Beliefs and Attitudes of British Residents about the Welfare of Fur-Farmed Species and the Import and Sale of Fur Products in the UK

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

There will be an opportunity for government in the future, once we have left the EU and the nature of our future trading relationship has been established, to consider further steps such as a ban on fur imports or a ban on sales [23].

- What are UK residents’ beliefs about the welfare of fur-farmed and wild-trapped animals?

- What are UK residents’ beliefs about the legal context of the fur trade in the UK?

- What are UK residents’ attitudes toward the import and sale of fur in the UK, and do they support regulation or prohibition?

2. Public Attitudes to Fur in the UK

3. Methodology

3.1. Questionnaire

3.2. Data Cleaning and Analysis

3.3. Limitations of the Study

4. Results

4.1. Beliefs of UK Residents about the Welfare of Fur-Farmed and Wild-Trapped Animals

4.2. Attitudes of UK Residents on the Import and Sale of Fur in the UK

4.2.1. Knowledge about the Sale of Fur Products in the UK

4.2.2. Attitudes to the Sale of Fur in the UK

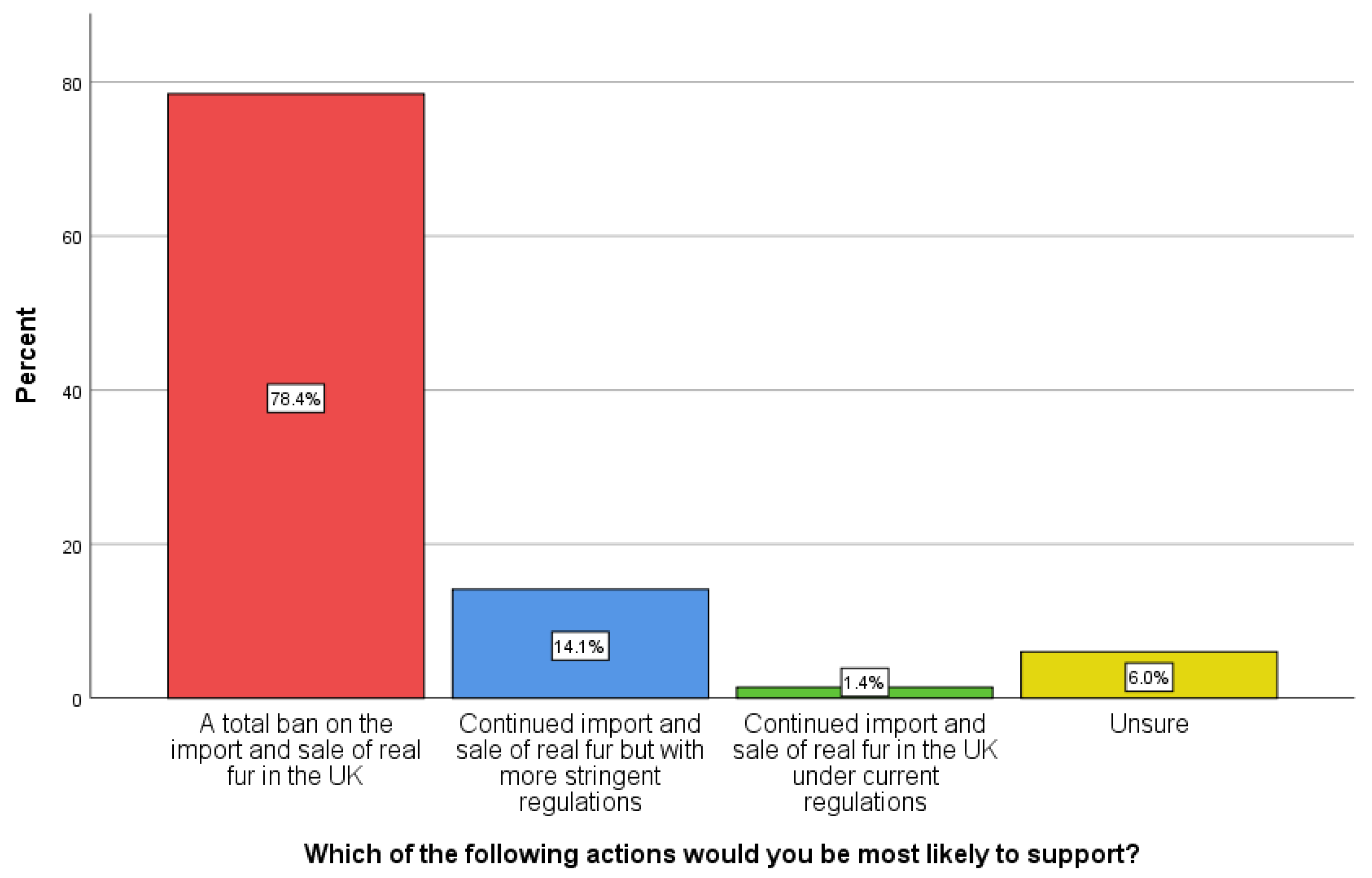

4.3. Do UK Residents Support a Ban on the Import and Sale of Fur in the UK?

5. Discussion

5.1. Beliefs about the Welfare of Animals Killed for Their Fur

5.2. Knowledge about the Sale of Fur Products in the UK

5.3. Attitudes toward Fur and Its Import and Sale within the UK

5.4. Labelling and the Farming of Fur vs. Food and Fur vs. Leather

5.5. Stated Preference and Revealed Preference in the Public Consumption of Fur Products

5.6. Prohibiting the Import and Sale of Fur in the UK Post-Brexit

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wiebers, D.O.; Feigin, V.L. What the COVID-19 crisis is telling humanity. Neuroepidemiology 2020, 1, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irving, A.T.; Ahn, M.; Goh, G.; Anderson, D.E.; Wang, L.-F. Lessons from the host defences of bats, a unique viral reservoir. Nature 2021, 589, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roger, F.; Delabouglise, A.; Roche, B.; Peyre, M.; Chevalier, V. Origin of the COVID-19 Virus: The Trail of Mink Farming. The Conversation. 