Turtles for Sale: Species Prevalence in the Pet Trade in Poland and Potential Introduction Risks

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

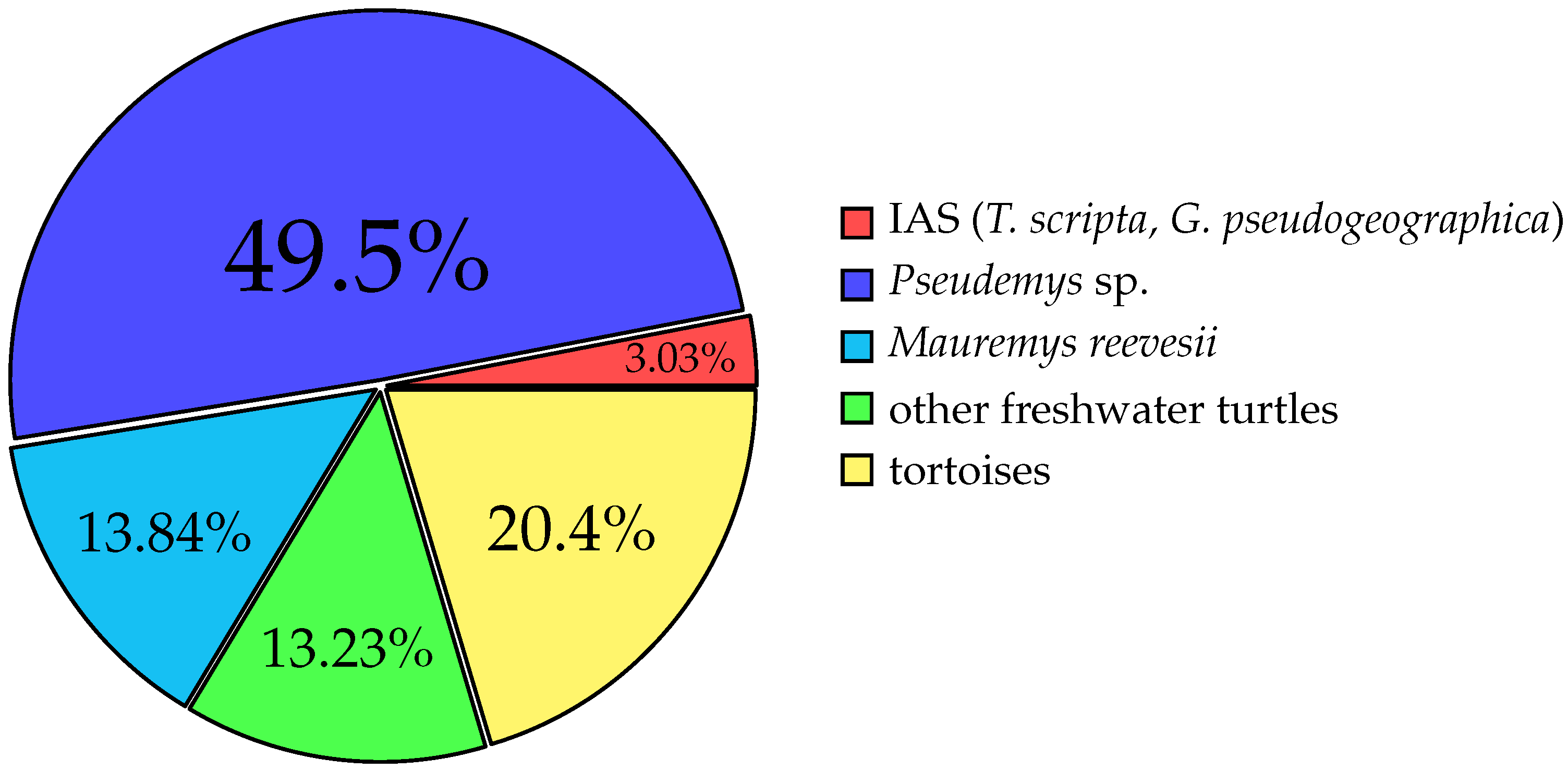

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haines, A.M.; Costante, D.M.; Freed, C.; Achayaraj, G.; Bleyer, L.; Emeric, C.; Fenton, L.A.; Lielbriedis, L.; Ritter, E.; Salerni, G.I.; et al. The impact of invasive alien species on threatened and endangered species: A geographic perspective. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2024, 48, e1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, J.L.; Welbourne, D.J.; Romagosa, C.M.; Cassey, P.; Mandrak, N.E. When pets become pests: The role of the exotic pet trade in producing invasive vertebrate animals. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 17, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesay, R.E.V.; Sesay, F.; Azizi, M.I.; Rahmani, B. Invasive Species and Biodiversity: Mechanisms, Impacts, and Strategic Management for Ecological Preservation. Asian J. Environ. Ecol. 2024, 23, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research & Markets. North America & Europe Exotic Companion Animal Market—Industry Outlook and Forecast 2024–2029. 2024. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5998824/north-america-europe-exotic-companion-animal (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Bush, E.R.; Baker, S.E.; Macdonald, D.W. Global trade in exotic pets 2006–2012. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 28, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente, M.F.; de Araủjo, B.M.C.; da Silva Policarpo, I.; Pereira, H.M.; Martins Borges, A.K.; Vieira, W.L.S.; Alves, R.R.N. Keeping reptiles as pets in Brazil: Keepers’ motivations and husbandry practices. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2023, 21, 19–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw, R. Scales and Tails: The Welfare and Trade of Reptiles Kept as Pets in Canada; World Society for the Protection of Animals: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2005; Available online: https://www.zoocheck.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Reptile_Report_FA.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Hollandt, T.; Baur, M.; Wöhr, A. Animal-appropriate housing of ball pythons (Python regius)—Behavior-based evaluation of two types of housing systems. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CITES Trade Database. Annual Trade Report Statistics—Live Turtles; Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. 2024. Available online: https://trade.cites.org (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Sung, Y.H.; Lee, W.H.; Leung, F.K.W.; Fong, J.J. Prevalence of illegal turtle trade on social media and implications for wildlife trade monitoring. