Pet Wellness and Vitamin A: A Narrative Overview

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Historical perspective on vitamin A in pet nutrition;

- Digestion and metabolism of vitamin A;

- Physiological role of vitamin A;

- Vitamin A deficiency and excess in pets;

- Interactions with other micronutrients;

- Comparing vitamin A requirements: livestock vs. pets;

- Future directions and research gaps.

2. Historical Perspective on Vitamin A in Pet Nutrition

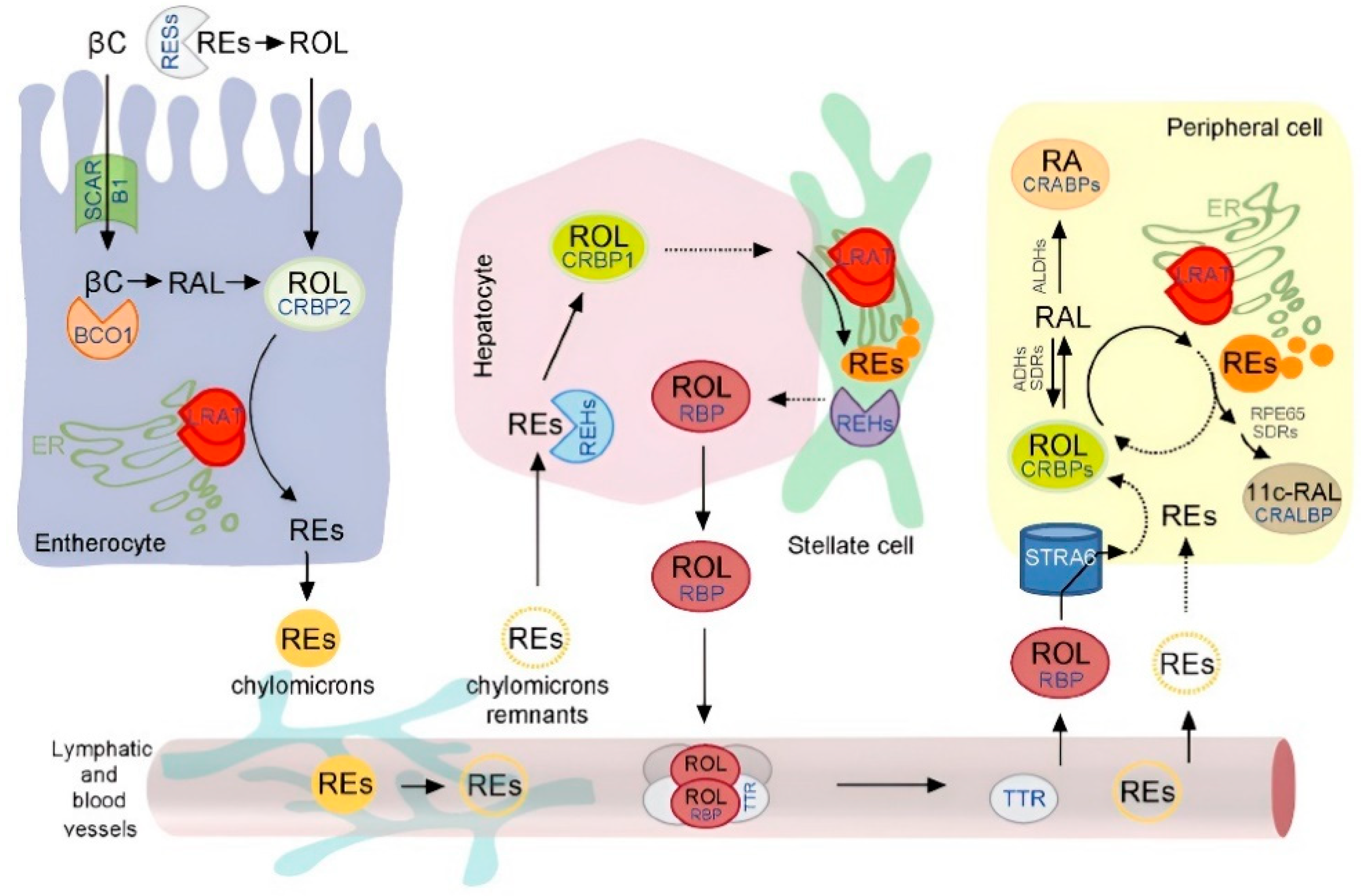

3. Digestion and Metabolism of Vitamin A

4. Physiological Roles of Vitamin A

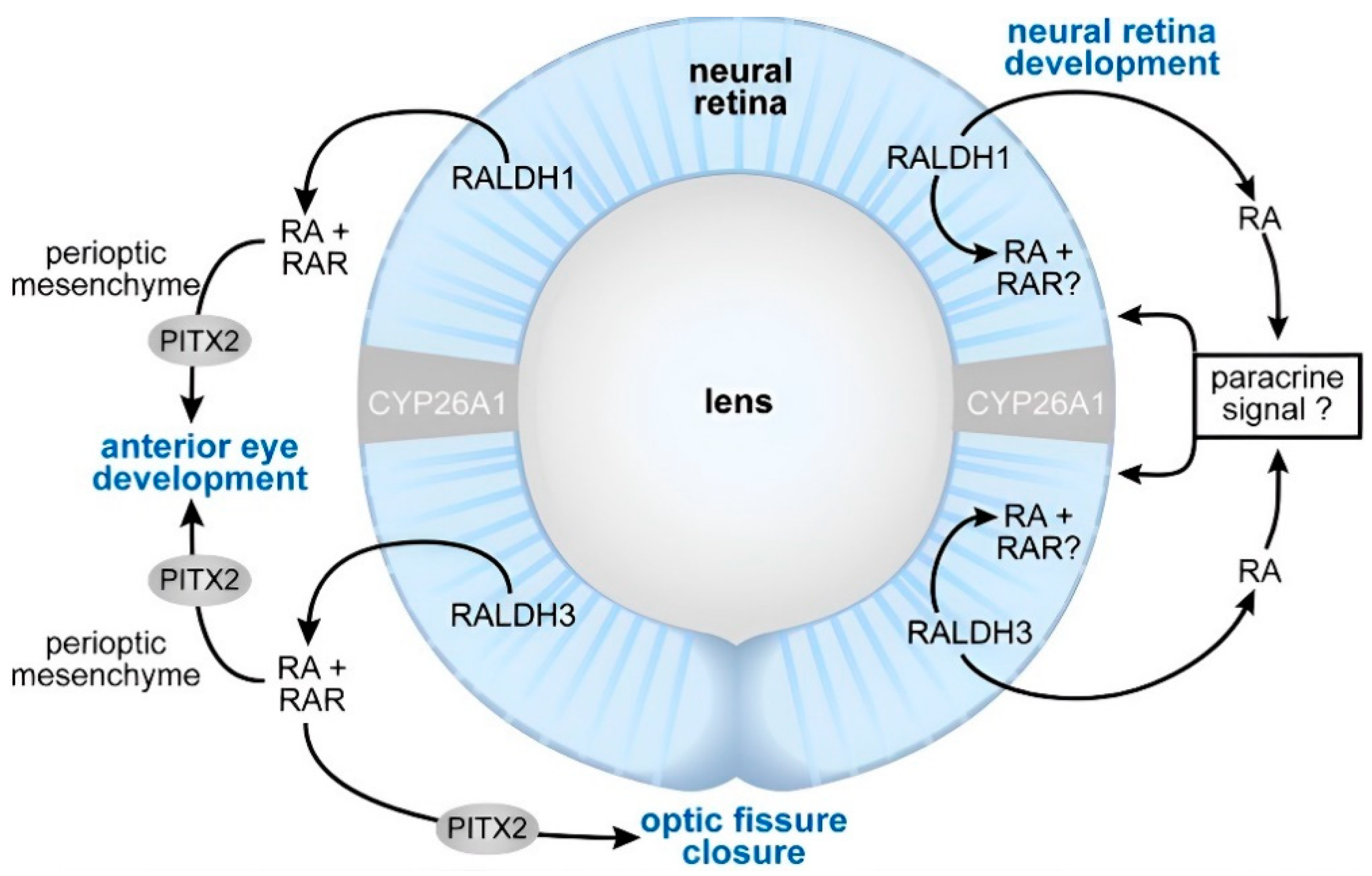

4.1. Vision

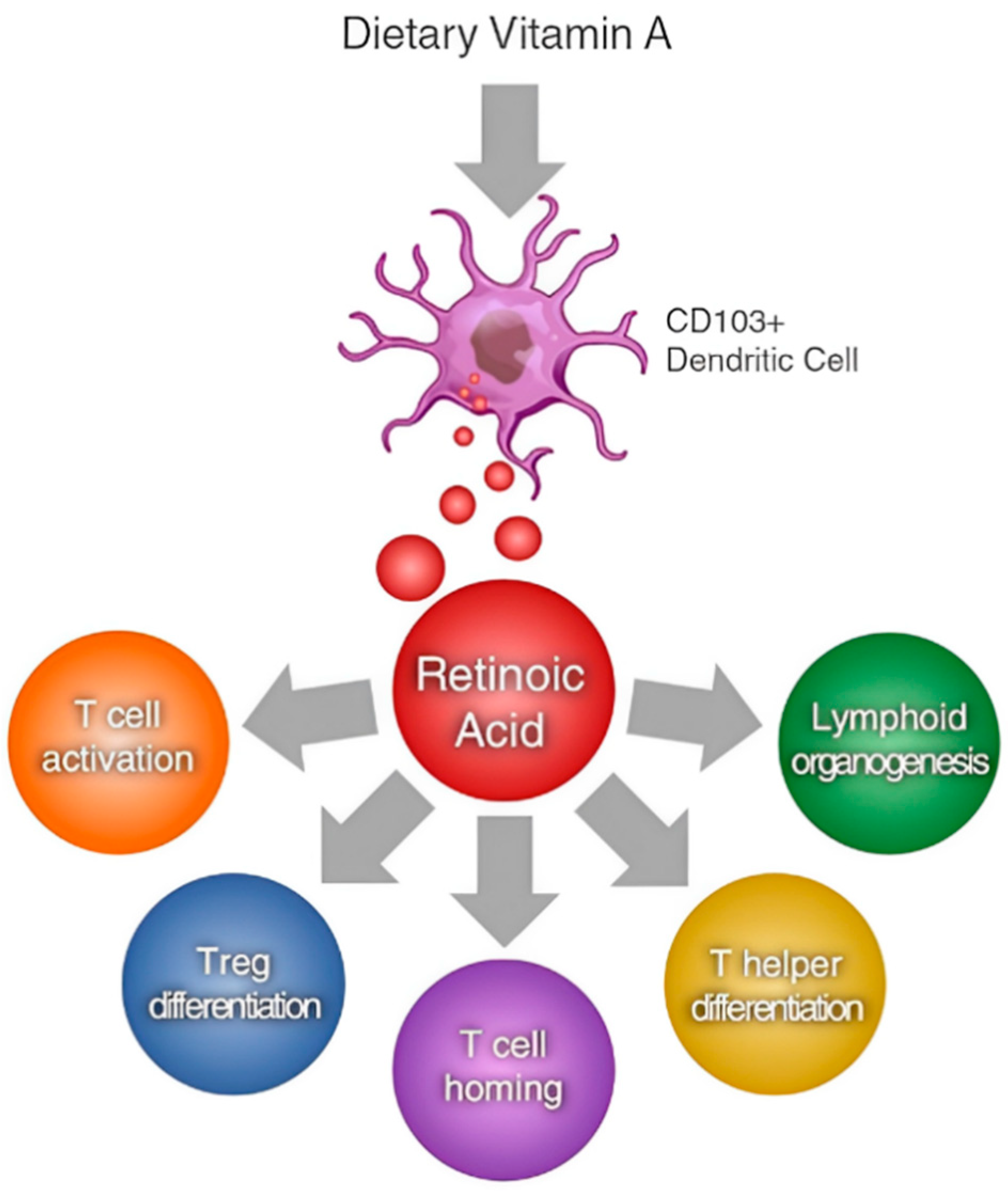

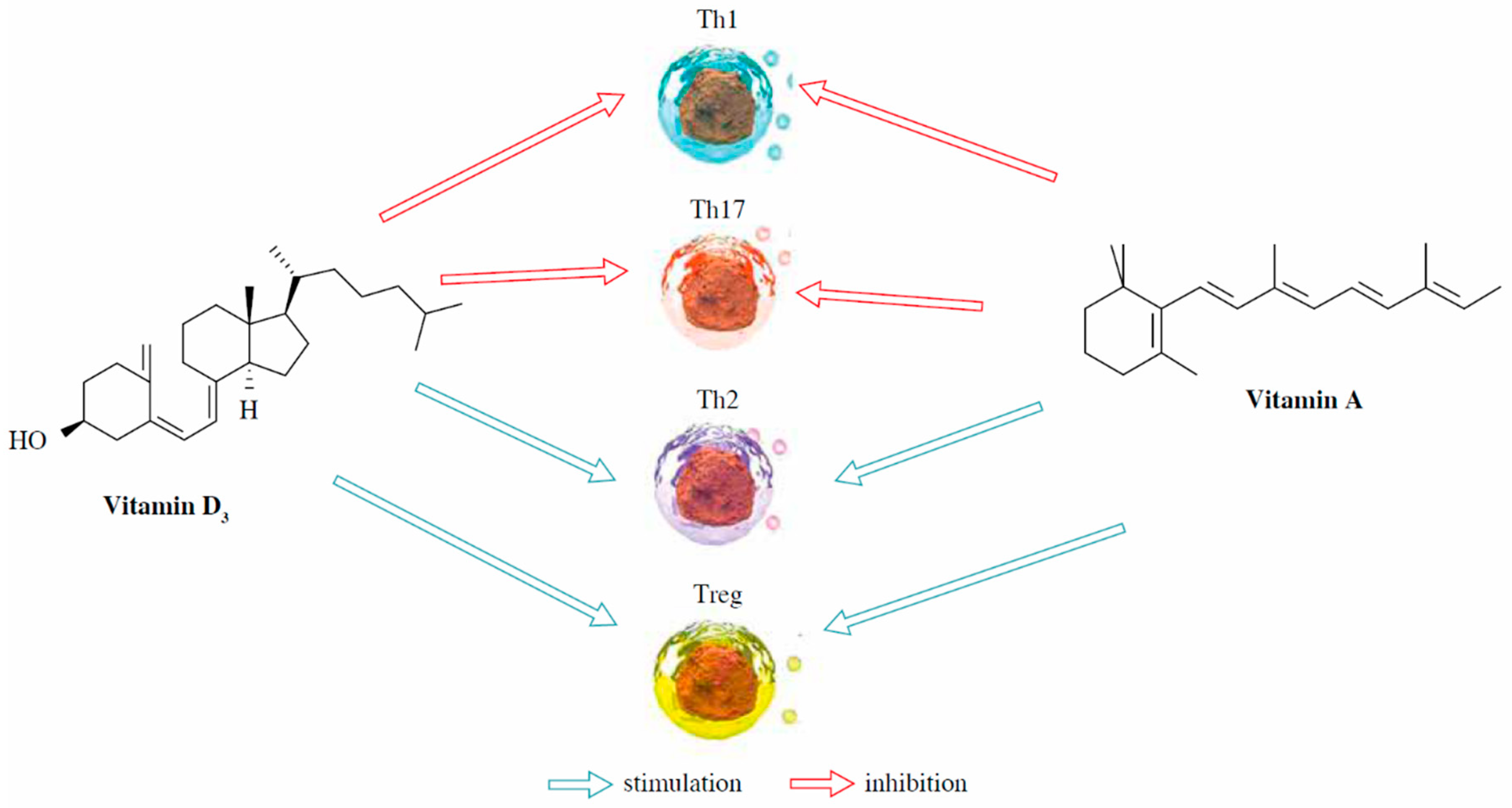

4.2. Immune Function

4.3. Growth, Cellular Differentiation, Morphogenesis, and Reproductive Health

4.4. Antioxidant Properties

5. Vitamin A Deficiency and Excess in Pets

5.1. Vitamin A Deficiency

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5.2. Vitamin A Excess

6. Interactions with Other Micronutrients

6.1. Vitamin A and Vitamin D

6.2. Vitamin A and Vitamin E

6.3. Vitamin A and C

6.4. Vitamin A and Zinc

7. Comparing Vitamin A Requirements: Livestock vs. Pets

8. Future Directions and Research Gaps

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| 1,25(OH)2D3 | 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 |

| 11c-RAL | 11-cis-retinal; ADHs, alcohol dehydrogenases |

| ADHs | Alcohol dehydrogenases |

| ALDHs | Aldehyde dehydrogenases |

| APCs | Antigen-presenting cells |

| ATRA | All-trans retinoic acid |

| BCO1 | β,β-carotene-15,15-dioxygenase |

| CRABPs | Cellular retinoic acid-binding proteins |

| CRALBP | Cellular retinaldehyde-binding protein |

| CRBP | Intracellular retinol-binding protein |

| CRBP1 | Cellular retinol-binding protein 1 |

| CRBP2 | Cellular retinol-binding protein 2 |

| DBP | Vitamin D-binding protein |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| E2 | Estradiol |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| Ig | Immunoglobulin |

| ILCs | Innate lymphoid cells |

| IRFs | Interferon Regulatory Factors |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| LRAT | Lecithin:retinol acyltransferase |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| Pitx2 i | RA/RAR-regulated transcription factor |

