Construing Complex Referentiality in Interspecies Interaction: Embodiment and Biosemiotics

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Human–Animal Semiotics and Referentiality

1.2. Approaching Interspecies Language Use from the Perspective of Embodiment and Biosemiotics

1.3. Research Questions and Hypotheses

- Q1.

- Does the amount of children’s pet-directed speech vary according to the ongoing activity and language complexity, including referentiality?

- Q2.

- If there is referential complexity, how is it treated by participants of different species in child–pet interaction?

- H1.

- Yes, the amount of speech varies according to the type of activity and referential complexity.

- H2.

- In middle childhood, a human child can show their awareness of the differences between human and other-than-human semiotic worlds and tailor their expressions to make them more accessible to their animal companions.

2. Materials and Methods

- (1)

- ici‘here’

- (2)

- wouah wouah‘woof woof’

- (3)

- ah t’aimes bien‘oh you like that’

- (4)

- cherche pas y a rien à faire‘don’t even try it’s no use’

- (5)

- là tu sais les canards que je t’ai montrés ils étaient à moi quand j’étais petite‘and you know the ducks that I showed you they were mine when I was little’

- Demonstrative reference;

- Past- and future-time reference;

- Conditionality;

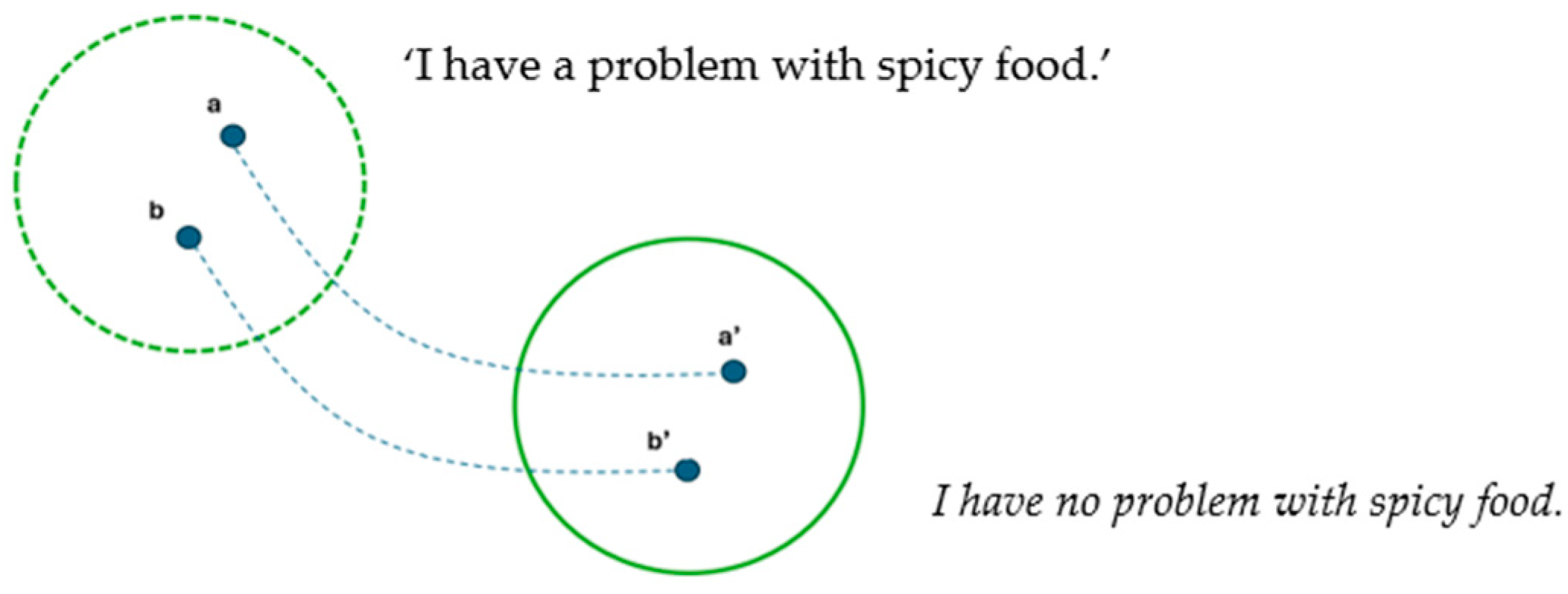

- Reference to absent entities (including wh-questions);

- Expressions of alternatives;

- Reported speech and thoughts.