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 261, 109245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Wan, A.K.Y.; Chen, Z.; Clark, A.; Court, C.; Gu, Y.; Park, T.; Reynolds, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; et al. Use of consumer insights to inform behavior change interventions aimed at illegal pet turtle trade in China. Conserv. Biol. 2024, 38, e14352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simberloff, D.; Martin, J.-L.; Genovesi, P.; Maris, V.; Wardle, D.A.; Aronson, J.; Courchamp, F.; Galil, B.; García-Berthou, E.; Pascal, M.; et al. Impacts of biological invasions: What’s what and the way forward. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2013, 28, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament & Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) No1143/2014 of 22 October 2014 on the prevention and management of the introduction and spread of invasive alien species. Off. J. Eur. Union 2014, L317, 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Thunberg, C.P. [Testudo scripta]. In Historia Testudinum Iconibus Illustrata; Schoepff, J.D., Ed.; Ioannis Iacobi Palm: Erlangen, Germany, 1792; pp. 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Linnaeus, C. Systema Naturae, per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, Cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis. Tomus I. Editio Decima, Reformata; Laurentius Salvius: Stockholm, Sweden, 1758. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, J.G. Allgemeine Naturgeschichte der Schildkröten: Nebst einem systematischen Verzeichnisse der einzelnen Arten und zwey Kupfern; J. G. Müller: Erlangen, Germany, 1783; pp. 1–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.E. Synopsis Reptilium: Or Short Descriptions of the Species of Reptiles. Part I—Cataphracta. Tortoises, Crocodiles, and Enaliosaurians; Treuttel, Wurz and Co.: London, UK, 1831; pp. 29–73. [Google Scholar]

- Act of 11 August 2021 on Alien Species. Dz. Ustaw (J. Laws Repub. Pol.) 2021, item 1718. Available online: https://dziennikustaw.gov.pl/DU/2021/1718 (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Simberloff, D. Biological invasions: What’s worth fighting and what can be won? Ecol. Eng. 2014, 65, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.E. Catalogue of Shield Reptiles in the Collection of the British Museum. Part I—Testudinata (Tortoises); British Museum: London, UK, 1855; pp. 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J.E. Characters of several new species of freshwater tortoises (Emys) India China. Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1834, 2, 53–54. [Google Scholar]

