1. Introduction

Livestock production is a structural driver of economic growth in most low and middle-income countries. It accounts for roughly 40% of agricultural added value worldwide and still contributes about one-third of agricultural Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in sub-Saharan Africa [

1]. Beyond the farm gate, downstream segments like feed, slaughter, processing, transport, retail, veterinary and financial services employ up to 1.3 billion people, nearly one in five individuals on the planet [

2]. In West Africa’s ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States) zone, transhumance pastoralism supports employment, milk production and rangeland functions across borders, though partial protocol enforcement creates implementation challenges for cross-border disease control [

3]. Small ruminant value chains demonstrate competitive market structures with marketing efficiencies approaching 79%, indicating significant economic opportunities for productivity improvements [

4]. Livestock is therefore widely recognized as a pathway to inclusive growth, poverty reduction and resilience [

5].

However, reproductive disorders caused by infectious agents increasingly threaten both productivity and public health in small-ruminant systems. Abortive diseases such as brucellosis (

Brucella melitensis), Q fever (

Coxiella burnetii), toxoplasmosis (

Toxoplasma gondii) and chlamydiosis (

Chlamydia abortus) are major but under-diagnosed in many parts of Africa [

6]. Recent serological surveys across sub-Saharan Africa report varied seroprevalences: brucellosis 1.23–10.7% in small ruminants, Q fever up to 64.7% in aborted goats, toxoplasmosis 6.8–8.6%, and

Chlamydia abortus 2.0–7.79% [

6,

7,

8,

9]. These infections cause abortion, stillbirth, weak offspring and infertility, leading to significant economic losses to farmers and posing zoonotic risks to humans with occupational exposure resulting in human seroprevalence of 2.6% in pastoral communities [

9].

In humans, brucellosis typically presents as prolonged fever, joint pain and malaise, whereas toxoplasmosis and Q fever often result in mild, non-specific febrile illness that may be confused with other endemic infections such as malaria in diagnostic-limited settings [

10,

11]. Such misdiagnosis contributes to the underestimation of their true burden.

The resulting economic burden is considerable. Correctly diagnosed brucellosis treatment ranges from € 9 per patient in Tanzania to € 650 in Algeria [

12]. Beyond direct medical costs, socio-economic impacts include reduced offspring production, decreased milk yields, and compromised sales revenues, disproportionately affecting smallholder livelihoods [

13].