14 March 2021. Available online: https://theconversation.com/origin-of-the-covid-19-virus-the-trail-of-mink-farming-155989 (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Organisation for Animal Health; World Health Organization. SARS-CoV-2 in Animals Used for Fur Farming; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy; World Organisation for Animal Health: Paris, France; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- The Humane Society of the United States. Ahead of G7 Meeting, President Biden Urged to Support a Permanent, Global End to Fur Farming to Avoid Deadly Future Pandemics. Available online: https://www.humanesociety.org/news/ahead-g7-meeting-president-biden-urged-support-permanent-global-end-fur-farming-avoid-deadly (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- Fur Free Alliance. COVID-19 on Mink Farms. Available online: https://www.furfreealliance.com/covid-19-on-mink-farms/ (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- Fur Free Alliance. Fur Bans. Available online: https://www.furfreealliance.com/fur-bans/ (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Loftus-Farren, Z. Hanging On. Available online: https://www.earthisland.org/journal/index.php/magazine/entry/hanging-on-fur-farm-trapping/ (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- International Fur Federation. Auction Houses: Fur Harvesters. Available online: https://www.wearefur.com/auction-houses/fur-harvesters-auction/ (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- International Fur Federation. More Good4Fur Certified Farms Boosting Fur Farming. Available online: https://www.wearefur.com/more-good4fur-certified-farms-boosting-fur-farming/ (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- International Fur Federation. Sustainable Fur, Farming, Europe Legislation. Available online: https://www.wearefur.com/responsible-fur/farming/fur-farming-europe/ (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Hansen, H. Global Fur Retail Value; Department of Food and Resource Economics, University of Copenhagen: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fur Free Alliance. Public Opposition against Fur Farming. Available online: https://www.furfreealliance.com/public-opinion/ (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Marriot, H. Fur Is out of Favour but Stays in Fashion through Stealth and Wealth. The Guardian, 6 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Givhan, R. Fur Is under Attack. It’s Not Going down without a Fight. The Washington Post, 23 December 2019; 5. [Google Scholar]

