Cognitive Enrichment in Practice: A Survey of Factors Affecting Its Implementation in Zoos Globally

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Approval

2.2. Survey

2.3. Respondents

2.4. Data Handling and Statistics

2.4.1. Data Cleaning

2.4.2. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Summary

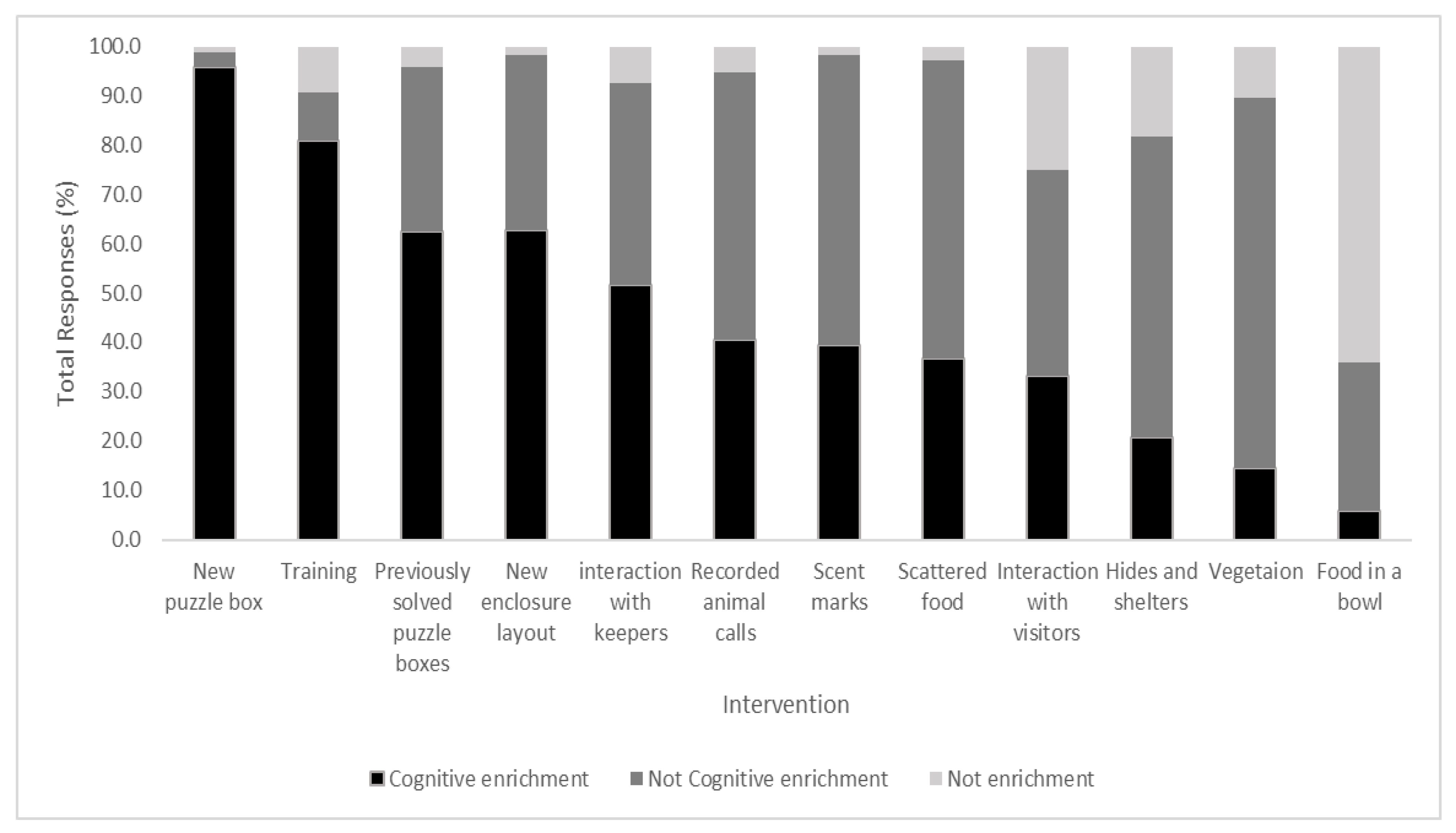

3.2. What Is Cognitive Enrichment?

3.3. Importance of Cognitive Enrichment

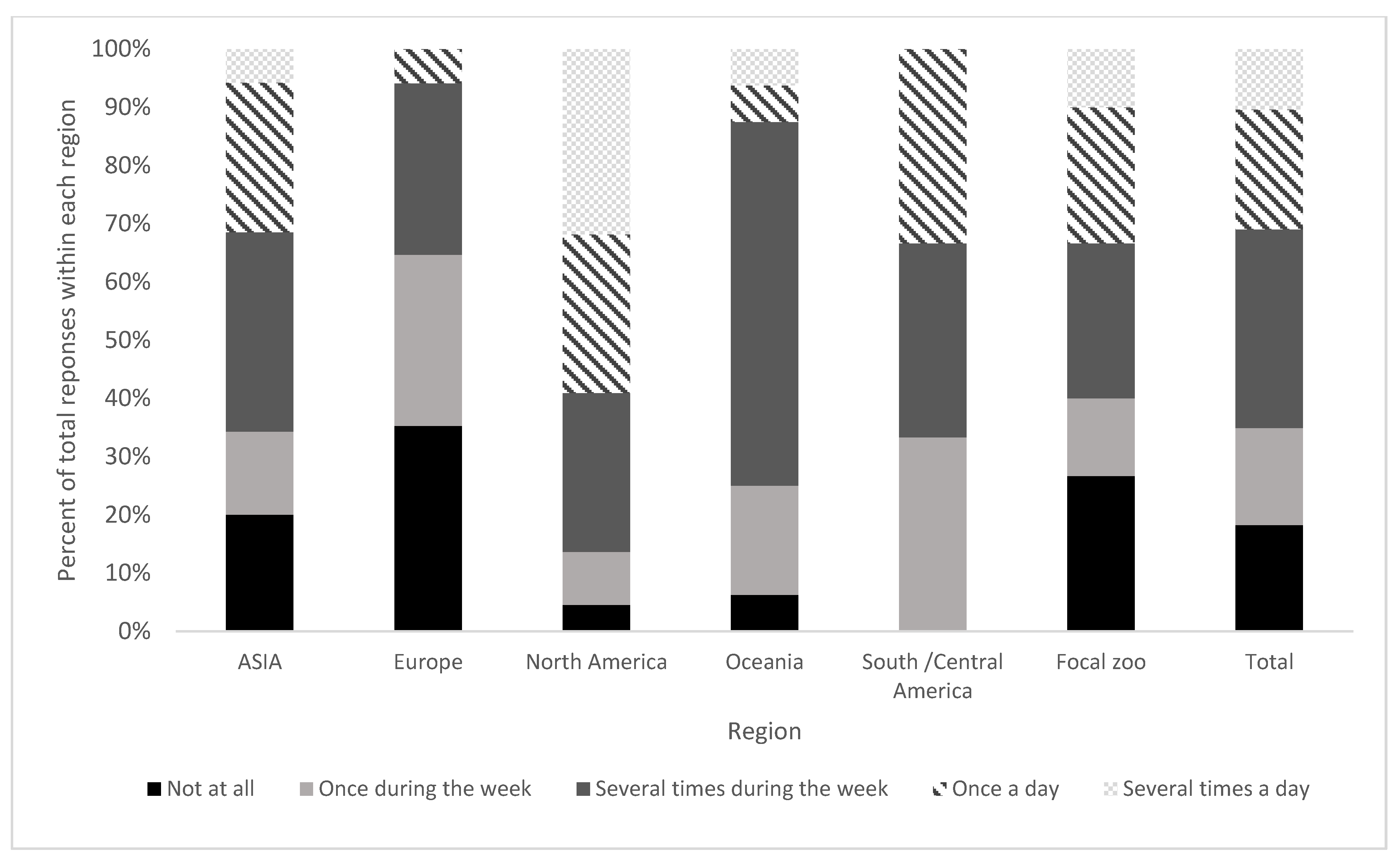

3.4. Creation and Delivery of Enrichment

3.5. Use of Cognitive Enrichment

3.6. Factors Affecting the Use of Cognitive Enrichment

3.7. Factors Affecting the Success of Cognitive Enrichment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mellor, D.; Beausoleil, N. Extending the ‘Five Domains’ model for animal welfare assessment to incorporate positive welfare states. Anim. Welf. 2015, 24, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoo and Aquarium Association (ZAA). 8.1 Policy—Animal Welfare. 2019, pp. 1–3. Available online: https://www.zooaquarium.org.au/common/Uploaded%20files/Policies/P_Animal%20Welfare.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Dawkins, M.S. Behavioural deprivation: A central problem in animal welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1988, 20, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, E.F.; Cram, D.L.; Quinn, J.L. Individual variation in spontaneous problem-solving performance among wild great tits. Anim. Behav. 2011, 81, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, E.A.; Hugart, J.A.; Kirkpatrick-Steger, K. Pigeons show same-different conceptualization after training with complex visual stimuli. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Processes 1995, 21, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrew, W.C. Chimpanzee technology. Science 2010, 328, 579–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inglis, I.R.; Forkman, B.; Lazarus, J. Free food or earned food? A review and fuzzy model of contrafreeloading. Anim. Behav. 1997, 53, 1171–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Horik, J.; Emery, N.J. Evolution of cognition. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 2011, 2, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Waal, F.B.; Ferrari, P.F. Towards a bottom-up perspective on animal and human cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2010, 14, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Špinka, M.; Wemelsfelder, F. Environmental challenge and animal agency. In Animal Welfare, 2nd ed.; Appleby, M.C., Mench, J.A., Olsson, I.A.S., Hughes, B.O., Eds.; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2011; pp. 