The Research of Standardized Protocols for Dog Involvement in Animal-Assisted Therapy: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

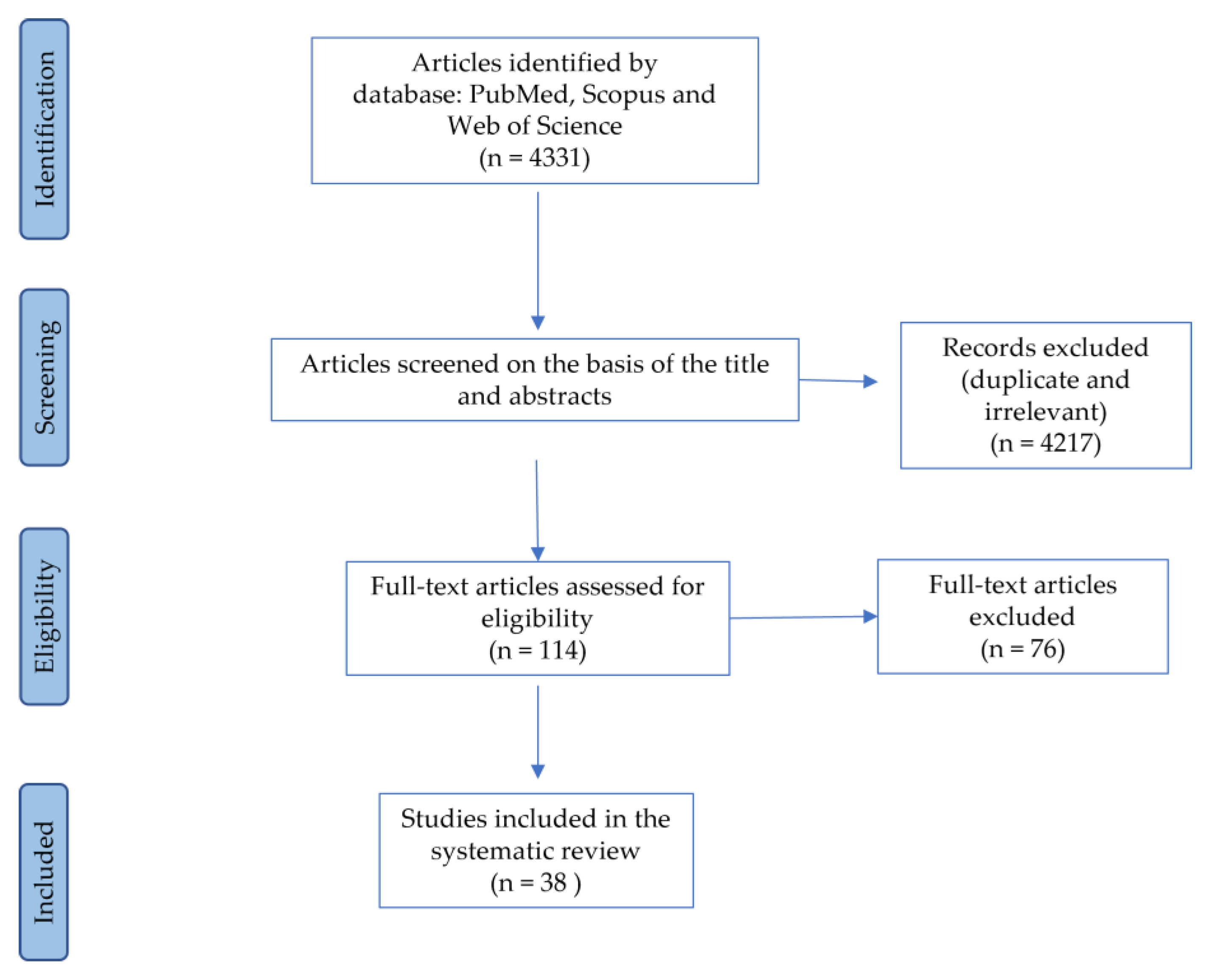

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy and Data Sources

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

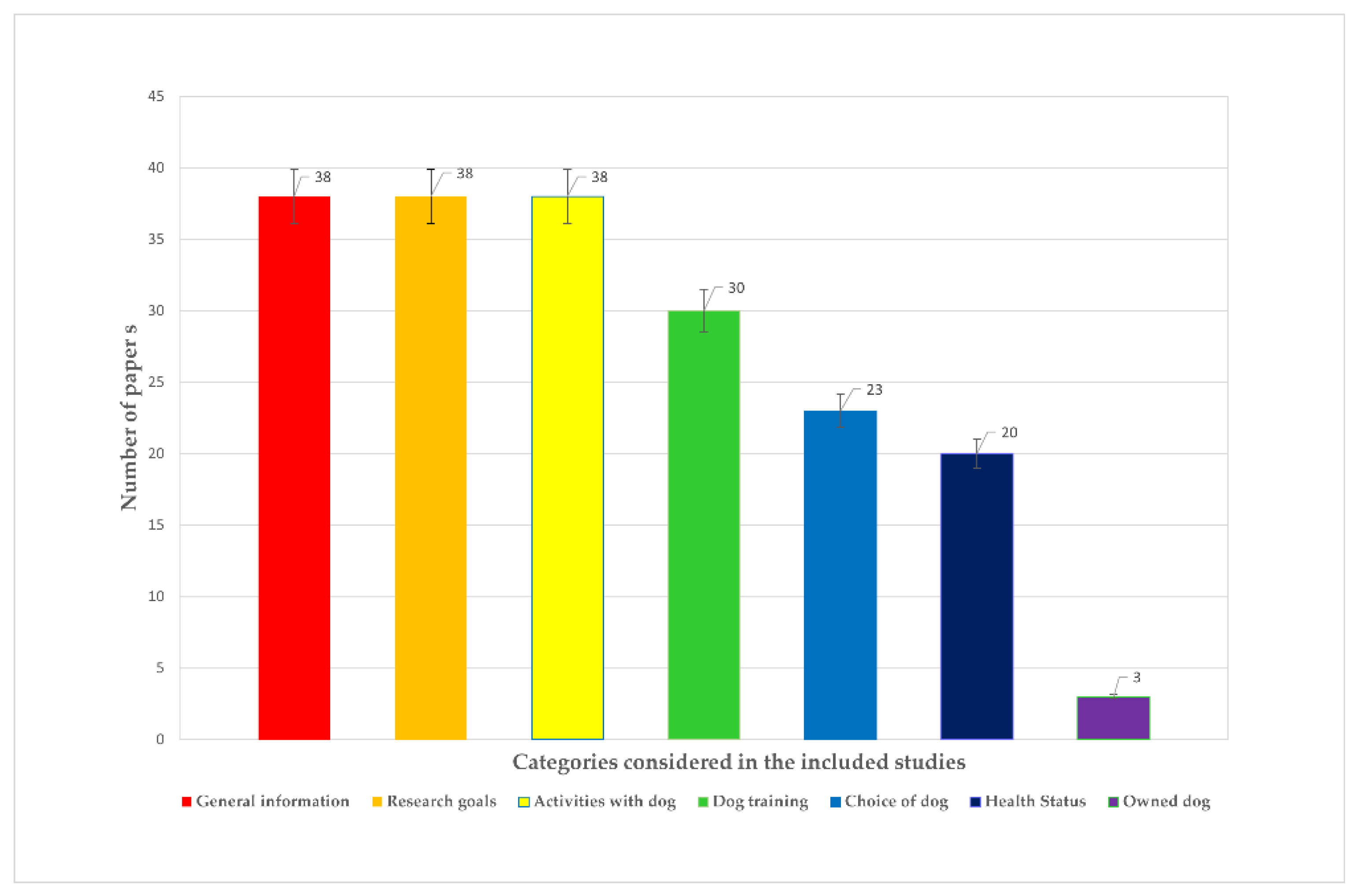

3. Results

3.1. General Information on Dogs

3.2. Research Goals and Activities with Dog

3.3. Methods for Choosing the Dog, Dog Temperament, Dog Training, and Health Status (i.e., Behavioral Veterinary Medical Examination and Health Protocols) of Dogs

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, G.-D.; Zhai, W.; Yang, H.-C.; Wang, L.; Zhong, L.; Liu, Y.-H.; Fan, R.-X.; Yin, T.-T.; Zhu, C.-L.; Poyarkov, A.D.; et al. Out of southern East Asia: The natural history of domestic dogs across the world. Cell Res. 2015, 26, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, J.A. Commensalism or Cross-Species Adoption? A Critical Review of Theories of Wolf Domestication. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hare, B.; Brown, M.; Williamson, C.; Tomasello, M. The Domestication of Social Cognition in Dogs. Science 2002, 298, 1634–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Topál, J.; Gergely, G.; Erdőhegyi, A.; Csibra, G.; Miklosi, A. Differential Sensitivity to Human Communication in Dogs, Wolves, and Human Infants. Science 2009, 325, 1269–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Miklósi, A.; Topál, J. What does it take to become ‘best friends’? Evolutionary changes in canine social competence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2013, 17, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, B.; Tomasello, M. Human-like social skills in dogs? Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005, 9, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagasawa, M.; Murai, K.; Mogi, K.; Kikusui, T. Dogs can discriminate human smiling faces from blank expressions. Anim. Cogn. 2011, 14, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklósi, A.; Kubinyi, E.; Topál, J.; Gácsi, M.; Virányi, Z.; Csányi, V. A Simple Reason for a Big Difference: Wolves Do Not Look Back at Humans, but Dogs Do. Curr. Biol. 