How Changing Portraits and Opinions of “Pit Bulls” Undermined Breed-Specific Legislation in the United States

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Rise of Pit Bull Positivity

2. Theoretical Background and Expectations

3. Methods and Materials

4. Results and Analysis

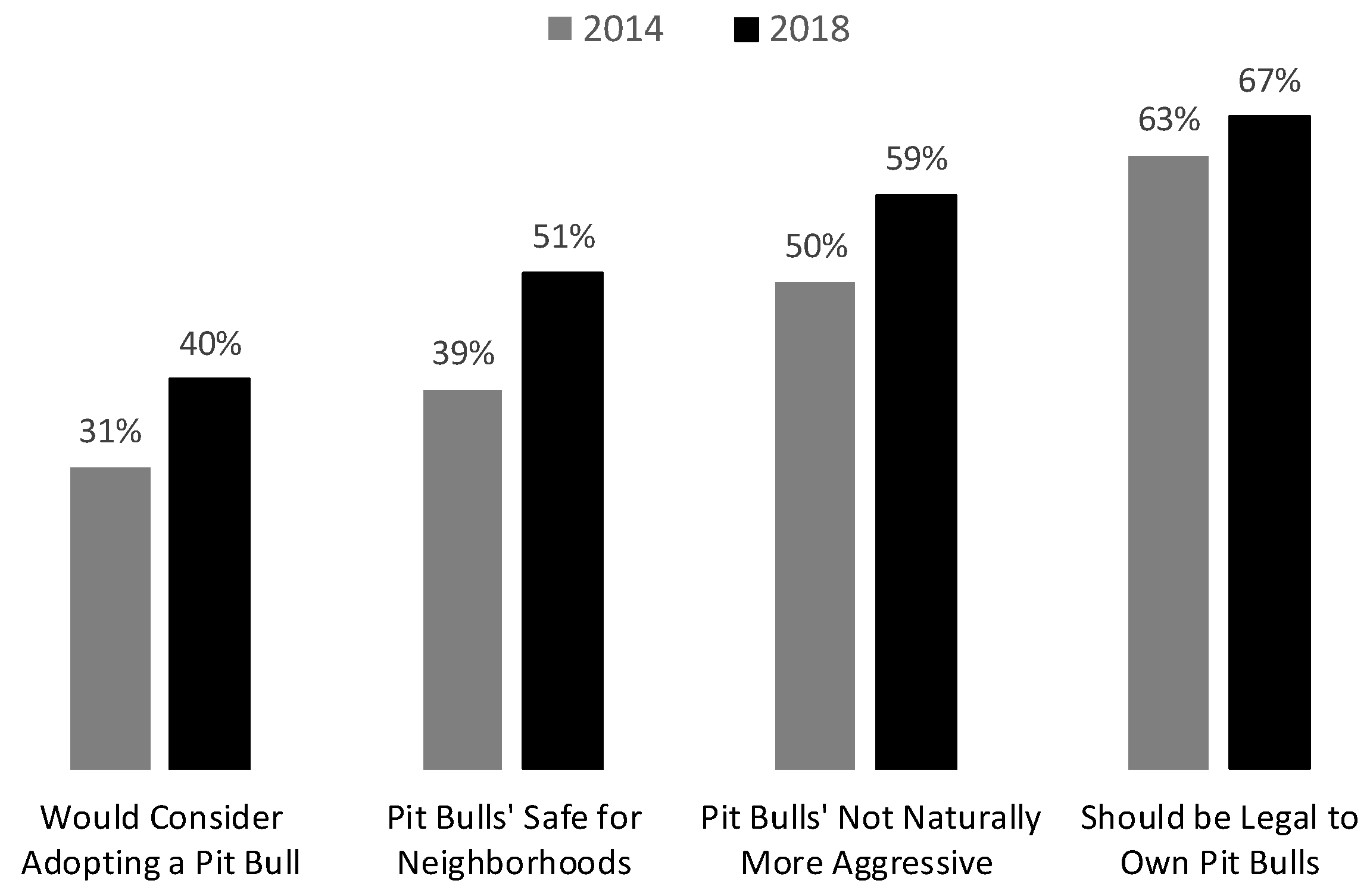

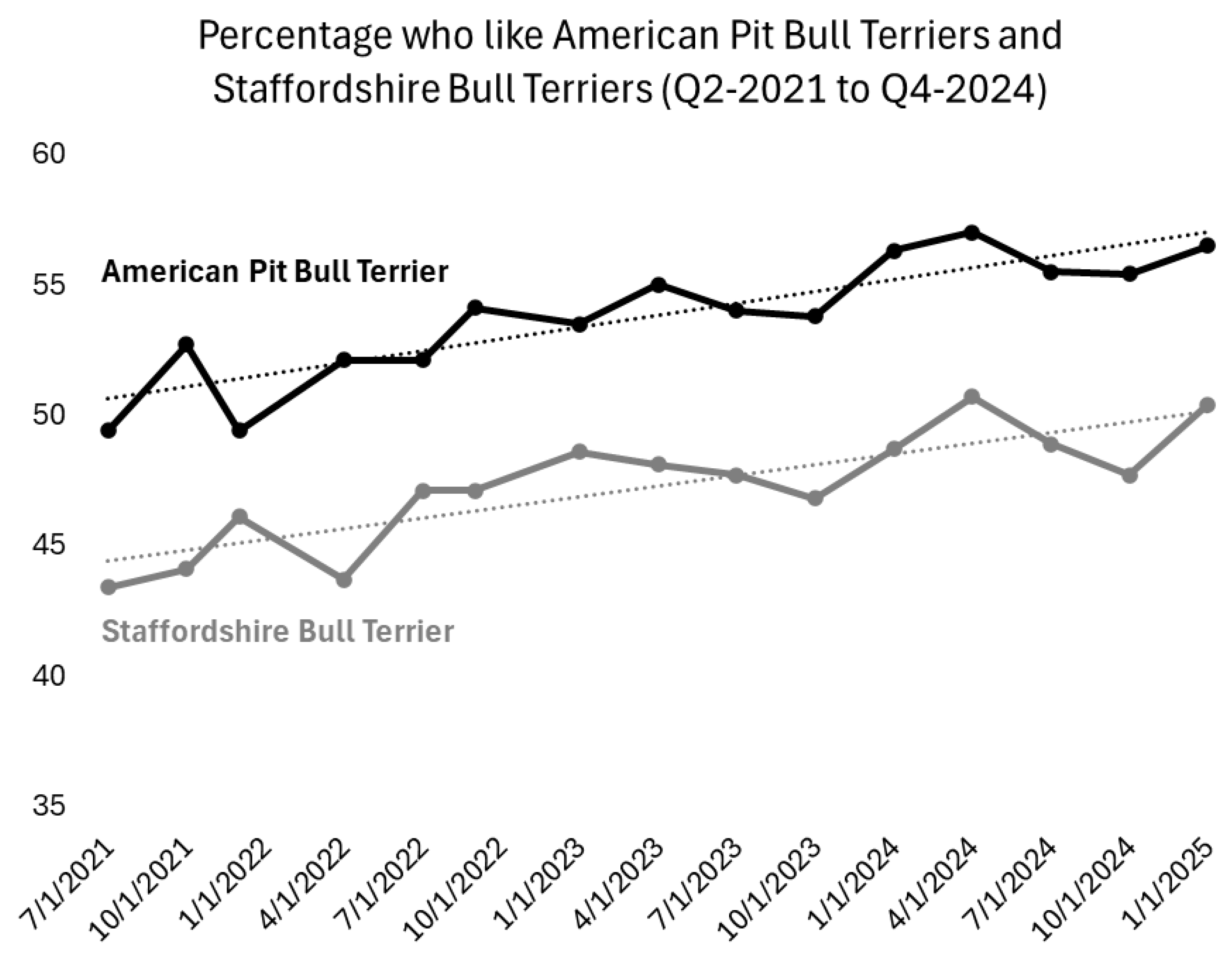

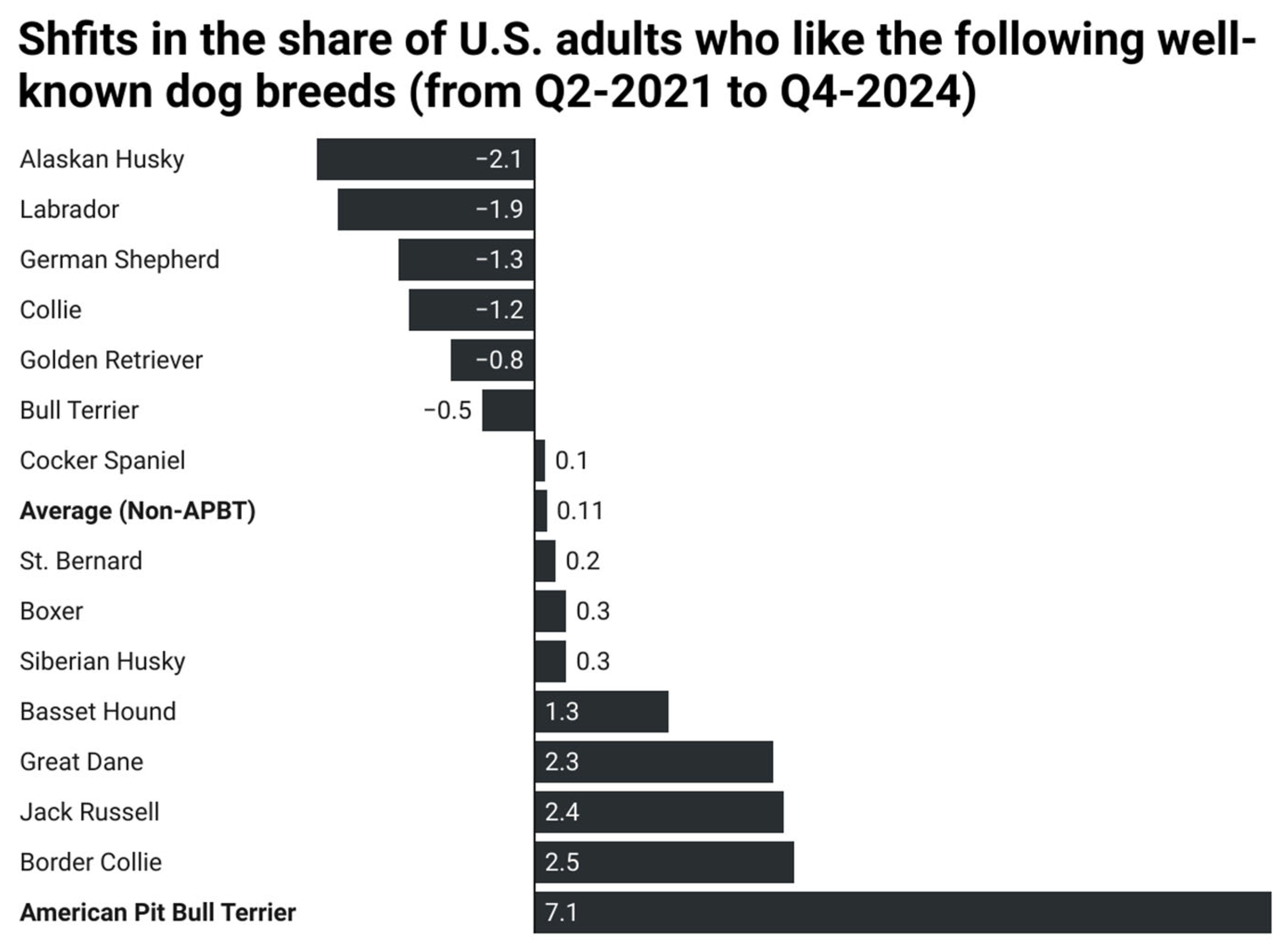

4.1. Shifts in Public Opinion, 2014–2024

4.2. Repealing Local BSL

4.3. Policy Narratives and State Laws Prohibiting Breed-Specific Discrimination

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Collier, S. Breed-specific legislation and the pit bull terrier: Are the laws justified? J. Vet. Behav. 2006, 1, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, S.A.; Schalke, E.; von Gaertner, A.M.; Hackbarth, H. Is there a difference? Comparison of golden retrievers and dogs affected by breed-specific legislation regarding aggressive behavior. J. Vet. Behav. 2008, 3, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalke, E.; Ott, S.A.; von Gaertner, A.M.; Hackbarth, H.; Mittmann, A. Is breed-specific legislation justified? Study of the results of the temperament test of Lower Saxony. J. Vet. Behav. 