Research Methods for the Analysis of Visual Emotion Cues in Animals: A Workshop Report

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. The Research Methods for Animal Emotion Analysis (RM4AEA) Workshop

2. Methods to Measure Emotion Correlates in Animals and Its Applications

3. From Behavioural Emotion Correlates to Emotion Indicators

3.1. Issues When Identifying Behavioural Emotion Correlates

3.2. Measuring Behavioural Emotion Correlates

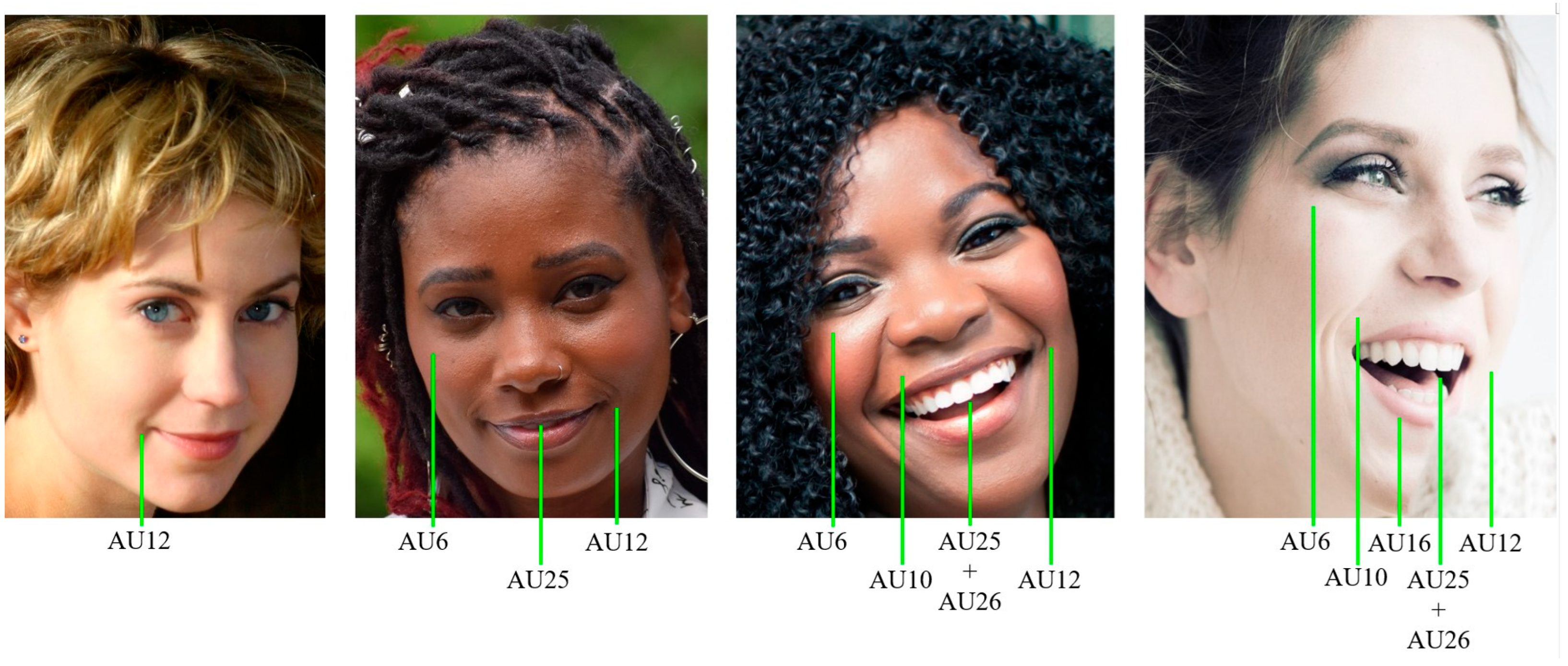

3.2.1. Facial Expressions

3.2.2. Bodily Expressions

3.2.3. Asymmetric Visual Behaviours

4. Main Challenges in Data Collection for Measuring Animal Emotions

- Observer biases: The efficient and adaptive functions of the human brain are supported by a vast collection of such biases [60,61], which may be particularly challenging to control in emotion studies. Most of these biases affect information process at an unconscious level, in which individuals automatically appraise an observation based on past experiences, background, knowledge, and other intrinsic (e.g., mood) or extrinsic (e.g., environment) factors. Biases may influence different stages of information processing, including how we select, define, classify, and/or interpret information [60]. Common examples in animal behaviour include biases of interpretation, such as anthropocentrism, which affects the interpretation of observations by framing them uniquely from a human point of view [62]. Other biases occur at an early perceptual level and may affect selection of information, such as attentional blindness, which concentrates attention on specific aspects of an observation and filters out more salient changes [63]. We provide a list of these common biases, with practical examples from animal behaviour studies, and mitigation strategies in Table S3.

