A Brown Bear’s Days in Vilnius, the Capital of Lithuania

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Urban and Peri-Urban Bears in the World

1.2. Brown-Bear–Human Conflict in Europe and the Use of Urban Territories

1.3. Brown Bear in Lithuania

2. Materials and Methods

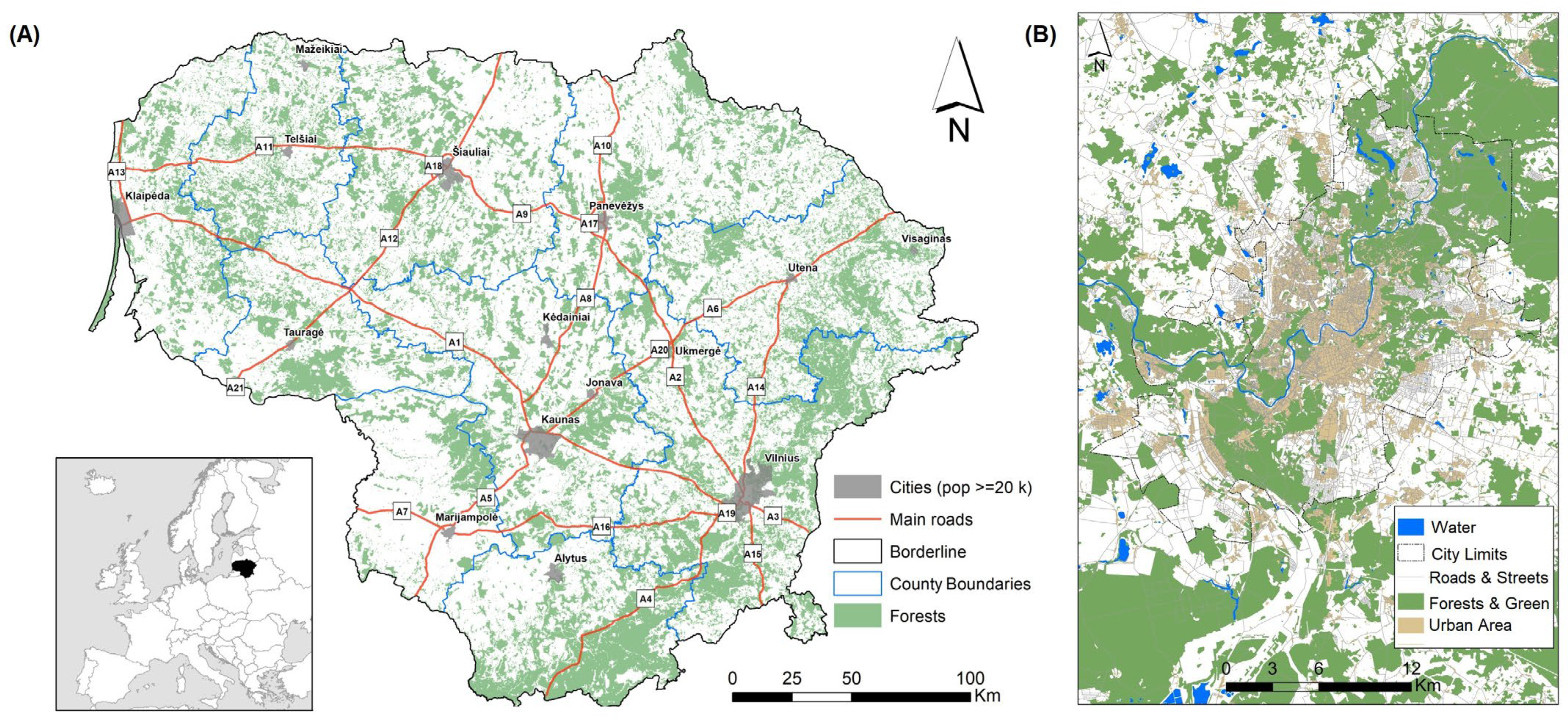

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Information Sources

3. Results

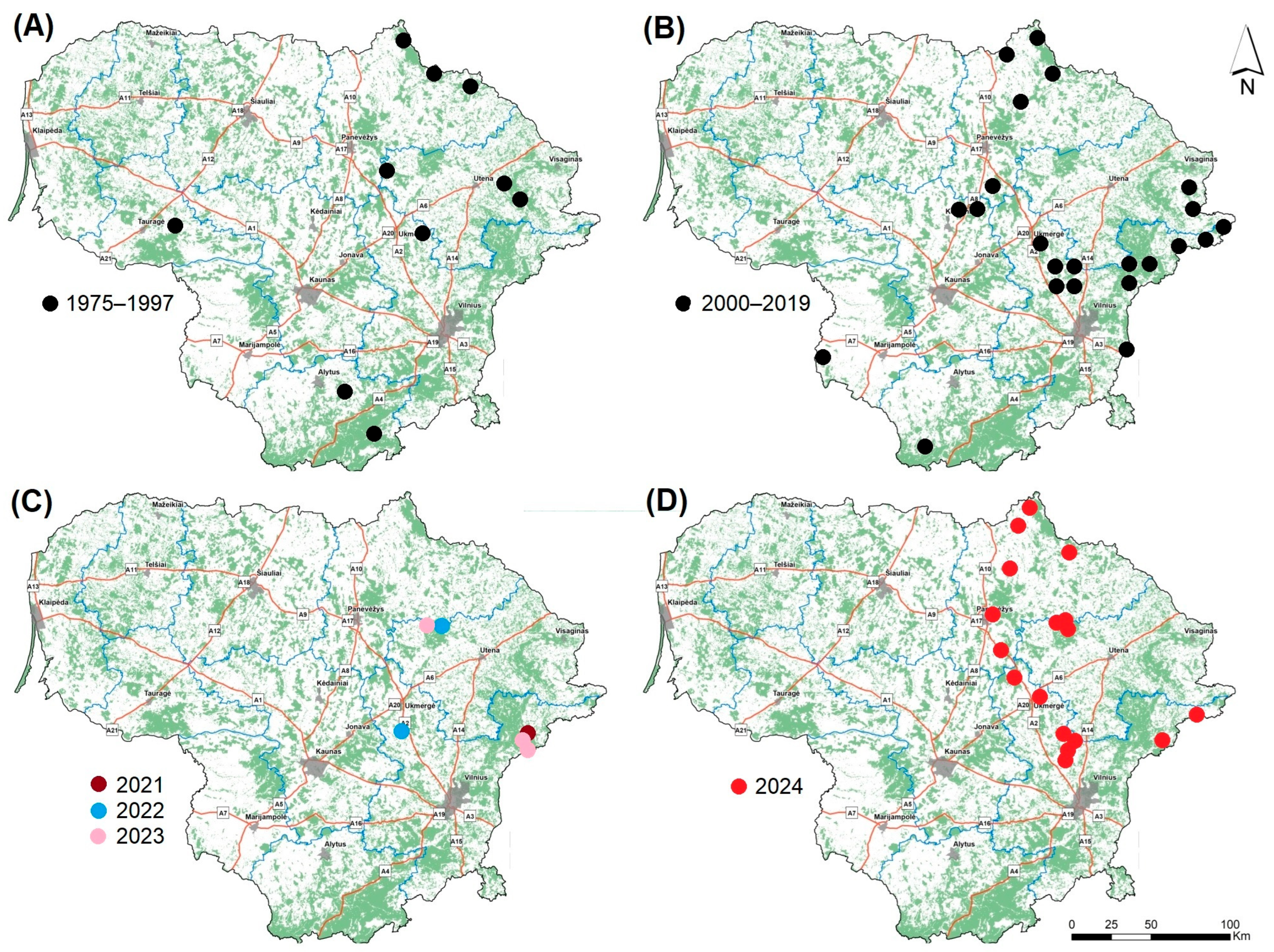

3.1. Brown Bear Population Recovery in Lithuania

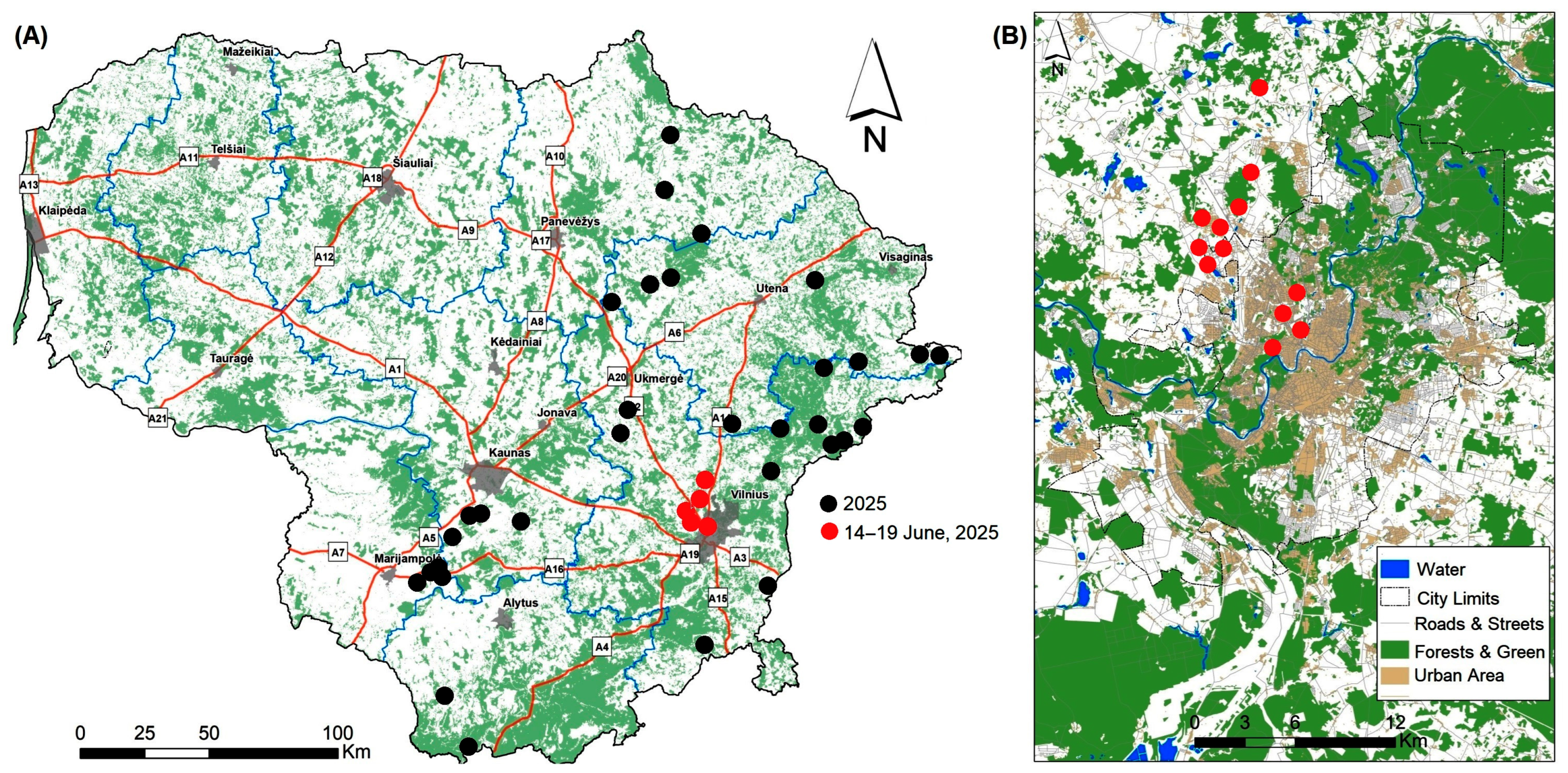

3.2. Brown Bear Visit to the Capital City of Lithuania

3.3. Institutional Response

- June 15 (AM, LMŽD). The AM presented “invasive plans”—first, they would attempt to sedate the animal, tag it with a GPS device, and release it back to the forest; only in a critical case, they would shoot the bear. It was emphasized that lethal measures would only be taken in threatening situations. Hunters may be issued permits, but this would require communication mechanisms at the state level [47].

- June 16 (AM, VS). Residents were urged to avoid outdoor activities, keep their children indoors, and steer clear of forests. They were also reminded to call 112, the emergency number, if a bear was spotted. Gaps in communication were confirmed and were planned to be addressed [48].

- June 16 (AAD, LMŽD). It was reported that the bear had left Vilnius. Drones were used to monitor the animal’s movements, which emphasized vigilance and readiness to track its further movements. [49].

- June 17 (AM, AAD, VS, VrS, LGGC). The deputy minister acknowledged shortcomings in communication and promised to address them by creating action plans for bear-related incidents. They presented a plan that included GPS tracking, sedation, and, in critical cases, shooting. Clear protocols were to be developed. Municipal representatives complained about the lack of information [50].

