Simple Summary

In the present study, reference intervals for hematological ratios in dogs were established. Hematological inflammatory ratios, such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte (NLR), monocyte-to-lymphocyte (MLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte (PLR), and systemic inflammatory index (SII), are widely used because they are easily calculated from a complete blood count and involve no additional cost. Hematological ratios have recently demonstrated prognostic value in acute inflammatory diseases, neoplastic conditions, hepatic and gastrointestinal pathologies, as well as acting as biomarkers for the early detection of tumors and cardiorespiratory diseases. The following reference intervals were established: 1.3–7.1 for NLR; 0.1–0.3 for MLR; 40.4–271.1 for PLR, and 224.6–2191.7 for SII. This may represent a useful tool in clinical practice, enabling rapid comparison and supporting clinicians in prognostic assessment of certain diseases, as well as potentially serving as a predictive biomarker.

Abstract

Hematological inflammatory ratios such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte (NLR), monocyte-to-lymphocyte (MLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte (PLR), and systemic inflammatory index (SII) have recently demonstrated prognostic value in acute inflammatory diseases, neoplastic conditions, hepatic and gastrointestinal pathologies, as well as acting as biomarkers for the early detection of tumors and cardiorespiratory diseases. In addition, they can be easily calculated and have no additional cost. The purpose of this study was to establish reference ranges for these ratios in the canine population, thereby providing support for clinical practice. Data was collected from previous studies. The dogs included in the study had to have anamnesis and physical examination without abnormalities and within reference limits in laboratory results. A total of 156 samples were included and divided by sex and age. The following reference intervals were established: 1.3–7.1 for NLR; 0.1–0.3 for MLR; 40.4–271.1 for PLR, and 224.6–2191.7 for SII. Statistical significant difference was found between sexes and NLR, with males showing a higher ratio than females. Regarding age, statistical significance was found between juveniles and senior dogs for NLR. PLR and SII showed higher ratios in senior dogs compared to adults and juveniles. This study may serve as a guide in clinical practice for the interpretation of hematological inflammatory ratios.

1. Introduction

The use of novel biomarkers as an available tool in small animal practice has increased in recent years in veterinary medicine [1]. Depending on their use, biomarkers can be categorized as risk, diagnostic, monitoring, predictive, prognostic, response, or safety biomarkers [2].

Hematological biomarker ratios such as neutrophil-to-lymphocyte (NLR), monocyte-to-lymphocyte (MLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte (PLR) can be easily obtained by performing a complete blood count (CBC) and have been used to determine prognosis in acute inflammatory diseases such as peritonitis, pancreatitis or acute diarrhea [3,4,5,6,7,8], neoplastic conditions [9,10,11,12], and cardiovascular, intestinal or hepatic pathologies [13,14,15,16,17,18]. These hematological ratios have proven to be more effective than individual hematological parameters in assessing some systemic responses [4,5,6].

In one study, dogs with systemic inflammatory response syndrome and septicemia showed a lower NLR compared to the non-septic dogs [4]. In dogs with chronic enteropathies, NLR has been useful to subclassify the origin of the enteropathy and has also been useful as an inflammatory marker [17,18]. Furthermore, it can also be used as a predictive marker, as in another study, NLR was higher in dogs affected by a portosystemic shunt that required more than one intervention [14]. NLR also has a prognostic value in mammary tumors, where higher ratios are related to a lower survival rate [12]. In dogs affected by soft tissue sarcoma, NLR appears to be higher than in dogs with benign soft tissue tumors [19]. NLR has also been found significantly higher in dogs with oropharyngeal tumors compared to dogs with periodontitis or healthy dogs [20]. In one study comparing healthy and sick seropositive dogs infected by Leishmania infantum, NLR was higher in moderate to severe stages of the disease compared to the healthy seropositive and seronegative dogs. Additionally, in this study, MLR values were higher in seropositive dogs with hypoalbuminemia [21]. In dogs with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, lower MLR was found to be a useful predictor of shorter time-to-progression and survival [11]. In another study conducted by Marchesi et al. on dogs with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), an MRL above the reference range is highly indicative of the disease [22]. In dogs with primary immune-mediated hemolytic anemia, a low MLR in combination with a high NLR was associated with a poorer prognosis [23].