2008, 3, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patronek, G.J.; Sacks, J.J.; Delise, K.M.; Cleary, D.V.; Marder, A.R. Co-occurrence of potentially preventable factors in 256 dog bite–related fatalities in the United States (2000–2009). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2013, 243, 1726–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, R.A.; Bethany, L.; Christine, B.; Gemma, J.R.; Emily, J.B. Human directed aggression in domestic dogs (Canis familiaris): Occurrence in different contexts and risk factors. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 152, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creedon, N.; Páraic, S.Ó.S. Dog bite injuries to humans and the use of breed-specific legislation: A comparison of bites from legislated and non-legislated dog breeds. Ir. Vet. J. 2017, 70, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, A.; Thomas, R.; Daniel, S.M.; Małgorzata, P. Comparison of behavioural tendencies between “dangerous dogs” and other domestic dog breeds–Evolutionary context and practical implications. Evol. Appl. 2022, 15, 1806–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrill, K.; Jessica, H.; Xue, L.; Jesse, M.; Brittney, L.; Linda, G.; Mingshi, G. Ancestry-inclusive dog genomics challenges popular breed stereotypes. Science 2022, 376, eabk0639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Temperament Test Society. ATTS Breed Statistics. 2009. Available online: https://atts.org/breed-statistics/statistics-page1/ (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Tesler, M.; McThomas, M. The racialization of pit bulls: What dogs can teach us about racial politics. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0305959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesler, M. Rafael Warnock’s Dog Ads Cut Against White Voters’ Stereotypes of Black People; FiveThirtyEight: Boston, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, E. Rising from The Pit. American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. 2017. Available online: https://www.aspcapro.org/blog/2017/05/19/rising-pit (accessed on 9 August 2019).

