Intellectual Property Protection of New Animal Breeds in China: Theoretical Justification, International Comparison, and Institutional Construction

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Methods

1.3.1. Literature Analysis

1.3.2. Normative Analysis

1.3.3. Comparative Analysis

2. Theoretical Justification of Intellectual Property Protection for New Animal Breeds in China

2.1. Definition and Scope of New Animal Breeds

2.1.1. Definition Standard for New Animal Breeds

2.1.2. Differences Between New Animal Breeds and New Plant Varieties

2.2. The Necessity of Intellectual Property Protection for New Animal Breeds

2.3. The Particularities of Intellectual Property Protection for New Animal Breeds

3. International Comparison of Intellectual Property Protection for New Animal Breeds in China

3.1. Protection Model of Granting Patent Rights to New Animal Breeds

3.1.1. United States: Distinguishing “Artificial” from “Natural”

3.1.2. European Union: Dynamically Balancing Technological Innovation and Ethics

3.2. Protection Model of Granting Patent Rights to Methods of Breeding New Animal Breeds

3.2.1. Canada: Technology-Oriented Indirect Protection

3.2.2. Japan: Limited Protection with Inconsistency Between Legislation and Practice

3.3. Protection Model of Granting the Rights in New Animal Breeds

3.4. Comparative Analysis of Intellectual Property Protection Models for New Animal Breeds

3.4.1. Comparison of the Advantages and Disadvantages of Intellectual Property Protection Models for New Animal Breeds

3.4.2. Expected Benefits of the Sui Generis Protection Model for New Animal Breeds in China

4. Institutional Construction of Intellectual Property Protection for New Animal Breeds in China

4.1. Normative Construction for the Rights in New Animal Breeds

4.1.1. Subjects of the Rights in New Animal Breeds

4.1.2. Contents of the Rights in New Animal Breeds

4.1.3. Limitations on the Rights in New Animal Breeds

4.2. Top-Level Design for the Rights in New Animal Breeds

4.2.1. Enacting Specialized Legislation

4.2.2. Clarifying Procedure for Acquiring Rights

4.3. Ethical Review for the Rights in New Animal Breeds

4.3.1. Animal Welfare Review

4.3.2. Genetic Information Review

4.4. Security Evaluation for Rights in New Animal Breeds

4.4.1. Food Security Evaluation

4.4.2. Environmental Security Evaluation

4.5. Risk Balancing for Rights in New Animal Breeds

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, B.; Choudhary, A.; Chauhan, R. Intellectual property rights in animal biotechnology. Adv. Anim. Biotechnol. 2019, 1, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Bandyopadhyay, S. Animal biotechnology and intellectual property rights: A comprehensive analysis. Uttar Pradesh J. Zool. 2024, 45, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. The current status and improvement directions of legal rules regarding Chinese national gene banks for farm animal genetic resources. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1413625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaffney, J.; Tibebu, R.; Bart, R.; Beyene, G.; Girma, D.; Kane, N.A.; Mace, E.S.; Mockler, T.; Nickson, T.E.; Taylor, N.; et al. Open access to genetic sequence data maximizes value to scientists, farmers, and society. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 26, 100411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Pray, C.; Zhang, W. Effectiveness of intellectual property protection: Survey evidence from China. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2012, 41, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lai, X. Do innovation incentive policies affect China’s agricultural patent: Based on the perspective of different R&D subjects. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 7237–7256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budolfson, M.; Fischer, B.; Scovronick, N. Animal welfare: Methods to improve policy and practice. Science 2023, 381, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxley, H.S.; Szydlowski, M.; Hill, K.; Hooper, J. Rethinking animal welfare in a globalised world: Cultural perspectives, challenges, and future directions. Animals 2025, 15, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunes, M.C.; Osório-Santos, Z.