Bird Diversity and Bird-Strike Risk at Lincang Boshang Airport

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

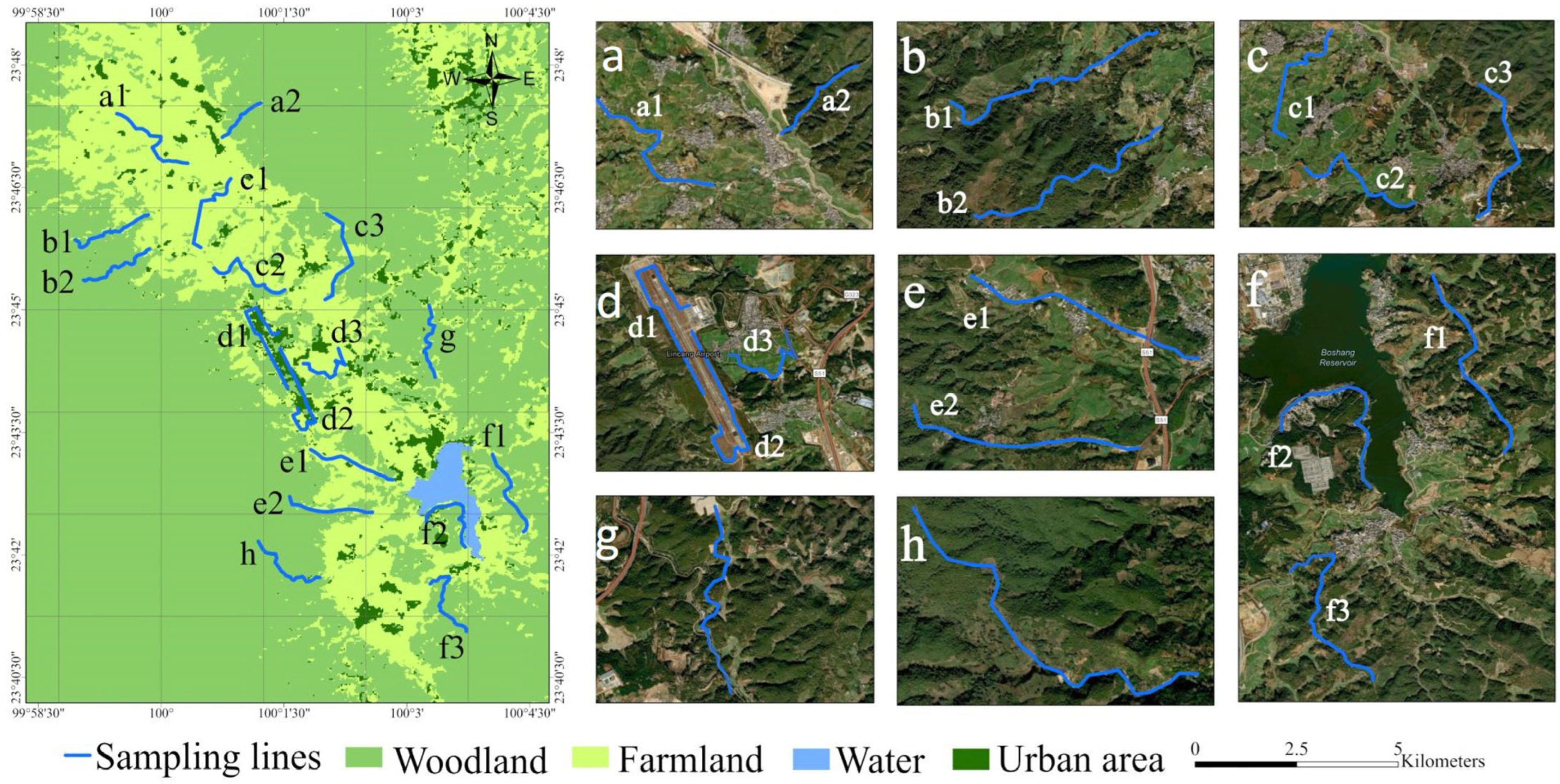

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Bird Surveys

2.3. Data Analysis

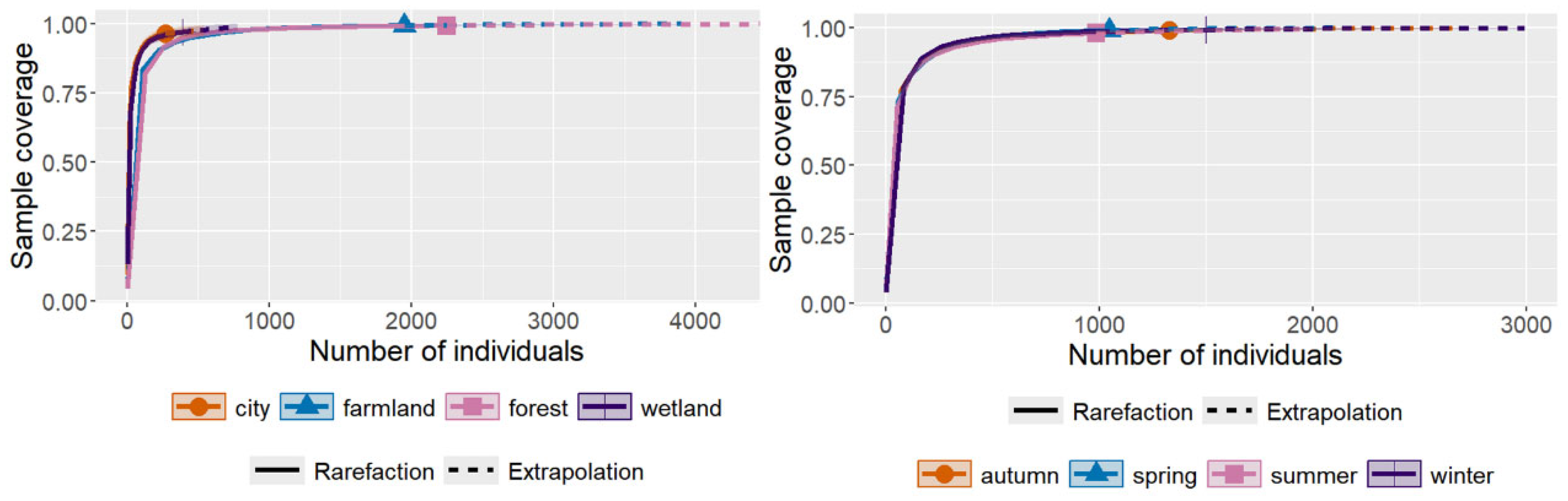

2.3.1. Species Accumulation Curves

2.3.2. Dominant Species Analysis

2.3.3. Calculation of Diversity Indices

- (1)

- Taxonomic Diversity

- (2)

- Functional Diversity

- (3)

- Phylogenetic Diversity

2.3.4. Functional and Phylogenetic Community Structure

2.3.5. Calculation of Bird Risk Value

- (1)

- Importance Value

- (2)