2003, 13, 763–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Albuquerque, N.; Guo, K.; Wilkinson, A.; Savalli, C.; Otta, E.; Mills, D. Dogs recognize dog and human emotions. Biol. Lett. 2016, 12, 20150883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Andics, A.; Miklósi, A. Neural processes of vocal social perception: Dog-human comparative fMRI studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 85, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I.; Forkman, B. Nonverbal Communication and Human–Dog Interaction. Anthrozoös 2014, 27, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prato-Previde, E.; Nicotra, V.; Fusar Poli, S.; Pelosi, A.; Valsecchi, P. Do dogs exhibit jealous behaviors when their owner attends to their companion dog? Anim. Cogn. 2018, 21, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prato-Previde, E.; Nicotra, V.; Pelosi, A.; Valsecchi, P. Pet dogs’ behavior when the owner and an unfamiliar person attend to a faux rival. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bert, F.; Gualano, M.R.; Camussi, E.; Pieve, G.; Voglino, G.; Siliquini, R. Animal assisted intervention: A systematic review of benefits and risks. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2016, 8, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Santaniello, A.; Dicé, F.; Carratú, R.C.; Amato, A.; Fioretti, A.; Menna, L.F. Methodological and Terminological Issues in Animal-Assisted Interventions: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews. Animals 2020, 10, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menna, L.F.; Santaniello, A.; Todisco, M.; Amato, A.; Borrelli, L.; Scandurra, C.; Fioretti, A. The Human–Animal Relationship as the Focus of Animal-Assisted Interventions: A One Health Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- International Association of Human Animal Interaction Organizations (IAHAIO) IAHAIO White Paper 2018, Updated for The IAHAIO Definitions for Animal Assisted Intervention and Guidelines for Wellness of Animals Involved in AAI. Available online: https://iahaio.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/iahaio-white-paper-2018-english.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2021).

