Ontogeny of Melatonin Secretion and Functional Maturation of the Pineal Gland in the Embryonic Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo)

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Embryos

2.2. In Vitro Study

2.2.1. Culture Medium

2.2.2. Superfusion Culture Technique

2.3. Experimental Design

2.3.1. Experiment I—Effect of Light

2.3.2. Experiment II—Activity of the Endogenous Oscillator

2.3.3. Experiment III—Effect of Norepinephrine

2.4. Analytical Procedures

2.4.1. Chemicals

2.4.2. Melatonin Radioimmunoassay

2.4.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

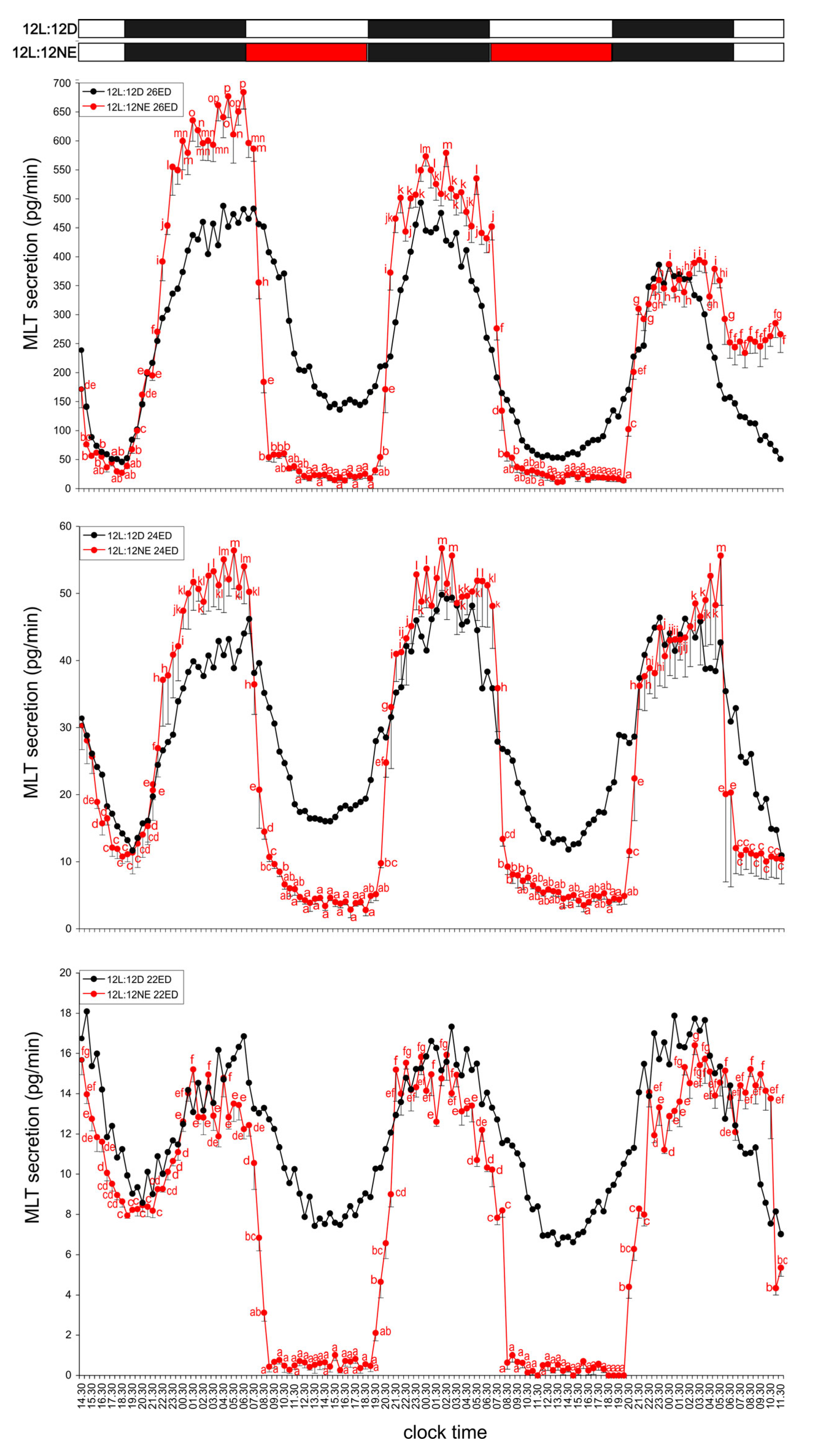

3.1. Experiment I—Effect of Light

3.1.1. Group I—12L:12D Cycle

3.1.2. Group II—12D:12L Cycle

3.1.3. Group III—Three-Hour Light Exposure at Night

3.2. Experiment II—Activity of the Endogenous Oscillator

3.2.1. Group IV—24D Cycle (Continuous Darkness)

3.2.2. Group V—24L Cycle (Continuous Light)

3.3. Experiment III—Effect of Norepinephrine

3.3.1. Group VI—NE During the Second and Third Subjective Days

3.3.2. Group VII—Three-Hour NE Exposure at Night

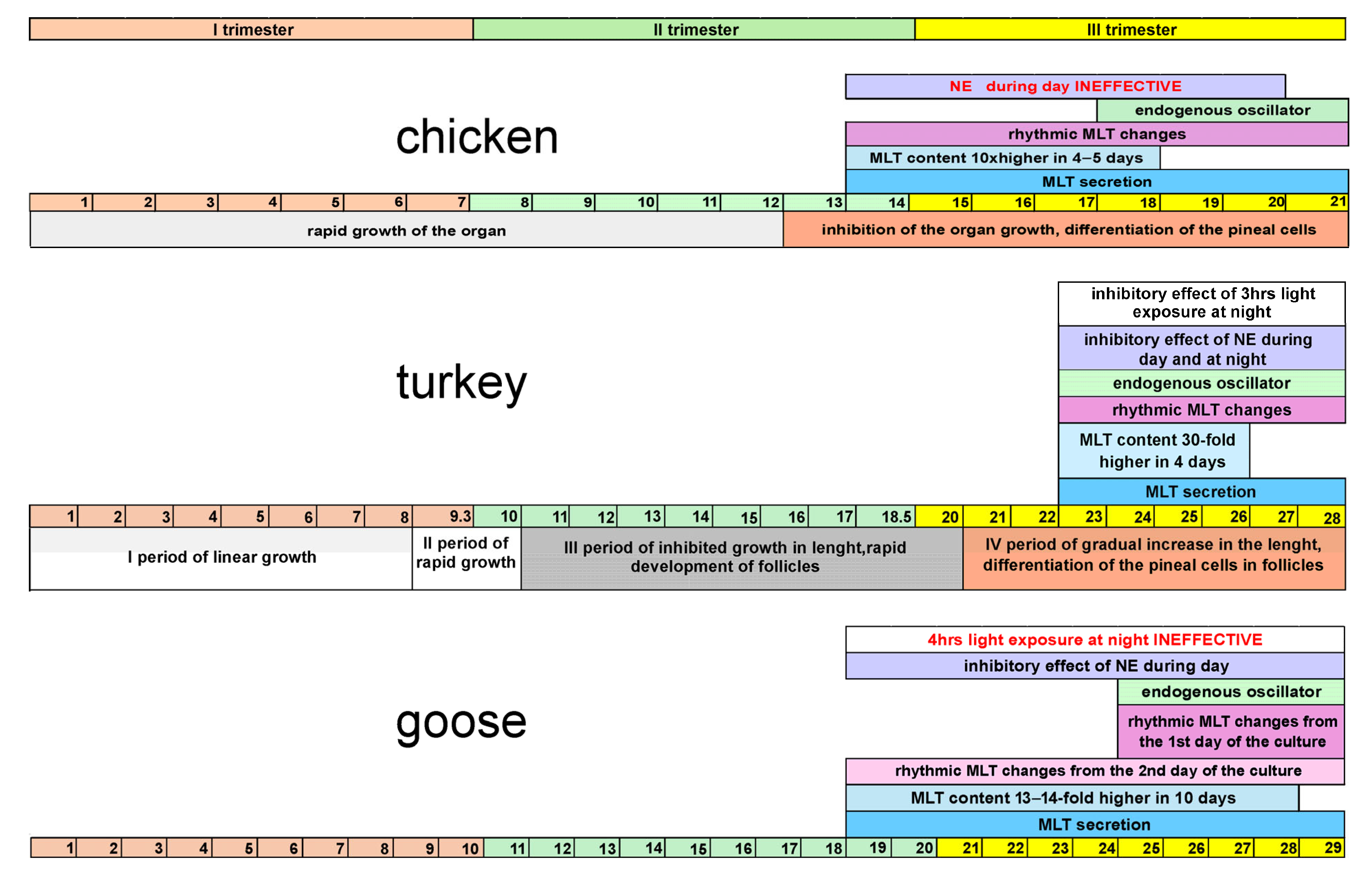

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adamska, I.; Lewczuk, B.; Markowska, M.; Majewski, P.M. Daily profiles of melatonin synthesis-related indoles in the pineal glands of young chickens. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2016, 164, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boya, J.; Calvo, J. Post-hatching evolution of the pineal gland of the chicken. Acta Anat. 1978, 101, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanuszewska-Dominiak, M.; Martyniuk, K.; Lewczuk, B. Embryonic