- Humane Society International. The Case for a Ban on the UK Fur Trade; Humane Society International: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Scientific Committee on Animal Health and Animal Welfare. The Welfare of Animals Kept for Fur Production; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Littin, K.; Mellor, D. Strategic animal welfare issues: Ethical and animal welfare issues arising from the killing of wildlife for disease control and environmental reasons. Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epizoot. 2005, 24, 767–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iossa, G.; Soulsbury, C.; Harris, S. Mammal trapping: A review of animal welfare standards of killing and restraining traps. Anim. Welf. 2007, 16, 335. [Google Scholar]

- Farm Animal Welfare Council. Farm Animal Welfare Council Disapproves of Mink and Fox Farming; UK Parliament: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch, S.P. Brexit and Animal Welfare Impact Assessment: Analysis of the Opportunities Brexit Presents for Animal Protection in the UK, EU, and Internationally. Animals 2019, 9, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Environment Food and Rural Affairs Committee. Fur Trade in the UK; House of Commons: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Environment Food and Rural Affairs Committee. Fur Trade in the UK: Government Response to the Committee’s Seventh Report; House of Commons: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UK Government and Parliament. Ban the Sale of Animal Fur in the UK. Available online: https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/200888 (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- Department for the Environment Food and Rural Affairs. Action Plan for Animal Welfare. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/action-plan-for-animal-welfare (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- Department for the Environment Food and Rural Affairs. The Fur Market in Great Britain. Available online: https://consult.defra.gov.uk/animal-welfare-in-trade/fur-market-in-great-britain/ (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- Ipsos MORI. Attitudes to Fur in the UK; Ipsos: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- RSPCA. New Survey Shows 93% of People Will Not Wear Fur; Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals: Horsham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. The RSPCA Good Business Awards; Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals: Horsham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- YouGov; Four Paws. Fur in the UK Market; YouGov: London, UK; Four Paws: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- YouGov; Humane Society International UK. YouGov/HSl Results; YouGov: London, UK; Humane Society International: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- YouGov; Humane Society International UK. Survey Results; YouGov: London, UK; Humane Society International: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- YouGov. YouGov/HSI Survey Results; YouGov: London, UK; Humane Society International: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- YouGov. YouGov/Humane Society International UK Survey Results; YouGov: London, UK; Humane Society International: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- YONDER. Fur Trade Survey; YONDER: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, C.J.C.; McCulloch, S. Student attitudes on animal sentience and use of animals in society. J. Biol. Educ. 2005, 40, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, C.; Izmirli, S.; Aldavood, J.; Alonso, M.; Choe, B.; Hanlon, A.; Handziska, A.; Illmann, G.; Keeling, L.; Kennedy, M. An international comparison of female and male students’ attitudes to the use of animals. Animals 2011, 1, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeates, J. Is ’a life worth living’ a concept worth having? Anim. Welf. 2011, 20, 397–406. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett, H.; Harris, S. The Case Against Fur Factory Farming: A Scientific Review of Animal Welfare Standards and ‘WelFur’; Respect for Animals: Nottingham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, B. Mike Ashley’s House of Fraser Removes Fur Products after Customer Backlash. Independent, 22 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Anon. House of Fraser: ‘House of Horror’ for Reversing Fur Ban, Says Charity. BBC News. 20 November 2019. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/newsbeat-50488274 (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- Deckha, M. Disturbing images: PETA and the feminist ethics of animal advocacy. Ethics Environ. 2008, 13, 35–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugo, K. Monster Foxes Caught on Camera at Fur Farms. Newsweek, 21 September 2017; 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mace, J.L.; McCulloch, S.P. Yoga, Ahimsa and Consuming Animals: UK Yoga Teachers’ Beliefs about Farmed Animals and Attitudes to Plant-Based Diets. Animals 2020, 10, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Piazza, J. Why people love animals yet continue to eat them. In Why We Love and Exploit Animals: Bridging Insights from Academia and Advocacy; Dhont, K., Hodson, G., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, M. Animal Welfare Law in Britain: Regulation and Responsibility; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fur Free Alliance. Certified Cruel: Why WelFur Fails to Stop the Suffering of Animals on Fur Farms; Fur Free Alliance: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, A. Tamed: Ten Species That Changed Our World; Random House: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Siegle, L. Is It Time to Give up Leather? The Observer, 13 March 2016; 4. [Google Scholar]

