Acute Effect of Furosemide on Left Atrium Size in Cats with Acute Left-Sided Congestive Heart Failure

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Inclusion Criteria

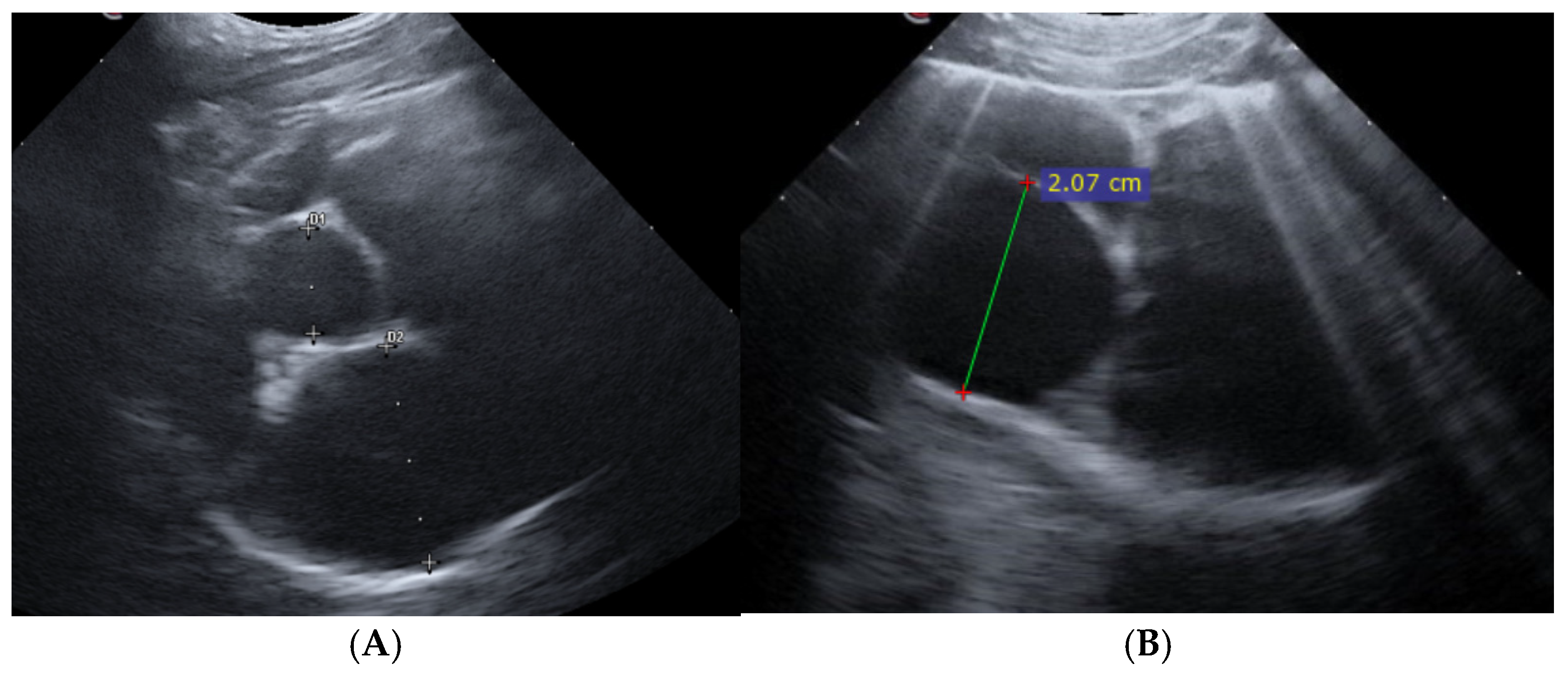

2.2. Point-of-Care Ultrasound Examination and Study Design

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Sample, Clinical and Lung Ultrasound Findings