- June 17 (LMŽD). The LMŽD and the hunters obtained permission and decided not to shoot the bear, but rather to observe and tag it. They criticized the authorities for suggesting shooting instead of tagging. They emphasized the need for a long-term wildlife management system [51].

- June 17 (AM, AAD). The deputy minister acknowledged the public’s lack of information regarding the animal’s whereabouts and institutional actions. The challenges of drone surveillance were discussed, as were plans to improve the communication and coordination of operations [52].

- June 18 (AM, Committee on Environment Protection). The deputy minister explained that shooting was only one of the options considered, and that it would be used only in extreme cases. He emphasized that the primary goal was to allow the bear to return to the wild on its own and that hunters would only intervene as a last resort. Therefore, there were no direct orders to shoot [53].

- June 18 (AM, Speaker of the Seimas S. Skvernelis). Seimas Speaker S. Skvernelis offered a critical assessment of the situation, calling it “tragicomic” and expressing dissatisfaction with how the institutions handled the situation and communicated [54].

- June 18 (Seimas members, Committee on Environment Protection). Members of the Seimas were outraged that the authorities intended to shoot the bear too quickly without first taking adequate measures to observe and tag it. There was criticism regarding the inadequate response and lack of transparency [55].

- June 18 (AM, President of the Republic of Lithuania). The President asked why the authorities did not take clear action, such as tracking, tranquilizing, and tagging the bear, instead of shooting it. His criticism highlights the authorities’ shortcomings in planning and communication [56].

4. Discussion

4.1. Urban and Peri-Urban Large Carnivores Pose a Dilemma for Their Management

4.2. Lithuanian Brown Bears: Visitors Stay?

4.3. Lithuanian Experiences: The Moose and the Brown Bear Visit to the Capital City

4.4. Foreign Media Framing of the Vilnius Bear Incident