3. Results

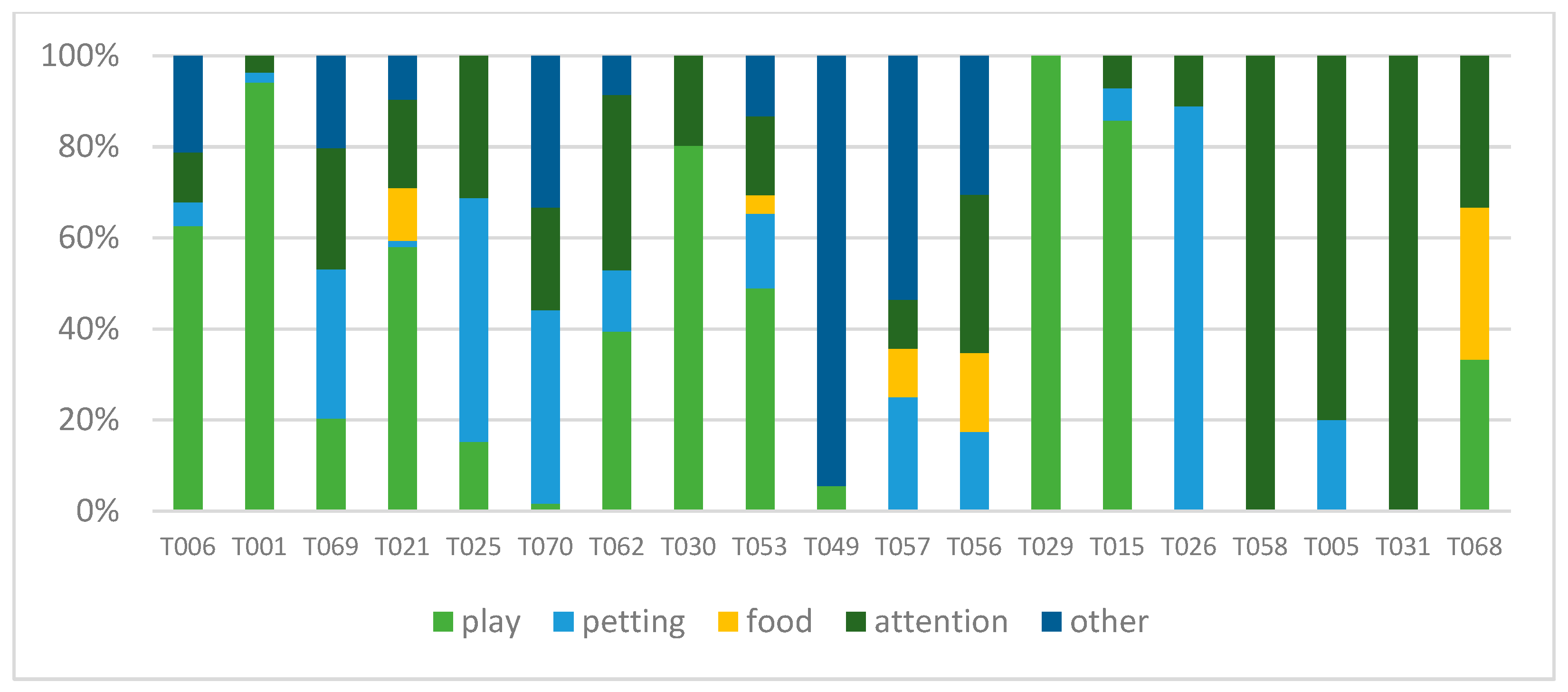

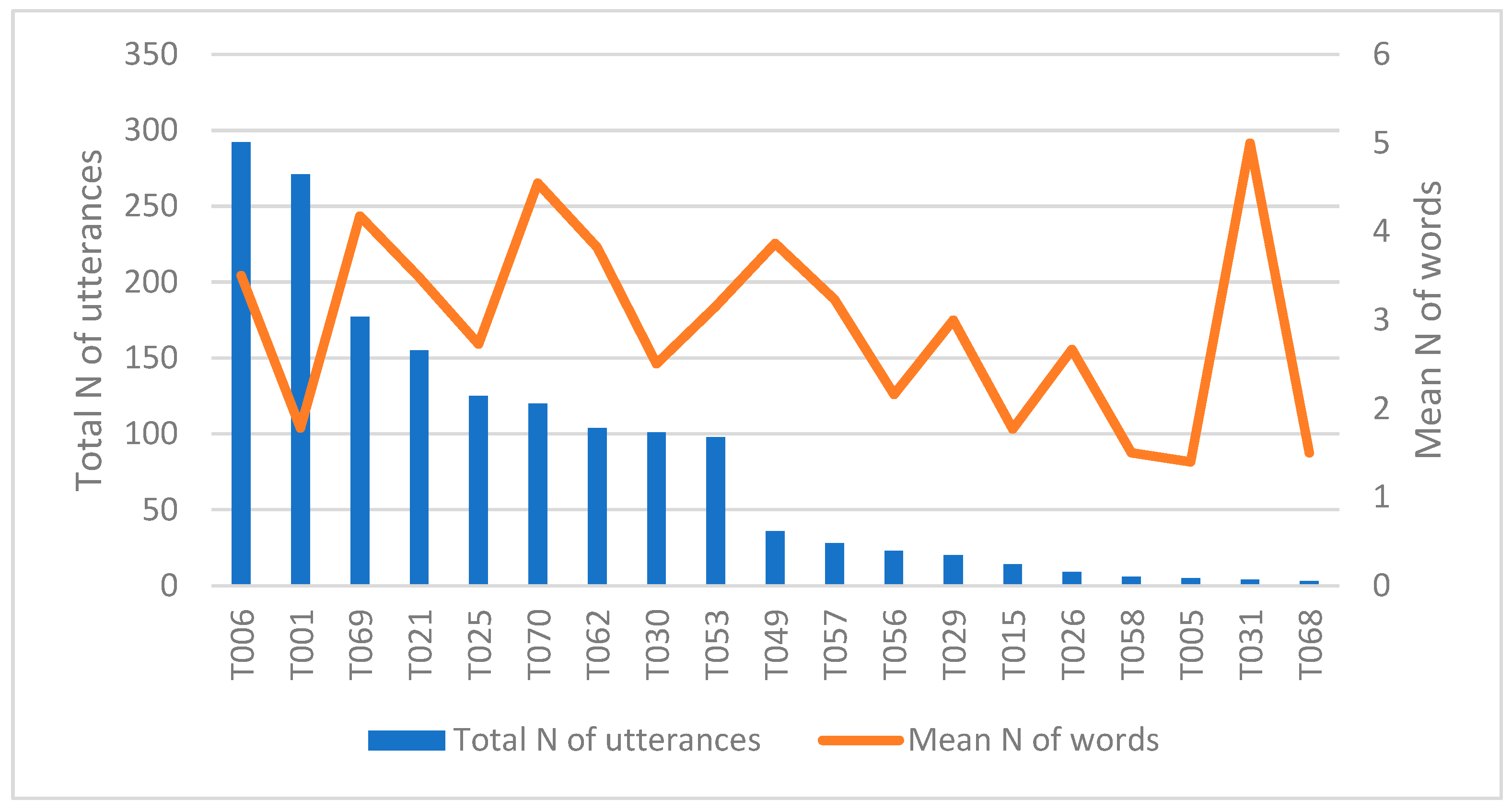

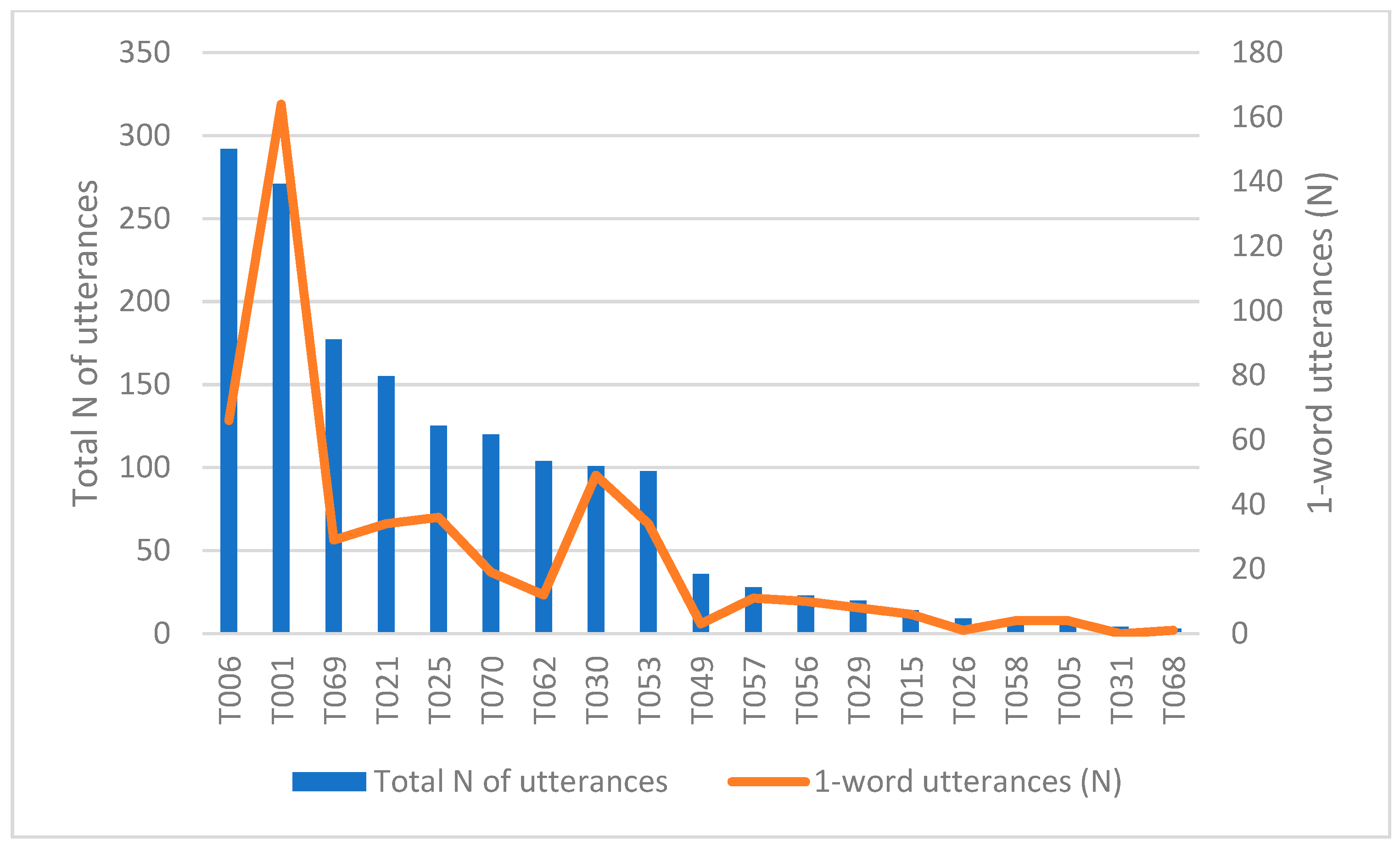

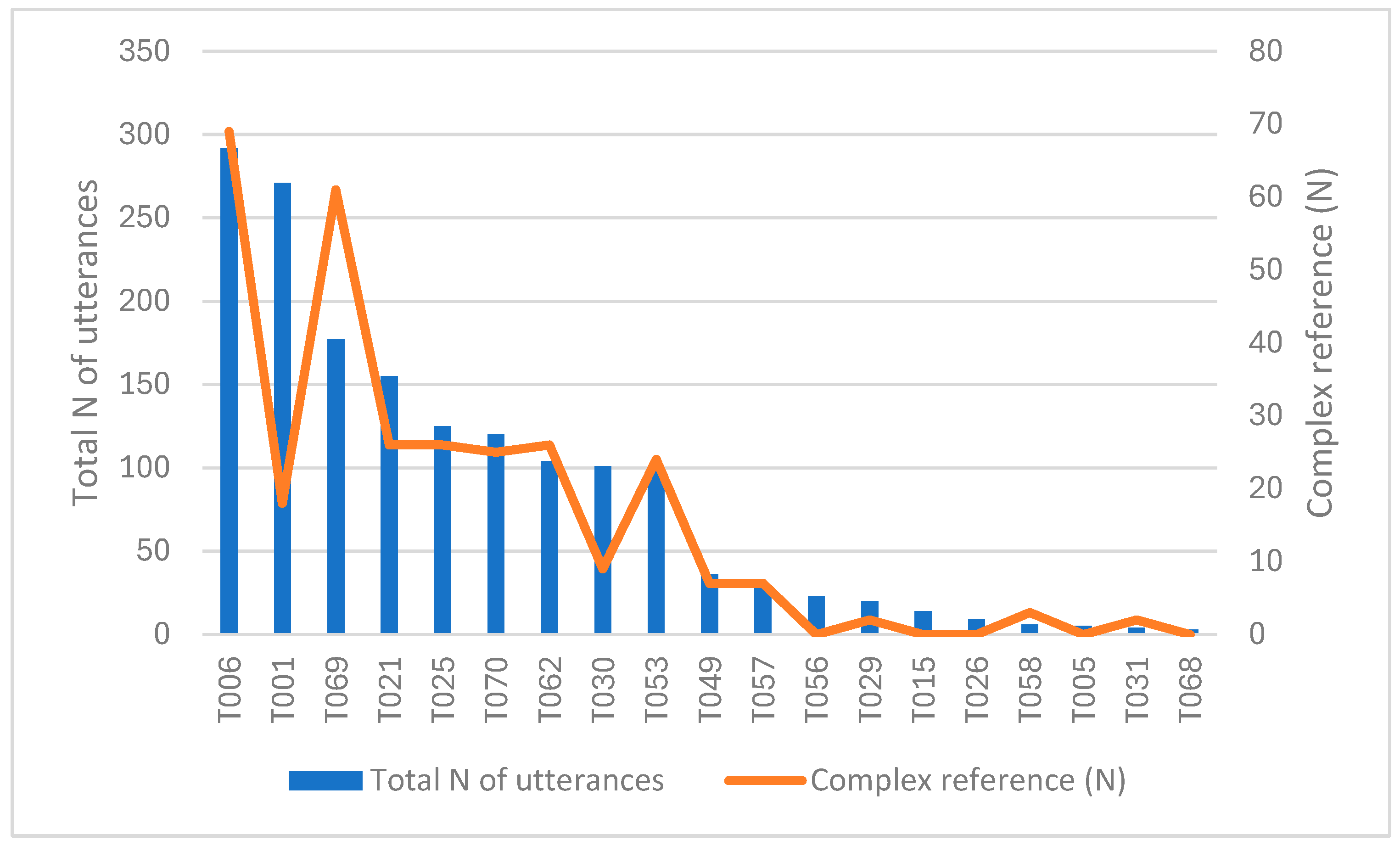

3.1. Children’s Pet-Directed Speech

