The Impact of MEI1 Alternative Splicing Events on Spermatogenesis in Mongolian Horses

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Material

2.2. Construction of Overexpression Lentiviral Vectors

- HT1080 cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 8.0 × 104 cells per well and cultured for 24 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2;

- Viral stock was serially diluted to 50 µL, 0.5 µL, and 0.05 µL gradients;

- Culture medium was replaced with MEM containing 4% FBS and the diluted virus; each dilution was assayed in duplicate;

- After 24 h of infection, the medium was replaced with fresh medium;

- Genomic DNA was extracted 72 h post-infection, and viral titer was determined by quantitative PCR.

2.3. Lentiviral Infection of Sertoli Cells

2.4. Detection of MEI1 Expression in the MXE and SE Groups by qRT-PCR at 72 h

2.5. Transcriptome Analysis and Data Processing

2.6. Metabolomics Analysis and Data Processing

2.7. Combined Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis

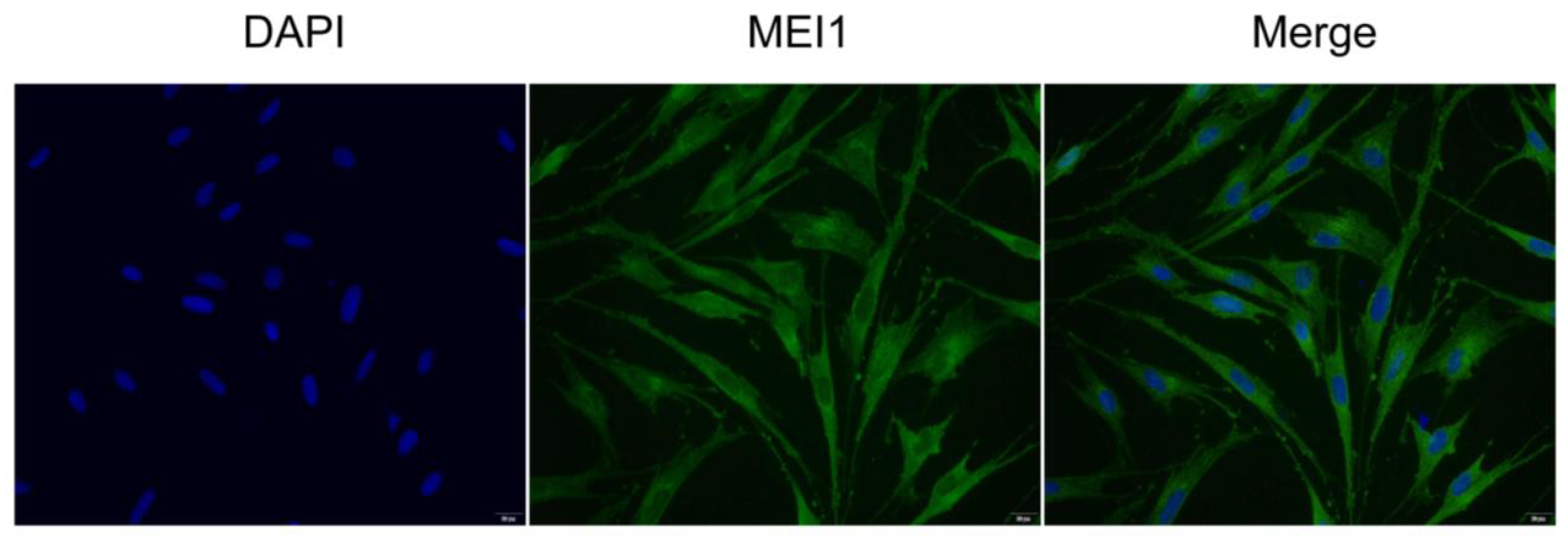

2.8. Subcellular Localization of MEI1 in Sertoli Cells

- (1)

- Cell seeding: Third-passage Sertoli cells were seeded on coverslips in 24-well plates. After 24 h of culture, when cells reached approximately 50% confluence, they were washed three times with PBS (5 min each) on a shaking platform.

- (2)

- Fixation: Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 30 min, followed by three PBS washes (5 min each).

- (3)

- Permeabilization: Cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton™ X-100 at room temperature for 30 min, then washed three times with PBS.

- (4)

- Blocking: Blocking was carried out with 5% BSA in PBS at room temperature for 1 h.

- (5)

- Primary antibody incubation: After removal of blocking solution, cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-MEI1 mouse monoclonal antibody (1:200) diluted in 5% BSA.