- Gunter, L.M.; Rebecca, T.B.; Clive, D.L.W. What’s in a name? Effect of Breed Perceptions & Labeling on Attractiveness, Adoptions & Length of Stay for Pit-bull-Type Dogs. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146857. [Google Scholar]

- Patronek, G.; Twining, H.; Arluke, A. Managing the stigma of outlaw breeds: A case study of pit bull owners. Soc. Anim. 2000, 8, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delise, K. The Pit Bull Placebo: The Media, Myths and Politics of Canine Aggression; Anubis Publishing: Norwood, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, S. Unleashed: The Phenomenon of Status Dogs and Weapon Dogs; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dickey, B. Pit Bull: The Battle over an American Icon; Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Best, J. Constructing animal species as social problems. Sociol. Compass 2018, 12, e12630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duberstein, A.; Betz, K.; Amy, R.J. Pit bulls and prejudice. Humanist. Psychol. 2023, 51, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Richardson, J. Pit bull panic. J. Pop. Cult. 2002, 36, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalof, L.; Taylor, C. The discourse of dog fighting. Humanit. Soc. 2007, 31, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.J. Dangerous Crossings: Race, Species and Nature in a Multicultural Age; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tarver, E.C. The dangerous individual (’s) dog: Race, criminality and the ‘pit bull’. Cult. Theory Crit. 2014, 55, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, A. The Black Man’s Dog: The social context of breed specific legislation. Anim. L. 2018, 25, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Boisseron, B. Afro-Dog: Blackness and the Animal Question; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, A.J.; Pickett, J.T.; Intravia, J. Racial stereotypes, extended criminalization, and support for Breed-Specific Legislation: Experimental and observational evidence. Race Justice 2022, 12, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, K.M. The Lives and Deaths of Shelter Animals: The Lives and Deaths of Shelter Animals; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hyhan, B. Pet Killed in Dog Fight: A Lesson Learned. Santa Fe New Mexican 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia v. Village of Tijeras, 767 P.2d 355, 359 (N.M. Ct. App. 1988). Available online: https://law.justia.com/cases/new-mexico/court-of-appeals/1988/9424-2.html (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Capp, D. American Pit Bull Terriers: Fact or Fiction? The Truth Behind One of America’s Most Popular Breeds; Doral Publishing, Inc.: Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- McThomas, M.; Michael, T. The Racial Politics of Pit Bulls; Book manuscript in progress; University of California: Irvine, CA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Voith, V.L.; Trevejo, R.; Dowling-Guyer, S.; Chadik, C.; Marder, A.; Johnson, V.; Irizarry, K. Comparison of visual and DNA breed identification of dogs and inter-observer reliability. Am. J. Sociol. Res. 2013, 3, 1729. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, C.L.; Natalie, H.; London, W.; Carri, W. Is that dog a pit bull? A cross-country comparison of perceptions of shelter workers regarding breed identification. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2014, 17, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, K.R.; Levy, J.K.; Norby, B.; Crandall, M.M.; Broadhurst, J.E.; Jacks, S.; Barton, R.C.; Zimmerman, M.S. Inconsistent identification of pit bull-type dogs by shelter staff. Vet. J. 2015, 206, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunter, L.M.; Rebecca, T.B.; Clive, D.L.W. A canine identity crisis: Genetic breed heritage testing of shelter dogs. PloS ONE 2018, 13, e0202633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorant, J. What Happened to Vick’s Dogs…; Sports Illustrated: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Available online: https://www.si.com/more-sports/2008/12/23/vick-dogs (accessed on 9 August 2019).

- Gorant, J. The Lost Dogs: Michael Vick’s Dogs and Their Tale of Rescue and Redemption; Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gorant, J. The Found Dogs: The Fates and Fortunes of Michael Vick’s Pitbulls, 10 Years After Their Heroic Rescue; BookBaby: Pennsauken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ASPCA. Legendary Actor Patrick Stewart Honored with ASPCA Pit Bull Advocate & Protector Award. 2021. Available online: https://www.aspca.org/news/legendary-actor-patrick-stewart-honored-aspca-pit-bull-advocate-protector-award (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Kantor, J. The Pit Bull Influencers Reclaiming the Dogs’ Image One IG Post at a Time; The Ringer: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.theringer.com/pop-culture/2020/8/19/21375963/pit-bull-influencers-gracie-rey-bronson (accessed on 25 August 2020).

