Transcriptomic Analysis of MGF360–4L Mediated Regulation in African Swine Fever Virus-Infected Porcine Alveolar Macrophages

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells and Viruses

2.2. Preparation of Transcriptome Samples

2.3. Extraction and Quantification of Total RNA

2.4. Construction of cDNA Library

- Purification and fragmentation of mRNA.

- Synthesis of the first strand of cDNA.

- Synthesis of the second strand of cDNA and purification of the second strand products.

- Perform end repair and 3′-end A-tailing on the above products, followed immediately by adapter ligation reaction.

- Purification of ligation products and fragment selection.

- PCR amplification and purification; Qsep−400 was used for quality inspection.

2.5. RNA Sequencing

2.6. Sequence Alignment

2.7. Gene Expression Level Analysis

2.8. Differential Gene Expression Analysis

2.9. Bioinformatics Analysis

3. Results

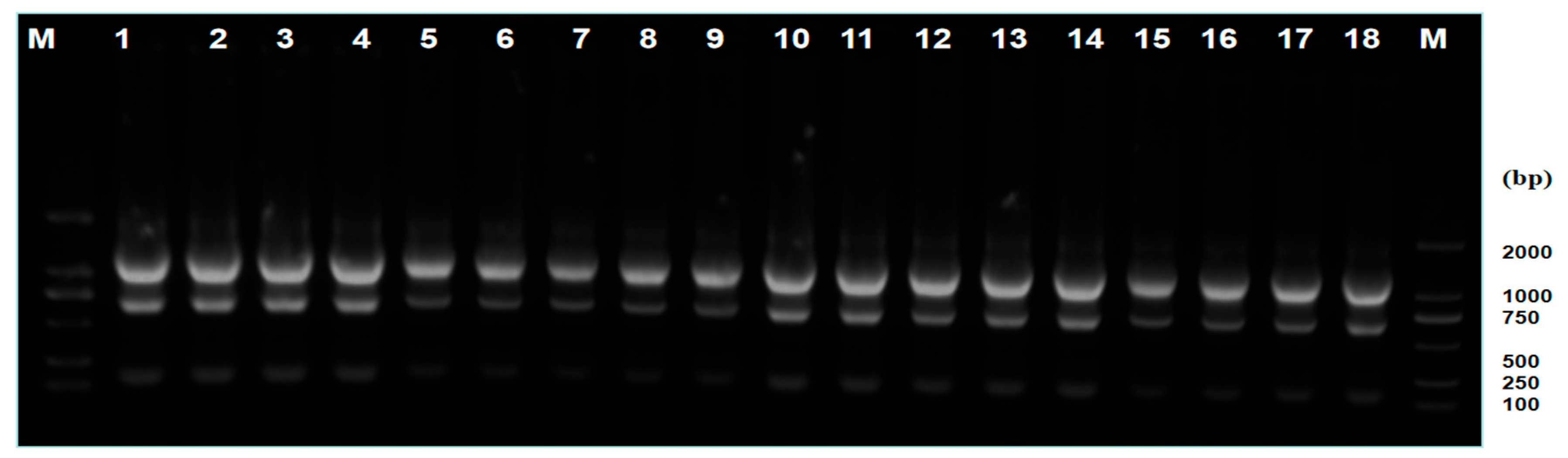

3.1. RNA Quality Detection