- Norwood, F.B.; Tonsor, G.; Lusk, J.L. I will give you my vote but not my money: Preferences for public versus private action in addressing social issues. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2019, 41, 96–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehleke, R.; Hüttel, S. The free-rider deficit in the demand for farm animal welfare-labelled meat. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2019, 46, 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, G.; Imai, K.; Zhou, Y.-Y. Design and analysis of the randomized response technique. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2015, 110, 1304–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, M.G.; Pieters, R.; Fox, J.-P. Reducing social desirability bias through item randomized response: An application to measure underreported desires. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 47, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Source | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1997 | Ipsos MORI poll (commissioned by Marie Claire and the RSPCA) [27] | Survey of 1946 adults (aged 15+ in 173 sampling points throughout Great Britain in June 1997. Interviews were conducted face-to-face in-home): 87% of adults would never wear real fur. Of these, 73% thought it was wrong or disapproved, 12% said it was too expensive, 8% cited it as unfashionable and 6% thought other people would disapprove. |

| 2007 | RSPCA poll [28] | 93% of British adults refused to wear real fur; 43% checked labels to see if the fur was real or fake; 92% believed fur should be labelled as real or fake; 91% would not buy fur even if it was cheap; 61% thought celebrities should not wear real fur; 61% thought there was a moral difference between animals farmed for meat and animals raised for fur. |

| 2010 | TNS PhoneBus poll (commissioned by RSPCA) [29] | A TNS opinion poll was conducted in Great Britain via TNS PhoneBus, a telephone Omnibus survey. A representative sample of 2004 adults aged 16 and above were interviewed in September and October 2010. 95% refused to wear real fur and 93% thought products should be clearly labelled as real or fake fur. |

| 2014 | YouGov poll (commissioned by FOUR PAWS) [30] | Survey of 2081 individuals (aged ≥18). Fieldwork was conducted online in January 2014. The figures were weighted to be representative of all UK adults (aged 18+). 62% of the UK population preferred to buy from retailers that did not sell animal fur products. 74% of the interviewed individuals thought that using animals to produce fur for the fashion industry was wrong. |

| 2016 | YouGov poll (commissioned by HSI UK) [31] | Survey of 2051 individuals (aged ≥18). <10% felt it was acceptable to be able to buy and sell products containing domestic dog fur (7%), seal fur (8%) or cat fur (9%). Between 8% and 12% felt it was acceptable to be able to buy and sell products containing fur from: foxes (12%), mink (12%), chinchillas (9%), raccoon dogs (8%) and coyotes (8%). 20% felt it was acceptable to be able to buy and sell products containing rabbit fur. |

| 2018 | YouGov poll (commissioned by HSI UK) [32] | “To what extent, if at all, would you support or oppose a ban on the import and sale of all animal fur in the UK?” Survey of 1594 people, conducted online in February 2018. The figures were weighted to be representative of all GB adults (aged 18+). 69% of the British public strongly supported (46%) or tended to support (23%) a ban. 8% opposed a ban, composed of 3% who strongly opposed it and 5% who tended to oppose it. 18% stated they would neither support nor oppose a ban, and the remaining 6% did not know. |

