Effects of Yeast Culture Supplementation on Milk Yield and Milk Composition in Holstein Dairy Cows: A Meta-Analysis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Literature Screening and Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Selection Process

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Quality Assessment

3.4. Effects of YC on Milk Yield

3.5. Effects of YC on Milk Fat Percentage

3.6. Effect of YC on Milk Protein Percentage

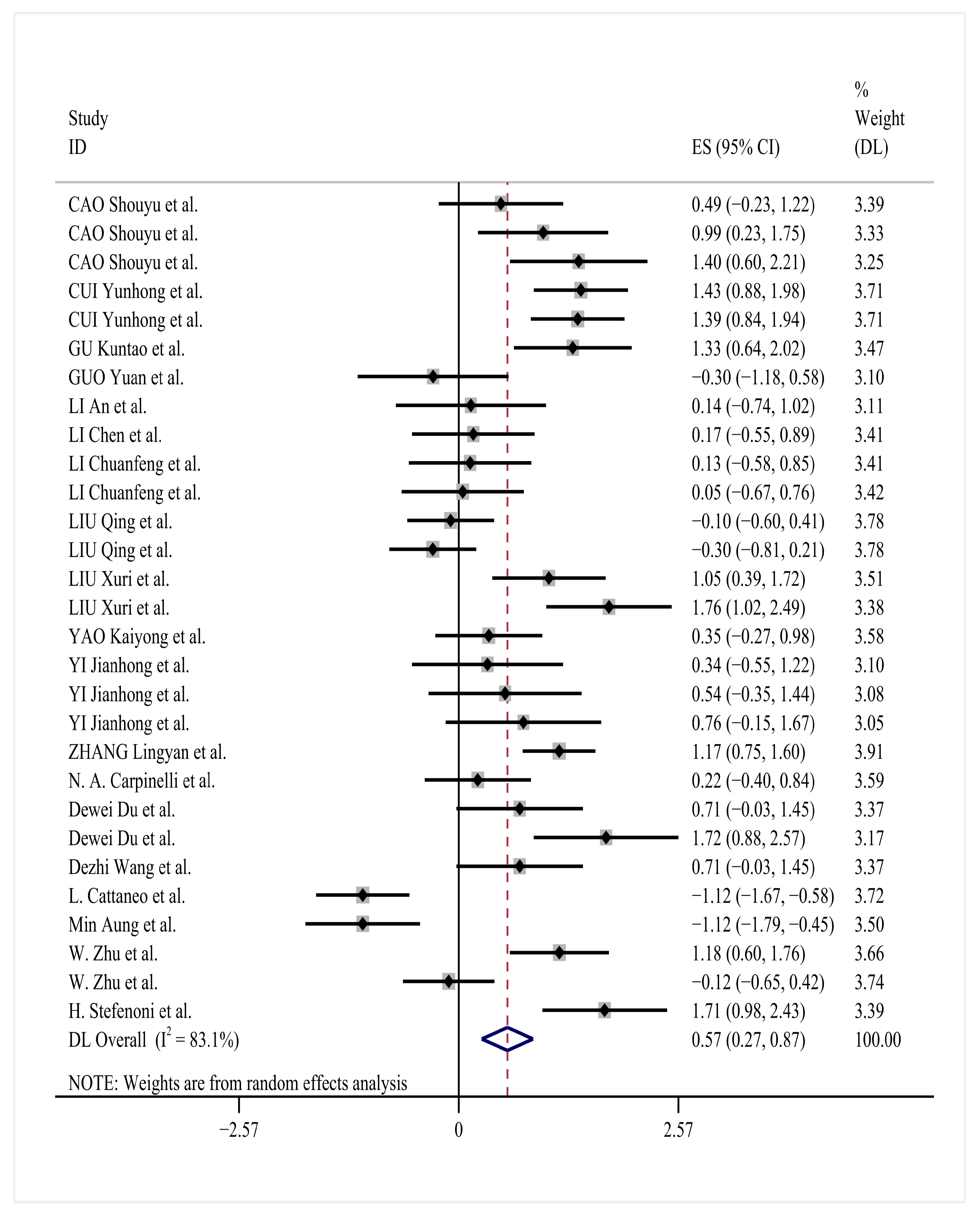

3.7. Effect of YC on Milk Lactose Percentage

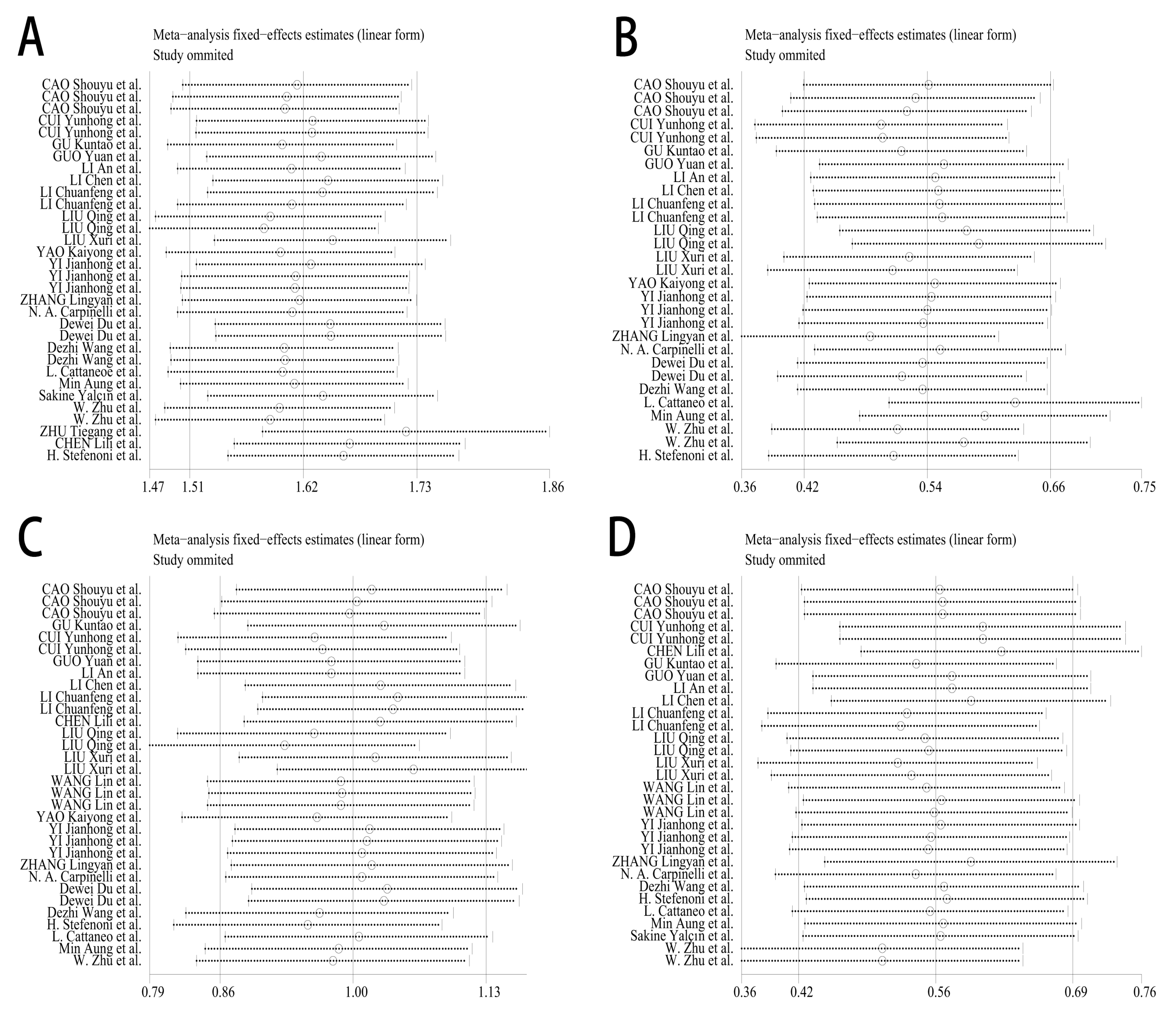

3.8. Sensitivity Analysis

3.9. Publication Bias Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nguyen, B.T.; Briggs, K.R.; Eicker, S.; Overton, M.; Nydam, D.V. Herd turnover rate reexamined, a tool for improving profitability, welfare, and sustainability. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2022, 84, ajvr.22.10.0177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.L.G.; Freitas, J.A.; Micai, B.; Azevedo, R.A.; Greco, L.F.; Santos, J.E.P. Effect of supplemental yeast culture and dietary starch content on rumen fermentation and digestion in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perricone, V.; Sandrini, S.; Irshad, N.; Savoini, G.; Comi, M.; Agazzi, A. Yeast-derived products, the role of hydrolyzed yeast and yeast culture in poultry nutrition—A review. Animals 2022, 12, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, H.A.; Martin, S.A. Effects of Saccharomyces cerevisiae culture and Saccharomyces cerevisiae live cells on in vitro mixed ruminal microorganism fermentation. J. Dairy Sci. 2002, 85, 2603–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desnoyers, M.; Giger-Reverdin, S.; Bertin, G.; Duvaux-Ponter, C.; Sauvant, D. Meta-analysis of the influence of Saccharomyces cerevisiae supplementation on ruminal parameters and milk production of ruminants. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 1620–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nueraihemaiti, G.; Huo, X.; Zhang, H.; Shi, H.; Gao, Y.; Zeng, J.; Lin, Q.; Lou, K. Effect of diet supplementation with two yeast cultures on rumen fermentation parameters and microbiota of fattening sheep in vitro. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, A.; Iglesias, C.; Devant, M. Daily rumen pH pattern of loose-housed dairy cattle as affected by feeding pattern and live yeast supplementation. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2007, 136, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchemin, K.A.; Krehbiel, C.R.; Newbold, C.J. Enzymes, bacterial direct-fed microbials, and yeast, principles for use in ruminant nutrition. In Biology of Growing Animals; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 4, pp. 251–284. [Google Scholar]