3.2. RNA-seq Data Quality Metrics

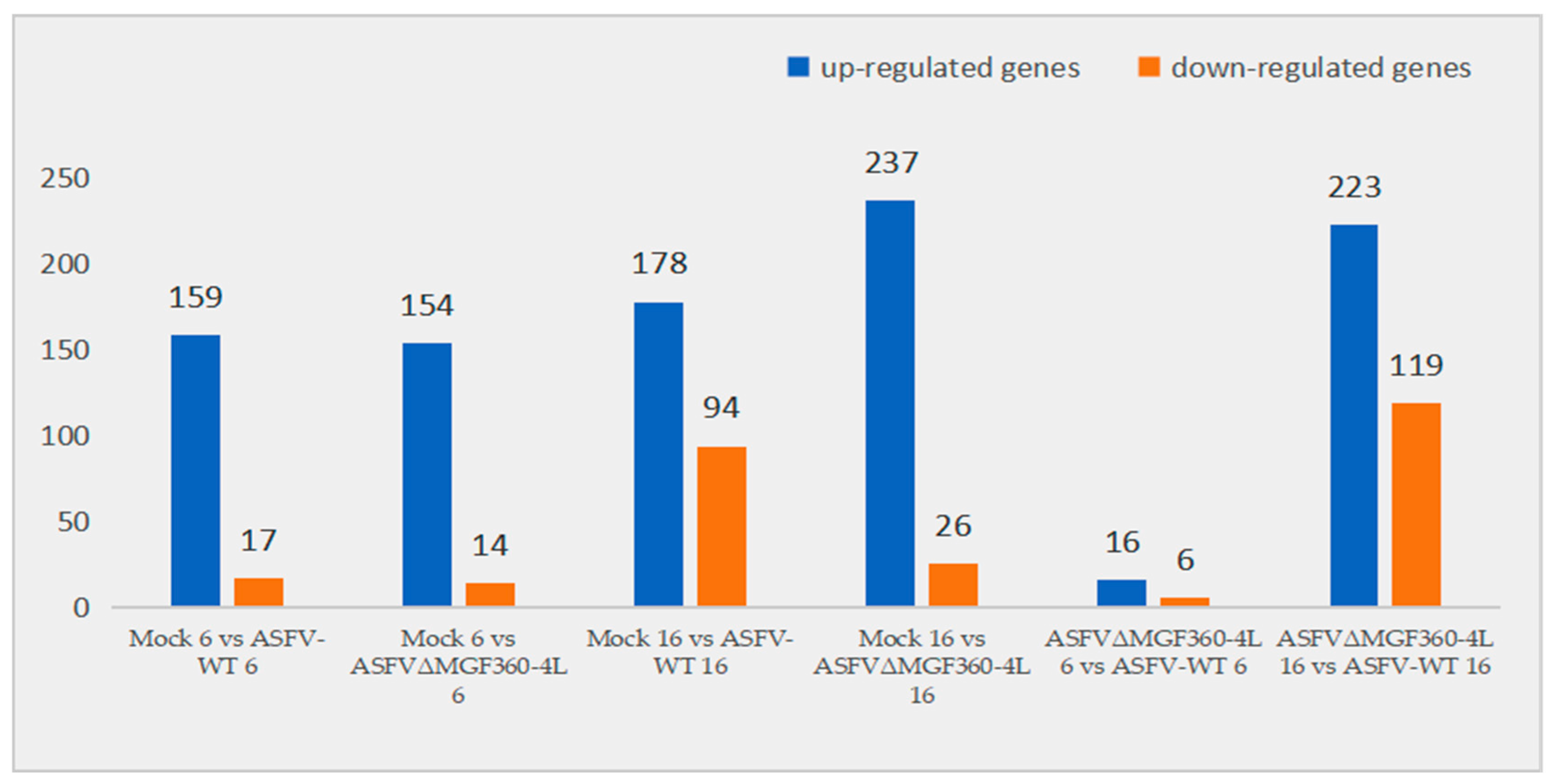

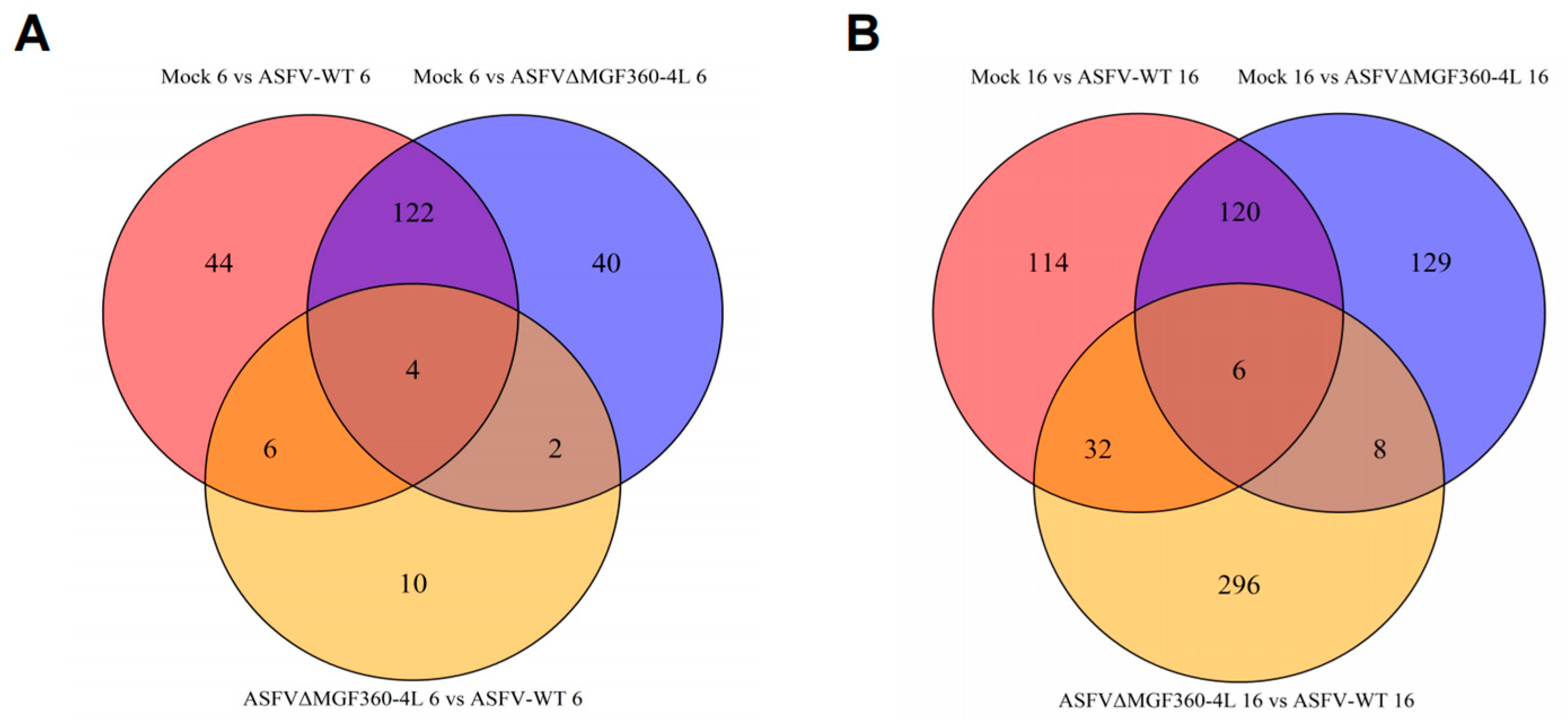

3.3. Differential Expression Analysis of PAMs Infected with ASFV-WT and ASFVΔMGF360–4L

3.4. GO Enrichment Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

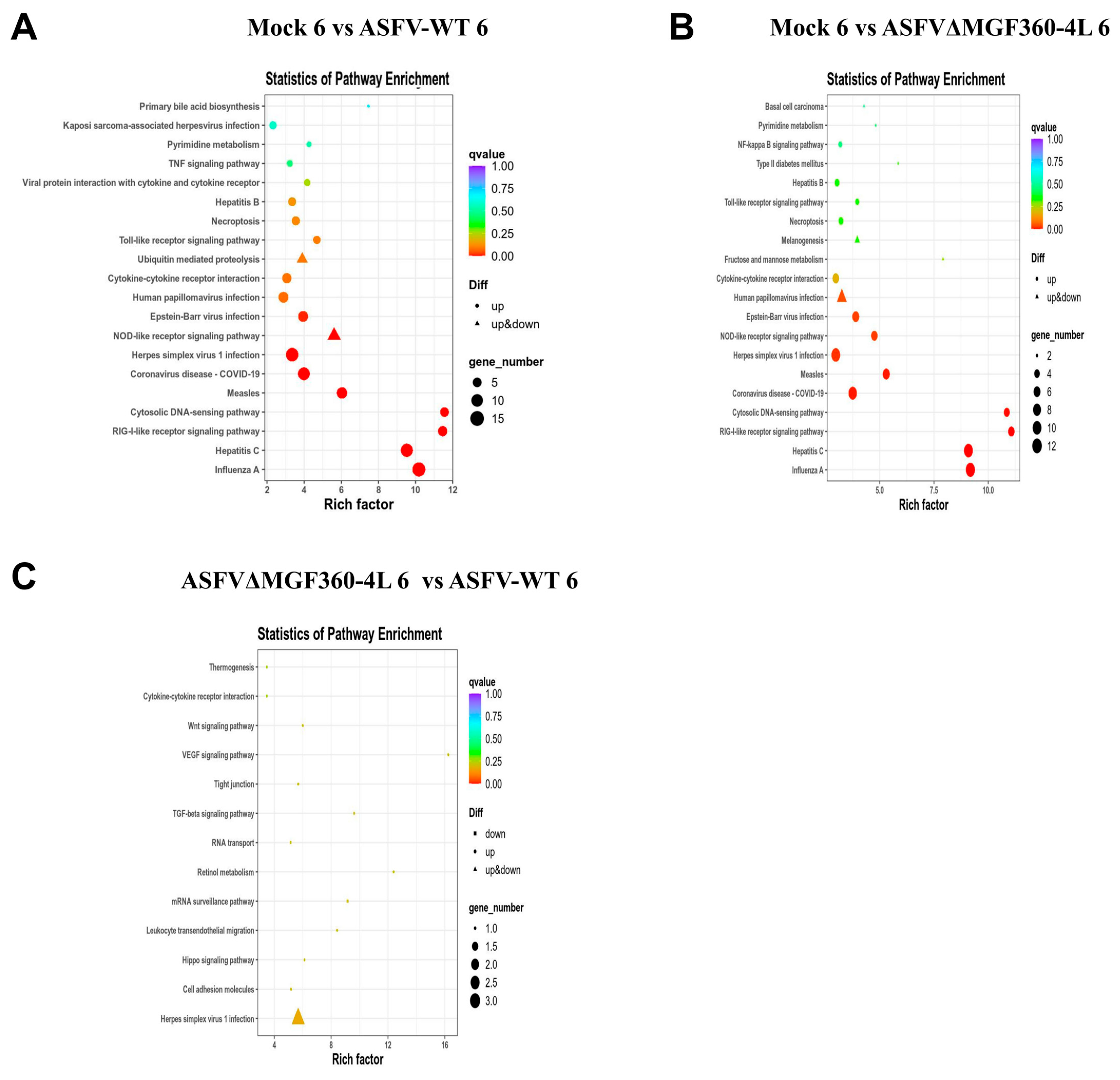

