Killing Neck Snares Are Inhumane and Non-Selective, and Should Be Banned

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

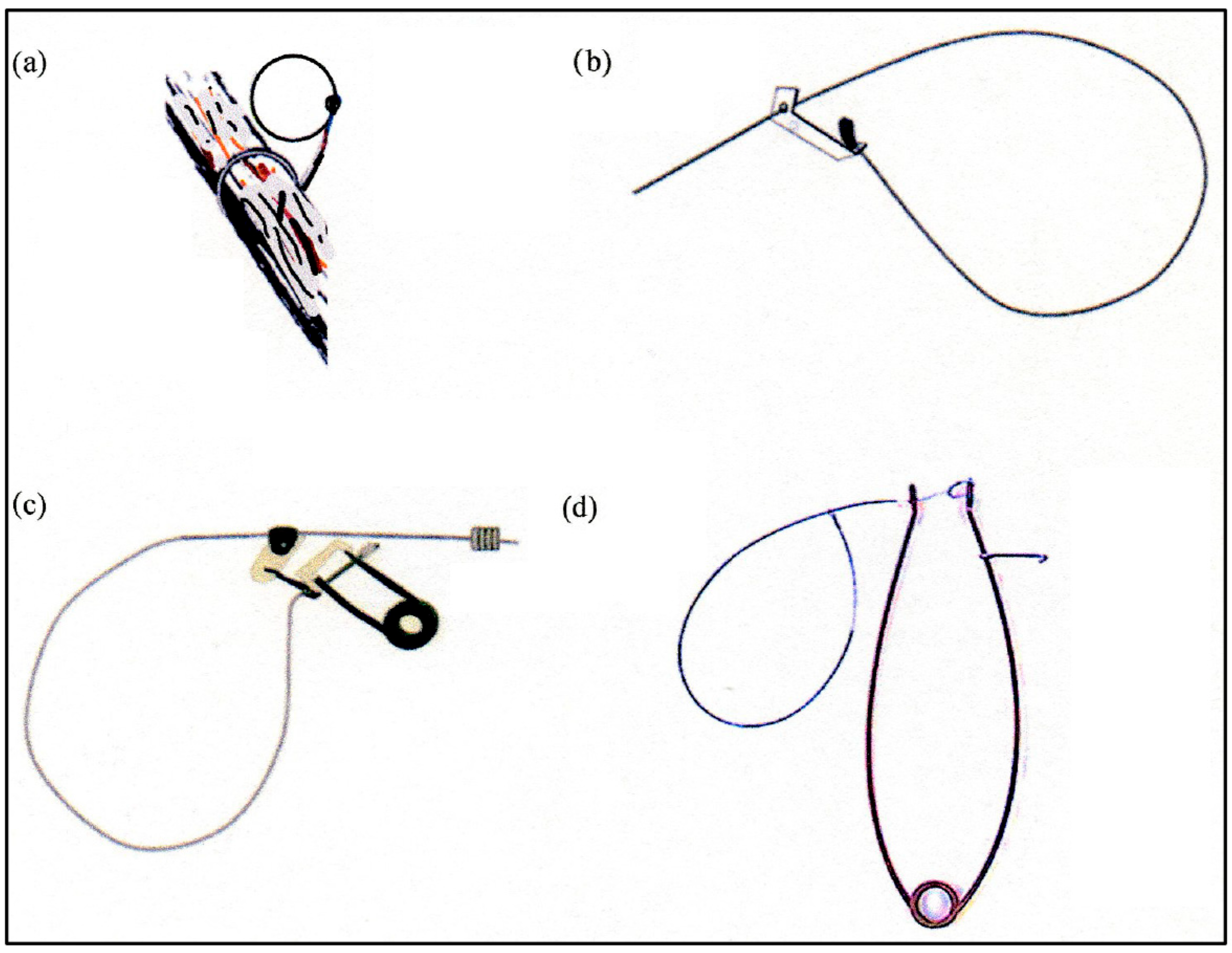

2. Description of Killing Neck Snares

3. Scientific Evidence

3.1. Animal Welfare Standards for Humaneness

3.2. Non-Selectivity

| Snare Type | Species | Methods and Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Braided wire manual snare | Coyotes (Canis latrans) in the wild. | Snares were set along a 27 km route within a 15.5 km2 area. They were checked daily except during rainy weather. The trapping effort was 20,436 snare-days, where a snare-day was one snare operative for 24 h. Of 65 coyotes snared in this study, 59% were neck catches, 20% flanks, 11% front leg and neck, and 10% foot. Of the catch, 52% were dead in the morning after being snared, and 48% were alive. The authors concluded that snares are less humane than other predator control tools. | [18] |