- Erasmus, L.J.; Botha, P.; Kistner, A. Effect of yeast culture supplement on production, rumen fermentation, and duodenal nitrogen flow in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1992, 75, 3056–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meller, R.A.; Wenner, B.A.; Ashworth, J.; Gehman, A.M.; Lakritz, J.; Firkins, J.L. Potential roles of nitrate and live yeast culture in suppressing methane emission and influencing ruminal fermentation, digestibility, and milk production in lactating Jersey cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 6144–6156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Feng, L.; Chen, P.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhai, R.; Hu, Z. Effects of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cultures on performance and immune performance of dairy cows during heat stress. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 851184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, C.; Baumgartner, J.; Malan, L.; Smuts, C.M. Determining sample size adequacy for animal model studies in nutrition research, limits and ethical challenges of ordinary power calculation procedures. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 71, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleiss, J.L. The statistical basis of meta-analysis. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 1993, 2, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poppy, G.D.; Rabiee, A.R.; Lean, I.J.; Sanchez, W.K.; Dorton, K.L.; Morley, P.S. A meta-analysis of the effects of feeding yeast culture produced by anaerobic fermentation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae on milk production of lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 6027–6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawneh, J.I.; Barreto, M.O.; Moore, R.J.; Soust, M.; Al-Harbi, H.; James, A.S.; Krishnan, D.; Olchowy, T.W.J. Systematic review of an intervention, the use of probiotics to improve health and productivity of calves. Prev. Vet. Med. 2020, 183, 105147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorini, M.L.; Soto, L.P.; Zbrun, M.V.; Sequeira, G.J.; Rosmini, M.R.; Frizzo, L.S. Impact of probiotic administration on the health and fecal microbiota of young calves, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of lactic acid bacteria. Res. Vet. Sci. 2012, 93, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocks, K.; Torgerson, D.J. Sample size calculations for pilot randomized trials, a confidence interval approach. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013, 66, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, M.D.; Chang, S.S. Enhanced recovery pathways versus standard care after cystectomy, a meta-analysis of the effect on perioperative outcomes. Eur. Urol. 2016, 70, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Pierre, N.R. Invited review, integrating quantitative findings from multiple studies using mixed model methodology. J. Dairy Sci. 2001, 84, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.Y. Effects of Yeast Culture Supplementation in Diets under High Temperature Conditions on Production Performance and Antioxidant Capacity of Dairy Cows. Chin. Dairy Ind. 2024, 1, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, K.Y.; Wang, D.M. Effects of Yeast Culture Supplementation under Heat Stress on Production Performance and Ketosis Risk in Dairy Cows. China Dairy Cattle 2023, 07, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, K.; Zhao, L.; Wang, L.; Bu, D.; Liu, N.; Wang, J. Effects of Dietary Yeast β-Glucan Supplementation on Production Performance, Serum Biochemical Parameters, and Antioxidant Capacity in Periparturient Dairy Cows. Acta Zoonutr. Sin. 2018, 30, 2164–2171. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.Y. Effects of Yeast Culture on Lactation Performance of Holstein Dairy Cows. Feed Livest. 2017, 19, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, J.H. Effects of Yeast Culture Supplementation on Production Performance and Blood Biochemical Parameters in Dairy Cows. Livest. Poult. Ind. 2024, 35, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.F.; Zeng, S.F. Effects of Yeast Culture Supplementation under High Temperature Conditions on Production Performance and Blood Biochemical Parameters in Dairy Cows. China Feed 2024, 16, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, G.L.; Narintuya. Effects of Yeast Culture Supplementation on Milk Production and Serum Inflammatory Parameters in Dairy Cows. China Feed 2023, 18, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Lu, N.; Li, F.; Li, S.; Shao, W. Effects of Yeast Culture on Lactation Performance, Apparent Digestibility, and Serum Biochemical Parameters in Early Lactation Dairy Cows. Feed Res. 2021, 44, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, T.; Pang, Q.; Wang, S.; Sun, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, L. Effects of Yeast Culture Supplementation on Dry Matter Intake, Milk Yield, and Serum Parameters in Dairy Cows. Feed Res. 2021, 44, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.H.; Tubu. Effects