In a study involving puppies affected by parvovirosis, PLR was higher in non-survivors [5]. Similarly, in dogs with acute pancreatitis, this ratio was higher than in the control group and linked to a longer recovery [6]. In dogs with chronic enteropathy, PLR could be considered a potential marker of treatment efficacy [24]. Also, this marker decreases during treatment time [13]. In addition, PLR could be used as a screening tool for malignancy in nasal tumors [25].

The systemic inflammation index (SII), which can be calculated by multiplying the total neutrophil count by the total platelet count and dividing by the total lymphocyte count, has been widely used in human medicine mostly as a biomarker predictor for certain tumors as well as respiratory and cardiovascular disease [26,27,28,29]. In veterinary medicine, few studies have evaluated its potential use as a novel inflammation marker of prognosis in inflammatory or neoplastic diseases [13,30]. In one study, dogs that survived leptospirosis infection showed higher SII values than healthy dogs or dogs that died from the disease [31]. In dogs with leishmaniosis, SII tended to increase as the disease worsened [32]. Dogs with a high body condition score also had higher SII values [33].

To the author’s knowledge, there is no information regarding hematological ratios reference intervals in a large population of dogs, although its use has been proven to be more effective than the use of individual indicators. The aims of this study were to establish reference intervals for the NLR, MLR, PLR, and SII in a large population of dogs, and to determine if there were significant differences between age groups or sexes.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective observational study, using samples collected from twenty-three veterinary centers, including first opinion veterinary clinics and reference veterinary hospitals, between 2018 and 2024. The study was conducted in the Mediterranean area of Spain, including outdoor and indoor dogs; data such as age or sex were included randomly. Preventive care information, such as deworming or vaccination, was not available for all patients and, therefore, was not included in the study. To be included in the study, dogs had to have anamnesis and physical examination without abnormalities and obtain laboratory results within reference limits, including negative Leishmania infantum antibodies titers. Physiological or subclinical age-related changes, such as periodontitis conditions or joint degeneration, were not considered diseases in dogs over 8 years of age.

Data were collected from previous studies by the same investigation group, and the examined sample was divided into two groups by age range (juvenile from 0 to 1 years old; adult from 1 to 8 years old; senior from 8 years onwards) and by sex (males and females).

All samples were processed by the same reference laboratory. The analysis included a complete blood count (CBC; Celltac Alpha VET MEK-6550; Nihon Khoden, Rosbach, Germany) with blood smear evaluation (Figure S1). Biochemical analytes measured included creatinine, urea, alanine aminotransferase, and total serum proteins (CS 300 analyzer; Dirui, Jilin, China). Serum electrophoretograms were run by CE (Minicap instrument; Sebia, Lisses, France). Serum of all animals was also tested for antibodies to Leishmania infantum by an immunofluorescent antibody test (IFAT) (Axio Scope HBO 50 microscope; Zeiss, Madrid, Spain) because this infectious agent is highly prevalent in the study area.

Hematological ratios were calculated by dividing the total neutrophil count, the total monocyte count, and the total platelet count by the total lymphocyte count. The units reported by the reference laboratory for all white blood cells (WBCs) and platelets were the same (K/µL). Dogs with platelet aggregates were detected by the blood smear and excluded from the PLR and SII. SII was calculated by multiplying the total neutrophil count by the total platelet count and dividing by the total lymphocyte count.

