Bovine Adipocyte-Derived Exosomes Transport LncRNAs to Regulate Adipogenic Transdifferentiation of Bovine Muscle Satellite Cells

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

Sample Collection

2.2. Isolation, Culture, and Differentiation of Bovine Preadipocytes

2.3. Isolation, Culture, and Differentiation of Bovine MSCs

2.4. Oil Red O Staining and Determination of Triglyceride Content

2.5. Immunofluorescence

2.6. Total RNA Extraction and Real-Time Fluorescence Quantitative PCR

2.7. Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analysis

2.8. Co-Culture System Establishment

2.9. Adipocyte-Derived Exosomes Extraction, Characterization and Co-Culture with MSCs

2.10. Exosomal LncRNA-Seq

2.11. Cell Transfection

2.12. Dual-Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay

2.13. Data Statistics and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Morphology, Differentiation, and Identification of Bovine Precursor Adipocytes

3.2. Morphology, Differentiation, and Identification of Bovine MSCs

3.3. Lipogenic Transdifferentiation of MSCs in Co-Culture System

3.4. Identification and Role of Bovine Adipocyte-Derived Exosomes

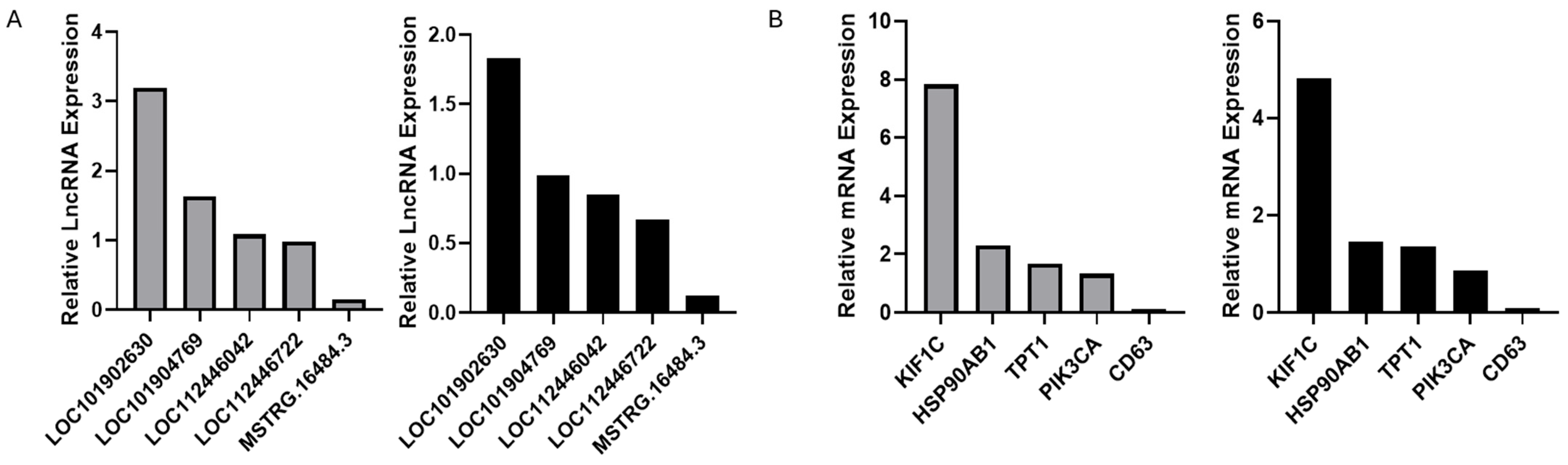

3.5. LncRNA-Seq of Adipocyte-Derived Exosomes

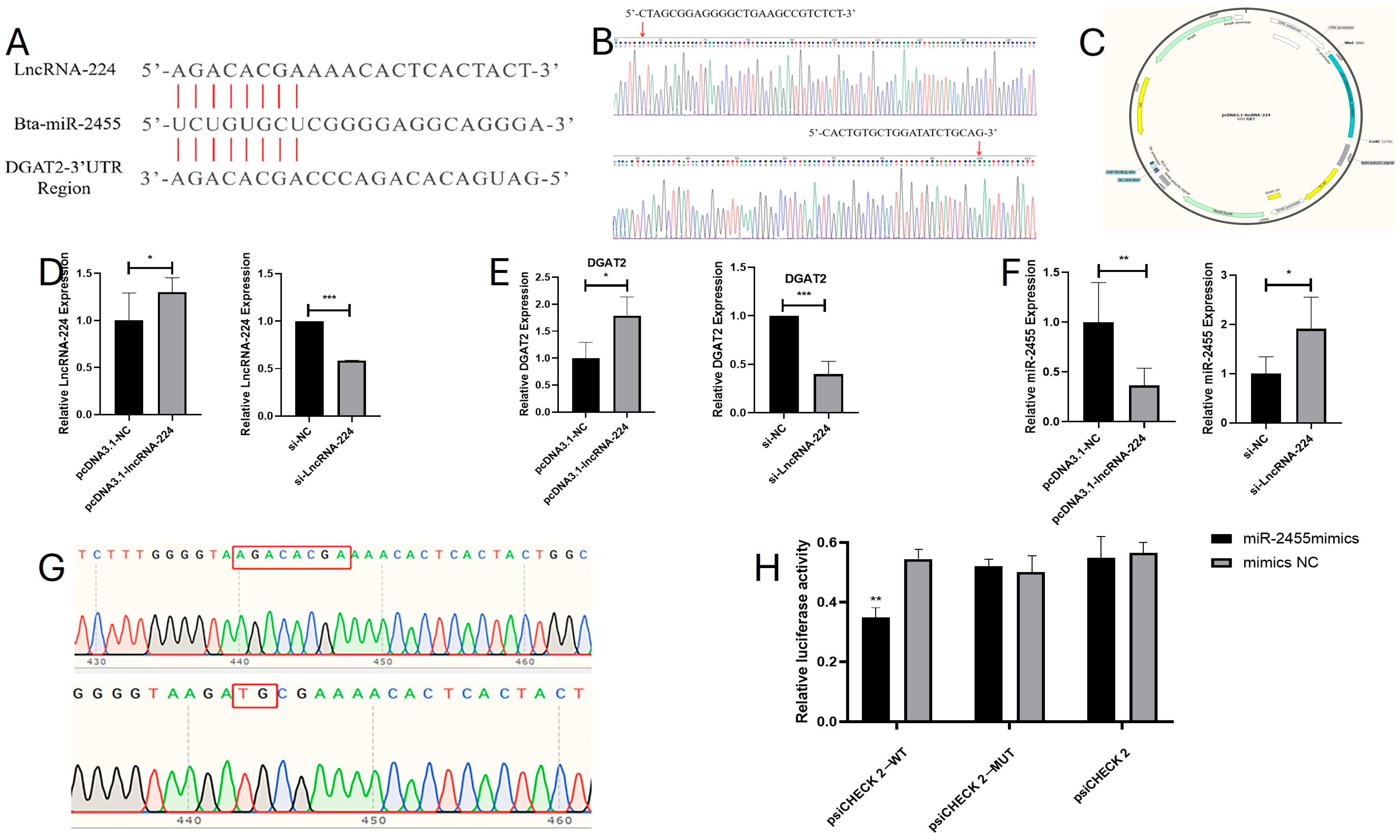

3.6. Bioinformatics Analysis and Functional Validation of lncDGAT2

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Khan, R.; Raza, S.H.A.; Junjvlieke, Z.; Xiaoyu, W.; Garcia, M.; Elnour, I.E.; Hongbao, W.; Linsen, Z. Function and Transcriptional Regulation of Bovine TORC2 Gene in Adipocytes: Roles of C/EBPγ, XBP1, INSM1 and ZNF263. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Mei, C.; Raza, S.H.A.; Khan, R.; Cheng, G.; Zan, L. SIRT5 Inhibits Bovine Preadipocyte Differentiation and Lipid Deposition by Activating AMPK and Repressing MAPK Signal Pathways. Genomics 2020, 112, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shijun, L.; Khan, R.; Raza, S.H.A.; Jieyun, H.; Chugang, M.; Kaster, N.; Gong, C.; Chunping, Z.; Schreurs, N.M.; Linsen, Z. Function and Characterization of the Promoter Region of Perilipin 1 (PLIN1): Roles of E2F1, PLAG1, C/EBPβ, and SMAD3 in Bovine Adipocytes. Genomics 2020, 112, 2400–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamrick, M.W.; McGee-Lawrence, M.E.; Frechette, D.M. Fatty Infiltration of Skeletal Muscle: Mechanisms and Comparisons with Bone Marrow Adiposity. Front. Endocrinol. 2016, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.D.; Enser, M.; Fisher, A.V.; Nute, G.R.; Sheard, P.R.; Richardson, R.I.; Hughes, S.I.; Whittington, F.M. Fat Deposition, Fatty Acid Composition and Meat Quality: A Review. Meat Sci. 2008, 78, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, A.; Pearson, A.M. Influence of Ante- and Postmortem Treatments Upon Muscle Composition and Meat Quality. Adv. Food Res. 1980, 26, 53–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer, T.N. Relationship of Marbling to the Palatability of Beef. J. Anim. Sci. 1963, 22, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, R.; Gómez, M.; Fonseca, S.; Lorenzo, J.M. Effect of Different Cooking Methods on Lipid Oxidation and Formation of Volatile Compounds in Foal Meat. Meat Sci. 2014, 97, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.T.; Hochfeld, W.E.; Myburgh, R.; Pepper, M.S. Adipocyte and Adipogenesis. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 92, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uezumi, A.; Fukada, S.; Yamamoto, N.; Takeda, S.; Tsuchida, K. Mesenchymal Progenitors Distinct from Satellite Cells Contribute to Ectopic Fat Cell Formation in Skeletal Muscle. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yada, E.; Yamanouchi, K.; Nishihara, M. Adipogenic Potential of Satellite Cells from Distinct Skeletal Muscle Origins in the Rat. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2006, 68, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, A.; Komaki, M.; Rudnicki, M. Muscle Satellite Cells Are Multipotential Stem Cells That Exhibit Myogenic, Osteogenic, and Adipogenic Differentiation. Differ. Res. Biol. Divers. 2001, 68, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Sun, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, E.; Jin, H.; Hua, H.; Jin, Q.; Li, X. Study on the Effect of Oleic Acid-Induced Lipogenic Differentiation of Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cells in Yanbian Cattle and Related Mechanisms. Animals 2023, 13, 3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, X.; Gao, G.; Du, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Yang, F.; Zhou, X.; Long, D.; Huang, J.; Liu, Z.; et al. Time-Series Clustering of lncRNA-mRNA Expression during the Adipogenic Transdifferentiation of Porcine Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cells. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 2038–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Xue, K.; Wang, Y.; Niu, L.; Li, L.; Zhong, T.; Guo, J.; Feng, J.; Song, T.; Zhang, H. Molecular and Functional Characterization of the Adiponectin (AdipoQ) Gene in Goat Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cells. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 31, 1088–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Chung, K.Y.; Johnson, B.J.; Go, G.W.; Kim, K.H.; Choi, C.W.; Smith, S.B. Co-Culture of Bovine Muscle Satellite Cells with Preadipocytes Increases PPARγ and C/EBPβ Gene Expression in Differentiated Myoblasts and Increases GPR43 Gene Expression in Adipocytes. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013, 24, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Cui, H.; Zhao, G.; Liu, R.; Li, Q.; Zheng, M.; Guo, Y.; Wen, J. Intramuscular Preadipocytes Impede Differentiation and Promote Lipid Deposition of Muscle Satellite Cells in Chickens. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krylova, S.V.; Feng, D. The Machinery of Exosomes: Biogenesis, Release, and Uptake. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, R.J.; Jensen, S.S.; Lim, J.W.E. Proteomic Profiling of Exosomes: Current Perspectives. Proteomics 2008, 8, 4083–4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, N.; Yan, T.; Shi, Y.-N.; Chen, J.; Zhang, C.-J.; Xie, X.-J.; Liao, D.-F.; Qin, L. The Crosstalk: Exosomes and Lipid Metabolism. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, W.; Riopel, M.; Bandyopadhyay, G.; Dong, Y.; Birmingham, A.; Seo, J.B.; Ofrecio, J.M.; Wollam, J.; Hernandez-Carretero, A.; Fu, W.; et al. Adipose Tissue Macrophage-Derived Exosomal miRNAs Can Modulate In Vivo and In Vitro Insulin Sensitivity. Cell 2017, 171, 372–384.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Du, H.; Wei, S.; Feng, L.; Li, J.; Yao, F.; Zhang, M.; Hatch, G.M.; Chen, L. Adipocyte-Derived Exosomal MiR-27a Induces Insulin Resistance in Skeletal Muscle Through Repression of PPARγ. Theranostics 2018, 8, 2171–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Ru, Z.; Xiao, W.; Xiong, Z.; Wang, C.