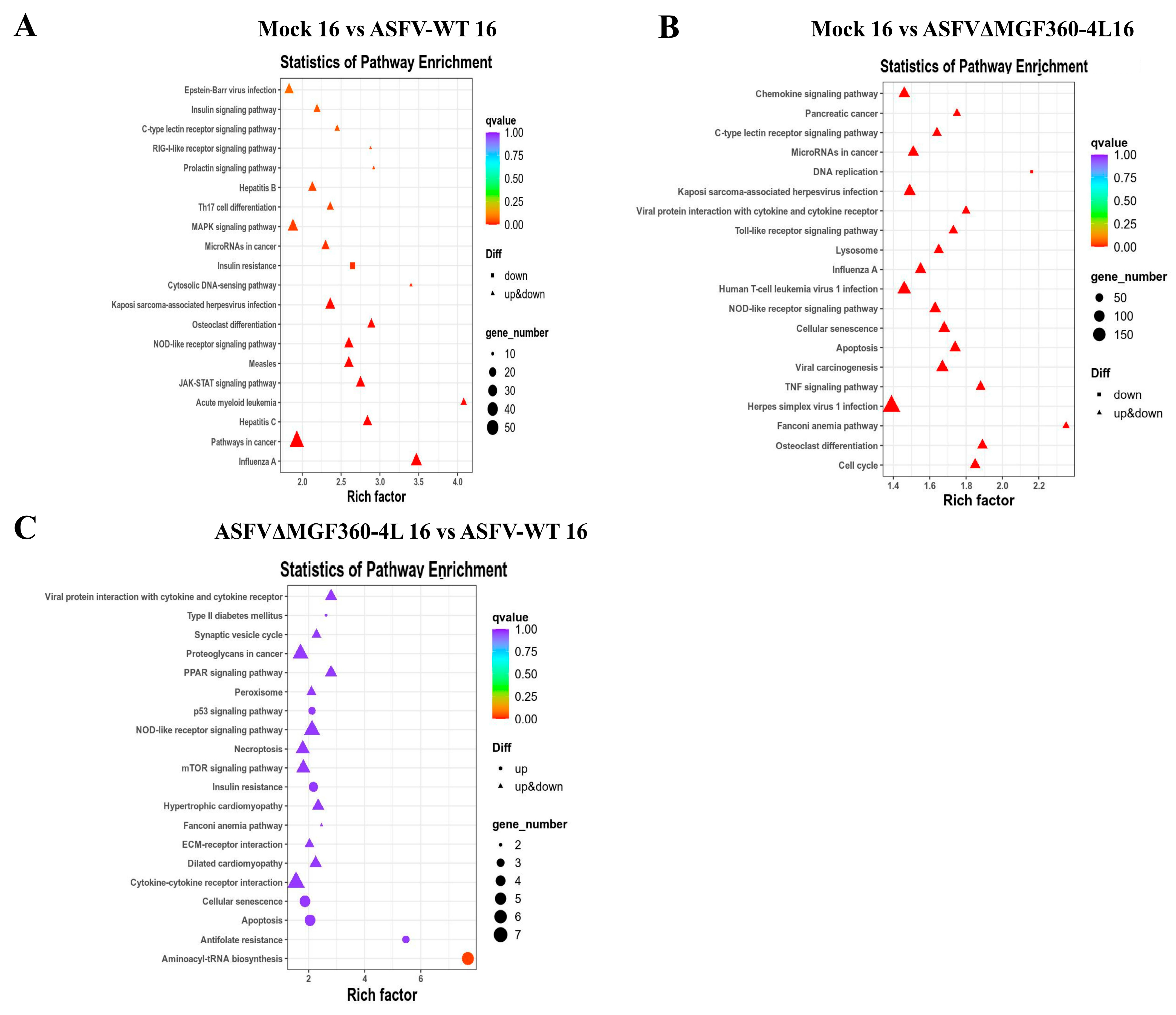

3.5. KEGG Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

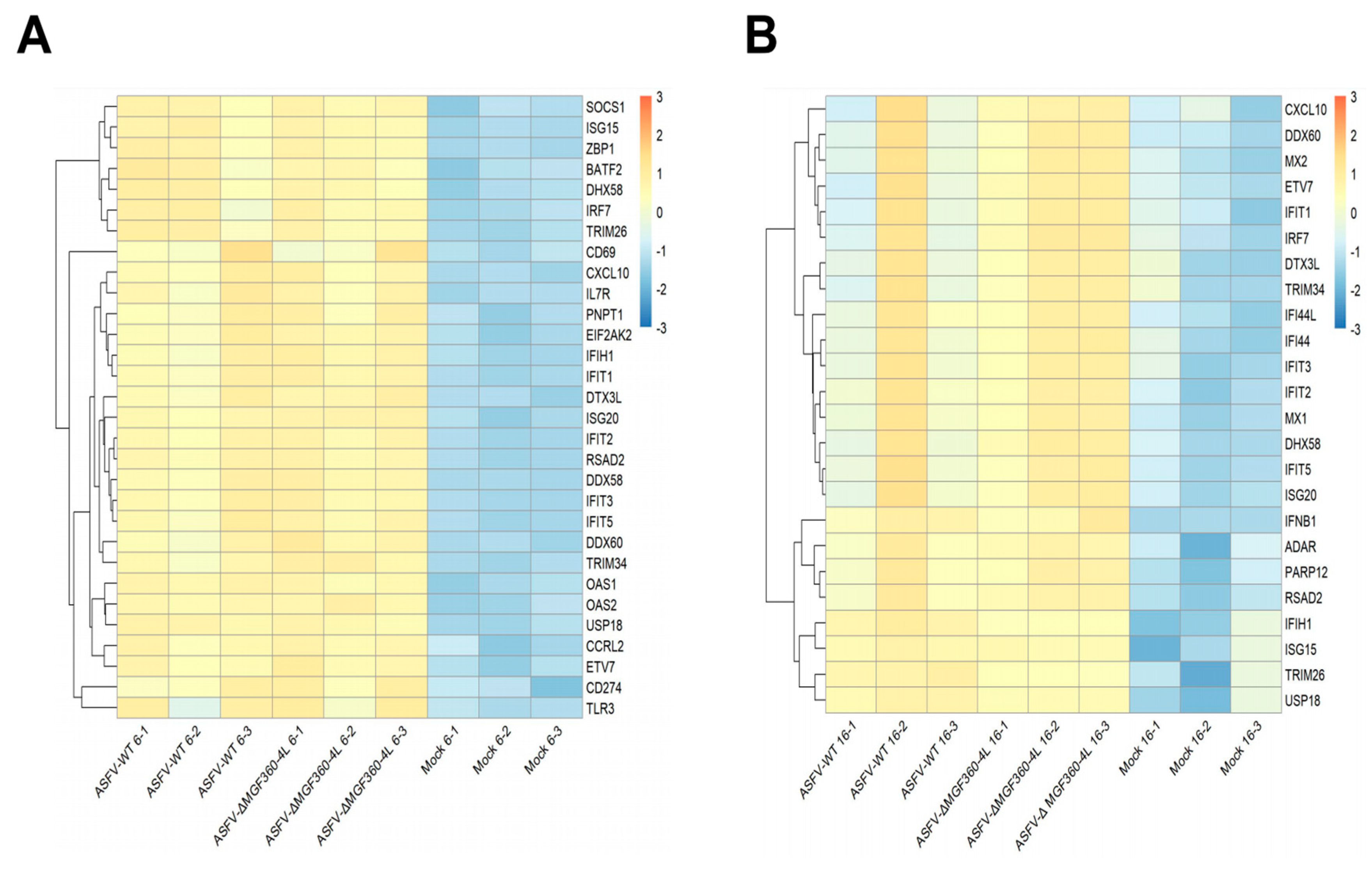

3.6. Differential Expression of Host Innate Immune Genes in ASFV-Infected PAM Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASF | African swine fever |

| ASFV | African swine fever virus |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| ORF | Open Reading Frame |

| RHIM | Receptor-interacting protein kinase homotypic interaction motif |

| SPF | Specific-pathogen-free |

| PAM | Porcine alveolar macrophages |

| DEG | Differential expression analysis |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

