Detection of Candidate Genes Associated with Fecundity through Genome-Wide Selection Signatures of Katahdin Ewes

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Declarations

2.2. Phenotypes

2.3. Genotypes

2.4. Population Structure

2.5. Selection Signatures

2.6. Detection of Candidate Genes

3. Results

3.1. Population Structure

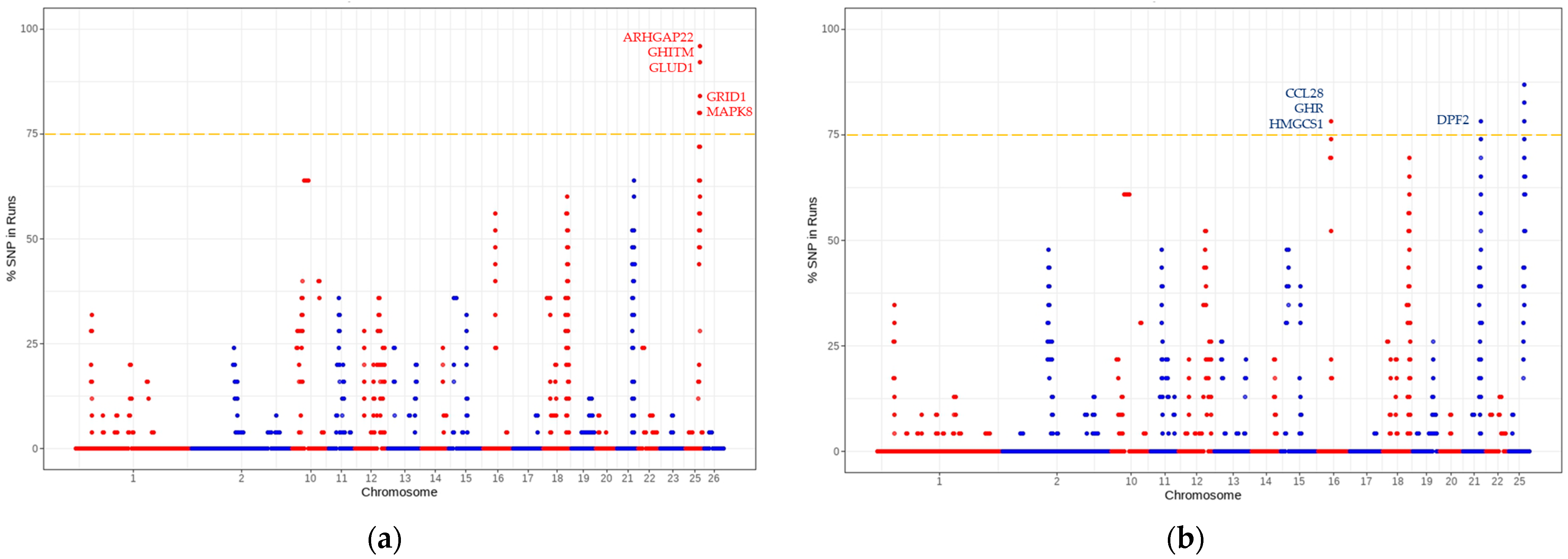

3.2. Candidate Genes

4. Discussion

4.1. Population Structure

4.2. Candidate genes

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vázquez-Martínez, I.; Jaramillo-Villanueva, J.L.; Bustamante-González, Á.; Vargas-López, S.; Calderón-Sánchez, F.; Torres-Hernández, G.; Pittroff, W. Structure and typology of sheep production units in central México. Agric. Soc. Y Desarro. 2018, 15, 85–97. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1870-54722018000100085&lng=es&tlng=en (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Gootwine, E. Invited review: Opportunities for genetic improvement toward higher prolificacy in sheep. Small Rumin. Res. 2020, 186, 106090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, T.; Stoikova-Grigorova, R.; Bozhilova-Sakova, M.; Ignatova, M.; Dimitrova, I.; Koutev, V. Phenotypic and genetic characteristics of fecundity in sheep. A review. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 27, 1002–1008. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Milena-Bozhilova/publication/356064326_Phenotypic_and_genetic_characteristics_of_fecundity_in_sheep_A_review/links/618a82d6d7d1af224bca6ba5/Phenotypic-and-genetic-characteristics-of-fecundity-in-sheep-A-review.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Davis, T.C.; White, R.R. Breeding animals to feed people: The many roles of animal reproduction in ensuring global food security. Theriogenology 2020, 150, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chay-Canul, A.J.; García-Herrera, R.A.; Magaña-Monforte, J.G.; Macias-Cruz, U.; Luna-Palomera, C. Productividad de ovejas Pelibuey y Katahdin en el trópico húmedo. Ecosistemas Y Recur. Agropecu. 2019, 6, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNO. 2022. Available online: https://www.uno.org.mx/razas_ovinas/katahdin.html (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- González-Godínez, A.; Urrutia-Morales, J.; Gámez-Vázquez, H.G. Comportamiento reproductivo de ovejas Dorper y Katahdin empadradas en primavera en el norte de México. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2014, 17, 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasi, H.; Abdollahi-Arpanahi, R. The candidate genes and pathways affecting litter size in sheep. Small Rumin. Res. 2021, 205, 106546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Li, F.; Zhang, D.; Li, X.; Zhanga, Y.; Zhaoa, Y.; Zhaoa, L.; Xua, D.; et al. Molecular characterization and expression of RPS23 and HPSE and their association with hematologic parameters in sheep. Gene 2022, 837, 146654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreselassie, G.; Berihulay, H.; Jiang, L.; Ma, Y. Review on Genomic Regions and Candidate Genes Associated with Economically Important Production and Reproduction Traits in Sheep (Ovies aries). Animals 2019, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; Van den Hurk, R.; Van Tol, H.; Roelen, B.; Figueiredo, J. Expression of growth differentiation factor 9 (GDF9), bone morphogenetic protein 15 (BMP15), and BMP receptors in the ovaries of goats. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2005, 70, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosrati, M.; Asadollahpour Nanaei, H.; Amiri Ghanatsaman, Z.; Esmailizadeh, A. Whole genome sequence analysis to detect signatures of positive selection for high fecundity in sheep. Reprod. Domes. Anim. 2018, 54, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockrum, R.R.; Pickering, N.K.; Anderson, R.M.; Hyndman, D.L.; Bixley, M.J.; Dodds, K.G.; Stobart, R.H.; McEwan, J.C.; Cammack, K.M. Identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with feed efficiency in rams. Proc. West. Sect. Am. Soc. Anim. Sci. 2012, 63, 79–83. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265382096_IDENTIFICATION_OF_SINGLE_NUCLEOTIDE_POLYMORPHISMS_ASSOCIATED_WITH_FEED_EFFICIENCY_IN_RAMS (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Xu, S.-S.; Gao, L.; Xie, X.-L.; Ren, Y.-L.; Shen, Z.-Q.; Wang, F.; Shen, M.; Eyϸórsdóttir, E.; Hallsson, J.H.; Kiseleva, T.; et al. Genome-wide association analyses highlight the potential for different genetic mechanisms for litter size among sheep breeds. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Yang, J.; Shen, M.; Xie, X.-L.; Liu, G.-J.; Xu, Y.-X.; Lv, F.-H.; Yang, H.; Yang, Y.-L.; Liu, C.-B.; et al. Whole-genome resequencing of wild and domestic sheep identifies genes associated with morphological and agronomic traits. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, B. Overview of statistical methods for genome-wide association studies (GWAS). Genome-wide association studies and genomic prediction. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 1019, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez, D.F.; Sánchez, L.F.; Moreno, V.; Moratalla-Navarro, F.; Molina de la Torre, A.J.; Martín Sánchez, V. GASVeM: A new machine learning methodology for multi-SNP analysis of GWAS data based on genetic algorithms and support vector machines. Mathematics 2021, 9, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortezaei, Z.; Tavallaei, M. Novel directions in data pre-processing and genome-wide association study (GWAS) methodologies to overcome ongoing challenges. IMU 2021, 24, 100586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, K.M.; McEwan, J.C.; Dodds, K.G.; Gemmell, N.J. Signatures of selection in sheep bred for resistance or susceptibility to gastrointestinal nematodes. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, K.A.; Panigrahi, M.; Kumar, H.; Bhushan, B.; Dutt, T.; Mishra, B.P. Selection signatures in livestock genome: A review of concepts, approaches, and applications. Livest. Sci. 2020, 241, 104257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COLPOS (Colegio de Postgraduados). Reglamento para el uso y Cuidado de Animales Destinados a la Investigación en el Colegio de Postgraduados; Dirección de Investigación: Colegio de Posgraduados: Montecillo, México, 2019. Available online: http://www.colpos.mx/wb_pdf/norma_interna/reglamento_usoycuidadoanimales_050819.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- SAGARPA (Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca, y Alimentación). Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-062-ZOO-1999, Especificaciones Técnicas para la Producción, Cuidado y uso de los Animales de Laboratorio; Diario Oficial de La Federación: Ciudad de México, México, 2001; pp. 107–165. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/203498/NOM-062-ZOO-1999_220801.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- García, E. Modificaciones al Sistema de Clasificación Climática de Köppen: Para Adaptarlo a las Condiciones de la República Mexicana, 5th ed.; Instituto de Geografía: UNAM México: Ciudad de México, México, 2004. Available online: http://www.publicaciones.igg.unam.mx/index.php/ig/catalog/view/83/82/251-1 (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Champely, S.; pwr: Basic Functions for Power Analysis. R Package Version 1.3-0. 2020. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pwr (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Galili, T. dendextend: An R package for visualizing, adjusting, and comparing trees of hierarchical clustering. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3718–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jombart, T.; Ahmed, I. adegenet 1.3-1: New tools for the analysis of genome-wide SNP data. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 3070–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.R.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; Bakker, P.I.W.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: A toolset for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biscarini, F.; Cozzi, P.; Gaspa, G.; Marras, G. detectRUNS: Detect Runs of Homozygosity and Runs of Heterozygosity in Diploid Genomes. R Package Version 0.9.6. 2019. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=detectRUNS (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Paradis, E. pegas: An R package for population genetics with an integrated-modular approach. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 419–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sozoniuk, M.; Jamio, M.; Kankofer, M.; Kowalczyk, K. Reference gene selection in bovine caruncular epithelial cells under pregnancy-associated hormones exposure. Res. Sq. 2022, 12, 12742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kravitz, A.; Pelzer, K.; Sriranganathan, N. The paratuberculosis paradigm examined: A review of host genetic resistance and innate immune fitness in mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 721706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, N.; Wu, G.; Bazer, F.W. Regulation of gene expression by amino acids in animal cells. In Amino Acids in Nutrition and Health; Wu, G., Ed.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1332, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulus, J.; Kulus, M.; Kranc, W.; Jopek, K.; Zdun, M.; Józkowiak, M.; Jaśkowski, J.M.; Piotrowska-Kampisty, H.; Bukowska, D.; Antosok, P.; et al. Transcriptomic profile of new gene markers encoding proteins responsible for structure of porcine ovarian granulosa cells. Biology 2021, 10, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Dai, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, G.; Zheng, Z. Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Patterns of Muscle and Tail-Fat in Dairy Meade Sheep and Mongolian Sheep. Animals 2022, 12, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Cao, J.; Wu, M.; Ma, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, R.; Zhao, F.; Wei, C.; Du, L. Genome-wide specific selection in three domestic sheep breeds. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Elbeltagy, A.; Aboul-Naga, A.; Rischkowsky, B.; Sayre, B.; Mwacharo, J.; Rothschild, M. Multiple genomic signatures of selection in goats and sheep indigenous to a hot arid environment. Heredity 2015, 116, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Zhao, W.; Wang, G.; Gao, S. Selection of candidate genes for differences in fat metabolism between cattle subcutaneous and perirenal adipose tissue based on RNA-seq. Anim. Biotechnol. 2021, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.; Yin, T.; Swalve, H.; König, S. Single-step genomic best linear unbiased predictor genetic parameter estimations and genome-wide associations for milk fatty acid profiles, interval from calving to first insemination, and ketosis in Holstein cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 10921–10933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piersanti, R.; Horlock, A.; Block, J.; Santos, J.; Sheldon, I.; Bromfield, J. Persistent effects on bovine granulosa cell transcriptome after resolution of uterine disease. Reproduction 2019, 158, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Feng, X.; Muhatai, G.; Wang, L. Expression profile analysis of sheep ovary after superovulation and estrus synchronisation treatment. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 8, 1276–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholizadeh, M.; Esmaeili-Fard, S.M. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for litter size in sheep. Theriogenology 2022, 180, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinhauser, C.B.; Lambo, C.A.; Askelson, K.; Burns, G.W.; Behura, S.K.; Spencer, T.E.; Bazer, F.W.; Satterfield, M.C. Placental transcriptome adaptations to maternal nutrient restriction in sheep. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Y.; Xie, Y.; Zhu, M.; Yang, H.; Zhao, Z. MicroRNA-200c Mediates the Mechanism of MAPK8 Gene Regulating Follicular Development in sheep. Kafkas Univ. Vet. Fak. Derg. 2021, 27, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldenegodguad, M.; Pokharel, K.; Niiranen, L.; Soppela, P.; Ammosov, I.; Honkatukia, M.; Lindeberg, H.; Peippo, J.; Reilas, T.; Mazzullo, N.; et al. Adipose gene expression profiles reveal insights into the adaptation of northern Eurasian semi-domestic reindeer (Rangifer tarandus). Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, T.C.; de Souza, T.C.; Rovadoscki, G.A.; Coutinho, L.L.; Mourão, G.B.; de Camargo, G.M.F.; Costa, R.B.; de Carvalho, G.G.P.; Pedrosa, V.B.; Pinto, L.F.B. Genome-wide association for plasma urea concentration in sheep. Livest. Sci. 2021, 248, 104483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailidou, S.; Tsangaris, G.T.; Tzora, A.; Skoufos, I.; Banos, G.; Argiriou, A.; Arsenos, G. Analysis of genome-wide DNA arrays reveals the genomic population structure and diversity in autochthonous Greek goat breeds. PLoS ONE 2016, 14, e0226179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.; Cho, S.; Park, J.S.; Lee, Y.G.; Kim, N.; Kang, Y.K. Transcriptomic features of bovine blastocysts derived by somatic cell nuclear transfer. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2015, 5, 2527–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, N.; Duffy, G.B.; McGettigan, P.A.; Browne, J.A.; Mehta, J.P.; Kelly, A.K.; Mansouri-Attia, N.; Sandra, O.; Loftus, B.J.; Crowe, M.A.; et al. Evidence for an early endometrial response to pregnancy in cattle: Both dependent upon and independent of interferon tau. Physiol. Genomics 2012, 44, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meurens, F.; Whale, J.; Brownlie, R.; Dybvig, T.; Thompson, D.; Gerdts, V. Expression of mucosal chemokines TECK/CCL25 and MEC/CCL28 during fetal development of the ovine mucosal immune system. Immunology 2007, 120, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobanoglu, O.; Kul, E.; Gurcan, E.; Abaci, S.; Cankaya, S. Determination of the association of GHR/AluI gene polymorphisms with milk yield traits in Holstein and Jersey cattle raised in Turkey. Arch. Anim. Breed. 2021, 64, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, M.; Dionissopoulos, L.; AlZahal, O.; Doelman, J.; McBride, B. Rumen epithelial adaptation to ruminal acidosis in lactating cattle involves the coordinated expression of insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins and a cholesterolgenic enzyme. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Yu, J.; Hu, X.; Xiang, M.; Xia, Y.; Tao, B.; Du, X.; Wang, D.; Zhao, S.; Chen, H. Identification of reliable reference genes for expression studies in maternal reproductive tissues and foetal tissues of pregnant cows. Reprod. Dom. Anim. 2020, 55, 1554–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrode, R.; Ojango, J.M.K.; Okeyo, A.M.; Mwacharo, J.M. Genomic selection and use of molecular tools in breeding programs for indigenous and crossbred cattle in developing countries: Current status and future prospects. Front. Genet. 