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H. Adipose Tissue Browning in Cancer-Associated Cachexia Can Be Attenuated by Inhibition of Exosome Generation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 506, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, G.; Sah, R.P.; Javeed, N.; Dutta, S.K.; Smyrk, T.C.; Lau, J.S.; Giorgadze, N.; Tchkonia, T.; Kirkland, J.L.; Chari, S.T.; et al. Pathogenesis of Pancreatic Cancer Exosome-Induced Lipolysis in Adipose Tissue. Gut 2016, 65, 1165–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Li, X.; Xu, M.; Wang, J.; Zhao, R.C. Reduced Adipogenesis after Lung Tumor Exosomes Priming in Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells via TGFβ Signaling Pathway. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 435, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaherty, S.E.; Grijalva, A.; Xu, X.; Ables, E.; Nomani, A.; Ferrante, A.W. A Lipase-Independent Pathway of Lipid Release and Immune Modulation by Adipocytes. Science 2019, 363, 989–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, N.A.; González-King, H.; Grueso, E.; Sánchez, R.; Martinez-Romero, A.; Jávega, B.; O’Connor, J.E.; Simons, P.J.; Handberg, A.; Sepúlveda, P. Circulating Exosomes Deliver Free Fatty Acids from the Bloodstream to Cardiac Cells: Possible Role of CD36. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Record, M.; Carayon, K.; Poirot, M.; Silvente-Poirot, S. Exosomes as New Vesicular Lipid Transporters Involved in Cell-Cell Communication and Various Pathophysiologies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1841, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranendonk, M.E.G.; Visseren, F.L.J.; van Herwaarden, J.A.; Nolte-’t Hoen, E.N.M.; de Jager, W.; Wauben, M.H.M.; Kalkhoven, E. Effect of Extracellular Vesicles of Human Adipose Tissue on Insulin Signaling in Liver and Muscle Cells. Obesity 2014, 22, 2216–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obata, Y.; Kita, S.; Koyama, Y.; Fukuda, S.; Takeda, H.; Takahashi, M.; Fujishima, Y.; Nagao, H.; Masuda, S.; Tanaka, Y.; et al. Adiponectin/T-Cadherin System Enhances Exosome Biogenesis and Decreases Cellular Ceramides by Exosomal Release. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e99680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattick, J.S.; Amaral, P.P.; Carninci, P.; Carpenter, S.; Chang, H.Y.; Chen, L.-L.; Chen, R.; Dean, C.; Dinger, M.E.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; et al. Long Non-Coding RNAs: Definitions, Functions, Challenges and Recommendations. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Xie, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Y. The Role of Long Noncoding RNAs in Livestock Adipose Tissue Deposition—A Review. Anim. Biosci. 2021, 34, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, X.; Qin, J.; Liu, S.; Zhao, R.; Yu, T.; Chu, G.; Yang, G.; Pang, W. Comparative Analysis of Long Noncoding RNAs Expressed during Intramuscular Adipocytes Adipogenesis in Fat-Type and Lean-Type Pigs. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 12122–12130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Lu, S.; Yin, L.; Zong, C.; Cui, S.; Qin, D.; Yang, Y.; Guan, Q.; Li, X.; et al. The Role and Possible Mechanism of lncRNA U90926 in Modulating 3T3-L1 Preadipocyte Differentiation. Int. J. Obes. 2017, 41, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Yu, D.; Nian, X.; Liu, J.; Koenig, R.J.; Xu, B.; Sheng, L. LncRNA SRA Promotes Hepatic Steatosis through Repressing the Expression of Adipose Triglyceride Lipase (ATGL). Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Cheng, M.; Niu, Y.; Chi, X.; Liu, X.; Fan, J.; Fan, H.; Chang, Y.; Yang, W. Identification of a Novel Human Long Non-Coding RNA That Regulates Hepatic Lipid Metabolism by Inhibiting SREBP-1c. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 13, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Bi, Y.; Zhao, J.; Gao, C.; Si, X.; Dai, H.; Asmamaw, M.D.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, W.; et al. The Role of lncRNAs and Exosomal lncRNAs in Cancer Metastasis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Tian, W.; Wang, D.; Yang, L.; Wang, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhi, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; et al. LncHLEF Promotes Hepatic Lipid Synthesis through miR-2188-3p/GATA6 Axis and Encoding Peptides and Enhances Intramuscular Fat Deposition via Exosome. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G. Screening of Candidate Genes Associated to Meat Qualitytraits of Yanbian Yellow Cattle by a Combination of miRNA and Functional Genes Transcriptome. Ph.D. Thesis, Yanbian University, Yanji, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, S.M.; Gardner, G.E.; McGilchrist, P.; Pethick, D.W.; Polkinghorne, R.; Thompson, J.M.; Tarr, G. Prediction of Consumer Palatability in Beef Using Visual Marbling Scores and Chemical Intramuscular Fat Percentage. Meat Sci. 2021, 181, 108322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciorati, C.; Clementi, E.; Manfredi, A.A.; Rovere-Querini, P. Fat Deposition and Accumulation in the Damaged and Inflamed Skeletal Muscle: Cellular and Molecular Players. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 2135–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trayhurn, P.; Drevon, C.A.; Eckel, J. Secreted Proteins from Adipose Tissue and Skeletal Muscle—Adipokines, Myokines and Adipose/Muscle Cross-Talk. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2011, 117, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietze, D.; Koenen, M.; Röhrig, K.; Horikoshi, H.; Hauner, H.; Eckel, J. Impairment of Insulin Signaling in Human Skeletal Muscle Cells by Co-Culture with Human Adipocytes. Diabetes 2002, 51, 2369–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhao, R.; Ma, W.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, G. Comparison of Lipid Deposition of Intramuscular Preadipocytes in Tan Sheep Co-Cultured with Satellite Cells or Alone. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 106, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, Y.; Wang, G.; Diao, Y.; Long, Y.; Fu, X.; Weng, M.; Zhou, L.; Sun, K.; Cheung, T.H.; Ip, N.Y.; et al. A Molecular Switch Regulating Cell Fate Choice between Muscle Progenitor Cells and Brown Adipocytes. Dev. Cell 2017, 41, 382–391.