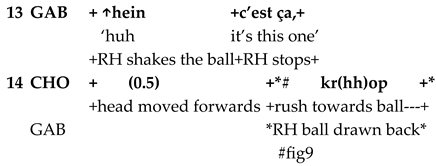

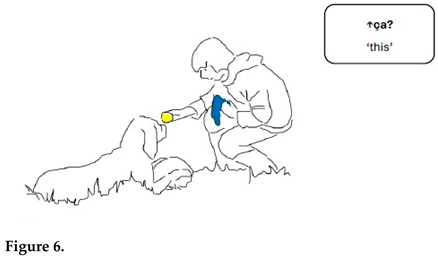

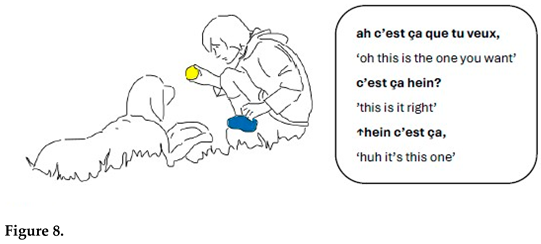

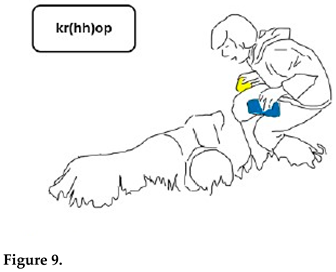