Outliers of each hematological value were identified using the Reference Value Advisor macro (v. 2.0; Redmon, WA, USA). Histograms of each hematological ratio were assessed to identify potential outliers. Tukey interquartile fences and the Dixon outlier range statistic were used to identify true and suspected outliers. True outliers were deleted, whereas suspected outliers were retained following the American Society for Veterinary Clinical Pathology (ASVCP) guidelines [34]. RIs were obtained (Reference value advisor v.2.0; Microsoft) through the nonparametric method, given that the population size was large enough (>120). Information regarding data distribution was not necessary because nonparametric methods were used. Moreover, 95% RIs were calculated with 90% confidence intervals (CIs) for reference limits according to the ASVCP 2012 guidelines.

Statistical analysis for each subgroup was performed using R version 4.4.1 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used for each group to test the hypothesis of normality. Outliers were detected by box-plot and eliminated if considered aberrant observations. Since the data did not follow a normal distribution, the Mann–Whitney U test was used to establish differences between the two groups. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare more than two independent groups. A post hoc analysis of statistically significant associations was conducted using Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction. Results were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05. The plots were created using Matplotlib version 3.8.0 software (Matplotlib Development Team, Austin, TX, USA).

3. Results

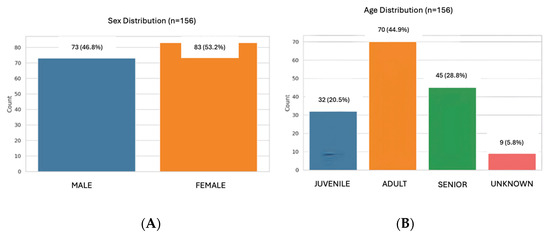

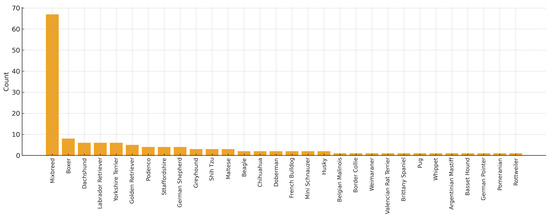

The study population included 156 samples from healthy dogs, 73 males (46.8%) and 83 females (53.2%). A total of 32 dogs aged 0 months to 1 year (20.5%), 70 dogs aged 1 to 8 years (44.9%), and 45 dogs older than 8 years were included (28.8%) (Figure 1). Several breeds were included: Boxer (n = 8), Labrador Retriever (n = 6), Dachshund (n = 6), Yorkshire Terrier (n = 6), Golden Retriever (n = 5), Podenco (n = 4), Sttaffordshire Bull Terrier (n = 4), German Sheperd (n = 4), Greyhound (n = 3), Shih Tzu (n = 3), Maltese (n = 3), Beagle (n = 2), French Bulldog (n = 2), Chihuahua (n = 2), Doberman (n = 2), Mini Schnauzer (n = 2), Siberian Husky (n = 2), Belgian Malinois (n = 1), Boder Collie (n = 1), Valencian Terrier (n = 1), Brittany Spaniel (n = 1), Pug (n = 1), Whippet (n = 1), Weimaraner (n = 1), Argentinian Mastiff (n = 1), Basset Hound (n = 1), Pointer (n = 1), Pomeranian (n = 1), Rottweiler (n = 1). A total of 67 dogs were mix breed. In 13 dogs, the breed was not registered (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Distribution of the population by sex (A) and age (B).

Figure 2.

Description of the population according to breed included in the study.

PLR and SII were calculated based on a 124 population, as platelet aggregates were found on 32 blood smears and excluded from these parameters.

From the PLR and SII, 1 outlier was found to be aberrant and deleted.

RIs were obtained for the different ratios as follows: 1.3–7.1 for NLR; 0.1–0.3 for MLR; 40.4–271.1 for PLR, and 224.6–2191.7 for SII (Table 1).

Table 1.

Reference intervals for hematological inflammatory ratios in healthy dogs.