4.5. Symbolic Wildlife and the Media: The Bear as Spectacle, Distraction, and Narrative Device

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAD | Environmental Protection Department under the Ministry of Environment (Aplinkos apsaugos departamentas prie Aplinkos ministerijos) |

| AM | Ministry of Environment of the Republic of Lithuania (Lietuvos respublikos Aplinkos ministerija) |

| LMŽD | Lithuanian Hunters and Fishers Association (Lietuvos medžiotojų ir žvejų draugija) |

| LGGC | Wildlife Rescue Centre (Laukinių gyvūnų globos centras) |

| VS | Vilnius municipality (Vilniaus savivaldybė) |

| VrS | Vilnius district municipality (Vilniaus rajono savivaldybė) |

References

- Po Vilnių Toliau Blaškosi Meška—Užfiksuota Judrioje Gatvėje: Būkite Atsargūs [A Bear Continues to Roam Vilnius—Spotted on a Busy Street: Please Be Careful]. Available online: https://www.tv3.lt/naujiena/lietuva/po-vilniu-toliau-blaskosi-meska-uzfiksuota-judrioje-gatveje-bukite-atsargus-n1428580 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Po Dramatiškų Savaitgalio Įvykių Kritikos Strėlės Ministerijai: Daugiau tai Pasikartoti Negali [After Dramatic Weekend Events, Criticism Directed at Ministry: This Cannot Happen Again]. Available online: https://www.delfi.lt/news/daily/lithuania/po-dramatisku-savaitgalio-ivykiu-kritikos-streles-ministerijai-daugiau-tai-pasikartoti-negali-120118626 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Rašomavičius, V. (Ed.) Brown bear. In Red Data Book of Lithuania. Animals, Plants, Fungi; Ministry of Environment of the Republic of Lithuania: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2021; p. 303. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, P.W.; Fleming, P.A. Big city life: Carnivores in urban environments. J. Zool. 2012, 287, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, J.P.; Lackey, C.W. Carnivores, urban landscapes, and longitudinal studies: A case history of black bears. Hum.-Wildl. Confl. 2008, 2, 168–174. [Google Scholar]