- Small sample sizes: Using small sample sizes leads to studies with insufficient statistical power [64,65]. Yet, it is not uncommon to publish human and ape studies with sample sizes of just a couple of participants (e.g., one individual [66]); if studies are larger, sample sizes are rarely more than 30 individuals, even in easily accessible species/populations (e.g., dogs, horses, university undergraduates [67,68,69]). These usually do not allow generalisations to entire populations or species, often contributing to the problem of unrepresentative human WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, and Democratic) or animal STRANGE (Sociability, Trappability, Rearing history, Acclimation and habituation, Natural changes in responsiveness, Genetic make-up, and Experience) samples [70,71,72] (Table S3). There are obviously some cases where these limited samples are the only ones possible to obtain (e.g., from threatened species with small populations or difficult access). It is also not uncommon for visual stimuli to feature only one or few individuals (e.g., [73]) in species that are very diverse morphologically, behaviourally, and genetically (as is the case of dogs and humans). Whilst some cognitive processes may vary little between individuals (e.g., eye movements), emotion processes are still not well understood regarding individual variation, and hence, larger and more representative samples are surely needed. Large-scale multi-laboratory collaborations, such as ManyPrimates [74], ManyDogs [75], or ManyFaces [76], may be one solution for this issue.

- Differences between humans and other animals: Animal emotion research cannot rely on self-report for validation or triangulation of collected data, and must instead rely on other variables. In addition, whilst humans typically participate in research studies without habituation or rewards (e.g., voucher), animals usually require these, which vary depending on species and individual. When testing individuals living in groups (e.g., primates), it is common for some individuals to be motivated to participate, but they are prevented from doing so by other group members who monopolise research participation, which is usually linked to hierarchical status. These limitations not only reduce sample sizes, but may also introduce biases in data sets, for example, when only food-motivated or high-ranking individuals participate in studies.

- Ethical issues when producing data sets: This is a larger debate than we can cover here in this article, but as this was mentioned by the workshop panel discussion (Table S2), we briefly give an overview of some of the ethical issues. When creating data sets, in particular for negative emotions, data is either collected in naturalistic situations (e.g., veterinary interventions), selected from public databases (e.g., YouTube), or the responses are induced experimentally to create a data set. In this latter scenario, ethical considerations and even legal frameworks vary widely between countries or research groups within the same country. Some researchers may consider it ethical to apply a variety of negative stimuli (from mild ones, such as opening an umbrella as a fear stimulus, to stronger ones such as injecting a painful agent) to create data sets (e.g., video or audio recordings), while others will disagree. Whilst the induction of negative emotions in human experiments is based on informed consent, in animals the informed consent is given by the humans managing the animals (since, obviously, animals cannot give consent). On the other hand, if the stimulus applied and consequently the response is too mild, AI systems may perform poorly. Furthermore, in some situations, there might be cognitive dissonance within ethical decisions. For example, farm animals may suffer and die in factory farming under poor welfare conditions, but a study applying mild pain to the same individuals (with the potential to deepen the knowledge about how pain is produced and can be detected in those species, hence being beneficial for them in the long term) would be considered unethical.

- Excessive focus on facial cues: Perhaps due to human-centric social interactions being based more on the face than the body [77,78,79], there is often an excessive focus on facial expressions and their association with positive or negative situations also in animals. This can lead to circular outcomes to some extent (see [80] for more discussion on this issue), but more importantly may result in researchers missing the more relevant cues for other species, whose social interactions may focus less on faces and more on bodies (e.g., dogs [81] or primates [82]).

5. Biases Introduced by Researchers When Interpreting Data Sets with Animal Behaviour

6. The Role of AI in Measuring Animal Emotion

7. Future Directions on Research Methods for the Analysis of Visual Cues in Animal Emotion and Communication

- New AnimalFACS and AnimalBAPS: AnimalFACS and AnimalBAPS for other species are currently being developed and during the RM4AEA workshop, participants reported additional interest in developing these tools for other species (e.g., rodents and farm animals due to welfare concerns). This will advance the knowledge of emotion not only in animals but as a concept in human evolution.

- AnimalFACS and AnimalBAPS automation: The growing interest in these tools increases the need for automation of these very time-consuming tasks of coding behaviour. Large parts of research budgets are allocated towards behaviour training and coding, which automation could decrease (as we heard in Zamansky’s and Broome’s talks—Table S1). This goal can only be accomplished with large and good quality data sets, so the first steps to solve this issue would be to address the ethical considerations of these data sets (see Supplementary Materials).

- Rethinking data sets: In the different talks of the workshop on AI tools, the speakers (Table S1) suggested potential solutions for most of the issues described in Supplementary Materials, namely increasing data set size (requiring increased collaboration between AI and behaviour researchers), domain transfer (which may increase accuracy rate in some cases), and opting for an unsupervised approach (but using observation tools such as FACS post-analysis for explanatory value, e.g., [44], Figure 4). Since the judgement of another individual’s emotion is extremely difficult and subjective (even by trained experts), we argue that a more agnostic approach is needed. For example, the successful MaqFACS automation for the detection of macaque facial emotion cues [95] or the MacaquePose data set (from Matsumoto’s talk—Table S1 and [55], Figure 3) developed with DLC [92].

- Ground truth for animal emotion detection: There are two ways to establish this, as reported in several of the workshop talks (Table S1): (1) designing or scheduling the experimental setup to induce a particular emotion and (2) using labels provided by human experts. Whilst approach (1) may raise ethical concerns when examining negative emotions, approach (2) may lead to the introduction of varied biases (Table S3). For approach (1), collaboration between researchers is essential, as animals often need to undergo negative situations for veterinary procedures, and hence video recording these may create rich databases for AI. For approach (2), the same solutions as suggested above also apply here, e.g., strict reliability assessments and quality control of data labelling at different stages of an AI automation project.