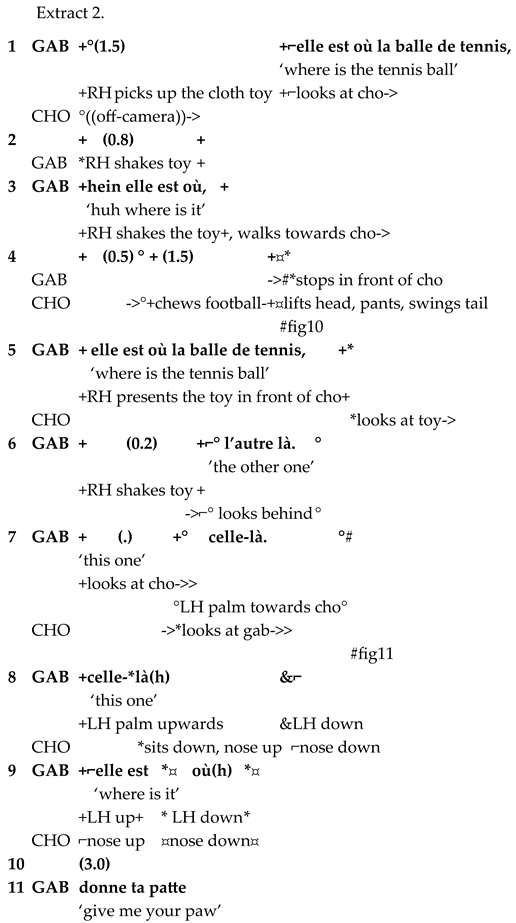

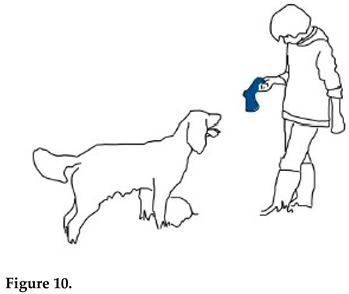

3.2. Referential Complexity in Play Interaction

4. Discussion

- Q1.

- Does the amount of children’s pet-directed speech vary according to the ongoing activity and language complexity, including referentiality?

- Q2.

- If there is referential complexity, how is it treated by participants of different species in child–pet interaction?