- Pasitschniak-Arts, M. Ursus arctos. Mamm. Species 1993, 439, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, C.T.; Smit, L.; Mowat, G.; McLellan, B.; Proctor, M. Unsecured attractants, collisions, and high mortality strain coexistence between grizzly bears and people in the Elk Valley, southeast British Columbia. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2023, 5, e13012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohorović, M.; Krofel, M.; Jerina, K. Pregled prilagajanja rabe prostora rjavega medveda (Ursus arctos) na antropogene motnje [Review of brown bear (Ursus arctos) spatial use adaptation to anthropogenic disturbances]. Acta Silvae Ligni 2017, 113, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simberloff, D. Biodiversity and bears: A conservation paradigm shift. Ursus 1999, 11, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Jarić, I.; Normande, I.C.; Arbieu, U.; Courchamp, F.; Crowley, S.L.; Jeschke, J.M.; Roll, U.; Sherren, K.; Thomas-Walters, L.; Veríssimo, D.; et al. Flagship individuals in biodiversity conservation. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2024, 22, e2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, L. What Good Is a Bear to Society? Soc. Anim. 2014, 22, 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, M.; Steins, N.A.; van Bets, L. Combining polar cruise tourism and science practices. Ann. Tour. Res. 2024, 107, 103794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouros, G. Wildlife—Watching Tourism of Romania and Its Impact on Species and Habitats. Int. J. Responsible Tour. 2012, 1, 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Penteriani, V.; López-Bao, V.J.; Bettega, C.; Dalerum, F.; Delgado, M.M.; Jerina, K.; Kojola, I.; Krofel, M.; Ordiz, A. Consequences of brown bear viewing tourism: A review. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 206, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, M.L.; Service, C.N.; Suraci, J.P.; Artelle, K.A.; Field, K.A.; Darimont, C.T. Ecology of fear alters behavior of grizzly bears exposed to bear-viewing ecotourism. Ecology 2024, 105, e4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penteriani, V.; Delgado, M.M.; Pinchera, F.; Naves, J.; Fernández-Gil, A.; Kojola, I.; Härkönen, S.; Norberg, N.; Frank, J.; Fedriani, M.J.; et al. Human behaviour can trigger large carnivore attacks in developed countries. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nettles, J.M.; Brownlee, M.T.; Jachowski, D.S.; Sharp, R.L.; Hallo, J.C. American residents’ knowledge of brown bear safety and appropriate human behavior. Ursus 2021, 32e18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toncheva, S.; Fletcher, R. From conflict to conviviality? Transforming human–bear relations in Bulgaria. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 2, 682835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimpoca, A.; Voiculescu, M. Patterns of Human–Brown Bear Conflict in the Urban Area of Brașov, Romania. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madadi, M.; Nezami, B.; Kaboli, M.; Rezaei, H.R.; Mohammadi, A. Human–brown bear conflicts in the North of Iran: Implication for conflict management. Ursus 2023, 34e2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balseiro, A.; Herrero-García, G.; García Marín, J.F.; Balsera, R.; Monasterio, J.M.; Cubero, D.; Royo, L.J. New threats in the recovery of large carnivores inhabiting human-modified landscapes: The case of the Cantabrian brown bear (Ursus arctos). Vet. Res. 2024, 55, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bombieri, G.; Penteriani, V.; Delgado, M.D.M.; Groff, C.; Pedrotti, L.; Jerina, K. Towards understanding bold behaviour of large carnivores: The case of brown bears in human-modified landscapes. Anim. Conserv. 2021, 24, 783–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuțoiu, A.G.; Ionescu, O. Economic Analysis of Human and Brown Bear Conflicts. Rev. Silvic. Cineget. 2023, 28, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Can, Ö.E.; D’Cruze, N.; Garshelis, D.L.; Beecham, J.; Macdonald, D.W. Resolving human–bear conflict: A global survey of countries, experts, and key factors. Conserv. Lett. 2014, 7, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krofel, M.; Elfström, M.; Ambarlı, H.; Bombieri, G.; González-Bernardo, E.; Jerina, K.; Laguna, A.; Penteriani, V.; Phillips, J.P.; Selva, N. Human–Bear Conflicts at the Beginning of the Twenty-First Century: Patterns, Determinants, and Mitigation Measures. In Bears of the World. Ecology, Conservation and Management; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; Volume 15, pp. 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garshelis, D.L.; Baruch-Mordo, S.; Bryant, A.; Gunther, K.A.; Jerina, K. Is Diversionary Feeding an Effective Tool for Reducing Human–Bear Conflicts? Case Studies from North America and Europe. Ursus 2017, 28, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, K.; Solić, A.; Huber, D.; Röttger, C.; Froese, I.; Schmidt, J. Large Carnivores in the Dinarides: Management, Monitoring, Threats and Conflicts: Establishing a Transnational Exchange Platform for the Management of Large Carnivores in the Dinaric Region: Background Report. Available online: https://bfn.bsz-bw.de/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/1044/file/Skript617.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Karamanlidis, A.A.; Sanopoulos, A.; Georgiadis, L.; Zedrosser, A. Structural and Economic Aspects of Human–Bear Conflicts in Greece. Ursus 2011, 22, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, M.I.; Iosif, R.; Promberger-Fürpass, B.; Chiriac, S.; Keresztesi, Á.; Rozylowicz, L.; Popescu, V.D. Romanian Brown Bear Management Regresses. Science 2025, 387, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, M.; Zedrosser, A.; Kojola, I.; Swenson, J.E. The Management of Brown Bears in Sweden, Norway and Finland. In Bear and Human: Facets of a Multi-Layered Relationship from Past to Recent Times, with Emphasis on Northern Europe; Brepols Publishers: Turnhout, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://www.brepolsonline.net/doi/epdf/10.1484/M.TANE-EB.5.134326?role=tab (accessed on 18 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Prūsaitė, J. (Ed.) Fauna of Lithuania. In Mammals; Mokslas: Vilnius, Lithuania, 1988; pp. 183–185. [Google Scholar]