- Interdisciplinary exchange: One obvious solution to the challenges presented in Supplementary Materials is to foster interdisciplinary collaborations across disciplines, including computer science, psychology, veterinary sciences, animal behaviour, philosophy, ethics, and law. Several of the workshop’s panellists (Table S2) mentioned the need for a forum to facilitate the exchange of ideas, knowledge, and data sets. Hence, we created a Discord server with the recordings of the workshop, where researchers and students interested in the workshop topics could join during and after the workshop. Finally, more funding needs to be geared towards multidisciplinary projects and global consortiums for setting baseline standards. Such multidisciplinary work may include reviews, white papers, reports, etc., gathered from experts in the different areas. The current workshop report stands as an example of this kind of multidisciplinary work, which we hope will generate debate, constructive criticism, and further ideas on how to expand the collaboration of the varied fields intersecting animal behaviour and AI.

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Damasio, A. Fundamental Feelings. Nature 2001, 413, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissy, A.; Manteuffel, G.; Jensen, M.B.; Moe, R.O.; Spruijt, B.; Keeling, L.J.; Winckler, C.; Forkman, B.; Dimitrov, I.; Langbein, J.; et al. Assessment of Positive Emotions in Animals to Improve Their Welfare. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 375–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corke, M.J. Indicators of Pain. In Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 147–152. ISBN 978-0-12-813252-4. [Google Scholar]