| CSFV | Classical swine fever virus |

References

- Arias, M.; Jurado, C.; Gallardo, C.; Fernández-Pinero, J.; Sánchez-Vizcaíno, J.M. Gaps in African swine fever: Analysis and priorities. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65 (Suppl. S1), 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cordon, P.J.; Montoya, M.; Reis, A.L.; Dixon, L.K. African swine fever: A re-emerging viral disease threatening the global pig industry. Vet. J. 2018, 233, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, L.K.; Sun, H.; Roberts, H. African swine fever. Antivir. Res. 2019, 165, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, Q.; Shao, L.; Xiang, Y. Structural Insights into the Assembly of the African Swine Fever Virus Inner Capsid. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e00268-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salas, M.L.; Andrés, G. African swine fever virus morphogenesis. Virus Res. 2013, 173, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galindo, I.; Alonso, C. African Swine Fever Virus: A Review. Viruses 2017, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, L.K.; Chapman, D.A.; Netherton, C.L.; Upton, C. African swine fever virus replication and genomics. Virus Res. 2013, 173, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D.A.; Darby, A.C.; Da Silva, M.; Upton, C.; Radford, A.D.; Dixon, L.K. Genomic analysis of highly virulent Georgia 2007/1 isolate of African swine fever virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabarés, E.; Olivares, I.; Santurde, G.; Garcia, M.J.; Martin, E.; Carnero, M.E. African swine fever virus DNA: Deletions and additions during adaptation to growth in monkey kidney cells. Arch. Virol. 1987, 97, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, R.; Agüero, M.; Almendral, J.M.; Viñuela, E. Variable and constant regions in African swine fever virus DNA. Virology 1989, 168, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumption, K.J.; Hutchings, G.H.; Wilkinson, P.J.; Dixon, L.K. Variable regions on the genome of Malawi isolates of African swine fever virus. J. Gen. Virol. 1990, 71, 2331–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Vega, I.; Viñuela, E.; Blasco, R. Genetic variation and multigene families in African swine fever virus. Virology 1990, 179, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, M.; Tian, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, J.; Yang, S.; Chen, Y.; et al. The African swine fever virus gene MGF_360-4L inhibits interferon signaling by recruiting mitochondrial selective autophagy receptor SQSTM1 degrading MDA5 antagonizing innate immune responses. mBio 2025, 16, e0267724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunney, J.K.; Fang, Y.; Ladinig, A.; Chen, N.; Li, Y.; Rowland, B.; Renukaradhya, G.J. Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus (PRRSV): Pathogenesis and Interaction with the Immune System. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2016, 4, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Pulido, D.; Boley, P.A.; Ouma, W.Z.; Alhamo, M.A.; Saif, L.J.; Kenney, S.P. Comparative Transcriptome Profiling of Human and Pig Intestinal Epithelial Cells After Porcine Deltacoronavirus Infection. Viruses 2021, 13, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Niu, G.; Yang, L.; Ji, W.; Zhang, L.; Ren, L. PCV2 and PRV Coinfection Induces Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress via PERK-eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP and IRE1-XBP1-EDEM Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrascosa, A.L.; Santaren, J.F.; Vinuela, E. Production and titration of African swine fever virus in porcine alveolar macrophages. J. Virol. Methods 1982, 3, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Duan, X.; Ren, J.; Zhang, J.; Guan, G.; Ru, Y.; Li, D.; Zheng, H. African Swine Fever Virus I267L Is a Hemorrhage-Related Gene Based on Transcriptome Analysis. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S.; Kawashima, S.; Okuno, Y.; Hattori, M. The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, D277–D280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.I.; Sheet, S.; Bui, V.N.; Dao, D.T.; Bui, N.A.; Kim, T.H.; Cha, J.; Park, M.R.; Hur, T.Y.; Jung, Y.H.; et al. Transcriptome profiles of organ tissues from pigs experimentally infected with African swine fever virus in early phase of infection. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2366406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, Z.; Guan, G.; Luo, J.; Yin, H.; Niu, Q. OAS1 suppresses African swine fever virus replication by recruiting TRIM21 to degrade viral major capsid protein. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e0121723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Y.M.; Pichlmair, A.; Górna, M.W.; Superti-Furga, G.; Nagar, B. Structural basis for viral 5′-PPP-RNA recognition by human IFIT proteins. Nature 2013, 494, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.Q.; Cai, M.P.; Wang, M.Y.; Shi, B.W.; Yang, G.Y.; Wang, J.; Chu, B.B.; Ming, S.L. Pseudorabies virus manipulates mitochondrial tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase 2 for viral replication. Virol. Sin. 2024, 39, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample Name | RNA Concentration (ng/µL) | RIN Value | Sample Grade |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mock6–1 | 207.3 | 9.74 | A |