- Micelicaitė, V.; Piličiauskienė, G.; Podėnas, V.; Minkevičius, K.; Damušytė, A. Zooarchaeology of the Late Bronze Age Fortified Settlements in Lithuania. Heritage 2023, 6, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietuvoje Pastebėtų Meškų Žemėlapis [Map of Bears Spotted in Lithuania]. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/viewer?ll=55.295491223183774%2C25.60712869999999&z=7&mid=1BeBqmrGoDHFyJc7AO_sH5K1diLDlWn0 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Skelbia, Kad Lietuva Gali Džiaugtis dar Viena Gyvūnų Rūšimi: Užfiksuotas Meškos Jauniklis [Lithuania Has Something to Rejoice About: A Bear Cub Has Been Spotted]. Available online: https://www.lrytas.lt/gamta/fauna/2025/04/02/news/skelbia-kad-lietuva-gali-dziaugtis-dar-viena-gyvunu-rusimi-uzfiksuotas-meskos-jauniklis-37179793 (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- EU. Available online: https://european-union.europa.eu/principles-countries-history/eu-countries/lithuania_en (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- European Environmental Agency CORINE Land Cover—Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/pan-european/corine-land-cover (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Saugomų Teritorijų Valstybės Kadastras. Available online: https://stvk.lt/map (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Vilnius. Available online: https://www.vle.lt/straipsnis/vilnius-1/ (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Balčiauskas, L.; Trakimas, G.; Juškaitis, R.; Ulevičius, A.; Balčiauskienė, L. Lietuvos Žinduolių, Varliagyvių ir Roplių Atlasas. Atlas of Lithuanian Mammals, Amphibians and Reptiles, 2nd ed.; Akstis: Vilnius, Lithuania, 1999; p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- Baranauskas, K.; Balčiauskas, L.; Mažeikytė, R. Vilnius City Theriofauna. Acta Zool. Litu. 2005, 15, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamačius, Kas Atklydo iš Miško Prienų Rajone, Negalėjo Patikėti Savo Akimis: Parodė Visiems [When They Saw What Had Come out of the Forest in the Prienai District, They Couldn’t Believe Their Eyes and Showed It to Everyone]. Available online: https://www.tv3.lt/naujiena/gyvenimas/pamacius-kas-atklydo-is-misko-prienu-rajone-negalejo-patiketi-savo-akimis-parode-visiems-n1425740 (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Miškuose 20 km nuo Kauno Pastebėtas Rudasis Lokys [A Brown Bear Was Spotted in the Woods 20 km from Kaunas]. Available online: https://www.delfi.lt/grynas/gamta/miskuose-20-km-nuo-kauno-pastebetas-rudasis-lokys-120115263 (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Medžiotojai Praneša: Rudasis Lokys Užfiksuotas Netoli Kauno [Hunters Report: Brown Bear Spotted Near Kaunas]. Available online: https://www.15min.lt/naujiena/aktualu/lietuva/medziotojai-pranesa-rudasis-lokys-uzfiksuotas-netoli-kauno-56-2463496 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Paaiškėjo, Kur Dabar Yra Meškutė, per Timberlake`o Koncertą Keliavusi Link Kauno [The Whereabouts of the Bear Cub That Traveled to Kaunas During Timberlake’s Concert Have Been Revealed]. Available online: https://www.tv3.lt/naujiena/gyvenimas/paaiskejo-kur-dabar-yra-meskute-per-timberlake-o-koncerta-keliavusi-link-kauno-n1428280 (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Pasitikrinkite, ar Meška Praėjo Pro Jūsų Namus: Parodė, Kur Lankėsi [Determine If a Bear Has Passed by Your House by Checking Where It Has Been]. Available online: https://www.tv3.lt/naujiena/gyvenimas/pasitikrinkite-ar-meska-praejo-pro-jusu-namus-parode-kur-lankesi-n1429188?priority=6 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Lankėsi ir Jūsų Gatvėje? Meškos Maršrutas Vilniuje—Pagal Žmonių Skambučius Tarnyboms [Did It Visit Your Street? Here Is the Bear’s Route in Vilnius, Based on Calls to Emergency Services]. Available online: https://www.15min.lt/naujiena/aktualu/lietuva/lankesi-ir-jusu-gatveje-meskos-marsrutas-vilniuje-pagal-zmoniu-skambucius-tarnyboms-56-2471170 (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Dėl Meškos Vilniuje Teks Griebtis Naujo Plano: Neišvengiamas ir Liūdnasis Scenarijus [A New Plan Will Have to Be Devised for the Bear in Vilnius: A Sad Scenario Is Also Inevitable]. Available online: https://www.delfi.lt/news/daily/lithuania/del-meskos-vilniuje-teks-griebtis-naujo-plano-neisvengiamas-ir-liudnasis-scenarijus-120118610 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Dėl Meškos—Skubūs Pranešimai Gyventojams: Nepalikite Vaikų Lauke, Nesilankykite Miške [An Urgent Message for Residents Regarding Bear: Do Not Leave Children Outside, and Do Not Enter the Forest]. Available online: https://www.tv3.lt/naujiena/lietuva/del-meskos-skubus-pranesimai-gyventojams-nepalikite-vaiku-lauke-nesilankykite-miske-n1428926 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Oficialu: Meškos Vilniuje Nebėra [It’s Official—There Are No More Bears in Vilnius]. Available online: https://www.delfi.lt/news/daily/lithuania/oficialu-meskos-vilniuje-nebera-120118715 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Spaudos Konferencija dėl Vilniaus Apylinkėse Klaidžiojančios Meškos [Press Conference on a Bear Wandering Around Vilnius]. Available online: https://www.delfi.lt/news/daily/lithuania/spaudos-konferencija-del-vilniaus-apylinkese-klaidziojancios-meskos-120118548 (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Medžiotojai Atsisakė Nušauti po Vilnių Klaidžiojusią Mešką: Paaiškėjo, Kas Vyks Toliau [Hunters Refused to Shoot a Bear Wandering Around Vilnius: It Became Clear What Will Happen Next]. Available online: https://www.tv3.lt/naujiena/lietuva/medziotojai-atsisake-nusauti-po-vilniu-klaidziojusia-meska-paaiskejo-kas-vyks-toliau-n1429144?priority=16 (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Į Vilnių Atklydus Meškai, Tarnybos Pripažįsta: Trūko Komunikacijos Iš Mūsų Pusės [After a Bear Wandered into Vilnius, Authorities Admit: There Was a Lack of Communication on Our Part]. Available online: https://www.bernardinai.lt/i-vilniu-atklydus-meskai-tarnybos-pripazista-truko-komunikacijos-is-musu-puses/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Kilus Diskusijoms—Aplinkos Viceministro Atkirtis: Aplinkos Viceministras: “Jokio Pavedimo Medžioti Lokį Nebuvo” [When Discussions Arose, the Deputy Minister of the Environment Responded: Deputy Minister of the Environment: “There Was No Order to Hunt the Bear”]. Available online: https://www.tv3.lt/naujiena/lietuva/kilus-diskusijoms-aplinkos-viceministro-atkirtis-aplinkos-viceministras-jokio-pavedimo-medzioti-loki-nebuvo-n1429449 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Po Meškos Vizito Sostinėje—S. Skvernelio Kirčiai Aplinkos Ministerijai: “Tikrai Tragikomiška” [After the Bear’s Visit to the Capital, S. Skvernelis Criticizes the Ministry of the Environment: “Truly Tragicomic”]. Available online: https://www.lrytas.lt/gamta/fauna/2025/06/18/news/po-meskos-vizito-sostineje-s-skvernelio-kirciai-aplinkos-ministerijai-tikrai-tragikomiska--38319117 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Seime Liejasi Įtūžis Dėl Vilniuje Pasirodžiusios Meškos: Kas gi Jums Atsitiko, Kurgi Jūs Šašlykavot [There Is Outrage in the Seimas over the Appearance of a Bear in Vilnius: What Happened to You, Where Did You Go for a Barbecue?]