| RA | All-trans-retinoic acid |

| RAL | All-trans-retinaldehyde |

| RALDHs | Retinaldehyde dehydrogenases |

| RAR | Retinoic acid receptors |

| RBP | Serum retinol-binding protein |

| REHs | Retinyl ester hydrolases |

| REs | Retinyl esters |

| RESs | Retinyl esterases |

| ROL | All-trans-retinol |

| RPE | Retinal pigment epithelium |

| RPE65 | Retinoid isomerase |

| RXR | Retinoid X receptors |

| SCARB1 | Scavenger receptor class B, type I |

| SDRs | Short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases |

| STRA6 | Retinoic acid 6 |

| Th | T helper cells |

| Treg | regulatory T cells |

| TTR | Transthyretin |

| VDR | Vitamin D receptor |

| VDRE | Vitamin D response element |

| VLDL | Very low-density lipoprotein |

| βC | β,β-carotene |

References

- Gordon, D.S.; Rudinsky, A.J.; Guillaumin, J.; Parker, V.J.; Creighton, K.J. Vitamin C in Health and Disease: A Companion Animal Focus. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2020, 39, 100432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockman, J.; Villaverde, C.; Corbee, R.J. Calcium, Phosphorus, and Vitamin D in Dogs and Cats: Beyond the Bones. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2021, 51, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Z.; Bian, Z.; Huang, H.; Liu, T.; Ren, R.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Deng, B.; Zhang, L. Dietary Strategies for Relieving Stress in Pet Dogs and Cats. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shastak, Y.; Gordillo, A.; Pelletier, W. The relationship between vitamin A status and oxidative stress in animal production. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2023, 51, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastak, Y.; Pelletier, W. The role of vitamin A in non-ruminant immunology. Front. Anim. Sci. 2023, 4, 1197802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, R.J. Liquid A Drops. Technical Report for Veterinarian Use Only. VBS Direct Ltd. 1 Mill View Close, Bulkeley, Cheshire, SY14 8DB. 2024. Available online: https://vbsdirect.co.uk/files/Vitamin_A_Tech_Report2.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Carazo, A.; Macáková, K.; Matoušová, K.; Krčmová, L.K.; Protti, M.; Mladěnka, P. Vitamin A Update: Forms, Sources, Kinetics, Detection, Function, Deficiency, Therapeutic Use and Toxicity. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoveller, A.K.; De Godoy, M.R.; Larsen, J.; Flickinger, E. Emerging Advancements in Canine and Feline Metabolism and Nutrition. Sci. World J. 2016, 2016, 9023781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, T.D. Diet and skin disease in dogs and cats. J. Nutr. 1998, 128 (Suppl. S12), 2783S–2789S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, P.J.; Salt, C.; Raila, J.; Brenten, T.; Kohn, B.; Schweigert, F.J.; Zentek, J. Safety evaluation of vitamin A in growing dogs. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 1800–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASEM (The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). Nutrient Requirements of Dogs and Cats; National Academy of Science: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Di Cerbo, A.; Morales-Medina, J.C.; Palmieri, B.; Pezzuto, F.; Cocco, R.; Flores, G.; Iannitti, T. Functional foods in pet nutrition: Focus on dogs and cats. Res. Vet. Sci. 2017, 112, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Oliva, A.; Mota-Rojas, D.; Semendric, I.; Whittaker, A.L. The Impact of Vegan Diets on Indicators of Health in Dogs and Cats: A Systematic Review. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, H.; Schor, S.M.; Murphy, B.D.; DeAngelis, B.; Feingold, S.; Frank, O. Blood vitamin and choline concentrations in healthy domestic cats, dogs, and horses. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1986, 47, 1468–1471. [Google Scholar]

- Green, A.S.; Fascetti, A.J. Meeting the vitamin A requirement: The efficacy and importance of β-carotene in animal species. Sci. World J. 2016, 2016, 7393620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbrugghe, A.; Dodd, S. Plant-Based Diets for Dogs and Cats. World Small Animal Veterinary Association Congress Proceedings. 2019. Available online: https://www.vin.com/doc/?id=9382843 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- McCollum, E.V.; Davis, M. The necessity of certain lipins in the diet during growth. J. Biol. Chem. 1913, 15, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellanby, E. Diet and disease, with special reference to the teeth, lungs, and pre-natal feeding. Lancet 1926, 1, 515–519. [Google Scholar]

