The Role of Dogs in the Relationship between Telework and Performance via Affect: A Moderated Moderated Mediation Analysis

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

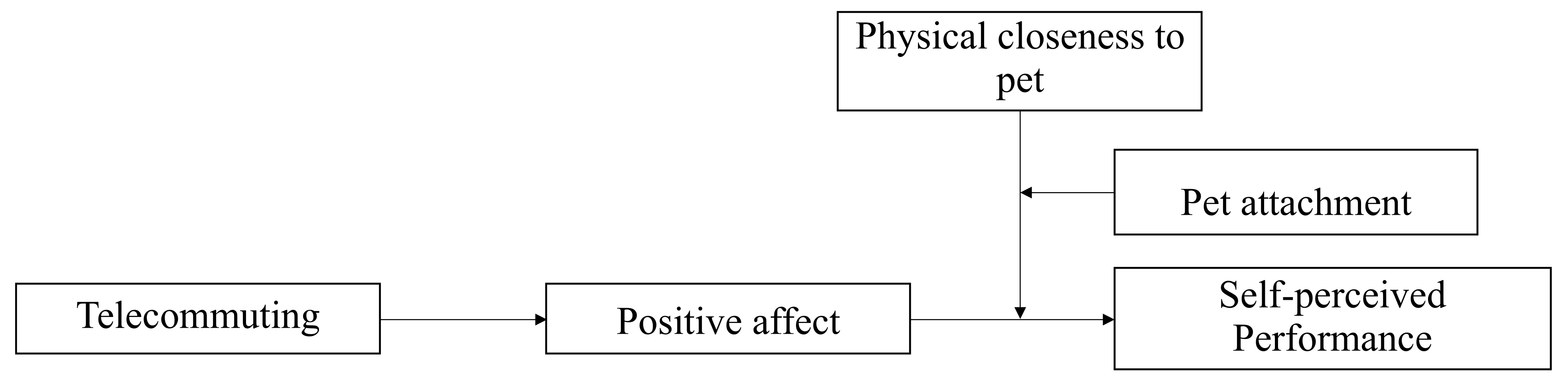

2. The Relationship between Telework, Positive Affect, and Performance

3. The Moderating Role of Pet Attachment and Physical Closeness

4. Method

4.1. Participants and Procedure

4.1.1. The Group without Pets

4.1.2. The Group with Pets

4.2. Measures

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

5.2. Means Comparison between Groups

5.3. Hypotheses Testing

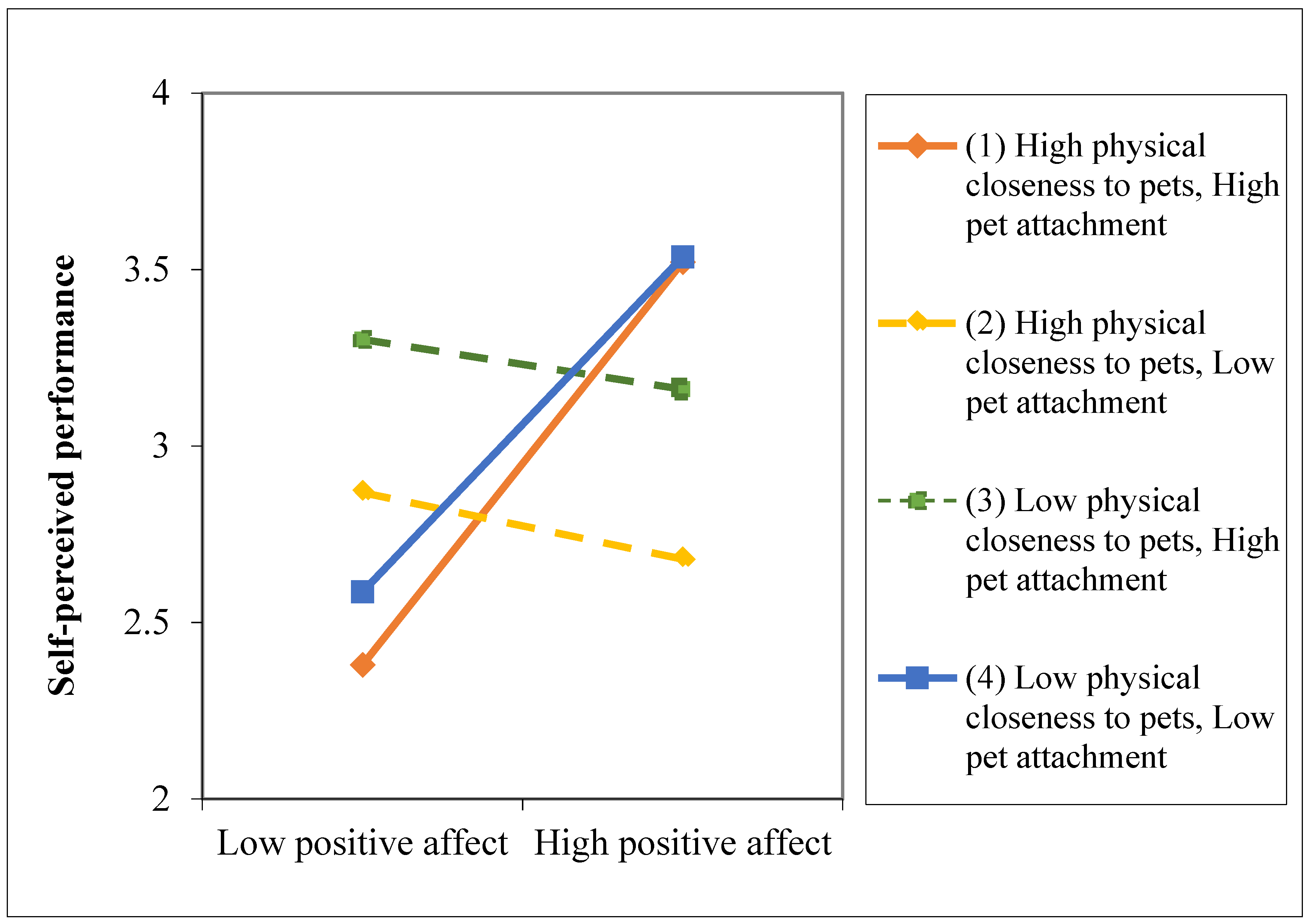

6. Discussion

6.1. Limitations and Future Research

6.2. Practical Contributions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Survey

Appendix A.1.1. The Attitude toward Telework

Appendix A.1.2. Effectiveness/Productivity

- When e-working I can concentrate better on my work tasks.

- E-working makes me more effective to deliver against my key objectives and deliverables.

- If I am interrupted by family/other responsibilities whilst e-working from home, I still meet my line manager‘s quality expectations.

- My overall job productivity has increased by my ability to e-work remotely/from home.

Appendix A.1.3. Organizational Trust

- My organisation provides training in e-working skills and behaviours.

- I trust my organisation to provide good e-working facilities to allow me to e-work effectively.

- My organisation trusts me to be effective in my role when I e-work remotely.

Appendix A.1.4. Interference between Personal and Work-Life

- My social life is not poor when e-working remotely.