- Risk Coefficient

2.3.6. Data Analysis and Significance Testing

3. Results

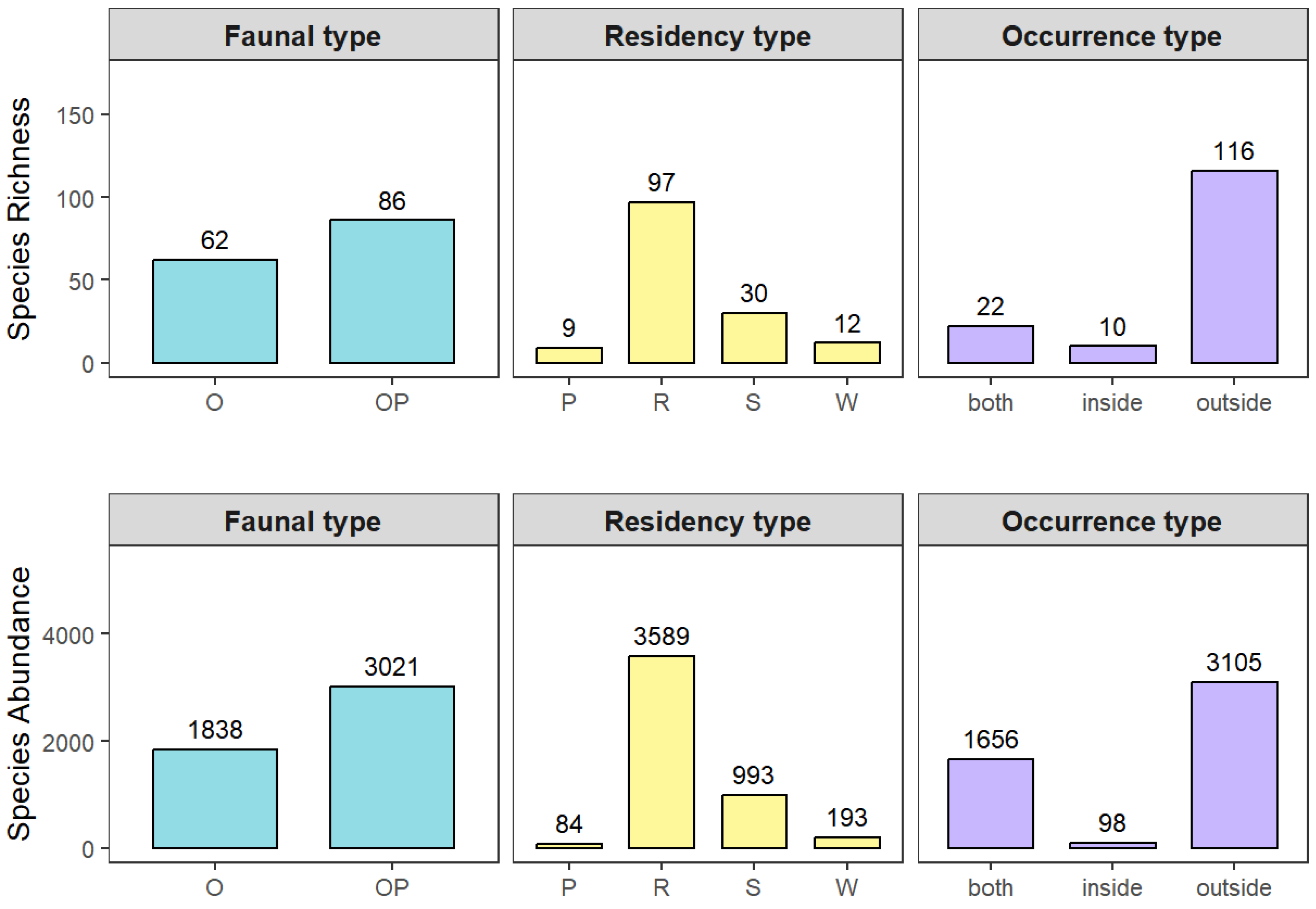

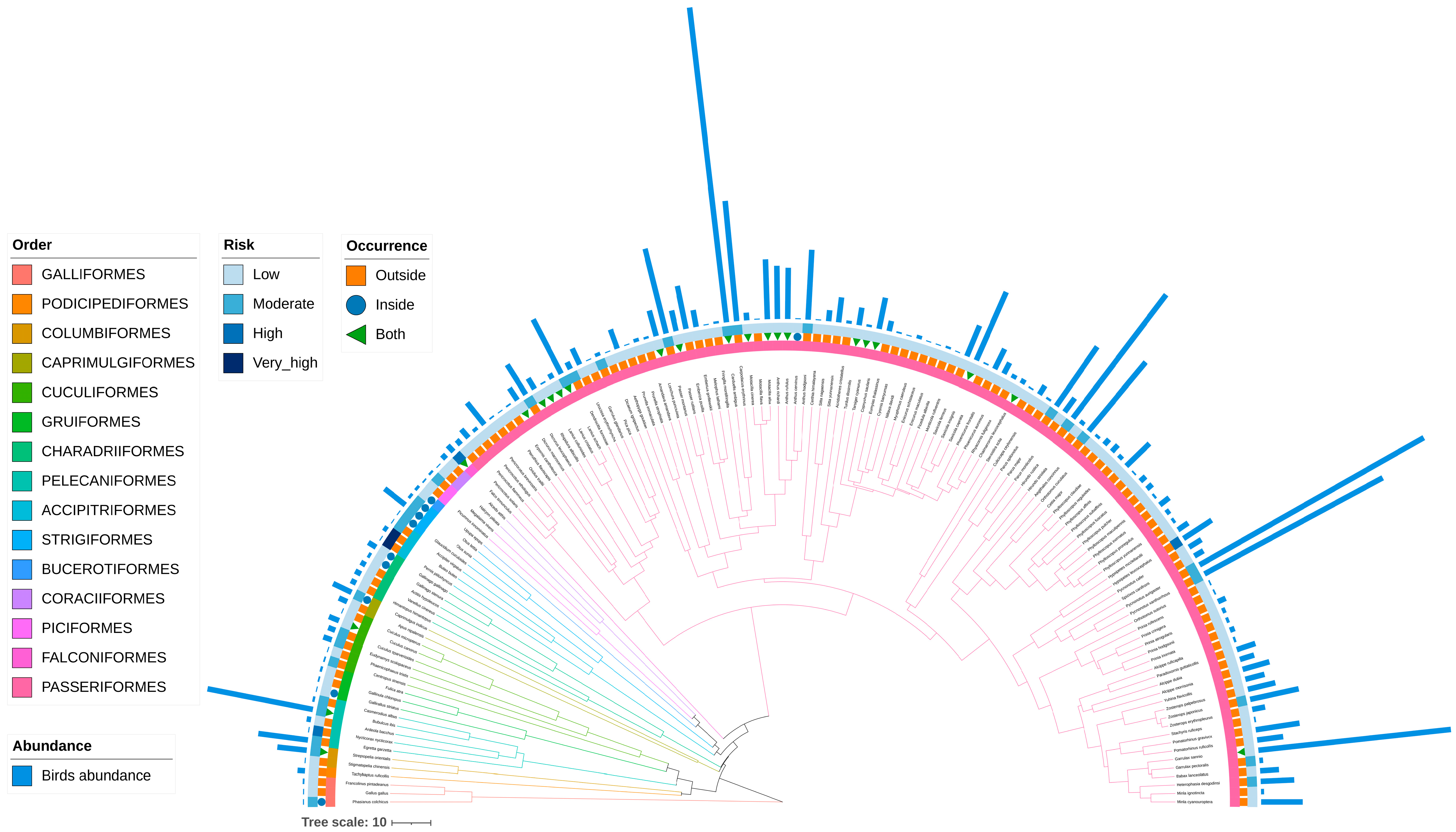

3.1. Bird Species Composition

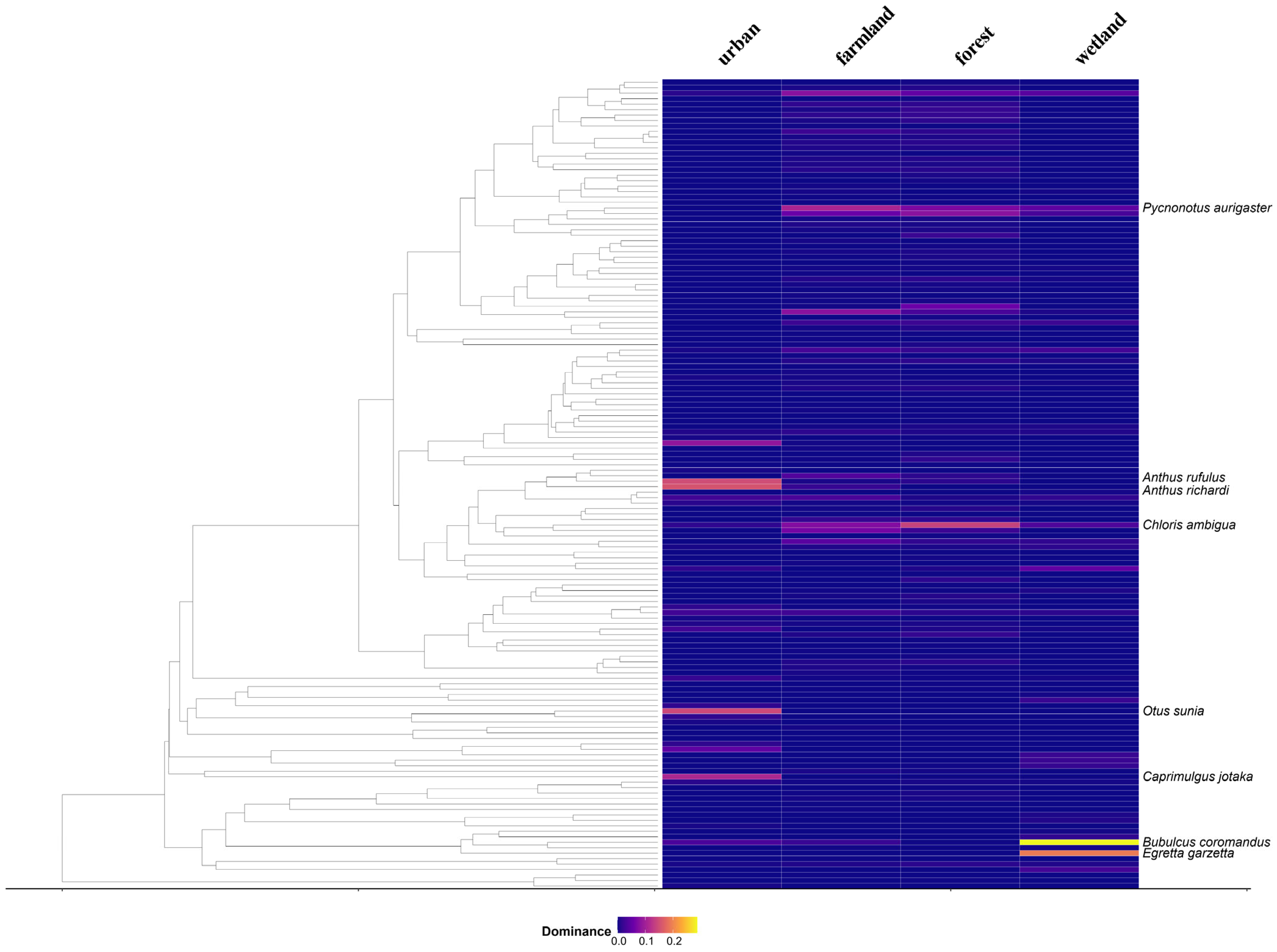

3.2. Analysis of Dominant Bird Species in the Community

3.3. Diversity Analysis Among Different Habitats

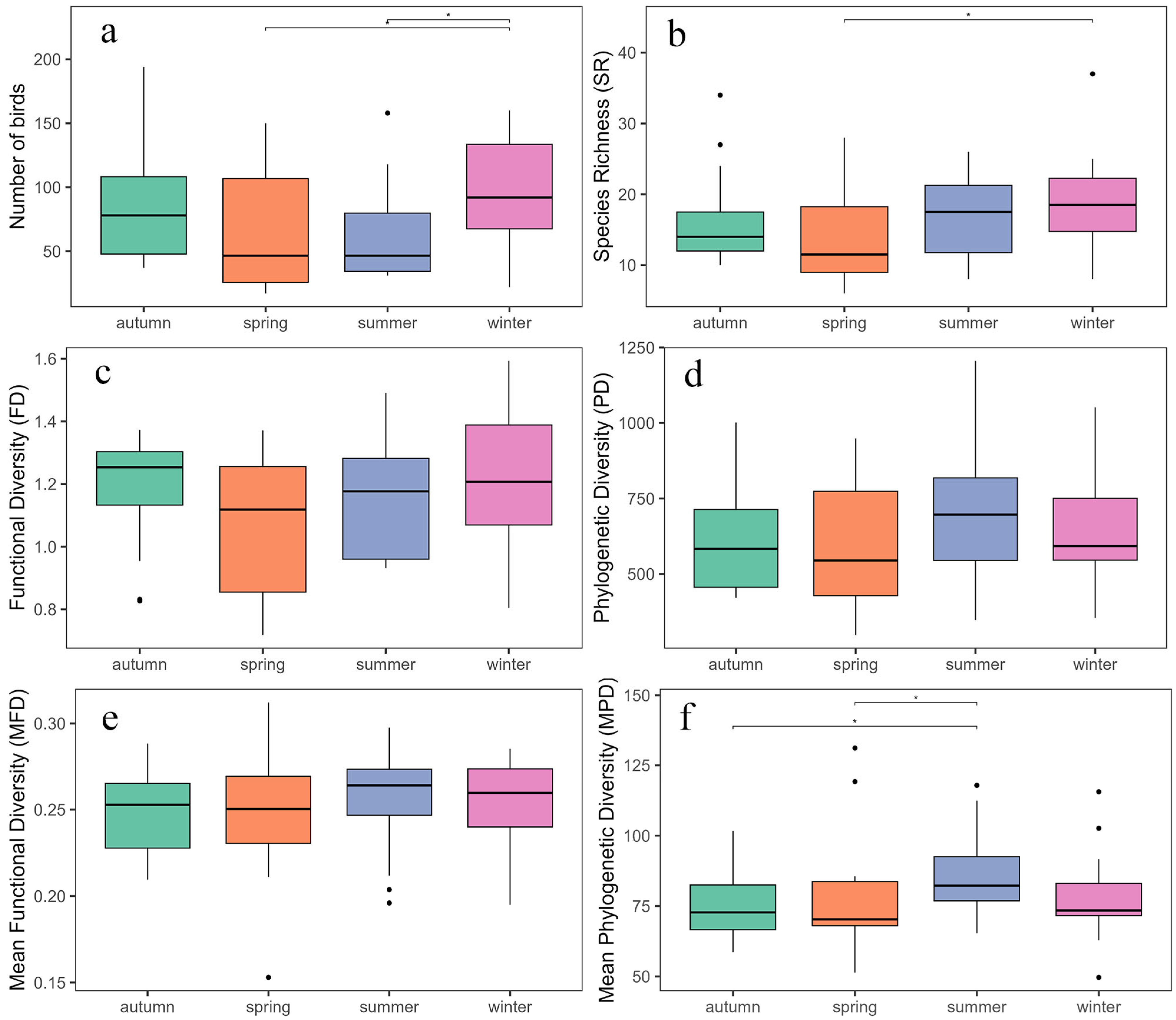

3.4. Seasonal Variation in Diversity

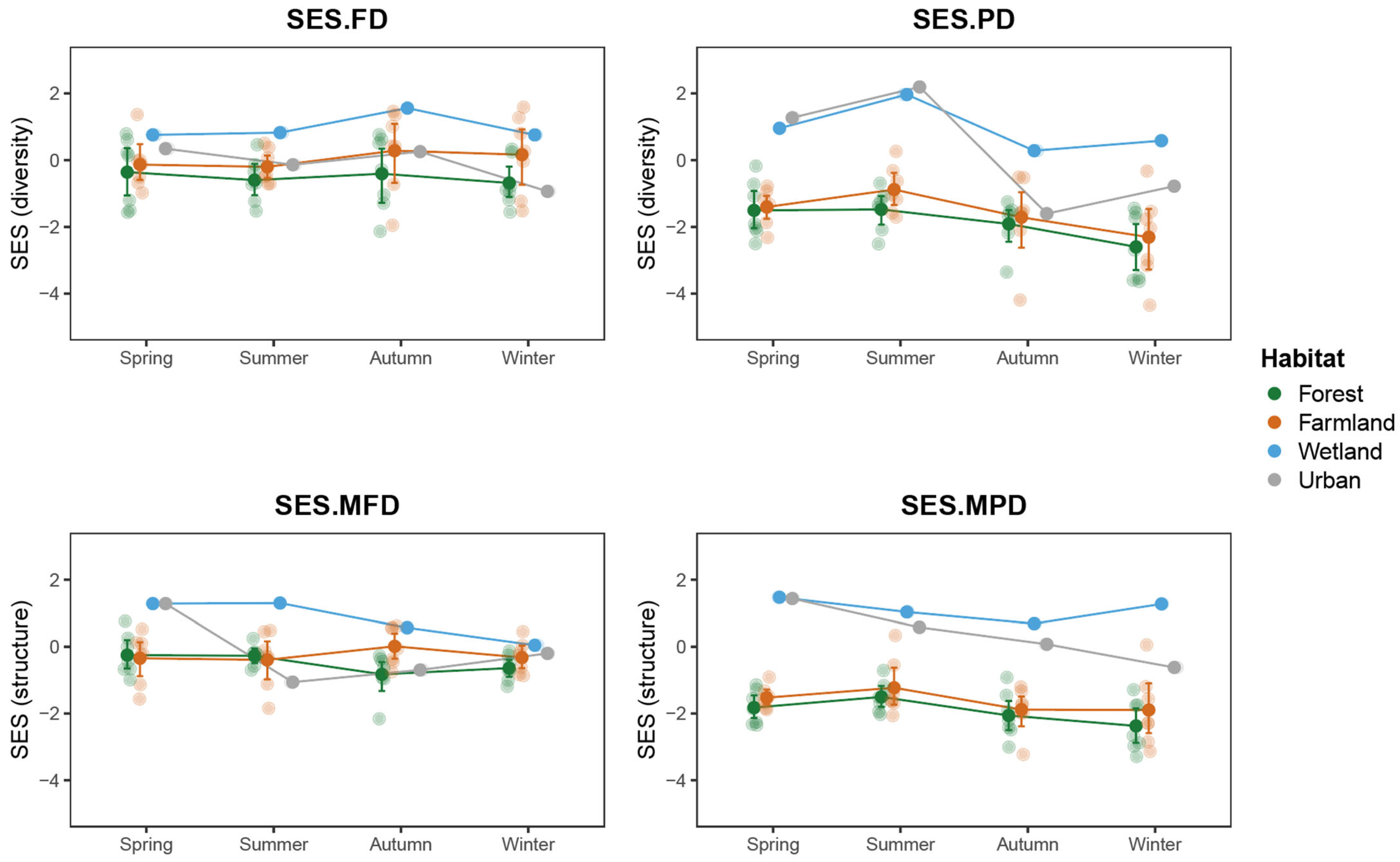

3.5. Community Assembly Analysis

3.6. Bird-Strike Risk Index Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Composition Characteristics of Bird Communities and Regional Ecological Context