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, X.; Peng, X.; Wei, H.; Peng, J.; Jiang, S. Activation of PPARγ2 by PPARγ1 through a Functional PPRE in Transdifferentiation of Myoblasts to Adipocytes Induced by EPA. Cell Cycle 2015, 14, 1830–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Liu, W.; Nie, Y.; Qaher, M.; Horton, H.E.; Yue, F.; Asakura, A.; Kuang, S. Loss of MyoD Promotes Fate Transdifferentiation of Myoblasts Into Brown Adipocytes. eBioMedicine 2017, 16, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, S.; Saieva, L.; Taverna, S.; Alessandro, R. Contribution of Proteomics to Understanding the Role of Tumor-Derived Exosomes in Cancer Progression: State of the Art and New Perspectives. Proteomics 2013, 13, 1581–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojima, K.; Muroya, S.; Wada, H.; Ogawa, K.; Oe, M.; Takimoto, K.; Nishimura, T. Immature Adipocyte-Derived Exosomes Inhibit Expression of Muscle Differentiation Markers. FEBS Open Bio 2021, 11, 768–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théry, C.; Amigorena, S.; Raposo, G.; Clayton, A. Isolation and Characterization of Exosomes from Cell Culture Supernatants and Biological Fluids. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. 2006, 30, 3.22.1–3.22.29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, G.; Ahmed, W. Isolation and Characterization of Exosomes Released by EBV-Immortalized Cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1532, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, A.V.; Bell, J.; Barter, P. The Integration of Lipid-Sensing and Anti-Inflammatory Effects: How the PPARs Play a Role in Metabolic Balance. Nucl. Recept. 2007, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, J.; Mulet, C.; Saffarian, A.; Cavin, J.-B.; Ducroc, R.; Regnault, B.; Kun Tan, C.; Duszka, K.; Burcelin, R.; Wahli, W.; et al. High-Fat Diet Modifies the PPAR-γ Pathway Leading to Disruption of Microbial and Physiological Ecosystem in Murine Small Intestine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E5934–E5943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, E.; Drori, S.; Aiyer, A.; Yie, J.; Sarraf, P.; Chen, H.; Hauser, S.; Rosen, E.D.; Ge, K.; Roeder, R.G.; et al. Genetic Analysis of Adipogenesis through Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 41925–41930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ma, X.; Verma, N.K.; Wang, D.; Gavrilova, O.; Proia, R.L.; Finkel, T.; Mueller, E. Ablation of PPARγ in Subcutaneous Fat Exacerbates Age-Associated Obesity and Metabolic Decline. Aging Cell 2018, 17, e12721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisá, S.J.; Shike, D.W.; Faulkner, D.B.; Meteer, W.T.; Keisler, D.; Loor, J.J. Central Role of the PPARγ Gene Network in Coordinating Beef Cattle Intramuscular Adipogenesis in Response to Weaning Age and Nutrition. Gene Regul. Syst. Biol. 2014, 8, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yubero, P.; Manchado, C.; Cassard-Doulcier, A.M.; Mampel, T.; Viñas, O.; Iglesias, R.; Giralt, M.; Villarroya, F. CCAAT/Enhancer Binding Proteins Alpha and Beta Are Transcriptional Activators of the Brown Fat Uncoupling Protein Gene Promoter. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994, 198, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darlington, G.J.; Wang, N.; Hanson, R.W. C/EBP Alpha: A Critical Regulator of Genes Governing Integrative Metabolic Processes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1995, 5, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.D.; Finegold, M.J.; Bradley, A.; Ou, C.N.; Abdelsayed, S.V.; Wilde, M.D.; Taylor, L.R.; Wilson, D.R.; Darlington, G.J. Impaired Energy Homeostasis in C/EBP Alpha Knockout Mice. Science 1995, 269, 1108–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, E.D.; Hsu, C.