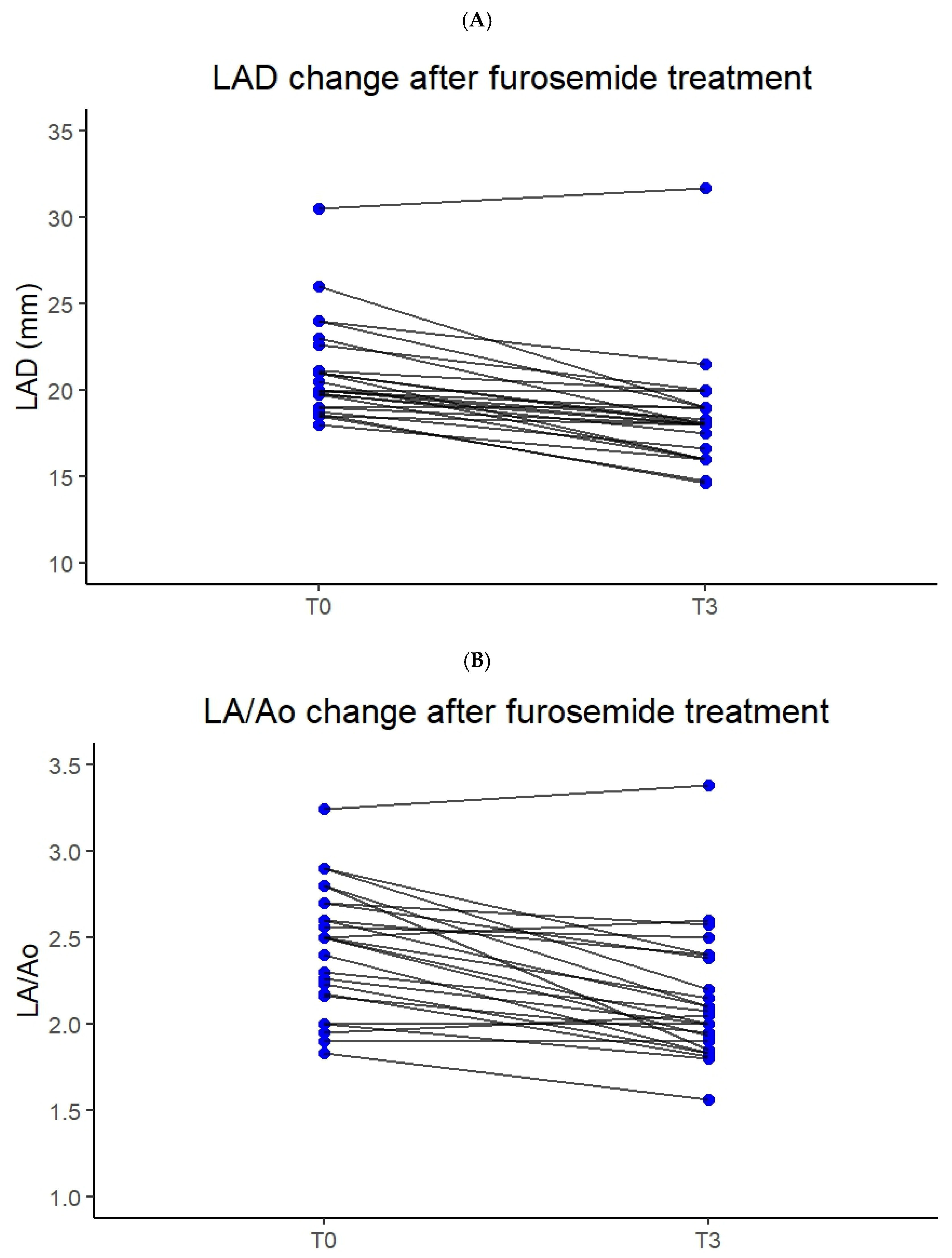

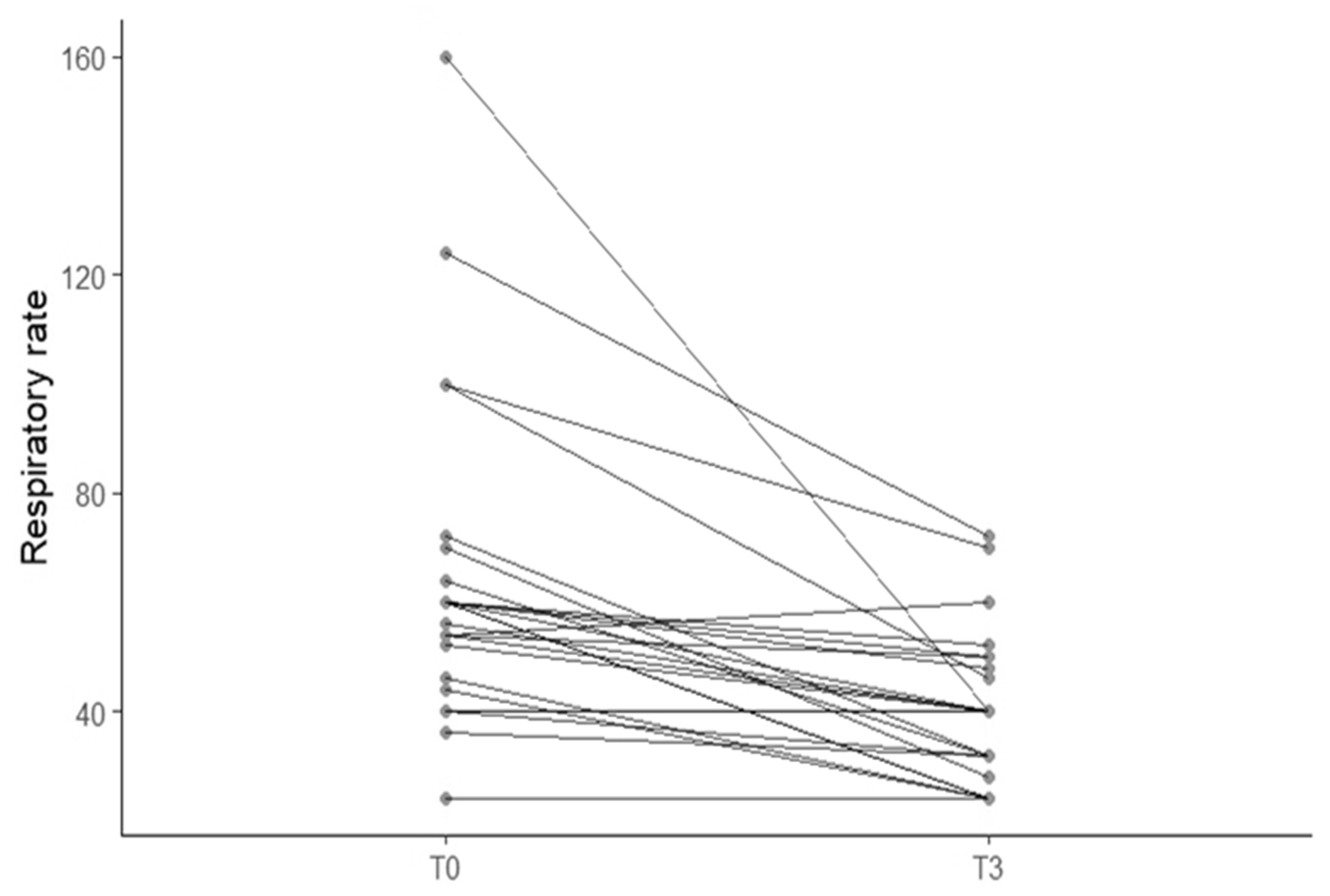

3.2. Correlation Between Furosemide Dose, Breathing Improvement and Left Atrial Size

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abboud, N.; Deschamps, J.Y.; Joubert, M.; Roux, F.A. Emergency Dyspnea in 258 Cats: Insights from the French RAPID CAT Study. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Dukes-McEwan, J. Clinical signs and left atrial size in cats with cardiovascular disease in general practice. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2012, 53, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, W.P.; Gaber, C.E.; Jacobs, G.J.; Kaplan, P.M.; Lombard, C.W.; Moise, N.S.; Moses, B.L. Recommendations for standards in transthoracic two-dimensional echocardiography in the dog and cat. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 1993, 7, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, K. Focused Cardiac Ultrasonography in Cats. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2021, 51, 1183–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D. Pulmonary edema. In Textbook of Respiratory Disease in Dogs and Cats; King, L., Ed.; WB Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2004; pp. 487–497. [Google Scholar]