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Talk | |

| . | falling final intonation |

| ? | rising final intonation |

| , | level final intonation |

| ↑/↓ | rise / fall in pitch |

| <speak> | slow pace |

| (h) | breathiness |

| (.) | micropause |

| (0.5) | pause in seconds |

| (( )) | transcriber’s commentary |

| Embodied conduct | |

| * * / + + / ° ° | Descriptions of embodied movements are delimited between |

| two identical symbols and are synchronized with corresponding | |

| stretches of talk/lapses of time. | |

| -> | Action continues across subsequent lines until next identical symbol (->*). |

| >> | Action begins before the excerpt. |

| ->> | Action continues after the excerpt. |

| ….. | preparation |

| ------ | apex |

| ,,,,,,,, | retraction |

| fig, # | screenshot and its timing |

| RH | right hand |

| LH | left hand |

References

- Peltola, R.; Simonen, M. Towards interspecies pragmatics: Language use and embodied interaction in human-animal activities. J. Pragmat. 2024, 220, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepek Reed, B.; Lundesjö Kvart, S. The role of horses as instructional and diagnostic partners in riding lessons. Animals 2025, 15, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondémé, C. Quand les animaux participant à l’interaction sociale: Nouveaux regards sur l’analyse séquentielle. Lang. Société 2022, 176, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondémé, C. Sequence organization in human–animal interaction: An exploration of two canonical sequences. J. Pragmat. 2023, 214, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjunpää, K. Repetition and prosodic matching in responding to pets’ vocalizations. Lang. Société 2022, 176, 69–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonen, M. Dogs responding to human utterances in embodied ways. J. Pragmat. 2023, 217, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepek Reed, B. Designing talk for humans and horses: Prosody as a resource for parallel recipient design. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 2023, 56, 89–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, M. Taking turns across channels: Conversation-analytic tools in animal communication. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 80, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pika, S.; Wilkinson, R.; Kendrick, K.H.; Vernes, S.C. Taking turns: Bridging the gap between human and animal communication. Proc. R. Soc. B 2018, 285, 20180598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miklósi, A.; Topál, J. What does it take to become ‘best friends’? Evolutionary changes in canine social competence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2013, 17, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haraway, D.J. When Species Meet; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Quaranta, A.; d’Ingeo, S.; Amoruso, R.; Siniscalchi, M. Emotion recognition in cats. Animals 2020, 10, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siniscalchi, M.; d’Ingeo, S.; Fornellli, S.; Quaranta, A. Lateralized behavior and cardiac activity of dogs in response to human emotional vocalizations. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehoczki, F.; Pérez Fraga, P.; Andics, A. Family pigs’ and dogs’ reactions to human emotional vocalizations: A citizen science study. Anim. Behav. 2024, 214, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, A.; Shinozuka, K. Vocal recognition of owners by domestic cats (Felis catus). Anim. Cogn. 2013, 16, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, S.; Chijiiwa, H.; Arahori, M.; Saito, A.; Fujita, K.; Kuroshima, H. Socio-spatial cognition in cats: Mentally mapping owner’s location from voice. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, A.; Shinozuka, K.; Ito, Y.; Hasegawa, T. Domestic cats (Felis catus) discriminate their names from other words. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takagi, S.; Saito, A.; Arahori, M.; Chijiiwa, H.; Koyasu, H.; Nagasawa, M.; Kikusui, T.; Fujita, K.; Kuroshima, H. Cats learn the names of their friend cats in their daily lives. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuaya, L.V.; Hernandéz-Pérez, R.; Boros, M.; Deme, A.; Andics, A. Speech naturalness detection and language representation in the dog brain. NeuroImage 2022, 248, 118811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pongrácz, P.; Molnár, C.; Miklósi, A. Acoustic parameters of dog barks carry emotional information for humans. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2006, 100, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R. Dog talk: Dogs and humans barking and growling during interspecies play. Interact. Stud. 2023, 24, 484–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mouzon, C.; Di-Stasi, R.; Leboucher, G. Human perception of cats’ communicative cues: Human-cat communication goes multimodal. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2024, 27, 0106137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mouzon, C.; Leboucher, G. Multimodal communication in the human-cat relationship: A pilot study. Animals 2023, 19, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mouzon, C.; Gonthier, M.; Leboucher, G. Discrimination of cat-directed speech from human-directed speech in a population of indoor companion cats (Felis catus). Anim. Cogn. 2023, 26, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.A.; Delude, L.A. Behavior of young children in the presence of different kinds of animals. Anthrozoös 1989, 3, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandgeorge, M.; Gautier, Y.; Bourreau, Y.; Mossu, H.; Hausberger, M. Visual attention patterns differ in dog vs. cat interactions with children with typical development or autism spectrum disorders. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pongrácz, P.; Molnár, C.; Miklósi, A. Barking in family dogs: An ethological approach. Vet. J. 2010, 183, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, J.; Rooney, N. Dog social behavior and communication. In The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behavior and Interactions with People; Serpell, J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 133–159. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, T.; Proops, L.; Forman, J.; Spooner, R.; McComb, K. The role of cat eye narrowing movements in cat–human communication. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.W. Americans’ talk to dogs: Similarities and differences with talk to infants. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 2001, 34, 183–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jääskeläinen, A. ‘But for calves we were sweeter’: Traditional Finnish cattle calling as trans-species pidgin. Lang. Commun. 2025, 103, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasello, M. Becoming Human: A Theory of Ontogeny; The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Peltola, R.; Wu, Y.; Grandgeorge, M. Interpersonal distance, mouth sounds, and referentiality in child-dog play: A pluridisciplinary approach. Lang. Commun. 2025, 103, 126–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, A. Attention to attention in domestic dog (Canis familiaris) dyadic play. Anim. Cogn. 2009, 12, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, A.; Slocombe, K. ‘Who’s a good boy?!’ Dogs prefer naturalistic dog-directed speech. Anim. Cogn. 2018, 21, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, S.; Koyasu, H.; Nagasawa, M.; Kikusui, T. Rapid formation of picture-word association in cats. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongrácz, P.; Szulamit Szapu, J.; Faragó, T. Cats (Felis silvestris catus) read human gaze for referential information. Intelligence 2019, 74, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, M.A.; Udell, M.A.R.; Leavens, D.A.; Skopos, L. Animal pointing: Changing trends and findings from 30 years of research. J. Comp. Psychol. 2018, 132, 326–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faragó, T.; Pongrácz, P.; Range, F.; Virányi, Z.; Miklósi, A. ‘The bone is mine’: Affective and referential aspects of dog growls. Anim. Behav. 2010, 79, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongrácz, P.; Dobos, P.; Zsilák, B.; Faragó, T.; Ferdinandy, B. ‘Beware, I am large and dangerous’: Human listeners can be deceived by dynamic manipulation of the indexical content of agonistic dog growls. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2024, 78, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornips, L.; Van Koppen, M.; Leufkens, S.; Melum Eide, K.; Van Zijverden, R. A linguistic-pragmatic analysis of cat-induced deixis in cat-human interactions. J. Pragmat. 2023, 217, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirce, C.S. Collected Papers: Volume II, Elements of Logic; Hartshorne, C., Weiss, P., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Hockett, C.F. The origin of speech. Sci. Am. 1960, 203, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauconnier, G. Mappings in Thought and Language; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fauconnier, G.; Turner, M. The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn, E. How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jääskeläinen, A. Mimetic schemas and shared perception through imitatives. Nord. J. Linguist. 2016, 39, 159–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepperberg, I.M. Animal language studies: What happened? Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2017, 24, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, S.E.G.; Osthaus, B. In what sense are dogs special? Canine cognition in comparative context. Learn. Behav. 2018, 46, 335–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, L.; Lonardo, L. Canine perspective-taking. Anim. Cogn. 2023, 26, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritvo, H. On the animal turn. Dedalus 2007, 136, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornips, L. The animal turn in postcolonial (socio)linguistics: The interspecies greeting of the dairy cow. J. Postcolonial Linguist. 2022, 6, 210–232. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M. The embodiment of language. In The Oxford Handbook of 4E Cognition; Newen, A., De Bruin, L., Gallagher, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 623–639. [Google Scholar]