4.2. Effects of Different Habitats on Avian Diversity

4.3. Seasonal Variation and Community Structure Dynamics

4.4. Patterns of Dominant Species and Ecological Adaptation

4.5. Bird-Strike Risk Index and Management Implications

- (1).

- Wetland and farmland zones—regularly remove standing water and tall grasses to reduce the attraction of wading birds.

- (2).

- Forest and urban edge zones—optimize vegetation structure to decrease nesting opportunities for edge-dependent species.

- (3).

- Airport core areas—implement dynamic deterrence measures, such as sound-light repellents, drone patrols, and time-segmented bird management to minimize aggregation risks.

4.6. Limitations and Future Prospects

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soldatini, C.; Georgalas, V.; Torricelli, P.; Albores-Barajas, Y.V. An Ecological Approach to Birdstrike Risk Analysis. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2010, 56, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyacı, E.; Altın, M. Experimental and Numerical Approach on Bird Strike: A Review. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2023, 7, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Swaddle, J.P.; Moseley, D.L.; Hinders, M.K.; Smith, E.P. A Sonic Net Excludes Birds from an Airfield: Implications for Reducing Bird Strike and Crop Losses. Ecol. Appl. 2016, 26, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, N.S. Perspectives in Ornithology: Competition in the Air: Birds versus Aircraft. Auk 2002, 119, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solman, V. Ecological Control of Bird Hazard to Aircraft. In Proceedings of the Bird Control Seminars Proceedings, Bowling Green, OH, Canada, 13–15 September 1966; Volume 230. [Google Scholar]

- Dolbeer, R.A. Introduction to Special Topic: Birds and Aircraft—Fighting for Airspace in Ever More Crowded Skies. Hum.–Wildl. Confl. 2009, 3, 165–166. [Google Scholar]

