Worth the Effort? Rehabilitation Causes and Outcomes and the Assessment of Post-Release Survival for Urban Wild Bird Admissions in a European Metropolis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

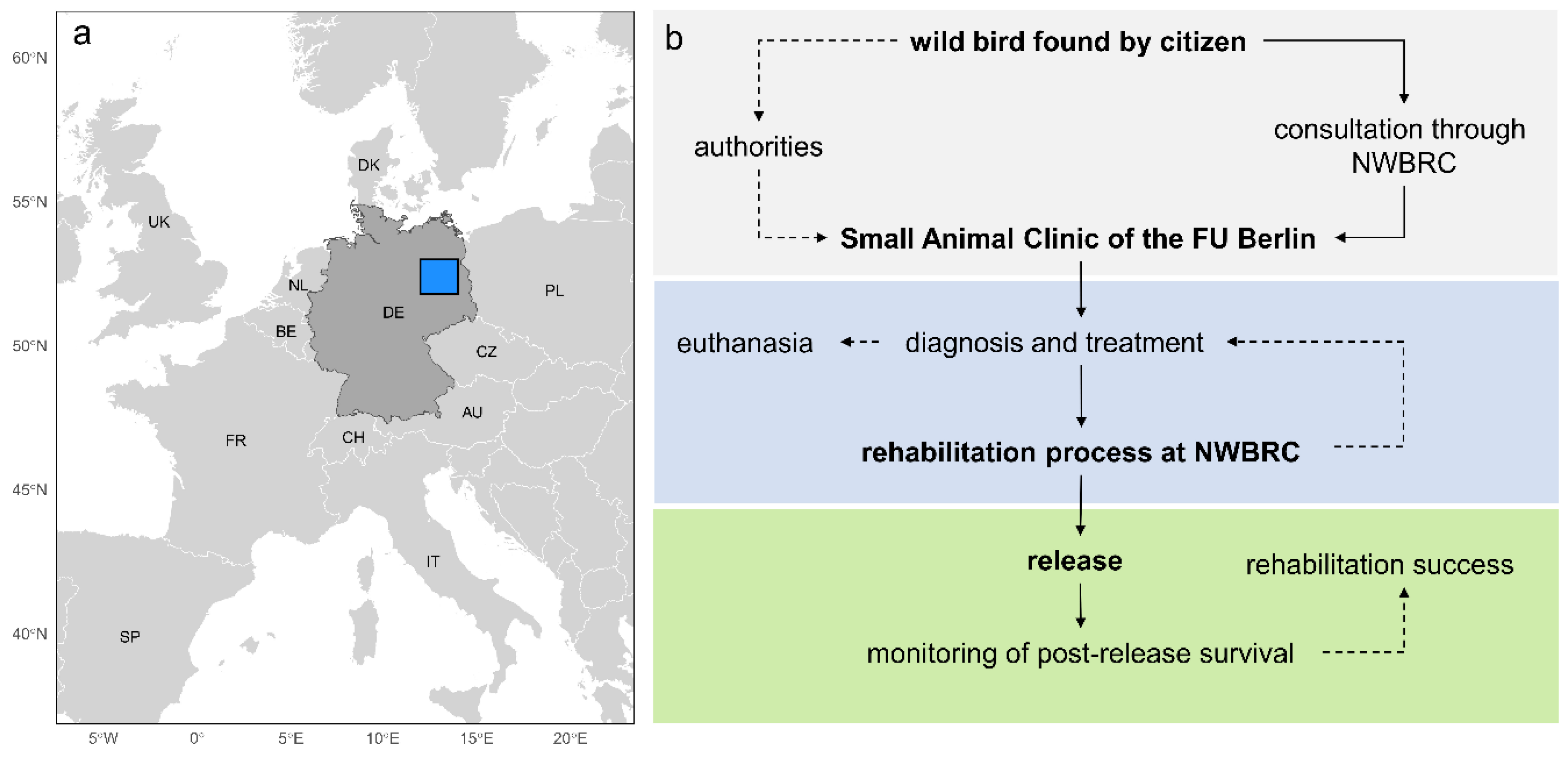

2.1. Study Background and Area

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Causes and Demographics of Admissions

2.4. Rehabilitation Duration and Outcome for Admissions

2.5. Assessment of Post-Release Survival and Rehabilitation Success

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Causes and Demographics of Admissions