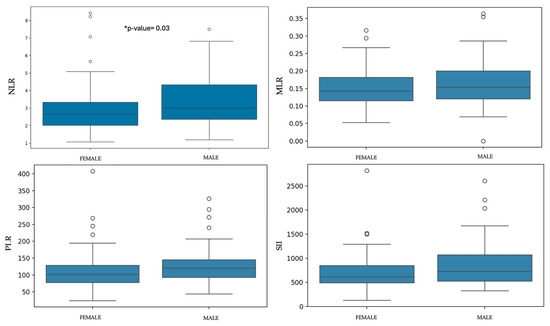

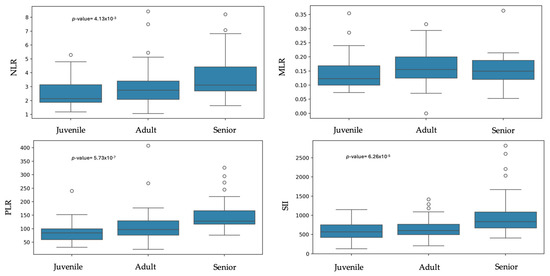

Statistically significant difference were found between sexes and NLR, with males showing a higher ratio than females (p-value = 0.03). No significant differences were observed between males and females for MLR, PLR, and SII (Table 2 and Figure 3). Regarding age, statistically significant differences were found between juveniles and senior dogs for NLR (p-value = 4.13 × 10−3). PLR and SII values were significantly higher in senior dogs compared to adult and juvenile dogs (PLR: p-value = 5.73 × 10−7; SII: p-value = 6.26 × 10−5). MLR showed no statistical differences between groups (Table 3 and Figure 4).

Table 2.

Comparison of the different inflammatory ratios between females and males.

Figure 3.

Box-plots of each ratio comparing females and males. * Statistically significant differences were observed with higher values in males than in females.

Table 3.

Age-related comparison of hematological inflammatory ratios.

Figure 4.

Box plots of the inflammatory ratios across age groups.

4. Discussion

This study establishes hematological ratios with a high confidence level in a large population of healthy dogs.

Generally, most studies conducted to date have compared a population of sick dogs with relatively small samples of healthy controls. The largest sample size study compares the NLR in dogs with inflammatory bowel disease with 150 healthy dogs, in which the NLR in healthy dogs showed a range between 1.1 and 13.3 [18]. The upper reference limit in our study is lower (7.1); this difference could be due to the age or breed of the dogs included in the study, since previous studies have confirmed variations in these parameters, such as a lower lymphocyte count or a high neutrophil count in older dogs [35]. The type of analyzer used in this study is not specified, which could potentially contribute to differences between studies. In another study, RI for NLR in a group of 44 healthy dogs ranged from 1.0 to 4.1, but it was also correlated with age, with no further specifications of the dogs included. In the present study, 45 dogs were older than 8 years, which could be associated with the observed increase in the upper limit of the reference range [17]. In addition, an age-related increase in neutrophils is commonly observed [36,37]. NLR has been found significantly higher in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease, mammary tumors, leishmaniosis, and oral tumors [12,20,21,38].

The RI for MLR in this study was 0.1 to 0.3, consistent with other studies using a small number of dogs as a control population. These studies also showed statistically significant differences between healthy dogs and dogs with severe myxomatous valve disease, leishmaniosis, or inflammatory bowel disease [21,22,38,39]. These results may be attributable to the monocytosis and lymphopenia secondary to inflammation, although it should be taken into account that stress situations could cause these alterations [18,40].

The RI for PLR was 40.4 to 271.1, this result is consistent with the control groups of other studies [21,31,39], however they differ from the findings of a study in dogs where values higher than 131.6 were used as a predictor of IBD, although in this study blood smears were not examined, raising the possibility that the platelet count was actually higher due to the presence platelet aggregates and therefore the PLR would also be higher [22]. Another study conducted in dogs reported that PLR higher than 285 could be consistent with hypercortisolism; these results are in agreement with our results, as the PLR cutoff associated with hypercortisolism (>285) is higher than the upper reference limit established in our population [41].

