Guidance on Minimum Standards for Canine-Assisted Psychotherapy in Adolescent Mental Health: Delphi Expert Consensus on Health, Safety, and Canine Welfare

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

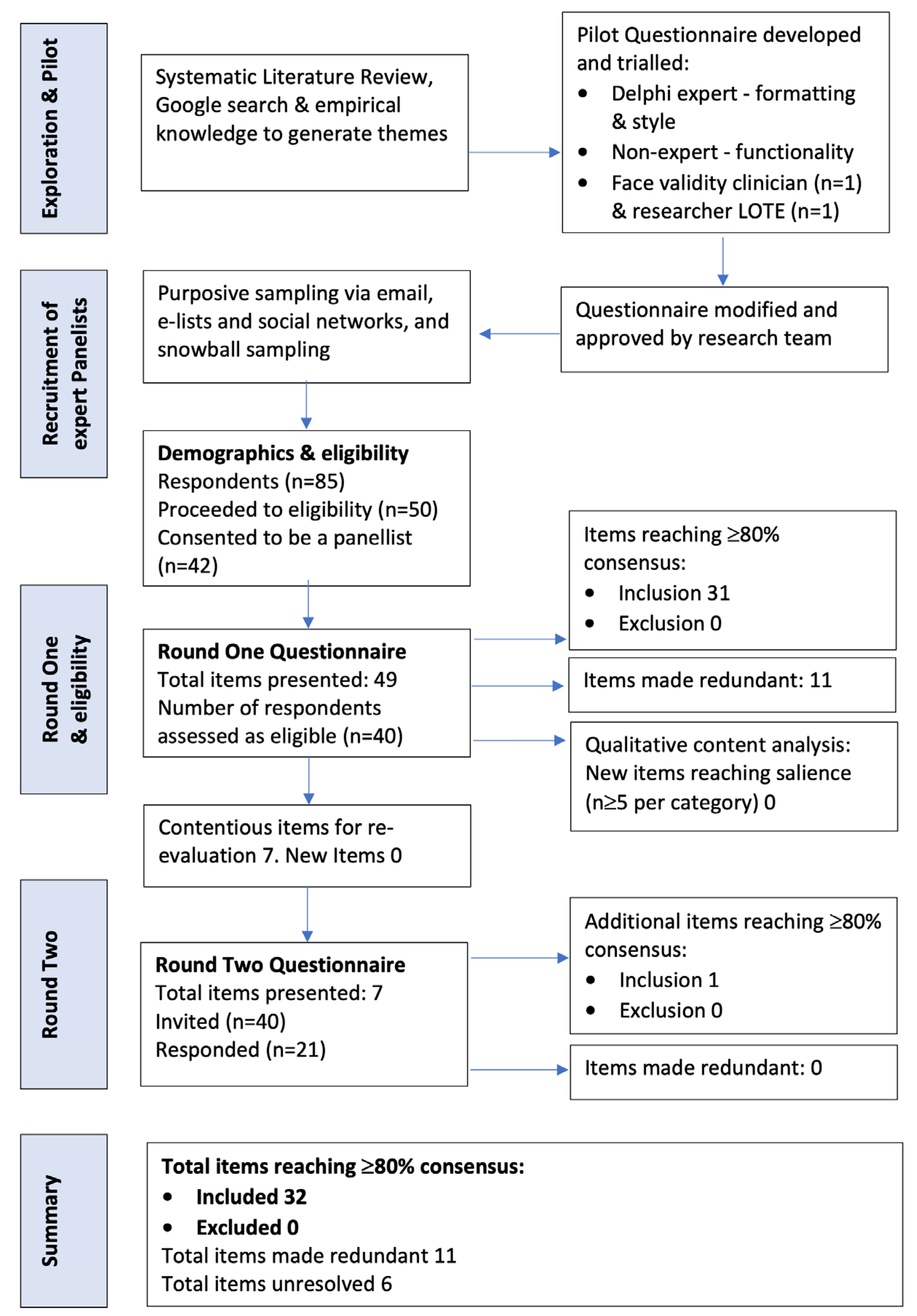

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Characteristics

3.2. Consensus Overview

3.3. Health and Safety

3.4. Welfare

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.1.1. Health and Safety

4.1.2. Welfare

4.2. Clinical Implications and Recommendations for Canine-Assisted Psychotherapy in Adolescent Mental Health

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodriguez, K.E.; Green, F.L.; Binfet, J.-T.; Townsend, L.; Gee, N.R. Complexities and Considerations in Conducting Animal-Assisted Intervention Research: A Discussion of Randomized Controlled Trials. Hum. Anim. Interact. 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Association of Human-Animal Interaction Organizations, IAHAIO. Iahaio White Paper 2014, Updated for 2018. In The IAHAIO Definitions for Animal Assisted Intervention and Guidelines for Wellness of Animals Involved in AAI; IAHAIO: Seattle, WA, USA, 2018; Available online: http://iahaio.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/iahaio_wp_updated-2018-final-1.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2019).

