lactating dairy goats. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2015, 15, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Påhlman, S.; Lund, L.R.; Jögi, A. Differential HIF-1α and HIF-2α Expression in Mammary Epithelial Cells during Fat Pad Invasion, Lactation, and Involution. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, M.K.; Janjanam, J.; Naru, J.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, S.; Singh, S.; Mohapatra, S.K.; Kola, S.; Anand, V.; Jaswal, S.; et al. DIGE based proteome analysis of mammary gland tissue in water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis): Lactating vis-a-vis heifer. J. Proteom. 2015, 119, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finucane, K.A.; McFadden, T.B.; Bond, J.P.; Kennelly, J.J.; Zhao, F.Q. Onset of lactation in the bovine mammary gland: Gene expression profiling indicates a strong inhibition of gene expression in cell proliferation. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2008, 8, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, M.; Etchebarne, B.; Bong, J.; VandeHaar, M. Gene expression profiling of liver and mammary tissues of lactating dairy cows. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 22, 871–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, J.; Davis, T.J. Physiology, Lactation; StatPearls Publishing LLC: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, C.H. Lactation and gestation in dairy cows: Flexibility avoids nutritional extremes. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2001, 60, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadbakht, Z.; Fanaei, H.; Karajibani, M.; Montazerifar, F. Effect of type 1 diabetes during pregnancy and lactation on neonatal hypoxia-ischemia injury and apoptotic gene expression. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2023, 83, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eknæs, M.; Chilliard, Y.; Hove, K.; Inglingstad, R.A.; Bernard, L.; Volden, H. Feeding of palm oil fatty acids or rapeseed oil throughout lactation: Effects on energy status, body composition, and milk production in Norwegian dairy goats. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 7588–7601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, R.J.; Annen-Dawson, E.L.; Pezeshki, A. Effects of continuous lactation and short dry periods on mammary function and animal health. Animal 2012, 6, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.K. Advancements in management practices from far-off dry period to initial lactation period for improved production, reproduction, and health performances in dairy animals: A review. Int. J. Livest. Res. 2021, 11, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.J. Involution: Apoptosis and tissue remodelling that convert the mammary gland from milk factory to a quiescent organ. Breast Cancer Res. 2006, 8, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Vetharaniam, I.; Dobson, J.M.; Prewitz, M.; Oden, K.; Murney, R.; Swanson, K.M.; McDonald, R.; Henderson, H.V.; Stelwagen, K. Cell survival signaling in the bovine mammary gland during the transition from lactation to involution. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 7523–7543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, T.J.; Lloyd-Lewis, B.; Resemann, H.K.; Ramos-Montoya, A.; Skepper, J.; Watson, C.J. Stat3 controls cell death during mammary gland involution by regulating uptake of milk fat globules and lysosomal membrane permeabilization. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.R.; Tarullo, S.E.; Crump, L.S.; Lyons, T.R. Studies of postpartum mammary gland involution reveal novel pro-metastatic mechanisms. J. Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2019, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonner, E.; Allan, G.; Shkreta, L.; Webster, J.; Whitelaw, C.B.; Flint, D.J. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-5 (IGFBP-5) potentially regulates programmed cell death and plasminogen activation in the mammary gland. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2000, 480, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuco, A.V.; Akers, R.M. Mammary involution in dairy animals. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 1999, 4, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamay, A.; Shapiro, F.; Mabjeesh, S.J.; Silanikove, N. Casein-derived phosphopeptides disrupt tight junction integrity, and precipitously dry up milk secretion in goats. Life Sci. 2002, 70, 2707–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, L.R.; Rømer, J.; Thomasset, N.; Solberg, H.; Pyke, C.; Bissell, M.J.; Danø, K.; Werb, Z. Two distinct phases of apoptosis in mammary gland involution: Proteinase-independent and -dependent pathways. Development 1996, 122, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, K.D.; Lindeman, G.J.; Visvader, J.E. The molecular culprits underlying precocious mammary gland involution. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2007, 12, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, G.; Merin, U.; Lavi, Y.; Egber, A.; Silanikove, N. Aetiology of intramammary infection and its effect on milk composition in goat flocks. J. Dairy Res. 2007, 74, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierie, B.; Gorska, A.E.; Stover, D.G.; Moses, H.L. TGF-beta promotes cell death and suppresses lactation during the second stage of mammary involution. J. Cell Physiol. 2009, 219, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, V.; Jaswal, S.; Singh, S.; Kumar, S.; Jena, M.K.; Verma, A.K.; Yadav, M.L.; Janjanam, J.; Lotfan, M.; Malakar, D.; et al. Functional characterization of Mammary Gland Protein-40, a chitinase-like glycoprotein expressed during mammary gland apoptosis. Apoptosis 2016, 21, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monks, J.; Rosner, D.; Geske, F.J.; Lehman, L.; Hanson, L.; Neville, M.C.; Fadok, V.A. Epithelial cells as phagocytes: Apoptotic epithelial cells are engulfed by mammary alveolar epithelial cells and repress inflammatory mediator release. Cell Death Differ. 2005, 12, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erb, R.E.; Monk, E.L.; Mollett, T.A.; Malven, P.V.; Callahan, C.J. Estrogen, progesterone, prolactin and other changes associated with bovine lactation induced with estradiol-17beta and progesterone. J. Anim. Sci. 1976, 42, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Bazer, F.W.; Johnson, G.A.; Knabe, D.A.; Burghardt, R.C.; Spencer, T.E.; Li, X.L.; Wang, J.J. Triennial Growth Symposium: Important roles for L-glutamine in swine nutrition and production. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 89, 2017–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Liu, X.; Robinson, G.; Bar-Peled, U.; Wagner, K.U.; Young, W.S.; Hennighausen, L.; Furth, P.A. Mammary-derived signals activate programmed cell death during the first stage of mammary gland involution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 3425–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Melenhorst, J.J.; Hennighausen, L. Loss of interleukin 6 results in delayed mammary gland involution: A possible role for mitogen-activated protein kinase and not signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. Mol. Endocrinol. 2002, 16, 2902–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Betts, C.; Pennock, N.; Mitchell, E.; Schedin, P. Mammary Gland Involution Provides a Unique Model to Study the TGF-β Cancer Paradox. J. Clin. Med. 2017, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, L.D.; Dover, H.; Casey, T.; VandeHaar, M.J.; Plaut, K. Characterization of mammary stromal remodeling during the dry period. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 2433–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Bubolz, J.W.; do Amaral, B.C.; Thompson, I.M.; Hayen, M.J.; Johnson, S.E.; Dahl, G.E. Effect of heat stress during the dry period on mammary gland development. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 5976–5986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skibiel, A.L.; Koh, J.; Zhu, N.; Zhu, F.; Yoo, M.J.; Laporta, J. Carry-over effects of dry period heat stress on the mammary gland proteome and phosphoproteome in the subsequent lactation of dairy cows. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, W.L. Mammary gland function during involution. J. Dairy Sci. 1989, 72, 1637–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlgemuth, S.E.; Ramirez-Lee, Y.; Tao, S.; Monteiro, A.P.A.; Ahmed, B.M.; Dahl, G.E. Short communication: Effect of heat stress on markers of autophagy in the mammary gland during the dry period. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 4875–4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.P.A.; Guo, J.R.; Weng, X.S.; Ahmed, B.M.; Hayen, M.J.; Dahl, G.E.; Bernard, J.K.; Tao, S. Effect of maternal heat stress during the dry period on growth and metabolism of calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 3896–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, G.E.; Tao, S.; Thompson, I.M. Lactation Biology Symposium: Effects of photoperiod on mammary gland development and lactation. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Duan, X.; Zhang, L.; Guo, Y.; Cao, J.; Ao, W.; Xuan, R. Transcriptomic analysis of mammary gland tissues in lactating and non-lactating dairy goats reveals miRNA-mediated regulation of lactation, involution, and remodeling. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1604855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melet, A.; Khosravi-Far, R. Physiologic and Pathological Cell Death in the Mammary Gland. In Apoptosis: Physiology and Pathology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 250–272. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, R.W.; Wayland, M.T.; Lee, J.; Freeman, T.; Watson, C.J. Gene expression profiling of mammary gland development reveals putative roles for death receptors and immune mediators in post-lactational regression. Breast Cancer Res. 2004, 6, R92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, T.; Morris, J.S.; Davies, C.R.; Weber-Hall, S.J.; Duffy, M.A.; Heath, V.J.; Bell, A.K.; Ferrier, R.K.; Sandilands, G.P.; Gusterson, B.A. Involution of the mouse mammary gland is associated with an immune cascade and an acute-phase response, involving LBP, CD14 and STAT3. Breast Cancer Res. 2004, 6, R75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annen, E.; Collier, R.; McGuire, M.; Vicini, J. Effects of dry period length on milk yield and mammary epithelial cells. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, E66–E76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akers, R.M. A 100-Year Review: Mammary development and lactation. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 10332–10352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.; Losand, B.; Tuchscherer, A.; Rehbock, F.; Blum, E.; Yang, W.; Bruckmaier, R.M.; Sanftleben, P.; Hammon, H.M. Effects of dry period length on milk production, body condition, metabolites, and hepatic glucose metabolism in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 1772–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, A.J.; Purcell, P.J.; Wylie, A.R.; Gordon, A.W.; Ferris, C.P. Effects of dry period length and concentrate protein content in late lactation on body condition score change and subsequent lactation performance of thin high genetic merit dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 1795–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohakare, J.; Südekum, K.; Pattanaik, A. Nutrition-induced changes of growth from birth to first calving and its impact on mammary development and first-lactation milk yield in dairy heifers: A review. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 25, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejrsen, K. Relationships between nutrition, puberty and mammary development in cattle. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1994, 53, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejrsen, K.; Huber, J.; Tucker, H.; Akers, R. Influence of nutrition on mammary development in pre-and postpubertal heifers. J. Dairy Sci. 1982, 65, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soberon, F.; Van Amburgh, M. Effects of preweaning nutrient intake in the developing mammary parenchymal tissue. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 4996–5004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vailati-Riboni, M.; Bucktrout, R.; Zhan, S.; Geiger, A.; McCann, J.; Akers, R.M.; Loor, J. Higher plane of nutrition pre-weaning enhances Holstein calf mammary gland development through alterations in the parenchyma and fat pad transcriptome. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, M.; Capuco, A.; Ross, D.; Lintault, L.; Van Amburgh, M. Developmental and nutritional regulation of the prepubertal heifer mammary gland: I. Parenchyma and fat pad mass and composition. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 4289–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Periods of Possible Impact | Signaling Pathway | Gene/Transcription Factor | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embryonic, pubertal, and pregnancy stages | Wnt | Wnt3, Wnt6, Wnt10b, Wnt4, LEF1, LEF, β-catenin | [58,59] |