- (6)

- Secondary antibody incubation: The primary antibody was recovered, and cells were washed three times with PBS, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor™ 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:1000) at room temperature for 1 h in the dark. Cells were then washed three times with PBS.

- (7)

- Nuclear staining: Cells were stained with DAPI (1:500 in PBS) for 10 min in the dark and washed three times with PBS.

- (8)

- Mounting: Coverslips were mounted onto glass slides using an anti-fade mounting medium, avoiding air bubbles, and sealed with nail polish.

- (9)

- Imaging: Images were acquired using a laser scanning confocal microscope.

2.9. Prediction of Higher-Order Structures of MEI1 Splice Isoforms

- (1)

- Nucleotide sequences of the two MEI1 splice variants were translated into amino acid sequences using the ExPASy Translate tool (https://web.expasy.org/translate/, accessed on 24 November 2025);

- (2)

- Secondary structures were predicted using SIMPA96 (https://npsa.lyon.inserm.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page=/NPSA/npsa_simpa96.html, accessed on 24 November 2025);

- (3)

- Tertiary structures were modeled via the Phyre2 online server (http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre2, accessed on 24 November 2025).

3. Results

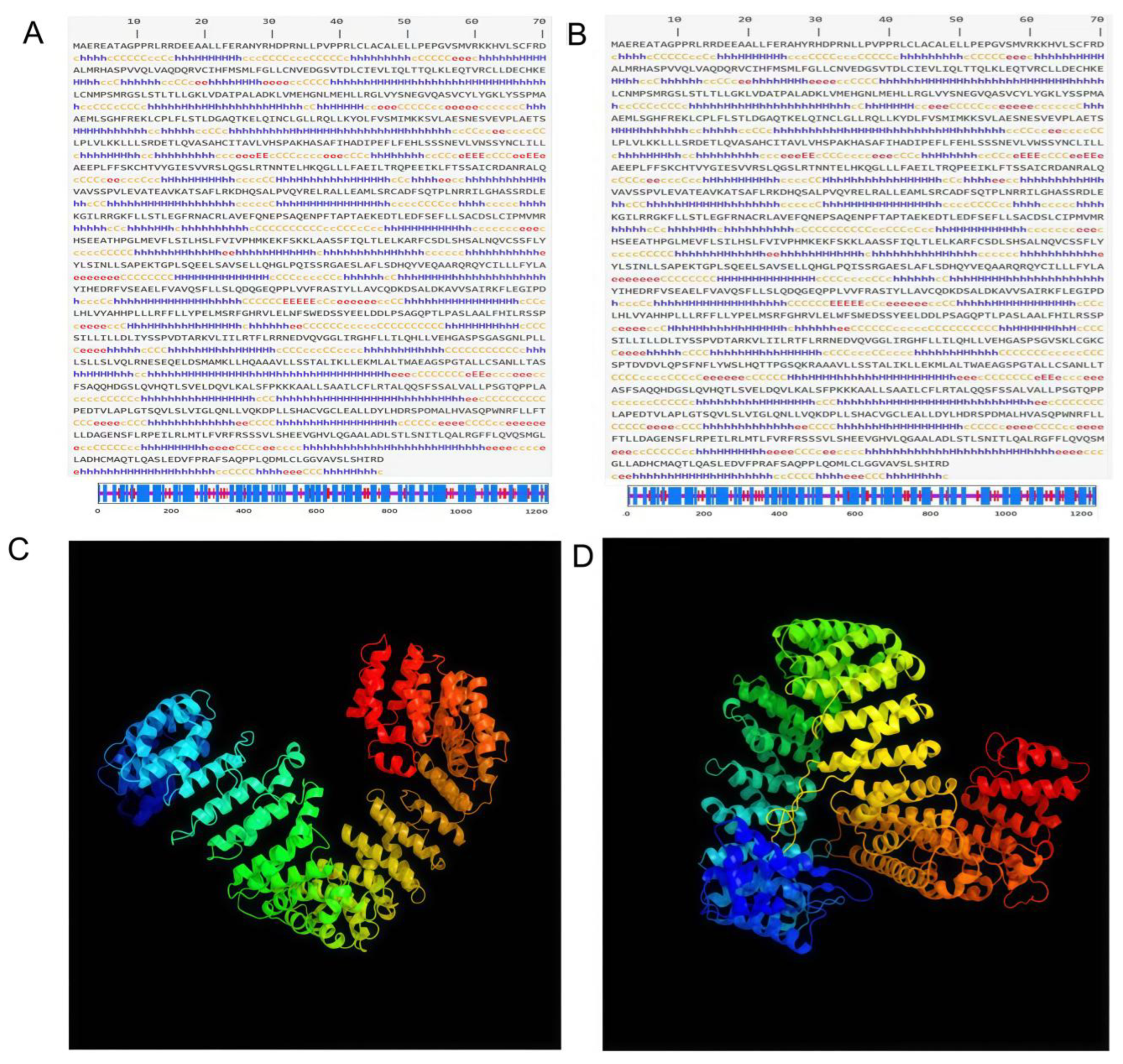

3.1. High-Order Structural Predictions for MEI1 Alternative Splicing Isoforms

3.1.1. Secondary Structure Prediction

3.1.2. Tertiary Structure Prediction

3.2. Dual Verification of MEI1 Nuclear Localization and Expression in Sertoli Cells

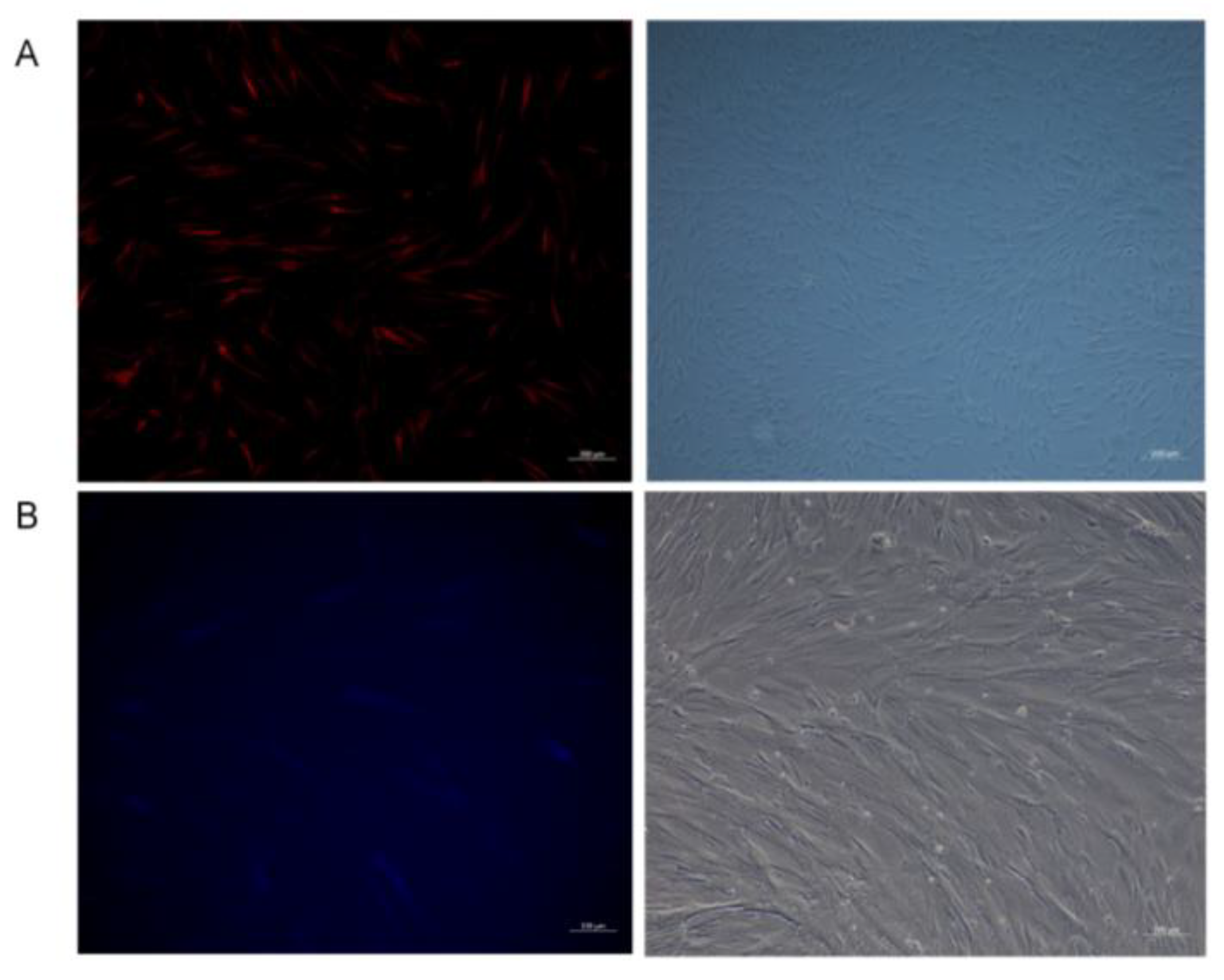

3.2.1. Construction of Two Overexpression Lentiviral Vectors, MEI1 (MXE) in pGWLV12 (Mcherry) and MEI1 (SE) in pGWLV10-BFP