- Broom, D.M.; Johnson, K.G. Stress and Animal Welfare; Springer Science & Business Media: Heidelberg, Germany, 1993; ISBN 978-0-412-39580-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mendl, M.; Burman, O.H.P.; Parker, R.M.A.; Paul, E.S. Cognitive Bias as an Indicator of Animal Emotion and Welfare: Emerging Evidence and Underlying Mechanisms. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 118, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descovich, K.; Richmond, S.E.; Leach, M.C.; Buchanan-Smith, H.M.; Flecknell, P.; Farningham, D.A.H.; Witham, C.; Gates, M.C.; Vick, S.-J. Opportunities for Refinement in Neuroscience: Indicators of Wellness and Post-Operative Pain in Laboratory Macaques. Altex 2019, 36, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leconstant, C.; Spitz, E. Integrative Model of Human-Animal Interactions: A One Health-One Welfare Systemic Approach to Studying HAI. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 656833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caeiro, C.; Guo, K.; Mills, D. Dogs and Humans Respond to Emotionally Competent Stimuli by Producing Different Facial Actions. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiak, K.L.; Maul, D.; French, E.; Hellyer, P.W.; Vandewoude, S. Species-Specific Assessment of Pain in Laboratory Animals. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2003, 42, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone, L. Do “Prey Species” Hide Their Pain? Implications for Ethical Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. J. Appl. Anim. Ethics Res. 2020, 2, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tami, G.; Gallagher, A. Description of the Behaviour of Domestic Dog (Canis familiaris) by Experienced and Inexperienced People. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 120, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, A.H.; Lohmueller, K.E.; Wayne, R.K. Evolutionary History, Selective Sweeps, and Deleterious Variation in the Dog. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2016, 47, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, V.A.; Huntingford, F.; van den Bos, R. Variation in Emotion and Cognition Among Fishes. J. Agric. Env. Ethics 2013, 26, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittka, L.; Rossi, N. Social Cognition in Insects. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2022, 26, 578–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolls, E.T. Emotion and Decision-Making Explained; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-0-19-163515-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bremhorst, A.; Sutter, N.A.; Würbel, H.; Mills, D.S.; Riemer, S. Differences in Facial Expressions during Positive Anticipation and Frustration in Dogs Awaiting a Reward. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremhorst, A.; Mills, D.S.; Würbel, H.; Riemer, S. Evaluating the Accuracy of Facial Expressions as Emotion Indicators across Contexts in Dogs. Anim. Cogn. 2021, 25, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, L.F.; Adolphs, R.; Marsella, S.; Martinez, A.; Pollak, S.D. Emotional Expressions Reconsidered: Challenges to Inferring Emotion from Human Facial Movements. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2019, 20, 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P. An Argument for Basic Emotions. Cogn. Emot. 1992, 6, 169–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintze, S.; Smith, S.; Patt, A.; Bachmann, I.; Würbel, H. Are Eyes a Mirror of the Soul? What Eye Wrinkles Reveal about a Horse’s Emotional State. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, A. Emometer. Department of Life Sciences, University of Lincoln: Lincoln, UK, 2021; unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Burrows, A.M. Functional Morphology of Mimetic Musculature in Primates: How Social Variables and Body Size Stack up to Phylogeny. Anat. Rec. 2018, 301, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwin, C. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals; D. Appleton and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1896. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P. Universal Facial Expressions in Emotion. Stud. Psychol. 1973, 15, 140–147. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, D.; Hwang, H.S.; Yamada, H. Cultural Differences in the Relative Contributions of Face and Context to Judgments of Emotions. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2012, 43, 198–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, R.E.; Garrod, O.G.B.; Yu, H.; Caldara, R.; Schyns, P.G. Facial Expressions of Emotion Are Not Culturally Universal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 7241–7244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descovich, K.; Wathan, J.W.; Leach, M.C.; Buchanan-Smith, H.M.; Flecknell, P.; Farningham, D.; Vick, S.-J. Facial Expression: An under-Utilized Tool for the Assessment of Welfare in Mammals. ALTEX Altern. Anim. Exp. 2017, 34, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. Facial Coding Action System (FACS): A Technique for the Measurement of Facial Actions; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V.; Hager, J.C. Facial Action Coding System (FACS): Manual; Research Nexus: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vick, S.J.; Waller, B.M.; Parr, L.A.; Pasqualini, M.C.S.; Bard, K.A. A Cross-Species Comparison of Facial Morphology and Movement in Humans and Chimpanzees Using the Facial Action Coding System (FACS). J. Nonverbal Behav. 2007, 31, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia-Caeiro, C.; Kuchenbuch, P.H.; Oña, L.S.; Wegdell, F.; Leroux, M.; Schuele, A.; Taglialatela, J.; Townsend, S.; Surbeck, M.; Waller, B.M.; et al. Adapting the Facial Action Coding System for Chimpanzees (Pan Troglodytes) to Bonobos (Pan Paniscus): The ChimpFACS Extension for Bonobos. PeerJ 2025, 13, e19484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia-Caeiro, C.; Costa, R.; Hayashi, M.; Burrows, A.; Pater, J.; Miyabe-Nishiwaki, T.; Richardson, J.L.; Robbins, M.M.; Waller, B.; Liebal, K. GorillaFACS: The Facial Action Coding System for the Gorilla spp. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0308790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia-Caeiro, C.; Waller, B.M.; Zimmermann, E.; Burrows, A.M.; Davila-Ross, M. OrangFACS: A Muscle-Based Facial Movement Coding System for Orangutans (Pongo spp.). Int. J. Primatol. 2013, 34, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, B.M.; Lembeck, M.; Kuchenbuch, P.; Burrows, A.M.; Liebal, K. GibbonFACS: A Muscle-Based Facial Movement Coding System for Hylobatids. Int. J. Primatol. 2012, 33, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, L.A.; Waller, B.M.; Burrows, A.M.; Gothard, K.M.; Vick, S.J. Brief Communication: MaqFACS: A Muscle-Based Facial Movement Coding System for the Rhesus Macaque. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2010, 143, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia-Caeiro, C.; Holmes, K.; Miyabe-Nishiwaki, T. Extending the MaqFACS to Measure Facial Movement in Japanese Macaques (Macaca Fuscata) Reveals a Wide Repertoire Potential. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julle-Danière, É.; Micheletta, J.; Whitehouse, J.; Joly, M.; Gass, C.; Burrows, A.M.; Waller, B.M. MaqFACS (Macaque Facial Action Coding System) Can Be Used to Document Facial Movements in Barbary Macaques (Macaca Sylvanus). PeerJ 2015, 3, e1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, P.R.; Waller, B.M.; Burrows, A.M.; Julle-Danière, E.; Agil, M.; Engelhardt, A.; Micheletta, J. Morphological Variants of Silent Bared-Teeth Displays Have Different Social Interaction Outcomes in Crested Macaques (Macaca Nigra). Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2020, 173, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia-Caeiro, C.; Burrows, A.; Wilson, D.A.; Abdelrahman, A.; Miyabe-Nishiwaki, T. CalliFACS: The Common Marmoset Facial Action Coding System. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia-Caeiro, C.; Burrows, A.M.; Waller, B.M. Development and Application of CatFACS: Are Human Cat Adopters Influenced by Cat Facial Expressions? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 189, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, B.M.; Peirce, K.; Correia-Caeiro, C.; Scheider, L.; Burrows, A.M.; McCune, S.; Kaminski, J. Paedomorphic Facial Expressions Give Dogs a Selective Advantage. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wathan, J.; Burrows, A.M.; Waller, B.M.; McComb, K. EquiFACS: The Equine Facial Action Coding System. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.; Silventoinen, A.; Gleerup, K.B.; Andersen, P.H. Equine Facial Action Coding System for Determination of Pain-Related Facial Responses in Videos of Horses. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, P.H.; Broomé, S.; Rashid, M.; Lundblad, J.; Ask, K.; Li, Z.; Hernlund, E.; Rhodin, M.; Kjellström, H. Towards Machine Recognition of Facial Expressions of Pain in Horses. Animals 2021, 11, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florkiewicz, B.N. Navigating the Nuances of Studying Animal Facial Behaviors with Facial Action Coding Systems. Front. Ethol. 2025, 4, 1686756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dael, N.; Mortillaro, M.; Scherer, K. The Body Action and Posture Coding System (BAP): Development and Reliability. J. Nonverbal Behav. 2012, 36, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, D.; Keeling, L.J. Routine Activities and Emotion in the Life of Dairy Cows: Integrating Body Language into an Affective State Framework. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groffen, J. Tail Posture and Motion as a Possible Indicator of Emotional State in Pigs. Available online: https://stud.epsilon.slu.se/4692/ (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Camerlink, I.; Coulange, E.; Farish, M.; Baxter, E.M.; Turner, S.P. Facial Expression as a Potential Measure of Both Intent and Emotion. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reefmann, N.; Bütikofer Kaszàs, F.; Wechsler, B.; Gygax, L. Physiological Expression of Emotional Reactions in Sheep. Physiol. Behav. 2009, 98, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siniscalchi, M.; Lusito, R.; Vallortigara, G.; Quaranta, A. Seeing Left- or Right-Asymmetric Tail Wagging Produces Different Emotional Responses in Dogs. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 2279–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGowan, R.T.S.; Rehn, T.; Norling, Y.; Keeling, L.J. Positive Affect and Learning: Exploring the “Eureka Effect” in Dogs. Anim. Cogn. 2014, 17, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fureix, C.; Hausberger, M.; Seneque, E.; Morisset, S.; Baylac, M.; Cornette, R.; Biquand, V.; Deleporte, P. Geometric Morphometrics as a Tool for Improving the Comparative Study of Behavioural Postures. Naturwissenschaften 2011, 98, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, A.; Dael, N.; Caeiro, C.; Würbel, H.; Mills, D.S.; Riemer, S. From BAP to DogBAP–Adapting a Human Body Movement Coding System for Use in Dogs. In Proceedings of the Measuring Behaviour: 11th International Conference on Methods and Techniques in Behavioral Research, Manchester, UK, 5–8 June 2018; Grant, R.A., Allen, T., Spink, A., Sullivan, M., Eds.; Manchester Metropolitan University: Manchester, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-910029-39-8. [Google Scholar]