| Braided wire manual snare | Anesthetized red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in laboratory conditions, and one free-ranging fox in a compound. | The study used snare wire diameters and techniques recommended by experienced snare trappers. Experimentation was conducted using anesthetized animals and snares with locks. The objective was to determine the time to death of red foxes snared in the neck region. Researchers applied force to tighten the noose to its smallest diameter, but animals were still breathing 30–40 min after snaring. The length of time elapsing before loss of consciousness and brain death was excessive in most tests. Necropsy findings showed that 8 of 18 foxes exhibited varying degrees of pulmonary edema. A free-ranging fox captured in a snare set in a compound fought the snare deliberately and consistently, and was subjected to euthanasia after five minutes. Researchers believed that the fox could have remained in the snare alive for an extended period of time. Researchers concluded that manual snares could not offer a potentially humane death for canids. | [14] |

| Brass wire manual snare | Red squirrels (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) in laboratory and in simulated environment. | Controlled field tests required that snared red squirrels lose consciousness within 3 min. Two squirrels in simulated environments died or were euthanized 4 min after being captured. In subsequent tests in simulated environments, three red squirrels were still conscious after 3 min and were euthanized. Researchers concluded that snaring does not offer a suitable means of trapping red squirrels humanely. | [14] |

| 3 types of power snares with braided wire | Red foxes in semi-natural environments. | The study was conducted in a 2.2 ha forested compound. Tests included three types of power snares, powered by one or two torsion springs to tighten the noose around an animal’s neck. Cable sizes were 1.2 or 1.6 mm in diameter. Tests required that captured animals lose consciousness within 5 min. Between 50% and 100% of the animals did not lose consciousness within 5 min, and most of them were euthanized. Researchers concluded that power snares developed to quickly kill large furbearers appear to have limited application in the search for humane trapping methods. | [28] |

| Stainless steel wire manual snare | Snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus in semi-natural environments | The study was conducted in a 2.2 ha forested compound. All snowshoe hares were allowed a minimum of 3 days to acclimate to the simulated natural environment before any tests were conducted. A 0.02 gauge stainless steel wire was used. Tests with nine animals showed that the sum of exerting escape attempts lasted, on average, 2.5 min (SE = 0.4). On average, the time to confirmed death was 18 min (SE = 4.4) after capture of the animals. | [29] |

| 3 types of manual snares with braided galvanized aircraft cable | Coyotes in the wild. | In winter predator control programs in Montana, out of 374 captures, 301 (89%) coyotes were snared by the neck. Nearly 50% of the animals were still alive or had escaped the morning after being snared. More than 20% were still alive in one snare type. | [30] |

| Manual snare with braided wire | Canids. | Injuries caused by killing neck snares are described and compared to those caused by steel-jawed leghold traps. Canids are not always captured by the neck, and they suffer severe injuries similar to those observed in animals captured in steel-jawed leghold traps. Abdominal captures may even lead to disembowelment. Neck-captured animals, which do not die rapidly, develop extreme swelling of the neck, head, and eyes, which may freeze shut in winter. | [31] |

| Manual snare with braided wire | 1 coyote and 1 gray wolf (Canis lupus) on a trapline in the wild. | This study occurred on a trapline in the backcountry of Alberta. A trapper had set several snares made of 0.24 cm in diameter, 2.5 m long, aircraft galvanized steel cables. Snares were fastened to rebar anchors, and they were all equipped with one-way Cam-Locks. Snare loops were 30 cm in diameter, and they were set about 30 cm from the ground, more than 10 m from a bait station, which consisted of body parts of deer (Odoileus spp.) and other animals. I set and camouflaged six cameras, at least 1.5 m above the ground and at least 4 m away from snares. Cameras were programmed for 20 to 30 s-long videos, with a 20 s delay between motion-triggered recordings. I returned to the trapping site a few days later, after a few centimeters of snow had fallen. Snares had captured 1 coyote and 1 gray wolf. I reviewed the recordings and noted capture time and irreversible loss of consciousness based on the loss of corneal reflex. During daylight, the blinking of the eyelids indicated that the animals were alive. During nighttime, interruption of the eyeshine (reflection of the camera light from the tapetum lucidum of the eyes) due to the blinking of the eyelids confirmed that the animals were still conscious. The coyote lost consciousness 14 h 16 min after being captured. The wolf lost consciousness 3 h 39 min after being captured. During nearly 50% of their respective capture periods, both animals constantly struggled and showed signs of distress. On the basis of the approximation to the binomial distribution, where 9/9 animals must lose consciousness within 5 min (time limit in the AIHTS), these findings showed that killing neck snares could not humanely kill ≥ 70% of captured canids. | [13] |