| Embryonic, pubertal, and pregnancy stages | BMP | BMP2, BMP4 | [60,61] |

| Embryonic, pubertal, and pregnancy stages | PTHLH | PTHrP, PTH1R | [56] |

| Embryonic, pubertal, and pregnancy stages | Hedgehog | SHH, PTCH1, GLI3 | [62,63] |

| Embryonic, pubertal, and pregnancy stages | FGF | FGF10, FGFR2b | [53,64] |

| Embryonic, pubertal, and pregnancy stages | Notch | NOTCH2, NOTCH4 | [65] |

| Pregnancy, lactation, and involution stages | JAK-STAT | STAT5a, STAT5b, STAT6, STAT3, LIF | [4,65] |

| Pregnancy, lactation, and involution stages | RANKL-RANK | RANKL | [66] |

| Embryonic, pubertal, pregnancy, lactation, and involution stages | PI3K-Akt | PI3K, Akt1, mTOR, PIP2, PIP3, PTEN, Cyclin D1 | [67] |

| Pubertal, pregnancy, lactation, and involution stages | NF-κB | NF-κB, IKK, RelA, p65, p50 | [68,69] |

| Embryonic, pubertal, pregnancy, and involution stages | TGF-β | TGF-β1, TGF-βR, SMAD2, SMAD3, SMAD4 | [69] |

| Pubertal, pregnancy, and lactation stages | MAPK | RAS, RAF, MEK, ERK | [70,71] |

| Pubertal, pregnancy, lactation, and involution stages | Autophagy | ATG5, Beclin1, LC3 | [72] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, X.; Ullah, A.; Shi, L.; Dou, M.; Wang, C.; Khan, M.Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X. Molecular Regulatory Mechanisms of Mammary Gland Development: A Review. Animals 2025, 15, 3480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233480

Zhou X, Ullah A, Shi L, Dou M, Wang C, Khan MZ, Wang C, Zhang X. Molecular Regulatory Mechanisms of Mammary Gland Development: A Review. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233480

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Xiangnan, Abd Ullah, Limeng Shi, Manna Dou, Changfa Wang, Muhammad Zahoor Khan, Chunming Wang, and Xinhao Zhang. 2025. "Molecular Regulatory Mechanisms of Mammary Gland Development: A Review" Animals 15, no. 23: 3480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233480

APA StyleZhou, X., Ullah, A., Shi, L., Dou, M., Wang, C., Khan, M. Z., Wang, C., & Zhang, X. (2025). Molecular Regulatory Mechanisms of Mammary Gland Development: A Review. Animals, 15(23), 3480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233480