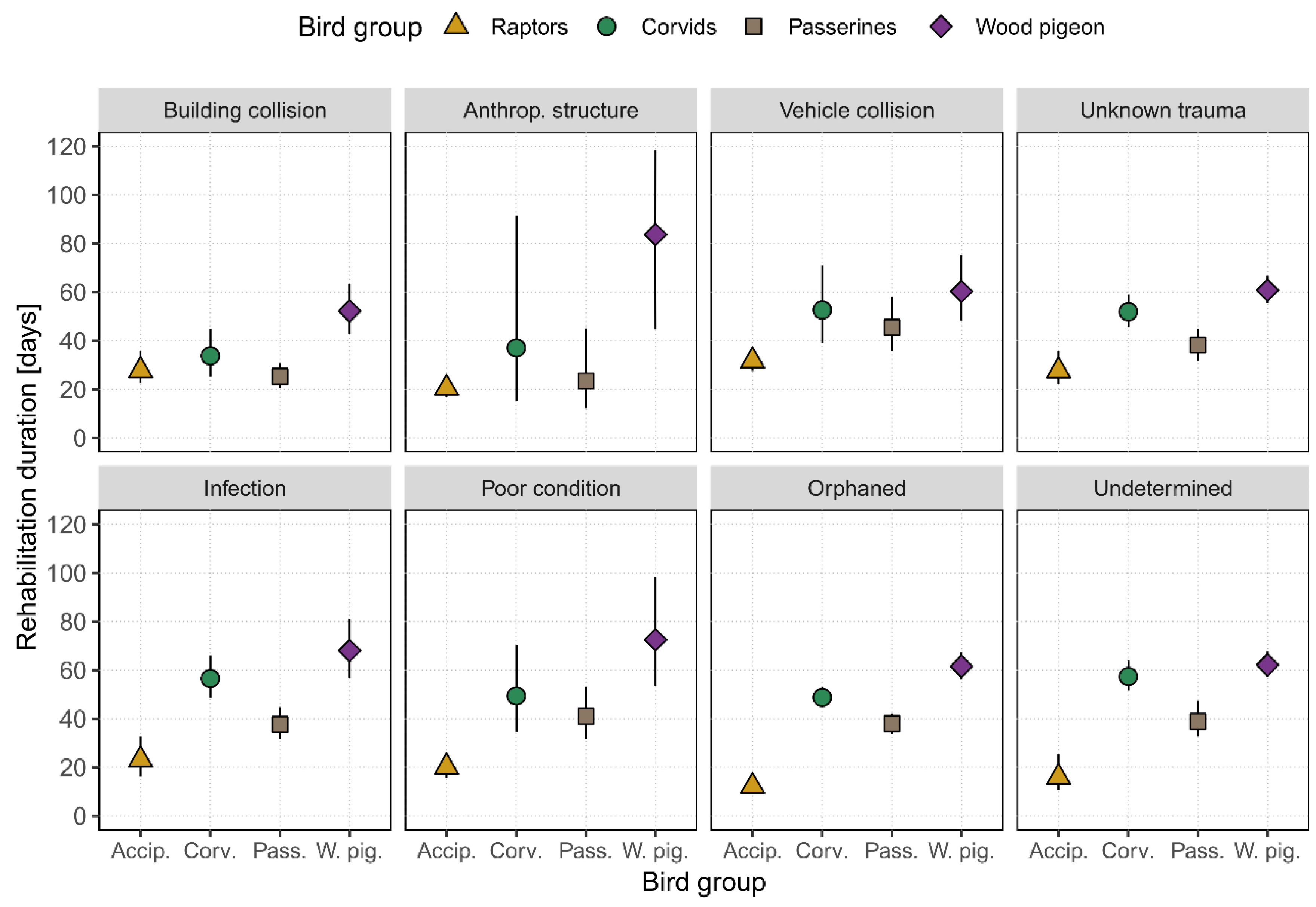

3.2. Rehabilitation Duration for Admissions

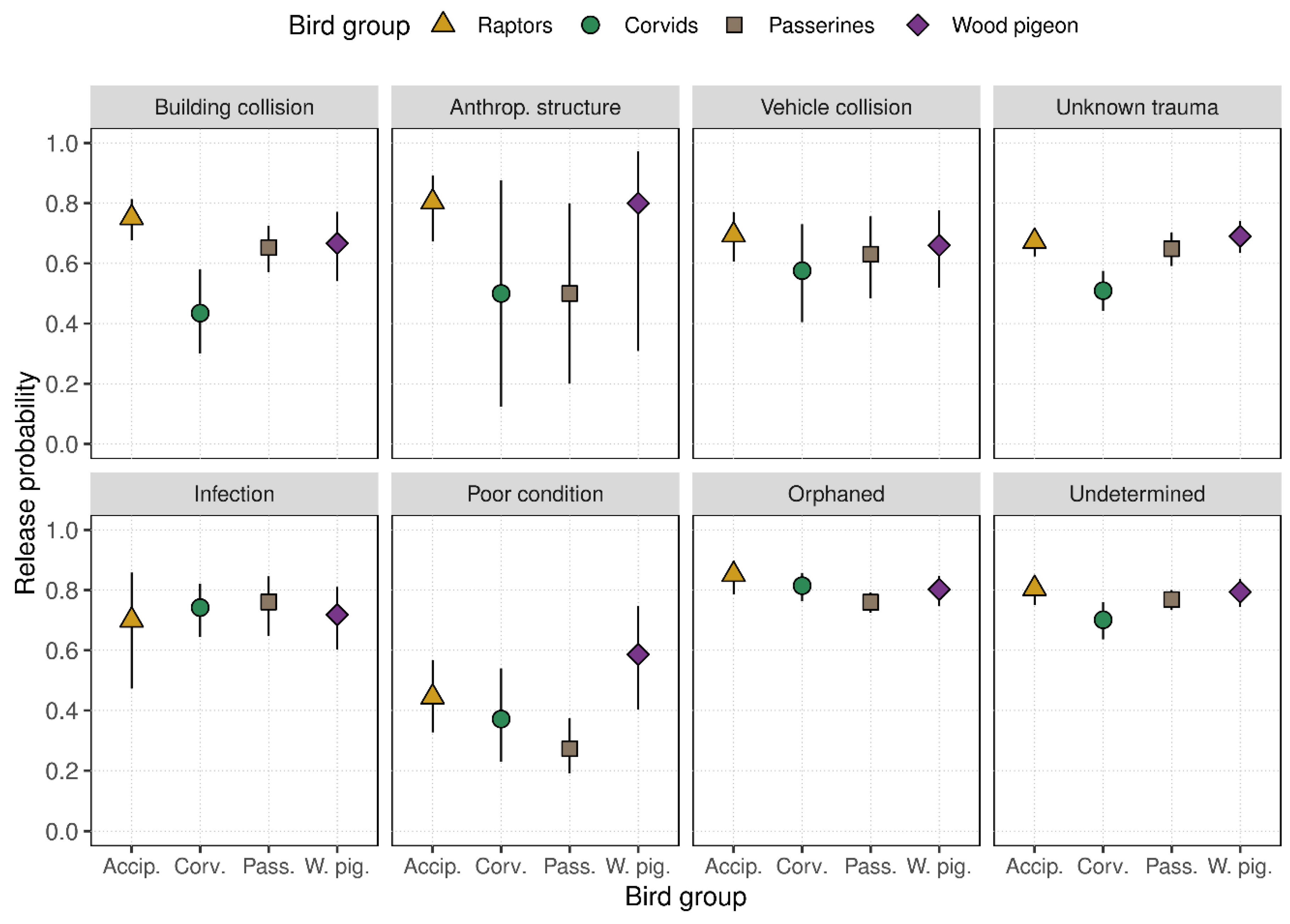

3.3. Outcomes of Rehabilitation

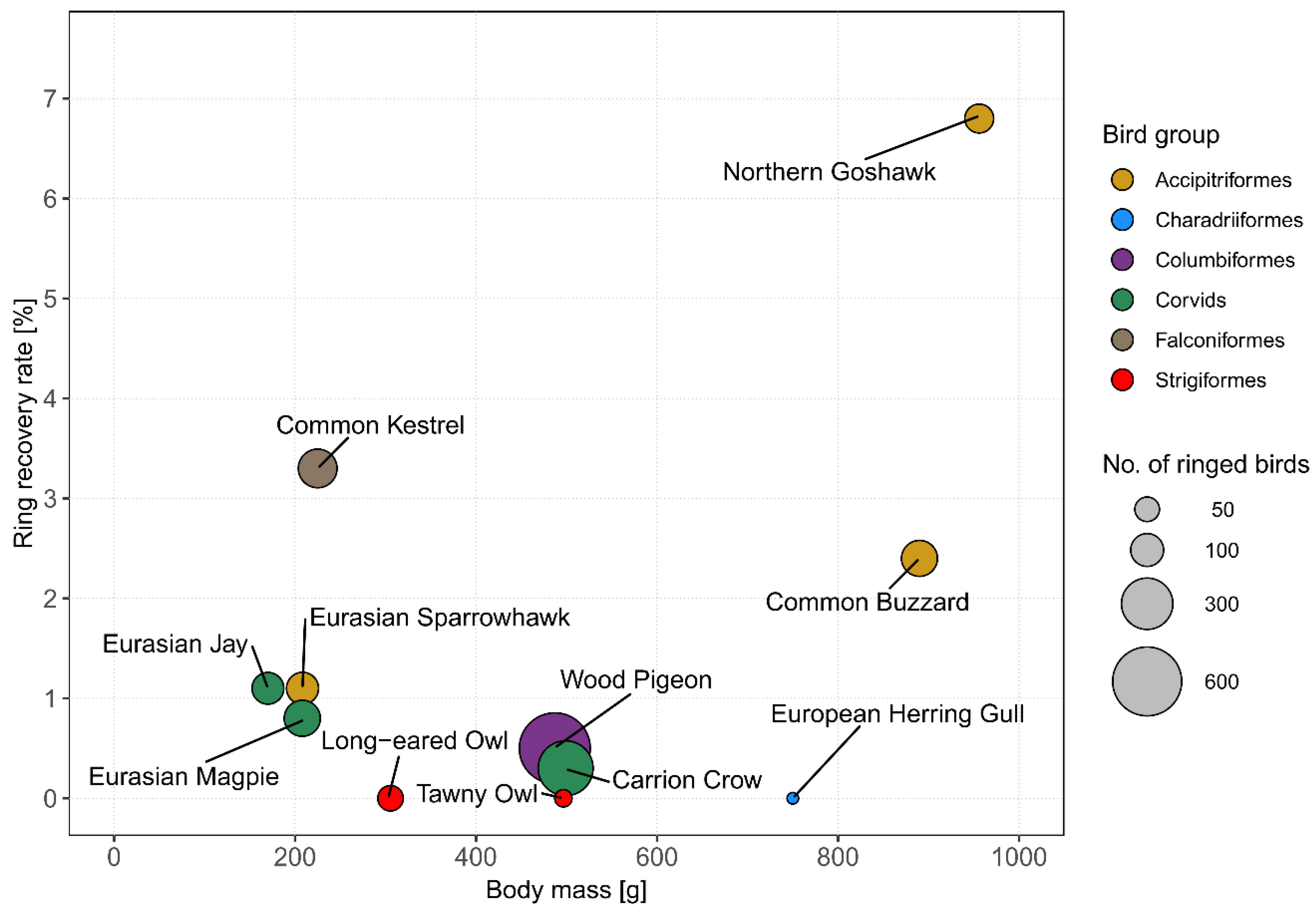

3.4. Post-Release Survival and Rehabilitation Success

4. Discussion

4.1. Causes and Demographics of Admissions

4.2. Rehabilitation Duration and Outcomes of Admissions

4.3. Post-Release Survival and Rehabilitation Success

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pyke, G.H.; Szabo, J.K. Conservation and the 4 Rs, Which Are Rescue, Rehabilitation, Release, and Research. Conserv. Biol. 2018, 32, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, R.; Bateman, H.L.; Larson, K.L.; Herzog, C.; Brown, J.A. To the Rescue—Evaluating the Social-Ecological Patterns for Bird Intakes. Urban Ecosyst. 2022, 25, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.; Cooper, M.E. Ethical and Legal Implications of Treating Casualty Wild Animals. In Pract. 2006, 28, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribe, A.; Brown, P.R. The Role of Wildlife Rescue Groups in the Care and Rehabilitation of Australian Fauna. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2000, 5, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, M.; Chavez, R.; Sens, R.; Lundberg, M.; Delor, A.; Rousset, F.; Courtiol, A. Breeding Site Fidelity in the Concrete Jungle: Implications for the Management of Urban Mallards. J. Urban Ecol. 2025, 11, juae023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleeman, J.M. Chapter 12—Use of Wildlife Rehabilitation Centers as Monitors of Ecosystem Health. In Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine; Fowler, M.E., Miller, R.E., Eds.; W.B. Saunders: Saint Louis, MO, USA, 2008; pp. 97–104. ISBN 978-1-4160-4047-7. [Google Scholar]