- Latreille, P. A. Histoire Naturelle des Reptiles, avec figures dessinées d’après nature. Tome Premier. Première Partie. Quadrupèdes et Bipèdes Ovipares; Imprimerie de Crapelet: Paris, France, 1801; pp. 1–280. [Google Scholar]

- Agassiz, L. Contributions to the Natural History of the United States of America. First Monograph. Vol. I. Part II. North American Testudinata; Little, Brown and Co.: Boston, MA, USA, 1857; Volume I, p. 436. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnaterre, P.J.; Bénard, R.; Panckoucke, C.J. Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la nature; Chez Panckoucke: Paris, France, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lacépède, B.G.E. Histoire Naturelle des Quadrupèdes Ovipares et des Serpens. Tome Premier; Hôtel de Thou: Paris, France, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagler, J.G. Natürliches System der Amphibien: Mit vorangehender Classification der Säugethiere und Vögel, ein Beitrag zur vergleichenden Zoologie; J. G. Cotta’sche Buchhandlung: Stuttgart, Germany, 1830; pp. 1–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweigger, A.F. Prodromus monographiae Cheloniorum. Königsberg. Arch. Naturwiss. Math. 1812, 1, 314. [Google Scholar]

- Cope, E.D. Third contribution to the herpetology of tropical America. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phila. 1865, 17, 185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegmann, A.F.A. Beiträge zur Zoologie, gesammelt auf einer Reise um die Erde von Dr. F. J. F. Meyen. Siebente Abhandlung. Amphibien. Nova Acta Phys.-Med. Acad. Caesareae Leopold.-Carol. Naturae Curiosorum 1835, 17, 183–268. [Google Scholar]

- Krefft, G. Notes on Australian animals in New Guinea with description of a new species of freshwater tortoise belonging to the genus Euchelymys (Gray). Ann. Mus. Civ. Stor. Nat. Genova 1876, 1, 390–394. [Google Scholar]

- Siebenrock, F. Über zwei seltene und eine neue Schildkröte des Berliner Museums. Sitzungsber. Kais. Akad. Wiss. Wien Math.-Naturwiss. Kl. 1903, 112, 439–445. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J.E. A Synopsis of the Species of the Class Reptilia. In The Animal Kingdom Arranged in Conformity with Its Organization, by the Baron Cuvier, with Additional Descriptions of All the Species Hitherto Named, and of Many Not Before Noticed; Griffith, E., Pidgeon, E., Eds.; Whittaker, Treacher and Co.: London, UK, 1830; Volume 9, pp. 1–110. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.F. Icones Animalium et Plantarum. Various Subjects of Natural History, Wherein Are Delineated Birds, Animals, and Many Curious Plants; Letterpress: London, UK, 1779; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, T. Descriptions of three new species of land tortoises. Zool. J. 1828, 3, 419–421. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J.E. Catalogue of the Tortoises, Crocodiles, and Amphisbænians in the Collection of the British Museum; Edward Newman: London, UK, 1844. [Google Scholar]

- Gmelin, J.F. Caroli a Linné Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae: Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, Cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis; Georg. Emanuel Beer: Leipzig, Germany, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoepff, J.D. Historia Testudinum Iconibus Illustrata; Ioannis Iacobi Palm: Erlangen, Germany, 1792; pp. 1–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Spix, J.B. Animalia nova sive species novae testudinum et ranarum: Quas in itinere per Brasiliam annis 1817–1820 jussu et auspiciis Maximiliani Josephi I. Bavariae regis suscepto, collegit et descripsit Dr. J. B. de Spix; F. S. Hübschmanni: Munich, Germany, 1824; pp. 1–53. Available online: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/21828 (accessed on 20 April 2025).[Green Version]

