Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) Inferred by mtDNA and Y-Chromosomal Genes

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

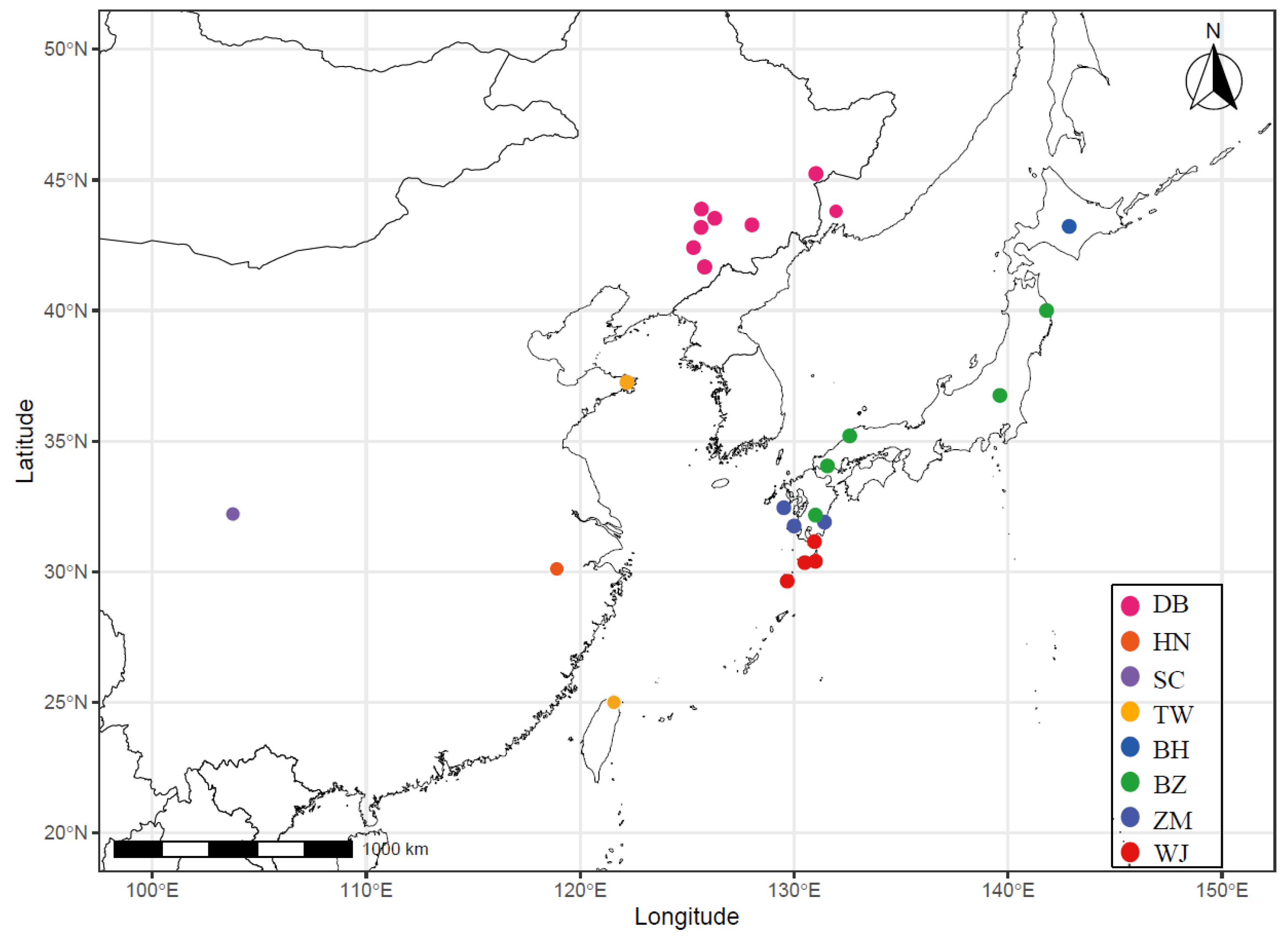

2.1. Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

2.2. Primer Design and Synthesis

2.3. PCR Amplification and Sequencing