SII is significantly higher in studies conducted in dogs with obesity, leishmaniasis, enteropathies, diabetes mellitus, and vector-borne diseases [13,31,33,42,43]. In the present study, the RI was 224.6–2191.7. This reference range is wider than that reported in another study (52.93–1503) with a control population of 20 dogs, which may be attributable to the smaller control population or to other factors such as body condition, since it has been shown to increase this index [33], and was not a variable considered in the present study; or the age of the dogs included in the study as it is a factor that could lead to changes in the CBC [35,37].

Significant differences were found between males and females in this study for the NLR. This finding is consistent with previous studies in both humans and dogs, which reported higher absolute neutrophil counts in males compared to females [35,44,45]. This difference may be explained by the influence of sex hormones in intact males, as androgens might promote the myeloid lineage cells [35]; however, reproductive status was not considered in the present study.

Age was identified as a statistically significant factor for NLR, with lower values in dogs from 0 to 1 year old than in seniors, and for PLR and SII, which were significantly higher in seniors compared with adults and juveniles. This could be because neutrophils increase in adulthood, probably as a result of physiological or subclinical age-related changes, such as periodontal disease or joint degeneration, and by the decline in lymphocytes resulting from a reduced immune response [35,36,37]. Platelet count also has a positive correlation with aging [35,37,46], probably due to inflammation or thrombocytosis secondary to an epinephrine response [35,36]. These data will be relevant for the individualization of ratios in diseased patients, taking into account both sex and age.

Limitations of this study are that certain variables, potentially having a significant impact on certain results, such as reproductive status and body condition, were not considered. In addition, age-related conditions such as periodontitis and joint degeneration were not considered as a disease in the group of dogs over 8 years of age, which could have influenced some of the hematological parameters. Another limitation of the study, given that the patients were obtained from previous studies, is the lack of standardization in the information collected and physical examination, data that could potentially have affected the results. Furthermore, to rule out any subclinical disease, other tests such as urinalysis, coprological, or other serological tests could have been performed. However, despite the increasing study of these hematological ratios in veterinary medicine as both diagnostic and prognostic markers, this is the first study to present reference ranges in a large population of dogs, including differences between males and females and across different age groups, which may be of great clinical relevance for certain pathologies. Future lines of investigation could include prospective studies with a better-defined population and standardized clinical evaluations, including parameters such as body condition, vaccination and deworming status, reproductive status, and age-related conditions.

5. Conclusions

Reference intervals for NLR, MLR, PLR, and SII can be used as a guide in clinical practice to help in the diagnosis, monitoring, and prognosis of inflammatory or neoplastic diseases in canine patients, providing clinicians with accessible, cost-free, and clinically relevant biomarkers derived from a routine complete blood count. This study also reveals the importance of taking individual factors such as age or gender into account when evaluating these parameters to avoid misinterpretation and to improve diagnostic accuracy. These reference intervals represent a meaningful step forward for integrating hematological inflammatory ratios into everyday clinical decision-making, supporting early detection, disease monitoring, and prognostic assessment across a wide range of conditions. Future research should build on this foundation by evaluating these ratios in specific pathological contexts and disease severities, with the goal of refining their use as reliable, evidence-based biomarkers in veterinary medicine.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ani15233376/s1, Figure S1. Complete analysis with reference values.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.F.N. and L.G.-V.; methodology, P.F.N.; software, P.F.N.; validation, P.F.N., L.G.-V. and M.M.; formal analysis, P.F.N.; investigation, P.F.N.; resources, P.F.N. and M.M.; data curation, P.F.N.; writing—original draft preparation, P.F.N.; writing—review and editing, P.F.N. and L.G.-V.; visualization, P.F.N., L.G.-V. and M.M.; supervision, P.F.N. and L.G.-V.; project administration, P.F.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study since the data was obtained from the database of previous studies.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the owner of the animals involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the laboratory for its collaboration in the processing of the samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NRL | Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| MRL | Monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| PLR | Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| SII | Systemic inflammatory index |