2019, 9, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Z.; Sun, W.; Guo, T.; Li, J.; Zhu, S.; Lu, Z.; Qiao, G.; Han, M.; Zhao, H.; Yang, B.; et al. Genome-wide selective signatures reveal candidate genes associated with hair follicle development and wool shedding in sheep. Gene 2021, 12, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, I.N.H.; Bessa, A.F.d.O.; Rola, L.D.; Genuíno, M.V.H.; Rocha, I.M.; Marcondes, C.R.; Righetti, M.C.; de Correia, A.R.L.; Prado, M.D.; Pearse, B.D.; et al. Cross-population selection signatures in Canchim composite beef cattle. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iffland, H.; Wellmann, R.; Schmid, M.; Preuß, S.; Tetens, J.; Bessei, W.; Bennewitz, J. Genome wide mapping of selection signatures and genes for extreme feather pecking in two divergently selected laying hen lines. Animals 2020, 10, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujano-Chavez, M.Z.; Ruíz-Flores, A.; López-Ordaz, R.; Pérez-Rodríguez, P. Genetic diversity in reproductive traits of Braunvieh cattle determined with SNP markers. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 8, 1709–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijas, J.W.; Hadfield, T.; Naval, S.M.; Cockett, N. Genome-wide association reveals the locus responsible for four-horned ruminant. Anim Genet. 2016, 47, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, B.O.; Curi, R.A.; Baldi, F.; Feitosa, F.L.B.; Andrade, W.B.F.D.; Albuquerque, L.G.D.; Oliveira, H.N.D.; Chardulo, L.A.L. Polymorphisms in candidate genes and their association with carcass traits and meat quality in Nellore cattle. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 2014, 49, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, H.; Rafat, S.; Moradi Shahrbabak, H.; Shodja, J.; Moradi, M. Genome-wide association study and gene ontology for growth and wool characteristics in Zandi sheep. JLST. 2020, 8, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Xie, M.; Chen, W.; Talbot, R.; Maddox, J.F.; Faraut, T.; Wu, C.; Muzny, D.M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; et al. The sheep genome illuminates biology of the rumen and lipid metabolism. Science 2014, 344, 1168–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Chen, L.; Tian, S.; Lin, Y.; Tang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Li, D.; Yeung, C.K.; Che, T.; Jin, L.; et al. Comprehensive variation discovery and recovery of missing sequence in the pig genome using multiple de novo assemblies. Genome Res. 2016, 27, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yurchenko, A.A.; Deniskova, T.E.; Yudin, N.S.; Dotsev, A.V.; Khamiruev, T.N.; Selionova, M.I.; Egorov, S.V.; Reyer, H.; Wimmers, K.; Zinovieva, N.A.; et al. High-density genotyping reveals signatures of selection related to acclimation and economically important traits in 15 local sheep breeds from Russia. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, P.; Id-Lahoucine, S.; Reverter, A.; Medrano, J.; Fortes, M.; Casellas, J.; Miglior, F.; Brito, L.; Carvalho, M.R.S.; Schenkel, C.F.S.; et al. Combining multi-OMICs information to identify key-regulator genes for pleiotropic effect on fertility and production traits in beef cattle. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relav, L.; Estienne, A.; Price, C.A. Dual-specificity phosphatase 6 (DUSP6) mRNA and protein abundance is regulated by fibroblast growth factor 2 in sheep granulosa cells and inhibits c-Jun N-terminal kinase (MAPK8) phosphorylation. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2021, 531, 111297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fecundity Group | Start SNP | End SNP | Chromosome | Number of SNP | Position (bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | To | |||||