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Meehan, C.L.; Mench, J.A. The challenge of challenge: Can problem solving opportunities enhance animal welfare? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 102, 246–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newberry, R.C. Environmental enrichment: Increasing the biological relevance of captive environments. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1995, 44, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.J. Environmental enrichment an historical perspective. In Environmental Enrichment for Captive Animals, 1st ed.; Young, R.J., Kirkwood, J.K., Hubrecht, R.C., Roberts, E.A., Eds.; UFAW Animal Welfare Series; Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK, 2003; Volume 1, pp. 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Arranz, L.; De Castro, N.M.; Baeza, I.; Maté, I.; Viveros, M.P.; De la Fuente, M. Environmental enrichment improves age-related immune system impairment: Long-term exposure since adulthood increases life span in mice. Rejuvenation Res. 2010, 13, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.C.D.; Palme, R.; Moreira, N. How environmental enrichment affects behavioral and glucocorticoid responses in captive blue-and-yellow macaws (Ara ararauna). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 201, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skibiel, A.; Trevino, H.; Naugher, K. Comparison of several types of enrichment for captive felids. Zoo Biol. 2007, 26, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shyne, A. Meta-analytic review of the effects of enrichment on stereotypic behavior in zoo mammals. Zoo Biol. 2006, 25, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grippo, A.J.; Ihm, E.; Wardwell, J.; McNeal, N.; Scotti, M.-A.L.; Moenk, D.A.; Chandler, D.L.; LaRocca, M.A.; Preihs, K. The effects of environmental enrichment on depressive-and anxiety-relevant behaviors in socially isolated prairie voles. Psychosom. Med. 2014, 76, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meagher, R.; Mason, G. Environmental enrichment reduces signs of boredom in caged mink. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Azevedo, C.S.; Cipreste, C.F.; Young, R.J. Environmental enrichment: A GAP analysis. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 102, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, F. Cognitive enrichment and welfare: Current approaches and future directions. Anim. Behav. Cogn. 2017, 4, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, F. Great ape cognition and captive care: Can cognitive challenges enhance well-being? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 135, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesterwind, S.; Nürnberg, G.; Puppe, B. Impact of structural and cognitive enrichment on the learning performance, behavior and physiology of dwarf goats (Capra aegagrus hircus). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 177, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumeij, J.T.; Hommers, C.J. Foraging ‘enrichment’as treatment for pterotillomania. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 111, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, F.; Davies, S.; Madigan, A.; Warner, A.; Kuczaj, S. Cognitive enrichment for bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus): Evaluation of a novel underwater maze device. Zoo Biol. 2013, 32, 608–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celli, M.L.; Tomonaga, M.; Udono, T.; Teramoto, M. Tool use task as environmental enrichment for captive chimpanzees. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2003, 81, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, M.; Powell, B.J. Behavioural flexibility and problem-solving in a tropical lizard. Biol. Lett. 2011, 8, 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, V.A. Cognitive ability in fish. Fish Physiol. 2006, 24, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hoy, J.; Murray, P.; Tribe, A. Thirty years later: Enrichment practices for captive mammals. Zoo Biol. 2010, 29, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.; Sherwen, S.; Clark, F. Advances in Applied Zoo Animal Welfare Science. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2018, 21, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, F.; Gray, S.; Bennett, P.; Mason, L. High-tech and tactile: Cognitive enrichment for zoo-housed gorillas. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.; Sherwen, S.; Webber, S. An evaluation of interactive projections as digital enrichment for orangutans. Zoo Biol. 2021, 40, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, F. Marine mammal cognition and captive care: A proposal for cognitive enrichment in zoos and aquariums. J. Zoo Aquar Res. 2013, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherdson, D.J. Tracing the path of environmental enrichment in zoos. In Second Nature: Environmental Enrichment for Captive Animals; Shepherdson, D.J., Mellen, J.D., Hitchins, M., Eds.; Smithsonian Washington: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, G. Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 2010, 15, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, P.E.; Brereton, J.E.; Rowden, L.J. What’s new from the zoo? An analysis of ten years of zoo-themed research output. Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, T.C.; Krochmal, A.R.; LaDage, L.D. Reptilian cognition: A more complex picture via integration of neurological mechanisms, behavioral constraints, and evolutionary context. Bioessays 2019, 41, 1900033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellen, J.; Sevenich MacPhee, M. Philosophy of environmental enrichment: Past, present, and future. Zoo Biol. 2001, 20, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, J. Do data characteristics change according to the number of scale points used? An experiment using 5-point, 7-point and 10-point scales. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 50, 61–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, S.J.; Lehman, D.R.; Peng, K.; Greenholtz, J. What’s wrong with cross-cultural comparisons of subjective Likert scales?: The reference-group effect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jegatheesan, B. Influence of cultural and religious factors on attitudes toward animals. In Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, J.-C. Species comparative studies and cognitive development. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005, 9, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker-Drob, E.M.; Briley, D.A.; Harden, K.P. Genetic and environmental influences on cognition across development and context. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 22, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, I.A.S.; Dahlborn, K. Improving housing conditions for laboratory mice: A review of ‘environmental enrichment’. Lab. Anim. 2002, 36, 243–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Braithwaite, V.A. Effects of predation pressure on the cognitive ability of the poeciliid Brachyraphis episcopi. Behav. Ecol. 2005, 16, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewall, K.B. Social complexity as a driver of communication and cognition. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2015, 55, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alligood, C.; Leighty, K. Putting the “E” in SPIDER: Evolving trends in the evaluation of environmental enrichment efficacy in zoological settings. Anim. Behav. Cogn. 2015, 2, 200–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors Combined | Do Not Work Directly with Animals | Work Directly with Animals |