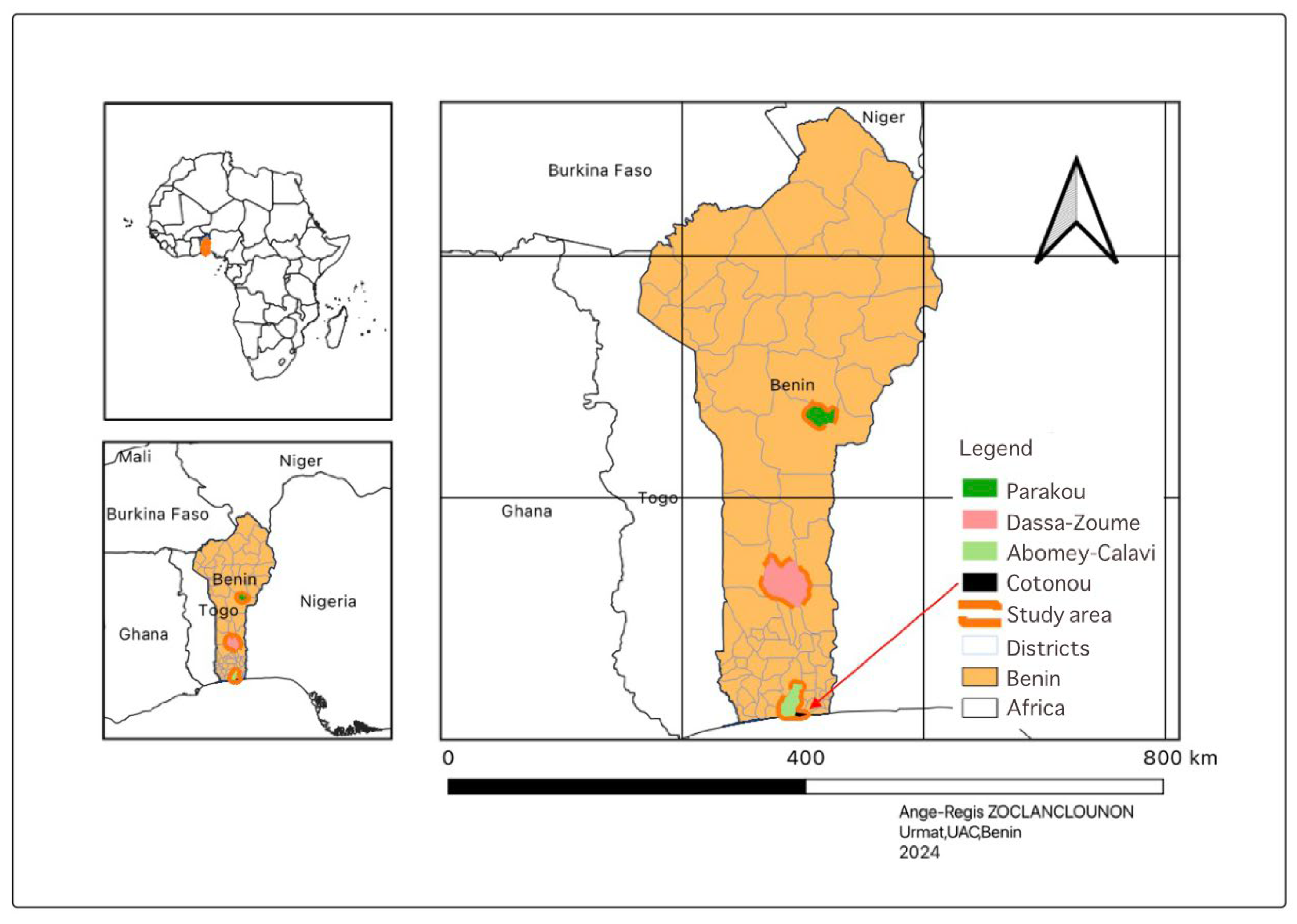

In Benin, livestock contributes 5.7% of national GDP and 14.9% of agricultural GDP; annual meat production exceeds 70,000 t [

14]. Small ruminants represent about 60% of the national herd and provide over 12% of total dietary protein [

14]. They support the livelihoods of more than 500,000 households as an equally large population at risk of neglected zoonoses [

14]. Recent market analyses revealed that the purchase price of kid or lamb in Benin for breeding varied from 5000 XOF (8.13 dollars USD) to 10,000 XOF (16.26 dollars USD), depending on the location [

4]. Benin’s first documented seroprevalence study of

Chlamydia abortus in small ruminants found seropositivity rates of 7.79% and 6.49% in two southern poles, confirming enzootic ovine abortion as a local animal health and public health concern [

8].

Risk factors for these diseases include poor hygiene during parturition, communal grazing, mixed-species husbandry and limited access to veterinary services [

9]. Field studies identified specific risk determinants including history of abortion, parity, species mixing in herds, assisting births with bare hands, handling placental membranes without protection, transhumance movements, and informal slaughter practices [

6,

9,

15]. However, local evidence on how these management conditions interact with human behavior and perception to influence disease persistence is still lacking.

To date, no study in Benin has examined how different professional groups within the small-ruminant value chain (farmers, butchers, meat inspectors, and para-veterinary agents) understand and respond to abortion-causing zoonoses. Existing studies in the region have largely focused on seroprevalence or clinical diagnosis, with limited attention to behavioral or awareness-related determinants. Recent knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) studies across Africa reveal critical gaps: in Cameroon, small ruminant farmers had very low mean knowledge scores (0.10 ± 0.20) and risk-perception scores (0.12 ± 0.33) regarding abortive zoonoses [

16]; in Zimbabwe, only 34% of farmers could correctly identify abortion causes and specific pathogen awareness was low (10% for

Brucella, 6% for

C. abortus, 4% for

T. gondii) [

6]; in Ethiopia, 54.2% of respondents handled placentas and aborted fetuses with bare hands, and only 5.8% achieved good knowledge scores [

15]. These studies consistently document weak translation of knowledge into safer practices, with attitudes and practices often misaligned with knowledge levels [

17]. This represents a critical knowledge gap, as effective prevention and reporting depend on the attitudes and practices of those in daily contact with animals and their products.