- Greenwood, A. Pit Bull Lovers Gather in Washington to Show That Dogs ‘Are Born Inherently Good’; HuffPost: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/pit-bull-washington_n_5260387 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Position Statement on Breed-Specific Legislation. 2019. Available online: https://www.aspca.org/about-us/aspca-policy-and-position-statements/position-statement-breed-specific-legislation (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Breed Specific Legislation—A Dog’s Dinner. 2014. Available online: https://www.rspca.org.uk/webContent/staticImages/Downloads/BSL_Report.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- American Kennel Club. Issue Analysis: Why Breed Specific Legislation Does Not Work. 2017. Available online: https://www.akc.org/expert-advice/news/issue-analysis-breed-specific-legislation/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- American Veterinary Medical Association. 2014. Position Statement on Breed-Specific Legislation. Available online: https://avsab.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Breed-Specific_Legislation-download-_8-18-14.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Australian Veterinary Association. Breed Specific Legislation. 2016. Available online: https://www.ava.com.au/policy-advocacy/policies/companion-animals-dog-behaviour/breed-specific-legislation/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- British Veterinary Association. BVA and BSAVA on the Dangerous Dogs Act (1991) and Dog Control; BSAVA: Gloucester, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.bva.co.uk/media/4115/full-position-bva-and-bsava-position-on-the-dda-and-dog-control.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- American Dog Breeders Association. ADBA Position Statement on Breed Specific Legislation (BSL). 2016. Available online: https://adbadog.com/position-statement-breed-specific-legislation/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Human Society of the United States. Repealing Brees Specific Legislation. 2019. Available online: https://humanepro.org/page/repealing-breed-specific-legislation (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- United Kennel Club. N.D. United Kennel Club Position Statement on Breed Specific Legislation. Available online: https://www.ukcdogs.com/docs/legal/breed-standard-for-bsl.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- American Bar Association. Resolution 100. 2012. Available online: https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/tips/animal-law/res-100.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Association of Professional Dog Trainers. Breed Specific Legislation Position Statement. 2001. Available online: https://apdt.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/PositionStatement.BreedSpecificLegislation_and_FAQs.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- State Farm Insurance. It’s not the Breed—Any Dog Can Bite. 2024. Available online: https://www.statefarm.com/simple-insights/family/its-not-the-breed-its-the-dog-bite (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- National Animal Care and Control Association. NACA Statement on Breed Specific Legislation; NACA: Boston, MA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.nacanet.org/naca-statement-on-breed-specific-legislation/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Best Friends Animal Society. N.D. Ending Restrictions Based on Dog Breed. Available online: https://bestfriends.org/advocacy/ending-breed-specific-legislation (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- National Black Caucus of State Legislators. Policy Resolution CYF-22-23: Restricting Certain Dog Breeds. 2022. Available online: https://nbcsl.org/public-policy/resolution/cyf-22-23/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Sacks, J.J.; Sinclair, L.; Gilchrist, J.; Golab, G.C.; Lockwood, R. Breeds of dogs involved in fatal human attacks in the United States between 1979 and 1998. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2000, 217, 836–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obama White House. Breed Specific Legislation is a Bad Idea. 2013. Available online: https://petitions.obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/petition/ban-and-outlaw-breed-specific-legislation-bsl-united-states-america-federal-level-0/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Browne, G.S. Television and prejudice reduction: When does television as a vicarious experience make a difference? J. Soc. Issues 1999, 55, 707–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, M.; Jake, H. A social cognitive theory approach to the effects of mediated intergroup contact on intergroup attitudes. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2007, 51, 615–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiappa, E.; Gregg, P.B.; Hewes, D.E. Can one TV show make a difference? A Will & Grace and the parasocial contact hypothesis. J. Homosex. 2006, 51, 15–37. [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer, M. The Pit Bull Gets a Rebrand. New York Times, 4 January 2019. Section ST, p. 8. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/04/style/pit-bull-pibble.html (accessed on 6 January 2019).