- Labuguen, R.; Matsumoto, J.; Negrete, S.B.; Nishimaru, H.; Nishijo, H.; Takada, M.; Go, Y.; Inoue, K.; Shibata, T. MacaquePose: A Novel “In the Wild” Macaque Monkey Pose Dataset for Markerless Motion Capture. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 581154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, T.; Guo, K.; Frasnelli, E.; Wilkinson, A.; Mills, D.S. Testing of Behavioural Asymmetries as Markers for Brain Lateralization of Emotional States in Pet Dogs: A Critical Review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 143, 104950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goursot, C.; Düpjan, S.; Puppe, B.; Leliveld, L.M.C. Affective Styles and Emotional Lateralization: A Promising Framework for Animal Welfare Research. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 237, 105279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlinghieri, F.; Panizzon, P.; Penry-Williams, I.L.; Brown, C. Laterality and Fish Welfare—A Review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 236, 105239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasnelli, E. Lateralization in Invertebrates. In Lateralized Brain Functions: Methods in Human and Non-Human Species; Rogers, L.J., Vallortigara, G., Eds.; Neuromethods; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 153–208. ISBN 978-1-4939-6725-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tuyttens, F.A.M.; de Graaf, S.; Heerkens, J.L.T.; Jacobs, L.; Nalon, E.; Ott, S.; Stadig, L.; Van Laer, E.; Ampe, B. Observer Bias in Animal Behaviour Research: Can We Believe What We Score, If We Score What We Believe? Anim. Behav. 2014, 90, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbrizzi, S.; Papadopoulos, S.; Ntoutsi, E.; Kompatsiaris, I. A Survey on Bias in Visual Datasets. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2022, 223, 103552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, J.; Casey, R. Anthropomorphism and Anthropocentrism as Influences in the Quality of Life of Companion Animals. Anim. Welf. 2007, 16, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, A. Inattentional Blindness: Looking Without Seeing. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2003, 12, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.H.; Vilidaite, G.; Lygo, F.A.; Smith, A.K.; Flack, T.R.; Gouws, A.D.; Andrews, T.J. Power Contours: Optimising Sample Size and Precision in Experimental Psychology and Human Neuroscience. Psychol. Methods 2021, 26, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.F.; Kelley, K.; Maxwell, S.E. Sample-Size Planning for More Accurate Statistical Power: A Method Adjusting Sample Effect Sizes for Publication Bias and Uncertainty. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 28, 1547–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, C.M.; Menzel, C.R. Dissociation of Cortisol and Behavioral Indicators of Stress in an Orangutan (Pongo Pygmaeus) during a Computerized Task. Primates 2001, 42, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Li, Z.; Yan, Y.; Li, W. Viewing Heterospecific Facial Expressions: An Eye-Tracking Study of Human and Monkey Viewers. Exp. Brain Res. 2019, 237, 2045–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia-Caeiro, C.; Guo, K.; Mills, D.S. Perception of Dynamic Facial Expressions of Emotion between Dogs and Humans. Anim. Cogn. 2020, 23, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vehlen, A.; Spenthof, I.; Tönsing, D.; Heinrichs, M.; Domes, G. Evaluation of an Eye Tracking Setup for Studying Visual Attention in Face-to-Face Conversations. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, J.; Heine, S.J.; Norenzayan, A. Beyond WEIRD: Towards a Broad-Based Behavioral Science. Behav. Brain Sci. 2010, 33, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, M.M.; Rutz, C. How STRANGE Are Your Study Animals? Nature 2020, 582, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apicella, C.; Norenzayan, A.; Henrich, J. Beyond WEIRD: A Review of the Last Decade and a Look Ahead to the Global Laboratory of the Future. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2020, 41, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinaro, H.G.; Wynne, C.D.L. Barking Up the Wrong Tree: Human Perception of Dog Emotions Is Influenced by Extraneous Factors. Anthrozoös 2025, 38, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguenounon, G.S.; Ballesta, S.; Beaud, A.; Bustamante, L.; Canteloup, C.; Joly, M.; Loyant, L.; Meunier, H.; Roig, A.; Troisi, C.A.; et al. ManyPrimates: An Infrastructure for International Collaboration in Research in Primate Cognition. Rev. De. Primatol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberghina, D.; Bray, E.E.; Buchsbaum, D.; Byosiere, S.-E.; Espinosa, J.; Gnanadesikan, G.E.; Alexandrina Guran, C.-N.; Hare, E.; Horschler, D.J.; Huber, L.; et al. ManyDogs Project: A Big Team Science Approach to Investigating Canine Behavior and Cognition. Comp. Cogn. Behav. Rev. 2023, 18, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, N.A.; DeBruine, L.M.; Azevedo, F.; Baumgartner, H.A.; Frank, M.C. ‘Big Team’ Science Challenges Us to Reconsider Authorship. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2023, 7, 665–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelder, B. Towards the Neurobiology of Emotional Body Language. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelder, B. Why Bodies? Twelve Reasons for Including Bodily Expressions in Affective Neuroscience. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 3475–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kret, M.E.; Stekelenburg, J.J.; Roelofs, K.; Gelder, B. Perception of Face and Body Expressions Using Electromyography, Pupillometry and Gaze Measures. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia-Caeiro, C.; Guo, K.; Mills, D.S. Visual Perception of Emotion Cues in Dogs: A Critical Review of Methodologies. Anim. Cogn. 2023, 26, 727–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia-Caeiro, C.; Guo, K.; Mills, D. Bodily Emotional Expressions Are a Primary Source of Information for Dogs, but Not for Humans. Anim. Cogn. 2021, 24, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kano, F.; Tomonaga, M. Attention to Emotional Scenes Including Whole-Body Expressions in Chimpanzees (Pan Troglodytes). J. Comp. Psychol. 2010, 124, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burghardt, G.M.; Bartmess-LeVasseur, J.N.; Browning, S.A.; Morrison, K.E.; Stec, C.L.; Zachau, C.E.; Freeberg, T.M. Perspectives—Minimizing Observer Bias in Behavioral Studies: A Review and Recommendations. Ethology 2012, 118, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, A. Disambiguating the “Guilty Look”: Salient Prompts to a Familiar Dog Behaviour. Behav. Process. 2009, 81, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, M.; Matuszek, C.; Munson, S.A. Unequal Representation and Gender Stereotypes in Image Search Results for Occupations. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 18–23 April 2015; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 3819–3828. [Google Scholar]