- Kruger, K.A.; Serpell, J.A. Animal-assisted interventions in mental health: Definitions and Theoretical Foundations. In Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy; Fine, A.H., Ed.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menna, L.F. The scientific approach to Pet therapy. In The Method and Training According to the Federiciano Model, 1st ed.; University of Naples Federico II: Napoli, Italy, 2018; ISBN 979-12-200-3991-8. [Google Scholar]

- Glenk, L.M. Current Perspectives on Therapy Dog Welfare in Animal-Assisted Interventions. Animals 2017, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kręgiel, A.; Zaworski, K.; Kołodziej, E. Effects of animal-assisted therapy on parent-reported behaviour and motor activity of children with autism spectrum disorder. Health Probl. Civiliz. 2019, 13, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.R.; Ziviani, J.; Driscoll, C. “The connection just happens”: Therapists’ perspectives of canine-assisted occupational therapy for children on the autism spectrum. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2020, 67, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mims, D.; Waddell, R. Animal Assisted Therapy and Trauma Survivors. J. Evid.-Inf. Soc. Work 2016, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, E.; Ohlsen, S.; Thompson, J.; Hulin, J.; Knowles, L. The feasibility of brief dog-assisted therapy on university students stress levels: The PAwS study. J. Ment. Health 2017, 27, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Santaniello, A.; Garzillo, S.; Amato, A.; Sansone, M.; Di Palma, A.; Di Maggio, A.; Fioretti, A.; Menna, L.F. Animal-Assisted Therapy as a Non-Pharmacological Approach in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Retrospective Study. Animals 2020, 10, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, H.A.; Hayes, S.L.; Smith, J.P. Animal-Assisted Therapy in Pediatric Speech-Language with a Preschool Child with Severe Language Delay: A Single-Subject Design. Internet J. Allied Health Sci. Pract. 2019, 17, 1540–1580. [Google Scholar]