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G.; Hötzel, M.J. Gene Editing for Improved Animal Welfare and Production Traits in Cattle: Will This Technology Be Embraced or Rejected by the Public? Sustainability 2021, 13, 4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Allocation of burden of proof in infringement litigation of new plant varieties. Intellect. Prop. 2023, 4, 45–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, D.; Sun, H.; Yang, Y. Research on the object boundary of transgenic biotechnology intellectual property. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2009, 26, 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Guinan, F.L.; Wiggans, G.R.; Norman, H.D.; Dürr, J.W.; Cole, J.B.; Van Tassell, C.P.; Misztal, I.; Lourenco, D. Changes in genetic trends in US dairy cattle since the implementation of genomic selection. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 1110–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnachie, E.; Hötzel, M.J.; Robbins, J.A.; Shriver, A.; Weary, D.M.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G. Public attitudes towards genetically modified polled cattle. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazariuc, C.; Lozovanu, E. Intellectual Property in the Context of Global Ethics. East. Eur. J. Reg. Stud. 2021, 7, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zeng, J. International experience and Chinese model of biosafety legal governance. Acad. Circ. 2024, 3, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research Group of Institute of Industrial and Technological Economics of National Development and Reform Commission; Ren, W.; Qiu, L. Protection of trade secrets and industrial innovation development: Mechanisms, challenges and strategies. Macroecon. Res. 2024, 2, 106–115+127. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Sun, M.X.; Yu, Q.; Ye, W.J.; Liu, X.; Du, X.Z. Review of research ethics in life sciences. Acta Ed. 2024, 36, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Fu, J.; Wang, L. Development and Application of Laboratory Animal Ethics Management System in University Scientific Research Management: Taking Zhejiang University as an Example. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2023, 43, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Code. 35 U.S.C. § 101. Available online: https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/consolidated_laws.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Diamond v. Chakrabarty, 447 U.S. 303 (1980), 310. Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/447/303/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Li, Y. The fate of the Harvard Mouse: Trends of international patent protection and China’s choices. Sci. Technol. Law 2006, 2, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B. Comparative study of plant and animal patent protection systems between China and the United States. World Agric. 2017, 7, 83–89+244. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z. Intellectual property protection of plant and animal varieties. Intellect. Prop. 1995, 3, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ass’n for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, 569 U.S. 576 (2013). Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/569/576/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Moore, K.; Frederickson, R. Strong Roots: Comparative Analysis of Patent Protection for Plants and Animals. Available online: https://ipwatchdog.com/2020/08/05/strong-roots-comparative-analysis-patent-protection-animals-plants/id=123649/# (accessed on 24 July 2020).

- In re Roslin Institute (Edinburgh), 750 F.3d 1333 (Fed. Cir. 2014). Available online: https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/cafc/13-1407/13-1407-2014-05-08.html (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Reid, B.C. A Practical Guide to Patent Law, 2nd ed.; Sweet & Maxwell: London, UK, 1993; pp. 1–350. [Google Scholar]