- Wendell, M.D.; Sleeman, J.M.; Kratz, G. Retrospective Study of Morbidity and Mortality of Raptors Admitted to Colorado State University Veterinary Teaching Hospital during 1995 to 1998. J. Wildl. Dis. 2002, 38, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessalvi, G.; Borgo, E.; Galli, L. The Contribution to Wildlife Conservation of an Italian Recovery Centre. Nat. Conserv. 2021, 44, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monadjem, A.; Wolter, K.; Neser, W.; Kane, A. Effect of Rehabilitation on Survival Rates of Endangered Cape Vultures. Anim. Conserv. 2014, 17, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sleeman, J.M.; Clark, E.E. Clinical Wildlife Medicine: A New Paradigm for a New Century. J. Avian Med. Surg. 2003, 17, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.R.; Brown, M.B. Where Has All the Road Kill Gone? Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 233–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusa, M.; Jackson, D.; Mesure, M.; Ecosyst, U. Window Collisions by Migratory Bird Species: Urban Geographical Patterns and Habitat Associations. Urban Ecosyst. 2015, 18, 1427–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainwaring, M.C. The Use of Man-Made Structures as Nesting Sites by Birds: A Review of the Costs and Benefits. J. Nat. Conserv. 2015, 25, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panter, C.; Allen, S.; Backhouse, N.; Mullineaux, E.; Rose, C.; Amar, A. Causes, Temporal Trends, and the Effects of Urbanization on Admissions of Wild Raptors to Rehabilitation Centers in England and Wales. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, 8856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegworth, C. Vogelschutz und Glasarchitektur im Stadtraum Berlin. Eine Aktuelle Bestandsaufnahme und Ermittlung von Erfordernissen für Eine Verantwortungsvolle Stadtplanung; BUND für Umwelt- und Naturschutz (BUND): Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Loss, S.R.; Will, T.; Marra, P.P. The Impact of Free-Ranging Domestic Cats on Wildlife of the United States. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loyd, K.A.T.; Hernandez, S.M.; McRuer, D.L. The Role of Domestic Cats in the Admission of Injured Wildlife at Rehabilitation and Rescue Centers. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2017, 41, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullineaux, E.; Pawson, C. Trends in Admissions and Outcomes at a British Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre over a Ten-Year Period (2012–2022). Animals 2023, 14, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badry, A.; Krone, O.; Jaspers, V.L.B.; Mateo, R.; García-Fernández, A.; Leivits, M.; Shore, R.F. Towards Harmonisation of Chemical Monitoring Using Avian Apex Predators: Identification of Key Species for Pan-European Biomonitoring. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 731, 139198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badry, A.; Schenke, D.; Treu, G.; Krone, O. Linking Landscape Composition and Biological Factors with Exposure Levels of Rodenticides and Agrochemicals in Avian Apex Predators from Germany. Environ. Res. 2021, 193, 110602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krone, O.; Sömmer, P.; Lessow, P.; Haas, D. Causes of Death, Diseases and Parasites in Common Buzzards Buteo Buteo from Germany. Popul. Greifvogel Eulenarten 2006, 5, 439–448. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Merling de Chapa, M.; Auls, S.; Kenntner, N.; Krone, O. To Get Sick or Not to Get Sick—Trichomonas Infections in Two Accipiter Species from Germany. Parasitol. Res. 2021, 120, 3555–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, F.; Espinoza, A.; Sallaberry-Pincheira, N.; Napolitano, C. A Five-Year Retrospective Study on Patterns of Casuistry and Insights on the Current Status of Wildlife Rescue and Rehabilitation Centers in Chile. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 2019, 92, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, V.K.; Jones, D.; McBroom, J.; Lilleyman, A.; Pyne, M. Hospital Admissions of Australian Coastal Raptors Show Fishing Equipment Entanglement Is an Important Threat. J. Raptor Res. 2020, 54, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-López, R.A.; Casal, J.; Darwich, L. Causes of Morbidity in Wild Raptor Populations Admitted at a Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre in Spain from 1995–2007: A Long Term Retrospective Study. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, H.; Mcarthur, C.; Dickman, C.; Newsome, T.; Gray, R.; Herbert, C. A Systematic Review of Factors Affecting Wildlife Survival during Rehabilitation and Release. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, B.E. Post-Release Survival of Oiled, Cleaned Seabirds in North America. Ibis 1996, 138, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardo, I.; Babiloni, G.; Miranda, Y. Rehabilitated and Wild Barn Owls (Tyto alba): Dispersal, Life Expectancy and Mortality in Spain. Biol. Conserv. 2000, 94, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Tuohetahong, Y.; Lin, F.; Dong, R.; Wang, H.; Wu, X.; Ye, X.; Yu, X. Factors Affecting Post-Release Survival and Dispersal of Reintroduced Crested Ibis (Nipponia nippon) in Tongchuan City, China. Avian Res. 2022, 13, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Lopez, R.; Darwich, L. Causes of Admission of Little Owl (Athene noctua) at a Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre in Catalonia (Spain) from 1995 to 2010. Anim. Biodivers. Conserv. 2011, 34, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2025-1. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior—Vogelwarte Radolfzell. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.ab.mpg.de/vogelwarte (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Rousset, F.; Ferdy, J.-B. Testing Environmental and Genetic Effects in the Presence of Spatial Autocorrelation. Ecography 2014, 37, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, F. DHARMa: Residual Diagnostics for Hierarchical (Multi-Level/Mixed) Regression Models_. R Package Version 0.4.7. 