- Griscti, O.; Camilleri, L. The impact of dog therapy on nursing students’ heart rates and ability to pay attention in class. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 99, 101498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowska, I.; Ostrowska, B. Evaluation of the effectiveness of canine assisted therapy as a complementary method of rehabilitation in disabled children. Physiother. Q. 2018, 26, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolan-Nieroda, A.; Dudziak, J.; Drużbicki, M.; Pniak, B.; Guzik, A. Effect of Dog-Assisted Therapy on Psychomotor Development of Children with Intellectual Disability. Children 2020, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Álvarez, A.; Pardo-Vázquez, J.; De-Rosende-Celeiro, I.; Jácome-Feijoo, R.; Torres-Tobío, G. Assessing the Outcomes of an Animal-Assisted Intervention in a Paediatric Day Hospital: Perceptions of Children and Parents. Animals 2020, 10, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C.L.; Bibbo, J.; Rodriguez, K.E.; O’Haire, M.E. The effects of facility dogs on burnout, job-related well-being, and mental health in paediatric hospital professionals. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 1429–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beetz, A.; Schöfmann, I.; Girgensohn, R.; Braas, R.; Ernst, C. Positive Effects of a Short-Term Dog-Assisted Intervention for Soldiers With Post-traumatic Stress Disorder—A Pilot Study. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bergen-Cico, D.; Smith, Y.; Wolford, K.; Gooley, C.; Hannon, K.; Woodruff, R.; Spicer, M.; Gump, B. Dog Ownership and Training Reduces Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms and Increases Self-Compassion Among Veterans: Results of a Longitudinal Control Study. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2018, 24, 1166–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzla, J.; Altman, D.G. PRISMA Group: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta- analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- PubMed. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Science Direct Scopus. Available online: https://www.scopus.com (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Web of Science. Available online: https://clarivate.com/products/web-of-science/ (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Pet Partners. Available online: https://petpartners.org/learn/ (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Mueller, M.K.; Anderson, E.C.; King, E.K.; Urry, H.L. Null effects of therapy dog interaction on adolescent anxiety during a laboratory-based social evaluative stressor. Anxiety Stress. Coping 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, B.; Shenk, C.E.; Dreschel, N.E.; Wang, M.; Bucher, A.M.; Desir, M.P.; Chen, M.J.; Grabowski, S.R. Integrating Animal-Assisted Therapy Into TF-CBT for Abused Youth With PTSD: A Randomized Controlled Feasibility Trial. Child. Maltreat. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; Ziviani, J.; Driscoll, C.; Teoh, A.L.; Chua, J.M.; Cawdell-Smith, J. Canine Assisted Occupational Therapy for Children on the Autism Spectrum: A Pilot Randomised Control Trial. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 4106–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, A.; Heima, M.; Farkas, K.J. Therapy Dog Support in Pediatric Dentistry: A Social Welfare Intervention for Reducing Anticipatory Anxiety and Situational Fear in Children. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2020, 37, 615–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashden, J.; Lincoln, C.R.; Finn-Stevenson, M. Curriculum-Based Animal-Assisted Therapy in an Acute Outpatient Mental Health Setting. J. Contemp. Psychother. 2020, 51, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo-Claverol, M.; Malla-Clua, B.; Marquilles-Bonet, C.; Sol, J.; Jové-Naval, J.; Sole-Pujol, M.; Ortega-Bravo, M. Animal-Assisted Therapy Improves Communication and Mobility among Institutionalized People with Cognitive Impairment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgenson, C.; Clay, C.J.; Kahng, S. Evaluating preference for and reinforcing efficacy of a therapy dog to increase verbal statements. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2019, 53, 1419–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruskowski, K.A.; Gurney, J.M.; Cancio, L.C. Impact of the implementation of a therapy dog program on burn center patients and staff. Burns 2019, 46, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, C.X.; Tardif-Williams, C.Y. Turning the Page for Spot: The Potential of Therapy Dogs to Support Reading Motivation Among Young Children. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijker, C.; Van Der Steen, S.; Spek, A.; Leontjevas, R.; Enders-Slegers, M.-J. Social Development of Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder During Dog-Assisted Therapy: A Detailed Observational Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, R.; Vidal, L.; Ristol, F.; Domènec, E.; Segú, M.; Vico, C.; Gomez-Barros, N.; Ramos-Quiroga, J.A. Dog-Assisted Therapy for Children and Adolescents with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders a Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machová, K.; Procházková, R.; Eretová, P.; Svobodová, I.; Kotík, I. Effect of Animal-Assisted Therapy on Patients in the Department of Long-Term Care: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Costa, J.B.; Ichitani, T.; Juste, F.S.; Cunha, M.C.; De Andrade, C.R.F. Ensaio Clínico de Tratamento da Gagueira: Estudo piloto com variável monitorada, participação do cão na sessão de terapia. CoDAS 2019, 31, e20180274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffioen, R.E.; Van Der Steen, S.; Verheggen, T.; Enders-Slegers, M.; Cox, R. Changes in behavioural synchrony during dog-assisted therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder and children with Down syndrome. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2019, 33, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, M.L.; Funkquist, E.; Edner, A.; Engvall, G. Children report positive experiences of animal-assisted therapy in paediatric hospital care. Acta Paediatr. 2019, 109, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muela, A.; Azpiroz, J.; Calzada, N.; Soroa, G.; Aritzeta, A. Leaving A Mark, An Animal-Assisted Intervention Programme for Children Who Have Been Exposed to Gender-Based Violence: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thompkins, A.M.; Adkins, S.J.; Leopard, M.; Spencer, C.; Bentley, D.; Bolden, L.; Jagielski, C.H.; Richardson, E.; Goodman, A.M.; Schwebel, D.C. Dogs as an Adjunct to Therapy: Effects of Animal-Assisted Therapy on Rehabilitation Following Spinal Cord Injury. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosi, C.; Zaiontz, C.; Peragine, G.; Sarchi, S.; Bona, F. Randomized controlled study on the effectiveness of animal-assisted therapy on depression, anxiety, and illness perception in institutionalized elderly. Psychogeriatrics 2018, 19, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Sáez, E.; Pérez-Redondo, E.; González-Ingelmo, E. Effects of Dog-Assisted Therapy on Social Behaviors and Emotional Expressions: A Single-Case Experimental Design in 3 People with Dementia. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2019, 33, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.; Cuscaden, C.; Somers, J.F.; Simms, N.; Shaheed, S.; Kehoe, L.A.; Holowka, S.A.; Aziza, A.A.; Shroff, M.M.; Greer, M.-L.C. Easing anxiety in preparation for pediatric magnetic resonance imaging: A pilot study using animal-assisted therapy. Pediatr. Radiol. 