Integrating Livestock Grazing and Sympatric Takin to Evaluate the Habitat Suitability of Giant Panda in the Wanglang Nature Reserve

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

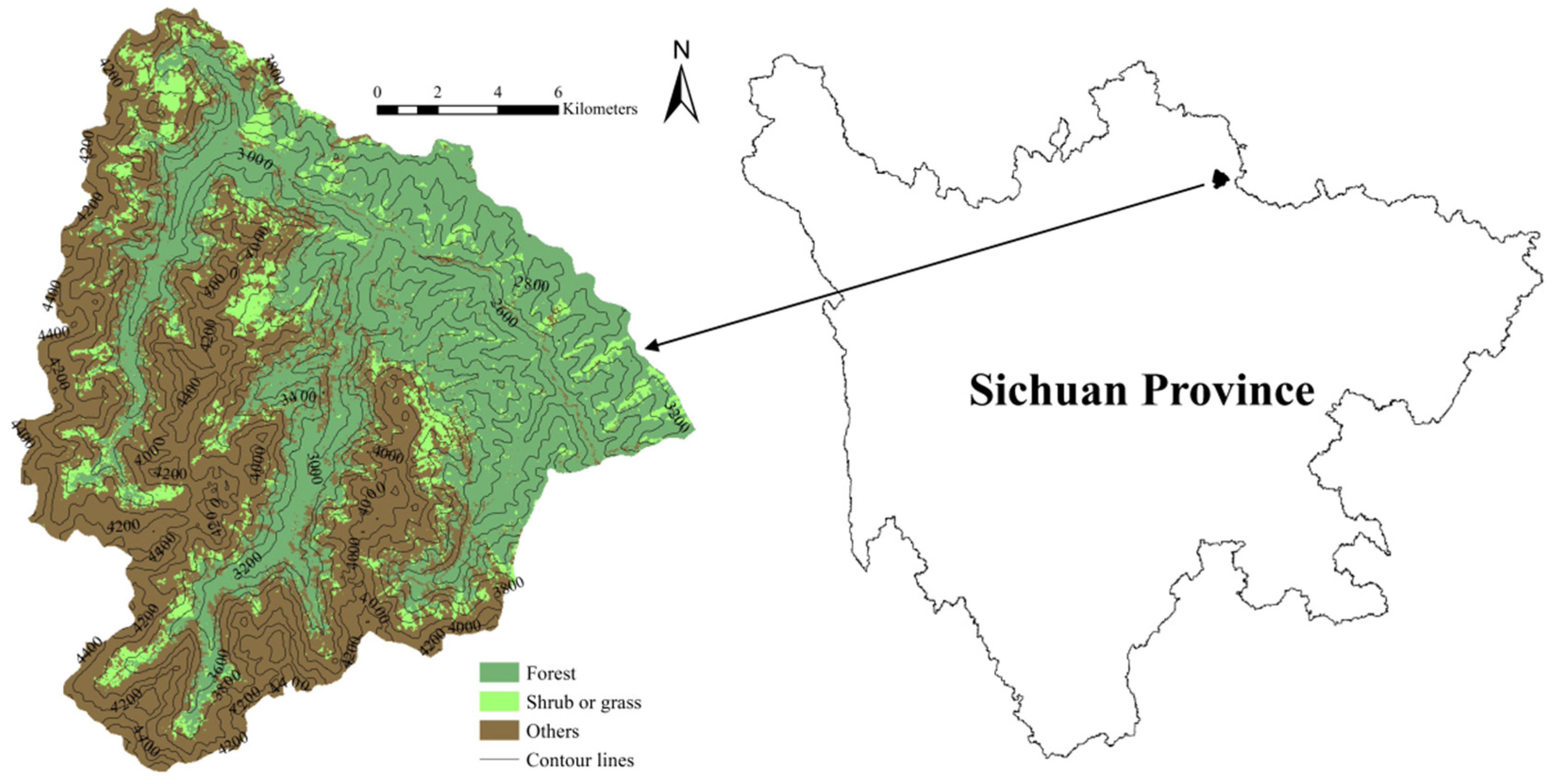

2.1. Study Area

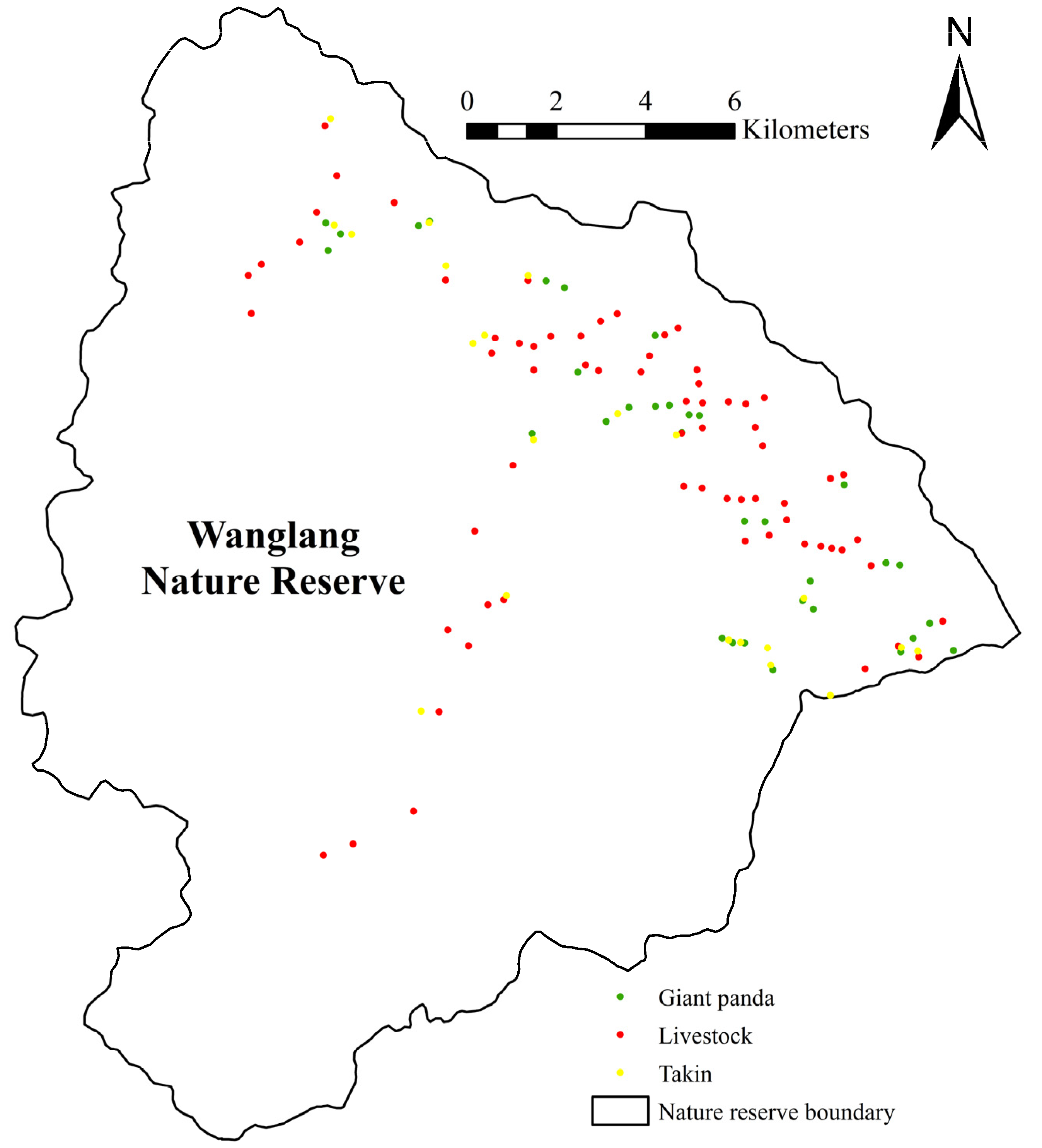

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Habitat Suitability Assessment of Giant Panda