| Low | oar3_OAR6_36225598 | oar3_OAR6_36295143 | 6 | 6 | 36225598 | 36295143 |

| Low | Chr16:31054761 | Chr16:31867174 | 16 | 11 | 31054761 | 31867174 |

| Low | OAR16_31491759.1 | OAR16_31817206.1 | 16 | 3 | 31491759 | 31817206 |

| Low | oar3_OAR16_31358348 | oar3_OAR16_31643375 | 16 | 3 | 31358348 | 31643375 |

| Low | Chr21:42744589 | Chr21:42752272 | 21 | 3 | 42744589 | 42752272 |

| High | Chr25:36456595 | Chr25:37312419 | 25 | 20 | 36456595 | 37312419 |

| High | oar3_OAR25_36631465 | oar3_OAR25_37179818 | 25 | 7 | 36631465 | 37179818 |

| Low | Chr25:35575408 | Chr25:35687973 | 25 | 5 | 35575408 | 35687973 |

| Low | Chr25:35770158 | Chr25:35919902 | 25 | 8 | 35770158 | 35919907 |

| Low | Chr25:36456595 | Chr25:36800459 | 25 | 11 | 36456595 | 36800459 |

| Low | OAR25_35590985.1 | OAR25_36580394.1 | 25 | 3 | 35590985 | 36580394 |

| Low | oar3_OAR25_35598041 | oar3_OAR25_35873731 | 25 | 5 | 35598041 | 35873731 |

| Method | Gene | Chromosome | Position | Function Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High fecundity | ||||

| FST | CNOT11 | 3 | 100058810 | Pregnancy rate [31]. |

| ATG10 | 5 | 79156925 | Autophagy and innate immune defense [32,33]. | |

| RPS23 | 5 | 79446021 | Protein synthesis and immunity [9]. | |

| ANK2 | 6 | 12314476 | Structure of ovarian granulosa cells [34]. | |

| CAMK2D | 6 | 11870774 | Fat metabolism and meat quality traits [35]. | |

| STK32B | 6 | 103213333 | Fat deposition and marbling [36]. | |

| UGT8 | 6 | 11004274 | Development and function of the nervous and endocrine systems [37]. | |

| ROH | ADIRF | 25 | 41056054 | Adipose deposition tissue [38]. |

| ARHGAP22 | 25 | 42255625 | Fertility traits, lipid metabolism, insulin resistance, and inflammation response [39]. | |

| GHITM | 25 | 38626280 | Metritis and fertility traits [40]. | |

| GLUD1 | 25 | 41085197 | Follicular development and maturation [41]. | |

| GRID1 | 25 | 39879600 | Litter size [42]. | |

| LRIT1 | 25 | 38706733 | Cellular energy [43]. | |

| MAPK8 | 25 | 42210625 | Follicular development [44]. | |

| MMRN2 | 25 | 41018603 | Cell differentiation or organogenesis [45]. | |

| TRNAC-GCA | 25 | 39208014 | Plasma urea concentration and sperm quality [46,47]. | |

| VSTM4 | 25 | 42748968 | Cumulus cells and somatic cell nuclear transfer [48]. | |

| Low fecundity | ||||

| ROH | HERC6 | 6 | 36181502 | Pregnancy rate [49]. |

| CCL28 | 16 | 31346400 | Lymphocyte colonization of fetal tissues [50]. | |

| GHR | 16 | 31832298 | Growth performance, carcass traits, milk traits, and cell differentiation [51]. | |

| HMGCS1 | 16 | 31409821 | Cholesterol biosynthesis [52]. | |

| DPF2 | 21 | 42741418 | Fertility [53]. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Ramos, R.; Trujano-Chavez, M.Z.; Gallegos-Sánchez, J.; Becerril-Pérez, C.M.; Cadena-Villegas, S.; Cortez-Romero, C. Detection of Candidate Genes Associated with Fecundity through Genome-Wide Selection Signatures of Katahdin Ewes. Animals 2023, 13, 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13020272

Sánchez-Ramos R, Trujano-Chavez MZ, Gallegos-Sánchez J, Becerril-Pérez CM, Cadena-Villegas S, Cortez-Romero C. Detection of Candidate Genes Associated with Fecundity through Genome-Wide Selection Signatures of Katahdin Ewes. Animals. 2023; 13(2):272. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13020272

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Ramos, Reyna, Mitzilin Zuleica Trujano-Chavez, Jaime Gallegos-Sánchez, Carlos Miguel Becerril-Pérez, Said Cadena-Villegas, and César Cortez-Romero. 2023. "Detection of Candidate Genes Associated with Fecundity through Genome-Wide Selection Signatures of Katahdin Ewes" Animals 13, no. 2: 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13020272

APA StyleSánchez-Ramos, R., Trujano-Chavez, M. Z., Gallegos-Sánchez, J., Becerril-Pérez, C. M., Cadena-Villegas, S., & Cortez-Romero, C. (2023). Detection of Candidate Genes Associated with Fecundity through Genome-Wide Selection Signatures of Katahdin Ewes. Animals, 13(2), 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13020272