2019, 49, 1000–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo-Claverol, M.; Casanova-Gonzalvo, C.; Malla-Clua, B.; Rodrigo-Claverol, E.; Jové-Naval, J.; Ortega-Bravo, M. Animal-Assisted Intervention Improves Pain Perception in Polymedicated Geriatric Patients with Chronic Joint Pain: A Clinical Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Protopopova, A.; Matter, A.L.; Harris, B.; Wiskow, K.M.; Donaldson, J.M. Comparison of contingent and noncontingent access to therapy dogs during academic tasks in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2019, 53, 811–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Fierro, N.; Vanegas-Farfano, M.; González-Ramírez, M.T.; Fierro, C.; Farfano, V.; Ramírez, G. Dog-Assisted Therapy and Dental Anxiety: A Pilot Study. Animals 2019, 9, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sánchez-Valdeón, L.; Fernández-Martínez, E.; Loma-Ramos, S.; López-Alonso, A.I.; Bayón-Darkistade, J.E.; Ladera, V. Canine-Assisted Therapy and Quality of Life in People with Alzheimer-Type Dementia: Pilot Study. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wijker, C.; Leontjevas, R.; Spek, A.; Enders-Slegers, M.-J. Effects of Dog Assisted Therapy for Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Exploratory Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 50, 2153–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grajfoner, D.; Harte, E.; Potter, L.M.; McGuigan, N. The Effect of Dog-Assisted Intervention on Student Well-Being, Mood, and Anxiety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dell, C.; Chalmers, D.; Stobbe, M.; Rohr, B.; Husband, A. Animal-assisted therapy in a Canadian psychiatric prison. Int. J. Prison. Health 2019, 15, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handlin, L.; Nilsson, A.; Lidfors, L.; Petersson, M.; Uvnäs-Moberg, K. The Effects of a Therapy Dog on the Blood Pressure and Heart Rate of Older Residents in a Nursing Home. Anthrozoös 2018, 31, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.B.; Osório, F.L. Impact of an animal-assisted therapy programme on physiological and psychosocial variables of paediatric oncology patients. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ward-Griffin, E.; Klaiber, P.; Collins, H.K.; Owens, R.L.; Coren, S.; Chen, F.S. Petting away pre-exam stress: The effect of therapy dog sessions on student well-being. Stress Health 2018, 34, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binfet, J.-T.; Passmore, H.-A.; Cebry, A.; Struik, K.; McKay, C. Reducing university students’ stress through a drop-in canine-therapy program. J. Ment. Health 2017, 27, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chubak, J.; Hawkes, R.; Dudzik, C.; Foose-Foster, J.M.; Eaton, L.; Johnson, R.H.; MacPherson, C.F. Pilot Study of Therapy Dog Visits for Inpatient Youth with Cancer. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 34, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuliani, F.; Jacquemettaz, M. Animal-assisted therapy used for anxiety disorders in patients with learning disabilities: An observational study. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2017, 14, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contalbrigo, L.; De Santis, M.; Toson, M.; Montanaro, M.; Farina, L.; Costa, A.; Nava, F.A. The Efficacy of Dog Assisted Therapy in Detained Drug Users: A Pilot Study in an Italian Attenuated Custody Institute. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fiocco, A.J.; Hunse, A.M. The Buffer Effect of Therapy Dog Exposure on Stress Reactivity in Undergraduate Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Calvo, P.; Fortuny, J.R.; Guzmán, S.; Macías, C.; Bowen, J.; García, M.L.; Orejas, O.; Molins, F.; Tvarijonaviciute, A.; Cerón, J.J.; et al. Animal Assisted Therapy (AAT) Program as a Useful Adjunct to Conventional Psychosocial Rehabilitation for Patients with Schizophrenia: Results of a Small-scale Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swall, A.; Ebbeskog, B.; Hagelin, C.L.; Fagerberg, I. ‘Bringing respite in the burden of illness’—dog handlers’ experience of visiting older persons with dementia together with a therapy dog. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 2223–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menna, L.F.; Santaniello, A.; Gerardi, F.; Di Maggio, A.; Milan, G. Evaluation of the efficacy of animal-assisted therapy based on the reality orientation therapy protocol in Alzheimer’s disease patients: A pilot study. Psychogeriatrics 2016, 16, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerepesi, A.; Dóka, A.; Miklosi, A. Dogs and their human companions: The effect of familiarity on dog–human interactions. Behav. Process. 2015, 110, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, E.; Bennett, P.; McGreevy, P. Current perspectives on attachment and bonding in the dog–human dyad. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2015, 8, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zilcha-Mano, S.; Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. An attachment perspective on human–pet relationships: Conceptualization and assessment of pet attachment orientations. J. Res. Pers. 2011, 45, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, J.; Beetz, A.; Schöberl, I.; Gee, N.; Kotrschal, K. Attachment security in companion dogs: Adaptation of Ainsworth’s strange situation and classification procedures to dogs and their human caregivers. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2018, 21, 389–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, R.; Bearman, G.; Brown, S.; Bryant, K.; Chinn, R.; Hewlett, A.; George, B.G.; Goldstein, E.J.; Holzmann-Pazgal, G.; Rupp, M.E.; et al. Animals in Healthcare Facilities: Recommendations to Minimize Potential Risks. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2015, 36, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hardin, P.; Brown, J.; Wright, M.E. Prevention of transmitted infections in a pet therapy program: An exemplar. Am. J. Infect. Control 2016, 44, 846–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, D.E.; Siebens, H.C.; Mueller, M.; Gibbs, D.M.; Freeman, L.M. Animal-assisted interventions: A national survey of health and safety policies in hospitals, eldercare facilities, and therapy animal organizations. Am. J. Infect. Control 2017, 45, 883–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elad, D. Immunocompromised patients and their pets: Still best friends? Vet. J. 2013, 197, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santaniello, A.; Varriale, L.; Dipineto, L.; Borrelli, L.; Pace, A.; Fioretti, A.; Menna, L. Presence of Campylobacterjejuni and C. coli in Dogs under Training for Animal-Assisted Therapies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santaniello, A.; Garzillo, S.; Amato, A.; Sansone, M.; Fioretti, A.; Menna, L.F. Occurrence of Pasteurella multocida in Dogs Being Trained for Animal-Assisted Therapy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santaniello, A.; Sansone, M.; Fioretti, A.; Menna, L.F. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Occurrence of ESKAPE Bacteria Group in Dogs, and the Related Zoonotic Risk in Animal-Assisted Therapy, and in Animal-Assisted Activity in the Health Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, A. Considering the “Dog” in Dog–Human Interaction. Front. Veter. Sci. 2021, 8, 2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, J.M.; Pauleen, C.; Bennett, P.C.; Grahame, J.C. A refinement and validation of the Monash Canine Personality Questionnaire (MCPQ). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 116, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratkin, J.L.; Sin, D.L.; Patali, E.A.; Gosling, S.D. Personality consistency in dogs: A metaanalysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kujala, M.V. Canine emotions as seen through human social cognition. Anim. Sentience 2017, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author, Year | General Information on Dogs | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Age (Years) | Sex | Breed | ||