- Fitzinger, L.J. Entwurf einer systematischen Anordnung der Schildkröten nach den Grundsätzen der natürlichen Methode. Ann. Mus. Wien 1835, 1, 103–128. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Jackson, T.G.; Nelson, D.H.; Morris, A.B. Phylogenetic Relationships in the North American Genus Pseudemys (Emydidae) Inferred Two Mitochondrial Genes. Southeast. Nat. 2012, 11, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinks, P.Q.; Thomson, R.C.; Pauly, G.B.; Newman, C.E.; Mount, G.; Shaffer, H.B. Misleading phylogenetic inferences based on single-exemplar sampling in the turtle genus Pseudemys. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013, 68, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.; Martínez-Silvestre, A.; Martins, J.J. Are the invasive species Trachemys scripta and Pseudemys concinna able to reproduce in the northern coast of Portugal? In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Freshwater Turtles Conservation, Vila Nova de Gaia, Portugal, 22–24 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri, V.; Battisti, C.; Soccini, C.; Santoro, R. A hotspot of xenodiversity: First evidence of an assemblage of non-native freshwater turtles in a suburban wetland in Central Italy. Lakes Reserv. 2020, 25, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kala, B.; Gorzkowski, B.; Solarz, W. Harmonia+PL—Procedura oceny ryzyka negatywnego oddziaływania inwazyjnych i potencjalnie inwazyjnych gatunków obcych w Polsce: Trachemys scripta; General Directorate for Environmental Protection: Warsaw, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Marini, D.; Chlebicka, N.; Gorzkowski, B.; Wasyl, D. Alien freshwater turtle diversity in Eastern Poland: Live-trapping and clinical examination. In Proceedings of the II Congresso Nazionale Testuggini e Tartarughe SHI (Societas Herpetologica Italica), Albenga, Italy, 11–13 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Radulski, Ł.; Krajewska-Wędzina, M.; Lipiec, M.; Winer, M.; Zabost, A.; Augustynowicz-Kopeć, E. Mycobacterial Infections in Invasive Turtle Species in Poland. Pathogens 2023, 12, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, R.; Ye, Z.; Shi, H. Habitat selection and home range of Reeves’ turtle (Mauremys reevesii) Qichun County, Hubei Province China. Animals 2023, 13, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, C. Free-ranging Mauremys reevesii (Gray, 1831), Family Geoemydidae, in North-Western Spain: The First of Many in Europe? Braña 2016, 14, 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- Parham, J.F.; Papenfuss, T.J.; Sellas, A.B.; Stuart, B.L.; Simison, W.B. Genetic variation and admixture of red-eared sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans) in the USA. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2020, 145, 106722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, S.; Browne, M.; Boudjelas, S. 100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species; IUCN SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG): Gland, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Badziukiewicz, J.; Wróblewski, P.; Maciaszek, R. Obce gatunki żółwi na rynku zoologicznym w Polsce. In Funkcjonowanie populacji zwierząt dzikich i towarzyszących w zmieniających się uwarunkowaniach środowiskowych i prawnych; Karpiński, M., Flis, M., Czyżowski, P., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego w Lublinie: Lublin, Poland, 2024; pp. 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najbar, B. The red-eared slider turtle Trachemys scripta Lubus. Region. Przegląd Zool. 2001, 45, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Rzeżutka, A.; Kaupke, A.; Gorzkowski, B. Detection of Cryptosporidium parvum in a Red-Eared Slider Turtle (Trachemys scripta elegans), a Noted Invasive Alien Species, Captured in a Rural Aquatic Ecosystem in Eastern Poland. Acta Parasitol. 2020, 65, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindeman, P.V. Growth curves for Graptemys, with a Comparison to Other Emydid Turtles. Am. Midl. Nat. 1999, 142, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kala, B.; Gorzkowski, B.; Mazurska, K. Harmonia+PL—Procedura oceny ryzyka negatywnego oddziaływania inwazyjnych i potencjalnie inwazyjnych gatunków obcych w Polsce: Graptemys pseudogeographica; General Directorate for Environmental Protection: Warsaw, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament & Council of the European Union. Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora. Off. J. Eur. Union 1992, L206, 7–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cadi, A.; Joly, P. The introduction of the slider turtle (Trachemys scripta elegans) in Europe: Competition for basking sites with the European pond turtle (Emys orbicularis). In Proceedings of the IInd International Symposium on Emys orbicularis, Le Blanc, France, 25–27 June 1999; Volume 2, pp. 95–97. [Google Scholar]