- My e-working does not take up time that I would like to spend with my family/friends or on other non-work activities.

- When e-working remotely I do not often think about work related problems outside of my normal working hours.

- I am happy with my work-life balance when e-working remotely.

- Constant access to work through e-working is not very tiring.

- I do not feel that work demands are much higher when I am e-working remotely.

- When e-working from home I do not know when to switch off/put work down so that I can rest (R).

Appendix A.1.5. Flexibility

- My work is so flexible I could easily take time off e-working remotely, if and when I want to.

- My line manager allows me to flex my hours to meet my needs, providing all the work is completed.

- My supervisor gives me total control over when and how I get my work completed when e-working.

- Scale (1—totally disagree; 5—totally agree)

Appendix A.1.6. Positive Affect

- Enthusiastic.

- Calm.

- Joyful.

- Relaxed.

- Inspired.

- Laid-back.

- Excited.

- At ease.

Appendix A.1.7. Self-Reported Job Performance

- Today, I achieved my job goals.

- Today I made the right decisions.

- Today I permed without mistakes.

- Today I handled the responsibilities and daily demands of my work.

- Today I get the things done.

- Today I get along with others at work.

Appendix A.1.8. Emotional Attachment to Pets

- My pet knows when I’m feeling bad.

- I often talk to other people about my pet.

- My pet understands me.

- I believe that loving my pet helps me stay healthy.

- My pet and I have a very close relationship.