| Unspecified | 37 wolves, a protected species in Poland. | Review of 37 wolves snared in Poland between 2014 and 2020, and monitoring of 16 wolves with radio collars and camera traps. Researchers reported evidence of old and severe injuries caused by previous snaring, as well as recordings from camera traps revealing that some wolves escaped from snares and live severely disabled and alone, or supported by their pack mates. | [20] |

| Target Species | Non-Target Captures | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Coyote (Canis latrans) | Bobcats (Lynx rufus); American badger (Taxidea taxus); northern raccoon (Procyon lotor); striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis); gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus); peccary (Pecari tajacu); cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus); black-tailed jackrabbit (Lepus californicus); and armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus); gopher tortoise (Gopherus berlandieri); and domestic animals. | [18] |

| Snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus) | American marten (Martes americana). | [32,33] |

| Gray wolf (Canis lupus) | Moose (Alces americanus), Sitka black-tailed deer (Odoileus hemionus sitkensis), and woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus). | [34] |

| Gray wolf (Canis lupus) | Mountain lion (Puma concolor). | [22,23] |

| Red fox (Vulpes vulpes) | Stone martens (Martes foina), mongoose (Herpestes ichneumon), wild boar (Sus srcofa), and dogs (Canis familiaris). | [27] |

| Coyote, gray wolf, and red fox | Specimens submitted to the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative from 1990–2014: American black bear (Ursus americanus); bobcat (Lynx rufus); Canada lynx (Lynx canadensis); fisher (Pekania pennanti); mountain lion (Puma concolor); snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus); white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus); wolverine (Gulo gulo); bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus); barred owl (Strix varia); common raven (Corvus corax); golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos); goshawk (Accipiter gentilis); great horned owl (Bubo virginianus); red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis); rough-legged hawk (Buteo lagopus). | [5] |

| Red fox and rabbit | In 2017–2021, of 505 snaring non-target captures attended by the RSPCA: 72 European badgers (Meles meles); 17 unspecified deer; 5 gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis); 3 brown hares (Lepus europaeus); 3 hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus); 3 muntjacs (Muntiacus reevesi); 123 cats (Felis catus), 21 dogs (Canis familiaris), 2 horses (Equus ferus caballus), 2 sheep (Ovis aries), 1 cow (Bos taurus); 1 blackbird (Turdus merula), 1 buzzard (Buteo buteo); 1 coot (Fulica spp.); 10 feral pigeons (Columba livia domestica), 7 mute swans (Cygnus olor), 3 Canada geese (Branta canadensis), 3 grey herons (Ardea cinerea), 1 chicken (Gallus gallus), 1 greylag goose (Anser anser), 1 kestrel (Falco spp.), 1 magpie (Pica pica), 1 pheasant (Phasianus spp.), 1 wood pigeon (Columba palumbus), and 1 domestic duck (Anas platyrhynchos). | [26] |

3.3. History Repeating Itself

3.4. Myths and Misinformation

3.5. Poor International Trapping Standards

4. Discussion

- Shouldn’t killing neck snares be subject to the same criteria that are applied to other trapping devices used for the capture of large furbearers, namely canids?

- Given the fact that killing neck snares simply are inhumane restraining trapping devices, shouldn’t they be replaced with restraining devices that have been found to be humane?

- In the past, when the fur market was slow to drive innovation in trap technology, the threat of a trade embargo by the European Community led to the ban on steel-jawed leghold traps and the development of humane trapping standards [15]. Should a similar embargo from fur-buying countries be necessary to ban the use of neck snares?

- Previously, Stevens and Proulx demonstrated how proactive, persistent communication of scientific evidence to decision-makers, wildlife agencies, and the public led to the banning of an inhumane trapping device for northern raccoons (Procyon lotor) [60]. Should wildlife professionals and environmental organizations now launch national and international campaigns to raise awareness and pressure governments to ban killing neck snares?