3.2.2. Two Overexpression Lentiviral Vectors for Infection of Mongolian Equine Testicular Sertoli Cells

3.2.3. Localization of the MEI1 Gene in Sertoli Cells

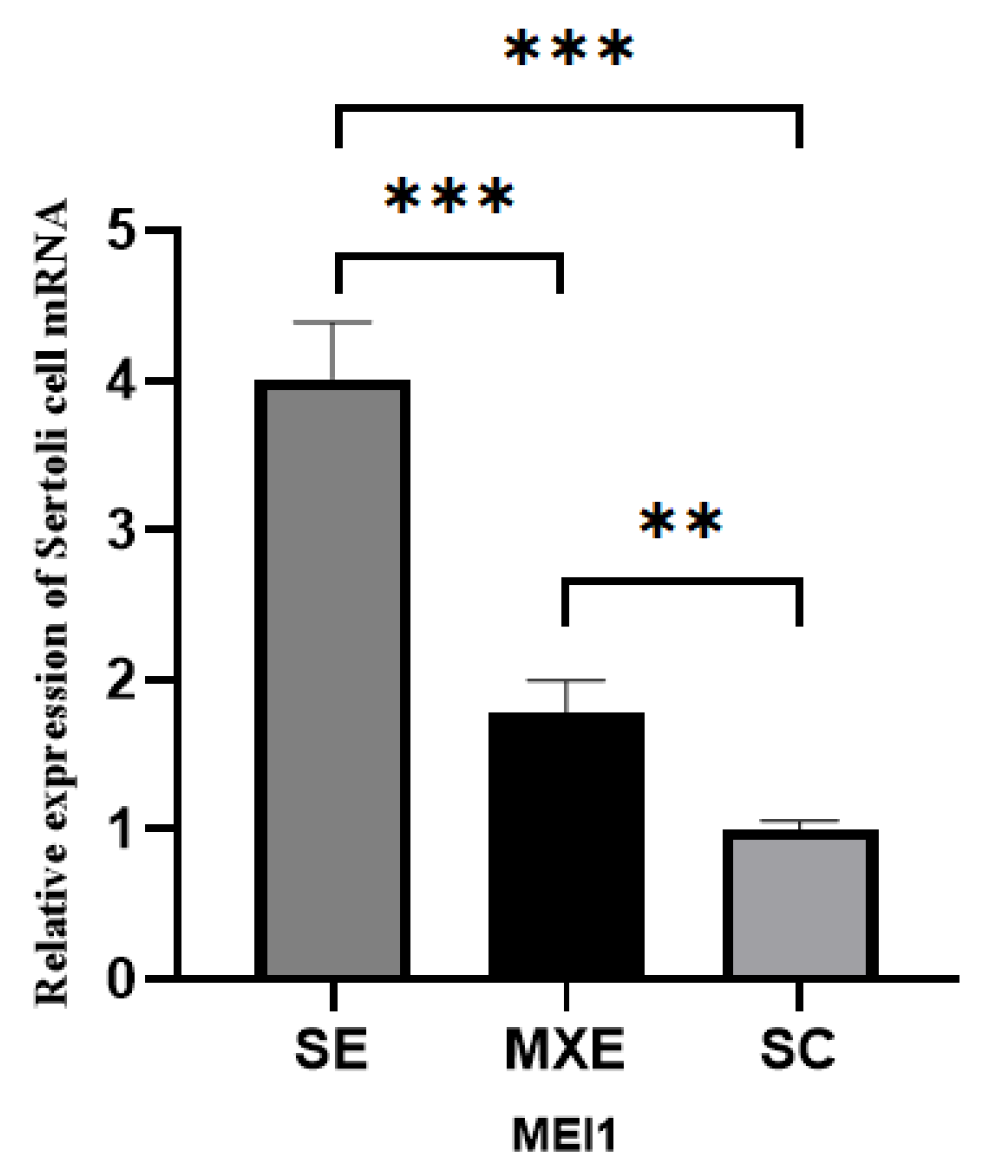

3.2.4. Detection of MEI1 Expression in the MXE and SE Groups by qRT-PCR

3.3. Divergent Roles of MEI1 SE and MXE Isoforms Revealed by Comparative Transcriptomics in Sertoli Cells

3.3.1. Results of Differential Expression Gene Screening

3.3.2. Cluster Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

3.3.3. GO Enrichment Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

3.3.4. KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

3.4. Divergent Impacts of MEI1 SE and MXE Isoforms on the Cellular Metabolome Revealed by Comparative Metabolomics

3.4.1. PCA and PLS-DA of Metabolites

3.4.2. Results of Differential Metabolites Screening

3.4.3. KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis of Differential Metabolites

3.5. Integrative Analysis of Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Data Reveals Molecular Networks Underlying MEI1 Isoform-Specific Functions