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

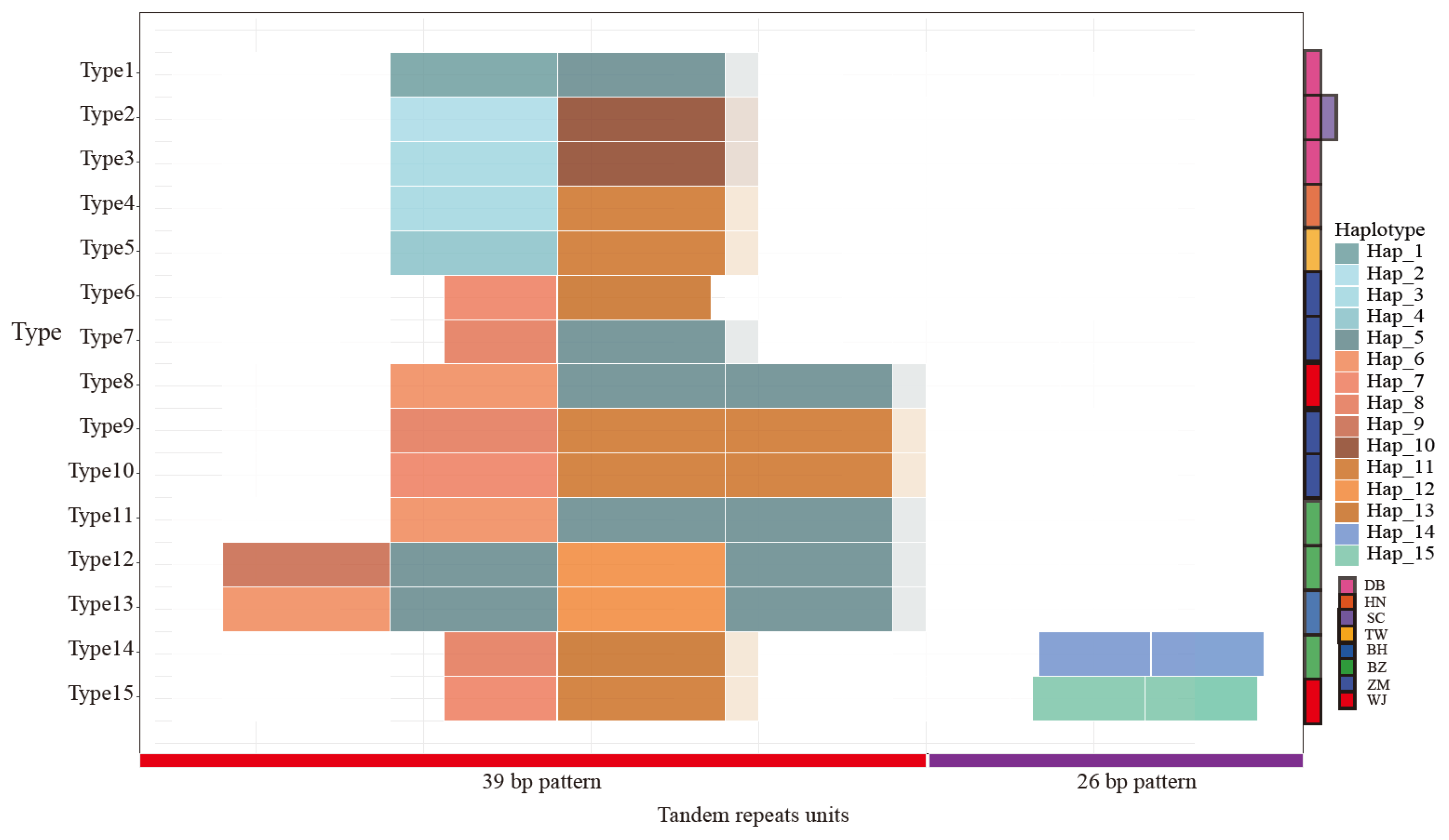

3.1. Different Patterns of Tandem Repeat Sequences

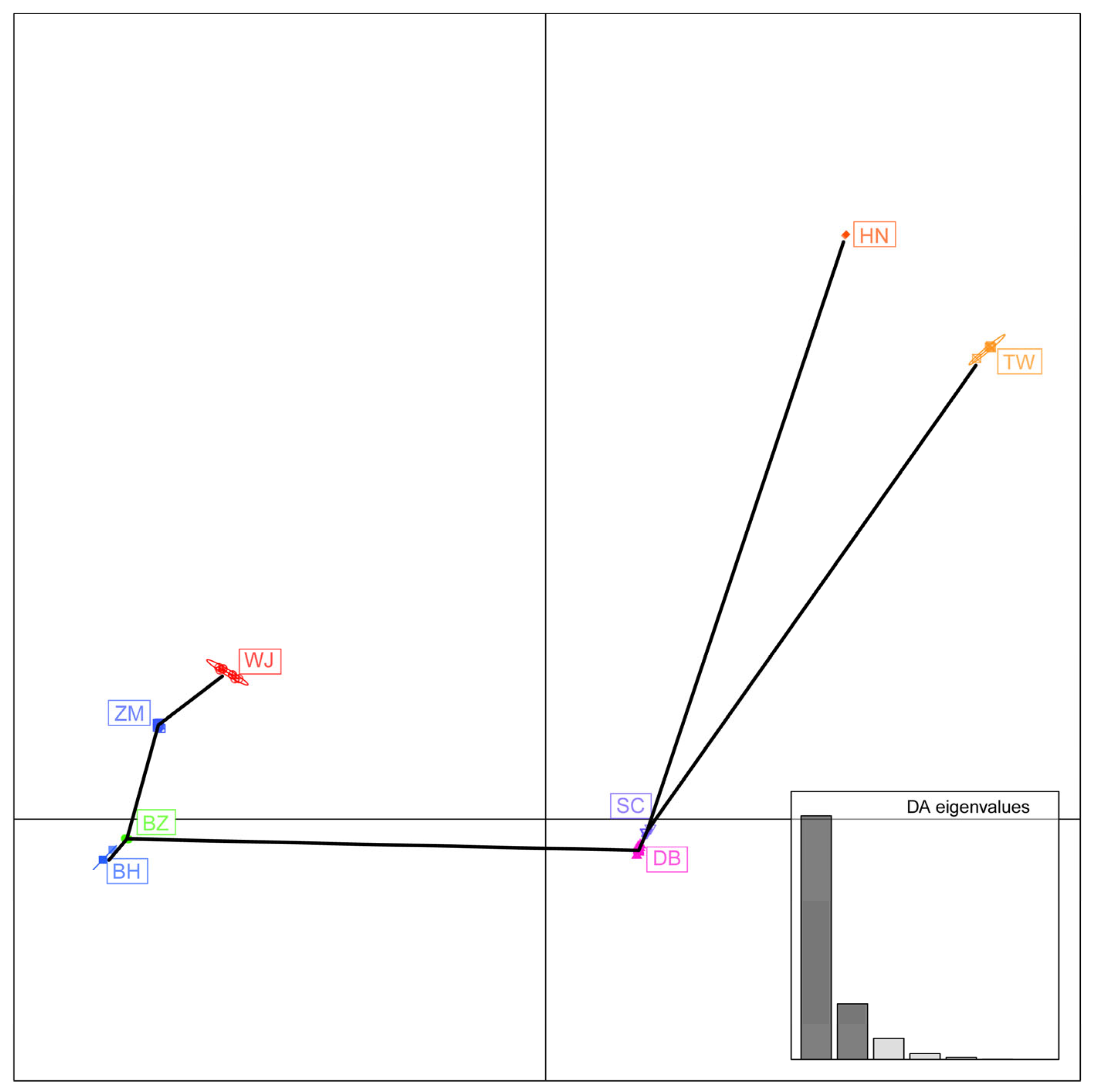

3.2. Genetic Diversity of Mitochondrial Protein-Coding Genes

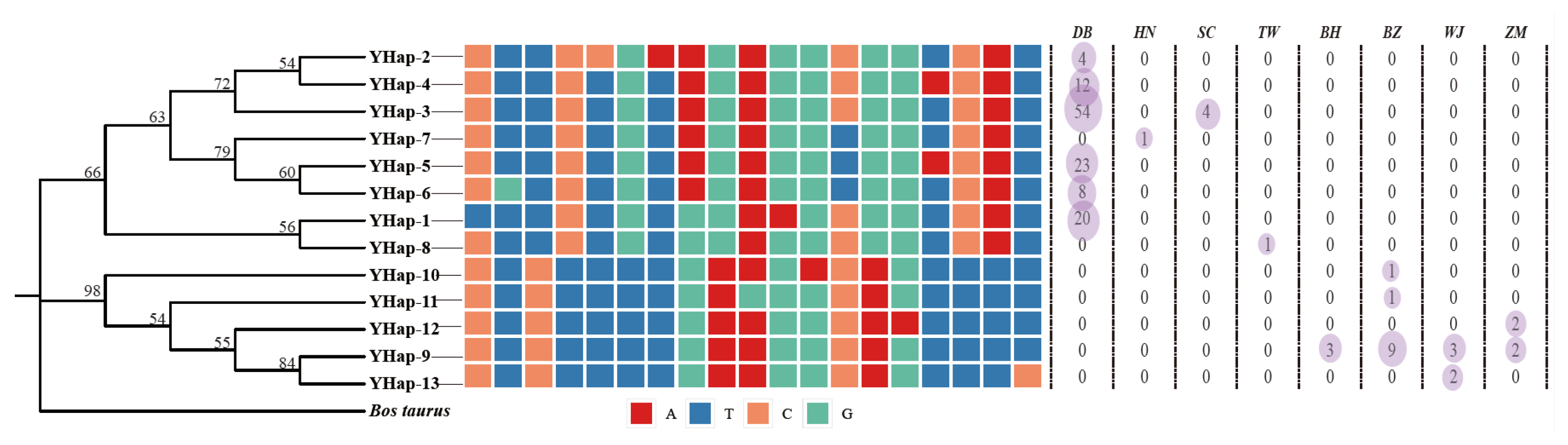

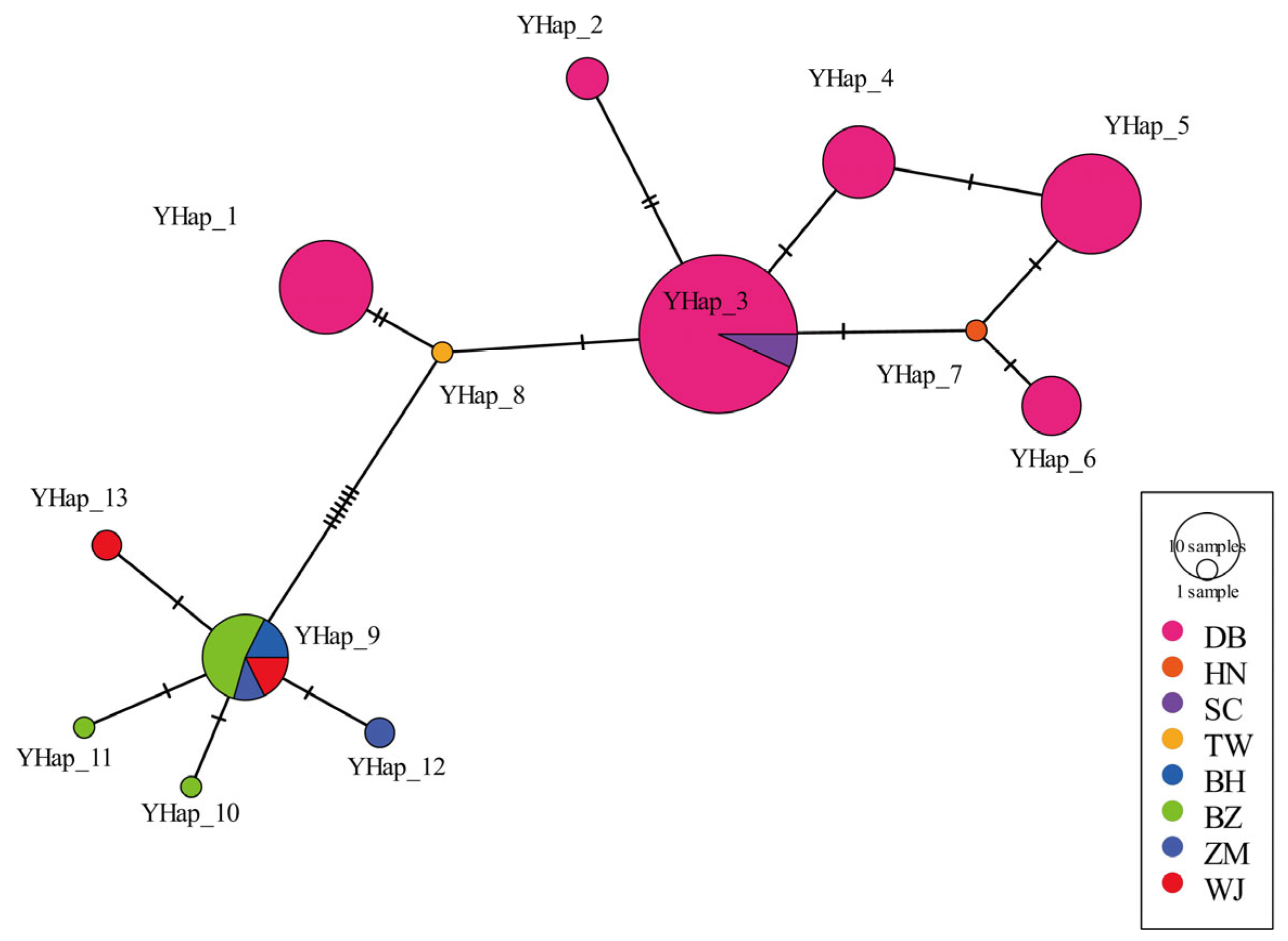

3.3. Genetic Diversity of Y-Chromosome Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CR | Control Region |

| DAPC | Discriminant Analysis of Principal Components |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| PCG | Protein-Coding Gene |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SNP | Single Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| TR | Tandem Repeat |

| TRU | Tandem Repeat Unit |

| PIC | Polymorphism Information Content |

References

- Harris, R.B. Cervus nippon. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; International Union for Conservation of Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 2015; e.T41788A22155877. [CrossRef]