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Proulx, G. The five Ws of mammal trapping. In Mammal Trapping—Wildlife Management, Animal Welfare & International Standards; Proulx, G., Ed.; Alpha Wildlife Publications: Sherwood Park, AB, Canada, 2022; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Proulx, G.; Barrett, M.W. Animal welfare concerns and wildlife trapping: Ethics, standards and commitments. Trans. West. Sect. Wildl. Soc. 1989, 25, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Proulx, G.; Cattet, M.; Serfass, T.L.; Baker, S.E. Updating the AIHTS trapping standards to improve animal welfare and capture efficiency and selectivity. Animals 2020, 10, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldstein, P.; Proulx, G. Inadequate implementation of AIHTS mammal trapping standards in Canada. In Mammal Trapping—Wildlife Management, Animal Welfare & International Standards; Proulx, G., Ed.; Alpha Wildlife Publications: Sherwood Park, AB, Canada, 2022; pp. 129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Proulx, G.; Rodtka, D.; Barrett, M.W.; Cattet, M.; Dekker, D.; Moffatt, E.; Powell, R.A. Humaneness and selectivity of killing neck snares used to capture canids in Canada: A review. Can. Wildl. Biol. Manag. 2015, 4, 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Boddicker, M.L. Snares for predator control. In Proceedings of the 10th Vertebrate Pest Conference, Monterey, CA, USA, 23–25 February 1982; pp. 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Sinnema, J. A Country Built on Fur. Edmonton Journal, 1 March: B1, B3–B5. 2014. Available online: https://edmontonjournal.com/life/trapper-gordy-klassen-practises-his-own-brand-of-activism-building-awareness-about-canadas-oldest-economic-endeavour (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Martin, E. The Scourge of Snares—Fighting to Eliminate These Cruel Killers of Wildlife. Humane World for Animals. 2018. Available online: https://hsi.org.au/blog/the-scourge-of-snaresfighting-to-eliminate-these-cruel-killers-of-wildlife/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Exposed Wildlife Conservancy. The Case Against Neck Snares. 2024. Available online: https://www.exposedwildlifeconservancy.org/chapter/4-neck-snares (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Judd, E. Blog: It’s Time to End the Cruel Practice of Snaring. League Against Cruel Sports, UK. 2024. Available online: https://www.league.org.uk/news-and-resources/news/Time-to-Ban-Cruel-Snares/#:~:text=The%20indiscriminate%20nature%20of%20snares,cruel%2C%20indiscriminate%2C%20and%20unnecessary (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- OneKind. Snares: The Cruelty. 2025. Available online: https://www.onekind.org/snares-the-cruelty (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- The Fur-Bearers. Killing Neck Snares: Simple Design, Significant Suffering. Available online: https://thefurbearers.com/blog/killing-neck-snares-simple-design-significant-suffering/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Proulx, G. Intolerable Cruelty—The Truth Behind Killing Neck Snares and Strychnine; Alpha Wildlife Publications: Sherwood Park, AB, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- FPCHT (Federal Provincial Committee for Humane Trapping). Report of the Federal Provincial Committee for Humane Trapping. In Proceedings of the Federal-Provincial Wildlife Conference, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 10–13 July 1973. [Google Scholar]

- ECGCGRF (European Community, Government of Canada, and Government of the Russian Federation). Agreement on international humane trapping standards. Off. J. Eur. Communities 1997, 42, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Proulx, G.; Cattet, M.R.L.; Powell, R.A. Humane and efficient capture and handling methods for carnivores. In Carnivore Ecology and Conservation: A Handbook of Techniques; Boitani, L., Powell, R.A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2012; pp. 70–129. [Google Scholar]

- Proulx, G.; Allen, B.L.; Cattet, M.; Feldstein, P.; Iossa, G.; Meek, P.D.; Serfass, T.L.; Soulsbury, C.D. International mammal trapping standards—Part I: Prerequisites. In Mammal Trapping—Wildlife Management, Animal Welfare & International Standards; Proulx, G., Ed.; Alpha Wildlife Publications: Sherwood Park, AB, Canada, 2022; pp. 259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Guthery, F.S.; Beasom, S.L. Effectiveness and selectivity of neck snares in predator control. J. Wildl. Manag. 1978, 42, 457–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoust, P.-Y.; Nicholson, P.H. Severe chronic injury caused by a snare in a coyote. Can. Field-Nat. 2004, 118, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, S.; Żmihorski, M.; Figura, M.; Stachyra, P.; Mysłajek, R.W. The illegal shooting and snaring of legally protected wolves in Poland. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 264, 109367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proulx, G. How does non-selective trapping affect species at risk in Canada? In Wildlife Conservation & Management in the 21st Century—Issues, Solutions and New Concepts; Proulx, G., Ed.; Alpha Wildlife Publications: Sherwood Park, AB, Canada, 2024; pp. 133–158. [Google Scholar]