| Mueller M., 2021 | 4 | 8–13 | m/f | n.a. | [39] |

| Allen B., 2021 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | Labrador | [40] |

| Hill J., 2020 | 1 | 3 | f | Labradoodle | [41] |

| Vincent A., 2020 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [42] |

| Kashden J., 2020 | 1 | 2 | f | poodle mix | [43] |

| Rodrigo-Claveron M., 2020 | 1 | 5 | m | German shepherd | [44] |

| Jorgenson C., 2020 | 1 | n.a. | n.a. | Labrador | [45] |

| Pruskowski K., 2020 | 6 | n.a. | n.a. | Golden, Poodle, Labrador, Shetland sheepdogs, Collie | [46] |

| Rousseau C. X., 2020 | 5 | adult | m/f | Bernese mountain dog, Maltese, Yorkshire terrier | [47] |

| Wijker C., 2020 | 4 | n.a. | n.a. | Labrador crossbreeds, Poodles | [48] |

| Vidal R., 2020 | 2 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [49] |

| Machova K., 2019 | 1 | 5 | f | Border Collie | [50] |

| Costa J., 2019 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | Golden | [51] |

| Griffioen R., 2019 | 2 | n.a. | m | Labrador, Labradoodle | [52] |

| Nilsson M., 2019 | 1 | 6 | f | Labradoodle | [53] |

| Muela A., 2019 | 4 | n.a. | n.a. | Labrador, Golden | [54] |

| Thompkins A., 2019 | n.a. | >18 months | m/f | Golden, Terrier mix, Havanese, Labrador | [55] |

| Ambrosi C., 2019 | 6 | n.a. | n.a. | golden, flat-coated | [56] |

| Perez-Saez E., 2019 | 1 | 3 | f | Labrador | [57] |

| Perez M., 2019 | 1 | 10 | f | Labrador | [58] |

| Rodrigo-Claverol M., 2019 | 3 | 4–3 | m/f | Golden, Cavalier King Charles | [59] |

| Protopopova A., 2019 | 3 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [60] |

| Cruiz- Fierro N., 2019 | 4 | average age of 40 months | m/f | English shepherd, Cchnauzer, Border Collie, Labrador | [61] |

| Sánchez-Valdeón L., 2019 | 1 | n.a. | n.a. | Labrador | [62] |

| Wijker C., 2019 | 13 | 2–10 | n.a. | Labradors, Labrador crossbreeds, Poodles, Golden, Golden crossbreeds, and a German Wirehaired Pointer. | [63] |

| Grajfoner, 2019 | 7 | n.a. | n.a. | Labrador, lhasa apso, Cocker Spaniels, Golden, Collie-Spaniel, Border Collie | [64] |

| Dell C., 2018 | 3 | 4, 6, 8 | m/f | Boxer and Bulldog | [65] |

| Handlin L., 2018 | 1 | 2 | f | Labradoodle | [66] |

| Silva N.B., 2018 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | Labrador, golden | [67] |

| Ward-Griffin E., 2017 | 7–12 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [68] |

| Binfet J., 2017 | 15–17 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [69] |

| Chubak J., 2017 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [70] |

| Giuliani F., 2017 | 1 | n.a. | n.a. | Border Collie | [71] |

| Contalbrigo L., 2017 | n.a. | adult | n.a. | n.a. | [72] |

| Fiocco A., 2017 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | Irish setter, Schnoodle, Miniature Poodles, Greyhound, King Charles Spaniel, Golden, and Australian Cattle Dog | [73] |

| Calvo P., 2016 | 5 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [74] |

| Swall A., 2016 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [75] |

| Menna L.F., 2016 | 1 | 7 | f | Labrador | [76] |

| First Author, Year | Research Goals | Activities with Dog | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mueller M., 2021 | reduce anxiety when experiencing a social stressor | social and physical interactions | [39] |

| Allen B., 2021 | improve the severity of PTSD symptoms | n.a. | [40] |

| Hill J., 2020 | achievement of occupational goals among autistic children | 7 sessions for 1 h occupational activities | [41] |

| Vincent A., 2020 | reducing anxiety and situational fear among children | 1 h of free interactions | [42] |

| Kashden J., 2020 | improve mood in an outpatient setting | 20 weeks of sessions lasting 50 min Mutt-i-grees curriculum, which is based on the concepts of human–dog interactions | [43] |

| Rodrigo-Claveron M., 2020 | improve communication and mobility of people with cognitive impairments | 2 session per week for 6 months, physical interactions | [44] |

| Jorgenson C., 2020 | increase verbal statements through various contingencies | 3–7 sessions per day, 1–2 days a week (30 min/1 h) Playing with the dog | [45] |

| Pruskowski K., 2020 | improving duration and quality of rehabilitation sessions and physical therapy | rehabilitation activities: walking with the dog; caregiving activities: brushing, petting | [46] |

| Rousseau C.X., 2019 | supporting reading motivation among young children | 45 min per session, children read in the company of the dog | [47] |

| Wijker C., 2020 | improving the social development of adults with autism spectrum disorder | 60 min session, interaction activities | [48] |

| Vidal R., 2019 | improvements in social skills, a reduction in internalized and externalized symptomatology | weekly sessions of 45 min over 3 months, interaction activities. | [49] |

| Machova K., 2019 | positively activate hospitalized patients | 12 weeks of sessions lasting 20 min walks, playing ball, obedience exercises | [50] |

| Costa J., 2019 | stuttering treatment | 12 weeks of sessions lasting 50 min. Passive participation: the dog was wearing a vest containing pictures, words, and phrases. Active participation: selected an object. Participants were allowed to interact with the dog voluntarily during all sessions. Free interactions | [51] |

| Griffioen R., 2019 | help children with autism-spectrum disorder and Down syndrome (behavioral synchrony) | 6 weekly sessions of 30 min psychomotor and socialization activities, obstacle course | [52] |