To address this gap, we conducted a cross-sectional study to document farmers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices related to abortion-causing zoonoses, and to identify management behaviors that may contribute to their persistence.

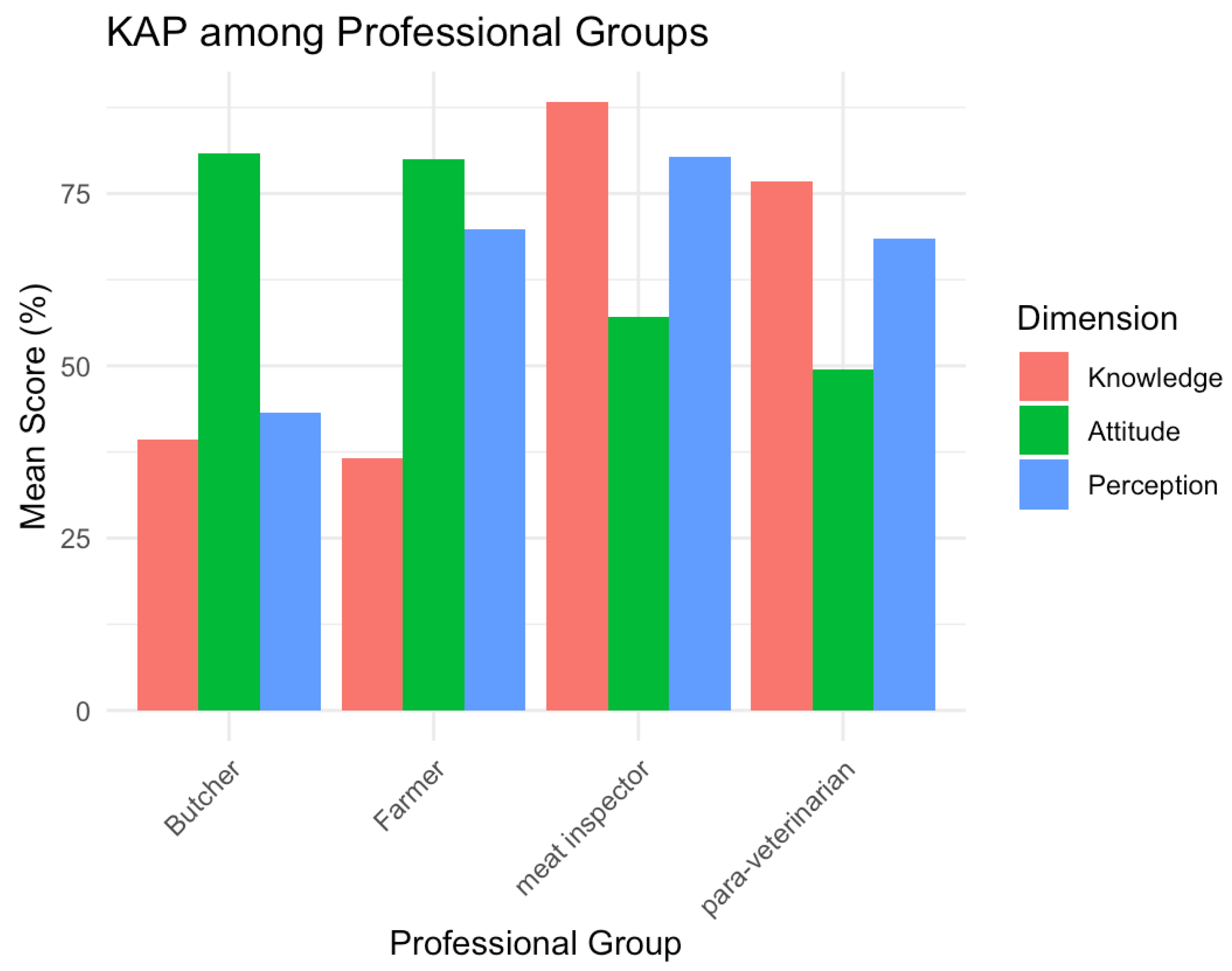

We hypothesized that (i) Knowledge, Attitudes and Perception (KAP) levels would vary significantly between professional groups, (ii) higher knowledge would be associated with more desirable attitudes toward biosecurity and hygiene, and (iii) socio-demographic and occupational factors would influence perception of zoonotic risk.