- Knopff, K.H.; Knopff, A.A.; Boyce, M.S. Scavenging makes cougars susceptible to snaring at wolf bait stations. J. Wildl. Manag. 2010, 74, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proulx, G.; Parr, S.; Elbroch, L.M. Snare-free traplines to protect mountain lions inhabiting Banff and Jasper National Parks, Alberta, Canada. Can. Wildl. Biol. Manag. 2024, 13, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen, A.M.; Stewart, K.M.; Sedinger, J.S.; Lackey, C.W.; Beckmann, J.P. Survival of cougars caught in non-target foothold traps and snares. J. Wildl. Manag. 2018, 82, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villeneuve, K.A.; Proulx, G. Impact of wild mammal trapping on dogs and cats: A search into an unmindful and undisclosed world. In Mammal Trapping—Wildlife Management, Animal Welfare & International Standards; Proulx, G., Ed.; Alpha Wildlife Publications: Sherwood Park, AB, Canada, 2022; pp. 141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, S. A Review of the Use of Snares in the UK. Report Submitted to the National Anti Snaring Campaign. 2022. Available online: https://www.animalaid.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Snaring-report-final-version.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Duarte, J.; Farfán, M.A.; Fa, J.E.; Vargas, J.M. How effective and selective is traditional red fox snaring? Galemys 2012, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Proulx, G.; Barrett, M.W. Assessment of power snares to effectively kill red fox. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 1990, 18, 27–30. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Proulx, G.; Kolenosky, A.J.; Badry, M.J.; Cole, P.J.; Drescher, R.K. A snowshoe hare snare system to minimize capture of marten. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 1994, 22, 639–643. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Phillips, R.L. Evaluation of 3 types of snares for capturing coyotes. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 1996, 24, 107–110. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Proulx, G.; Rodtka, D. Steel-jawed leghold traps and killing neck snares: Similar injuries command a change to agreement on international humane trapping standards. J. Appl. Ani. Welf. Sci. 2017, 20, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, R. Simulated spatial dynamics of martens in response to habitat succession in the western Newfoundland Model Forest. In Martes: Taxonomy, Ecology, Techniques, and Management; Proulx, G., Bryant, H.N., Woodard, P.M., Eds.; Provincial Museum of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 1997; pp. 419–436. [Google Scholar]

- Hearn, B.J. Factors Affecting Habitat Selection and Population Characteristics of American Marten (Martes americana atrata) in Newfoundland. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Maine, Orono, ME, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, C.L. Reducing non-target moose capture in wolf snares. Alces 2010, 46, 167–182. [Google Scholar]

- World Organization for Animal Health. Terrestrial Animal Health Code. 2018. Available online: https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahc/2018/en_sommaire.htm (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Canadian Council on Animal Care Guidelines: Wildlife. 2023. Available online: https://ccac.ca/Documents/Standards/Guidelines/CCAC_Guidelines-Wildlife.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Rowsell, H.C. Research for development of comprehensive humane trapping systems snare study, Part I. In University of Ottawa Report Submitted to the Federal Provincial Committee for Humane Trapping; University of Ottawa: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Andeweg, J. The anatomy of collateral venous flow from the brain and its value in aetiological interpretation of intracranial pathology. Neuroradiology 1996, 38, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyramid Productions Inc. Unnatural Enemies: The War on Wolves; Pyramid Productions Inc.: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fur Institute of Canada. Best Trapping Practices for Killing Neck Snares. 2024. Available online: https://fur.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/coyote-kill-snare-best-design-February-2024.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. Modern Snares for Capturing Mammals: Definitions, Mechanical Attributes and Use Considerations. 2009. Available online: https://www.fishwildlife.org/application/files/5515/2002/6134/Modern_Snares_final.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Swan, M. Humane Fox Snares and International Standards. Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust. 2022. Available online: https://www.gwct.org.uk/blogs/news/2022/january/humane-fox-snares-and-international-standards/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Issel-Tamer, L.; Rine, J. The evolution of mammalian olfactory receptor genes. Genetics 1997, 145, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, S.; Sjőberg, J.; Amundin, M.; Hartmann, C.; Buettner, A.; Laska, M. Behavioral responses to mammalian blood odor and a blood odor component in four species of large carnivores. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberta Trappers’ Association. Snares. 2022. Available online: https://www.albertatrappers.com/position-statements/snares (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Tullar, B.F. Evaluation of a padded leghold trap for trapping foxes and raccoons. N. Y. Fish Game J. 1984, 31, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, G.H.; Linhart, S.B.; Dasch, G.J.; Male, C.B. Injuries to coyotes caught in padded and unpadded steel foothold traps. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 1986, 14, 219–223. [Google Scholar]