| 2020 | YouGov poll (commissioned by HSI UK) [33] | “To what extent, if at all, would you support or oppose a ban on the import and sale of animal fur in the UK?” Survey of 1682 people, conducted online in 2020. The figures were weighted to be representative of all GB adults (aged 18+). 72% of the British public strongly supported (52%) or tended to support (21%) a ban. 16% were opposed, composed of 8% who strongly opposed it and 8% who tended to oppose it. 12% did not know. “Do you wear, or have you ever worn, real animal fur?” A total of 93% of those polled either had never worn fur or no longer wore it (10% had worn real fur in the past but no longer did so, while 83% did not wear fur and never had); 3% currently wore real fur; 5% did not know. |

| 2021 | YouGov poll (commissioned by HSI UK) [34] | Survey of 1647 people, conducted in 2021. 93% considered it unacceptable to keep foxes for their whole lives in wire cages measuring 1–1.5 m2. 92% considered it unacceptable to trap wild animals (e.g., coyotes) in leg-hold traps. 92% considered it unacceptable to kill foxes by anal/vaginal electrocution. |

| 2021 | YONDER poll (commissioned by HSI UK) [35] | “To what extent, if at all, would you support or oppose a ban on the import and sale of animal fur in the UK?” Survey of 2026 people, conducted in 2021. 72% of the British public strongly supported (52%) or tended to support (20%) a ban. 12% were opposed, composed of 7% who strongly opposed it and 4% who tended to oppose it. |

| Section | Questions’ Wording | Response Type/Measurement Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Section 2—Beliefs about the welfare of animals killed for their fur | I believe animals on fur farms generally have a life worth living | Likert scale: strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree |

| I believe animals on fur farms generally have a good life | ||

| I believe animals farmed for their fur are killed humanely | ||

| I believe animal welfare standards on fur farms are well-regulated | ||

| I believe fur farms can meet the welfare needs of species such as the mink and fox | ||

| I believe cages provide fur farm species such as the mink and fox with a good level of welfare | ||

| I believe leg-hold traps used to catch wild species such as the coyote and lynx do not cause suffering | ||

| I believe animals caught in traps in the wild are killed humanely | ||

| Section 3—Attitudes toward buying fur and the import and sale of fur in the UK | Are you aware that farming animals for their fur is banned in the UK? | Yes/no |

| Are you aware that fur from farmed species is imported and sold in the UK? | ||

| Are you aware that fur from wild-caught species is imported and sold in the UK? | ||

| In the past five years, have you knowingly purchased any products made from real fur? | ||

| If you purchased a product made of fur, did you consider any of the following? (Country of origin of the product; Species of animal used to make the product; Whether the animal was farmed or wild-caught; N/A—I did not purchase a real fur product) | Multiple choice, four response options | |

| If you have purchased fur, please state your reasons for doing so? | Open-text response | |

| If you were to purchase a fur product, which of the following would be the most important to you? (Country of origin of the product; Species of animal used to make the product; Whether the animal had received a good level of welfare; Whether the animal was killed humanely; Whether the animal was farmed or wild-caught; N/A—I would not purchase a fur product) | Multiple choice, six response options | |

| I believe all fur products should be labelled as ‘real’ or ‘synthetic’ | Likert scale: strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree | |

| I approve of retailers that sell real fur | ||

| Buying real fur is morally acceptable | ||

| There is no moral difference between farming animals such as pigs and chickens for meat and farming animals such as mink and foxes for fur | ||

| There is no moral difference between wearing real fur and wearing leather | ||

| It is morally acceptable for the UK government to ban fur farming and continue to import and sell fur from producers overseas | ||

| I oppose the use of real fur regardless of the welfare schemes implemented by the fur trade | ||