- Von Uexküll, J. The theory of meaning. In Readings in Zoosemiotics; Maran, T., Martinelli, D., Turovsk, A., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Paveau, M.A. Ce que disent les objets: Sens, affordance, cognition. Synerg. Pays Riverains Balt. 2012, 9, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Jääskeläinen, A. Linguistic and material ways of communicating with cows—The dung pusher as a semiotic resource. Under review. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Fultot, M.; Turvey, M.T. Von Uexküll’s Theory of Meaning and Gibson’s Organism–Environment Reciprocity. Ecol. Psychol. 2019, 31, 289–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgat, F. La construction des mondes animaux et du monde humain selon Jacob von Uexküll. In Homme et Animal, la Question des Frontières; Camos, V., Cézilly, F., Sylvestre, J.P., Eds.; Éditions Quæ: Versailles, France, 2009; pp. 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Tønnessen, M. The evolutionary origin(s) of the Umwelt. Biosemiotics 2022, 15, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melson, G.F. Play between children and domestic animals. In Play as Engagement and Communication; Enwokah, E., Ed.; University Press of America: Lanham, MD, USA, 2010; pp. 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mondada, L. Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: Challenges for transcribing multimodality. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 2018, 51, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, M.L.; Smolik, F.; Perpich, D.; Thompson, T.; Rytting, N.; Blossom, M. Mean length of utterance levels in 6-month intervals for children 3 to 9 years with and without language impairments. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2010, 53, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnedecker, C. De l’un à l’autre et réciproquement... Aspects sémantiques, discursifs et cognitifs des pronoms anaphoriques corrélés; l’un/l’autre et le premier/le second; De Boeck Supérieur: Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- De Mulder, W. Le déterminant démonstratif ce: d’un marqueur token-réflexif à une instruction contribuant à la construction de référents. Lang. Française 2021, 210, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mulder, W.; Guillot, C.; Mortelmans, J. Ce N-ci et ce N-là en moyen français. In Déterminants en Diachronie et Synchronie; Tovena, L., Ed.; Projet ELICO Publications: Paris, France, 2010; pp. 86–103. [Google Scholar]