- Jones, M.G.; Rice, S.M.; Cotton, S.M. Who Let the Dogs Out? Therapy Dogs in Clinical Practice. Australas. Psychiatry 2018, 26, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, A.H.; Andersen, S.J. A Commentary on the Contemporary Issues Confronting Animal Assisted and Equine Assisted Interactions. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2021, 100, 103436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Z.; Morse, L.; Albright, J.; Viera, A.; Souza, M. Describing the Use of Animals in Animal-Assisted Intervention Research. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2019, 22, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brelsford, V.L.; Dimolareva, M.; Gee, N.R.; Meints, K. Best Practice Standards in Animal-Assisted Interventions: How the Lead Risk Assessment Tool Can Help. Animals 2020, 10, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meers, L.L.; Contalbrigo, L.; Samuels, W.E.; Duarte-Gan, C.; Berckmans, D.; Laufer, S.J.; Stevens, V.A.; Walsh, E.A.; Normando, S. Canine-Assisted Interventions and the Relevance of Welfare Assessments for Human Health, and Transmission of Zoonosis: A Literature Review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 899889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santaniello, A.; Sansone, M.; Fioretti, A.; Menna, L.F. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Occurrence of Eskape Bacteria Group in Dogs, and the Related Zoonotic Risk in Animal-Assisted Therapy, and in Animal-Assisted Activity in the Health Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, W.; Signal, T.; Judd, J.A. Fur, Fin, and Feather: Management of Animal Interactions in Australian Residential Aged Care Facilities. Animals 2022, 12, 3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, J.A.; Kruger, K.A.; Freeman, L.M.; Griffin, J.A.; Ng, Z.Y. Current Standards and Practices within the Therapy Dog Industry: Results of a Representative Survey of United States Therapy Dog Organizations. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grové, C.; Henderson, L.; Lee, F.; Wardlaw, P. Therapy Dogs in Educational Settings: Guidelines and Recommendations for Implementation. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 655104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiSalvo, H.; Haiduven, D.; Johnson, N.; Reyes, V.V.; Hench, C.P.; Shaw, R.; Stevens, D.A. Who Let the Dogs Out? Infection Control Did: Utility of Dogs in Health Care Settings and Infection Control Aspects. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2006, 34, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, S.F.; Corrigan, V.K.; Buechner-Maxwell, V.; Pierce, B.J. Evaluation of Risk of Zoonotic Pathogen Transmission in a University-Based Animal Assisted Intervention (Aai) Program. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerulo, G.; Kargas, N.; Mills, D.S.; Law, G.; VanFleet, R.; Faa-Thompson, T.; Winkle, M.Y. Animal-Assisted Interventions. Relationship between Standards and Qualifications. People Anim. Int. J. Res. Pract. 2020, 3, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Shue, S.J.; Winkle, M.Y.; Mulcahey, M.J. Integration of Animal-Assisted Therapy Standards in Pediatric Occupational Therapy. People Anim. Int. J. Res. Pract. 2018, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, S.B.; Gee, N.R. Canine-Assisted Interventions in Hospitals: Best Practices for Maximizing Human and Canine Safety. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 615730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santaniello, A.; Garzillo, S.; Cristiano, S.; Fioretti, A.; Menna, L.F. The Research of Standardized Protocols for Dog Involvement in Animal-Assisted Therapy: A Systematic Review. Animals 2021, 11, 2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurelli, M.P.; Santaniello, A.; Fioretti, A.; Cringoli, G.; Rinaldi, L.; Menna, L.F. The Presence of Toxocara Eggs on Dog’s Fur as Potential Zoonotic Risk in Animal-Assisted Interventions: A Systematic Review. Animals 2019, 9, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santaniello, A.; Varriale, L.; Dipineto, L.; Borrelli, L.; Pace, A.; Fioretti, A.; Menna, L.F. Presence of Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli in Dogs under Training for Animal-Assisted Therapies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, R.; Bearman, G.; Brown, S.; Bryant, K.; Chinn, R.; Hewlett, A.; George, B.G.; Goldstein, E.J.; Holzmann-Pazgal, G.; Rupp, M.E.; et al. Animals in Healthcare Facilities: Recommendations to Minimize Potential Risks. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 2015, 36, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, K.R.; Waite, K.B.; Ruble, K.; Carroll, K.C.; DeLone, A.; Frankenfield, P.; Serpell, J.A.; Thorpe, R.J.; Morris, D.O.; Agnew, J.; et al. Risks Associated with Animal-Assisted Intervention Programs: A Literature Review. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2020, 39, 101145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, S.L.; Golab, G.C.; Christensen, E.; Castrodale, L.; Aureden, K.; Bialachowski, A.; Gumley, N.; Robinson, J.; Peregrine, A.; Benoit, M.; et al. Guidelines for Animal-Assisted Interventions in Health Care Facilities. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2008, 36, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santaniello, A.; Perruolo, G.; Cristiano, S.; Agognon, A.L.; Cabaro, S.; Amato, A.; Dipineto, L.; Borrelli, L.; Formisano, P.; Fioretti, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Affects Both Humans and Animals: What Is the Potential Transmission Risk? A Literature Review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, S.L.; Reid-Smith, R.; Boerlin, P.; Weese, J.S. Evaluation of the Risks of Shedding Salmonellae and Other Potential Pathogens by Therapy Dogs Fed Raw Diets in Ontario and Alberta. Zoonoses Public Health 2008, 55, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overgaauw, P.A.; Vinke, C.M.; van Hagen, M.A.; Lipman, L.J. A One Health Perspective on the Human-Companion Animal Relationship with Emphasis on Zoonotic Aspects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runesvärd, E.; Wikström, C.; Hansson, I.; Fernström, L.-L. Presence of Pathogenic Bacteria in Faeces from Dogs Fed Raw Meat-Based Diets or Dry Kibble. Vet. Rec. 2020, 187, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.M.; Thomson, R.; Malone-Lee, J.; Ridgway, G.L. Cross-Infection between Animals and Man. Possible Feline Transmission of Staphylococcus Aureus Infection in Humans? J. Hosp. Infect. 1988, 12, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edner, A.; Lindstrom-Nilsson, M.; Melhus, A. Low Risk of Transmission of Pathogenic Bacteria between Children and the Assistance Dog during Animal-Assisted Therapy If Strict Rules Are Followed. J. Hosp. Infect. 2021, 115, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandra, B.; Vokes, R.; Barker, R. Animal-Assisted Interventions in Health Care Settings. A Best Practices Manual for Establishing New Programs; Purdue University: Lafayette, IN, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Safe-Work-Australia. How to Manage Work Health and Safety Risks. Code of Practice; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2011. Available online: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/1702/how_to_manage_whs_risks.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Fine, A.H.; Griffin, T.C. Protecting Animal Welfare in Animal-Assisted Intervention: Our Ethical Obligation. Semin. Speech Lang. 2022, 43, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijnen, B.; Martens, P. Animals in Animal-Assisted Services: Are They Volunteers or Professionals? Animals 2022, 12, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignot, A.; de Luca, K.; Servais, V.; Leboucher, G. Handlers’ Representations on Therapy Dogs’ Welfare. Animals 2022, 12, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Z. Strategies to Assessing and Enhancing Animal Welfare in Animal-Assisted Interventions. In The Welfare of Animals in Animal-Assisted Interventions; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 123–154. [Google Scholar]