- Ohtaishi, N.; Gao, Y. A review of the distribution of all species of deer (Tragulidae, Moschidae and Cervidae) in China. Mammal Rev. 1990, 20, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, J.; Masuda, R.; Kaji, K.; Kaneko, M.; Yoshida, M.C. Genetic variation and population structure of the Japanese sika deer (Cervus nippon) in Hokkaido Island, based on mitochondrial D-loop sequences. Mol. Ecol. 1998, 7, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Doormaal, N.; Ohashi, H.; Koike, S.; Kaji, K. Influence of human activities on the activity patterns of Japanese sika deer (Cervus nippon) and wild boar (Sus scrofa) in Central Japan. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2015, 61, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Wang, D.; Cui, Y.; Huang, F.; Liu, Y.; Dai, J.; Wu, W.; Dai, Z.; Xie, J.; Zhu, X.; et al. Diet, nutrient characteristics and gut microbiome between summer and winter drive adaptive strategies of East China sika deer (Cervus nippon kopschi) in the Yangtze River basin. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, B.; Wang, T.; Dong, Y.; Ju, Y.; Li, Y.; Su, W.; Zhang, R.; Dong, S.; Wang, H.; et al. Population genomics of sika deer reveals recent speciation and genetic selective signatures during evolution and domestication. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takatsuki, S. Effects of sika deer on vegetation in Japan: A review. Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 1922–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukada, H.; Ishikawa, K.; Shimizu, N. Damage to round bale silage caused by sika deer (Cervus nippon) in central Japan. Grassl. Sci. 2012, 58, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Study on the performance of the velvet antler of Sika Deer). Chin. J. Anim. Sci. 2003, 39, 31–32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tamate, H.B.; Tatsuzawa, S.; Suda, K.; Izawa, M.; Doi, T.; Sunagawa, K.; Miyahira, F.; Tado, H. Mitochondrial DNA Variations in Local Populations of the Japanese Sika Deer Cervus nippon. J. Mammal. 1998, 79, 1396–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.P.; Wei, F.W.; Li, M. Genetic diversity of Chinese sika deer (Cervus nippon) and its systematic relationship with Japanese sika deer). Chin. Sci. Bull. 2006, 3, 292–298. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Wan, Q.H.; Fang, S.G. Two genetically distinct units of the Chinese sika deer (Cervus nippon): Analyses of mitochondrial DNA variation. Biol. Conserv. 2004, 119, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, J.; Masuda, R.; Tamate, H.B.; Hamasaki, S.-I.; Ochiai, K.; Asada, M.; Tatsuzawa, S.; Suda, K.; Tado, H.; Yoshida, M.C. Two genetically distinct lineages of the sika deer, Cervus nippon, in Japanese islands: Comparison of mitochondrial D-loop region sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1999, 13, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, J. Two Genetically Distinct Lineages of the Japanese Sika Deer Based on Mitochondrial Control Regions; Springer: Osaka, Japan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ba, H.; Wu, L.; Liu, Z.; Li, C. An examination of the origin and evolution of additional tandem repeats in the mitochondrial DNA control region of Japanese sika deer (Cervus nippon). Mitochondrial DNA 2014, 27, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, K.; Hoshi, A.; Nojima, R.; Suzuki, K.; Takiguchi, H.; Takatsuki, S.; Takizawa, T.; Hosoi, E.; Tamate, H.B.; Hayashida, M.; et al. Genetic Variation in Y-Chromosome Genes of Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) in Japan. Zool. Sci. 2020, 37, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F.; Queirós, S.; Gusmão, L.; Nijman, I.J.; Cuppen, E.; Lenstra, J.A.; Consortium, E.; Davis, S.J.; Nejmeddine, F.; Amorim, A. Tracing the history of goat pastoralism: New clues from mitochondrial and Y chromosome DNA in North Africa. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2009, 26, 2765–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, O.; Ojeda, A.; Tomàs, A.; Gallardo, D.; Huang, L.; Folch, J.; Clop, A.; Sanchez, A.; Badaoui, B.; Hanotte, O.; et al. Integrating Y-chromosome, mitochondrial, and autosomal data to analyze the origin of pig breeds. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2009, 26, 2061–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidon, T.; Janke, A.; Fain, S.R.; Eiken, H.G.; Hagen, S.B.; Saarma, U.; Hallström, B.M.; LeComte, N.; Hailer, F. Brown and polar bear Y chromosomes reveal extensive male-biased gene flow within brother lineages. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014, 31, 1353–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Liu, H.; Zhang, R.; Ju, Y.; Su, W.; Tamate, H.; Xing, X. Complete mitochondrial genome and phylogenetic analysis of eight sika deer subspecies in northeast Asia. J. Genet. 2022, 101, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.; Lee, A. Sequence analysis using DNAMAN. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Sanderford, M.; Sharma, S.; Tamura, K. MEGA12: Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis Version 12 for Adaptive and Green Computing. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, G.; Lohman, D.J.; Meier, R. SequenceMatrix: Concatenation software for the fast assembly of multi-gene datasets with character set and codon information. Cladistics 2011, 27, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA Sequence Polymorphism Analysis of Large Data Sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PopArt. Available online: http://popart.otago.ac.nz (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Clement, M.; Snell, Q.; Walker, P.; Posada, D.; Crandall, K.A. TCS: Estimating gene genealogies. Parallel Distrib. Process. Symp. Int. Proc. 2002, 2, 184. [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier, L.; Lischer, H.E.L. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: A new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2010, 10, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: A program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jombart, T. adegenet: A R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 1403–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Sun, X.; Shen, J.; Gao, F.; Qiu, G.; Wang, T.; Nie, X.; Zhang, W.; Gao, Y.; Bai, Y. Molecular Evolutionary Analysis of Potato Virus Y Infecting Potato Based on the VPg Gene. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štohlová Putnová, L.; Štohl, R.; Ernst, M.; Svobodová, K. A Microsatellite Genotyping-Based Genetic Study of Interspecific Hybridization between the Red and Sika Deer in the Western Czech Republic. Animals 2021, 11, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalb, D.M.; Delaney, D.A.; DeYoung, R.W.; Bowman, J.L. Genetic diversity and demographic history of introduced sika deer on the Delmarva Peninsula. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 11504–11517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.N. Analysis of Maternal and Paternal Types of Stud Sika Deer Based on Mitochondrial DNA and Y Chromosome Gene Fragments. Master’s Thesis, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Science, Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Borowski, Z.; Świsłocka, M.; Matosiuk, M.; Mirski, P.; Krysiuk, K.; Czajkowska, M.; Borkowska, A.; Ratkiewicz, M. Purifying Selection, Density Blocking and Unnoticed Mitochondrial DNA Diversity in the Red Deer, Cervus elaphus. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabata, D.; Masuda, R.; Takahashi, O. Bottleneck effects on the sika deer Cervus nippon population in Hokkaido, revealed by ancient DNA analysis. Zool. Sci. 2004, 21, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, S.J.; Tamate, H.B.; Wilson, R.; Nagata, J.; Tatsuzawa, S.; Swanson, G.M.; Pemberton, J.M.; McCullough, D.R. Bottlenecks, drift and differentiation: The population structure and demographic history of sika deer (Cervus nippon) in the Japanese archipelago. Mol. Ecol. 2001, 10, 1357–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petr, M.; Hajdinjak, M.; Fu, Q.; Essel, E.; Rougier, H.; Crevecoeur, I.; Semal, P.; Golovanova, L.V.; Doronichev, V.B.; Lalueza-Fox, C.; et al. The evolutionary history of Neanderthal and Denisovan Y chromosomes. Science 2020, 369, 1653–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.Q. Study on the Origin of Chinese Domestic Horses Based on Genetic Variations of Y-Chromosome. Ph.D. Thesis, China Agricultural University, Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Population Name | Subspecies | Type | Region * | Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DB (213) | C. n. hortulorum | Domesticated | Dongfeng, Jilin | 35 |