- Boards of Appeal of the European Patent Office. Case Law of the Boards of Appeal of the European Patent Office, 6th ed.; China Patent Agent (Hong Kong) Ltd., Translator; Intellectual Property Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council. Directive 98/44/EC on the Legal Protection of Biotechnological Inventions. Off. J. Eur. Communities 1998, L213, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament of the Council on Plants Obtained by Certain New Genomic Techniques and Their Food and Feed, and Amending Regulation; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Woźniak-Gientka, E.; Tyczewska, A. Genome editing in plants as a key technology in sustainable bioeconomy. EFB Bioecon. J. 2023, 3, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.F.; Yang, F.; Liu, X.X. Theoretical proof, international comparison and Chinese approach for gene edited food labeling system. Biotechnol. Bull. 2025, 41, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, F. Comparative Legal Perspectives on Ethical and Legal Governance Models for Laboratory Animals: With Reflections on the Relationship Between Laboratory Animal Law and the Animal Protection Legal System with Chinese Characteristics. Law Rev. 2021, 39, 148–158. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council. Directive 2010/63/EU of 22 September 2010 on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes, Articles 20, 26, 34, 36–41. Off. J. Eur. Union 2010, L276, 33–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.Y. The Construction of Ethical Review System of Science and Technology in China’ s Patent Examination. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2025, 42, 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Canada Patent Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. P-4. Available online: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/p-4/index.html (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Harvard College v. Canada (Commissioner of Patents), [1998] 3 F.C. 529 (F.C.T.D.). Available online: https://reports.fja-cmf.gc.ca/fja-cmf/j/en/item/332325/index.do (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Harvard College v. Canada (Commissioner of Patents), [2000] 4 F.C. 528 (F.C.A.). Available online: https://www.canlii.org/en/ca/fca/doc/2000/2000canlii16058/2000canlii16058.html?resultId=e272a19efef24a77b7595b759de2233a&searchId=2025-08-16T13:49:23:464/4bef4f077b5c4532b706633c6c2a6df5 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Harvard College v. Canada (Commissioner of Patents), [2002] 4 S.C.R. 45, 2002 SCC 76. Available online: https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/2019/1/document.do (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Canadian Intellectual Property Office (CIPO). Examination Practice in Biotechnology; CIPO: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Patent Act, Act No. 121 of 1959. Available online: https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/en/laws/view/4097 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Liu, X.; Geng, N. Development Trend of Intellectual Property Protection of Genetically Modified Organisms in the United States, Japan and European Union and the Inspiration to China. Intellect. Prop. 2011, 1, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Patent Office. Examination Guidelines in Life Sciences; Japan Patent Office: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Patent Attorneys Association (JPAA). Opinion on Patentability of Genetically Modified Animals. JPAA. 2024. Available online: https://www.jpaa.or.jp/en/ip-information/patent-others/#faq (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Law on the Protection of New Varieties of Plants and Animals (SG No. 84/1996, as Amended on 23 December 2022). Bulgaria. Available online: https://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/ (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Li, J. Research on Bulgaria’s Intellectual Property Protection System under the “Belt and Road” Initiative. J. Law 2018, 39, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Law on the Protection of New Varieties of Plants and Animals (SG No. 84/1996, as Amended on 23 December 2022). Bulgaria. Available online: https://www.mzh.government.bg/media/filer_public/2020/06/10/zakon_za_zhivotnovdstvoto.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Regulations on the Organization and Activity of the Commission for Recognition of Breeding Organizations, Approval of Breeding Programmes and on Permits for Breeding Activities; Bulgaria. Available online: https://www.mzh.government.bg/media/filer_public/2020/06/25/pravilnik_za_organizatsiiata_i_deinostta_na_komisiiata.docx (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Regulation on the Organization and Operation of the National Committee for Animal Genetic Resources; Bulgaria. Available online: https://www.mzh.government.bg/media/filer_public/2021/01/20/01_pismo_do_vnositel_za_publikuvane_proekt_na_pravilnik_nsgrj_-_za_30102020.docx (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Agricultural Report 2024; Ministry of Agriculture, Republic of Bulgaria: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2024. Available online: https://www.mzh.government.bg/media/filer_public/2025/01/16/ad_2024_en.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- European Regional Focal Point for Animal Genetic Resources (ERFP). Exciting Seminar on the European Animal Genetic Resources Strategy Held in Sofia! ERFP. 2023. Available online: https://www.animalgeneticresources.net (accessed on 4 June 2025).