2024. Available online: http://florianhartig.github.io/DHARMa/ (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team R: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, J.; Crespo, J.; Martínez-Abraín, A. Long-Term Shifts in Admissions of Birds to Wildlife Recovery Centres Reflect Changes in Societal Attitudes towards Wildlife. Ardeola Int. J. Ornithol. 2022, 69, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, P.S.; Bandivadekar, R.R.; Johnson, C.K.; Mikoni, N.; Mah, M.; Purdin, G.; Ibarra, E.; Tom, D.; Daugherty, A.; Lipman, M.W.; et al. Retrospective Study on Admission Trends of Californian Hummingbirds Found in Urban Habitats (1991–2016). PeerJ 2021, 9, e11131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vezyrakis, A.; Bontzorlos, V.; Rallis, G.; Ganoti, M. Two Decades of Wildlife Rehabilitation in Greece: Major Threats, Admission Trends and Treatment Outcomes from a Prominent Rehabilitation Centre. J. Nat. Conserv. 2023, 73, 126372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, C.L. Retrospective Study of Raptors Treated at the Southeastern Raptor Center in Auburn, Alabama. J. Raptor Res. 2018, 52, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, M.; Hollingshead, N.; Schuler, K.; Siemer, W.F.; Martin, P.; Bunting, E.M. Species, Causes, and Outcomes of Wildlife Rehabilitation in New York State. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Kross, S.M.; Parkins, K.; Seewagen, C.; Farnsworth, A.; Van Doren, B.M. Heavy Migration Traffic and Bad Weather Are a Dangerous Combination: Bird Collisions in New York City. J. Appl. Ecol. 2024, 61, 784–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.M.; Pinto da Cunha, N.; Hagnauer, I.; Venegas, M. A Retrospective Analysis of Admission Trends and Outcomes in a Wildlife Rescue and Rehabilitation Center in Costa Rica. Animals 2024, 14, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, A.B.C.; Haering, R.; Travers, S.K.; Stathis, P. Trends in Wildlife Rehabilitation Rescues and Animal Fate across a Six-Year Period in New South Wales, Australia. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukesova, G.; Voslarova, E.; Vecerek, V.; Vucinic, M. Causes of Admission, Length of Stay and Outcomes for Common Kestrels in Rehabilitation Centres in the Czech Republic. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.; Halstead, C.; Hunter, D.; Leighton, K.; Grogan, A.; Harris, M. Factors Affecting the Likelihood of Release of Injured and Orphaned Woodpigeons (Columba palumbus). Anim. Welf. 2011, 20, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, P. Breeding Ecology of a Suburban Population of Woodpigeons Columba palumbus in Northwest England. Bird Study 2001, 48, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-López, R.A.; Casal, J.; Darwich, L. Final Disposition and Quality Auditing of the Rehabilitation Process in Wild Raptors Admitted to a Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre in Catalonia, Spain, during a Twelve Year Period (1995–2007). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, N.J.; Vanstreels, R.E.T.; Schaefer, A.M. Prognostic indicators of rehabilitation outcomes for adult african penguins (Spheniscus demersus). J. Wildl. Dis. 2018, 54, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-López, R.A.; Mañosa, S.; Torres-Riera, A.; Pomarol, M.; Darwich, L. Morbidity, Outcomes and Cost-Benefit Analysis of Wildlife Rehabilitation in Catalonia (Spain). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochet, A.-L.; Bossche, W.; Ndang’ang’a, P.; Jones, V.; Abdou, W.; Hmoud, A.; Asswad, N.; Atienza, J.C.; Atrash, I.; Barbara, N.; et al. Preliminary Assessment of the Scope and Scale of Illegal Killing and Taking of Birds in the Mediterranean. Bird Conserv. Int. 2016, 1, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmyn, A.; Rouffaer, L.; Roggeman, T.; Verlinden, M.; Hermans, K.; Cools, M.; Van den Meersschaut, M.; Croubels, S.; Martel, A. Persecution of Birds of Prey in Flanders: A Retrospective Study 2011–19. J. Wildl. Dis. 2021, 57, 922–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duke, G.E.; Redig, P.T.; Jones, W. Recoveries and Resightings of Released Rehabilitated Raptors. J. Raptor Res. 1981, 15, 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Joys, A.C.; Clark, J.A.; Clark, N.A.; Robinson, R.A. An Investigation of the Effectiveness of Rehabilitation of Birds as Shown by Ringing Recoveries; British Trust for Ornithology: Norfolk, UK, 2003; p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, R.; Grantham, M.; Clark, J. Declining Rates of Ring Recovery in British Birds. Ringing Migr. 2009, 24, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, C.A.; Goodell, J.M.; Millsap, B.A.; Zimmerman, G.S. ‘Dead Birds Flying’: Can North American Rehabilitated Raptors Released into the Wild Mitigate Anthropogenic Mortality? Wildl. Biol. 2024, 2024, e01283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerr, R.; Jaques, D.; Selby, B.; Skoglund, J.; Kosina, S. Medical history and post-release survival of rehabilitated california brown pelicans Pelecanus occidentalis californicus, 2009–2019. Mar. Ornithol. 2023, 51, 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Prosser, P.; Nattrass, C.; Prosser, C. Rate of Removal of Bird Carcasses in Arable Farmland by Predators and Scavengers. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2008, 71, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozsypalová, L.; Literák, I.; Raab, R.; Peške, L.; Krone, O.; Škrábal, J.; Gries, B.; Meyburg, B.-U. Survival of White-Tailed Eagles Tracked After Rehabilitation and Release. J. Raptor Res. 2024, 59, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, J.E.; Deelen, T.R.V.; Berres, M.E. Survival of Rehabilitated and Released Red-Tailed Hawks (Buteo jamaicensis). Wildl. Rehabil. Bull. 2020, 38, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Build | Struct | Vehic | Trauma | Persec | Pet | Infect | Condit | Orph | Undet | TOTAL (%) | Rehabilitation Effort (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common Buzzard | 23 (10) | 7 (3) | 33 (15) | 101 (45) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 4 (2) | 20 (9) | 11 (5) | 25 (11) | 225 (4) | 4316 (3) |