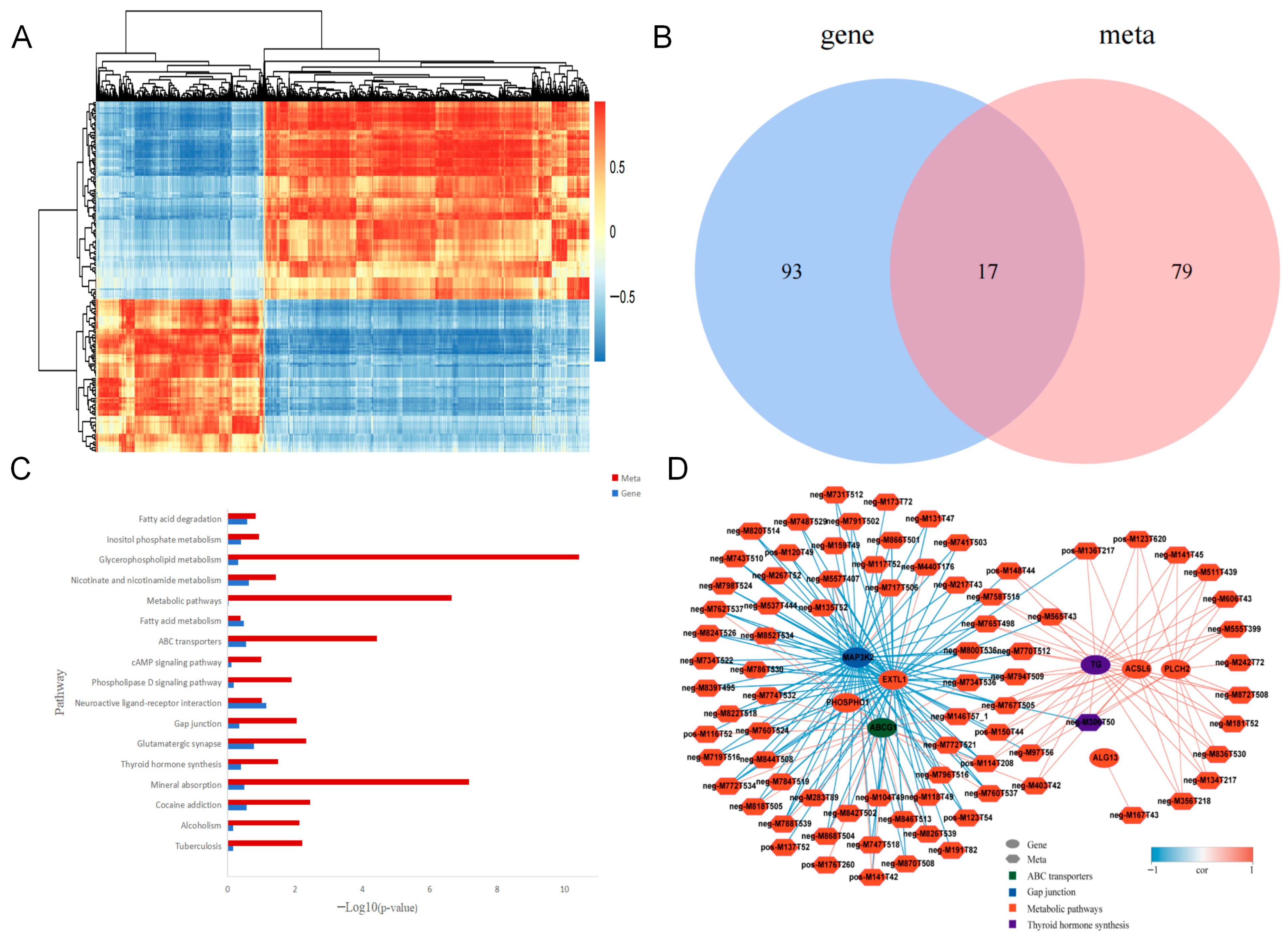

3.5.1. Correlation and Enrichment Analysis of Differential Genes and Differential Metabolites

3.5.2. Correlation Network Diagram Analysis of Differential Genes and Differential Metabolites

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mäkelä, J.A.; Hobbs, R.M. Molecular regulation of spermatogonial stem cell renewal and differentiation. Reproduction 2019, 158, R169–R187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Wu, J.; Liu, B.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, W.; Li, J.; He, Q.; He, Z. The roles and mechanisms of Leydig cells and myoid cells in regulating spermatogenesis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 2681–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Luo, Y.; Liu, M.; Huang, J.; Xu, D. Histological and transcriptome analyses of testes from Duroc and Meishan boars. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kong, L.; Liang, J.; Ma, T. Research progress on glycolipid metabolism of Sertoli cell in the development of spermatogenic cell. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2025, 54, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, W.H. Regulation of mammalian spermatogenesis by miRNAs. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 121, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eto, K.; Sonoda, Y.; Abe, S. The kinase DYRK1A regulates pre-mRNA splicing in spermatogonia and proliferation of spermatogonia and Sertoli cells by phosphorylating a spliceosomal component, SAP155, in postnatal murine testes. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2011, 355, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolcun-Filas, E.; Handel, M.A. Meiosis: The chromosomal foundation of reproduction. Biol. Reprod. 2018, 99, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Ding, J.; Li, Y.; Tian, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, W.; Lu, Z. A Novel Meiosis-Related lncRNA, Rbakdn, Contributes to Spermatogenesis by Stabilizing Ptbp2. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 752495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, N.; Keshari, S.; Shahi, P.; Maurya, P.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Gupta, K.; Talole, S.; Kumar, M. Human papillomavirus elevated genetic biomarker signature by statistical algorithm. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 9922–9932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, B.J.; Reinholdt, L.G.; Schimenti, J.C. Positional cloning and characterization of Mei1, a vertebrate-specific gene required for normal meiotic chromosome synapsis in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 15706–15711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Gao, J.; Liu, J.; Huang, X.; Zhang, H.; Ma, A.; Ye, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, G. ZFP541 maintains the repression of pre-pachytene transcriptional programs and promotes male meiosis progression. Cell Rep. 2022, 38, 110540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.M.P.; Ge, Z.J.; Reddy, R.; Fahiminiya, S.; Sauthier, P.; Bagga, R.; Sahin, F.I.; Mahadevan, S.; Osmond, M.; Breguet, M. Causative Mutations and Mechanism of Androgenetic Hydatidiform Moles. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 103, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; Miyamoto, T.; Yogev, L.; Namiki, M.; Koh, E.; Hayashi, H.; Sasaki, Y.; Ishikawa, M.; Lamb, D.J.; Matsumoto, N. Polymorphic alleles of the human MEI1 gene are associated with human azoospermia by meiotic arrest. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 51, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, B.; Tong, K.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Sun, L. Identification of the novel homozygous whole exon deletion in MEI1 underlying azoospermia and embryonic arrest in one consanguineous family. Reprod. Sci. 2025, 32, 1968–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.C.; Lee, T.W.; Mruk, T.D.; Cheng, C.Y. Regulation of Sertoli cell myotubularin (rMTM) expression by germ cells in vitro. J. Androl. 2001, 22, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.Y.; Mang, L.; Li, B.; He, X.; Du, M.; Zhao, Y.; Bai, D.; Wu, Y.Y.; Li, R.S.; Zhang, Y.Y. Regulatory effect of MEI1 gene alternative splicing events on sperm production in Mongolian horses. Acta Vet. Zootech. Sin. 2022, 53, 1096–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa-Morais, N.L.; Irimia, M.; Pan, Q.; Xiong, H.Y.; Gueroussov, S.; Lee, L.J.; Slobodeniuc, V.; Kutter, C.; Watt, S.; Colak, R.; et al. The evolutionary landscape of alternative splicing in vertebrate species. Science 2012, 338, 1587–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkin, J.; Russell, C.; Chen, P.; Burge, C.B. Evolutionary dynamics of gene and isoform regulation in Mammalian tissues. Science 2012, 338, 1593–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Burge, C.B. Splicing regulation: From a parts list of regulatory elements to an integrated splicing code. RNA 2008, 14, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W. Integrating RNA-seq and Whole-Genome Sequencing Data to Analyze the Genes and Regulatory Networks Controlling Testis Development in Hu Sheep. Ph.D. Thesis, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Y.; Liang, G.; Martin, G.B.; Guan, L.L. Functional changes in mRNA expression and alternative pre-mRNA splicing associated with the effects of nutrition on apoptosis and spermatogenesis in the adult testis. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeidi, S.; Shapouri, F.; de Iongh, R.U.; Casagranda, F.; Sutherland, J.M.; Western, P.S.; McLaughlin, E.A.; Familari, M.; Hime, G.R. Esrp1 is a marker of mouse fetal germ cells and differentially expressed during spermatogenesis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J.; Yu, T.; Lv, X.; Pan, C. Pig StAR: mRNA expression and alternative splicing in testis and Leydig cells, and association analyses with testicular morphology traits. Theriogenology 2018, 118, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Li, X.Y.; Zhang, L. Comparative Study on Testicular Morphology and Seminiferous Epithelium Cells before and after Sexual Maturation in Mongolian Horses. Heilongjiang Anim. Sci. Vet. Med. 2024, 15, 1–5+116. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; He, X.; Zhao, Y.; Bai, D.; Du, M.; Song, L.; Liu, Z.; Yin, Z.; Manglai, D. Transcriptome profiling of developing testes and spermatogenesis in the Mongolian horse. BMC Genet. 2020, 21, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.J.; Cui, Y.Y.; Zhao, Y.P.; Mang, L.; Li, B.; He, X.D.; Li, R.S.; Wu, Y.Y.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Du, M. Isolation, Culture and Identification of Testicular Sertoli Cells of Mongolian Horse in Vitro. Zhongguo Xumu Shouyi 2020, 47, 2751–2758. [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Matsuura, Y.