2.4. Habitat Overlap between Livestock and Giant Panda

2.5. Habitat Overlap between Takin and Giant Panda

3. Results

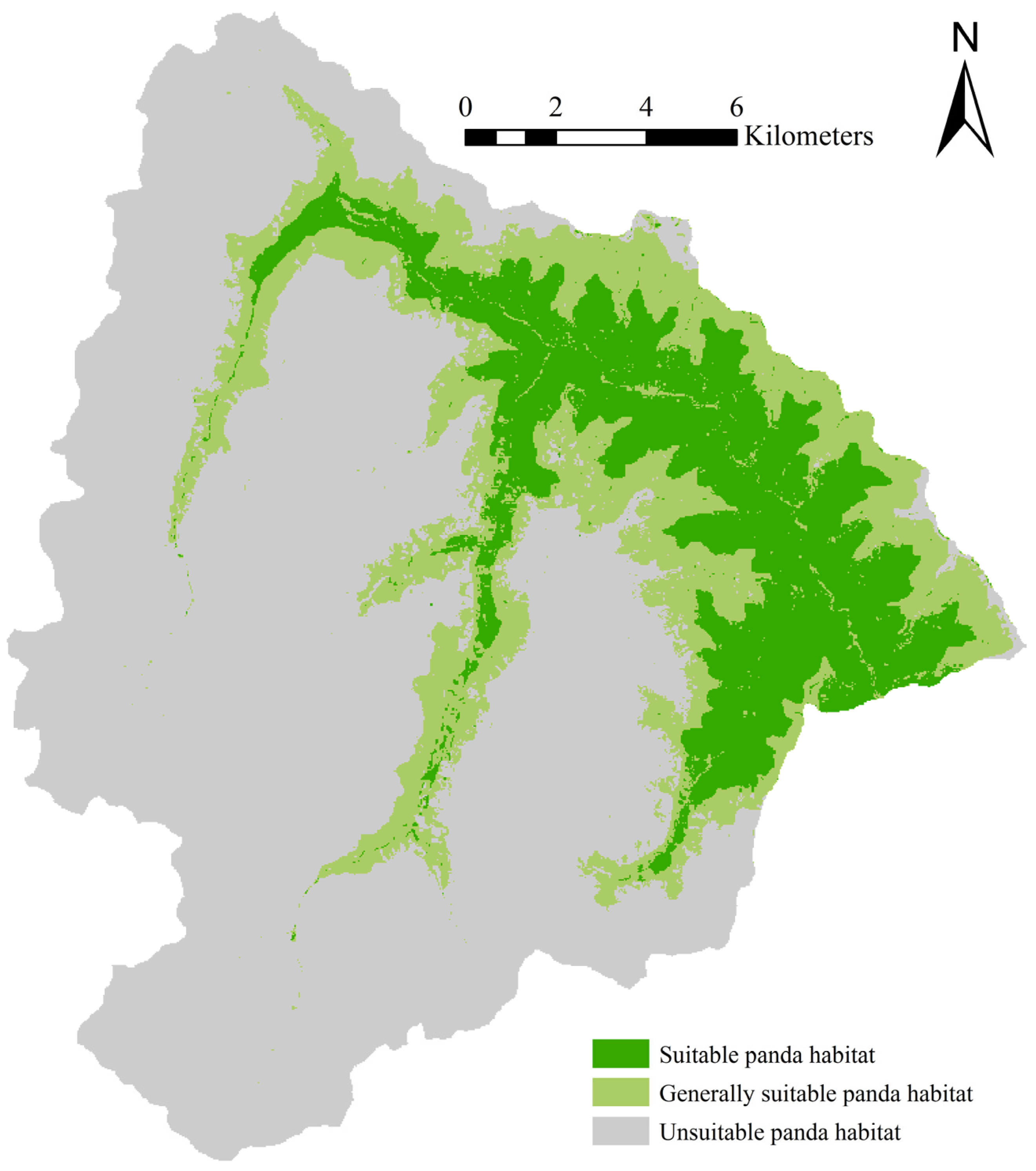

3.1. Habitat Suitability Characteristics of Giant Panda

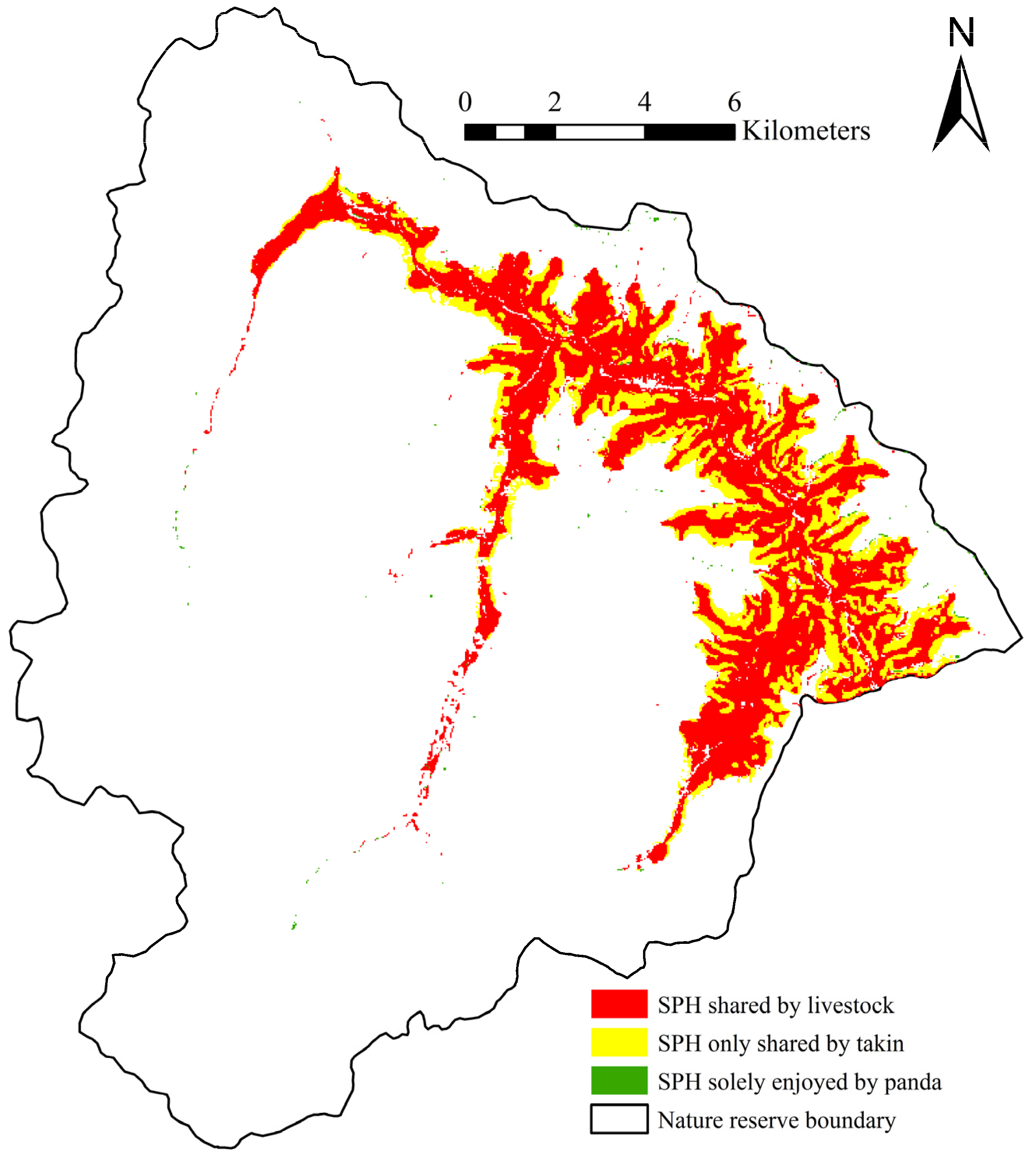

3.2. Suitable Giant Panda Habitat Shared by Livestock

3.3. Suitable Giant Panda Habitat Shared by Takin

4. Discussion

4.1. Habitat Status of Giant Pandas under Natural Conditions

4.2. Livestock Grazing Threatens Habitat Quality and Habitat Selection of Giant Panda

4.3. Potential Effects of Takin on the Habitat Selection of Giant Pandas

4.4. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wei, F.; Nie, Y.; Miao, H.; Lu, H.; Hu, H. Advancements of the researches on biodiversity loss mechanisms. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2014, 59, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sichuan Forestry Department. The Pandas of Sichuan: The 4th Survey Report on Giant Panda in Sichuan Province; Sichuan Publishing House of Science and Technology: Chengdu, China, 2015; pp. 10, 130.