The study aimed to provide behavioral evidence needed to design feasible hygiene-based interventions targeting brucellosis and related pathogens in Benin’s small-ruminant sector.

4. Discussion

This study documented critical gaps in knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions regarding abortive zoonoses among four professional groups within Benin’s small-ruminant value chain. Our findings reveal low pathogen-specific awareness, persistent risky practices, and weak translation of knowledge into protective behaviors. These patterns reflect broader structural constraints in veterinary service delivery, gendered information flows, and economic incentives that shape livestock disease management across West Africa.

4.1. Knowledge Gaps and Their Structural Determinants

Producers, butchers, meat inspectors, and para-veterinarians showed limited knowledge of abortive pathogens, particularly regarding clinical signs (K6) and zoonotic transmission routes. Only one-fifth of respondents recognized placental contact as hazardous, and more than two-thirds disposed of aborted material bare-handed. Similar deficits have been documented across sub-Saharan Africa. In Kenya, only 12% of farmers understood animal-to-human transmission pathways [

23]. In Zimbabwe, specific awareness of

Brucella (10%),

C. abortus (6%), and

T. gondii (4%) was equally low despite 44% reporting recent reproductive problems [

6]. In Ethiopia, 54.2% of respondents handled placentas with bare hands, and only 5.8% achieved good knowledge scores [

15].

These persistent gaps are not simply individual ignorance but reflect systemic determinants. Limited veterinary surveillance and diagnostic capacity reduce awareness and control prioritization at national levels across West Africa [

24]. Educational attainment strongly predicts safer practices; in Tanzania, farmers with tertiary education were significantly less likely to self-administer antimicrobials (76.6% of respondents reported self-treatment). In north-west Côte d’Ivoire, veterinary messaging predominantly targeted men, leaving women who perform most dairy processing with lower access to prevention information despite their higher exposure risk [

25]. Economic constraints also shape behavior. A six-country West African study (n = 728 peri-urban dairy farms) found marked heterogeneity in commercialization levels, which affected farmers’ willingness to adopt vaccination and biosecurity measures [

26].

Our regression analyses confirmed these patterns. Knowledge scores were significantly higher among meat inspectors and para-veterinarians, reflecting formal training advantages. Urban and multi-site workers also scored better, likely due to greater exposure to veterinary services and information networks. Respondents who had directly experienced abortions showed higher knowledge, suggesting that experiential learning occurs but only after economic losses.

4.2. Abortion Patterns and Endemic Transmission

Abortions occurred year-round rather than seasonally in our study communes. This pattern suggests endemic transmission driven by persistent management failures rather than climatic peaks. It contrasts with rainfall-linked seasonality observed in Senegal [

27] and implies that continuous circulation of

Brucella and allied pathogens requires non-seasonal, sustained interventions. Year-round occurrence also reflects the absence of synchronized breeding or calving management in Benin’s extensive small-ruminant systems.

Transhumance and livestock mobility amplify transmission risk. In Mali, individual

Brucella seroprevalence reached 8.2% (herd-level 21.2%), with mobility status and abortion history significantly associated with infection [

28]. Benin’s cross-border pastoral movements and communal grazing practices likely sustain similar transmission dynamics, though our study did not collect mobility data. Integrating market and border testing into surveillance systems has been recommended to address mobile herd risks [

28].