-H.; Wang, X.; Sakai, S.; Freeman, M.W.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Spiegelman, B.M. C/EBPalpha Induces Adipogenesis through PPARgamma: A Unified Pathway. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Rosen, E.D.; Brun, R.; Hauser, S.; Adelmant, G.; Troy, A.E.; McKeon, C.; Darlington, G.J.; Spiegelman, B.M. Cross-Regulation of C/EBP Alpha and PPAR Gamma Controls the Transcriptional Pathway of Adipogenesis and Insulin Sensitivity. Mol. Cell 1999, 3, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.-Q.; Zhang, J.-W.; Daniel Lane, M. Sequential Gene Promoter Interactions of C/EBPbeta, C/EBPalpha, and PPARgamma during Adipogenesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 319, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, G.; Schneider, M.; Biemer-Daub, G.; Wied, S. Microvesicles Released from Rat Adipocytes and Harboring Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-Anchored Proteins Transfer RNA Stimulating Lipid Synthesis. Cell. Signal. 2011, 23, 1207–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrakusuma, I.; Sell, H.; Eckel, J. Novel Mediators of Adipose Tissue and Muscle Crosstalk. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2015, 4, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bechtel, T.J.; Reyes-Robles, T.; Fadeyi, O.O.; Oslund, R.C. Strategies for Monitoring Cell-Cell Interactions. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2021, 17, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.; Liu, T.; Yousuf, S.; Zhang, X.; Huang, W.; Li, A.; Xie, L.; Miao, X. Identification and Analysis of lncRNA, miRNA and mRNA Related to Subcutaneous and Intramuscular Fat in Laiwu Pigs. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1081460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, L.; Huang, D.; Wu, S.; Liu, S.; Wang, C.; Sheng, Y.; Lu, X.; Broxmeyer, H.E.; Wan, J.; Yang, L. Lipid Droplet-Associated lncRNA LIPTER Preserves Cardiac Lipid Metabolism. Nat. Cell Biol. 2023, 25, 1033–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, M.; Chen, B.; Calin, G.A. Exosomal lncRNAs as New Players in Cell-to-Cell Communication. Transl. Cancer Res. 2018, 7, S243–S252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravnskjaer, K.; Madiraju, A.; Montminy, M. Role of the cAMP Pathway in Glucose and Lipid Metabolism. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2016, 233, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balla, T. Phosphoinositides: Tiny Lipids with Giant Impact on Cell Regulation. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 1019–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, Y.; Cousins, R.S.; Liu, S.; Phelps, B.M.; Promes, J.A. Connecting Pancreatic Islet Lipid Metabolism with Insulin Secretion and the Development of Type 2 Diabetes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2020, 1461, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhou, X.; Xiong, L.; Pei, J.; Yao, X.; Liang, C.; Bao, P.; Chu, M.; Guo, X.; Yan, P. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Potential Role of Long Non-Coding RNAs in Mammary Gland of Yak During Lactation and Dry Period. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 579708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Hao, Q.; Prasanth, K.V. Nuclear Long Noncoding RNAs: Key Regulators of Gene Expression. Trends Genet. 2018, 34, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, M.-C.; Manor, O.; Wan, Y.; Mosammaparast, N.; Wang, J.K.; Lan, F.; Shi, Y.; Segal, E.; Chang, H.Y. Long Noncoding RNA as Modular Scaffold of Histone Modification Complexes. Science 2010, 329, 689–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ergun, S.; Oztuzcu, S. Oncocers: ceRNA-Mediated Cross-Talk by Sponging miRNAs in Oncogenic Pathways. Tumour Biol. J. Int. Soc. Oncodev. Biol. Med. 2015, 36, 3129–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.J.; Cases, S.; Jensen, D.R.; Chen, H.C.; Sande, E.; Tow, B.; Sanan, D.A.; Raber, J.; Eckel, R.H.; Farese, R.V. Obesity Resistance and Multiple Mechanisms of Triglyceride Synthesis in Mice Lacking Dgat. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; McFie, P.J.; Banman, S.L.; Brandt, C.; Stone, S.J. Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase-2 (DGAT2) and Monoacylglycerol Acyltransferase-2 (MGAT2) Interact to Promote Triacylglycerol Synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 28237–28248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisticò, C.; Pagliari, F.; Chiarella, E.; Fernandes Guerreiro, J.; Marafioti, M.G.; Aversa, I.; Genard, G.; Hanley, R.; Garcia-Calderón, D.; Bond, H.M.; et al. Lipid Droplet Biosynthesis Impairment through DGAT2 Inhibition Sensitizes MCF7 Breast Cancer Cells to Radiation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.-P.; Jin, X.; Zhang, J.-F.; Li, Q.; Yan, C.-G.; Li, X.-Z. Overexpression of DGAT2 Regulates the Differentiation of Bovine Preadipocytes. Animals 2023, 13, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-F.; Choi, S.-H.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Sun, B.; Tang, L.; Wang, E.-Z.; Hua, H.; Li, X.-Z. Overexpression of DGAT2 Stimulates Lipid Droplet Formation and Triacylglycerol Accumulation in Bovine Satellite Cells. Animals 2022, 12, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Guo, L.; Guo, Q.; Li, F. Research Progress on Molecular Mechanism of Muscle-Adipose Tissue Interaction Regulating Intramuscular Fat Deposition. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2023, 35, 4910–4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minokoshi, Y.; Kim, Y.-B.; Peroni, O.D.; Fryer, L.G.D.; Müller, C.; Carling, D.; Kahn, B.B. Leptin Stimulates Fatty-Acid Oxidation by Activating AMP-Activated Protein Kinase. Nature 2002, 415, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Yus, M.; Lopez-Perez, R.; Garcia-Sobreviela, M.P.; Del Moral-Bergos, R.; Lorente-Cebrian, S.; Arbones-Mainar, J.M. Adiponectin Overexpression in C2C12 Myocytes Increases Lipid Oxidation and Myofiber Transition. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 78, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The Biology, Function, and Biomedical Applications of Exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Xing, L.; Wu, J.; Wen, S.; Luo, J.; Chen, T.; Fan, Y.; Zhu, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, J.; et al. Skeletal Muscle-Derived Exosomal miR-146a-5p Inhibits Adipogenesis by Mediating Muscle-Fat Axis and Targeting GDF5-PPARγ Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reagent | Dosage | Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| SuperReal PreMix Plus (2×) | 5 μL | 1× |