. Available online: https://www.delfi.lt/news/daily/lithuania/seime-liejasi-ituzis-del-vilniuje-pasirodziusios-meskos-kas-gi-jums-atsitiko-kurgi-jus-saslykavot-120119156 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Pamatęs, Kaip po Vilnių Blaškėsi Meška, Nausėda Kirto: “Kodėl tai Nebuvo Padaryta?” [Seeing How the Bear Roamed Around Vilnius, Nausėda Snapped, “Why Wasn’t This Done?”]. Available online: https://www.tv3.lt/naujiena/lietuva/pamates-kaip-po-vilniu-blaskesi-meska-nauseda-kirto-kodel-tai-nebuvo-padaryta-n1429613?priority=13 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Sato, Y. The Future of Urban Brown Bear Management in Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan: A Review. Mammal Study 2017, 42, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A.L.; Ryan, D.A.J. A Tale of Two Cities, with Bears: Understanding Attitudes towards Urban Bears in British Columbia, Canada. Urban Ecosyst. 2019, 22, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bears Stray into Political Territory in Romania and Slovakia. Available online: https://balkaninsight.com/2025/04/21/bears-stray-into-political-territory-in-romania-and-slovakia/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Polish Mayor Demands Brown Bear Cullings as Human Encounters Surge. Available online: https://tvpworld.com/86160964/-polish-mayor-demands-brown-bear-cullings-as-human-encounters-surge (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Nellemann, C.; Støen, O.-G.; Kindberg, J.; Swenson, J.E.; Vistnes, I.; Ericsson, G.; Katajisto, J.; Kaltenborn, B.P.; Martin, J.; Ordiz, A. Terrain Use by an Expanding Brown Bear Population in Relation to Age, Recreational Resorts and Human Settlements. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 138, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertel, A.G.; Parres, A.; Frank, S.C.; Renaud, J.; Selva, N.; Zedrosser, A.; Balkenhol, N.; Maiorano, L.; Fedorca, A.; Dutta, T.; et al. Human Footprint and Forest Disturbance Reduce Space Use of Brown Bears (Ursus arctos) across Europe. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moen, G.K.; Ordiz, A.; Kindberg, J.; Swenson, J.E.; Sundell, J.; Støen, O.G. Behavioral Reactions of Brown Bears to Approaching Humans in Fennoscandia. Écoscience 2019, 26, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Bernardo, E.; Delgado, M.d.M.; Matos, D.G.G.; Zarzo-Arias, A.; Morales-González, A.; Ruiz-Villar, H.; Skuban, M.; Maiorano, L.; Ciucci, P.; Balbontín, J.; et al. The Influence of Road Networks on Brown Bear Spatial Distribution and Habitat Suitability in a Human-Modified Landscape. J. Zool. 2023, 319, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traukinys Kupiškio Rajone Numušė Rudąjį Lokį [A Train Hit a Brown Bear in the Kupiškis District]. Available online: https://www.lrt.lt/naujienos/lietuvoje/2/2312894/traukinys-kupiskio-rajone-numuse-rudaji-loki (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Biržų Rajone Aptikti Meškos Pėdsakai [Bear Tracks Found in Biržai District]. Available online: https://www.15min.lt/naujiena/gyvunu-klubas/ivykiai/birzu-rajone-aptiktos-meskos-pedos-172-228703 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Į Biržų Girią Užklydusią Mešką Miškininkas Lepina Medumi [A Forester Treats a Bear That Wandered into the Biržai Forest with Honey]. Available online: https://www.alfa.lt/straipsnis/50390588/i-birzu-giria-uzklydusia-meska-miskininkas-lepina-medumi/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Pasienyje su Baltarusija Baigtas Statyti Fizinis Barjeras [A Physical Barrier Has Been Completed on the Border with Belarus]. Available online: https://www.lrt.lt/naujienos/lietuvoje/2/1768287/pasienyje-su-baltarusija-baigtas-statyti-fizi-nis-barjeras? (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Vis Dažnesnės Viešnios: Meška per Čepkelių Raistą Atkeliavo iš Baltarusijos [Increasingly Frequent Visitors: A Bear Arrived from Belarus Via the Čepkeliai Marshes]. Available online: https://www.15min.lt/naujiena/aktualu/lietuva/vis-daznesnes-viesnios-meska-per-cepkeliu-raista-atkeliavo-is-baltarusijos-56-2458882 (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Į Lietuvą iš Baltarusijos Naktį Atplaukė Meška [A Bear Swam from Belarus to Lithuania at Night]. Available online: https://www.lrytas.lt/gamta/fauna/2025/06/05/news/i-lietuva-is-baltarusijos-nakti-atplauke-meska-38152838 (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Kasdien Tikrai Nepamatysi: Pasienyje Pasirodė Retas Mūsų Krašte Gyvūnas [You Won’t See This Every Day: A Rare Animal Has Appeared in Our Region.]. Available online: https://www.delfi.lt/tv/mokslas-ir-gamta/kasdien-tikrai-nepamatysi-pasienyje-pasirode-retas-musu-kraste-gyvunas-93365499 (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Pamatykite—Meška Pasienyje Bandė Perlipti Spygliuotą Tvorą [Look—A Bear Tried to Climb over the Barbed Wire Fence on the Border]. Available online: https://www.tv3.lt/naujiena/video/pamatykite-meska-pasienyje-bande-perlipti-spygliuota-tvora-n1256203 (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Atsakė, Koks Likimas Laukia į Vilnių Atklydusio Briedžio ir Kokią Klaidą Darė Gyventojai [Answered What Fate Awaited the Moose That Had Wandered into Vilnius, and What Mistake the Residents Had Made]. Available online: https://www.delfi.lt/kartu/zmones-kalba/atsake-koks-likimas-laukia-i-vilniu-atklydusio-briedzio-ir-kokia-klaida-dare-gyventojai-120111267 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Briedžio Blaškymasis po Vilnių Baigėsi: Žvėris iš Upės Išlipo į Krantą, Juo Rūpinasi Specialistai [The Moose’s Travels Around Vilnius Have Come to a Close: The Animal Has Climbed out of the River and Is Now Being Attended to by Experts]. Available online: https://zmones.15min.lt/naujiena/briedzio-gelbejimo-operacija-vilniuje-zveris-islipo-i-kranta-juo-rupinasi-specialistai-645gNypkVoZ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Gamtininkas Apie Briedžio Patirtą Stresą Vilniuje: Įsivaizduokite Save Tarp 3 Tūkst. Liūtų [Naturalist on the Stress Experienced by an Elk in Vilnius: Imagine Yourself Among 3000 Lions]. Available online: https://www.lrt.lt/naujienos/lietuvoje/2/2569487/gamtininkas-apie-briedzio-patirta-stresa-vilniuje-isivaizduokite-save-tarp-3-tukst-liutu (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Apklausa: Ar Jaučiatės Saugiai Vilniaus Gatvėse, Kai Jomis Bėgioja Meška? [Survey: Do You Feel Safe on the Streets of Vilnius When There Bear is Running Around?]