- Zlatev, J.; Mouratidou, A. Extending the life world: Phenomenological triangulation along two planes. Biosemiotics 2024, 17, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Video | Child/ Sex | Child/Age (yrs) | Pet/ Species | Pet/Breed | Pet/Sex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T001 | F | 11 | 1 dog | Boxer | F |

| T005 | F | 6 | 1 cat | Domestic shorthair cat | M |

| T006 | M | 11 | 1 dog | French spaniel | F |

| T015 | M | 9 | 1 dog | Cavalier King Charles | M |

| T021 | M | 8 | 1 dog, 1 cat | Boxer, N/A | M, N/A |

| T025 | F | 12 | 1 cat | Angora | F |

| T026 | M | 8 | 1 cat | Domestic shorthair cat | M |

| T029 | M | 9 | 1 cat | N/A | M |

| T030 | F | 7 | 1 dog | Newfoundland | M |

| T031 | M | 7 | 1 dog | Mixed breed | M |

| T049 | M | 7 | 1 dog | Rottweiler | M |

| T053 | F | 11 | 2 cats | Domestic shorthair cat | M |

| T056 | M | 9 | 1 dog | Groendale | M |

| T057 | M | 12 | 1 dog | Groendale | M |

| T058 | M | 11 | 1 dog | Golden retriever | F |

| T062 | F | 6 | 1 dog | Lhassa Apso | M |

| T068 | M | 10 | 1 cat | Siamese | M |

| T069 | F | 7 | 1 dog, 2 cats | Lhassa Apso, Chartreux | F, N/A |

| T070 | F | 11 | 1 cat | Domestic shorthair cat | F |

| Video | Child/ Sex | Child/ Age (yrs) | Cat/ Utterances | Dog/ Utterances | Total N of Utterances |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T006 | M | 11 | N/A | 292 | 292 |

| T001 | F | 11 | N/A | 271 | 271 |

| T069 | F | 7 | 160 | 17 | 177 |

| T021 | M | 8 | 19 | 136 | 155 |

| T025 | F | 12 | 125 | N/A | 125 |

| T070 | F | 11 | 120 | N/A | 120 |

| T062 | F | 6 | N/A | 104 | 104 |

| T030 | F | 7 | N/A | 101 | 101 |

| T053 | F | 11 | 98 | N/A | 98 |

| T049 | M | 7 | N/A | 36 | 36 |

| T057 | M | 12 | N/A | 28 | 28 |

| T056 | M | 9 | N/A | 23 | 23 |

| T029 | M | 9 | 20 | N/A | 20 |

| T015 | M | 9 | N/A | 14 | 14 |

| T026 | M | 8 | 9 | N/A | 9 |

| T058 | M | 11 | N/A | 6 | 6 |

| T005 | F | 6 | 5 | N/A | 5 |

| T031 | M | 7 | N/A | 4 | 4 |

| T068 | M | 10 | 3 | N/A | 3 |

| Cats | Dogs | |

|---|---|---|

| Total N of individuals | 11 | 12 |

| Total N of utterances addressed | 559 | 1032 |

| Mean N of utterances addressed/individual | 50.8 | 86.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peltola, R.; Grandgeorge, M. Construing Complex Referentiality in Interspecies Interaction: Embodiment and Biosemiotics. Animals 2025, 15, 3430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233430

Peltola R, Grandgeorge M. Construing Complex Referentiality in Interspecies Interaction: Embodiment and Biosemiotics. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233430

Chicago/Turabian StylePeltola, Rea, and Marine Grandgeorge. 2025. "Construing Complex Referentiality in Interspecies Interaction: Embodiment and Biosemiotics" Animals 15, no. 23: 3430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233430

APA StylePeltola, R., & Grandgeorge, M. (2025). Construing Complex Referentiality in Interspecies Interaction: Embodiment and Biosemiotics. Animals, 15(23), 3430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233430