- Hagendorff, T.; Bossert, L.N.; Tse, Y.F.; Singer, P. Speciesist Bias in AI: How AI Applications Perpetuate Discrimination and Unfair Outcomes against Animals. AI Ethics 2023, 3, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feighelstein, M.; Ehrlich, Y.; Naftaly, L.; Alpin, M.; Nadir, S.; Shimshoni, I.; Pinho, R.H.; Luna, S.P.L.; Zamansky, A. Deep Learning for Video-Based Automated Pain Recognition in Rabbits. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Deng, W. Deep Facial Expression Recognition: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2022, 13, 1195–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noroozi, F.; Corneanu, C.A.; Kamińska, D.; Sapiński, T.; Escalera, S.; Anbarjafari, G. Survey on Emotional Body Gesture Recognition. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2021, 12, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Dhall, A. A Survey on Automatic Multimodal Emotion Recognition in the Wild. In Advances in Data Science: Methodologies and Applications; Phillips-Wren, G., Esposito, A., Jain, L.C., Eds.; Intelligent Systems Reference Library; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 35–64. ISBN 978-3-030-51870-7. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Eidan, R.; Al-Khalifa, H.; Al-Salman, A. Deep-Learning-Based Models for Pain Recognition: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, A.; Mamidanna, P.; Cury, K.M.; Abe, T.; Murthy, V.N.; Mathis, M.W.; Bethge, M. DeepLabCut: Markerless Pose Estimation of User-Defined Body Parts with Deep Learning. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltshire, C.; Lewis-Cheetham, J.; Komedová, V.; Matsuzawa, T.; Graham, K.E.; Hobaiter, C. DeepWild: Application of the Pose Estimation Tool DeepLabCut for Behaviour Tracking in Wild Chimpanzees and Bonobos. J. Anim. Ecol. 2023, 92, 1560–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broome, S.; Feighelstein, M.; Zamansky, A.; Carreira Lencioni, G.; Haubro Andersen, P.; Pessanha, F.; Mahmoud, M.; Kjellström, H.; Salah, A.A. Going deeper than tracking: A survey of computer-vision based recognition of animal pain and emotions. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2023, 131, 572–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, A.; Parr, L.A.; Gothard, K.; Paz, R.; Pryluk, R. Automatic Recognition of Macaque Facial Expressions for Detection of Affective States. eNeuro 2021, 8, ENEURO.0117-21.2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, T.; Frasnelli, E.; Guo, K.; Barber, A.; Wilkinson, A.; Mills, D.S. Is There an Association between Paw Preference and Emotionality in Pet Dogs? Animals 2022, 12, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adolphs, R.; Mlodinow, L.; Barrett, L.F. What Is an Emotion? Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R1060–R1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L. Solving the Emotion Paradox: Categorization and the Experience of Emotion. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 20–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P. What Scientists Who Study Emotion Agree About. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 11, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kret, M.E.; Massen, J.J.M.; de Waal, F.B.M. My Fear Is Not, and Never Will Be, Your Fear: On Emotions and Feelings in Animals. Affect. Sci. 2022, 3, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, B.M.; Micheletta, J. Facial Expression in Nonhuman Animals. Emot. Rev. 2013, 5, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasio, A. Neural Basis of Emotions. Scholarpedia 2011, 6, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolphs, R. The Biology of Fear. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, R79–R93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panksepp, J. The Basic Emotional Circuits of Mammalian Brains: Do Animals Have Affective Lives? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011, 35, 1791–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, K. What Are Emotions? And How Can They Be Measured? Soc. Sci. Inf. 2005, 44, 695–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, P.F.; Prichard, A.; Spivak, M.; Berns, G.S. Awake Canine fMRI Predicts Dogs’ Preference for Praise vs Food. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2016, 11, 1853–1862. [Google Scholar]