- I play with my pet quite often.

- I consider my pet to be a great companion.

- My pet makes me feel happy.

- I am not very attached to my pet (R).

- Owning a pet adds to my happiness.

- I consider my pet to be a friend.

Appendix A.1.9. Physical Closeness to Pets

- In telework, I usually take breaks to interact with my pet.

- While you work from home, my pet is close to me when I am working.

- During telework, my pet is not close to me while I work (R).

- While I am working, I use to interact with my pet.

References

- Wagner, E.; Pina e Cunha, M. Dogs at the Workplace: A Multiple Case Study. Animals 2021, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.P.; Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources theory: Its implication for stress, health, and resilience. In The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping; Folkman, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Kurland, N.B.; Bailey, D.E. When workers are here, there, and everywhere: A discussion of the advantages and challenges of telework. Organ. Dyn. 1999, 28, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Elst, T.; Verhoogen, R.; Sercu, M.; Van den Broeck, A.; Baillien, E.; Godderis, L. Not extent of telecommuting, but job characteristics as proximal predictors of work-related well-being. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 59, e180–e186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blau, P. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Lemos, A.; Wulf, G.; Lewthwaite, R.; Chiviacowsky, S. Autonomy support enhances performance expectancies, positive affect, and motor learning. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2017, 31, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, T.K.; Matthews, S.H.; Wan, M.; Zhang, Y. The secret life of pets: The intersection of animals and organizational life. J. Organ. Behav. 2020, 41, 694–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzer, M.M. Managing from afar: Performance and rewards in a telecommuting environment. Compens. Benefits Rev. 1997, 29, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonner, K.L.; Roloff, M.E. Why teleworkers are more satisfied with their jobs than are office-based workers: When less contact is beneficial. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2010, 38, 336–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnavita, N.; Tripepi, G.; Chiorri, C. Telecommuting, off-time work, and intrusive leadership in workers’ well-being. Int Journ Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molla, R. How Remote Work is Quietly Remaking Our Lives. 9 October 2019. Available online: https://www.vox.com/recode/2019/10/9/20885699/remote-work-from-anywhere-change-coworking-office-real-estate (accessed on 29 May 2022).

- Gajendran, R.S.; Harrison, D.A. The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fredrickson, B.L. What good are positive emotions? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 300–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fredrickson, B.L. Positive emotions broaden and build. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; Volume 47, pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A. Environmentally induced positive affect: Its impact on self-efficacy, task performance, negotiation, and conflict. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 20, 368–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, J.E.; Glomb, T.M.; Shen, W.; Kim, E.; Koch, A.J. Building positive resources: Effects of positive events and positive reflection on work stress and health. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1601–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avey, J.B.; Reichard, R.J.; Luthans, F.; Mhatre, K.H. Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2011, 22, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Motowildo, S.J.; Borman, W.C.; Schmit, M.J. A theory of individual differences in task and contextual performance. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotson, M.J.; Hyatt, E.M. Understanding dog–human companionship. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brickel, C.M. 18/Pet Facilitated Therapies: A Review of the Literature and Clinical Implementation Considerations. Clin. Gerontol. 1986, 5, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, J.W.S. Social Interactions Between Animals and People—A New Biological Framework; Anthrozoology Institute, University of Southampton: Southampton, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cusack, O. Pets and Mental Health; Haworth: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, B.M.; Úbeda, M.R. Psicoterapia Infantil Asistida por Animales; Fundación Affinity: Barcelona, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nebbe, L. Nature Therapy. In Handbook on Animal Assisted and Therapy: Theoretical Foundations and Guidelines for Practice; Fine, A., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 385–414. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, D.W.; Bergeron, G.; Bourassa, M.W.; Dickson, J.; Gomes, F.; Howe, A.; Kahn, L.H.; Morley, P.S.; Scott, H.M.; Wittum, T.E. Complexities in understanding antimicrobial resistance across domesticated animal, human, and environmental systems. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019, 1441, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, J. The Animals Among Us: How Pets Make Us Human; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, H. Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat; Tantor Audio: Old Saybrook, CT, USA; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- O’Haire, M. Companion animals and human health: Benefits, challenges, and the road ahead. J. Vet. Behav. 2010, 5, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.P. Can pets function as family members? West. J. Nurs. Res. 2002, 24, 621–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colarelli, S.M.; McDonald, A.M.; Christensen, M.S.; Honts, C. A companion dog increases prosocial behavior in work groups. Anthrozoös 2017, 30, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina e Cunha, M.; Rego, A.; Munro, I. Dogs in organizations. Hum. Relat. 2019, 72, 778–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.S.; Mills, D.S. Taking dogs into the office: A novel strategy for promoting work engagement, commitment and quality of life. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harter, S. The development of self-representations during childhood and adolescence. In Handbook of Self and Identity; Leary, M.R., Tangey, J.P., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 610–642. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, A.R.; Strain, L.M.; Brown, C.M.; Rydell, R.J. The simple life: On the benefits of low self-complexity. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 35, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junça-Silva, A.; Lopes, C. Cognitive and affective predictors of occupational stress and job performance: The role of perceived organizational support and work engagement. J. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2021; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, N.; Dorigatti, I.; Cori, A.; Riley, S.; Ferguson, N.M. Estimating the Potential Total Number of Novel Coronavirus Cases in Wuhan City, China. 2020. Available online: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/mrc-gida/2020-01-17-COVID19-Report-1.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Sohrabi, C.; Alsafi, Z.; O’neill, N.; Khan, M.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, R. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int. J. Surg. 2020, 76, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, C.A.; Wallace, L.M.; Spurgeon, P.C.; Tramontano, C.; Charalampous, M. Construction and initial validation of the E-Work Life Scale to measure remote e-working. Empl. Relat. 2019, 41, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Warr, P.; Bindl, U.K.; Parker, S.K.; Inceoglu, I. Four-quadrant investigation of job-related affects and behaviours. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2014, 23, 342–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abramis, D.J. Relationship of job stressors to job performance: Linear or an inverted-U? Psychol. Rep. 1994, 75, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, T.P.; Garrity, T.F.; Stallones, L. Psychometric evaluation of the Lexington attachment to pets scale (LAPS). Anthrozoös 1992, 5, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P. A tutorial on the causes, consequences, and remedies of common method biases. MIS Q. 2017, 35, 293–334. [Google Scholar]