- Bryant, C. Pit Bull Influencers on a Mission to Change Hearts and Minds; Great Pet Care: Pendle Hill, NSW, Australia, 2023; Available online: https://living.greatpetcare.com/inspiration/pit-bull-influencers-on-a-mission/ (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Bond, B.J. The development and influence of parasocial relationships with television characters: A longitudinal experimental test of prejudice reduction through parasocial contact. Commun. Res. 2021, 48, 573–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, B.J.; Benjamin, L.C. Gay on-screen: The relationship between exposure to gay characters on television and heterosexual audiences. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2015, 59, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonds-Raacke, J.M.; Elizabeth, T.; Cady, M.S.; Rebecca, S.; Richard, J.H.; Lindsey, F. Remembering Gay/Lesbian Media Characters. J. Homosex. 2007, 53, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lienemann, B.A.; Heather, T.S. The association between media exposure of interracial relationships and attitudes toward interracial relationships. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 43, E398–E415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer-Gusé, E.; Katherine, R.D.; Michelle, O. Reducing prejudice through narratives: An examination of the mechanisms of vicarious intergroup contact. J. Media Psychol. 2019, 31, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujioka, Y. Television portrayals and African-American stereotypes: Examination of television effects when direct contact is lacking. J. Mass Commun. Q. 1999, 76, 52–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffner, C.A.; Elizabeth, L.C. Portrayal of mental illness on the TV series Monk: Presumed influence and consequences of exposure. Health Commun. 2012, 30, 1046–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garretson, J.J. Exposure to the lives of lesbians and gays and the origin of young people’s greater support for gay rights. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2015, 27, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrar, S.; Markus, B. Entertainment-education effectively reduces prejudice. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2018, 21, 1053–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, D.A.; Abigail, C.S.; Gaganjyot, S.; Traci, M. Effects of competing news media frames of weight on antifat stigma, beliefs about weight and support for obesity-related public policies. Int. J. Obes. 2015, 40, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasubramanian, S. Using celebrity news stories to effectively reduce racial/ethnic prejudice. J. Soc. Issues 2015, 71, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, N.C.H.; Lookadoo, K.L.; Nisbett, G.S. “I’m Demi and I have bipolar disorder”: Effect of parasocial contact on reducing stigma toward people with bipolar disorder. Commun. Stud. 2017, 68, 314–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eno, C.A.; David, R.E. The influence of explicitly and implicitly measured prejudice on interpretations of and reactions to black film. Media Psychol. 2010, 13, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluck, E.L. Reducing intergroup prejudice and conflict using the media: A field experiment in Rwanda. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilali, R.; Johanna, R.V. Priming effects of a reconciliation radio drama on historical perspective-taking in the aftermath of mass violence in Rwanda. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 49, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, J.; Pratto, F. Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kinder, D. Prejudice and Politics. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology; Huddy, L., David, O.S., Jack, S.L., Jennifer, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 987–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Banaji, M.R.; Greenwald, G.G. Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People; Bantam: Santa Cruz, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Page, B.I.; Shapiro, R.Y. Effects of public opinion on policy. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1983, 77, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, R.S.; Mackuen, M.; Stimson, J.A. The Macro Polity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Soroka, S.N.; Wlezien, C. Degrees of Democracy: Politics, Public Opinion, and Policy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Caughey, D.; Warshaw, C. Dynamic Democracy: Public Opinion, Elections, and Policymaking in the American States; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lax, J.R.; Phillips, J. The democratic deficit in the states. Am. J. Political Sci. 2012, 56, 148–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, J. The thermostatic model of responsiveness in the American states. State Politics Policy Q. 2013, 13, 306–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, D.M.; Nickerson, D. Can learning constituency opinion affect how legislators vote? Results from a field experiment. Q. J. Political Sci. 2011, 6, 55–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, L.R.; Page, B.I. Who influences US foreign policy? Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2005, 99, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, L.M. Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age; Princton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gilens, M. Affluence and Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gilens, M.; Benjamin, I.P. Testing theories of American politics: Elites, interest groups, and average citizens. Perspect. Politics 2014, 12, 564–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstein, P. The impact of public opinion on public policy: A review and an agenda. Political Res. Q. 2003, 56, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlezien, C.; Soroka, S.N. Public opinion and public policy. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, A.; Ingram, H. Social construction of target populations: Implications for politics and policy. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1993, 87, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.L.; Ingram, H.M. Policy Design for Democracy; University of Kansas Press: Lawrence, KS, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, J.J.; Siddiki, S.; Jones, M.D.; Schumacher, K.; Pattison, A.; Peterson, H. Social construction and policy design: A review of past applications. Policy Stud. J. 2014, 42, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boushey, G. Targeted for diffusion? How the use and acceptance of stereotypes shape the diffusion of criminal justice policy innovations in the American states. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2016, 110, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech, B.; Paul, R.K.; Rena, B. Social construction, political power, and the allocation of benefits to endangered species. Conserv. Biol. 1998, 12, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, M.; Jessica, E.S.; Lisa, M.; Louise, M. The social construction of narratives and arguments in animal welfare discourse and debate. Animals 2022, 12, 2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, J.E.; Barbara, W.; Boat, F.W.; Putnam, H.F.D.; Andrew, R.M. Ownership of high-risk (“vicious”) dogs as a marker for deviant behaviors: Implications for risk assessment. J. Interpers. Violence 2006, 21, 1616–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragatz, L.; Fremouw, W.; Thomas, T.; McCoy, K. Vicious dogs: The antisocial behaviors and psychological characteristics of owners. J. Forensic Sci. 2009, 54, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, B. Dog-focused law’s impact on disability rights: Ontario’s pit bull legislation as a case in point. Anim. L. 2005, 12, 217. [Google Scholar]