development of avian pineal secretory activity—A lesson from the goose pineal organs in superfusion culture. Molecules 2021, 26, 6329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiecińska, K.; Hanuszewska, M.; Petrusewicz-Kosińska, M. Pineal organ of the Muscovy duck. Med. Wet. 2017, 73, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewczuk, B.; Ziółkowska, N.; Prusik, M.; Przybylska-Gornowicz, B. Diurnal profiles of melatonin synthesis-related indoles, catecholamines and their metabolites in the duck pineal organ. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 12604–12630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maronde, E.; Stehle, J.H. The mammalian pineal gland: Known facts, unknown facets. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 18, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyniuk, K.; Hanuszewska, M.; Lewczuk, B. Metabolism of melatonin synthesis-related indoles in the turkey pineal organ and its modification by monochromatic light. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyniuk, K.; Hanuszewska-Dominiak, M.; Lewczuk, B. Changes in the Metabolic Profile of Melatonin-Synthesis-Related Indoles during Post-Embryonic Development of the Turkey Pineal Organ. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, K.; Hiramatsu, K. Pineal organ of birds: Morphology and function. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1993, 55, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Petrusewicz-Kosińska, M.; Przybylska-Gornowicz, B.; Ziółkowska, N.; Martyniuk, K.; Lewczuk, B. Developmental morphology of the turkey pineal organ: Immunocytochemical and ultrastructural studies. Micron 2019, 122, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piesiewicz, A.; Podobas, E.; Kędzierska, U.; Joachimiak, E.; Markowska, M.; Majewski, P.; Skwarło-Sońta, K. Season-related differences in the biosynthetic activity of the neonatal chicken pineal gland. Open Ornithol. J. 2010, 3, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusik, M.; Lewczuk, B.; Nowicki, M.; Przybylska-Gornowicz, B. Histology and ultrastructure of the pineal organ of the domestic goose. Histol. Histopathol. 2006, 21, 1075–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusik, M.; Lewczuk, B.; Ziółkowska, N.; Przybylska-Gornowicz, B. Regulation of melatonin secretion in the pineal organ of the domestic duck—An in vitro study. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2015, 18, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusik, M.; Lewczuk, B. Roles of direct photoreception and the internal circadian oscillator in the regulation of melatonin secretion in the pineal organ of the domestic turkey: A novel in vitro clock and calendar model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusik, M.; Lewczuk, B. Diurnal rhythm of plasma melatonin concentration in the domestic turkey and its regulation by light and endogenous oscillators. Animals 2020, 10, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylska-Gornowicz, B.; Lewczuk, B.; Prusik, M.; Nowicki, M. Post-hatching development of the turkey pineal organ: Histological and immunohistochemical studies. Neuroendocrinol. Lett. 2005, 26, 383–392. [Google Scholar]