| Changchun, Jilin | 31 | |||

| Xingkai Lake, Heilongjiang | 35 | |||

| Siping, Jilin | 31 | |||

| Shuangyang, Jilin | 33 | |||

| Dunhua, Jilin | 17 | |||

| Tonghua, Jilin | 30 | |||

| DB (5) | C. n. hortulorum | Wild | Ussuriysk | 5 |

| HN (4) | C. n. kopschi | Wild | Qingliangfeng, Zhejiang | 4 |

| SC (9) | C. n. sichuanicus | Wild | Tiebu, Sichuan | 9 |

| TW (4) | C. n. taiouanus | Wild | Taipei, Taiwan | 2 |

| Weihai, Shandong | 2 | |||

| BH (7) | C. n. yesoensis | Wild | Ashoro, Hokkaido | 7 |

| BZ (29) | C. n. centralis | Wild | Goyozan, Honshu | 6 |

| Shimane, Honshu | 5 | |||

| Yamaguchi, Honshu | 9 | |||

| Tsushima, Tsushima | 5 | |||

| Nikko, Honshu | 4 | |||

| WJ (11) | C. n. yakushimae | Wild | Tanegashima, Tanegashima | 3 |

| Yakushima, Yakushima | 6 | |||

| Miyanoura, Yakushima | 1 | |||

| Yoshida, Yakushima | 1 | |||

| ZM (21) | C. n. nippon | Wild | Miyazaki, Kyushu | 10 |

| Sata, Kagoshima/Kyushu | 3 | |||

| Nagasaki, Kyushu | 8 |

| Population | Size * | Count | Hd (±SE) | π (±SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DB | 217 | 38 | 0.700 (±0.015) | 0.00624 (±0.0002) |