- Glenk, L.M.; Foltin, S. Therapy Dog Welfare Revisited: A Review of the Literature. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, J.; Fine, A. (Eds.) The Welfare of Animals in Animal-Assisted Interventions. Foundations and Best Practice Methods; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Glenk, L.M. A Dog’s Perspective on Animal-Assisted Interventions. In Pets as Sentinels, Forecasters and Promoters of Human Health; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 349–365. [Google Scholar]

- McDowall, S.; Hazel, S.J.; Cobb, M.; Hamilton-Bruce, A. Understanding the Role of Therapy Dogs in Human Health Promotion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berns, G. Decoding the Canine Mind. Cerebrum 2020, 2020, cer-04-20. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, L.; Gee, N.R. Recognizing and Mitigating Canine Stress During Animal Assisted Interventions. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, D.J. Operational Details of the Five Domains Model and Its Key Applications to the Assessment and Management of Animal Welfare. Animals 2017, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, D.J.; Beausoleil, N.J.; Littlewood, K.E.; McLean, A.N.; McGreevy, P.D.; Jones, B.; Wilkins, C. The 2020 Five Domains Model: Including Human-Animal Interactions in Assessments of Animal Welfare. Animals 2020, 10, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menna, L.F.; Santaniello, A.; Todisco, M.; Amato, A.; Borrelli, L.; Scandurra, C.; Fioretti, A. The Human-Animal Relationship as the Focus of Animal-Assisted Interventions: A One Health Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hediger, K.; Meisser, A.; Zinsstag, J. A One Health Research Framework for Animal-Assisted Interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, D.; Dell, C.A. Applying One Health to the Study of Animal-Assisted Interventions. Ecohealth 2015, 12, 560–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marit, C.; Carlone, B.; Guerrini, F.; Ricci, E.; Zilocchi, M.; Gazzano, A. Do.C.: A Behavioral Test for Evaluating Dogs’ Suitability for Working in the Classroom. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2013, 8, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfarth, R.; Olbrich, E. Quality Development and Quality Assurance in Practical Animal-Assisted Interventions; European Society for Animal-Assisted Therapy (ESAAT); The International Society for Animal-Assisted Therapy (ISAAT): Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2014; Available online: https://isaat.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Qualitaetskriterien_e-1.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Mongillo, P.; Pitteri, E.; Adamelli, S.; Bonichini, S.; Farina, L.; Marinelli, L. Validation of a Selection Protocol of Dogs Involved in Animal-Assisted Intervention. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2015, 10, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Z.Y.; Pierce, B.J.; Otto, C.M.; Buechner-Maxwell, V.A.; Siracusa, C.; Werre, S.R. The Effect of Dog–Human Interaction on Cortisol and Behavior in Registered Animal-Assisted Activity Dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 159, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.G.; Filia, K.; Rice, S.; Cotton, S. Guidance on Minimum Standards for Canine-Assisted Psychotherapy in Adolescent Mental Health: Delphi Expert Consensus on Terminology, Qualifications and Training. Hum. Anim. Interact. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrafchi, A.; David-Steel, M.; Pearce, S.D.; de Zwaan, N.; Merkies, K. Effect of Human-Dog Interaction on Therapy Dog Stress During an on-Campus Student Stress Buster Event. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2022, 253, 105659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F. Using the Delphi Expert Consensus Method in Mental Health Research. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2015, 49, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, D.; Moseley, L. The Use of the Delphi as a Research Approach. Nurse Res. 2001, 8, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, P.R.; Beehler, G.P.; Donnelly, K.; Funderburk, J.S.; Wray, L.O. A Practical Guide to Applying the Delphi Technique in Mental Health Treatment Adaptation: The Example of Enhanced Problem-Solving Training (E-Pst). Prof. Psychol. Res. Pr. 2021, 52, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.G.; Rice, S.M.; Cotton, S.M. Incorporating Animal-Assisted Therapy in Mental Health Treatments for Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Canine-Assisted Psychotherapy. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jünger, S.; Payne, S.A.; Brine, J.; Radbruch, L.; Brearley, S.G. Guidance on Conducting and Reporting Delphi Studies (Credes) in Palliative Care-Recommendations Based on a Methodological Systematic Review. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 684–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, I.R.; Grant, R.C.; Feldman, B.M.; Pencharz, P.B.; Ling, S.C.; Moore, A.M.; Wales, P.W. Defining Consensus: A Systematic Review Recommends Methodologic Criteria for Reporting of Delphi Studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The Qualitative Content Analysis Process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, A.F.; Chur-Hansen, A.; Winefield, H.R. Australian Psychologists’ Knowledge of and Attitudes towards Animal-Assisted Therapy. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 15, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.P.; Dale, A.A. Integrating Animals in the Classroom. The Attitudes and Experiences of Australian School Teachers toward Animal-Assisted Interventions for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Pet Behav. Sci. 2016, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Almqvist, C.; Larsson, P.H.; Egmar, A.-C.; Hedrén, M.; Malmberg, P.; Wickman, M. School as a Risk Environment for Children Allergic to Cats and a Site for Transfer of Cat Allergen to Homes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1999, 103, 1012–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, M.; Kaufmann, M. Ensuring Animal Well-Being in Animal-Assisted Service Programs: Ethics Meets Practice Learning at Green Chimneys. Hum. Anim. Interact. 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkle, M.; Johnson, A.; Mills, D. Dog Welfare, Well-Being and Behavior: Considerations for Selection, Evaluation and Suitability for Animal-Assisted Therapy. Animals 2020, 10, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leconstant, C.; Spitz, E. Integrative Model of Human-Animal Interactions: A One Health-One Welfare Systemic Approach to Studying Hai. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 656833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Z.; Albright, J.; Fine, A.; Peralta, J. Our Ethical and Moral Responsibility: Ensuring the Welfare of Therapy Animals. In Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy: Theoretical Foundations and Guidelines for Animal-Assisted Interventions; Fine, A., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2015; pp. 357–376. [Google Scholar]