- Stimson, A.M.; Hedley, O.F. Observations on Vitamin A Deficiency in Dogs. Public Health Rep. 1933, 48, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semba, R.D. Vitamin A as “anti-infective” therapy, 1920–1940. J. Nutr. 1999, 129, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitner, Z.A. The Clinical Significance Of Vitamin-A Deficiency. Br. Med. J. 1951, 1, 1110–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lanska, D.J. Chapter 29: Historical aspects of the major neurological vitamin deficiency disorders: Overview and fat-soluble vitamin A. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 95, pp. 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastak, Y.; Pelletier, W.; Kuntz, A. Insights into Analytical Precision: Understanding the Factors Influencing Accurate Vitamin A Determination in Various Samples. Analytica 2024, 5, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semba, R.D. On the ‘Discovery’ of Vitamin A. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 61, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. Isolation of Vitamin A. Nature 1932, 129, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, H.N.; Corbet, R.E. The Isolation of Crystalline Vitamin A1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1937, 59, 2042–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, P.P.; Greaves, J.P.; Scott, M.G. Nutritional blindness in the cat. Exp. Eye Res. 1964, 3, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASEM (The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). Nutrient Requirements of Dogs; National Academy of Science: Washington, DC, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- NASEM (The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). Nutrient Requirements of Cats; National Academy of Science: Washington, DC, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Case, L.P.; Daristotle, L.; Hayek, M.G.; Raasch, M.F. Pet Foods in: Canine and Feline Nutrition; Elsevier Inc.: Maryland Heights, MO, USA, 2011; pp. 119–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PFI (Pet Food Institute). 2023. Available online: https://www.petfoodinstitute.org/about-pet-food/nutrition/history-of-pet-food/ (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- NASEM (The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). Nutrient Requirements of Domestic Animals: Nutrient Requirement of Dog and Cats; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- NASEM (The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). Nutrient Requirements of Domestic Animals: Nutrient Requirement of Cats; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, S.A.S.; Shoveller, A.K.; Fascetti, A.J.; Yu, Z.Z.; Ma, D.W.L.; Verbrugghe, A. A Comparison of Key Essential Nutrients in Commercial Plant-Based Pet Foods Sold in Canada to American and European Canine and Feline Dietary Recommendations. Animals 2021, 11, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FEDIAF Scientific Advisory Board Nutritional Guidelines for Complete and Complementary Pet Food for Cats and Dogs. 2021. pp. 1–98. Available online: https://europeanpetfood.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Updated-Nutritional-Guidelines.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Kumar, N.; Gupta, R.C.; Nagarajan, G. Vitamin A deficiency in dogs: A review. J. Anim. Res. 2016, 6, 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Stasieniuk, E.; Barbi, L.; Bomcompagni, T. Recent Advances in Nutritional Immunomodulation in Dogs and Cats. All Pet Food. 2022. Available online: https://en.allpetfood.net/entrada/recent-advances-in-nutritional-immunomodulation-in-dogs-and-cats-53655 (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Lam, A.T.H.; Affolter, V.K.; Outerbridge, C.A.; Gericota, B.; White, S.D. Oral vitamin A as an adjunct treatment for canine sebaceous adenitis. Vet. Dermatol. 2011, 22, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Qi, G.; Brand, D.; Zheng, S.G. Role of Vitamin A in the Immune System. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.M.; Teixeira, F.M.E.; Sato, M.N. Impact of Retinoic Acid on Immune Cells and Inflammatory Diseases. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018, 2018, 3067126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roche, F.C.; Harris-Tryon, T.A. Illuminating the Role of Vitamin A in Skin Innate Immunity and the Skin Microbiome: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bennekum, A.M.; Fisher, E.A.; Blaner, W.S.; Harrison, E.H. Hydrolysis of retinyl esters by pancreatic triglyceride lipase. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 4900–4906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynd, P.I. Digestion in the mono-gastric animal. In Animal Nutrition: From Theory to Practice; Hynd, P.I., Ed.; CSIRO Publishing: Clayton South, VIC, Australia, 2019; pp. 42–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kaser, M.M.; Hussey, C.V.; Ellis, S.J. The Absorption of Vitamin A in Dogs Following Cholecystonephrostomy. J. Nutr. 1958, 66, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouti, V.; Papazoglou, L.; Rallis, T. Short-Bowel Syndrome in Dogs and Cats. Compend. Contin. Educ. Pract. Vet. 2006, 28, 182–193. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D.E.; Hejazi, J.; Elstad, N.L.; Ing-Fong, C.; Gleeson, J.M.; Iverius, P.-H. Novel aspects of vitamin A metabolism in the dog: Distribution of lipoprotein retinyl esters in vitamin A-deprived and cholesterol-fed animals. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1987, 922, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelstowska, S.; Widjaja-Adhi, M.A.; Silvaroli, J.A.; Golczak, M. Molecular Basis for Vitamin A Uptake and Storage in Vertebrates. Nutrients 2016, 8, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seawright, A.A.; English, P.B.; Gartner, R.J.W. Hypervitaminosis A and deforming cervical spondylosis of the cat. J. Comp. Pathol. 1967, 77, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, R.; Barrena, S.; Muñoz-Chápuli, R. Retinoids in Stellate Cells: Development, Repair, and Regeneration. J. Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, B.P.; Park, J.S.; Wong, T.S.; Weng, B.C.; Kim, H.W.; Byrne, K.M.; Hayek, M.G.; Reinhart, G.A. Role of dietary β-carotene in modulating cell-mediated and humoral immune responses in dogs. FASEB J. 1998, 12, A967. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, B.P.; Park, J.S.; Weng, B.C.; Wong, T.S.; Hayek, M.G.; Reinhart, G.A. Dietary β-carotene is taken up by blood plasma and leukocytes in dogs. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1788–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gershoff, S.N.; Andrus, S.B.; Hegsted, D.M.; Lentini, E.A. Vitamin A deficiency in cats. Lab. Investig. 1957, 6, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakshmanan, M.R.; Chansang, H.; Olson, J.A. Purification and properties of carotene 15, 15′-dioxygenase of rabbit intestine. J. Lipid Res. 1972, 13, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweigert, F.J.; Raila, J.; Wichert, B.; Kienzle, E. Cats absorb beta-carotene, but it is not converted to vitamin A. J. Nutr. 2002, 132 (Suppl. S2), 1610S–1612S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, B.P.; Park, J.S. Carotenoid action on the immune response. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 257S–261S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.S.; Tang, G.; Lango, J.; Klasing, K.C.; Fascetti, A.J. Domestic cats convert [2H8]-β-carotene to [2H4]-retinol following a single oral dose. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2012, 96, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, H.B., III; Merrill, A.H., Jr. Riboflavin-Binding Proteins. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1988, 8, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M’Clelland, D.A. The Refolding of Riboflavin Binding Protein. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Stirling, Stirling, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- van Hoek, I.; Meyer, E.; Duchateau, L.; Peremans, K.; Smets, P.; Daminet, S. Retinol-binding protein in serum and urine of hyperthyroid cats before and after treatment with radioiodine. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2009, 23, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raila, J.; Brunnberg, L.; Schweigert, F.J.; Kohn, B. Influence of kidney function on urinary excretion of albumin and retinol-binding protein in dogs with naturally occurring renal disease. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2010, 71, 1387–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinhoff, J.S.; Lass, A.; Schupp, M. Retinoid homeostasis and beyond: How retinol binding protein 4 contributes to health and disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shastak, Y.; Pelletier, W. Vitamin A supply in swine production: A review of current science and practical considerations. Appl. Anim. Sci. 2023, 39, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweigert, F.J.; Ryder, O.A.; Rambeck, W.A.; Zucker, H. The majority of vitamin A is transported as retinyl esters in the blood of most carnivores. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Comp. Physiol. 1990, 95, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raila, J.; Buchholz, I.; Aupperle, H.; Raila, G.; Schoon, H.A.; Schweigert, F.J. The distribution of vitamin A and retinol-binding protein in the blood plasma, urine, liver and kidneys of carnivores. Vet. Res. 2000, 31, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barko, P.C.; Williams, D.A. Serum concentrations of lipid-soluble vitamins in dogs with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency treated with pancreatic enzymes. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2018, 32, 1600–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raila, J.; Mathews, U.; Schweigert, F.J. Plasma transport and tissue distribution of beta-carotene, vitamin A and retinol-binding protein in domestic cats. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2001, 130, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, E.; Seehawer, J. Verwertung, Stoffwechsel, Bedeutung und Anwendung des Vitamins A bei Hund und Katze. Prakt. Tierarzt 2001, 82, 98–106. Available online: https://sd9915b4744868808.jimcontent.com/download/version/1478279129/module/10685394693/name/Vitamin%20A%20bei%20Hund%20und%20Katze.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Kolb, E. Vitamin A. In Verwertung und Anwendung von Vitaminen bei Haustieren; Hoffmann-LaRoche AG: Grenzach-Wyhlen, Germany, 1998; pp. 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Schweigert, F.J. Insensitivity of dogs to the effects of nonspecific bound vitamin A in plasma. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 1988, 58, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Raila, J.; Radon, R.; Trüpschuch, A.; Schweigert, F.J. Retinol and retinyl ester responses in the blood plasma and urine of dogs after a single oral dose of vitamin A. J. Nutr. 2002, 132 (Suppl. S2), 1673S–1675S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowe, H.D.; Lawler, D.F.; Kealy, R.D. Antioxidant status of pair-fed labrador retrievers is affected by diet restriction and aging. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1844–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puls, R. Vitamin Levels in Animal Health. Diagnostic Data; Sherpa International: Clearbrook, BC, Canada, 1994; p. 184. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, K.; Suri, D.J.; Davis, C.; Sheftel, J.; Nishimoto, K.; Yamaoka, Y.; Toya, Y.; Welham, N.V.; Tanumihardjo, S.A. Serum retinyl esters are positively correlated with analyzed total liver vitamin A reserves collected from US adults at time of death. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Byrne, S.M.; Blaner, W.S. Retinol and retinyl esters: Biochemistry and physiology. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 1731–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penniston, K.L.; Weng, N.; Binkley, N.; Tanumihardjo, S.A. Serum retinyl esters are not elevated in postmenopausal women with and without osteoporosis whose preformed vitamin A intakes are high. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chytil, F.; Ong, D.E. Cellular retinoid-binding proteins In The Retinoids; Sporn, M.B., Roberts, A.B., Goodman, D.S., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1984; Volume 2, pp. 89–123. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, N.; Ishibashi, M.; Soeta, S. Molecular characterization and tissue distribution of feline retinol-binding protein 4. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2013, 75, 1383–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Napoli, J.L. Functions of Intracellular Retinoid Binding-Proteins. Subcell. Biochem. 2016, 81, 21–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, R.; Horton, G.; Einaugler, R. Retinal Vessel Dehydrogenase Enzymes. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1964, 72, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, I.; Ang, H.L.; Duester, G. Alcohol dehydrogenases in Xenopus development: Conserved expression of ADH1 and ADH4 in epithelial retinoid target tissues. Dev. Dyn. 1998, 213, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connally, H.E.; Hamar, D.W.; Thrall, M.A. Inhibition of canine and feline alcohol dehydrogenase activity by fomepizole. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2000, 61, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sandell, L.L.; Trainor, P.A.; Koentgen, F.; Duester, G. Alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenases: Retinoid metabolic effects in mouse knockout models. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1821, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bchini, R.; Vasiliou, V.; Branlant, G.; Talfournier, F.; Rahuel-Clermont, S. Retinoic acid biosynthesis catalyzed by retinal dehydrogenases relies on a rate-limiting conformational transition associated with substrate recognition. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2013, 202, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedishvili, N.Y. Enzymology of retinoic acid biosynthesis and degradation. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 1744–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujihara, M.; Yamamizu, K.; Comizzoli, P.; Wildt, D.E.; Songsasen, N. Retinoic acid promotes in vitro follicle activation in the cat ovary by regulating expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9. PLoS ONE. 2018, 13, e0202759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Adin, C.; Shen, Q.; Lee, L.J.; Yu, L.; Fadda, P.; Samogyi, A.; Ham, K.; Xu, L.; Gilor, C.; et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 a1 regulates energy metabolism in adipocytes from different species. Xenotransplantation 2017, 24, e12318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, A.R.; Le, A.T.; Mather, T.; Burgett, A.; Berry, W.; Summers, J.A. Design, synthesis, and ex vivo evaluation of a selective inhibitor for retinaldehyde dehydrogenase enzymes. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 5766–5779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.; Lee, S.-M.; Heo, J.; Kwon, Y.M.; Chung, D.; Yu, W.-J.; Bae, S.S.; Choi, G.; Lee, D.-S.; Kim, Y. Retinaldehyde Dehydrogenase Inhibition-Related Adverse Outcome Pathway: Potential Risk of Retinoic Acid Synthesis Inhibition during Embryogenesis. Toxins 2021, 13, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasimanickam, V.R. Expression of retinoic acid-metabolizing enzymes, ALDH1A1, ALDH1A2, ALDH1A3, CYP26A1, CYP26B1 and CYP26C1 in canine testis during post-natal development. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2016, 51, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, J.E.; Blomhoff, R. Gene expression regulation by retinoic acid. J. Lipid Res. 2002, 43, 1773–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandebourg, T.D.; Hu, C.Y. Regulation of differentiating pig preadipocytes by retinoic acid. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 83, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mello Souza, C.H.; Valli, V.E.; Kitchell, B.E. Detection of retinoid receptors in non-neoplastic canine lymph nodes and in lymphoma. Can. Vet. J. 2014, 55, 1219–1224. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, B.; Lehmann, J.M.; Zhang, X.K.; Hermann, T.; Husmann, M.; Graupner, G.; Pfahl, M. A retinoic acid receptor-specific element controls the retinoic acid receptor-beta promoter. Mol. Endocrinol. 1990, 4, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastinejad, F.; Wagner, T.; Zhao, Q.; Khorasanizadeh, S. Structure of the RXR-RAR DNA-binding complex on the retinoic acid response element DR1. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 1045–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Chandra, V.; Rastinejad, F. Retinoic acid actions through mammalian nuclear receptors. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, G. The visual cycle of the cone photoreceptors of the retina. Nutr. Rev. 2004, 62 Pt 1, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.S.; Kefalov, V.J. The cone-specific visual cycle. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2011, 30, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byosiere, S.E.; Chouinard, P.A.; Howell, T.J.; Bennett, P.C. What do dogs (Canis familiaris) see? A review of vision in dogs and implications for cognition research. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2018, 25, 1798–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, C.M.; Jacobson, S.G.; Borruat, F.X.; Chaitin, M.H. Rhodopsin levels and retinal function in cats during recovery from vitamin A deficiency. Exp. Eye Res. 1989, 49, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazono, S.; Isayama, T.; Delori, F.C.; Makino, C.L. Vitamin A activates rhodopsin and sensitizes it to ultraviolet light. Vis. Neurosci. 2011, 28, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palczewski, K. Chemistry and biology of the initial steps in vision: The Friedenwald lecture. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 6651–6672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clagett-Dame, M.; Knutson, D. Vitamin A in Reproduction and Development. Nutrients 2011, 3, 385–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, M.; Goletz, P.W.; Crouch, R.K. 11-cis- and all-trans-retinols can activate rod opsin: Rational design of the visual cycle. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 7567–7571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiser, P.D. Retinal pigment epithelium 65 kDa protein (RPE65): An update. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2022, 88, 101013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stecher, H.; Gelb, M.H.; Saari, J.C.; Palczewski, K. Preferential release of 11-cis-retinol from retinal pigment epithelial cells in the presence of cellular retinaldehyde-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 8577–8585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R.O.; Crouch, R.K. Retinol dehydrogenases (RDHs) in the visual cycle. Exp. Eye Res. 2010, 91, 788–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, O. The retinal pigment epithelium in visual function. Physiol. Rev. 2005, 85, 845–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daruwalla, A.; Choi, E.H.; Palczewski, K.; Kiser, P.D. Structural biology of 11-cis-retinaldehyde production in the classical visual cycle. Biochem. J. 2018, 475, 3171–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palczewski, K.; Kiser, P.D. Shedding new light on the generation of the visual chromophore. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 19629–19638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastak, Y.; Pelletier, W. Nutritional Balance Matters: Assessing the Ramifications of Vitamin A Deficiency on Poultry Health and Productivity. Poultry 2023, 2, 493–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, H.D.; Collins, G.; Pyle, R.; Key, M.; Taub, D.D. The Retinoic Acid Receptor-alpha mediates human T-cell activation and Th2 cytokine and chemokine production. BMC Immunol. 2008, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, J.R.; Iwata, M.; von Andrian, U.H. Vitamin effects on the immune system: Vitamins A and D take centre stage. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matikainen, S.; Ronni, T.; Hurme, M.; Pine, R.; Julkunen, I. Retinoic acid activates interferon regulatory factor-1 gene expression in myeloid cells. Blood 1996, 88, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Tanoury, Z.; Piskunov, A.; Rochette-Egly, C. Vitamin A and retinoid signaling: Genomic and nongenomic effects. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 1761–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, X.; Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, B.; Liang, W.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, P.; Li, S. Molecular characterization and antiviral effects of canine interferon regulatory factor 1 (CaIRF1). BMC Vet. Res. 2022, 18, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Kang, H.; Hu, X.; Liu, J.; Tian, J.; Qu, L. Identification of Feline Interferon Regulatory Factor 1 as an Efficient Antiviral Factor against the Replication of Feline Calicivirus and Other Feline Viruses. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 2739830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferies, C.A. Regulating IRFs in IFN Driven Disease. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourkochristou, E.; Triantos, C.; Mouzaki, A. The Influence of Nutritional Factors on Immunological Outcomes. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 665968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, H.N.; Mellanby, E. Vitamin A as an anti-infective agent. Brit. Med. J. 1928, 2, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bono, M.R.; Tejon, G.; Flores-Santibañez, F.; Fernandez, D.; Rosemblatt, M.; Sauma, D. Retinoic Acid as a Modulator of T Cell Immunity. Nutrients 2016, 8, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villamor, E.; Fawzi, W. Effects of Vitamin A supplementation on immune responses and correlation with clinical outcomes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 18, 446–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gürbüz, M.; Aktaç, S. Understanding the role of Vitamin A and its precursors in the immune system. Nutr. Clin. Metab. 2022, 36, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephensen, C.B. Vitamin A, infection, and immune function. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2001, 21, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, H.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Z. Effects of starch and gelatin encapsulated Vitamin A on growth performance, immune status and antioxidant capacity in weaned piglets. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 6, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, S.A.; McCaffery, P.Y.; Drager, U.C.; de Luca, L.M. Retinoids in embryonal development. Physiol. Rev. 2000, 80, 1021–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, R.K.; Deng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, H. Retinoic acid synthesis and functions in early embryonic development. Cell Biosci. 2012, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, V.; Rochette-Egly, C. The molecular physiology of nuclear retinoic acid receptors. From health to disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1812, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.; Rose, R.E.; Jones, D.R.; Saint-Jeannet, J.P. Generating retinoic acid gradients by local degradation during craniofacial development: One cell’s cue is another cell’s poison. Genesis 2018, 56, e23091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G. Retinoic acid receptor regulation of decision-making for cell differentiation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1182204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duester, G. Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis. Cell 2008, 134, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.; Nordling, S.; Vasavada, H.H.; Butcher, E.C.; Hirschi, K.K. Retinoic Acid Promotes Endothelial Cell Cycle Early G1 State to Enable Human Hemogenic Endothelial Cell Specification. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Detailed Review Paper on the Retinoid System. OECD Series on Testing and Assessment, Nr.343, Paris. 2021. Available online: https://one.oecd.org/document/ENV/CBC/MONO(2021)20/en/pdf (accessed on 11 February 2024).