- Kang, D. A review of the impacts of four identified major human disturbances on the habitat and habitat use of wild giant pandas from 2015 to 2020. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 763, 142975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Zhao, L.; Song, G. Competition relationship between giant panda and livestock in Wanglang National Nature Reserve, Sichuan. J. Northeast For. Univ. 2011, 39, 74–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Hull, V.; Zhang, J.; Huang, J.; Liu, D.; Huang, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, H. Comparative space use patterns of wild giant pandas and livestock. Acta Theriol. Sin. 2016, 36, 138–151. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, J.; Hull, V.; Huang, J.; Liu, D.; Zhou, J.; Sun, M.; Zhang, H. Comparative activity patterns of wild giant pandas and livestock. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.V.; Pimm, S.L.; Li, S.; Zhao, L.; Luo, C. Free-ranging livestock threaten the long-term survival of giant pandas. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 216, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. Giant Pandas: Natural Heritage of the Humanity; China Forestry Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2006; pp. 30–39, 82. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Wu, P. Large-scale and Middle-scale Coexistent Mammals of Giant Panda in Xiaoxiangling Mountains. Sichuan J. Zool. 2007, 26, 88–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, D.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Chen, Y. Can conservation of single surrogate species protect co-occurring species? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 6290–6296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration. The 4th National Survey Report on Giant Panda in China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2021; p. 139. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Yuan, S.; Zhou, Z.; Nie, Y.; Zhang, Z. Microhabitat separation between giant panda and golden takin in the Qinling Mountains and implications for conservation. North-West. J. Zool. 2017, 13, 109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Kang, D.; Li, J.; Huang, J.; Song, Z. Comparison of habitat use of giant panda, takin and Sichuan golden monkey. J. Northeast For. Univ. 2017, 45, 81–83. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.; Liu, X.; Shao, X.; Zhu, Y.; Cai, Q. GIS application in evaluating the potential habitat of giant pandas in Guanyinshan nature reserve, Shaanxi Province. J. Environ. Inform. 2013, 21, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Linderman, M.; Ouyang, Z.; An, L.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H. Ecological degradation in protected areas the case of Wolong nature reserve for giant pandas. Science 2001, 292, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, X.; Skidmore, A.K.; Bronsveld, M.C. Assessment of giant panda habitat based on integration of expert system and neural network. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2006, 17, 438–443. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Ouyang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Liu, J. Assessment of giant panda habitat in the Daxiangling Mountain Range, Sichuan, China. Biodivers. Sci. 2006, 13, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Liu, J.; Xiao, H.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, H. An assessment of giant panda habitat in Wolong Nature Reserve. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2001, 21, 1869–1874. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Hull, V.; Ouyang, Z.; Li, R.; Connor, T.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Silet, B.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J. Divergent responses of sympatric species to livestock encroachment at fine spatiotemporal scales. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 209, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, K.; Dai, Q.; Gu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Qi, D.; Gu, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, W.; Yang, B.; et al. Effects of roads on giant panda distribution: A mountain range scale evaluation. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, M.; Chen, L.; Luo, G.; Gu, X.; Wang, G.; Ran, J. Suitable habitat prediction and overlap analysis of two sympatric species, giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) and Asiatic black bear (Ursus thibetanus) in Liangshan Mountains. Biodivers. Sci. 2018, 26, 1180–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ran, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, H.; Sun, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, S. Habitat selection by giant pandas and grazing livestock in the Xiaoxiangling Mountains of Sichuan Province. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2003, 23, 2253–2259. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, C.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Yu, L.; Yuan, D.; Li, Y. Preliminary surveys of wild animals using infrared camera in Wanglang National Nature Reserve, Sichuan Province. Biodivers. Sci. 2018, 26, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, H.; Guan, T.; Zhu, D.; Li, W.; Zhou, F.; Zhao, D.; Li, C.; Zhang, S.L. Assessment of effective conservation of the Sichuan takin by giant panda reserves through functional zoning. Integr. Zool. 2020, 15, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, S.; Zhao, L.; Huang, J. The trend of human interference activities and management countermeasures in Wanglang Nature Reserve, Sichuan. Sichuan J. Zool. 2003, 22, 251–254. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X.; Fu, Q.; Wang, L.; Yang, B.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y. Habitat suitability assessment and overlap analysis of Rusa unicolor and Budorcas taxicolor in Anzihe Reserve, Sichuan Province. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 4842–4851. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, L.; Kang, D.; Wang, X.; Yang, H.; Li, J. Comparative habitat use by giant pandas in primary and secondary forests in Wanglang Nature Reserve. J. Biol. 2014, 31, 49–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, D. Research on the Habitat Selection of Giant Pandas. Ph.D. Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J. SDMtoolbox: A python-based GIS toolkit for landscape genetic, biogeographic and species distribution model analyses. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2014, 5, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.; Anderson, R.; Schapire, R. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Model. 2006, 190, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, R.; Yang, H.; Luo, W.; Wang, M.; Lu, X.; Huang, T.; Zhao, J.; Li, Q. Predicting the potential distribution of the Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri (Kuwayama), in China using the MaxEnt model. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Luo, C.; Xu, W.; Zhou, Z.; Ouyang, Z.; Zhang, L. Habitat prediction for forest musk deer (Moschus berezovskii) in Qinling mountain range based on niche model. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2011, 31, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Schaller, G.B. Wolong’s Giant Panda; Sichuan Science and Technology Press: Chengdu, China, 1985; p. 93. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, W.; Lv, Z.; Zhu, X.; Wang, D.; Wang, H.; Long, Y.; Fu, D.; Zhou, X. Chance for Lasting Survival; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2001; p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Xu, W.; Ouyang, Z.; Liu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, L.; Huang, J. The application of Ecological-Niche factor analysis in giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) habitat assessment. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2008, 28, 821–828. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Ouyang, Z.; Xu, W.; Long, Q.; Xie, Q. Assessment of the Potential Suitable Habitat and the Actual Use Habitat of Giant Pandas in Wolong. J. Sichuan Agric. Univ. 2017, 35, 116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Toxopeus, A.G.; Skidmore, A.K.; Shao, X.; Dang, G.; Wang, T.; Prins, H.H.T. Giant panda habitat selection in Foping Nature Reserve, China. J. Wildlife Manag. 2005, 69, 1623–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, V.; Roloff, G.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Zhou, S.; Huang, J.; Xu, W.; Ouyang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J. A synthesis of giant panda habitat selection. Ursus 2014, 25, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Forestry Administration. The 3rd National Survey Report on Giant Panda in China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2006; pp. 139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Swaisgood, R.R.; Dai, Q.; Yang, Z.; Yuan, S.; Owen, M.A.; Pilfold, N.W.; Yang, X.; Gu, X.; Hong, Z.; et al. Giant panda distributional and habitat-use shifts in a changing landscape. Conserv. Lett. 2018, 11, e12575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, J.; Hull, V.; Huang, J.; Liu, D.; Xie, H.; Zou, X.; Zhang, H. Comparison of the bamboo-grazing behavior of giant pandas and livestock. Chin. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. 2021, 27, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, V.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, S.; Huang, J.; Viña, A.; Liu, W.; Tuanmu, M.; Li, R.; Liu, D.; Xu, W.; et al. Impact of livestock on giant pandas and their habitat. J. Nat. Conserv. 2014, 22, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Dayananda, B.; Fu, X.; Yuan, D.; Tu, Z.; Luo, C.; Li, J. Temporal niche patterns of large mammals in Wanglang National Nature Reserve, China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e01015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Zhong, W.; Song, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, L.; Gong, H. Present status of studies on eco-biology of takin. Acta Theriol. Sin. 2003, 23, 161–167. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, T.; Ge, B.; Chen, L.; You, Z.; Tang, Z.; Liu, H.; Song, Y. Home range and fidelity of Sichuan takin. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2015, 35, 1862–1868. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Han, H.; Zhou, H.; Cao, S.; Zhang, Z. Microhabitat use and separation between giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca), takin (Budorcas taxicolor), and goral (Naemorhedus griseus) in Tangjiahe Nature Reserve, China. Folia Zool. 2018, 67, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Dayananda, B.; Jeffree, R.A.; Tian, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, B.; Zheng, Y.; Jing, Y.; Si, P.; Li, J.Q. Giant panda distribution and habitat preference: The influence of sympatric large mammals. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 24, e01221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J. Research on the Giant Pandas; Shanghai Scientific and Technological Education Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2001; p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Deng, D.; Yan, W. Effect of giant panda ecotourism on giant pandas and their habitats and strategies. J. Sichuan Forestry Sci. Technol. 2011, 32, 102–105. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hull, V. Mixed-method study on medicinal herb collection in relation to wildlife conservation: The case of giant pandas in China. Integr. Zool. 2019, 14, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Kang, D. Integrating Livestock Grazing and Sympatric Takin to Evaluate the Habitat Suitability of Giant Panda in the Wanglang Nature Reserve. Animals 2021, 11, 2469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082469

Chen X, Wang X, Li J, Kang D. Integrating Livestock Grazing and Sympatric Takin to Evaluate the Habitat Suitability of Giant Panda in the Wanglang Nature Reserve. Animals. 2021; 11(8):2469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082469

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xiaoyu, Xiaorong Wang, Junqing Li, and Dongwei Kang. 2021. "Integrating Livestock Grazing and Sympatric Takin to Evaluate the Habitat Suitability of Giant Panda in the Wanglang Nature Reserve" Animals 11, no. 8: 2469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082469

APA StyleChen, X., Wang, X., Li, J., & Kang, D. (2021). Integrating Livestock Grazing and Sympatric Takin to Evaluate the Habitat Suitability of Giant Panda in the Wanglang Nature Reserve. Animals, 11(8), 2469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082469