| Eurasian Sparrowhawk | 33 (21) | 4 (2) | 18 (11) | 50 (31) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (2) | 2 (1) | 13 (8) | 36 (22) | 160 (3) | 2830 (2) |

| Northern Goshawk | 22 (12) | 16 (9) | 14 (8) | 66 (35) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 8 (4) | 10 (5) | 21 (11) | 27 (15) | 186 (4) | 3232 (2) |

| Accipitriformes | 79 (13) | 27 (4) | 69 (11) | 238 (39) | 2 (0) | 1 (0) | 17 (3) | 34 (6) | 45 (7) | 101 (16) | 613 (12) | 11,022 (7) |

| Carrion Crow | 24 (4) | 3 (1) | 19 (3) | 147 (26) | 3 (1) | 5 (1) | 50 (9) | 25 (4) | 166 (29) | 123 (22) | 565 (11) | 24,190 (15) |

| Eurasian Jay | 7 (5) | 1 (1) | 5 (3) | 30 (20) | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | 12 (8) | 6 (4) | 44 (29) | 43 (28) | 153 (3) | 4850 (3) |

| Eurasian Magpie | 15 (8) | 0 (0) | 6 (3) | 34 (19) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 31 (17) | 3 (2) | 45 (25) | 42 (23) | 180 (4) | 6144 (4) |

| Corvids | 46 (5) | 4 (0) | 33 (4) | 216 (24) | 6 (1) | 11 (1) | 93 (10) | 35 (4) | 259 (28) | 211 (23) | 914 (18) | 35,798 (23) |

| Common Kestrel | 29 (8) | 9 (3) | 32 (9) | 73 (20) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 21 (6) | 86 (24) | 105 (29) | 359 (7) | 6542 (4) |

| Falconiformes | 32 (9) | 11 (3) | 33 (9) | 77 (21) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 23 (6) | 86 (23) | 109 (29) | 375 (7) | 6734 (4) |

| Common Blackbird | 23 (5) | 1 (0) | 13 (3) | 72 (15) | 0 (0) | 32 (7) | 43 (9) | 11 (2) | 144 (30) | 136 (29) | 475 (9) | 12,228 (8) |

| Common Starling | 6 (5) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 15 (13) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 7 (6) | 8 (7) | 27 (24) | 45 (39) | 114 (2) | 2517 (2) |

| Great Tit | 7 (5) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 15 (10) | 0 (0) | 4 (3) | 8 (5) | 8 (5) | 55 (35) | 54 (35) | 155 (3) | 3401 (2) |

| Greenfinch | 8 (6) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 21 (15) | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | 5 (4) | 5 (4) | 58 (41) | 38 (27) | 140 (3) | 3877 (2) |

| House Sparrow | 36 (7) | 2 (0) | 13 (2) | 82 (15) | 0 (0) | 14 (3) | 1 (0) | 28 (5) | 186 (35) | 175 (33) | 537 (11) | 18,712 (12) |

| Passerines | 144 (7) | 8 (0) | 46 (2) | 282 (14) | 5 (0) | 69 (4) | 71 (4) | 88 (5) | 608 (31) | 627 (32) | 1948 (38) | 52,117 (33) |

| Long-Eared Owl | 27 (26) | 4 (4) | 9 (9) | 35 (33) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 11 (10) | 14 (13) | 105 (2) | 1379 (1) |

| Strigiformes | 42 (22) | 13 (7) | 19 (10) | 55 (28) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 6 (3) | 24 (12) | 31 (16) | 195 (4) | 3005 (2) |

| Wood Pigeon | 63 (6) | 5 (0) | 50 (5) | 284 (27) | 2 (0) | 19 (2) | 71 (7) | 29 (3) | 243 (23) | 291 (28) | 1057 (21) | 50,065 (32) |