| Nilsson M., 2019 | complementary treatment in pediatric hospital care | a calm period and an active period with tricks guided by the handler | [53] |

| Muela A., 2019 | reduce the internalizing and externalizing symptoms associated with traumatic stress disorder in children exposed to domestic violence | 14 weeks of sessions lasting 1 h playing, carrying out tasks such as grooming and feeding, etc. | [54] |

| Thompkins A., 2019 | improve affect, reduce stress, and reduce affect for red pain in individuals undergoing occupational therapy during rehabilitation from traumatic SCIs | physical interactions | [55] |

| Ambrosi C., 2019 | effectiveness on depression and anxiety among institutionalized elderly individuals | 10 sessions per week for 30 min of verbal and nonverbal social interactions, stroking the dog, giving or throwing food or a toy | [56] |

| Perez-Saez E., 2019 | improving social behaviors and emotional expression among people with dementia | free interactions | [57] |

| Perez M., 2019 | reducing anxiety in pediatric patients preparing for MRI | 20–60 min of the interaction included sitting near the dog, petting the dog, and engaging in low-level play | [58] |

| Rodrigo-Claverol M., 2019 | improving pain perception in polymedicated geriatric patients with chronic joint pain | 12 weekly sessions of 60 min of physical interactions | [59] |

| Protopopova A., 2019 | improving academic tasks in children with autism spectrum disorder | 30 min session, once per day, 2–3 days per week, free interactions | [60] |

| Cruiz-Fierro N., 2019 | help control anxiety during dental procedures | touching or stroking the dog during periods of stress | [61] |

| Sánchez-Valdeón L., 2019 | improving the quality of life of people with Alzheimer’s disease | weekly session (1 h) for 12 months, physical interactions | [62] |

| Wijker C., 2019 | reducing stress and improving social awareness and communication among adults with ASD | 2 h per day (non-consecutive), maximum of 2 days per week | [63] |

| Griffioen R.E., 2019 | improve students’ mood, well-being, and anxiety | 1 session for 20 min handler and dog interactions or dog-only interactions | [64] |

| Dell C., 2018 | improve welfare of prisoners | 24 sessions over 8 months 30 min experiential learning with the dog, basic obedience (e.g., sit, heel) | [65] |

| Handlin L., 2018 | improve systolic blood pressure/rate and heart disease among the elderly | physical activity (stroking, playing, etc.) | [66] |

| Silva N.B., 2018 | improve physiological and psychosocial variables of pediatric oncology patients | 30 min session per week caregiving activities, socialization, sensorial and upper limb stimulation | [67] |

| Ward-Griffin E., 2017 | reducing pre-exam stress among students | 90 min session, free interactions with the dogs | [68] |

| Binfet J., 2017 | reduce stress among college students | drop-in program once a week, variable time, spending time with the dog | [69] |

| Chubak J., 2017 | potential benefits for young people hospitalized with cancer | 20 min of stroking the dog, the dog showing a trick to the patient | [70] |

| Giuliani F., 2017 | benefits for individuals with difficulties learning | 30 min playing ball, petting, and brushing the dog | [71] |

| Contalbrigo L., 2017 | helping in the rehabilitation of drug-addicted prisoners | once a week for 6 months (60 min): cooperative games, problem solving games, agility dog path, role playing, obedience exercises, contact and care activities, olfactory discrimination games, exercises of communication with the body, free interactions | [72] |

| Fiocco A., 2017 | buffering effect of stress responses among college students | 10 min free interactions | [73] |

| Calvo P., 2016 | rehabilitation for patients with schizophrenia | 6 months of biweekly 1 h sessions, emotional bonding, dog walking, and dog training with play | [74] |

| Swall A., 2016 | promote human welfare and stimulate training of physical, social, and cognitive functions. | the activities for the patient included close contact with the dog by touching its fur, cuddling, and talking, searching for hidden sweets, throwing balls, or other activities | [75] |

| Menna L.F., 2016 | the therapeutic approach was based on the stimulation of cognitive functions such as attention, language skills, and spatial–temporal orientation. | intervention occurred once a week for 45 min over a 6-month period. Activities with the dog were based on the formal ROT protocol | [76] |

| First Author, Year | Choice of Dog | Dog Training | Health Status | Dog Ownership | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methods of Choosing | Temperament | Behavioral Veterinary Medical Examination | Health Protocols | ||||

| Mueller M., 2021 | Pet Partners Program | n.a. | Pet Partners Program | n.a. | yes | n.a. | [39] |

| Allen B., 2021 | retired service dogs | n.a. | local service dog organization | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [40] |

| Hill J., 2020 | examination temperament and behavior | n.a. | obedience | yes | yes | handled | [41] |

| Vincent A., 2020 | n.a. | n.a. | Therapy Dogs International or Pet Partners | n.a. | n.a. | handled | [42] |

| Kashden J., 2020 | independently licensed therapy dog training facility | n.a. | 12 weeks, standard therapy dog training | n.a. | n.a. | handled | [43] |

| Rodrigo-Claveron M., 2020 | Liackhoff test | n.a. | clicker training | yes | yes | n.a. | [44] |

| Jorgenson C., 2020 | n.a. | Assistance Dogs International | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | handled | [45] |

| Pryskowski K., 2020 | n.a. | n.a. | American Kennel Club canine good citizen. Therapy organization: Therapy Animals of San Antonio, Pet Partners, and Alliance of Therapy Dogs | n.a. | yes | handled | [46] |