- Dolbeer, R.A. Trends in Reporting of Wildlife Strikes with Civil Aircraft and in Identification of Species Struck Under a Primarily Voluntary Reporting System, 1990–2013; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Viljoen, I.M.; Bouwman, H. Conflicting Traffic: Characterization of the Hazards of Birds Flying across an Airport Runway. Afr. J. Ecol. 2016, 54, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, R.F.; Buschke, F.T. Urbanization around an Airfield Alters Bird Community Composition, but Not the Hazard of Bird–Aircraft Collision. Environ. Conserv. 2019, 46, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N. A Decade of Change for the Israeli Air Force. In Proceedings of the Bird Strike Committee Proceedings, Niagara Falls, ON, Canada, 12–15 September 2011; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Dolbeer, R.A.; Begier, M.; Miller, P.; Weller, J.R.; Anderson, A.L. Wildlife Strikes to Civil Aircraft in the United States, 1990–2021; U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- DeVault, T.L.; Belant, J.L.; Blackwell, B.F.; Seamans, T.W. Airports Offer Unrealized Potential for Alternative Energy Production. Environ. Manag. 2012, 49, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd, E.A.; Saad, S.; Desoky, M. Strategies of Rodent Control Methods at Airports. Glob. J. Sci. Front. Res. C Biol. Sci. 2014, 14, 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y. Risk Assessment Model Based on Set Pair Analysis Applied to Airport Bird Strikes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, M.; Li, N.; Jiang, B.; Guo, Y. Bird strike on aeroengine fan blades: A combined experimental and numerical study. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2026, 168, 110955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallord, J.W.; Dolman, P.M.; Brown, A.F.; Sutherland, W.J. Linking Recreational Disturbance to Population Size in a Ground-Nesting Passerine. J. Appl. Ecol. 2007, 44, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conkling, T.J.; Belant, J.L.; DeVault, T.L.; Martin, J.A. Impacts of Biomass Production at Civil Airports on Grassland Bird Conservation and Aviation Strike Risk. Ecol. Appl. 2018, 28, 1168–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennell, C.G.; Popay, A.J.; Rolston, M.P.; Card, S.D.; Middleton, K.R. Avanex Unique Endophyte Technology: Reduced Insect Food Source at Airports. Environ. Entomol. 2016, 45, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglay, R.B.; Buckingham, B.N.; Seamans, T.W.; Martin, J.A.; Blackwell, B.F.; Belant, J.L.; DeVault, T.L. Bird Use of Grain Fields and Implications for Habitat Management at Airports. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 242, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alquezar, R.D.; Tolesano-Pascoli, G.; Gil, D.; Macedo, R.H. Avian Biotic Homogenization Driven by Airport-Affected Environments. Urban Ecosyst. 2020, 23, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, B.F.; Wright, S.E. Collisions of Red-Tailed Hawks (Buteo jamaicensis), Turkey Vultures (Cathartes aura), and Black Vultures (Coragyps atratus) with Aircraft: Implications for Bird Strike Reduction. J. Raptor Res. 2006, 40, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolbeer, R.A. Height Distribution of Birds Recorded by Collisions with Civil Aircraft. J. Wildl. Manag. 2006, 70, 1345–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, M.B.; Kougher, J.D.; DeVault, T.L. Civil Airports from a Landscape Perspective: A Multi-Scale Approach with Implications for Reducing Bird Strikes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 179, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, B.F.; DeVault, T.L.; Fernández-Juricic, E.; Dolbeer, R.A. Wildlife Collisions with Aircraft: A Missing Component of Land-Use Planning for Airports. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009, 93, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccon, F.; Zucchetta, M.; Bossi, G.; Borrotti, M.; Torricelli, P.; Franzoi, P. A Land-Use Perspective for Birdstrike Risk Assessment: The Attraction Risk Index. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, M.B.; Blackwell, B.F.; DeVault, T.L. Collective Effect of Landfills and Landscape Composition on Bird–Aircraft Collisions. Hum.–Wildl. Interact. 2020, 14, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, W.K.; Weston, M.A. The Assemblage of Birds Struck by Aircraft Differs among Nearby Airports in the Same Bioregion. Wildl. Res. 2021, 48, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVault, T.L.; Blackwell, B.F.; Seamans, T.W.; Belant, J.L. Identification of Off-Airport Interspecific Avian Hazards to Aircraft. J. Wildl. Manag. 2016, 80, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villéger, S.; Grenouillet, G.; Brosse, S. Decomposing Functional Beta-Diversity Reveals That Low Functional Beta-Diversity Is Driven by Low Functional Turnover in European Fish Assemblages. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2013, 22, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, X.; Baselga, A.; Ding, P. Functional and Phylogenetic Structure of Island Bird Communities. J. Anim. Ecol. 2017, 86, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, C.O.; Ackerly, D.D.; McPeek, M.A.; Donoghue, M.J. Phylogenies and Community Ecology. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2002, 33, 475–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavender-Bares, J.; Kozak, K.H.; Fine, P.V.A.; Kembel, S.W. The Merging of Community Ecology and Phylogenetic Biology. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 693–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meynard, C.N.; Devictor, V.; Mouillot, D.; Thuiller, W.; Jiguet, F.; Mouquet, N. Beyond Taxonomic Diversity Patterns: How Do Alpha, Beta and Gamma Components of Bird Functional and Phylogenetic Diversity Respond to Environmental Gradients across France. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2011, 20, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegen, J.C.; Hurlbert, A.H. Inferring Ecological Processes from Taxonomic, Phylogenetic and Functional Trait Beta-Diversity. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, B.C.; Gillespie, R.G. Phylogenetic Analysis of Community Assembly and Structure over Space and Time. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008, 23, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Feeley, K.J.; Wang, Y.; Pakeman, R.J.; Ding, P. Patterns of Bird Functional Diversity on Land-Bridge Island Fragments. J. Anim. Ecol. 2013, 82, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, D.F.B.; Gogol-Prokurat, M.; Nogeire, T.; Molinari, N.; Richers, B.T.; Lin, B.B.; Simpson, N.; Mayfield, M.M.; DeClerck, F. Loss of Functional Diversity under Land Use Intensification across Multiple Taxa. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X.; Chen, D.; Zhang, M.; Quan, Q.; Møller, A.P.; Zou, F. Seasonal Dynamics of Waterbird Assembly Mechanisms Revealed by Patterns in Phylogenetic and Functional Diversity in a Subtropical Wetland. Biotropica 2019, 51, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, R.D.; Cox, S.B.; Strauss, R.E.; Willig, M.R. Patterns of Functional Diversity across an Extensive Environmental Gradient: Vertebrate Consumers, Hidden Treatments and Latitudinal Trends. Ecol. Lett. 2003, 6, 1099–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, X.; Baselga, A.; Leprieur, F.; Song, Y.; Ding, P. Selective Extinction Drives Taxonomic and Functional Alpha and Beta Diversities in Island Bird Assemblages. J. Anim. Ecol. 2016, 85, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.H.; Zhu, Y.S. Discussion on the Integrated Development of Aviation and Tourism in Lincang. J. Jilin Radio TV Univ. 2018, 6, 148–149. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N. Study on the Karst Development Pattern and Foundation Stability of an Airport in Lincang, Yunnan; Chengdu University of Technology: Chengdu, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, G.; Wang, Z. Bird Survey at Lincang Airport, Yunnan. Wildlife 2006, 27, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, Z.W.; Ding, C.Q. Application of the Line Transect Method in Bird Population Surveys. Chin. J. Ecol. 2003, 22, 127–130. [Google Scholar]