- Molloy, C. Dangerous dogs and the construction of risk. In Theorizing Animals: Rethinking Humanimal Relations; Brill Academic Pub: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 107–128. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, P.; Eyck, T.A.T. The social construction of a monster: A lesson from a lecture on race. In Teaching Criminology at the Intersection; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- Iliopoulou, M.A.; Carla, L.C.; Laura, A.R. Beloved companion or problem animal: The shifting meaning of pit bull. Soc. Anim. 2019, 27, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, H.; Anne, L.S. 14 Making distinctions: The social construction of target populations. In Handbook of Critical Policy Studies; Edward Elgar Pub: Gloucestershire, UK, 2015; pp. 259–273. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, G.E. What Are the Best Pollsters in America? ABC News/538: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Available online: https://abcnews.go.com/538/best-pollsters-america/story?id=105563951 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Swanson, E. There’s Still a Lot of Work to be Done for Pit Bulls, Poll Finds; HuffPost: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/pit-bulls-poll_n_5628261 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Ansolabehere, S.; Schaffner, B.; Luks, S. The 2018 Cooperative Congressional Election Survey (CCES); Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- YouGov. American Pit Bull Terrier Fame and Popularity in Q4-2024. 2025. Available online: https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/u7vvbdl38p69z3223p42p/YouGov_American-Pit-Bull-Terrier-Q4_2024.png?rlkey=cxy4i-gtsypzsuhb5r5n2g53s&dl=0 (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- City Code Section 14–75. Ordinance No. 2005-84. Available online: https://aurora.municipal.codes/enactments/Ord2005-84 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Fix, M.P.; Mitchell, J.L. Examining the Policy Learning Dynamics of Atypical Policies with an Application to State Preemption of Local Dog Laws. Stat. Politics Policy 2017, 8, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Canine Research Council. Breed-Specific Legislation Map; National Canine Research Council: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Available online: https://nationalcanineresearchcouncil.com/bsl-map/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- County Code 5-17. Ordinance No. 89-22. Available online: https://library.municode.com/fl/miami_-_dade_county/codes/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=PTIIICOOR_CH5ANFO (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- YouGov. American Pit Bull Terrier Fame and Popularity Tracker. 2025. Available online: https://today.yougov.com/topics/society/trackers/fame-and-popularity-american-pit-bull-terrier (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- YouGov. Staffordshire Bull Terrier Fame and Popularity Tracker. 2025. Available online: https://today.yougov.com/topics/society/trackers/fame-and-popularity-staffordshire-bull-terrier (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Burrows, T.; William, F. Views of College Students on Pit Bull “Ownership”: New Providence, The Bahamas. Soc. Anim. 2005, 13, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity: Youth and Crisis; WW Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Sears, D.O. Political Socialization. In Handbook of Political Science; Fred, I.G., Nelson, W.P., Eds.; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1975; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Krosnick, J.A.; Alwin, D.F. Aging and susceptibility to attitude change. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuman, H.; Steeh, C.; Bobo, L. Racial Attitudes in America: Trends and Interpretations; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub, P.M.; Garretson, J. Getting the message out: Media context and global changes in attitudes toward homosexuality. Comp. Political Stud. 2017, 50, 1055–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, M. Attempt to Repeal Pit Bull Ban Crushed in Colorado; Animals 24-7: Leicestershire, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.animals24-7.org/2014/11/05/attempt-to-repeal-pit-bull-ban-crushed-in-colorado/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- American Canine Foundation v. City of Aurora, Colorado, Civil Action No. 06-cv-01510-WYD-BNB. 8 May 2009. Available online: https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/colorado/codce/1:2006cv01510/97699/159/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- The Sentinal. Aurora Pit Bull Vote Could Spur a National Trend; The Sentinel: Stoke-on-Trent, UK, 2014; Available online: https://sentinelcolorado.com/uncategorized/aurora-pit-bull-vote-spur-national-trend/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- The Sentinal. No on Proposition 2D: Putting an End to Aurora’s Dangerous Pit Bull Charade; The Sentinel: Stoke-on-Trent, UK, 2014; Available online: https://sentinelcolorado.com/opinion/proposition-2d-putting-end-auroras-dangerous-pit-bull-charade/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Ulibarri, L. Aurora Residents Say Yes to Pit Bulls: Breed Ban Repeal Approved in 2024 Election; I’m From Denver: Denver, CO, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.imfromdenver.com/trending/aurora-residents-say-yes-to-pit-bulls-breed-ban-repeal-approved-in-2024-election/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Shipan, C.R.; Volden, C. The mechanisms of policy diffusion. Am. J. Political Sci. 2008, 52, 840–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, J. Miami-Dade Breed Ban Victory: And the Wall Came Tumbling Down; Best Friends Animal Society: Kanab, UT, USA, 2023; Available online: https://bestfriends.org/stories/julie-castle-blog/miami-dade-breed-ban-victory-and-wall-came-tumbling-down (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Brecher, E.J.; In