What Makes Us React to the Abuse of Pets, Protected Animals, and Farm Animals: The Role of Attitudes, Norms, and Moral Obligation

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Setting

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Scenarios Depicting Situations of Animal Abuse

2.3.2. Social and Personal Norms

2.3.3. Moral Obligation

2.3.4. Reaction to Animal Abuse

2.3.5. Speciesism Scale

2.3.6. Animal Attitude Scale-10

2.3.7. Social Desirability Scale

2.3.8. Sociodemographic Characteristics

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Design and Data Analysis

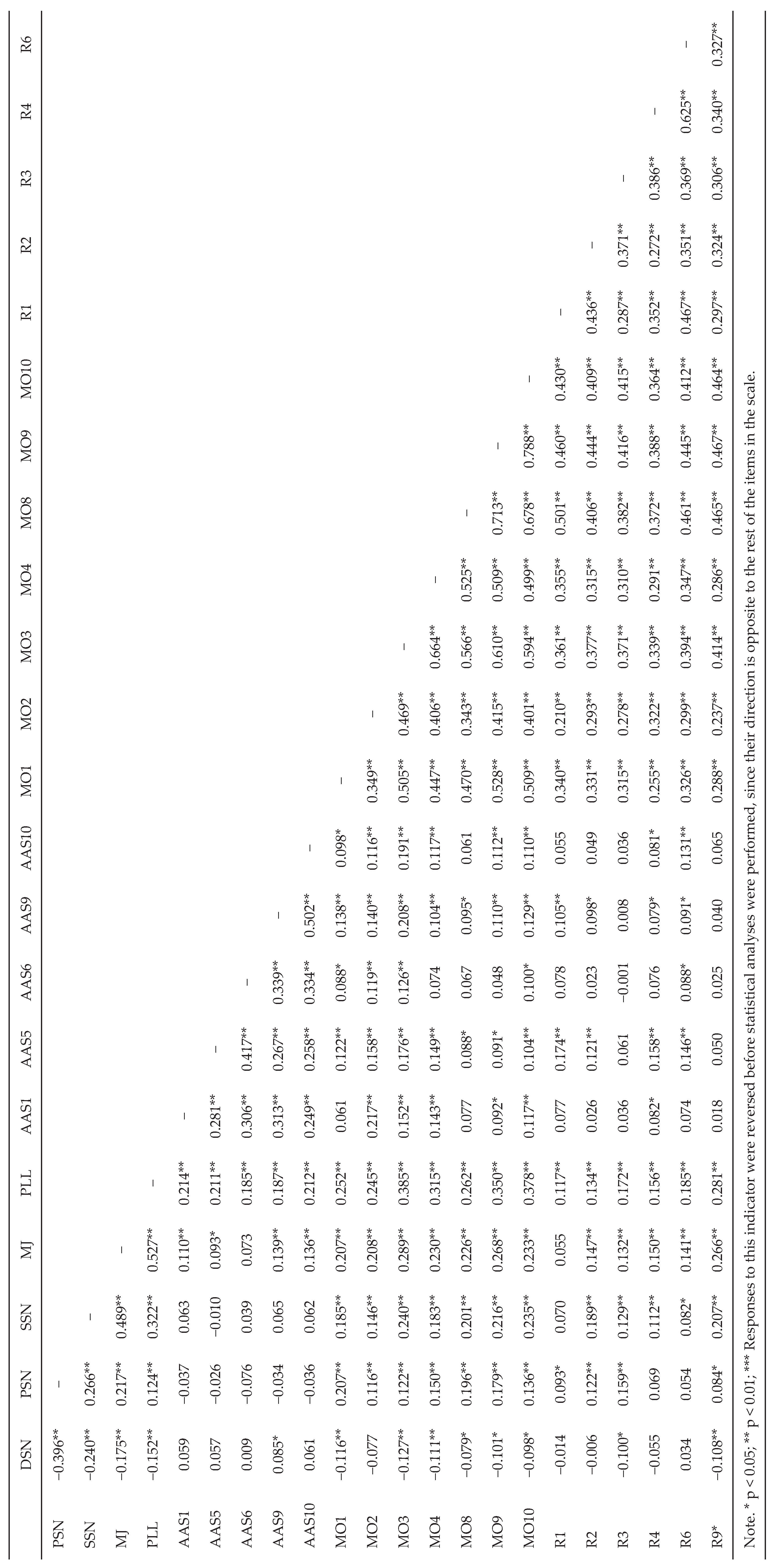

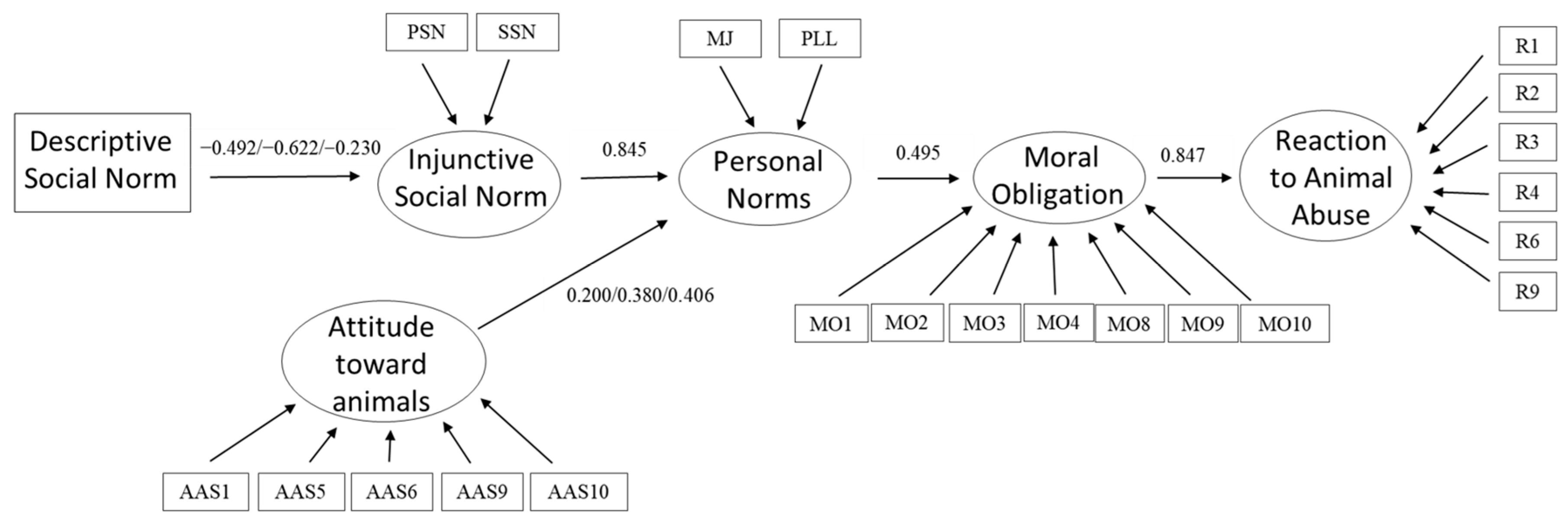

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Moral Obligation, Personal, and Social Norms