- Przybylska-Gornowicz, B.; Lewczuk, B.; Prusik, M.; Kalicki, M.; Ziółkowska, N. Morphological studies of the pineal gland in the common gull (Larus canus) reveal uncommon features of pinealocytes. Anat. Rec. 2012, 295, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollrath, L. The Pineal Organ; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Ziółkowska, N.; Lewczuk, B.; Prusik, M. Diurnal and circadian variations in indole contents in the goose pineal gland. Chronobiol. Int. 2018, 35, 1560–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziółkowska, N.; Lewczuk, B. Norepinephrine is a major regulator of pineal gland secretory activity in the domestic goose (Anser anser). Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 664117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, J.; Boya, J. Embryonic development of the pineal gland of the chicken (Gallus gallus). Acta Anat. 1978, 101, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.; Gibson, M.A. A histological and histochemical study of the development of the pineal gland in the chick, Gallus domesticus. Can. J. Zool. 1970, 48, 1321–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jové, M.; Cobos, P.; Torrente, M.; Gilabert, R.; Piera, V. Embryonic development of pineal gland vesicles: A morphological and morphometrical study in chick embryos. Eur. J. Morphol. 1999, 37, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusik, M. Developmental morphology of the turkey pineal gland in histological images and 3D models. Micron 2022, 153, 103196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, J.; Boya, J. Ultrastructural study of the embryonic development of the pineal gland of the chicken (Gallus gallus). Acta Anat. 1979, 103, 39–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, W.; Möller, G. Structural and functional differentiation of the embryonic chick pineal organ in vivo and in vitro: A scanning electron-microscopic and radioimmunoassay study. Cell Tissue Res. 1990, 260, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeman, M.; Herichová, I. Circadian melatonin production develops faster in birds than in mammals. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2011, 172, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeman, M.; Gwinner, E.; Somogyiová, E. Development of melatonin rhythm in the pineal gland and eyes of chick embryo. Experientia 1992, 48, 765–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeman, M.; Gwinner, E.; Herichová, I.; Lamošová, D.; Koštál, L. Perinatal development of circadian melatonin production in domestic chicks. J. Pineal Res. 1999, 26, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeman, M.; Pavlik, P.; Lamošová, D.; Herichová, I.; Gwinner, E. Entrainment of rhythmic melatonin production by light and temperature in the chick embryo. Avian Poult. Biol. Rev. 2004, 15, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akasaka, K.; Nasu, T.; Katayama, T.; Murakami, N. Development of regulation of melatonin release in pineal cells in chick embryo. Brain Res. 1995, 692, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csernus, V.J.; Nagy, A.D.; Faluhelyi, N. Development of the rhythmic melatonin secretion in the embryonic chicken pineal gland. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2007, 152, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamošová, D.; Zeman, M.; Macková, M.; Gwinner, E. Development of rhythmic melatonin synthesis in cultured pineal glands and pineal cells isolated from chick embryo. Experientia 1995, 51, 970–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drozdova, A.; Okuliarova, M.; Zeman, M. The effect of different wavelengths of light during incubation on the development of rhythmic pineal melatonin biosynthesis in chick embryos. Animal 2019, 13, 1635–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faluhelyi, N.; Csernus, V. The effects of environmental illumination on the in vitro melatonin secretion from the embryonic and adult chicken pineal gland. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2007, 152, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faluhelyi, N.; Reglodi, D.; Csernus, V. Development of the circadian melatonin rhythm and its responsiveness to PACAP in the embryonic chicken pineal gland. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1040, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faluhelyi, N.; Matkovits, A.; Párniczky, A.; Csernus, V. The in vitro and in ovo effects of environmental illumination and temperature on the melatonin secretion from the embryonic chicken pineal gland. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1163, 383–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, C.; Araki, M. Morphometric analysis of photoreceptive, neuronal and endocrinal cell differentiation of avian pineal cells: An in vitro immunohistochemical study on the developmental transition from neuronal to photo-endocrinal property. Zool. Sci. 2002, 19, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanuszewska, M.; Prusik, M.; Lewczuk, B. Embryonic ontogeny of 5-hydroxyindoles and 5-methoxyindoles synthesis pathways in the goose pineal organ. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herichová, I.; Monosíková, J.; Zeman, M. Ontogeny of melatonin, Per2 and E4bp4 light responsiveness in the chicken embryonic pineal gland. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 2008, 149, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommedal, S.; Csernus, V.; Nagy, A.D. The embryonic pineal gland of the chicken as a model for experimental jet lag. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2013, 188, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macková, M.; Lamošová, D.; Zeman, M. Regulation of rhythmic melatonin production in pineal cells of chick embryo by cyclic AMP. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1998, 54, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obłap, R.; Olszańska, B. Presence and developmental regulation of serotonin N-acetyltransferase transcripts in oocytes and early quail embryos (Coturnix coturnix japonica). Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2003, 65, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obłap, R.; Olszańska, B. Transition from embryonic to adult transcription pattern of serotonin N-acetyltransferase gene in avian pineal gland. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2004, 67, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszańska, B.; Majewski, P.; Lewczuk, B.; Stępińska, U. Melatonin and its synthesizing enzymes (arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase-like and hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase) in avian eggs and early embryos. J. Pineal Res. 2007, 42, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassone, V.M.; Menaker, M.; Woodlee, G.L. Hypothalamic regulation of circadian noradrenergic input to the avian pineal gland. J. Comp. Physiol. A 1990, 167, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, M.; Fukada, Y.; Shichida, Y.; Yoshizawa, T.; Tokunaga, F. Differentiation of both rod and cone types of photoreceptors in the in vivo and in vitro developing pineal glands of the quail. Dev. Brain Res. 1992, 65, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prusik, M. Ontogeny of Melatonin Secretion and Functional Maturation of the Pineal Gland in the Embryonic Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo). Animals 2025, 15, 3437. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233437

Prusik M. Ontogeny of Melatonin Secretion and Functional Maturation of the Pineal Gland in the Embryonic Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo). Animals. 2025; 15(23):3437. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233437

Chicago/Turabian StylePrusik, Magdalena. 2025. "Ontogeny of Melatonin Secretion and Functional Maturation of the Pineal Gland in the Embryonic Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo)" Animals 15, no. 23: 3437. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233437

APA StylePrusik, M. (2025). Ontogeny of Melatonin Secretion and Functional Maturation of the Pineal Gland in the Embryonic Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo). Animals, 15(23), 3437. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233437