| I oppose the use of real fur regardless of the species used | ||

| Farming and killing animals for commercial use in fashion is wrong | ||

| Trapping and killing wild animals for commercial use in fashion is wrong | ||

| No regulatory changes to animal welfare standards could provide animals farmed for their fur with ‘a life worth living’ | ||

| Which of the following actions would you be most likely to support? (A total ban on the importation and sale of real fur in the UK; Continued importation and sale of real fur but with more stringent regulations; Continued importation and sale of real fur in the UK under current regulations; Unsure). | Multiple choice, four response options |

| Q | Statement | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Chi-Squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | I believe animals on fur farms generally have a life worth living | 12.7% (39) | 8.1% (25) | 6.8% (21) | 17.9% (55) | 54.4% (167) | 0.000 (241.1, 4, 305) |

| 20.8% (64) | 72.3% (222) | ||||||

| 12 | I believe animals on fur farms generally have a good life | 1% (3) | 3.3% (10) | 7.2% (22) | 22.5% (69) | 66.1% (203) | 0.000 (456.0, 4, 305) |

| 4.3% (13) | 88.6% (272) | ||||||

| 13 | I believe animals farmed for their fur are killed humanely | 2.3% (7) | 7.2% (22) | 12.7% (39) | 25.7% (79) | 52.1% (160) | 0.000 (247.9, 4, 305) |

| 9.5% (29) | 77.8% (239) | ||||||

| 14 | I believe animal welfare standards on fur farms are well-regulated | 1% (3) | 5.2% (16) | 18.6% (57) | 25.4% (78) | 49.8% (153) | 0.000 (233.5, 4, 305) |

| 6.2% (19) | 75.2% (231) | ||||||

| 15 | I believe fur farms can meet the welfare needs of species such as the mink and fox | 1.6% (5) | 4.9% (15) | 11.4% (35) | 27.7% (85) | 54.4% (167) | 0.000 (291.9, 4, 305) |

| 6.5% (20) | 82.1% (252) | ||||||

| 16 | I believe cages provide fur farm species such as the mink and fox with a good level of welfare | 0.3% (1) | 1.6% (5) | 7.2% (22) | 21.2% (65) | 69.7% (214) | 0.000 (520.6, 4, 305) |

| 1.9% (6) | 90.9% (279) | ||||||

| 17 | I believe leg-hold traps used to catch wild species such as the coyote and lynx do not cause suffering | 0.3% (1) | 1% (3) | 2.3% (7) | 14% (43) | 82.4% (254) | 0.000 (558.4, 3, 305) |

| 1.3% (4) | 96.4% (297) | ||||||

| 18 | I believe animals caught in traps in the wild are killed humanely | 1.3% (4) | 2.3% (7) | 5.2% (16) | 17.9% (55) | 73.3% (225) | 0.000 (577.9, 4, 305) |

| 3.6% (11) | 91.2% (280) | ||||||

| Question | Yes | No | Chi-Squared |

|---|---|---|---|

| Are you aware that farming animals for their fur is banned in the UK? | 59.6% (168) | 40.4% (114) | 0.001 (10.7, 1, 283) |

| Are you aware that fur from farmed species is imported and sold in the UK? | 80.5% (227) | 19.5% (55) | 0.000 (105.8, 1, 283) |

| Are you aware that fur from wild-caught species is imported and sold in the UK? | 66.7% (188) | 33.3% (94) | 0.000 (31.9, 1, 283) |

| In the past five years, have you knowingly purchased any products made from real animal fur? (This includes accessories or garments with fur trimmings.) | 7.8% (22) | 92.2% (260) | 0.000 (201.8, 1, 283) |

| Question | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Chi-Squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26. I believe all fur products should be labelled as ‘real’ or ‘synthetic’ | 77.8% (221) | 18% (51) | 1.8% (5) | 0.7% (2) | 1.4% (4) | 0.000 (626.7, 4, 283) |