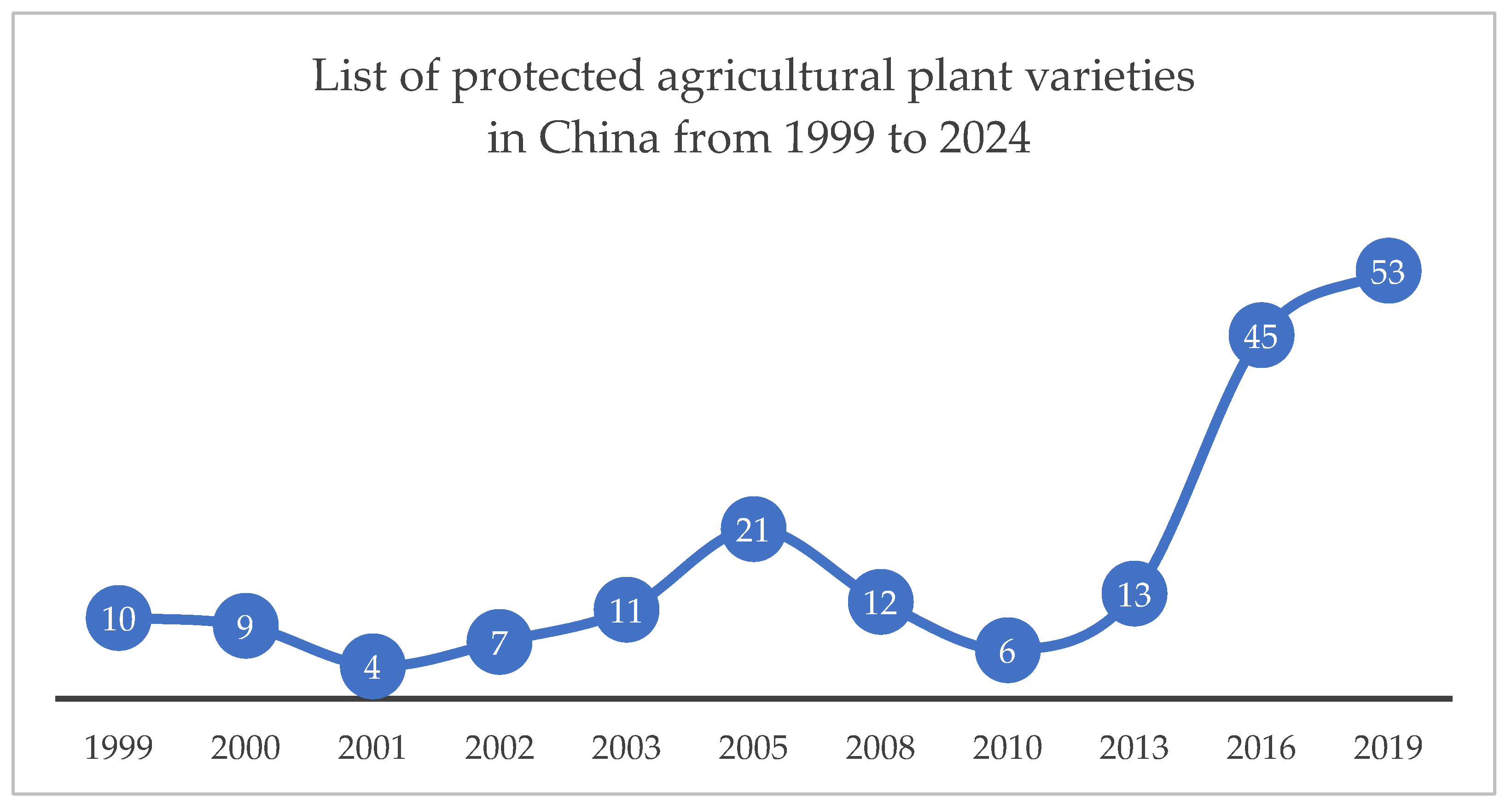

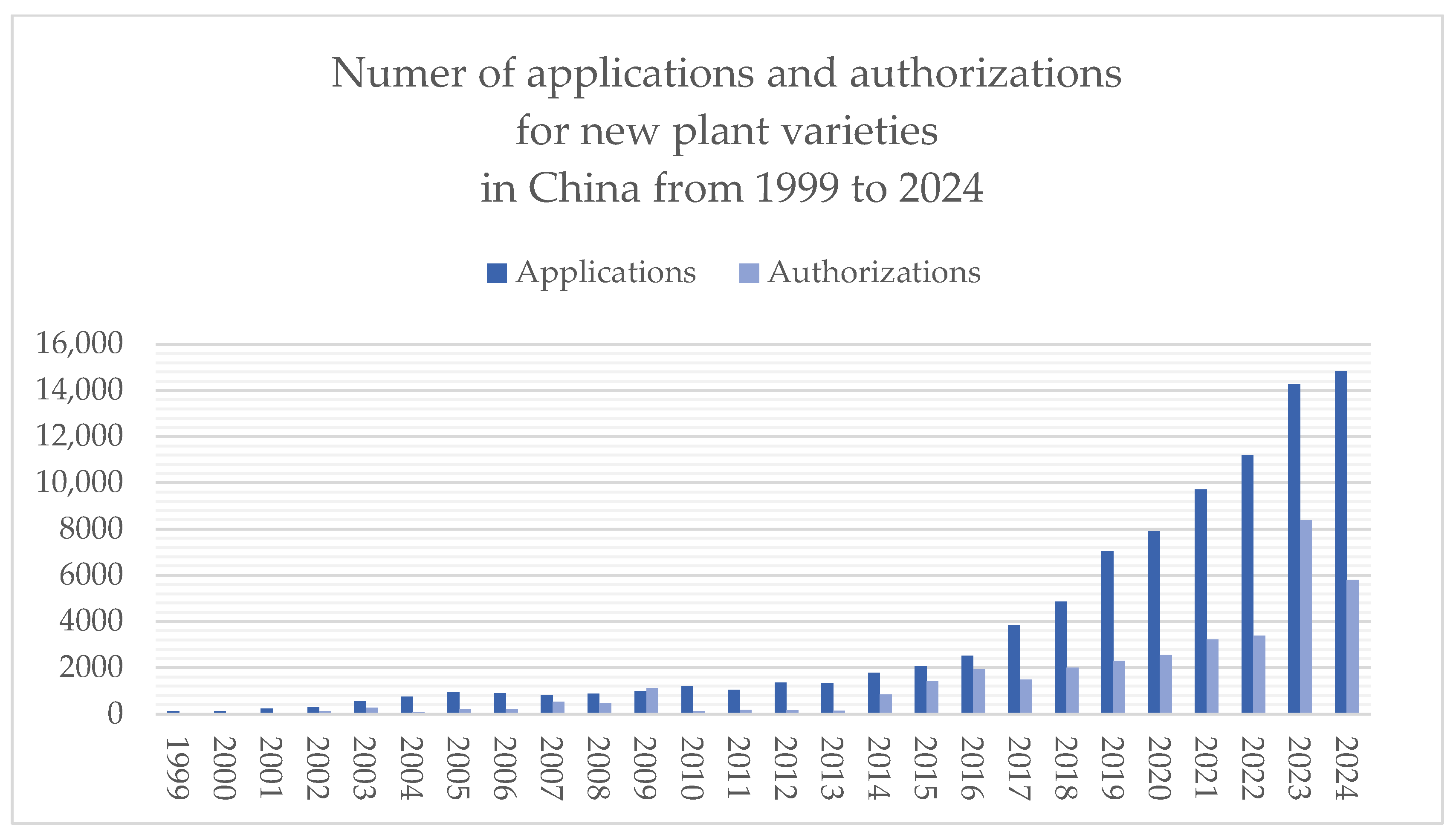

- Jiang, G.B. Analysis of status and development trend on the protection of new agricultural plant varieties in China. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2025, 27, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.K. Legislative Draft Proposal of the “Law of the Protection of Rights to New Animal Breeds in People’ s Republic of China”; Intellectual Property Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2017; p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Global Plan of Action for Animal Genetic Resources and the Interlaken Declaration. In Proceedings of the International Technical Conference on Animal Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, Interlaken, Switzerland, 3–7 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- UK Government. Genetic Technology (Precision Breeding) Act 2023. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2023/6/contents/enacted (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Ma, W.N.; Chen, Y.P.; Han, F.Q. Ethical Governance of Science and Technology: Core Meaning, Dilemma and Implementation Mechanism. Forum Sci. Technol. China 2024, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernyhough, M.; Nicol, C.J.; van de Braak, T.; Toscano, M.J. The Ethics of Laying Hen Genetics. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2019, 33, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, L.A.; Conneely, M.; Kennedy, E.; O’Connell, N.; O’Driscoll, K.; Earley, B. Animal Welfare Research—Progress to Date and Future Prospects. Ir. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 61, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Statistics Authority. Data Ethics. Available online: https://uksa.statisticsauthority.gov.uk/what-we-do/data-ethics/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Song, Y.; Huo, Z.; Deng, Y. Research on UK Governance System of Science and Technology Ethics and Implication. Forum Sci. Technol. China 2024, 179–188. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.13580/j.cnki.fstc.2024.08.012 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Nie, C.