- Gross, K.L.; Wedekind, K.J.; Kirk, C.A.; Cowell, C.S.; Schoenherr, W.D.; Richardson, D.C. Effect of dietary vitamin A on reproductive performance and immune response of dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1990, 51, 1423–1430. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, A.H.; Power, H.T. Retinoids in veterinary dermatology. Clin. Dermatol. 1994, 12, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauli, S.A.; Session, D.R.; Shang, W.; Easley, K.; Wieser, F.; Taylor, R.N.; Pierzchalski, K.; Napoli, J.L.; Kane, M.A.; Sidell, N. Analysis of follicular fluid retinoids in women undergoing in vitro fertilization: Retinoic acid influences embryo quality and is reduced in women with endometriosis. Reprod. Sci. 2013, 20, 1116–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demczuk, M.; Huang, H.; White, C.; Kipp, J.L. Retinoic acid regulates calcium signaling to promote mouse ovarian granulosa cell proliferation. Biol. Reprod. 2016, 95, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwa, H.; Kishi, H.; Imai, F.; Nakao, K.; Hirakawa, T.; Minegishi, T. Retinoic acid enhances progesterone production via the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway in immature rat granulosa cells. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2016, 8, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, L.; Wang, F.; Zhou, X. Potential role of retinoids in ovarian physiology and pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin. Chim. Acta 2017, 469, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munetsuna, E.; Hojo, Y.; Hattori, M.; Ishii, H.; Kawato, S.; Ishida, A.; Kominami, S.A.; Yamazaki, T. Retinoic acid stimulates 17β-estradiol and testosterone synthesis in rat hippocampal slice cultures. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 4260–4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damdimopoulou, P.; Chiang, C.; Flaws, J.A. Retinoic acid signaling in ovarian folliculogenesis and steroidogenesis. Reprod. Toxicol. 2019, 87, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.C.; Xia, H.F.; Sun, J.; Yang, Y.; Peng, J.P. Retinoic acid-metabolizing enzyme cytochrome P450 26a1 (cyp26a1) is essential for implantation: Functional study of its role in early pregnancy. J. Cell. Physiol. 2010, 223, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Haller, M.E.; Chadchan, S.B.; Kommagani, R.; Ma, L. Signaling through retinoic acid receptors is essential for mammalian uterine receptivity and decidualization. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e150254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, D.; Assis, L.H.C.; van de Kant, H.J.G.; de Waard, S.; Safian, D.; Lemos, M.S.; Bogerd, J.; Schulz, R.W. Endocrine and local signaling interact to regulate spermatogenesis in zebrafish: Follicle-stimulating hormone, retinoic acid and androgens. Development 2019, 146, dev178665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griswold, M.D. Cellular and molecular basis for the action of retinoic acid in spermatogenesis. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2022, 69, T51–T57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewell, D.E.; Toll, P.W.; Wedekind, K.J.; Zicker, S.C. Effect of increasing dietary antioxidants on concentrations of vitamin E and total alkenals in serum of dogs and cats. Vet. Ther. 2000, 1, 264–272. [Google Scholar]