| PCR Forward Primer (10 μM) | 0.3 μL | 0.3 μM |

| PCR Reverse Primer (10 μM) | 0.3 μL | 0.3 μM |

| cDNA | 1 μL | |

| ROX Reference Dye (50×) | 0.2 μL | 1× |

| ddH2O | 3.2 μL | |

| total | 10 μL |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meng, G.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Z.; Song, J.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, X.; Sun, M.; Yi, Y.; Xia, G. Bovine Adipocyte-Derived Exosomes Transport LncRNAs to Regulate Adipogenic Transdifferentiation of Bovine Muscle Satellite Cells. Animals 2025, 15, 3459. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233459

Meng G, Zhang J, Wu Z, Song J, Sun Q, Zhang X, Sun M, Yi Y, Xia G. Bovine Adipocyte-Derived Exosomes Transport LncRNAs to Regulate Adipogenic Transdifferentiation of Bovine Muscle Satellite Cells. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3459. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233459

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeng, Guangyao, Jiasu Zhang, Zewen Wu, Jixuan Song, Qian Sun, Xinxin Zhang, Mengxia Sun, Yang Yi, and Guangjun Xia. 2025. "Bovine Adipocyte-Derived Exosomes Transport LncRNAs to Regulate Adipogenic Transdifferentiation of Bovine Muscle Satellite Cells" Animals 15, no. 23: 3459. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233459

APA StyleMeng, G., Zhang, J., Wu, Z., Song, J., Sun, Q., Zhang, X., Sun, M., Yi, Y., & Xia, G. (2025). Bovine Adipocyte-Derived Exosomes Transport LncRNAs to Regulate Adipogenic Transdifferentiation of Bovine Muscle Satellite Cells. Animals, 15(23), 3459. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233459