of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Fermentation Product on Milk Production and Lipopolysaccharide Concentration in Dairy Cows. China Feed 2020, 18, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.R.; Hao, Z.H.; Zhang, H.J. Effects of Yeast Culture Supplementation on Lactation Performance and Apparent Nutrient Digestibility in Heat-Stressed Dairy Cows. China Feed 2019, 08, 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Lv, Y.; Chen, Z.; Du, G.; Li, J.; Fu, S.; Sun, G. Effects of Composite Yeast Culture on Milk Production, Nitrogen Excretion, and Blood Biochemical Parameters in Dairy Cows. Acta Pratacult. Sin. 2015, 24, 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Li, A.; Guo, X.Q.; Li, Y.L. Effects of Composite Yeast Culture on Production Performance in Dairy Cows. China Dairy Cattle 2012, 10, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y. Effects of Feeding Composite Yeast Culture on Milk Yield and Milk Composition in Dairy Cows. Sci. Innov. Appl. 2016, 30, 54–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Yao, D.; Yang, C.; Lu, N.; Ma, Y. Effects of Dietary Composite Yeast Culture Supplementation on Milk Production in Dairy Cows. Feed Res. 2019, 42, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, B.X.; Yao, K.Y.; Yoon, I.; Chung, Y.H.; Wang, J.K.; Liu, J.X. Effects of Supplemental Levels of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Fermentation Product on Lactation Performance in Dairy Cows under Heat Stress. Asian-Australas J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 29, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Wang, X.; Cheng, H.; Yin, W.; An, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhen, Y. Effect of Yeast Culture Supplementation on Rumen Microbiota, Regulation Pathways, and Milk Production in Dairy Cows of Different Parities. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2025, 321, 116244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçın, S.; Yalçın, S.; Can, P.; Gürdal, A.O.; Bağcı, C.; Eltan, Ö. The Nutritive Value of Live Yeast Culture (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and Its Effect on Milk Yield, Milk Composition and Some Blood Parameters of Dairy Cows. Asian-Australas J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 24, 1377–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, M.; Ohtsuka, H.; Izumi, K. Effect of Yeast Cell Wall Supplementation on Production Performances and Blood Biochemical Indices of Dairy Cows in Different Lactation Periods. Vet. World 2019, 12, 796–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, L.; Lopreiato, V.; Piccioli-Cappelli, F.; Trevisi, E.; Minuti, A. Effect of supplementing live Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast on performance, rumen function, and metabolism during the transition period in Holstein dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 4353–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefenoni, H.; Harrison, J.H.; Adams-Progar, A.; Block, E. Effect of Enzymatically Hydrolyzed Yeast on Health and Performance of Transition Dairy Cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 1541–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpinelli, N.A.; Halfen, J.; Trevisi, E.; Chapman, J.D.; Sharman, E.D.; Anderson, J.L.; Osorio, J.S. Effects of Peripartal Yeast Culture Supplementation on Lactation Performance, Blood Biomarkers, Rumen Fermentation, and Rumen Bacteria Species in Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 10727–10743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Z.; Zhou, G.; Yao, J. Effects of supplementation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae products on dairy calves, a meta-analysis. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 7386–7398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Yang, Q.; Sha, Y.; Jiao, T.; Zhao, S. Effects of yeast cultures on meat quality, flavor composition, and rumen microbiota in lambs. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 9, 100845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basarab, J.A.; Beauchemin, K.A.; Baron, V.S.; Oba, O.; Guan, L.L. Reducing GHG emissions through genetic improvement for feed efficiency, effects on economically important traits and enteric methane production. Animal 2013, 7 (Suppl. 2), 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.F. Saccharomyces cerevisiae β-glucan-induced SBD-1 expression in ovine ruminal epithelial cells is mediated through the TLR-2-MyD88-NF-κB/MAPK pathway. Vet. Res. Commun. 2019, 43, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.E.; Zhang, A.; Han, R.; Xu, C.; Zhang, N.; Jiang, X.; Wang, S. Changes of fecal microbiota with supplementation of Acremonium terricola culture and yeast culture in ewes during lactation. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 103, skaf174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Year | Parity | Days in Milk (days) | Country | Sample Size | Trial Duration (days) | Yeast Culture Type | Treatment Groups | Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAO Shouyu et al. | 2024 | - | - | China | 20 | 21 | yeast culture | 10 g/d, 15 g/d, 20 g/d | ①②③④ |