- Karl, S.; Boch, M.; Virányi, Z.; Lamm, C.; Huber, L. Training Pet Dogs for Eye-Tracking and Awake fMRI. Behav. Res. 2020, 52, 838–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karl, S.; Boch, M.; Zamansky, A.; van der Linden, D.; Wagner, I.C.; Völter, C.J.; Lamm, C.; Huber, L. Exploring the Dog–Human Relationship by Combining fMRI, Eye-Tracking and Behavioural Measures. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 22273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karl, S.; Sladky, R.; Lamm, C.; Huber, L. Neural Responses of Pet Dogs Witnessing Their Caregiver’s Positive Interactions with a Conspecific: An fMRI Study. Cereb. Cortex Commun. 2021, 2, tgab047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, A.L.A.; Muller, E.M.; Randi, D.; Muller, C.; Huber, L. Heart Rate Changes in Pet and Lab Dogs as Response to Human Facial Expressions. J. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2017, 31, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, M.; Kubo, T.; Mogi, K.; Ikeda, K.; Nagasawa, M.; Kikusui, T. Heart Rate Variability Predicts the Emotional State in Dogs. Behav. Process. 2016, 128, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ash, H.; Smith, T.E.; Knight, S.; Buchanan-Smith, H.M. Measuring Physiological Stress in the Common Marmoset (Callithrix jacchus): Validation of a Salivary Cortisol Collection and Assay Technique. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 185, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmelíková, E.; Bolechová, P.; Chaloupková, H.; Svobodová, I.; Jovičić, M.; Sedmíková, M. Salivary Cortisol as a Marker of Acute Stress in Dogs: A Review. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2020, 72, 106428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebal, K.; Pika, S.; Tomasello, M. Gestural Communication of Orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus). Gesture 2006, 6, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascelles, B.D.X.; Hansen, B.D.; Thomson, A.; Pierce, C.C.; Boland, E.; Smith, E.S. Evaluation of a Digitally Integrated Accelerometer-Based Activity Monitor for the Measurement of Activity in Cats. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2008, 35, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ask, K.; Andersen, P.H.; Tamminen, L.-M.; Rhodin, M.; Hernlund, E. Performance of Four Equine Pain Scales and Their Association to Movement Asymmetry in Horses with Induced Orthopedic Pain. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 938022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, M.S. Observing Animal Behaviour: Design and Analysis of Quantitative Data; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-0-19-856935-0. [Google Scholar]