References

- Tharangani, R.W.P.; Skerrett-Byrne, D.A.; Gibb, Z.; Nixon, B.; Swegen, A. The Future of Biomarkers in Veterinary Medicine: Emerging Approaches and Associated Challenges. Animals 2022, 12, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, M.J.; Smith, E.R.; Turfle, P.G. Biomarkers in Veterinary Medicine. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2017, 5, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, N.; Llewellyn, E.A.; Schaeffer, D.J. Utility and Prognostic Significance of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Dogs with Septic Peritonitis. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2018, 54, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierini, A.; Gori, E.; Lippi, I.; Ceccherini, G.; Lubas, G.; Marchetti, V. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio, Nucleated Red Blood Cells and Erythrocyte Abnormalities in Canine Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome. Res. Vet. Sci. 2019, 126, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Domínguez, A.; Cristobal-Verdejo, J.I.; López-Espinar, C.; Fontela-González, S.; Vázquez, S.; Justo-Domínguez, J.; González-Caramazana, J.; Bragado-Cuesta, M.; Álvarez-Punzano, A.; Herrería-Bustillo, V.J. Retrospective Evaluation of Hematological Ratios in Canine Parvovirosis: 401 Cases. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2023, 38, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, S. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and Platelet-to-lymphocyte Ratios in Dogs and Cats with Acute Pancreatitis. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2021, 50, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinler Ay, C. Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio as a Prognostic Biomarker in Puppies with Acute Diarrhea. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2022, 32, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.M.; Gicking, J.C.; Keys, D.A. Evaluation of Red Blood Cell Distribution Width, Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte Ratio, and Other Hematologic Parameters in Canine Acute Pancreatitis. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2023, 33, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skor, O.; Fuchs-Baumgartinger, A.; Tichy, A.; Kleiter, M.; Schwendenwein, I. Pretreatment Leukocyte Ratios and Concentrations as Predictors of Outcome in Dogs with Cutaneous Mast Cell Tumours. Vet. Comp. Oncol. 2017, 15, 1333–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sottnik, J.L.; Rao, S.; Lafferty, M.H.; Thamm, D.H.; Morley, P.S.; Withrow, S.J.; Dow, S.W. Association of Blood Monocyte and Lymphocyte Count and Disease-Free Interval in Dogs with Osteosarcoma. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2010, 24, 1439–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconato, L.; Martini, V.; Stefanello, D.; Moretti, P.; Ferrari, R.; Comazzi, S.; Laganga, P.; Riondato, F.; Aresu, L. Peripheral Blood Lymphocyte/Monocyte Ratio as a Useful Prognostic Factor in Dogs with Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Receiving Chemoimmunotherapy. Vet. J. 2015, 206, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, R.; Oliveira, J.; Jorge, R.; Marcos, C.; Rosales, C. Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio and Principal Component Analysis Offer Prognostic Advantage for Dogs with Mammary Tumors. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1187271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristóbal, J.I.; Duque, F.J.; Usón-Casaús, J.; Barrera, R.; López, E.; Pérez-Merino, E.M. Complete Blood Count-Derived Inflammatory Markers Changes in Dogs with Chronic Inflammatory Enteropathy Treated with Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Animals 2022, 12, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipe, S.; Dall’ara, P.; Razzuoli, E.; Ciliberti, M.G.; Becher, A.; Acke, E.; Serrano, G.; Kiefer, I.; Alef, M.; Von Bomhard, W.; et al. Evaluation of the Blood Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) as a Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarker in Dogs with Portosystemic Shunt. Vet. Sci. 2024, 2024, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuna, G.E. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Dogs With Various Degrees of Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease. Egypt. J. Vet. Sci. 2024, 55, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeProspero, D.J.; Hess, R.S.; Silverstein, D.C. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio Is Increased in Dogs with Acute Congestive Heart Failure Secondary to Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease Compared to Both Dogs with Heart Murmurs and Healthy Controls. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2023, 261, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becher, A.; Suchodolski, J.S.; Steiner, J.M.; Heilmann, R.M. Blood Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) as a Diagnostic Marker in Dogs with Chronic Enteropathy. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2021, 33, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, E.; Pierini, A.; Gori, E.; Lucarelli, C.; Lubas, G.; Marchetti, V. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) in Canine Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, L.; Morris, J.; Pratschke, K.; Mellor, D.; Scase, T.; Macfarlane, M.; Mclauchlan, G. Diagnostic Value of Neutrophil-Lymphocyte and Albumin-Globulin Ratios in Canine Soft Tissue Sarcoma. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2016, 57, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rejec, A.; Butinar, J.; Gawor, J.; Petelin, M. Evaluation of Complete Blood Count Indices (NLR, PLR, MPV/PLT, and PLCRi) in Healthy Dogs, Dogs with Periodontitis, and Dogs with Oropharyngeal Tumors as Potential Biomarkers of Systemic Inflammatory Response. J. Vet. Dent. 2017, 34, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, G.; Baxarias, M.; Solano-Gallego, L.; Martínez-Flórez, I.; Mateu, C.; Pennisi, M.G. Clinical Significance of Blood Cell Ratios in Healthy and Sick Leishmania Infantum-Seropositive Dogs. Parasites Vectors 2024, 17, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchesi, M.C.; Maggi, G.; Cremonini, V.; Miglio, A.; Contiero, B.; Guglielmini, C.; Antognoni, M.T. Monocytes Count, NLR, MLR and PLR in Canine Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Animals 2024, 14, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaimo, C.; De Feo, G.; Lubas, G.; Gavazza, A. Utility and Prognostic Significance of Leukocyte Ratios in Dogs with Primary Immune-Mediated Hemolytic Anemia. Vet. Res. Commun. 2023, 47, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierini, A.; Esposito, G.; Gori, E.; Benvenuti, E.; Ruggiero, P.; Lubas, G.; Marchetti, V. Platelet Abnormalities and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratios in Canine Immunosuppressant-Responsive and Non-Responsive Enteropathy: A Retrospective Study in 41 Dogs. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2021, 83, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rösch, S.; Woitas, J.; Neumann, S.; Alef, M.; Kiefer, I.; Oechtering, G. Diagnostic Benefits of Platelet-to-Lymphocyte, Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte, and Albumin-to-Globulin Ratios in Dogs with Nasal Cavity Diseases. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, C.; Hsu, P.; Chen, S.; Huang, S.; Chan, W.L.; Lin, S.; Chou, C.; Chen, J.; Pan, J.; et al. Systemic Immune-inflammation Index (SII) Predicted Clinical Outcome in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 50, e13230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, T. Role of Systemic Immune-inflammation Index in Asthma and NSAID-exacerbated Respiratory Disease. Clin. Respir. J. 2021, 15, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Hu, T.; Wang, J.; Xiao, R.; Liao, X.; Liu, M.; Sun, Z. Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index as a Potential Biomarker of Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 933913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.-H.; Huang, D.-H.; Chen, Z.-Y. Prognostic Role of Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index in Solid Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 75381–75388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.S.; Nowosh, V.; López, R.V.M.; Massoco, C.d.O. Association of Systemic Inflammatory and Immune Indices With Survival in Canine Patients With Oral Melanoma, Treated With Experimental Immunotherapy Alone or Experimental Immunotherapy Plus Metronomic Chemotherapy. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 888411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Galea, A.; Cristóbal-Verdejo, J.I.; Macías-García, B.; Nicolás-Barceló, P.; Barrera-Chacón, R.; Ruiz-Tapia, P.; Zaragoza-Bayle, M.C.; Duque-Carrasco, F.J. Determination of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio, Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index in Dogs with Leptospirosis. Vet. Res. Commun. 