| YAO Kaiyong et al. | 2023 | 2.63 ± 0.21 | 165 ± 14.2 | China | 40 | 56 | yeast culture | 15 g/d | ①②③④ |

| GU Kuntao et al. | 2018 | 2.88 ± 0.05 | 1–21 Postpartum | China | 49 | 42 | yeast β-glucan | 10 g/d | ①②③④ |

| ZHANG Lingyan et al. | 2017 | 2.04 ± 0.20 | 136.10 ± 15.80 | China | 100 | 30 | yeast culture | 20 g/d | ①②③ |

| YI Jianhong et al. | 2024 | - | - | China | 40 | 45 | yeast culture | 50 g/d, 100 g/d, 200 g/d | ①②③ |

| LI Chuanfeng et al. | 2024 | - | - | China | 45 | 56 | yeast culture | 100 g/d, 200 g/d | ①②③④ |

| LIU Qing et al. | 2023 | 2~3 | - | China | 90 | 30 | yeast culture | 25 g/d, 50 g/d | ①②③ |

| LI Chen et al. | 2021 | 3.20 ± 0.84 | 20 ± 3 | China | 30 | 90 | yeast culture | 30 g/d | ①②③④ |

| ZHU Tiegang et al. | 2021 | 2.62 | 116.01 | China | 600 | 31 | Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Cultures | 120 g/d | ① |

| CUI Yunhong et al. | 2020 | - | 28–135 | China | 64 | 28 | Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Cultures | 60 g/d | ①②③ |

| LIU Xuri et al. | 2019 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 35 ± 5 | China | 60 | 56 | yeast culture | 100 g/d, 200 g/d | ①②③④ |