- Goławska, O.; Wiśniecka, M.; Gorzkowski, B.; Zając, M.; Soleniec, D.; Śmiałowska, A.; Wasyl, D. Do we have to be afraid of bacteria from invasive and alien turtles? In Proceedings of the Joint EAZWV/AAZV Conference, Prague, Czech Republic, 6–12 October 2018; pp. 211–213. [Google Scholar]

- Jungwirth, N.; Bodewes, R.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Baumgärtner, W.; Wohlsein, P. First report of a new alphaherpesvirus in a freshwater turtle Pseudemys concinna kept in Germany. Vet. Microbiol. 2014, 170, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönbächler, K.; Olias, P.; Richard, O.K.; Origgi, F.C.; Dervas, E.; Hoby, S.; Basso, W.; Berenguer Veiga, I. Fatal spirorchiidosis in European pond turtles Emys orbicularis in Switzerland. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2022, 17, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, S.; Wimalasena, M.P.; De Zoysa, M.; Heo, G.-J. Prevalence of Citrobacter Spp. from Pet Turtles and Their Environment. J. Exot. Pet Med. 2017, 26, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopecký, O.; Kalous, L.; Patoka, J. Establishment risk from pet-trade freshwater turtles in the European Union. Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst. 2013, 410, 02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, G.-R.; Roques, A.; Hulme, P.E.; Sykes, M.T.; Pyšek, P.; Kühn, I.; Zobel, M.; Bacher, S.; Botta-Dukát, Z.; Bugmann, H.; et al. Alien species in a warmer world: Risks and opportunities. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009, 24, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Collected | Description | Unit/Data Type | Possible Options/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Website address | URL of the website where the listing was found | Text (URL) | |

| Archived offer file name | File name of the saved listing archive | Text | |

| Date of finding and posting | Date when the listing was found and posted | Date (YYYY-MM-DD) | |

| Listing status | Whether the listing is currently active or inactive | Categorical | Active/Inactive |

| Vernacular (common) name used | Common name of the turtle used in the listing | Text | |

| Scientific name used | Scientific name used in the listing | Text | |

| Corrected scientific name | Corrected/validated scientific name | Text | |

| Number of individuals | Number of turtles offered | Integer | |

| Specimen type | Age or life stage of specimens offered | Categorical | Juvenile/Adult/ Unspecified |

| Distinctive traits | Any notable features or morphs described | Text | |

| Unit type | Type of sales unit (per individual, per group, etc.) | Text | Individual/Group |

| Price per unit (PLN) | Price per unit in Polish zloty | Numeric (PLN) | |

| Additional comments | Extra notes provided by seller | Text | |

| Sale conditions | Conditions or terms of sale | Text | |

| Seller type | Type of seller | Categorical | Private individual/ Commercial seller |

| Seller name or company name | Name of seller or company | Text | |

| E-mail address | Contact email | Text | |

| Phone number | Contact phone number | Text | |

| Voivodeship/Region | Seller’s region or voivodeship | Text | |

| Other contact details | Additional contact information | Text | |

| Notes from direct contact | Notes from any direct communication with the seller | Text |

| Species or Higher Taxa | English Name | Total Observations | Fairs | Pet Shops | Online Private | Online Companies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freshwater turtles | 788 | 517 | 58 | 149 | 64 | |

| Pseudemys sp. [20] | Pseudemys, cooter, hieroglyphic turtle * | 490 | 394 | 14 | 58 | 24 |

| Mauremys reevesii [17] | Chinese pond turtle | 137 | 63 | 30 | 29 | 15 |

| Mauremys sinensis [21] | Chinese stripe-necked turtle | 70 | 28 | 12 | 15 | 15 |

| Trachemys scripta [14] | Pond slider | 27 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 0 |

| Trachemys venusta [20] | Meso-American slider | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Sternotherus odoratus [22] | Common musk turtle | 22 | 8 | 0 | 11 | 3 |