- Proulx, G.; Rodtka, D. Killing traps and snares in North America: The need for stricter checking time periods. Animals 2019, 9, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proulx, G. Modifications to improve the performance of mammal trapping systems. In Mammal Trapping—Wildlife Management, Animal Welfare & International Standards; Proulx, G., Ed.; Alpha Wildlife Publications: Sherwood Park, AB, Canada, 2022; pp. 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, C.A.; Allen, L.; Gigliotti, F.; Busana, F.; Gonzalez, T.; Lindeman, M.; Fisher, P.M. Evaluation of the trap tranquiliser device (TTD) for improving the humaneness of dingo trapping. Anim. Welf. 2004, 13, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahr, D.P.; Knowlton, F.F. Evaluation of tranquilizer trap devices (ITDs) for foothold traps used to capture gray wolves. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2000, 28, 597–605. [Google Scholar]

- Savarie, P.J.; Vice, D.S.; Bangerter, L.; Dustin, K.; Paul, W.J.; Primus, T.M.; Blom, F. Operational Field Evaluation of a Plastic Bulb Reservoir as a Tranquiliser Trap Device for Delivering Propiopromazine Hydrochloride to Feral Dogs, Coyotes, and Gray Wolves; USDA National Wildlife Research Center—Staff Publications: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2004; p. 383. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, R.A.; Proulx, G. Trapping and marking terrestrial mammals for research: Integrating ethics, standards, techniques, and common sense. ILAR 2003, 44, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iossa, G.; Soulsbury, C.D.; Harris, S. Mammal trapping: A review of animal welfare standards of killing and restraining traps. Anim. Welf. 2007, 16, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogelsinger, A. International trapping: The need for international trapping standards. Anim. Nat. Resour. Law 2017, 13, 67. Available online: https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/janimlaw13&div=7&id=&page= (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Zuardo, T. How the United States was able to dodge international reforms designed to make wildlife trapping less cruel. J. Intern. Wildl. Law Policy 2017, 20, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louchouarn, N.X.; Proulx, G.; Serfass, T.L.; Niemeyer, C.C.; Treves, A. Best management practices for furbearer trapping derived from poor and misleading science. Can. Wildl. Biol. Manag. 2024, 13, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Canac-Marquis, P. Canadian Wild Fur Production from 2010 to 2019; Fur Institute of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fur Institute of Canada. Trap Types. 2025. Available online: https://fur.ca/fur-trapping/trap-types/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Stevens, E.; Proulx, G. Empowering the public to be critical consumers of mammal trapping (mis) information: The case of the northern raccoon captured in a Conibear 220 trap in a Kansas suburb. In Mammal Trapping—Wildlife Management, Animal Welfare & International Standards; Proulx, G., Ed.; Alpha Wildlife Publications: Sherwood Park, AB, Canada, 2022; pp. 153–160. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Proulx, G. Killing Neck Snares Are Inhumane and Non-Selective, and Should Be Banned. Animals 2025, 15, 2220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15152220

Proulx G. Killing Neck Snares Are Inhumane and Non-Selective, and Should Be Banned. Animals. 2025; 15(15):2220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15152220

Chicago/Turabian StyleProulx, Gilbert. 2025. "Killing Neck Snares Are Inhumane and Non-Selective, and Should Be Banned" Animals 15, no. 15: 2220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15152220

APA StyleProulx, G. (2025). Killing Neck Snares Are Inhumane and Non-Selective, and Should Be Banned. Animals, 15(15), 2220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15152220