| WANG Lin et al. | 2015 | 2.55 ± 1.24 | 135 ± 15 | China | 24 | 56 | compound yeast cultures | 80 g/d, 100 g/d, 120 g/d | ①②③④ |

| LI An et al. | 2023 | 2.50 ± 0.45 | 120.10 ± 31.45 | China | 20 | 30 | compound yeast cultures | 12.5 kg/TMR | ①②③④ |

| GUO Yuan et al. | 2016 | - | - | China | 20 | 30 | compound yeast cultures | 400 g/d | ①②③④ |

| CHEN Lili et al. | 2019 | - | 100–160 | China | 38 | 30 | compound yeast cultures | 200 g/d | ①②③④ |

| W. Zhu et al. | 2015 | 2.88 ± 0.91 | 204 ± 46 | China | 81 | 56 | Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Cultures | 120 g/d, 240 g/d | ① |

| Dezhi Wang et al. | 2025 | 2.6 ± 0.14 | 0–21, 22–60 | China | 60 | 60 | yeast culture | 150 g/d | ①②③④ |

| Dewei Du et al. | 2022 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 158 ± 14 | China | 45 | 60 | Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Cultures | 30 g/d, 100 g/d | ①②④ |

| Min Aung et al. | 2019 | - | 81 ± 7 | Japan | 32 | 56 | yeast cell wall | 10 g/d | ①②③④ |

| Sakine Yalçın et al. | 2011 | - | 90 ± 35 | Turkey | 6 | 50 | Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Cultures | 50 g/d | ①②③④ |

| L. Cattaneo et al. | 2022 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | - | Italy | 10 | 70 | Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Cultures | 10 g/d | ①②③④ |

| H. Stefenoni et al. | 2019 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | −21–60 | America | 40 | 81 | enzymatically hydrolyzed yeast | 28 g/d, 56 g/d | ①②③④ |

| N. A. Carpinelli et al. | 2020 | 2.62 ± 0.3 | −30 ± 6 to 50 | America | 40 | 80 | yeast culture | 114 g/d | ①②③④ |

| Category | Subgroup | Studies (n) | I2 (%) | Effect Model | SMD (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture Type | General Yeast Cultures | 16 | 88.2 | Random | 2.03 (1.83, 2.22) | <0.0001 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae-Based | 8 | 86.9 | Random | 1.49 (1.35, 1.64) | <0.0001 | |

| Specialized Yeast Components | 2 | 93 | Random | 1.45 (0.96, 1.94) | <0.0001 | |

| Composite Yeast Cultures | 2 | 89.4 | Random | 0.67 (0.09, 1.16) | 0.007 | |

| Dosage (g/day) | 10–50 | 14 | 89.9 | Random | 1.87 (1.67, 2.08) | <0.0001 |

| 60–120 | 7 | 72.4 | Random | 1.47 (1.33, 1.62) | <0.0001 | |

| >120 | 8 | 92.5 | Random | 1.69 (1.43, 1.96) | <0.0001 | |

| Feeding Duration (days) | 21–30 | 11 | 90 | Random | 1.60 (1.46, 1.74) | <0.0001 |

| 42–56 | 14 | 86.3 | Random | 1.73 (1.52, 1.93) | <0.0001 | |

| 60–90 | 4 | 84 | Random | 1.45 (1.07, 1.83) | <0.0001 |

| Category | Subgroup | Studies (n) | I2 | Effect Model | SMD (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture Type | General Yeast Cultures | 16 | 67.90% | Random | 0.53 (0.37, 0.69) | <0.0001 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae-Based | 6 | 91.70% | Random | 0.63 (0.40, 0.85) | <0.0001 | |

| Specialized Yeast Components | 2 | 94.80% | Random | 0.57 (0.16, 0.97) | 0.006 | |

| Composite Yeast Cultures | 1 | 0 | Random | −0.08 (−0.70, 0.54) | 0.806 | |

| Dosage (g/day) | 10–50 | 14 | 87.40% | Random | 0.37 (0.21, 0.54) | <0.0001 |

| 60–120 | 6 | 54.00% | Random | 1.02 (0.78, 1.27) | <0.0001 | |

| >120 | 6 | 71.80% | Random | 0.4 (0.12, 0.67) | 0.005 | |

| Feeding Duration (days) | 21–30 | 9 | 82.80% | Random | 0.68 (0.49, 0.87) | <0.0001 |