| Rousseau C. X., 2020 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | handled | [47] |

| Wijker C., 2020 | n.a. | n.a. | Dutch Service dog Foundation | n.a. | n.a. | handled | [48] |

| Vidal R., 2020 | n.a. | trained and tested to work with people | CTAC Method (Center of dog assisted Therapy) | yes | n.a. | n.a. | [49] |

| Machova K., 2019 | AAT certification | interest in working with people, no aggressivity | obedience, to cope with stressful situations | n.a. | n.a. | handled | [50] |

| Costa J., 2019 | tested for desirable reactions in responses to unknown people; unpredictable visual and sound stimuli; aggressive human voice; threatening gestures; places with a large concentration of people; | n.a. | Instituto Cão Terapeuta and Amor Canino Terapia organizations | n.a. | yes | handled | [51] |

| Griffioen R., 2019 | n.a. | mild-mannered | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | handled | [52] |

| Nilsson M., 2019 | certificated for use with children in health care | n.a. | trained for use with children in health care | n.a. | yes | handled | [53] |

| Muela A., 2019 | n.a. | n.a. | positive reinforcement techniques | n.a. | yes | n.a. | [54] |

| Thompkins A., 2019 | n.a. | n.a. | Hand in Paw | n.a. | n.a. | owned | [55] |

| Ambrosi C., 2019 | certification aptitude tests for therapy dogs | n.a. | professionally trained | n.a. | n.a. | handled | [56] |

| Perez-Saez E., 2019 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [57] |

| Perez M., 2019 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | yes | handled | [58] |

| Rodrigo-Claverol M., 2019 | n.a. | suitable character | Ilerkan Association | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [59] |

| Protopopova A., 2019 | n.a. | n.a. | American Kennel Club Canine Good Citizen evaluation. All dogs are certified through and registered with a national therapy dog registry (e.g., Pet Partners, Alliance of Therapy Dogs) | n.a. | n.a. | handled | [60] |

| Cruiz- Fierro N., 2019 | certification Council for Professional Dog Trainers (CCPDT) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | yes | handled | [61] |

| Sánchez-Valdeón L., 2019 | n.a. | socialized, had a stable, friendly nature | trained for this purpose by a canine specialist | n.a. | yes | n.a. | [62] |

| Wijker C., 2019 | n.a. | trained and tested to work with people | Dutch service dog foundation (guidelines to protect and monitor animal welfare) | yes | yes | n.a. | [63] |

| Grajfoner, 2019 | n.a. | n.a. | therapet, Canine Concern Scotland Trust (Scottish Charity No) | n.a. | n.a. | handled | [64] |

| Dell C., 2018 | screening, orientation, evaluation, and placement | mild-mannered, energetic, or laid-back | St. John’s Ambulance Therapy Dog program | n.a. | n.a. | handled | [65] |

| Handlin L., 2018 | n.a. | n.a. | 1 year, “Vårdhundskolan” (Sweden) | n.a. | n.a. | handled | [66] |

| Silva N.B., 2018 | n.a. | n.a. | docility, obedience training, and socialization | yes | yes | handled | [67] |

| Ward-Griffin E., 2017 | n.a. | no history of aggression or biting, good obedience, and friendly interactions with strangers | Vancouver ecoVillage Therapy Dog Programme | n.a. | yes | handled | [68] |

| Binfet J., 2017 | BARK program | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | yes | handled | [69] |

| Chubak J., 2017 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | yes | owned | [70] |

| Giuliani F., 2017 | n.a. | n.a. | Swiss Romande Cynology Federation | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [71] |

| Contalbrigo L., 2017 | simulation test | n.a. | specifically trained to perform do-assisted interventions with various kinds of patients; well-socialized | yes | yes | handled | [72] |

| Fiocco A., 2017 | St. John’s Ambulance Therapy Dog program | docile manner | trained to interact with people in a docile manner | n.a. | yes | n.a. | [73] |

| Calvo P., 2016 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | yes | n.a. | n.a. | [74] |

| Swall A., 2016 | n.a. | n.a. | the dog is trained to know how to approach the person in a soft, gentle way (Swedish Standard Institute) | n.a. | n.a. | handled | [75] |

| Menna L.F., 2016 | according to Federico II Model of Healthcare Zooanthropology | n.a. | educational program for pet therapy at the La Voce del Cane Dog Educational Centre, which follows the guidelines of the Italian National Educational Sports Center | yes | yes | owned | [76] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santaniello, A.; Garzillo, S.; Cristiano, S.; Fioretti, A.; Menna, L.F. The Research of Standardized Protocols for Dog Involvement in Animal-Assisted Therapy: A Systematic Review. Animals 2021, 11, 2576. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11092576

Santaniello A, Garzillo S, Cristiano S, Fioretti A, Menna LF. The Research of Standardized Protocols for Dog Involvement in Animal-Assisted Therapy: A Systematic Review. Animals. 2021; 11(9):2576. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11092576

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantaniello, Antonio, Susanne Garzillo, Serena Cristiano, Alessandro Fioretti, and Lucia Francesca Menna. 2021. "The Research of Standardized Protocols for Dog Involvement in Animal-Assisted Therapy: A Systematic Review" Animals 11, no. 9: 2576. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11092576

APA StyleSantaniello, A., Garzillo, S., Cristiano, S., Fioretti, A., & Menna, L. F. (2021). The Research of Standardized Protocols for Dog Involvement in Animal-Assisted Therapy: A Systematic Review. Animals, 11(9), 2576. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11092576