. Available online: https://madeinvilnius.lt/savaites-klausimas/apklausa-ar-jauciates-saugiai-vilniaus-gatvese-kai-jomis-begioja-meska/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Meška iš Vilniaus Dingo, o Problemos Tik Prasidėjo: Kai Kam Tai Kainuos Labai Skaudžiai [The Bear from Vilnius Is Gone, but the Problems Have Only Just Begun: For Some, It Will Be Very Costly]. Available online: https://www.lrytas.lt/bustas/pasidaryk-pats/2025/06/18/news/meska-is-vilniaus-dingo-o-problemos-tik-prasidejo-kai-kam-tai-kainuos-labai-skaudziai-38319038 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Aplinkos Viceministras Atsakė, ką Veikė, kol Vilniečius Šiurpino Meška: “Šašlykavom, Kaip ir Visi Normalūs Žmonės” [The Deputy Minister of the Environment Responded to What He Was Doing While Vilnius Residents Were Being Terrorized by a Bear: “We Were Barbecuing, Like All Normal People.”]. Available online: https://www.tv3.lt/naujiena/lietuva/aplinkos-viceministras-atsake-ka-veike-kol-vilniecius-siurpino-meska-saslykavom-kaip-ir-visi-normalus-zmones-n1429629 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Meškos Klajonės Vilniuje Parodė Tikrąjį Vaizdą: Kas Turi Prisiimti Atsakomybę? [The Bear’s Wanderings in Vilnius Showed the Real Picture: Who Should Take Responsibility?]. Available online: https://www.delfi.lt/news/daily/lithuania/meskos-klajones-vilniuje-parode-tikraji-vaizda-kas-turi-prisiimti-atsakomybe-120119632 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Meškos Gastrolės Vilniuje Įkvėpė Įmones: Pasipylė Šmaikščios Reklamos [The Bear’s Tour in Vilnius Inspired Companies: Witty Advertisements Appeared]. Available online: https://www.15min.lt/verslas/naujiena/bendroves/meskos-gastroles-vilniuje-ikvepe-imones-socialiniuose-tinkluose-pasipyle-smaikscios-reklamos-663-2472604 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Vilniaus Meška Užfiksuota Smaguriaujanti Netoli Kito Lietuvos Miesto. Available online: https://www.lrytas.lt/gamta/fauna/2025/06/18/news/meska-is-vilniaus-uzfiksuota-smaguriaujanti-netoli-kito-lietuvos-miesto-38318461 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Bergman, J.N.; Buxton, R.T.; Lin, H.-Y.; Lenda, M.; Attinello, K.; Hajdasz, A.C.; Rivest, S.A.; Nguyen, T.T.; Cooke, S.J.; Bennett, J.R. Evaluating the Benefits and Risks of Social Media for Wildlife Conservation. Facets 2022, 7, 360–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.J.; Burton, A.C. Social Media Community Groups Support Proactive Mitigation of Human–Carnivore Conflict in the Wildland–Urban Interface. Trees For. People 2022, 10, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Lee, A.T.; Luo, Y.; Alexander, J.S.; Shi, X.; Sangpo, T.; Clark, S.G. Large Carnivore Encounters through the Lens of Mobile Videos on Social Media. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2023, 5, e12907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lithuania Hunters Refuse to Kill Bear That Ambled Around Vilnius for Two Days. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/jun/19/lithuania-hunters-refuse-to-kill-bear-that-ambled-around-vilnius-for-two-days (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- A Wild Bear Enters Lithuania’s Capital. Hunters Refuse a Government Request to Shoot the Animal. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/lithuania-bear-vilnius-protected-species-2e6fd88748f386cd250c2f50a4587ad9 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- In Lithuania, a Brown Bear Roamed the Capital’s Streets for Two Days—Hunters Did Not Follow the Government’s Order to Kill the Animal. Available online: https://unn.ua/en/news/in-lithuania-a-brown-bear-roamed-the-capitals-streets-for-two-days-hunters-did-not-follow-the-governments-order-to-kill-the-animal (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Lithuania’s Capital to Use Drones for Animal Tracking After Wild Bear Sighting. Available online: https://tvpworld.com/87312403/lithuanias-capital-to-use-drones-for-animal-tracking-after-wild-bear-sighting (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Buller, H. Where the Wild Things Are: The Evolving Iconography of Rural Fauna. J. Rural Stud. 2004, 20, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, T.M.; Schüttler, E.; Benavides, P.; Gálvez, N.; Saborido, M.; Saavedra, B.; Ortega, R. Values, Animal Symbolism, and Human–Animal Relationships Associated to Two Threatened Felids in Mapuche and Chilean Local Narratives. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, J.G.; Ksiazek, T.B. The Dynamics of Audience Fragmentation: Public Attention in an Age of Digital Media. J. Commun. 2012, 62, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darimont, C.T.; Hall, H.; Eckert, L.; Mihalik, I.; Artelle, K.; Treves, A.; Paquet, P.C. Large Carnivore Hunting and the Social License to Hunt. Conserv. Biol. 2021, 35, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovardas, T. (Ed.) Addressing Human Dimensions in Large Carnivore Conservation and Management: Insights from Environmental Social Science and Social Psychology. In Large Carnivore Conservation and Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtimäki, M. Natural Environments in Narrative Contexts: Cross-Pollinating Ecocriticism and Narrative Theory. Storyworlds 2013, 5, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInturff, A.; Volski, L.; Callahan, M.M.; Sneegas, G.; Pellow, D.N. Pathways between people, wildlife and environmental justice in cities. People Nat. 2025, 7, 575–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name (Abbreviation) | Functions |