- Espadas, I.; Ricci, E.; McConnell, F.; Sanchez-Masian, D. MRI, CT and histopathological findings in a cat with hypovitaminosis A. Vet. Rec. Case Rep. 2017, 5, e000467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landete, J.M. Dietary intake of natural antioxidants: Vitamins and polyphenols. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 706–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krinsky, N.I.; Johnson, E.J. Carotenoid actions and their relation to health and disease. Mol. Asp. Med. 2005, 26, 459–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dao, D.Q.; Ngo, T.C.; Thong, N.M.; Nam, P.C. Is vitamin A an antioxidant or a pro-oxidant? J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 121, 9348–9357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palace, V.P.; Khaper, N.; Qin, Q.; Singal, P.K. Antioxidant potentials of vitamin A and carotenoids and their relevance to heart disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 746–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaner, W.S.; Shmarakov, I.O.; Traber, M.G. Vitamin A and vitamin E: Will the real antioxidant please stand up? Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2021, 41, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, U.-H.; Han, H.S.; Um, E.; An, X.-H.; Kim, E.-J.; Um, S.J. Redox regulation of transcriptional activity of retinoic acid receptor by thioredoxin glutathione reductase (TGR). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 390, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Haddad, M.; Jean, E.; Turki, A.; Hugon, G.; Vernus, B.; Bonnieu, A.; Passerieux, E.; Hamade, A.; Mercier, J.; Laoudj-Chenivesse, D.; et al. Glutathione peroxidase 3, a new retinoid target gene, is crucial for human skeletal muscle precursor cell survival. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 6147–6156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brigelius-Flohé, R.; Flohé, L. Regulatory phenomena in the glutathione peroxidase superfamily. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2020, 33, 498–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, P.; Lu, L.; Zhang, F. All-trans retinoic acid alleviates hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury by enhancing manganese superoxide dismutase in rats. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2010, 33, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, M.M.; Hussein, A.M.; Marghani, B.H.; Barakat, N.M.; Khedr, M.M.M.; Heakel, N.A. Retinoic acid potentiates the therapeutic efficiency of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) against cisplatin-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Sci. Pharm. 2022, 90, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

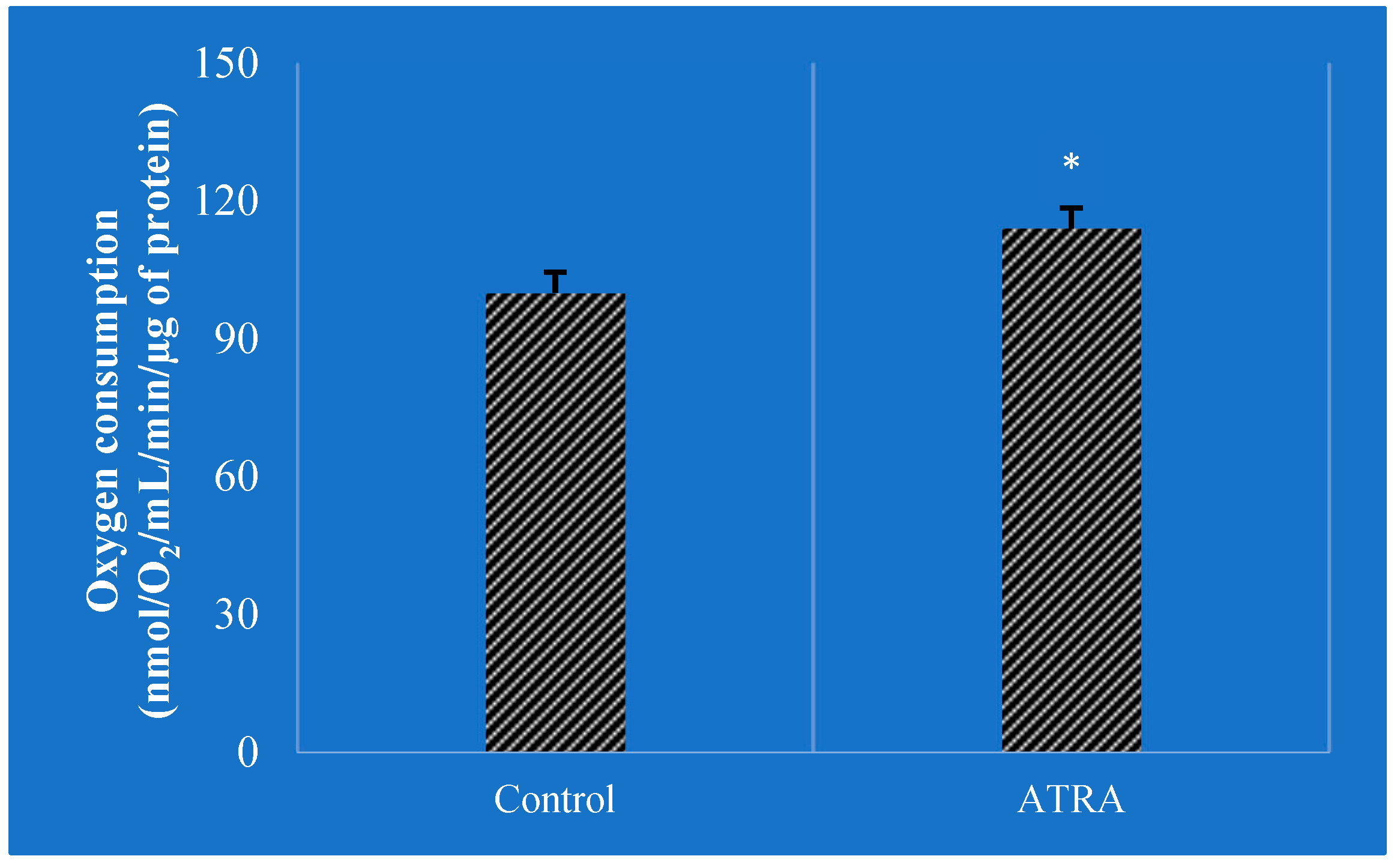

- Tourniaire, F.; Musinovic, H.; Gouranton, E.; Astier, J.; Marcotorchino, J.; Arreguin, A.; Bernot, D.; Palou, A.; Bonet, M.L.; Ribot, J.; et al. All-trans retinoic acid induces oxidative phosphorylation and mitochondria biogenesis in adipocytes. J. Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 1100–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, S.; Chapman, J.D.; Han, C.Y.; Hogarth, C.A.; Arnold, S.L.; Onken, J.; Kent, T.; Goodlett, D.R.; Isoherranen, N. All-trans-retinoic acid enhances mitochondrial function in models of human liver. Mol. Pharmacol. 2016, 89, 560–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajawat, Y.; Hilioti, Z.; Bossis, I. Autophagy: A target for retinoic acids. Autophagy 2010, 6, 1224–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, A.M.; Ryter, S.W.; Levine, B. Autophagy in human health and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1845–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polizopoulou, Z.S.; Kazakos, G.; Patsikas, M.N.; Roubies, N. Hypervitaminosis A in the cat: A case report and review of the literature. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2005, 7, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, J.M.; Daniel, A.G.; Aloia, T.P.; de Siqueira, A.; Fukushima, A.R.; Simões, D.M.N.; Reche-Júior, A.; Cogliati, B. Hypervitaminosis A-induced hepatic fibrosis in a cat. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 2014, 16, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralli, E.P.; Pariente, A.; Flaum, G.; Waterhouse, A. A study of vitamin A deficiency in normal and depancreatized dogs. Am. J. Physiol.-Leg. Content 1933, 103, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crimm, P.D.; Short, D.M. Vitamin a deficiency in the dog. Am. J. Physiol.-Leg. Content 1937, 118, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennogle, S.A.; Priestnall, S.L.; Suárez-Bonnet, A.; Webb, C.B. Comparison of clinical, clinicopathologic, and histologic variables in dogs with chronic inflammatory enteropathy and low or normal serum 25-hydroxycholecalciferol concentrations. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2019, 33, 1995–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olcott, H.S. Vitamin A Deficiency in the Dog. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1933, 30, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihrke, P.J.; Goldschmidt, M.H. Vitamin A-responsive dermatosis in the dog. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1983, 182, 687–690. [Google Scholar]

- Verstegen, J.; Dhaliwal, G.; Verstegen-Onclin, K. Canine and feline pregnancy loss due to viral and non-infectious causes: A review. Theriogenology 2008, 70, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, J. Factors affecting vitamin A transport in animals and man. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1983, 42, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, J.A. Serum levels of vitamin A and carotenoids as reflectors of nutritional status. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1984, 73, 1439–1444. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schweigert, F.J.; Thomann, E.; Zucker, H. Vitamin A in the urine of carnivores. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 1991, 61, 110–113. [Google Scholar]