- Fatjó, J.; Bowen, J.; Calvo, P. Stress in Therapy Animals. In The Welfare of Animals in Animal-Assisted Interventions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 91–121. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Y.; Serpell, J.A.; McGrath, S.; Bartner, L.R.; Rao, S.; Packer, R.A.; Gustafson, D.L. Development and Validation of a Questionnaire for Measuring Behavior and Temperament Traits in Pet Dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2003, 223, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurama, M.; Ito, M.; Nakanowataru, Y.; Kooriyama, T. Selection of Appropriate Dogs to Be Therapy Dogs Using the C-Barq. Animals 2023, 13, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulmer, A.E.; Laven, L.J.; Hill, K.E. Quality of Life Measurement in Dogs and Cats: A Scoping Review of Generic Tools. Animals 2022, 12, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Z.; Fine, A. A Trajectory Approach to Supporting Therapy Welfare in Retirement and Beyond. In The Welfare of Animals in Animal-Assisted Interventions. Foundations and Best Practice Methods; Peralta, J., Fine, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 243–264. [Google Scholar]

- Glenk, L.M.; Kothgassner, O.D.; Stetina, B.U.; Palme, R.; Kepplinger, B.; Baran, H. Assessing Therapy Dogs’ Welfare in Animal-Assisted Interventions. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2013, 8, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorczyca, K.; Fine, A.; Spain, V.; Callaghan, D.; Nelson, L.; Popejoy, L.; Wong, B.; Wong, S. History, Development, and Theory of Human-Animal Support Servies for People with Aids/Hiv and Other Disablling Chronic Conditions. In Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy. Foundations and Guidelines for Animal-Assisted Interventions; Fine, A., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 303–354. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.Y.; Ngai, J.T.K.; Chau, K.K.Y.; Yu, R.W.M.; Wong, P.W.C. Development of a Pilot Human-Canine Ethogram for an Animal-Assisted Education Programme in Primary Schools—A Case Study. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2022, 255, 105725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartashova, I.; Ganina, K.; Karelina, E.; Tarasov, S. How to Evaluate and Manage Stress in Dogs—A Guide for Veterinary Specialist. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 243, 105458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremhorst, A.; Mills, D. Working with Companion Animals, and Especially Dogs, in Therapeutic and Other Aai Settings. In The Welfare of Animals in Animal-Assisted Interventions; Peralta, J., Fine, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Demographics | Response | Frequency (n) | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country of residence | United States of America | 17 | 42.5 |