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D672–D677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 2019, 28, 1947–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collodel, G.; Moretti, E.; Noto, D.; Iacoponi, F.; Signorini, C. Fatty Acid Profile and Metabolism Are Related to Human Sperm Parameters and Are Relevant in Idiopathic Infertility and Varicocele. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 3640450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collodel, G.; Castellini, C.; Lee, J.C.; Signorini, C. Relevance of Fatty Acids to Sperm Maturation and Quality. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 7038124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oresti, G.M.; García-López, J.; Aveldaño, M.I.; Del Mazo, J. Cell-type-specific regulation of genes involved in testicular lipid metabolism: Fatty acid-binding proteins, diacylglycerol acyltransferases, and perilipin 2. Reproduction 2013, 146, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, V.; Alvarez, L.; Balbach, M.; Strünker, T.; Hegemann, P.; Kaupp, U.B.; Wachten, D. Controlling fertilization and cAMP signaling in sperm by optogenetics. eLife 2015, 4, e05161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, A.; Martinez, M.E. Thyroid hormone action in the developing testis: Intergenerational epigenetics. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 244, R33–R46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Huan, P.; Liu, B. Expression patterns indicate that BMP2/4 and Chordin, not BMP5-8 and Gremlin, mediate dorsal-ventral patterning in the mollusk Crassostrea gigas. Dev. Genes Evol. 2017, 227, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, D.; Laiho, A.; Gyenesei, A.; Sironen, A. Identification of Reproduction-Related Gene Polymorphisms Using Whole Transcriptome Sequencing in the Large White Pig Population. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2015, 5, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beale, D.J.; Pinu, F.R.; Kouremenos, K.A.; Poojary, M.M.; Narayana, V.K.; Boughton, B.A.; Kanojia, K.; Dayalan, S.; Jones, O.A.H.; Dias, D.A. Review of recent developments in GC–MS approaches to metabolomics-based research. Metabolomics 2018, 14, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.; King, R.D.; Altmann, T.; Fiehn, O. Application of metabolomics to plant genotype discrimination using statistics and machine learning. Bioinformatics 2002, 18, S241–S248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xie, C.; Wang, K.; Takahashi, S.; Krausz, K.W.; Lu, D.; Wang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Gong, X.; Mu, X.; et al. Comprehensive analysis of transcriptomics and metabolomics to understand triptolide-induced liver injury in mice. Toxicol. Lett. 2020, 333, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Tzin, V.; Romeis, J.; Peng, Y.; Li, Y. Combined transcriptome and metabolome analyses to understand the dynamic responses of rice plants to attack by the rice stem borer Chilo suppressalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, Y.; Su, H.; Wang, D.; Li, K.; Song, Y.; Cao, G. Study of spermatogenic and Sertoli cells in the Hu sheep testes at different developmental stages. FASEB J. 2023, 37, e23084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.; Bera, A.; Eidelman, O.; Tran, M.B.; Jozwik, C.; Glasman, M.; Leighton, X.; Caohuy, H.; Pollard, H.B. A Dominant-Negative Mutant of ANXA7 Impairs Calcium Signaling and Enhances the Proliferation of Prostate Cancer Cells by Downregulating the IP3 Receptor and the PI3K/mTOR Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varma, S.; Molangiri, A.; Kona, S.R.; Ibrahim, A.