- Faure, H.; Preziosi, P.; Roussel, A.M.; Bertrais, S.; Galan, P.; Hercberg, S.; Favier, A. Factors influencing blood concentration of retinol, α-tocopherol, vitamin C, and β-carotene in the French participants of the SU.VI.MAX trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 60, 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, A.; Harrison, E. Vitamin A: Nutritional aspects of retinoids and carotenoids. In Handbook of Vitamins, 4th ed.; Zempleni, J., Rucker, R.B., Suttie, J.W., McCormick, D.B., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Shastak, Y.; Witzig, M.; Hartung, K.; Bessei, W.; Rodehutscord, M. Comparison and evaluation of bone measurements for the assessment of mineral phosphorus sources in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2012, 91, 2210–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastak, Y.; Rodehutscord, M. Determination and estimation of phosphorus availability in growing poultry and their historical development. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2013, 69, 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Weinstein, S.J.; Yu, K.; Männistö, S.; Albanes, D. Association between serum retinol and overall and cause-specific mortality in a 30-year prospective cohort study. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fascetti, A.J. Nutritional management and disease prevention in healthy dogs and cats. R. Bras. Zootec. 2010, 39, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cline, M.G.; Burns, K.M.; Coe, J.B.; Downing, R.; Durzi, T.; Murphy, M.; Parker, V. 2021 AAHA Nutrition and Weight Management Guidelines for Dogs and Cats. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2021, 57, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L. Hypervitaminosis A: A review. Aust. Vet. J. 1971, 47, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, E. Vitamin A. In Der Gehalt an Vitaminen im Blut, im Blutplasma, in Geweben und in der Milch von Haustieren: Bedeutung für Gesundheit und Diagnostik; Hoffmann-La Roche AG: Grenzach-Wyhlen, Germany, 1999; pp. 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for vitamin A. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seawright, A.A.; Hrdlicka, J. Pathogenetic factors in tooth loss in young cats on a high daily oral intake of vitamin A. Aust. Vet. J. 1974, 50, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NASEM (The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). Vitamin Tolerance of Animals; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- AAFCO (Association of American Feed Control Officials). 2014. AAFCO Dog and Cat Food Nutrient Profiles, Champaign, Illinois, USA. Available online: https://www.aafco.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Model_Bills_and_Regulations_Agenda_Midyear_2015_Final_Attachment_A.__Proposed_revisions_to_AAFCO_Nutrient_Profiles_PFC_Final_070214.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Zafalon, R.V.A.; Ruberti, B.; Rentas, M.F.; Amaral, A.R.; Vendramini, T.H.A.; Chacar, F.C.; Kogika, M.M.; Brunetto, M.A. The Role of Vitamin D in Small Animal Bone Metabolism. Metabolites 2020, 10, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Džopalić, T.; Božić-Nedeljković, B.; Jurišić, V. The role of vitamin A and vitamin D in modulation of the immune response with a focus on innate lymphoid cells. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2021, 46, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilland, J.-C. Les interactions entre les vitamines A, D, E et K: Synergie et/ou competition. OCL 2011, 18, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, P.N.; Dowd, D.R.; Nakajima, S.; Galligan, M.A.; Reeder, M.C.; Haussler, C.A.; Ozato, K.; Haussler, M.R. Retinoid X receptors stimulate and 9-cis retinoic acid inhibits 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-activated expression of the rat osteocalcin gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993, 13, 5907–5917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiter, B.; Patil, S.U.; Shreffler, W.G. Vitamins A and D have antagonistic effects on expression of effector cytokines and gut-homing integrin in human innate lymphoid cells. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2015, 45, 1214–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Chiang, E.P.; Syu, J.N.; Chao, C.Y.; Lin, H.Y.; Lin, C.C.; Yang, M.D.; Tsai, S.Y.; Tang, F.Y. Treatment of 13-cis retinoic acid and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits TNF-alpha-mediated expression of MMP-9 protein and cell invasion through the suppression of JNK pathway and microRNA 221 in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treptow, S.; Grün, J.; Scholz, J.; Radbruch, A.; Heine, G.; Worm, M. 9-cis Retinoic acid and 1.25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 drive differentiation into IgA+ secreting plasmablasts in human naïve B cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2021, 51, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastak, Y.; Obermueller-Jevic, U.; Pelletier, W. A Century of Vitamin E: Early Milestones and Future Directions in Animal Nutrition. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesoriere, L.; Bongiorno, A.; Pintaudi, A.M.; D’Anna, R.; D’Arpa, D.; Livrea, M.A. Synergistic interactions between vitamin A and vitamin E against lipid peroxidation in phosphatidylcholine liposomes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996, 326, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesoriere, L.; Ciaccio, M.; Bongiorno, A.; Riccio, A.; Pintaudi, A.M.; Livrea, M.A. Antioxidant activity of all-trans-retinol in homogeneous solution and in phosphatidylcholine liposomes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1993, 307, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Tullio, M.C. The Mystery of Vitamin C. Nat. Educ. 2010, 3, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Kanter, M.; Coskun, O.; Armutcu, F.; Uz, Y.H.; Kizilay, G. Protective effects of vitamin C, alone or in combination with vitamin A, on endotoxin-induced oxidative renal tissue damage in rats. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2005, 206, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini Omshi, F.S.; Abbasalipourkabir, R.; Abbasalipourkabir, M.; Nabyan, S.; Bashiri, A.; Ghafourikhosroshahi, A. Effect of vitamin A and vitamin C on attenuation of ivermectin-induced toxicity in male Wistar rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 29408–29417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.H.; Sermersheim, M.; Li, H.; Lee, P.H.U.; Steinberg, S.M.; Ma, J. Zinc in Wound Healing Modulation. Nutrients 2017, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Wahed, M.A.; Fuchs, G.J.; Baqui, A.H.; Alvarez, J.O. Synergistic Effect of Zinc and Vitamin A on the Biochemical Indexes of Vitamin A Nutrition in Children. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 75, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, F.M.O.; Santos, M.O.; Venturin, G.L.; Bragato, J.P.; Rebech, G.T.; Melo, L.M.; Costa, S.F.; de Freitas, J.H.; Siqueira, C.E.; Morais, D.A.; et al. Vitamins A and D and Zinc Affect the Leshmanicidal Activity of Canine Spleen Leukocytes. Animals 2021, 11, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.; Kolba, N.; Tako, E. Assessing the Interactions between Zinc and Vitamin A on Intestinal Functionality, Morphology, and the Microbiome In Vivo (Gallus gallus). Nutrients 2023, 15, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, K.Z.; Rosado, J.L.; Montoya, Y.; Solano, M.D.L.; Hertzmark, E.; DuPont, H.L.; Santos, J.I. Effect of Vitamin A and Zinc Supplementation on Gastrointestinal Parasitic Infections among Mexican Children. Pediatrics 2007, 120, e846–e855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.C., Jr. The vitamin A-zinc connection: A review. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1980, 355, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, P.; West, K.P., Jr. Interactions between zinc and vitamin A: An update. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 68 (Suppl. S2), 435S–441S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.; Koo, S.I. Effects of zinc and essetial fatty acid deficiencies on the lymphatic absorption of vitamin A and secretion of phospholipids. J. Nutr. Biochem. 1995, 6, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastak, Y.; Pelletier, W. Balancing Vitamin A Supply for Cattle: A Review of the Current Knowledge. In Advances in Animal Science and Zoology 21; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2023; Chapter 2; Available online: https://novapublishers.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Advances-in-Animal-Science-and-Zoology.-Volume-21-Chapter-2.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Shastak, Y.; Pelletier, W. Delving into Vitamin A Supplementation in Poultry Nutrition: Current Knowledge, Functional Effects, and Practical Implications. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 2023, 80, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearin, A.L.; Ostrander, E.A. Canine morphology: Hunting for genes and tracking mutations. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streitberger, K.; Schweizer, M.; Kropatsch, R.; Dekomien, G.; Distl, O.; Fischer, M.S.; Epplen, J.T.; Hertwig, S.T. Rapid genetic diversification within dog breeds as evidenced by a case study on Schnauzers. Anim. Genet. 2012, 43, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finka, L.R.; Luna, S.P.L.; Mills, D.S.; Farnworth, M.J. The Application of Geometric Morphometrics to Explore Potential Impacts of Anthropocentric Selection on Animals’ Ability to Communicate via the Face: The Domestic Cat as a Case Study. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 606848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, J.; Talenti, A.; Arvelius, P.; Strandberg, E.; Haskell, M.J.; Wiener, P. Unravelling selection signatures in a single dog breed suggests recent selection for morphological and behavioral traits. Adv. Genet. 2020, 1, e10024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauridsen, M. Vitamin E—A Key Nutritional Factor for Health and Growth; VII Latin American Animal Nutrition Congress—CLANA: Cancun, Mexico, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sacakli, P.; Ramay, M.S.; Harijaona, J.A.; Shastak, Y.; Pelletier, W.; Gordillo, A.; Calik, A. 2024. Does the latest NASEM vitamin A requirement estimate support optimal growth in broiler chickens? In Proceedings of the 16th European Poultry Congress, Valencia, Spain, 24–28 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Williams, F.J.; Dreger, D.L.; Plassais, J.; Davis, B.W.; Parker, H.G.; Ostrander, E.A. Genetic selection of athletic success in sport-hunting dogs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E7212–E7221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H.; Heckötter, E. Futterwerttabellen für Hunde und Katzen; Schlüter: Hannover, Germany, 1986; pp. 9–12. ISBN 3877060854. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, L.R. (Ed.) Vitamin A. In Vitamins in Animal and Human Nutrition; Iowa State University Press: Ames, IA, USA, 2000; pp. 5–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, L.R. (Ed.) Vitamin Supplementation. In Vitamins in Animal Nutrition: Comparative Aspects to Human Nutrition, 1st ed.; Academic Press Inc.: Iowa, IA, USA, 1989; pp. 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kırkpınar, F.; Açıkgöz, Z. Feeding. In Animal Husbandry and Nutrition; Yücel, B., Taşkin, T., Eds.; IntechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2018; pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AWT (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Wirkstoffe in der Tierernährung e.V.). Vitamins in Animal Nutrition: Vitamin E; AgriMedia: Eisenberg, Germany, 2002; p. 50. ISBN 3-86037-167-3. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Shrestha, N.; Préat, V.; Beloqui, A. An overview of in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo models for studying the transport of drugs across intestinal barriers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 175, 113795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.J. The use of animal models in diabetes research. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 166, 877–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, C.A.; Hanna-Rose, W. Animal Model Contributions to Congenital Metabolic Disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1236, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campion, S.; Inselman, A.; Hayes, B.; Casiraghi, C.; Joseph, D.; Facchinetti, F.; Salomone, F.; Schmitt, G.; Hui, J.; Davis-Bruno, K.; et al. The benefits, limitations and opportunities of preclinical models for neonatal drug development. Dis. Model. Mech. 2022, 15, dmm049065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borel, P.; Desmarchelier, C. Genetic Variations Associated with Vitamin A Status and Vitamin A Bioavailability. Nutrients 2017, 9, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, M.; Tomita, M. Genetic Variations of Vitamin A-Absorption and Storage-Related Genes, and Their Potential Contribution to Vitamin A Deficiency Risks Among Different Ethnic Groups. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 861619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanumihardjo, S.A. Vitamin A: Biomarkers of nutrition for development. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 658S–665S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanumihardjo, S.A.; Russell, R.M.; Stephensen, C.B.; Gannon, B.M.; Craft, N.E.; Haskell, M.J.; Lietz, G.; Schulze, K.; Raiten, D.J. Biomarkers of Nutrition for Development (BOND)-Vitamin A Review. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 1816S–1848S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amimo, J.O.; Michael, H.; Chepngeno, J.; Raev, S.A.; Saif, L.J.; Vlasova, A.N. Immune Impairment Associated with Vitamin A Deficiency: Insights from Clinical Studies and Animal Model Research. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carratù, M.R.; Marasco, C.; Mangialardi, G.; Vacca, A. Retinoids: Novel immunomodulators and tumour-suppressive agents? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 167, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, A.; van Egmond, M.; Mebius, R. The role of retinoic acid in the production of immunoglobulin A. Mucosal Immunol. 2022, 15, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, C.; Waly, N. Mucosal defence along the gastrointestinal tract of cats and dogs. Vet. Res. 2006, 37, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Allenspach, K. Clinical immunology and immunopathology of the canine and feline intestine. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2011, 41, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen-Jones, S.M.; Komáromy, A.M. Canine and Feline Models of Inherited Retinal Diseases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2024, 14, a041286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooney, A. Stability of Essential Nutrients in Pet Food Manufacturing and Storage. Master’s Thesis, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, USA, 2016. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/33382101.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Belay, T.; Lambrakis, L.; Goodgame, S.; Price, A.; Kersey, J.; Shields, R. 392 Vitamin Stability in wet pet food Formulation and Production perspective. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96 (Suppl. S3), 155–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastak, Y.; Pelletier, W. A cross-species perspective: β-carotene supplementation effects in poultry, swine, and cattle—A review. J.Appl. Anim. Res. 2024, 52, 2321957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, G.M.; Andretta, I.; Martinez, N.; Wernick, B.; Shastak, Y.; Gordillo, A.; Gobi, J. Stability of vitamin A at critical points in pet-feed manufacturing and during premix storage. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1309754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Retinol | Retinyl Stearate | Retinyl Palmitate + Oleate | Total Retinyl Esters | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dogs | 0.3–1.0 mg/L | 0.8–1.0 mg/L | 0.5–0.7 mg/L | 1.3–1.7 mg/L | [68] 1 |