-H.; Wan, S.-M.; Chen, Y.-L.; Huysseune, A.; Wu, Y.-M.; Zhou, J.-J.; Hilsdorf, A.W.S.; Wang, W.-M.; Witten, P.E.; Lin, Q.; et al. Single-Cell Transcriptomes and runx2b−/− Mutants Reveal the Genetic Signatures of Intermuscular Bone Formation in Zebrafish. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2022, 9, nwac152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Shi, S.; Li, X.; Zhai, G. Biosafety Assessment and Management of Genome Editing Assisted Breeding of Fish. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 2025, 49, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Li, X.; Yang, G.; Shi, X. Development Status of Genetically Modified Animals and Their Safety Evaluation in China. Chin. J. Vet. Med. 2018, 54, 62–64. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K.E.; Allen, B.L.; Berger-Tal, O.; Fidler, F.; Garrard, G.E.; Hampton, J.O.; Lean, C.H.; Parris, K.M.; Sherwen, S.L.; White, T.E.; et al. Explicit value trade-offs in conservation: Integrating animal welfare. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2025, 40, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, N. Adapting legal regimes: Ensuring access, equity, and protection of genetic resources in Chinese aquaculture. Aquaculture 2025, 600, 742245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, R.A.; Mark, A.L. Who’s patenting what? An empirical exploration of patent prosecution. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2000, 6, 2099–2174. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.F.; Wan, Z.Q. Identification of employee breeding and its distribution of rights and interests from the perspective of labor relation. Priv. Law Rev. 2023, 46, 131–147. [Google Scholar]

- Martyniuk, E. Policy effects on the sustainability of animal breeding. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Institutional Element | New Plant Varieties | New Animal Breeds |

|---|---|---|

| Legislative Status | Administrative regulation: “Regulations on Protection of New Plant Varieties” (promulgated in 1997, recently revised in 2025) | No dedicated legislation yet; existing norms scattered across documents such as the “Animal Husbandry Law” |