- Boneh-Shitrit, T.; Feighelstein, M.; Bremhorst, A.; Amir, S.; Distelfeld, T.; Dassa, Y.; Yaroshetsky, S.; Riemer, S.; Shimshoni, I.; Mills, D.S.; et al. Explainable Automated Recognition of Emotional States from Canine Facial Expressions: The Case of Positive Anticipation and Frustration. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 22611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, D.S. Perspectives on Assessing the Emotional Behavior of Animals with Behavior Problems. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2017, 16, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, M.C.; Monteiro, B.P.; Steagall, P.V. Measurement Properties of Grimace Scales for Pain Assessment in Nonhuman Mammals: A Systematic Review. Pain 2022, 163, e697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogil, J.S.; Pang, D.S.J.; Silva Dutra, G.G.; Chambers, C.T. The Development and Use of Facial Grimace Scales for Pain Measurement in Animals. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 116, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, D.J.; Bailey, A.L.; Chanda, M.L.; Clarke, S.E.; Drummond, T.E.; Echols, S.; Glick, S.; Ingrao, J.; Klassen-Ross, T.; LaCroix-Fralish, M.L.; et al. Coding of Facial Expressions of Pain in the Laboratory Mouse. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 447–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalla Costa, E.; Minero, M.; Lebelt, D.; Stucke, D.; Canali, E.; Leach, M.C. Development of the Horse Grimace Scale (HGS) as a Pain Assessment Tool in Horses Undergoing Routine Castration. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häger, C.; Biernot, S.; Buettner, M.; Glage, S.; Keubler, L.M.; Held, N.; Bleich, E.M.; Otto, K.; Müller, C.W.; Decker, S.; et al. The Sheep Grimace Scale as an Indicator of Post-Operative Distress and Pain in Laboratory Sheep. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotocina, S.G.; Sorge, R.E.; Zaloum, A.; Tuttle, A.H.; Martin, L.J.; Wieskopf, J.S.; Mapplebeck, J.C.; Wei, P.; Zhan, S.; Zhang, S.; et al. The Rat Grimace Scale: A Partially Automated Method for Quantifying Pain in the Laboratory Rat via Facial Expressions. Mol. Pain 2011, 7, 1744–8069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banchi, P.; Quaranta, G.; Ricci, A.; Degerfeld, M.M. von Reliability and Construct Validity of a Composite Pain Scale for Rabbit (CANCRS) in a Clinical Environment. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0221377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscardi, A.V.; Hunniford, M.; Lawlis, P.; Leach, M.; Turner, P.V. Development of a Piglet Grimace Scale to Evaluate Piglet Pain Using Facial Expressions Following Castration and Tail Docking: A Pilot Study. Front. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slice, D.E. Geometric Morphometrics. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2007, 36, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finka, L.R.; Luna, S.P.; Brondani, J.T.; Tzimiropoulos, Y.; McDonagh, J.; Farnworth, M.J.; Ruta, M.; Mills, D.S. Geometric Morphometrics for the Study of Facial Expressions in Non-Human Animals, Using the Domestic Cat as an Exemplar. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laakasuo, M.; Herzon, V.; Perander, S.; Drosinou, M.; Sundvall, J.; Palomäki, J.; Visala, A. Socio-Cognitive Biases in Folk AI Ethics and Risk Discourse. AI Ethics 2021, 1, 593–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feighelstein, M.; Shimshoni, I.; Finka, L.R.; Luna, S.P.L.; Mills, D.S.; Zamansky, A. Automated Recognition of Pain in Cats. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giersberg, M.F.; Meijboom, F.L.B. Caught on Camera: On the Need of Responsible Use of Video Observation for Animal Behavior and Welfare Research. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 864677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, D.; Hand, E. Bridging the Gap Between Automated and Human Facial Emotion Perception. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 2401–2411. [Google Scholar]

- McDuff, D.; Mahmoud, A.; Mavadati, M.; Amr, M.; Turcot, J.; el Kaliouby, R. AFFDEX SDK: A Cross-Platform Real-Time Multi-Face Expression Recognition Toolkit. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 May 2016; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 3723–3726. [Google Scholar]

- Girard, J.M.; Cohn, J.F.; Jeni, L.A.; Sayette, M.A.; De la Torre, F. Spontaneous Facial Expression in Unscripted Social Interactions Can Be Measured Automatically. Behav. Res. 2015, 47, 1136–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, J.; Kohler, C.G.; Gur, R.C.; Verma, R. Automated Facial Action Coding System for Dynamic Analysis of Facial Expressions in Neuropsychiatric Disorders. J. Neurosci. Methods 2011, 200, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, R.S. Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 175–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, M.L.; Holman, L.; Lanfear, R.; Kahn, A.T.; Jennions, M.D. The Extent and Consequences of P-Hacking in Science. PLoS Biol. 2015, 13, e1002106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amrhein, V.; Trafimow, D.; Greenland, S. Inferential Statistics as Descriptive Statistics: There Is No Replication Crisis If We Don’t Expect Replication. Am. Stat. 2019, 73, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicherts, J.M.; Veldkamp, C.L.S.; Augusteijn, H.E.M.; Bakker, M.; van Aert, R.C.M.; van Assen, M.A.L.M. Degrees of Freedom in Planning, Running, Analyzing, and Reporting Psychological Studies: A Checklist to Avoid p-Hacking. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, J.; Bray, E.; Buchsbaum, D.; Byosiere, S.-E.; Byrne, M.; Freeman, M.S.; Gnanadesikan, G.; Guran, C.-N.A.; Horschler, D.; Huber, L.; et al. ManyDogs 1: A Multi-Lab Replication Study of Dogs’ Pointing Comprehension. Preprint 2021. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Correia-Caeiro, C.; Zamansky, A.; Karl, S.; Bremhorst, A. Research Methods for the Analysis of Visual Emotion Cues in Animals: A Workshop Report. Animals 2025, 15, 3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213142

Correia-Caeiro C, Zamansky A, Karl S, Bremhorst A. Research Methods for the Analysis of Visual Emotion Cues in Animals: A Workshop Report. Animals. 2025; 15(21):3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213142

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorreia-Caeiro, Catia, Anna Zamansky, Sabrina Karl, and Annika Bremhorst. 2025. "Research Methods for the Analysis of Visual Emotion Cues in Animals: A Workshop Report" Animals 15, no. 21: 3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213142

APA StyleCorreia-Caeiro, C., Zamansky, A., Karl, S., & Bremhorst, A. (2025). Research Methods for the Analysis of Visual Emotion Cues in Animals: A Workshop Report. Animals, 15(21), 3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213142