| Mock6–2 | 212.2 | 9.52 | A |

| Mock6–3 | 233.3 | 9.72 | A |

| AW6–1 | 178.6 | 9.71 | A |

| AW6–2 | 242.9 | 9.70 | A |

| AW6–3 | 202.8 | 9.71 | A |

| AC6–1 | 170.2 | 9.38 | A |

| AC6–2 | 208.0 | 9.69 | A |

| AC6–3 | 220.8 | 9.68 | A |

| Mock16–1 | 182.4 | 9.53 | A |

| Mock16–2 | 209.7 | 9.72 | A |

| Mock16–3 | 189.0 | 9.72 | A |

| AW16–1 | 178.7 | 9.68 | A |

| AW16–2 | 203.8 | 9.69 | A |

| AW16–3 | 183.9 | 9.28 | A |

| AC16–1 | 171.2 | 9.69 | A |

| AC16–2 | 208.1 | 9.16 | A |

| AC16–3 | 178.0 | 9.03 | A |

| Sample Name | ≥Q30 (%) | GC Content (%) | Clean Reads | Mapped Reads (%) | Unique Mapped Reads (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mock6–1 | 96.25 | 50.48 | 33,044,634 | 96.12 | 93.34 |

| Mock6–2 | 96.28 | 50.65 | 29,106,984 | 96.07 | 93.35 |

| Mock6–3 | 96.09 | 50.82 | 33,290,771 | 95.88 | 93.09 |

| Mock16–1 | 96.07 | 51.05 | 31,606,949 | 95.92 | 93.13 |

| Mock16–2 | 96.11 | 51.20 | 28,476,041 | 95.66 | 92.71 |

| Mock16–3 | 96.21 | 50.64 | 29,694,705 | 96.12 | 93.32 |

| AW6–1 | 96.23 | 51.03 | 31,892,470 | 94.55 | 91.67 |

| AW6–2 | 96.07 | 51.13 | 29,008,431 | 94.15 | 91.30 |

| AW6–3 | 96.42 | 49.89 | 24,006,120 | 94.47 | 91.76 |

| AW16–1 | 96.11 | 50.05 | 24,403,020 | 95.05 | 92.31 |

| AW16–2 | 95.95 | 50.85 | 25,739,922 | 92.49 | 89.56 |

| AW16–3 | 96.45 | 50.13 | 28,090,758 | 94.77 | 91.98 |

| AC6–1 | 96.68 | 50.65 | 30,000,168 | 95.10 | 92.25 |

| AC6–2 | 96.21 | 50.80 | 26,211,255 | 94.25 | 91.53 |

| AC6–3 | 96.25 | 50.49 | 33,012,588 | 94.83 | 92.04 |

| AC16–1 | 96.93 | 50.87 | 38,409,071 | 94.52 | 91.45 |

| AC16–2 | 96.54 | 51.39 | 30,568,378 | 94.14 | 91.20 |

| AC16–3 | 96.32 | 51.16 | 31,033,817 | 93.78 | 90.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Zhao, P.; Huang, Y.; Tao, C.; Jia, H. Transcriptomic Analysis of MGF360–4L Mediated Regulation in African Swine Fever Virus-Infected Porcine Alveolar Macrophages. Animals 2025, 15, 3029. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203029

Wang Z, Zhu L, Zhao P, Huang Y, Tao C, Jia H. Transcriptomic Analysis of MGF360–4L Mediated Regulation in African Swine Fever Virus-Infected Porcine Alveolar Macrophages. Animals. 2025; 15(20):3029. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203029

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhen, Liqi Zhu, Peng Zhao, Ying Huang, Chunhao Tao, and Hong Jia. 2025. "Transcriptomic Analysis of MGF360–4L Mediated Regulation in African Swine Fever Virus-Infected Porcine Alveolar Macrophages" Animals 15, no. 20: 3029. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203029

APA StyleWang, Z., Zhu, L., Zhao, P., Huang, Y., Tao, C., & Jia, H. (2025). Transcriptomic Analysis of MGF360–4L Mediated Regulation in African Swine Fever Virus-Infected Porcine Alveolar Macrophages. Animals, 15(20), 3029. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203029