- Martela, F.; Ryan, R.M.; Steger, M.F. Meaningfulness as satisfaction of autonomy, competence, relatedness, and beneficence: Comparing the four satisfactions and positive affect as predictors of meaning in life. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 19, 1261–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Development of the job diagnostic survey. J. Appl. Psychol. 1975, 60, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siruri, M.M.; Cheche, S. Revisiting the Hackman and Oldham Job Characteristics Model and Herzberg‘s Two Factor Theory: Propositions on How to Make Job Enrichment Effective in Today‘s Organizations. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2021, 6, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.J.; Kaplan, S.A.; Vega, R.P. The impact of telework on emotional experience: When, and for whom, does telework improve daily affective well-being? Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2015, 24, 882–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Hadi, S.; Bakker, A.B.; Häusser, J.A. The role of leisure crafting for emotional exhaustion in telework during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anxiety, Stress Coping 2021, 34, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, S.B.; Rasmussen, K.G.; Best, A.M. Effect of aquariums on electroconvulsive therapy patients. Anthrozoös 2003, 16, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, N.R.; Fine, A.H.; Schuck, S. Animals in educational settings: Research and practice. In Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Volume 1. Attachment; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Volume 2. Separation: Anxiety and Anger; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Volume 3. Loss: Sadness and Depression; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Antonacopoulos, N.M.; Pychyl, T.A. An examination of the potential role of pet ownership, human social support and pet attachment in the psychological health of individuals living alone. Anthrozoös 2010, 23, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stoermer, S.; Lauring, J.; Selmer, J. The effects of positive affectivity on expatriate creativity and perceived performance: What is the role of perceived cultural novelty? Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2020, 79, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lades, L.K.; Laffan, K.; Daly, M.; Delaney, L. Daily emotional well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 902–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Landry, C.A.; Paluszek, M.M.; Asmundson, G.J. Reactions to COVID-19: Differential predictors of distress, avoidance, and disregard for social distancing. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F.P.; Humphrey, S.E. The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Junça-Silva, A.; Pombeira, C.; Caetano, A. Testing the affective events theory: The mediating role of affect and the moderating role of mindfulness. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AFP-JIJI. To Reduce Work Stress, Japan Firms Turn to Office Cats, Dogs and Goats. The Japanese Times. 2017. Available online: http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2017/05/25/national/reduce-work-stresse-japan-firms-turn-office-cats-dogs-goats/#.WTQbyuvyvIU (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Johnson, Y. A Pet-Friendly Workplace Policy to Enhance the Outcomes of an Employee Assistance Programme (EAP). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, C.; Verreynne, M.L.; Pachana, N.; Harpur, P. The impact of disability-assistance animals on the psychological health of workplaces: A systematic review. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2019, 29, 400–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Telework | 3.20 1 | 0.51 | - | ||||||