| HN | 4 | 3 | 0.833 (±0.111) | 0.00022 (±4 × 10−5) |

| SC | 5 | 4 | 0.900 (±0.072) | 0.00063 (±7.60 × 10−5) |

| TW | 4 | 4 | 1.000 (±0.089) | 0.00053 (±7.5 × 10−5) |

| BH | 5 | 2 | 0.400 (±0.106) | 0.00014 (±3.58 × 10−5) |

| BZ | 25 | 5 | 0.793 (±0.009) | 0.01018 (±0.0004) |

| WJ | 9 | 6 | 0.889 (±0.030) | 0.00636 (±0.0004) |

| ZM | 21 | 10 | 0.910 (±0.008) | 0.00329 (±5.02 × 10−5) |

| Total | 290 | 72 | 0.917 (±0.000) | 0.01430 (±4.58 × 10−5) |

| Population | DB | HN | SC | TW | BH | BZ | WJ | ZM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAD1 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| NAD2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| COX1 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| COX2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ATP8 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ATP6 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| COX3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| NAD3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NAD4L | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NAD4 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| NAD5 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| NAD6 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| CYTB | 0 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 1 | 28 | 36 | 40 | 5 | 0 | 14 | 0 |

| Populations | DB | HN | SC | TW | BH | BZ | WJ | ZM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DB | ||||||||

| HN | 0.00874 | |||||||

| SC | 0.01254 | 0.01187 | ||||||

| TW | 0.01353 | 0.01271 | 0.01032 | |||||

| BH | 0.03012 | 0.03074 | 0.03065 | 0.03199 | ||||

| BZ | 0.02983 | 0.02945 | 0.03055 | 0.03103 | 0.01984 | |||

| WJ | 0.01254 | 0.03205 | 0.03316 | 0.03381 | 0.02904 | 0.01354 | ||

| ZM | 0.03256 | 0.02916 | 0.03093 | 0.03119 | 0.02637 | 0.00953 | 0.00917 |

| DB | HN | SC | TW | BH | BZ | WJ | ZM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DB | ||||||||

| HN | 0.00041 | |||||||

| SC | 0.00020 | 0.00020 | ||||||

| TW | 0.00041 | 0.00041 | 0.00020 | |||||

| BH | 0.00183 | 0.00183 | 0.00162 | 0.00142 | ||||

| BZ | 0.00189 | 0.00188 | 0.00168 | 0.00148 | 0.00007 | |||

| WJ | 0.00191 | 0.00185 | 0.00164 | 0.00144 | 0.00005 | 0.00011 | ||

| ZM | 0.00193 | 0.00186 | 0.00166 | 0.00145 | 0.00010 | 0.00017 | 0.000015 | |

| Hd * | 0.728 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.345 | 0.600 | 0.667 |

| π | 0.00038 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00007 | 0.00012 | 0.00014 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, T.; Dong, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Su, W.; Xing, X. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) Inferred by mtDNA and Y-Chromosomal Genes. Animals 2025, 15, 3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203022

Wang T, Dong Y, Wang L, Liu H, Su W, Xing X. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) Inferred by mtDNA and Y-Chromosomal Genes. Animals. 2025; 15(20):3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203022

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Tianjiao, Yimeng Dong, Lei Wang, Huamiao Liu, Weilin Su, and Xiumei Xing. 2025. "Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) Inferred by mtDNA and Y-Chromosomal Genes" Animals 15, no. 20: 3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203022

APA StyleWang, T., Dong, Y., Wang, L., Liu, H., Su, W., & Xing, X. (2025). Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) Inferred by mtDNA and Y-Chromosomal Genes. Animals, 15(20), 3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203022