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Basak, S. Fetal Exposure to Endocrine Disrupting-Bisphenol A (BPA) Alters Testicular Fatty Acid Metabolism in the Adult Offspring: Relevance to Sperm Maturation and Quality. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, W.; Zhang, J.; Lan, Z.; Deepak, R.N.V.K.; Liu, C.; Ma, Z.; Cheng, L.; Zhao, X.; Meng, X.; Wang, W.; et al. SLC22A14 is a mitochondrial riboflavin transporter required for sperm oxidative phosphorylation and male fertility. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Afrose, S.; Sawada, T.; Hamano, K.I.; Tsujii, H. Metabolism of exogenous fatty acids, fatty acid-mediated cholesterol efflux, PKA and PKC pathways in boar sperm acrosome reaction. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2009, 9, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, Y.; Aksoy, H.; Altinkaynak, K.; Aydin, H.R.; Ozkan, A. Sperm fatty acid composition in subfertile men. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2006, 75, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, L.B.; Brush, R.S.; Sullivan, M.T.; Zavy, M.T.; Agbaga, M.P.; Anderson, R.E. Decreased very long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in sperm correlates with sperm quantity and quality. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2019, 36, 1379–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Vignera, S.; Vita, R. Thyroid dysfunction and semen quality. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2018, 32, 2058738418775241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, K.J.; Reichelt, M.E.; Mustafa, S.J.; Teng, B.; Ledent, C.; Delbridge, L.M.; Hofmann, P.A.; Morrison, R.R.; Headrick, J.P. Transcriptomic Effects of Adenosine 2A Receptor Deletion in Healthy and Endotoxemic Murine Myocardium. Purinergic Signal. 2017, 13, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, H.; Ma, N.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y. Mechanisms of cAMP/PKA-Induced Meiotic Arrest in Oocytes. J. Genom. Appl. Biol. 2020, 39, 775–780. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.G.; Tao, Z.; Yang, Y.Z.; Fan, Y.Y.; Zhang, X.R.; Wu, Y.J. Research Progress on Long-Chain Acyl-CoA Synthetase (ACSL). Zhongguo Xumu Shouyi 2012, 39, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. Investigating the Role of Fatty Acid Metabolism in Non-Obstructive Azoospermia Through Multi-Omics Analysis and Experimental Validation. Master’s Thesis, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, D.; Wang, G.; Baterin, T.; Weng, Y.; Dugarjaviin, M.; Li, B. The Impact of MEI1 Alternative Splicing Events on Spermatogenesis in Mongolian Horses. Animals 2025, 15, 3435. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233435

Song D, Wang G, Baterin T, Weng Y, Dugarjaviin M, Li B. The Impact of MEI1 Alternative Splicing Events on Spermatogenesis in Mongolian Horses. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3435. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233435

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Dailing, Guoqing Wang, Terigele Baterin, Yajuan Weng, Manglai Dugarjaviin, and Bei Li. 2025. "The Impact of MEI1 Alternative Splicing Events on Spermatogenesis in Mongolian Horses" Animals 15, no. 23: 3435. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233435

APA StyleSong, D., Wang, G., Baterin, T., Weng, Y., Dugarjaviin, M., & Li, B. (2025). The Impact of MEI1 Alternative Splicing Events on Spermatogenesis in Mongolian Horses. Animals, 15(23), 3435. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233435