| 2. Positive affect | 3.11 1 | 0.69 | 0.50 ** | - | |||||

| 3. Self-reported job performance | 4.05 1 | 0.54 | 0.31 ** | 0.37 ** | - | ||||

| 4. Pet closeness | 2.63 1 | 1.29 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.07 | - | |||

| 5. Pet attachment | 3.78 1 | 0.99 | −0.06 | −0.06 | 0.17 ** | 0.69 ** | - | ||

| 6. Sex | - | - | 0.01 | 0.13 ** | −0.01 | −0.20 ** | −0.18 ** | - | |

| 7. Age | 31.87 | 9.50 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.14** | −0.07 | −0.12 * | 0.12 * | - |

| Groups | Pet-Owners | Non-Pet Owners | F |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Perceived telework effects | 3.30 (0.46) | 3.20 (0.45) | 4.80 *** |

| Positive affect | 3.21 (0.54) | 3.11 (0.73) | 4.27 ** |

| Performance | 4.10 (0.55) | 3.98 (0.45) | 3.39 * |

| Model | Positive Affect (M) | Self-Reported Performance (Y) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | B | SE | T | |

| Telework (X) | 0.67 ** | 0.07 | 10.07 | 0.18 ** | 0.06 | 2.92 |

| PA (M) | - | - | - | 0.22 ** | 0.05 | 4.75 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.89 | 0.01 * | 0.00 | 2.30 |

| Sex | 0.17 * | 0.07 | 2.48 | −0.07 | 0.06 | −1.21 |

| Indirect Effect | Effect (γ) | BootSE | LLCI-ULCI | |||

| PA | 0.15 | 0.04 | [0.08, 0.22] | |||

| Model | Positive Affect (M) | Self-Reported Performance (Y) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | T | B | SE | t | |

| Telework (X) | 0.66 ** | 0.07 | 10.07 | 0.24 ** | 0.06 | 3.31 |

| PA (M) | - | - | - | 0.13 * | 0.06 | 2.16 |

| Pet closeness (Mod) | - | - | - | −0.19 * | 0.08 | −2.48 |

| Pet attachment (Mod) | - | - | - | 0.19 ** | 0.04 | 4.57 |

| PA * Pet attachment * Pet closeness | - | - | - | 0.39 ** | 0.12 | 2.46 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.89 | 0.01 * | 0.00 | 2.77 |

| Sex | 0.17 * | 0.07 | 2.48 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.43 |

| Index of mod-mod-med effect | Effect (γ) | BootSE | LLCI-ULCI | |||

| PA | 0.26 | 0.14 | [0.02, 0.52] | |||

| R2 = 0.26 F(11,308) = 10.45, p = 0.00, ΔR2 = 0.02, p = 0.01 | ||||||

Publisher‘s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Junça-Silva, A.; Almeida, M.; Gomes, C. The Role of Dogs in the Relationship between Telework and Performance via Affect: A Moderated Moderated Mediation Analysis. Animals 2022, 12, 1727. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12131727

Junça-Silva A, Almeida M, Gomes C. The Role of Dogs in the Relationship between Telework and Performance via Affect: A Moderated Moderated Mediation Analysis. Animals. 2022; 12(13):1727. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12131727

Chicago/Turabian StyleJunça-Silva, Ana, Margarida Almeida, and Catarina Gomes. 2022. "The Role of Dogs in the Relationship between Telework and Performance via Affect: A Moderated Moderated Mediation Analysis" Animals 12, no. 13: 1727. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12131727

APA StyleJunça-Silva, A., Almeida, M., & Gomes, C. (2022). The Role of Dogs in the Relationship between Telework and Performance via Affect: A Moderated Moderated Mediation Analysis. Animals, 12(13), 1727. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12131727