| 95.8% (272) | 2.1% (6) | |||||

| 27. I approve of retailers that sell real fur | 2.1% (6) | 2.8% (8) | 14.8% (42) | 17.3% (49) | 62.7% (178) | 0.000 (352.1, 4, 283) |

| 4.9% (14) | 80% (227) | |||||

| 28. Buying real fur is morally acceptable | 2.1% (6) | 5.3% (15) | 14.8% (42) | 15.1% (43) | 62.3% (177) | 0.000 (339.0, 4, 283) |

| 7.4% (21) | 77.4% (220) | |||||

| 29. There is no moral difference between farming animals such as pigs and chickens for meat and farming animals such as mink and foxes for fur | 16.5% (47) | 19.4% (55) | 11.3% (32) | 26.1% (74) | 26.4% (75) | 0.000 (23.7, 4, 283) |

| 35.9% (102) | 52.5% (149) | |||||

| 30. There is no moral difference between wearing real fur and wearing leather | 17.6% (50) | 17.3% (49) | 19% (54) | 31% (88) | 14.8% (42) | 0.000 (23.1, 4, 283) |

| 34.9% (99) | 45.8% (130) | |||||

| 31. It is morally acceptable for the UK government to ban fur farming and continue to import and sell fur from producers overseas | 2.1% (6) | 3.9% (11) | 10.2% (29) | 30.6% (87) | 52.8% (150) | 0.000 (265.9, 4, 283) |

| 6% (17) | 83.4% (237) | |||||

| 32. I oppose the use of real fur regardless of the welfare schemes implemented by the fur trade | 54.9% (156) | 20.1% (57) | 9.9% (28) | 9.5% (27) | 5.3% (15) | 0.000 (235.1, 4, 283) |

| 75% (213) | 14.8% (42) | |||||

| 33. I oppose the use of real fur regardless of the species used | 58.1% (165) | 19.7% (56) | 8.5% (24) | 8.8% (25) | 4.6% (13) | 0.000 (277.6, 4, 283) |

| 77.8% (221) | 13.4% (38) | |||||

| 34. Farming and killing animals for commercial use in fashion is wrong | 66.5% (189) | 16.9% (48) | 9.9% (28) | 4.9% (14) | 1.4% (4) | 0.000 (406.4, 4, 283) |

| 83.4% (237) | 6.3% (18) | |||||

| 35. Trapping and killing wild animals for commercial use in fashion is wrong | 75.4% (214) | 16.2% (46) | 5.3% (15) | 1.8% (5) | 1.1% (3) | 0.000 (568.1, 4, 283) |

| 91.6% (260) | 2.9% (8) | |||||

| 36. No regulatory changes to animal welfare standards could provide animals farmed for their fur with ‘a life worth living’ | 51.8% (147) | 22.2% (63) | 11.6% (33) | 9.9% (28) | 4.2% (12) | 0.000 (204.5, 4, 283) |

| 74% (210) | 14.1% (40) | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Halliday, C.; McCulloch, S.P. Beliefs and Attitudes of British Residents about the Welfare of Fur-Farmed Species and the Import and Sale of Fur Products in the UK. Animals 2022, 12, 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12050538

Halliday C, McCulloch SP. Beliefs and Attitudes of British Residents about the Welfare of Fur-Farmed Species and the Import and Sale of Fur Products in the UK. Animals. 2022; 12(5):538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12050538

Chicago/Turabian StyleHalliday, Carly, and Steven P. McCulloch. 2022. "Beliefs and Attitudes of British Residents about the Welfare of Fur-Farmed Species and the Import and Sale of Fur Products in the UK" Animals 12, no. 5: 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12050538

APA StyleHalliday, C., & McCulloch, S. P. (2022). Beliefs and Attitudes of British Residents about the Welfare of Fur-Farmed Species and the Import and Sale of Fur Products in the UK. Animals, 12(5), 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12050538