| Types of Rights | Plant variety rights, falling under the category of sui generis intellectual property | A dedicated protection system for new animal breeds yet to be established; needs to define the nature of rights |

| Examination Standards | DUS criteria: distinctness, uniformity, stability, and novelty | Refer to the DUS framework; need to adapt to the genetic characteristics of animals and explore appropriate evaluation methods |

| Granting Authority | Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, National Forestry and Grassland Administration | No dedicated granting authority yet; new animal variety registration is under the Seed Management Department, typically affiliated with agricultural or livestock departments |

| Application Procedure | Application → preliminary examination → public notice → substantive examination → grant of rights | Specialized examination and granting procedures need to be developed to improve the transparency and professionalism of review |

| Term of Protection | 25 years for vines, forest trees, fruit trees, and ornamental trees; 20 years for other plant varieties | Refer to the plant system: proposed protection period of 30 years, with extended protection for specific high-value traits |

| Scope of Rights | Includes production, reproduction, processing, sale, import, and export within the industry chain | Specific rights need to be defined and codified through legislation |

| Types of Infringement and Remedies | Unauthorized reproduction, sale, and use; civil, administrative, and criminal remedies available | Requires clarification of infringement types and corresponding civil liability and administrative enforcement mechanisms |

| Ethical and Public Interest Regulations | No explicit ethical review mechanism, recent efforts have strengthened ecological impact assessments | Establish ethical evaluation procedures to balance animal welfare with biotechnological innovation |

| International Regulatory Framework | Member of UPOV 1978 Convention | Should align with UPOV framework, referencing international treaties, conventions, and benefit-sharing guidelines such as those under the Nagoya Protocol |