|---|---|

| Ministry of Environment (AM) | Develops national conservation policy and international agreements. |

| Environmental Protection Department (AAD) | Subordinate to AM; enforces environmental laws, issues permits, and conducts inspections. |

| Vilnius municipality (VS) | Implements environmental issues, including the maintenance of biodiversity and green spaces, as well as community outreach at the city level |

| Vilnius district municipality (VrS) | Implements environmental issues and community outreach at district level. |

| Lithuanian Hunters and Fishers Association (LMŽD) | Represents hunting and fishing interests; conducts field operations such as roadkill cleanup. |

| Wildlife Rescue Center (LGGC) | A subsidiary of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences; cares for, rehabilitates, and transports injured or distressed wild animals. Located about 115 km from the center of Vilnius. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balčiauskas, L.; Balčiauskienė, L. A Brown Bear’s Days in Vilnius, the Capital of Lithuania. Animals 2025, 15, 2151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15142151

Balčiauskas L, Balčiauskienė L. A Brown Bear’s Days in Vilnius, the Capital of Lithuania. Animals. 2025; 15(14):2151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15142151

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalčiauskas, Linas, and Laima Balčiauskienė. 2025. "A Brown Bear’s Days in Vilnius, the Capital of Lithuania" Animals 15, no. 14: 2151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15142151

APA StyleBalčiauskas, L., & Balčiauskienė, L. (2025). A Brown Bear’s Days in Vilnius, the Capital of Lithuania. Animals, 15(14), 2151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15142151