- Bibby, C.J.; Burgess, N.D.; Hill, D.A.; Simon, M. Bird Census Techniques, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell, R.K.; Chang, M. Interpolating, Extrapolating, and Comparing Incidence-Based Species Accumulation Curves. Ecology 2004, 85, 2717–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, A.; Chazdon, R.L.; Colwell, R.K.; Shen, T.J. A New Statistical Approach for Assessing Compositional Similarity Based on Incidence and Abundance Data. Ecol. Lett. 2005, 8, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Friendly, M.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; McGlinn, D.; O’Hara, R.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 2.6-4. 2021. Available online: https://github.com/vegandevs/vegan (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Hsieh, T.C.; Ma, K.H.; Chao, A. iNEXT: An R package for rarefaction and extrapolation of species diversity (Hill numbers). Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, J.; Bakewell, D.; Bureau, A.W. Shorebird Studies Manual; Asian Wetland Bureau: Kuala Lumpur, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Petchey, O.L.; Gaston, K.J. Functional Diversity (FD), Species Richness and Community Composition. Ecol. Lett. 2002, 5, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laliberté, E.; Legendre, P.; Shipley, B. FD: Measuring Functional Diversity from Multiple Traits, and Other Tools for Functional Ecology. R Package Version 1.0-12.3. 2014. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=FD (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Kembel, S.W.; Cowan, P.D.; Helmus, M.R.; Cornwell, W.K.; Morlon, H.; Ackerly, D.D.; Blomberg, S.P.; Webb, C.O. Picante: R Tools for Integrating Phylogenies and Ecology. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 1463–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faith, D.P. Conservation Evaluation and Phylogenetic Diversity. Biol. Conserv. 1992, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetz, W.; Thomas, G.H.; Joy, J.B.; Hartmann, K.; Mooers, A.O. The Global Diversity of Birds in Space and Time. Nature 2012, 491, 444–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, A.J.; Rambaut, A. BEAST: Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis by Sampling Trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007, 7, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.J.; Li, D.L.; Wan, D.M.; Yin, J.X.; Zhang, L. Bird Diversity and Bird Strike Prevention at Shenyang Taoxian International Airport. J. Ecol. 2015, 34, 2561–2567. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, W.; Tang, J.; Duan, Y. Breeding-Season Bird Diversity in Yongde County, Yunnan Province. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 2021, 37, 1423–1429. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Liu, S.; Geng, J.; Luo, X.; Duan, Y. Bird Diversity and Vertical Distribution of Breeding Birds in Yuanyang County, Yunnan Province. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 2024, 40, 1213–1221. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Wang, G.S.; Zhang, X.L.; Zhang, Y.L.; Luo, X. Bird Diversity and Bird-Strike Risk Assessment at Wenshan Wa Mountain Airport, Cangyuan, Yunnan. Sichuan J. Zool. 2021, 40, 568–580. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.; Hong, L.; Wang, Y.Y.; Li, Q.; Hu, Y.; Luo, X. Bird Diversity and Bird-Strike Prevention at Dali Airport, Yunnan. West. For. Sci. 2022, 51, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cadotte, M.W.; Tucker, C.M. Should Environmental Filtering Be Abandoned? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2017, 32, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarzyna, M.A.; Quintero, I.; Jetz, W. Global Functional and Phylogenetic Structure of Avian Assemblages across Elevation and Latitude. Ecol. Lett. 2021, 24, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Luo, K.; Brown, C.; Lin, L. A Taxonomic, Functional, and Phylogenetic Perspective on the Community Assembly of Passerine Birds along an Elevational Gradient in Southwest China. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 2712–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouillot, D.; Graham, N.A.J.; Villéger, S.; Mason, N.W.H.; Bellwood, D.R. A Functional Approach Reveals Community Responses to Disturbances. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2013, 28, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Abundance | Coverage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| urban | 32 | 269 | 0.9629 |

| farmland | 94 | 1951 | 0.9928 |

| forest | 103 | 2249 | 0.9929 |

| wetland | 39 | 390 | 0.9693 |

| autumn | 86 | 1329 | 0.9895 |

| spring | 81 | 1048 | 0.9895 |

| summer | 88 | 985 | 0.9797 |

| winter | 84 | 1497 | 0.992 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Liu, P.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Duan, Y. Bird Diversity and Bird-Strike Risk at Lincang Boshang Airport. Animals 2025, 15, 3250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223250

Liu J, Liu P, Li J, Zhang J, Duan Y. Bird Diversity and Bird-Strike Risk at Lincang Boshang Airport. Animals. 2025; 15(22):3250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223250

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jun, Peng Liu, Jia Li, Jiansong Zhang, and Yubao Duan. 2025. "Bird Diversity and Bird-Strike Risk at Lincang Boshang Airport" Animals 15, no. 22: 3250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223250

APA StyleLiu, J., Liu, P., Li, J., Zhang, J., & Duan, Y. (2025). Bird Diversity and Bird-Strike Risk at Lincang Boshang Airport. Animals, 15(22), 3250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223250