4.3. Occupational Exposure and Under-Recognition of Human Cases

Butchers and para-veterinarians reported the highest prevalence of self-reported “brucellosis-like symptoms” (prolonged fever, joint pain). However, this finding must be interpreted cautiously, our study did not collect laboratory confirmation, and symptom overlap with malaria and other febrile illnesses. In a Nigerian study only 10% of respondents had ever suspected brucellosis, far below the 30% attribution rate for unexplained fevers found in Nigeria [

29]. This under-recognition likely stems from weak clinical awareness, limited laboratory access, and the non-specific nature of brucellosis presentation. Occupational seroprevalence studies in pastoral communities have documented human seropositivity rates of 2.6% [

9], confirming zoonotic transmission but highlighting the need for integrated human–animal surveillance to capture true burden.

4.4. Knowledge-Attitude-Perception Relationships

Our correlation analyses revealed a moderate inverse relationship between knowledge and risky attitudes. This suggests that better information fosters safer behavior, consistent with findings from Saudi Arabia and Bangladesh where formal training improved KAP metrics [

30,

31]. However, knowledge was not significantly linked to risk perception, and attitude was unrelated to perception. This dissociation indicates that factual awareness alone does not translate into a sense of personal vulnerability.

These findings underscore the need for risk communication strategies that go beyond information transfer. Behavioral interventions combining practical demonstrations, visual aids, and participatory learning have been implemented in African dairy and pastoral settings [

26].