2024, 48, 4105–4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Galea, A.; Cristóbal-Verdejo, J.I.; Barrera-Chacón, R.; Macías-García, B.; González-Solís, M.A.; Nicolás-Barceló, P.; García-Ibáñez, A.B.; Ruíz-Tapia, P.; Duque-Carrasco, F.J. Clinical Importance of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio, Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index in Dogs with Leishmaniasis. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2024, 107, 102148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuna, G.E.; Ulutas, B. The Systemic-Immune Inflammatory Index in Naturally Obese Dogs. Assiut Vet. Med. J. 2024, 70, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrichs, K.R.; Harr, K.E.; Freeman, K.P.; Szladovits, B.; Walton, R.M.; Barnhart, K.F.; Blanco-Chavez, J. ASVCP Reference Interval Guidelines: Determination of de Novo Reference Intervals in Veterinary Species and Other Related Topics. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2012, 41, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, J.; Chang, Y.M.R.; Szladovits, B.; Davison, L.J.; Garden, O.A. Breed-Specific Hematological Phenotypes in the Dog: A Natural Resource for the Genetic Dissection of Hematological Parameters in a Mammalian Species. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly, S.L.; Nelson, S.; Jones, T.; Kahn, J.; Constable, P.D. The Effect of Age and Sex on Selected Hematologic and Serum Biochemical Analytes in 4,804 Elite Endurance-Trained Sled Dogs Participating in the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race Pre-Race Examination Program. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, B.A. Immunosenescence and Inflammaging in Dogs and Cats: A Narrative Review. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2025, 39, e70159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, D.; Chae, Y.; Kim, C.; Koo, Y.; Lee, D.; Yun, T.; Chang, D.; Kang, B.T.; Yang, M.P.; Kim, H. Severity of Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease in Dogs May Be Predicted Using Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte and Monocyte-to-Lymphocyte Ratio. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2023, 84, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, M.J.; Kim, J.H. Prognostic Efficacy of Complete Blood Count Indices for Assessing the Presence and the Progression of Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease in Dogs. Animals 2023, 13, 2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton-Elliott, J.; Ambrose, E.; Christley, R.; Dukes-McEwan, J. White Blood Cell Differentials in Dogs with Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) in Comparison to Those in Dogs without Cardiac Disease. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2018, 59, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Yun, T.; Cha, S.; Oh, J.; Lee, D.; Koo, Y.; Chae, Y.; Yang, M.-P.; Kang, B.-T.; Kim, H. Can Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratios Be Used as Markers for Hypercortisolism in Dogs? Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2024, 61, 100890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaitaitis, G.; Webb, T.; Webb, C.; Sharkey, C.; Sharkey, S.; Waid, D.; Wagner, D.H. Canine Diabetes Mellitus Demonstrates Multiple Markers of Chronic Inflammation Including Th40 Cell Increases and Elevated Systemic-Immune Inflammation Index, Consistent with Autoimmune Dysregulation. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1319947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozalp, T.; Erdogan, S.; Ural, K.; Erdogan, H. Assessment of Novel Haematological Inflammatory Markers (NLR, SII, and SIRI) as Predictors of SIRS in Dogs with Canine Monocytic Ehrlichiosis. Vet. Stanica 2024, 56, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nah, E.H.; Kim, S.; Cho, S.; Cho, H.I. Complete Blood Count Reference Intervals and Patterns of Changes across Pediatric, Adult, and Geriatric Ages in Korea. Ann. Lab. Med. 2018, 38, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, J.M.; Deary, I.J. Sex Differences in Blood Cell Counts in the Lothian Birth Cohort 1921 between 79 and 87 Years. Maturitas 2011, 69, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radakovich, L.B.; Pannone, S.C.; Truelove, M.P.; Olver, C.S.; Santangelo, K.S. Hematology and Biochemistry of Aging—Evidence of “Anemia of the Elderly” in Old Dogs. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2017, 46, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).