| 42–56 | 10 | 84.90% | Random | 0.43 (0.22, 0.63) | <0.0001 | |

| 60–90 | 7 | 83.90% | Random | 0.46 (0.21, 0.71) | <0.0001 |

| Category | Subgroup | Studies (n) | I2 (%) | Effect | SMD (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | ||||||

| Culture Type | General Yeast Cultures | 15 | 87.1 | Random | 0.88 (0.70, 1.05) | <0.0001 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae-Based | 6 | 78.1 | Random | 0.96 (0.70, 1.21) | <0.0001 | |

| Specialized Yeast Components | 2 | 94.3 | Random | 1.43 (0.92, 1.94) | <0.0001 | |

| Composite Yeast Cultures | 5 | 89.2 | Random | 1.73 (1.23, 2.23) | <0.0001 | |

| Dosage (g/day) | 10–50 | 13 | 87.3 | Random | 1.15 (0.94,1.36) | <0.0001 |

| 60–120 | 8 | 88.3 | Random | 0.82 (0.56, 1.08) | <0.0001 | |

| >120 | 8 | 87.4 | Random | 0.95 (0.71, 1.18) | <0.0001 | |

| Feeding Duration (days) | 21–30 | 8 | 82.8 | Random | 1.21 (0.90, 1.34) | <0.0001 |

| 42–56 | 15 | 84.9 | Random | 0.95 (0.75, 1.15) | <0.0001 | |

| 60–90 | 6 | 83.9 | Random | 0.86 (0.55, 1.17) | <0.0001 |

| Category | Subgroup | Studies (n) | I2 (%) | Effect Model | SMD (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture Type | General Yeast Cultures | 14 | 53.3 | Random | 0.79 (0.59, 1.00) | <0.0001 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae-Based | 6 | 84.6 | Random | 0.50 (0.25, 0.74) | <0.0001 | |

| Specialized Yeast Components | 2 | 29 | Random | 0.56 (0.14, 0.98) | <0.0001 | |

| Composite Yeast Cultures | 5 | 60.1 | Random | −0.13 (−0.51, 0.25) | <0.0001 | |

| Dosage (g/day) | 10–50 | 13 | 27 | Random | 0.43 (0.22, 0.65) | <0.0001 |

| 60–120 | 8 | 74.1 | Random | 0.63 (0.39, 0.87) | <0.0001 | |

| >120 | 7 | 86.4 | Random | 0.66 (0.39, 0.93) | <0.0001 | |

| Feeding Duration (days) | 21–30 | 10 | 44 | Random | 0.06 (−0.15, 0.27) | <0.0001 |

| 42–56 | 14 | 40.5 | Random | 1.15 (0.94, 1.37) | <0.0001 | |

| 60–90 | 4 | 55.10% | Random | 0.39 (0.06, 0.72) | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiang, H.; Dong, X.; Lin, X.; Hou, Q.; Wang, Z. Effects of Yeast Culture Supplementation on Milk Yield and Milk Composition in Holstein Dairy Cows: A Meta-Analysis. Animals 2025, 15, 3065. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213065

Xiang H, Dong X, Lin X, Hou Q, Wang Z. Effects of Yeast Culture Supplementation on Milk Yield and Milk Composition in Holstein Dairy Cows: A Meta-Analysis. Animals. 2025; 15(21):3065. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213065

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiang, Hongyan, Xusheng Dong, Xueyan Lin, Qiuling Hou, and Zhonghua Wang. 2025. "Effects of Yeast Culture Supplementation on Milk Yield and Milk Composition in Holstein Dairy Cows: A Meta-Analysis" Animals 15, no. 21: 3065. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213065

APA StyleXiang, H., Dong, X., Lin, X., Hou, Q., & Wang, Z. (2025). Effects of Yeast Culture Supplementation on Milk Yield and Milk Composition in Holstein Dairy Cows: A Meta-Analysis. Animals, 15(21), 3065. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213065