| Australia | 12 | 30 | |

| Europe | 8 | 22.5 | |

| UK | 1 | 2.5 | |

| South America | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Undisclosed | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Cultural identity/ethnicity | Caucasian (e.g., “White”, “Anglo”, “European”, “Australian”) | 30 | 65 |

| Hispanic | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Ashkenazi Jewish | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Undisclosed | 8 | 20 | |

| Language(s) spoken | English only | 28 | 70 |

| English in addition to other language(s) | 9 | 22.5 | |

| Undisclosed | 3 | 7.5 | |

| Gender identity | Female | 37 | 92.5 |

| Male | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Non-binary | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Undisclosed | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Age range | Youngest 27 years | Mean Age | |

| Eldest 76 years | 48.58 years | ||

| AAT Expertise | Response | Frequency (n) | Percentage % |

| Primary occupation | Teacher/educator | 12 | 52.5 |

| Researcher | 13 | 60 | |

| Provider of AAT | 31 | 77.5 | |

| Primary species | Dog | 31 | 77.5 |

| Horse | 15 | 37.5 | |

| Farm animal (“chicken”, “goat”, “donkey”, “sheep”) | 7 | 17.5 | |

| Cat | 5 | 12.5 | |

| Small animal (“rat”, “hamster”) | 5 | 12.5 | |

| Bird/aviary | 2 | 5 | |

| Reptile | 2 | 5 | |

| Other (“dolphin”) | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Total years AAT experience | 5–10 years | 18 | 45 |

| 11–15 years | 10 | 25 | |

| 16 years or more | 12 | 30 | |

| Mental health qualifications (e.g., “Psychology”, “Counselling & Psychotherapy”, “Social Work”, etc.) | Secondary/diploma | 0 | 0 |

| Tertiary/degree | 2 | 5 | |

| Post-graduate | 38 | 95 | |

| AAT training | Self-directed CPD/CE (e.g., conferences, books, workshops) | 15 | 37.5 |

| Short course, certificate | 25 | 62.5 | |

| Certified, accredited, or registered with an organization | 24 | 60 | |

| Tertiary degree (or equivalent) | 3 | 7.5 | |

| Post-graduate (e.g., thesis) | 6 | 15 | |

| Supervised practice/internship | 3 | 7.5 | |

| Dog trainer, dog behavior training | 5 | 12.5 | |

| AAT consultant, supervisor, legislator, conference speaker, postgraduate course developer | 8 | 20 | |

| AAT peer-reviewed publications | Nil | 8 | 20 |

| 1–4 | 18 | 45 | |

| 5–10 | 4 | 10 | |

| 11 or more | 10 | 25 |

| Item 1 | Consensus 2 | Mean and SD 3 | Median Rating 3 | Round |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health and Safety | ||||

| Providers trained in zoonoses and risk reduction | 100% | 4.7 (0.5) | 5 | 1 |

| Providers trained and qualified in human first aid | 89.3% | 4.4 (0.8) | 5 | 1 |

| Providers trained in canine first aid | 96.4% | 4.4 (0.6) | 4 | 1 |

| Providers up to date with all relevant (human) vaccines | 85.8% | 4.4 (1.0) | 5 | 1 |

| Canines up to date on all relevant vaccines | 100% | 4.9 (0.3) | 5 | 1 |

| Canines up to date on internal/external parasite control | 100% | 4.9 (0.3) | 5 | 1 |

| Canines obtain regular vet clearance (6–12 monthly) | 96.4% | 4.8 (0.5) | 5 | 1 |

| Canines do not work when showing signs of illness | 100% | 5.0 (0.2) | 5 | 1 |

| Canines do not work when unhappy/behavior indicating not wanting to work | 100% | 4.9 (0.3) | 5 | 1 |