| Graptemys pseudogeographica [17] | False map turtle | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Graptemys sp. [23] | Map turtles | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Pelomedusa subrufa [24,25] | African helmeted turtle | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Pelomedusa sp. [26] | Pelomedusa | 27 | 24 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Pelusios castaneus [27] | West African mud turtle | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Claudius angustatus [28] | Narrow-bridged musk turtle | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Pelodiscus sinensis [29] | Chinese softshell turtle | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Apalone ferox [16] | Florida softshell turtle | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Emydura subglobosa [30] | Red-bellied short-necked turtle | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Tortoises | 202 | 42 | 36 | 88 | 36 | |

| Malacochersus tornieri [31] | Pancake tortoise | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Kinixys belliana [32] | Bell’s hinge-back tortoise | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Centrochelys sulcata [33] | African spurred tortoise | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Stigmochelys pardalis [34] | Leopard tortoise | 9 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| Testudo horsfieldii [35] | Russian tortoise | 70 | 11 | 24 | 20 | 15 |

| Testudo hermanni [36] | Hermann’s tortoise | 55 | 12 | 11 | 25 | 7 |

| Testudo marginata [37] | Marginated tortoise | 26 | 12 | 0 | 11 | 3 |

| Testudo graeca [15] | Greek tortoise | 14 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 3 |

| Testudo sp. [15] | Mediterranean tortoises | 12 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 5 |

| Chelonoidis carbonarius [38] | Red-footed tortoise | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Chelonoidis sp. [39] | Chelonoidis | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| All turtles and tortoises | 990 | 559 | 94 | 237 | 100 | |

| Source | Total observations | Fairs | Pet shops | Online private | Online companies | |

| N % | N % | N % | N % | N % | ||

| Number of improperly labelled offers | 218 22 | 70 13 | 19 20 | 96 39 | 32 31 | |

| Species | Carapace Length of Adult Turtle (cm) | Lifespan (Years) | Minimum Enclosure Size | Basking Temp (°C) | Water | Lighting | Average Cost of a Turtle (USD) * | Price per Set (USD) ** | Average Cost per Month (USD) *** | Average Cost per Year (USD) *** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. scripta (IAS) | 15–35 | 30–40 | 100 × 60 × 45 cm, ≥380 L | 26–37 | 24–26 °C, strong filtration | UVB, heat lamp, 12–14 h | 92.5 | 320 | 30 | 360 |

| Pseudemys spp. | 23–43 | 30–40 | 200 × 120 × 45 cm, 300–400 L | 28–36 | 25–28 °C, strong filtration | UVB, heat lamp, 12–13 h | 55 | 450 | 30 | 360 |

| G. pseudogeographica (IAS) | 15–30 | >30 | 100 × 50 × 50 cm, ≥115 L | 27–32 | 22–25 °C, strong filtration | UVB, heat lamp, 10–14 h | 21.5 | 320 | 35 | 480 |

| M. reevesii | 11–24 | >24 | 80 × 40 × 40 cm, 100–150 L | 32–35 | 20–26 °C, strong filtration | UVB, heat lamp, 12–14 h | 53 | 180 | 30 | 360 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Badziukiewicz, J.; Bors, M.; Maciaszek, R.; Świderek, W. Turtles for Sale: Species Prevalence in the Pet Trade in Poland and Potential Introduction Risks. Animals 2025, 15, 2711. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15182711

Badziukiewicz J, Bors M, Maciaszek R, Świderek W. Turtles for Sale: Species Prevalence in the Pet Trade in Poland and Potential Introduction Risks. Animals. 2025; 15(18):2711. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15182711

Chicago/Turabian StyleBadziukiewicz, Jakub, Milena Bors, Rafał Maciaszek, and Wiesław Świderek. 2025. "Turtles for Sale: Species Prevalence in the Pet Trade in Poland and Potential Introduction Risks" Animals 15, no. 18: 2711. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15182711

APA StyleBadziukiewicz, J., Bors, M., Maciaszek, R., & Świderek, W. (2025). Turtles for Sale: Species Prevalence in the Pet Trade in Poland and Potential Introduction Risks. Animals, 15(18), 2711. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15182711