| 0.6–0.8 mg/L | 0.9–0.1 mg/L | 0.6–0.7 mg/L | 1.5–1.7 mg/L | [69] 1 | |

| 0.9–1.3 mg/L | 0.23–0.45 mg/L | 0.3–0.4 mg/L | 0.53–0.85 mg/L | [64] 1 | |

| 2.3–4.1 µmol/L | 3.5–10.6 µmol/L | 1.4–6.2 µmol/L | 4.9–16.8 µmol/L | [70] 1 | |

| 2.7–3.4 µmol/L | Not measured | 4.5–12.0 * µmol/L | - | [71] 2 | |

| 642 ng/mol | 916 ng/mol | 609 ng/mol | 1525 ng/mol | [63] 1 | |

| Cats | 0.2–1.6 mg/L | 0.3–0.4 mg/L | 0.1–0.2 mg/L | 0.4–0.6 mg/L | [72] 1 |

| 0.24 mg/L | 0.4 mg/L | 0.3 mg/L | 0.7 mg/L | [66] 1 | |

| 366–533 nmol/L | 247–327 nmol/L | 162–203 nmol/L | 409–530 nmol/L | [54] 1 | |

| 213 ng/mol | 323 ng/mol | 165 ng/mol | 488 ng/mol | [63] 1 | |

| Humans | 0.065–3.14 μmol/L | - | - | 0.00–0.11 μmol/L | [73] 2 |

| 2.0–4.0 μmol/L | - | - | 0.1–0.2 μmol/L | [74] 1 | |

| 2.1–2.4 μmol/L | - | - | 0.054–0.056 μmol/L | [75] 2 |

| Species | Total Vitamin A | Retinol | Retinyl Stearate | Retinyl Palmitate/Oleate | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dogs | 0.44 ± 0.55 µg/mL | 0.22 ± 0.04 µg/mL | 0.006 ± 0.008 µg/mL | 0.21 ± 0.39 µg/mL | [64] |

| 0.6 ± 0.4 mg/L | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | [180] | |

| 580 ng/mL | Not measured | Not measured | Not measured | [54] | |

| Cats | 22 ± 21.0 ng/mL | Not detected | 15 ± 13.6 ng/mL | 9 ± 7.6 ng/mL/11 ± 17.5 ng/mL | [66] |

| 131 µg/dL | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | [180] |

| Source | Dogs | Cats |

|---|---|---|

| [183] | 33,330 IU/kg of diet | 100,000 IU/kg of diet |

| [11] | Puppies and breeding bitches: 50,000 IU/kg of diet Adult: 210,000 IU/kg of diet | 330,000 IU/kg of diet |

| [10] | 100,000 IU/1000 kcal of diet | - |

| [184] | 250,000 IU/kg of diet (DM basis) | 333,300 IU/kg of diet (DM basis) |

| [35] | 400,000 IU/kg of diet (DM basis) | Adult and growth: 400,000 IU/kg of diet (DM basis) Reproduction: 333,333 IU/kg of diet (DM basis) |

| Source | Dogs | Cats | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growing | Reproduction | Adult | Growing | Reproduction | Adult | |

| [33] | - | - | - | 3333 * | 5999 * | - |

| [32] | 3336 * | - | - | - | - | - |

| [11] | 3533 * | 3533 * | 3533 * | 3333 * | 6666 * | 3333 * |

| [35] | 5000 * | 5000 * | 6060–7020 * | 3333–4444 * | 9000 * | 9000 * |

| [184] | 5000 * | 5000 * | 5000 * | 6668 * | 6668 * | 3332 * |

| [219] | 8000–12,000 ** | 8000–12,000 ** | 8000–12,000 ** | 15,000–25,000 ** | 15,000–25,000 ** | 15,000–25,000 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shastak, Y.; Pelletier, W. Pet Wellness and Vitamin A: A Narrative Overview. Animals 2024, 14, 1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14071000

Shastak Y, Pelletier W. Pet Wellness and Vitamin A: A Narrative Overview. Animals. 2024; 14(7):1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14071000

Chicago/Turabian StyleShastak, Yauheni, and Wolf Pelletier. 2024. "Pet Wellness and Vitamin A: A Narrative Overview" Animals 14, no. 7: 1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14071000

APA StyleShastak, Y., & Pelletier, W. (2024). Pet Wellness and Vitamin A: A Narrative Overview. Animals, 14(7), 1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14071000