| Zoonotic clearance to work obtained following illness | 82.2% | 4.5 (0.8) | 5 | 1 |

| Canines with illness, injury, or disability obtain vet clearance to work | 87.5% | 4.4 (0.8) | 5 | 1 |

| Canines do not work when on heat/in season | 88.2% | 4.4 (1.3) | 5 | 2 |

| Clients use hand hygiene before and after canine contact | 92.8% | 4.5 (0.9) | 5 | 1 |

| Canines are prevented from licking client’s mouth or eyes | 81.5% | 4.3 (0.9) | 5 | 1 |

| Canines are hydrobathed when obviously soiled/malodorous | 85.7% | 4.3 (1.1) | 5 | 1 |

| Canines are groomed every workday | 92.8% | 4.5 (0.7) | 5 | 1 |

| Risk assessment of venue/environment | 100% | 4.8 (0.5) | 5 | 1 |

| Risk assessment of client–animal interaction | 97.0% | 4.9 (0.3) | 5 | 1 |

| Incident reporting completed for ALL injuries (human/animal) (physical/psychological) | 92.9% | 4.6 (0.6) | 5 | 1 |

| Incident reporting completed for all ‘near miss’ incidents | 92.9% | 4.4 (0.6) | 4.5 | 1 |

| Incident reporting includes review of risk, plus future management, or mitigation | 100% | 4.9 (0.4) | 5 | 1 |

| Any minor injury washed (5 min) + first aid and reported | 89.3% | 4.4 (0.9) | 5 | 1 |

| Any minor injury washed (45 s) + first aid and reported | 96.3% | 4.7 (0.6) | 5 | 1 |

| Item 1 | Consensus 2 | Mean and SD 3 | Median Rating 3 | Round |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welfare | ||||

| Providers are trained in canine welfare and body language | 100% | 4.8 (0.4) | 5 | 1 |

| Canine welfare is assessed by informal provider observations during work | 100% | 4.7 (0.5) | 5 | 1 |

| Canine welfare is assessed and documented by provider in canine health record | 85.8% | 4.2 (0.9) | 4 | 1 |

| Canine welfare is maintained by flexible response to observations | 89.2% | 4.4 (0.8) | 5 | 1 |

| Canines are free to engage, disengage, rest (e.g., off-lead) in sessions | 96.3% | 4.7 (0.7) | 5 | 1 |

| Suitability assessment of venue/environment | 100% | 4.8 (0.4) | 5 | 1 |

| Animal familiarization with venue/setting prior to group therapy | 84.9% | 4.2 (1.0) | 4 | 1 |

| Client–animal familiarization occurs during group therapy (therapeutic process) | 90.7% | 4.4 (0.8) | 5 | 1 |

| Human and animal welfare are given equal importance | 96.4% | 4.8 (0.5) | 5 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jones, M.G.; Filia, K.; Rice, S.M.; Cotton, S.M. Guidance on Minimum Standards for Canine-Assisted Psychotherapy in Adolescent Mental Health: Delphi Expert Consensus on Health, Safety, and Canine Welfare. Animals 2024, 14, 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14050705

Jones MG, Filia K, Rice SM, Cotton SM. Guidance on Minimum Standards for Canine-Assisted Psychotherapy in Adolescent Mental Health: Delphi Expert Consensus on Health, Safety, and Canine Welfare. Animals. 2024; 14(5):705. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14050705

Chicago/Turabian StyleJones, Melanie G., Kate Filia, Simon M. Rice, and Sue M. Cotton. 2024. "Guidance on Minimum Standards for Canine-Assisted Psychotherapy in Adolescent Mental Health: Delphi Expert Consensus on Health, Safety, and Canine Welfare" Animals 14, no. 5: 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14050705

APA StyleJones, M. G., Filia, K., Rice, S. M., & Cotton, S. M. (2024). Guidance on Minimum Standards for Canine-Assisted Psychotherapy in Adolescent Mental Health: Delphi Expert Consensus on Health, Safety, and Canine Welfare. Animals, 14(5), 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14050705