| Country/Region and Legal Basis | Criteria for New Animal Breeds | Intellectual Property Protection Model for New Animal Breeds | Other Relevant Provisions or Measures | Legal and Regulatory Requirements Related to Animal Welfare and Animal Ethics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA U.S. Patent Law, Transgenic Animal Patent Reform Act | Novelty, utility, non-obviousness | Patent rights for new animal breeds | (1) Involves genetic modification; requires FDA or USDA approval (2) Exemption for farmers: users who unknowingly infringe on patented animals may be exempt from liability | The Animal Welfare Act and Animal Welfare Regulation guarantee the humane treatment of animals in the process of experimental research, commercial transportation, pet exhibitions, etc. |

| EU The European Patent Convention (EPC), Directive 98/44/EC | Substantive differences, novelty, inventiveness, industrial applicability | Patent rights for the method of breeding; the animal itself may not always be patentable | Emphasis on public order and ethical considerations | Directive 2010/63/EU, emphasis is placed on animal welfare protection for laboratory animals |

| Japan Patent Act, Examination Guidelines | Novelty, inventiveness, industrial applicability | Patent rights for the method; the animal itself is generally not patentable | Only methods for producing animals are eligible for patent protection; genetically modified animals may not be protected under patent law | (1) Welfare and Management of Animals Act clarifies that animal keepers should protect the health, safety, and natural behavior of animals (2) Animal Protection and Management Act clearly stipulates the 3R principle of laboratory animals and other related content |

| Bulgaria Plant and Animal Variety Protection Act | Novelty, inventiveness, utility; technical effects subject to certain limitations | Animal breed rights granted | The protection system includes a registration and examination process; domestic breeding products may be protected through national procedures | Animal Protection Act guarantees the humane treatment of animals in their rearing, breeding, training, and commercial use |

| Canada Patent Act | Novelty not defined for animal breeds | Methods for breeding animals may be patentable, not the animal itself | The Public Health Agency of Canada is responsible for reviewing the genetic components of animal breeds | (1) The Criminal Code forbids any person from intentionally causing neglect, suffering, or injury of an animal (2) The CFIA regulates the humane transportation and humane treatment of animals in federal slaughterhouses |

| UK Genetic Technology (Precision Breeding) Act | Biotechnology characteristics (e.g., human-made deletions, natural mutations, precise breeding) | Patent rights for breeding techniques, not animals themselves | Set up a DEFRA regulatory mechanism and a Genetic Technology Committee (GTC) to handle approvals and ethical reviews. Implement a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) system to assess the ethics of genetic data | Applicants are required to make an animal welfare declaration before obtaining a license for the sale of precision-bred animals |

| Protection Mode | Representative Country/Region | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Granting Patent Rights to New Animal Breed | USA EU | Highly exclusive Highly motivating Conductive to transforming results | Confusing structure Significant social and ethical controversy Low social acceptance |

| Granting Patent Rights to Methods of Breeding New Animal Breeds | Canada Japan | Highly operational Integrates easily into existing systems Avoids social and ethical controversies | Indirect protection Easy to replicate Insufficient incentives |

| Granting the Rights in New Animal Breeds | Bulgaria Czech Republic | Clear system structure Strong exclusivity Adequate incentives Promotes the transformation of results Low social and ethical risk | High database construction requirements Low social acceptance |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, W.; Chen, X. Intellectual Property Protection of New Animal Breeds in China: Theoretical Justification, International Comparison, and Institutional Construction. Animals 2025, 15, 2411. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15162411

Zhang W, Chen X. Intellectual Property Protection of New Animal Breeds in China: Theoretical Justification, International Comparison, and Institutional Construction. Animals. 2025; 15(16):2411. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15162411

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Wenfei, and Xinyi Chen. 2025. "Intellectual Property Protection of New Animal Breeds in China: Theoretical Justification, International Comparison, and Institutional Construction" Animals 15, no. 16: 2411. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15162411

APA StyleZhang, W., & Chen, X. (2025). Intellectual Property Protection of New Animal Breeds in China: Theoretical Justification, International Comparison, and Institutional Construction. Animals, 15(16), 2411. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15162411