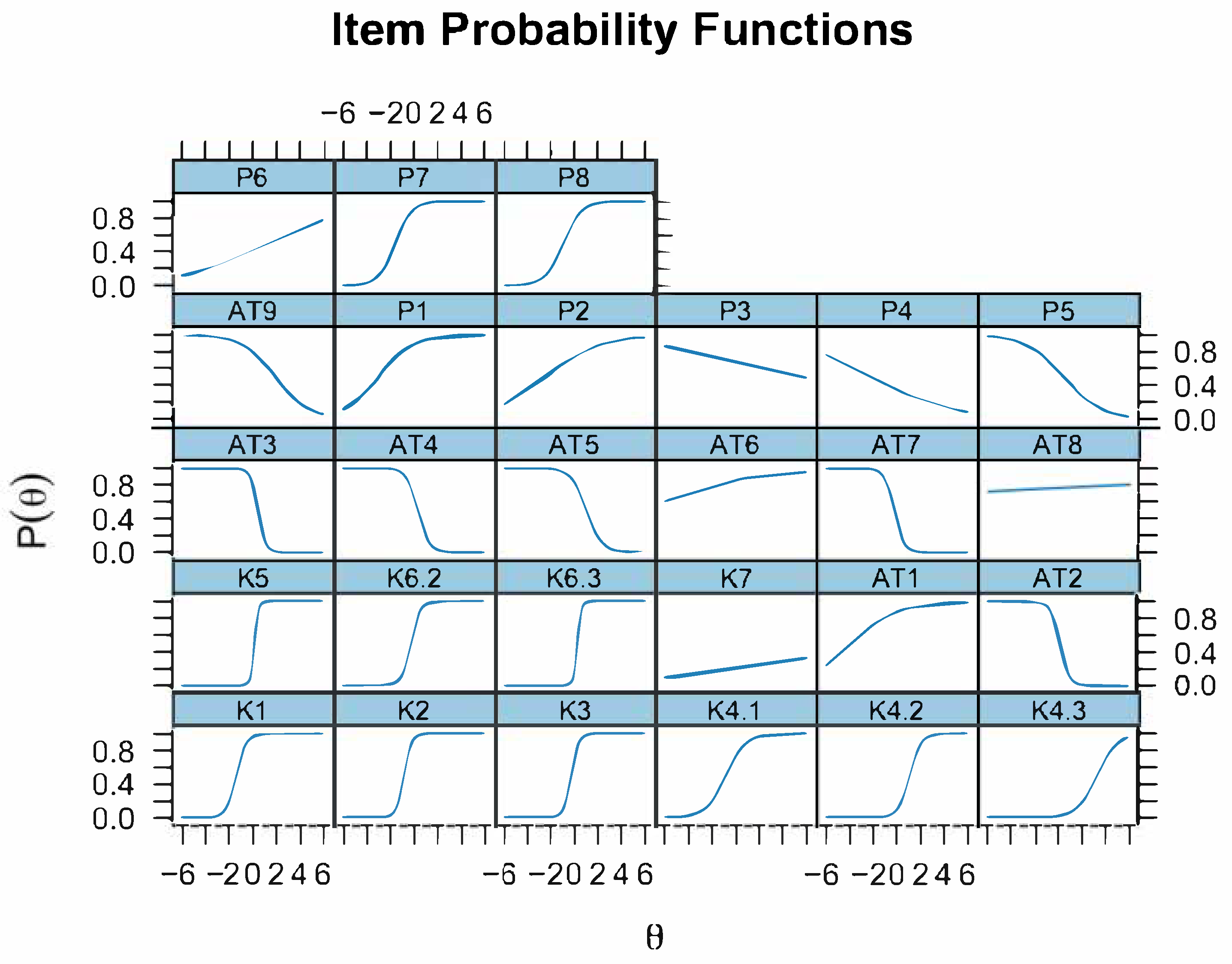

4.5. Psychometric Performance and Scale Validation

Our IRT analyses provided nuanced insights into item performance. The Knowledge sub-scale demonstrated strong psychometric properties after refinement. Eight retained items displayed high mean discrimination and difficulties ranging from −1.1 to 2.0. “Name at least three abortive diseases” (K4.3) was the best performer, effectively separating well-informed respondents. Conversely, basic items like “animal-to-human transmission” (K1) were easy but still discriminated adequately.

The Perception sub-scale showed moderate discrimination and clearly negative difficulties, indicating that most participants readily recognized the severity of abortive diseases. Items on danger to animals or humans (P1, P2) were almost always endorsed creating a ceiling effect. The most informative perception item was “I already take enough precautions”.

The Attitude sub-scale posed greater challenges. Several items exhibited negative discrimination values, suggesting misinterpretation, poor wording, or reverse-coding issues. After filtering, only one attitude item remained useful, and it discriminated poorly despite extreme ease. This ceiling effect virtually all respondents claimed they protected themselves when handling aborted fetuses likely reflects social desirability bias, a common limitation in self-reported KAP data [

32,

33].

Bootstrap resampling confirmed considerable variability in parameter estimates. Items K5 and K6.3 displayed very high discrimination but wide confidence intervals, indicating instability due to our modest sample size (n < 200). This instability is not uncommon in small-sample IRT applications and underscores the value of non-parametric resampling to characterize uncertainty [

34].

Internal consistency varied across sub-scales and the perception fell below the conventional 0.70 threshold. Lower alpha can occur in multidimensional constructs or short scales and does not necessarily invalidate the measure [

35]. Recent KAP validation studies have accepted α ≈ 0.6 for newly developed scales, particularly when complemented by item-total correlations and IRT fit indices [

36,

37]. Our iterative approach combining 2-PL IRT, Cronbach’s α, and expert review aligns with best practices documented in leptospirosis, chronic kidney disease, and confined-space KAP validations [

34,

35,

37].

4.6. One Health Policy Implications

Brucellosis and other abortive agents (

Coxiella burnetii, Chlamydia abortus, Toxoplasma gondii) require integrated animal–human strategies. West African policy frameworks increasingly emphasize One Health approaches, but implementation gaps persist. Laboratory and diagnostic services remain constrained, limiting confirmation of zoonotic infections and undermining surveillance [

24].

Our results suggest two priority interventions for Benin. First, scale up flock vaccination using context-appropriate delivery models. A six-country West/Central African study proposed public–private partnership (PPP) models tailored to local commercialization levels, arguing that transactional delivery (the most common current model) is suboptimal in many settings [

26]. Sustained vaccination has markedly reduced bovine and human brucellosis, where implemented and should be combined with supervised disposal of fetal products (P5 item) to address the high frequency of unprotected handling (AT9 item).

Second, deliver context-specific training that combines practical demonstrations with visual aids, targeting farmers and butchers who lack formal biosafety instruction. Training should be gender-sensitive, ensuring women involved in dairy processing and flock management receive tailored messages [

25]. Integrating market and border testing for transhumant herds can address mobility-related risks [

28]. Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Programs (FELTP) that include veterinary epidemiology have strengthened outbreak detection and One Health responses in Nigeria and represent scalable capacity investments [

38].