4.2. Attitudes Toward Animals

4.3. Limitations of the Study

4.4. Contributions to Animal–Human Relationship Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Bernuz-Beneitez, M.J.; María, G.A. Public opinion about punishment for animal abuse in Spain: Animal attributes as predictors of attitudes toward penalties. Anthrozoöss 2022, 35, 559–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhont, K.; Ioannidou, M. Health, environmental, and animal rights motives among omnivores, vegetarians, and vegans and the associations with meat, dairy, and egg commitment. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 118, 105196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie-Mohr, D.; Nemiroff, L.S.; Beers, L.; Desmarais, S. Determinants of responsible environmental behavior. J. Soc. Issues 1995, 51, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F. What is measured in pro-environmental behavior research? J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 98, 102381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alleyne, E.; Parfitt, C. Adult-perpetrated animal abuse: A systematic literature review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2019, 20, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bègue, L.; Garcet, S.; Weinberger, D. Intentional Harm to Animals: A Multidimensional Approach. Aggress. Behav. 2025, 51, e70028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monsalve, S.; Ferreira, F.; Garcia, R. The connection between animal abuse and interpersonal violence: A review from the veterinary perspective. Res. Vet. Sci. 2017, 114, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Kumar, D.; Katiyar, R. Antecedents of continuous purchase behavior for sustainable products: An integrated conceptual framework and review. J. Consum. Behav. 2025, 24, 1685–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Norman, P. Attitudes, intentions, and behavior change. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2025, 77, 6.1–6.27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.C. Attitudes and motivation. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 1988, 9, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, C.; Mollborn, S. Norms: An integrated framework. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2020, 46, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, M.; Woodyatt, L. The power and pitfalls of social norms. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2025, 76, 583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J.; Dhont, K.; Salmen, A. Individual differences in effective animal advocacy: Moderating effects of gender identity and speciesism. Anthrozoös 2024, 37, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The advantages of an inclusive definition of attitude. Soc. Cogn. 2007, 25, 582–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollum, S.; Longmire, D.; Buffington-Vollum, J. Moral disengagement and attitudes about violence toward animals. Soc. Anim. 2004, 12, 209–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviola, L.; Capraro, V. Liking but devaluing animals: Emotional and deliberative paths to speciesism. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2020, 11, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bègue, L.; Vezirian, K. Instrumental harm toward animals in a Milgram-like experiment in France. In Animal Abuse and Interpersonal Violence: A Psycho-Criminological Understanding; Chan, H.C., Wong, R.W.Y., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- Dhont, K.; Hodson, G.; Loughnan, S.; Amiot, C.E. Rethinking human-animal relations: The critical role of social psychology. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2019, 22, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahane, G.; Caviola, L. Are the folk utilitarian about animals? Philos. Stud. 2023, 180, 1081–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vera, A.; Ruiz, C.; Martin, A.M. Reaction against farm animal abuse: The role of animal attitude and speciesism. Acción. Psicol. 2023, 20, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, A.M.; Vera, A.; Marrero, R.J.; Hernández, B. Bystanders’ reaction to animal abuse in relation to psychopathy, empathy with people and empathy with nature. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1124162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; del Carmen Aguilar-Luzón, M.; Hernández, B. Bases teóricas que guían a la psicología de la conservación ambiental. Papeles Psicól. 2019, 40, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, B.; Martín, A.M.; Ruiz, C.; Hidalgo, M.C. The role of place identity and place attachment in breaking environmental protection laws. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, A.M.; Hernández, B.; Frías-Armenta, M.; Hess, S. Why ordinary people comply with environmental laws: A structural model on normative and attitudinal determinants of illegal anti-ecological behavior. Legal. Criminol. Psychol. 2014, 19, 80–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savari, M.; Sheheytavi, A.; Amghani, M.S. Promotion of adopting preventive behavioral intention toward biodiversity degradation among Iranian farmers. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 43, e02450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reno, R.R.; Cialdini, R.B.; Kallgren, C.A. The transsituational influence of social norms. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Kallgren, C.A.; Reno, R.R. A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and re-evaluation. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 24, 201–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thørgensen, J. Norms for environmentally responsible behavior: An extended taxonomy. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.R. Why People Obey the Law; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S. Normative influences on altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helferich, M.; Thøgersen, J.; Bergquist, M. Direct and mediated impacts of social norms on pro-environmental behaviour. Glob. Environ. Change 2023, 80, 102680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1974, 13, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C.; Hogg, M.A.; Oakes, P.J.; Reicher, S.D.; Wetherell, M.S. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Balzani, A.; Hanlon, A. Factors that influence farmers’ views on farm animal welfare: A semi-systematic review and thematic analysis. Animals 2020, 10, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.H.; Hartmann, M. To purchase or not to purchase? Drivers of consumers’ preferences for animal welfare in their meat choice. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, L.; Palmer, S.B.; Faber, N.S. The development of speciesism: Age-related differences in the moral view of animals. Soc Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2023, 14, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabucedo, J.M.; Dono, M.; Alzate, M.; Seoane, G. The importance of protesters’ morals: Moral obligation as a key variable to understand collective action. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasello, M. The role of roles in uniquely human cognition and sociality. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2020, 50, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. J. Res. Pers. 1985, 19, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, L.G.; Tuson, K.M.; Green-Demers, I.; Noels, K.; Beaton, A.M. Why are you doing things for the environment? The Motivation Toward the Environment Scale (MTES). J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 437–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, A.J.; Guertin, C.; Pelletier, L.G. Motivated to eat green or your greens? Comparing the role of motivation towards the environment and for eating regulation on ecological eating behaviours—A Self-Determination Theory perspective. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 91, 104570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavergne, S.; Mouquet, N.; Thuiller, W.; Ronce, O. Biodiversity and climate change: Integrating evolutionary and ecological responses of species and communities. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2010, 41, 321–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, T.; Otto, S. Explaining the difference between the predictive power of value orientations and self-determined motivation for proenvironmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 73, 101555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, A.M.; Hernández, B.; Alonso, I. Pro-environmental motivation and regulation to respect environmental laws as predictors of illegal anti-environmental behavior. Psyecology 2017, 8, 33–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.R. Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2006, 57, 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.R. Afterword. In Why People Obey the Law; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, S.; Sanz, J.; Espinosa, R.; Gesteira, C.; García-Vera, M.P. La Escala de Deseabilidad social de Marlowe-Crowne: Baremos para la población general española y desarrollo de una versión breve. An. Psicol. 2016, 32, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviola, L.; Everett, J.A.C.; Faber, N.S. The moral standing of animals: Towards a psychology of speciesism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 116, 1011–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez-Yera, C.; Ordóñez-Carrasco, J.L.; Sánchez-Castelló, M.; Rojas-Tejada, A.J. Spanish Adaptation and Psychometric Properties of the Animal Attitudes Scale and the Speciesism Scale. Hum. Anim. Interact. Bull. 2021, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H.A.; Grayson, S.; McCord, D. Brief measures of the Animal Attitude Scale. Anthrozoös 2015, 28, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowne, D.P.; Marlowe, D. A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. J. Consult. Psychol. 1960, 24, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Winklhofer, H.M. Index construction with formative indicators: An alternative to scale development. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ato, M.; López, J.J.; Benavente, A. Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. An. Psicol. 2013, 2, 1038–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Cabrera, J.A. 2021. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/ullrtoolbox/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Gaskin, J.E.; Lowry, P.B.; Rosengren, W.; Fife, P.T. Essential validation criteria for rigorous covariance-based structural equation modelling. Inf. Syst. J. 2025, 35, 1630–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.; Steg, L. Relationships between value orientations, self-determined motivational types and pro-environmental behavioural intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. Multi-Discip. J. 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevillano, V.; Fiske, S.T. Animals as social groups: An intergroup relations analysis of human-animal conflicts. In Why People Love and Exploit Animals: Bridging Insights from Academia and Advocacy; Dhont, K., Hodson, G., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; pp. 260–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, S.; Rodríguez-Rey, R.; Sorrel, M.A. Does beauty matter? The effect of perceived attractiveness on children’s moral judgments of harmful actions against animals. Environ. Behav. 2022, 54, 247–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SE | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSN | 2.133 | 0.0982 | 2.45 | 1.200 | 0.7475 |