- Diana, A.; Perfetti, S.; Valente, C.; Baron Toaldo, M.; Pey, P.; Cipone, M.; Poser, H.; Guglielmini, C. Radiographic features of cardiogenic pulmonary oedema in cats with left-sided cardiac disease: 71 cases. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2022, 24, e568–e579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Ishikawa, T.; Hamabe, L.; Aytemiz, D.; Huai-Che, H.; Fukushima, R.; Machida, N.; Tanaka, R. The effect of furosemide on left atrial pressure in dogs with mitral valve regurgitation. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2011, 25, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis Fuentes, V.; Abbott, J.; Chetboul, V.; Côté, E.; Fox, P.R.; Häggström, J.; Kittleson, M.D.; Schober, K.; Stern, J.A. ACVIM consensus statement guidelines for the classification, diagnosis, and management of cardiomyopathies in cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2020, 34, 1062–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferasin, L.; DeFrancesco, T. Management of acute heart failure in cats. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2015, 17 (Suppl. 1), S173–S189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, E. Feline Congestive Heart Failure: Current Diagnosis and Management. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2017, 47, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Boedec, K.; Arnaud, C.; Chetboul, V.; Trehiou-Sechi, E.; Pouchelon, J.L.; Gouni, V.; Reynolds, B.S. Relationship between paradoxical breathing and pleural diseases in dyspneic dogs and cats: 389 cases (2001–2009). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2012, 240, 1095–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungvall, I.; Rishniw, M.; Porciello, F.; Häggström, J.; Ohad, D. Sleeping and resting respiratory rates in healthy adult cats and cats with subclinical heart disease. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2014, 16, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porciello, F.; Rishniw, M.; Ljungvall, I.; Ferasin, L.; Häggström, J.; Ohad, D.G. Sleeping and resting respiratory rates in dogs and cats with medically controlled left-sided congestive heart failure. Vet. J. 2016, 207, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkstra, E.; Teske, E.; Szatmári, V. Respiratory rate of clinically healthy cats measured in veterinary consultation rooms. Vet. J. 2018, 234, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Ruiz, M.A.; Reinero, C.R.; Vientos-Plotts, A.; Grobman, M.E.; Silverstein, D.; Gomes, E.; Le Boedec, K. Association between respiratory clinical signs and respiratory localization in dogs and cats with abnormal breathing patterns. Vet. J. 2021, 277, 105761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Ruiz, M.A.; Reinero, C.R.; Vientos-Plotts, A.; Grobman, M.E.; Silverstein, D.; Le Boedec, K. Interclinician agreement on the recognition of selected respiratory clinical signs in dogs and cats with abnormal breathing patterns. Vet. J. 2021, 277, 105760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, L.; Pivetta, M.; Humm, K. Diagnostic accuracy of a lung ultrasound protocol (Vet BLUE) for detection of pleural fluid, pneumothorax and lung pathology in dogs and cats. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2021, 62, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisciandro, G.R.; Lisciandro, S.C. Lung Ultrasound Fundamentals, “Wet Versus Dry” Lung, Signs of Consolidation in Dogs and Cats. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2021, 51, 1125–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łobaczewski, A.; Czopowicz, M.; Moroz, A.; Mickiewicz, M.; Stabińska, M.; Petelicka, H.; Frymus, T.; Szaluś-Jordanow, O. Lung Ultrasound for Imaging of B-Lines in Dogs and Cats—A Prospective Study Investigating Agreement between Three Types of Transducers and the Accuracy in Diagnosing Cardiogenic Pulmonary Edema, Pneumonia and Lung Neoplasia. Animals 2021, 11, 3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oricco, S.; Medico, D.; Tommasi, I.; Bini, R.M.; Rabozzi, R. Lung ultrasound score in dogs and cats: A reliability study. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2024, 38, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigot, M.; Boysen, S.R.; Masseau, I.; Letendre, J.A. Evaluation of B-lines with 2 point-of-care lung ultrasound protocols in cats with radiographically normal lungs. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2024, 34, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanstein, H.; Boysen, S.; Cole, L. Feline friendly POCUS: How to implement it into your daily practice. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2024, 26, 1098612X241276916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenise, A. Point-of-Care Lung Ultrasound in Small Animal Emergency and Critical Care Medicine: A Clinical Review. Animals 2025, 15, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanstein, H.K.J.; Langhorn, R.; Gommeren, K.; Boysen, S. Comparison of Two Lung Ultrasound Protocols for Identification and Distribution of B-, I-, and Z-Lines in Clinically Healthy Cats. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2025, 35, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M.Y.; Häggström, J.; Gordon, S.G.; Höglund, K.; Côté, E.; Lu, T.L.; Dirven, M.; Rishniw, M.; Hung, Y.W.; Ljungvall, I. Veterinary echocardiographers’ preferences for left atrial size assessment in cats: The BENEFIT project. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2024, 51, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittleson, M.D.; Côté, E. The Feline Cardiomyopathies: 1. General concepts. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2021, 23, 1009–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, F.E.; Kittleson, M.D. The effect of hydration status on the echocardiographic measurements of normal cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2007, 21, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, K.E.; Wetli, E.; Drost, W.T. Radiographic and echocardiographic assessment of left atrial size in 100 cats with acute left-sided congestive heart failure. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2014, 55, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsue, W.; Visser, L.C. Reproducibility of echocardiographic indices of left atrial size in dogs with subclinical myxomatous mitral valve disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2020, 34, 1779–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miliaux, S.; Hulsman, A.H.; Hugen, S.; Groesser, N.; Teske, E.; Szatmári, V. Acute Effect of Furosemide on Left Atrium Size in Cats with Acute Left-Sided Congestive Heart Failure. Animals 2025, 15, 3267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223267

Miliaux S, Hulsman AH, Hugen S, Groesser N, Teske E, Szatmári V. Acute Effect of Furosemide on Left Atrium Size in Cats with Acute Left-Sided Congestive Heart Failure. Animals. 2025; 15(22):3267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223267

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiliaux, Sarah, Alma H. Hulsman, Sanne Hugen, Niels Groesser, Erik Teske, and Viktor Szatmári. 2025. "Acute Effect of Furosemide on Left Atrium Size in Cats with Acute Left-Sided Congestive Heart Failure" Animals 15, no. 22: 3267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223267

APA StyleMiliaux, S., Hulsman, A. H., Hugen, S., Groesser, N., Teske, E., & Szatmári, V. (2025). Acute Effect of Furosemide on Left Atrium Size in Cats with Acute Left-Sided Congestive Heart Failure. Animals, 15(22), 3267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223267