Miami-Dade, pit bulls remain illegal. Miami Herald 2012. Available online: https://www.miamiherald.com/news/politics-government/article1941983.html (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Lilly, C. Mark and Jamie Buehrle Fight to Lift Miami-Dade Pit Bull Ban, Helped by Aspiring Therapy Dog Slater; HuffPost: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/miami-dade-pitbull-ban-mark-buehrle_n_1702261 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Hernandez, C.; Julia, B.; Willard, S. Miami-Dade Residents Vote to Keep Pit Bull Ban Tuesday; NBC-6 South Florida: Miramar, FL, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.nbcmiami.com/news/local/miami-dade-residents-vote-on-pit-bull-ban-repeal-tuesday/1865477/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Available online: https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2025/614 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Available online: https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2023/942 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Available online: https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2023/941 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Spears, D. New Law Prevents Insurance Companies from Discriminating Against Dog Breeds; ABC-13 Las Vegas: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.ktnv.com/13-investigates/new-law-prevents-insurance-companies-from-discriminating-dog-breeds (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Fenster, N.J. CT bill would prevent insurance companies from discriminating against some dog breeds. CT Insider 2025. Available online: https://www.ctinsider.com/connecticut/article/ct-bill-insurance-companies-dog-breeds-premium-20277322.php (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Kogan, L.R.; Regina, M.S.-T.; Peter, W.H.; James, A.O.; Mark, R. Small animal veterinarians’ perceptions, experiences, and views of common dog breeds, dog aggression, and breed-specific laws in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N. Do policy makers listen to experts? Evidence from a national survey of local and state policy makers. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2021, 116, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, D. Calls for Crackdown on Pit Bulls; CBS News: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Available online: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/calls-for-crackdown-on-pit-bulls/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Associated Press. Newsom Pushes Pit Bull Law. East Bay Times 2005. Available online: https://www.eastbaytimes.com/2005/06/21/newsom-pushes-pit-bull-law/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Livingston, M. 2005 battle over pit bulls revived for some dog lovers considering California’s governor’s race. Los Angeles Times, 23 May 2018. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/politics/la-pol-ca-newsom-pit-bulls-20180523-story.html (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Patronek, G.J.; Slater, M.; Marder, A. Use of a number-needed-to-ban calculation to illustrate limitations of breed-specific legislation in decreasing the risk of dog bite–related injury. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2010, 237, 788–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arluke, A.; Donald, C.; Gary, P.; Janis, B. Defaming rover: Error-based latent rhetoric in the medical literature on dog bites. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2018, 21, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxley, J.A.; Rob, C.; Carri, W. Contexts and consequences of dog bite incidents. J. Vet. Behav. 2018, 23, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, L.A.; Vertalka, J.J. Understanding dog bites: The important role of human behavior. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2021, 24, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilens, M. Why Americans Hate Welfare: Race, Media, and the Politics of Anti-Poverty Policy; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, N.J.G. Dangerous frames: How Ideas about Race & Gender Shape Public Opinion; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kinder, D.R.; Cindy, D.K. Us Against Them: Ethnocentric Foundations of American Opinion; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Raychaudhuri, T.; Mendelberg, T.; McDonough, A. The political effects of opioid addiction frames. J. Politics 2023, 85, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, F. Pit Bull Breed Ban Abolished in Tijeras. 2020. Available online: https://www.pressreader.com/usa/the-independent-usa/20200710/281487868644147 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

| American Pit Bull Terrier | Staffordshire Bull Terrier | |

|---|---|---|

| Quarter of Survey | 0.459 (0.070) | 0.414 (0.075) |

| Constant | 50.11 (0.633) | 43.96 (0.683) |

| R2 | 0.767 | 0.700 |

| Number of Quarters | 15 | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tesler, M.; McThomas, M. How Changing Portraits and Opinions of “Pit Bulls” Undermined Breed-Specific Legislation in the United States. Animals 2025, 15, 2083. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15142083

Tesler M, McThomas M. How Changing Portraits and Opinions of “Pit Bulls” Undermined Breed-Specific Legislation in the United States. Animals. 2025; 15(14):2083. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15142083

Chicago/Turabian StyleTesler, Michael, and Mary McThomas. 2025. "How Changing Portraits and Opinions of “Pit Bulls” Undermined Breed-Specific Legislation in the United States" Animals 15, no. 14: 2083. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15142083

APA StyleTesler, M., & McThomas, M. (2025). How Changing Portraits and Opinions of “Pit Bulls” Undermined Breed-Specific Legislation in the United States. Animals, 15(14), 2083. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15142083