| PSN | 7.795 | 0.0942 | 2.35 | −1.348 | 1.5357 |

| SSN | 9.101 | 0.0801 | 2.00 | −3.052 | 9.6021 |

| MJ | 9.708 | 0.0492 | 1.23 | −5.735 | 36.3516 |

| PLL | 9.550 | 0.0520 | 1.30 | −3.962 | 18.9455 |

| AAS1 | 7.785 | 0.1386 | 3.46 | −1.376 | 0.3407 |

| AAS5 | 7.837 | 0.1199 | 2.99 | −1.425 | 0.9842 |

| AAS6 | 8.024 | 0.1108 | 2.77 | −1.420 | 1.1704 |

| AAS9 | 7.298 | 0.1437 | 3.59 | −1.072 | −0.3583 |

| AAS10 | 7.191 | 0.1405 | 3.51 | −0.980 | −0.4936 |

| MO1 | 7.877 | 0.1086 | 2.71 | −1.352 | 1.0547 |

| MO2 | 8.795 | 0.0812 | 2.03 | −2.091 | 4.4476 |

| MO3 | 8.830 | 0.0811 | 2.03 | −2.179 | 4.7577 |

| MO4 | 8.279 | 0.1021 | 2.55 | −1.644 | 1.9834 |

| MO8 | 7.904 | 0.1018 | 2.54 | −1.261 | 0.9368 |

| MO9 | 8.510 | 0.0810 | 2.02 | −1.545 | 2.0782 |

| MO10 | 8.567 | 0.0798 | 1.99 | −1.612 | 2.4705 |

| R1 | 6.396 | 0.1281 | 3.20 | −0.524 | −0.8964 |

| R2 | 7.942 | 0.1084 | 2.71 | −1.401 | 1.1913 |

| R3 | 7.567 | 0.1093 | 2.73 | −1.079 | 0.3434 |

| R4 | 8.167 | 0.1032 | 2.58 | −1.612 | 1.9753 |

| R6 | 6.748 | 0.1313 | 3.28 | −0.709 | −0.7535 |

| R9 * | 8.322 | 0.0943 | 2.35 | −1.591 | 1.9320 |

| Latent Variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observable Variables | Estimate | z | SE | SD |

| Injunctive Social Norm (ω = 0.42) | ||||

| PSN | 1 | 0.459 | ||

| SSN | 1.277 | 7.069 *** | 0.181 | 0.623 |

| Personal Norm (ω = 0.71) | ||||

| MJ | 1 | 0.591 | ||

| PLL | 1.074 | 11.475 *** | 0.094 | 0.806 |

| Attitudes toward animals (ω = 0.71) | ||||

| AAS1 | 1 | 0.529 | ||

| AAS5 | 1.014 | 7.622 *** | 0.133 | 0.557 |

| AAS6 | 1.045 | 7.683 *** | 0.136 | 0.652 |

| AAS9 | 1.097 | 7.299 *** | 0.150 | 0.565 |

| AAS10 | 1.007 | 6.933 *** | 0.145 | 0.519 |

| Moral Obligation (ω = 0.88) | ||||

| MO1 | 1 | 0.55 | ||

| MO2 | 0.619 | 10.083 *** | 0.061 | 0.469 |

| MO3 | 0.891 | 16.826 *** | 0.053 | 0.689 |

| MO4 | 0.981 | 15.743 *** | 0.062 | 0.566 |

| MO8 | 1.249 | 17.725 *** | 0.07 | 0.777 |

| MO9 | 1.023 | 17.417 *** | 0.059 | 0.824 |

| MO10 | 0.977 | 15.583 *** | 0.063 | 0.802 |

| Reaction to Animal Abuse (ω = 0.78) | ||||

| R1 | 1 | 0.518 | ||

| R2 | 0.812 | 13.000 *** | 0.062 | 0.488 |

| R3 | 0.758 | 11.084 *** | 0.068 | 0.486 |

| R4 | 0.694 | 9.720 *** | 0.071 | 0.489 |

| R6 | 1.009 | 14.451 *** | 0.070 | 0.520 |

| R9 * | 0.674 | 10.807 *** | 0.062 | 0.454 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruiz, C.; Vera, A.; Rosales, C.; Martín, A.M. What Makes Us React to the Abuse of Pets, Protected Animals, and Farm Animals: The Role of Attitudes, Norms, and Moral Obligation. Animals 2025, 15, 3339. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223339

Ruiz C, Vera A, Rosales C, Martín AM. What Makes Us React to the Abuse of Pets, Protected Animals, and Farm Animals: The Role of Attitudes, Norms, and Moral Obligation. Animals. 2025; 15(22):3339. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223339

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuiz, Cristina, Andrea Vera, Christian Rosales, and Ana M. Martín. 2025. "What Makes Us React to the Abuse of Pets, Protected Animals, and Farm Animals: The Role of Attitudes, Norms, and Moral Obligation" Animals 15, no. 22: 3339. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223339

APA StyleRuiz, C., Vera, A., Rosales, C., & Martín, A. M. (2025). What Makes Us React to the Abuse of Pets, Protected Animals, and Farm Animals: The Role of Attitudes, Norms, and Moral Obligation. Animals, 15(22), 3339. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223339