| Total | 406 (8) | 68 (1) | 250 (5) | 1152 (23) | 21 (0) | 100 (2) | 255 (5) | 215 (4) | 1265 (25) | 1370 (27) | 5102 (100) | 158,741 (100) |

| Admission Cause | Released (%/Cause) | Deceased/Euthanised (%/Cause) | Rehabilitation Duration (Days *) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Building collision | 271 (67) | 135 (33) | 28 ± 19 (1–163) | 406 (8) |

| Anthrop. structure | 51 (75) | 17 (25) | 16 ± 18 (1–142) | 68 (1) |

| Vehicle collision | 165 (66) | 85 (34) | 38 ± 21 (3–174) | 250 (5) |

| Unknown trauma | 738 (64) | 414 (36) | 36 ± 22 (1–194) | 1152 (23) |

| Persecution | 11 (52) | 10 (48) | 39 ± 37 (9–99) | 21 (0) |

| Pet attack | 55 (55) | 45 (45) | 37 ± 19 (1–123) | 100 (2) |

| Infection | 188 (74) | 67 (26) | 47 ± 25 (1–186) | 255 (5) |

| Poor overall condition | 82 (38) | 133 (62) | 32 ± 28 (1–167) | 215 (4) |

| Orphaned | 1000 (79) | 265 (21) | 36 ± 22 (1–197) | 1265 (25) |

| Undetermined | 1055 (77) | 315 (23) | 37 ± 22 (1–194) | 1370 (27) |

| Total admissions | 3616 (71) | 1486 (29) | 36 ± 22 (1–197) | 5102 (100) |

| Ringing | Post-Release Survival | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bird Group | Species | Ringed | Ringed + Recovered | Ring Recov. Rate (%) | Successful (%/Ringed) | Failed (%/Ringed) | Unknown (%/Ringed) |

| Accipitriformes | Common Buzzard | 125 | 3 | 2.4 | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 122 (97) |

| Eurasian Sparrowhawk | 94 | 1 | 1.1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 94 (100) | |

| Northern Goshawk | 73 | 5 | 6.8 | 3 (4) | 2 (2) | 68 (93) | |

| Charadriiformes | European Herring Gull | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 20 (100) |

| Pelecaniformes | Grey Heron | 15 | 4 | 26.7 | 4 (26) | 0 (0) | 11 (73) |

| Columbiformes | Wood Pigeon | 641 | 3 | 0.5 | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 640 (99) |

| Falconiformes | Common Kestrel | 150 | 5 | 3.3 | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 147 (98) |

| Corvids | Carrion Crow | 351 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 350 (99) |

| Eurasian Jay | 92 | 1 | 1.1 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 91 (98) | |

| Eurasian Magpie | 126 | 1 | 0.8 | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 125 (99) | |

| Strigiformes | Long-Eared Owl | 54 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 54 (100) |

| Tawny Owl | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 26 (100) | |

| Total | 1767 | 24 | 1.3 | 16 (1) | 3 (0) | 1748 (99) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Engler, M.; Sens, R.; Lundberg, M.; Delor, A.; Stelter, M.; Tschertner, M.; Feyer, S.; Zein, S.; Halter-Gölkel, L.; Altenkamp, R.; et al. Worth the Effort? Rehabilitation Causes and Outcomes and the Assessment of Post-Release Survival for Urban Wild Bird Admissions in a European Metropolis. Animals 2025, 15, 1746. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15121746

Engler M, Sens R, Lundberg M, Delor A, Stelter M, Tschertner M, Feyer S, Zein S, Halter-Gölkel L, Altenkamp R, et al. Worth the Effort? Rehabilitation Causes and Outcomes and the Assessment of Post-Release Survival for Urban Wild Bird Admissions in a European Metropolis. Animals. 2025; 15(12):1746. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15121746

Chicago/Turabian StyleEngler, Marc, Rebekka Sens, Maja Lundberg, Alexandra Delor, Marco Stelter, Malte Tschertner, Sina Feyer, Stephanie Zein, Lesley Halter-Gölkel, Rainer Altenkamp, and et al. 2025. "Worth the Effort? Rehabilitation Causes and Outcomes and the Assessment of Post-Release Survival for Urban Wild Bird Admissions in a European Metropolis" Animals 15, no. 12: 1746. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15121746

APA StyleEngler, M., Sens, R., Lundberg, M., Delor, A., Stelter, M., Tschertner, M., Feyer, S., Zein, S., Halter-Gölkel, L., Altenkamp, R., & Müller, K. (2025). Worth the Effort? Rehabilitation Causes and Outcomes and the Assessment of Post-Release Survival for Urban Wild Bird Admissions in a European Metropolis. Animals, 15(12), 1746. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15121746