|---|---|---|

| Limited training | Limited training opportunities for keepers to develop their enrichment skills | My limited knowledge about building enrichment |

| Limited knowledge | Limited keeper knowledge of enrichment principles | My personal knowledge of types of enrichment |

| Importance of enrichment to management/workplace | Limited management prioritization of enrichment | How important enrichment is to the company I work for |

| Time observe animal response | Restricted opportunity to observe animal response | My time to observe animal use of enrichment |

| Limited funds | Limited funds available for enrichment | My limited access to funds to build or buy enrichment |

| Time constraints | Time constraints | The extent to which I have more pressing duties to complete |

| Past enrichment failures | Past enrichment failures | My personal experience with past enrichment failures |

| Restrictions/regulation on enrichment | Management restrictions on certain types of enrichment | The zoo regulations of enrichment practices I must follow |

| Concerns around unnatural enrichment | Restrictions on “unnatural” enrichment | Concerns that the public will respond negatively to unnatural enrichment |

| Number of animals | Keeper to animal ratio | The number of different animals I need to provide enrichment for |

| Workload for others | Workload for colleagues or other keepers | The effect the enrichment will have on other keepers’ workload |

| Asia | Europe | North America | Oceania | South/Central America | Focal Zoo | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 53 (29.9) | 23 (13) | 24 (13.6) | 19 (10.7) | 6 (3.4) | 52 (29.4) | 177 (100) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 26 (14.7) | 16 (9) | 20 (11.3) | 13 (7.3) | 4 (2.3) | 36 (20.3) | 115 (65) |

| Male | 24 (13.6) | 6 (3.4) | 4 (2.3) | 6 (3.4) | 2 (1.1) | 14 (7.9) | 56 (31.6) |

| Not provided | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.1) | 5 (2.8) |

| Other | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) |

| Age | |||||||

| 18–24 | 11 (6.2) | 3 (1.7) | 3 (1.7) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.7) | 22 (12.4) |

| 25–34 | 23 (13) | 10 (5.6) | 11 (6.2) | 8 (4.5) | 3 (1.7) | 15 (8.5) | 70 (39.5) |

| 35–44 | 16 (9) | 7 (4) | 7 (4) | 3 (1.7) | 2 (1.1) | 16 (9) | 51 (28.8) |

| 45–54 | 3 (1.7) | 3 (1.7) | 3 (1.7) | 5 (2.8) | 1 (0.6) | 9 (5.1) | 24 (13.6) |

| 55–64 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 6 (3.4) | 7 (4) |

| 65–74 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) |

| Not provided | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) |

| Current role | |||||||

| Animal worker | 32 (18.1) | 16 (9) | 15 (8.5) | 13 (7.3) | 4 (2.3) | 28 (15.8) | 108 (61) |

| Management | 4 (2.3) | 5 (2.8) | 7 (4) | 6 (3.4) | 2 (1.1) | 10 (5.6) | 34 (19.2) |

| Non Animal worker | 17 (9.6) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 14 (7.9) | 35 (19.8) |

| Experience in current role | |||||||

| 1–5 years | 32 (18.1) | 13 (7.3) | 13 (7.3) | 7 (4) | 6 (3.4) | 26 (14.7) | 97 (54.8) |

| 6–10 years | 9 (5.1) | 2 (1.1) | 6 (3.4) | 6 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 9 (5.1) | 32 (18.1) |

| 11–15 years | 4 (2.3) | 4 (2.3) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.7) | 13 (7.3) |

| 16–20 years | 3 (1.7) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 5 (2.8) | 13 (7.3) |

| 20+ years | 3 (1.7) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 4 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 9 (5.1) | 20 (11.3) |

| Not provided | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.1) |

| Highest level of education | |||||||

| Less than high school | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) |

| High school graduate | 3 (1.7) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 9 (5.1) |

| Technical collage/Trade qualification | 5 (2.8) | 7 (4) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 15 (8.5) | 30 (16.9) |

| Undergraduate degree | 31 (17.5) | 5 (2.8) | 19 (10.7) | 10 (5.6) | 2 (1.1) | 27 (15.3) | 94 (53.1) |

| Masters degree | 12 (6.8) | 5 (2.8) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (1.7) | 3 (1.7) | 9 (5.1) | 34 (19.2) |

| Doctorate | 2 (1.1) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 9 (5.1) |

| Relevant education | |||||||

| No relevant education | 19 (10.7) | 14 (7.9) | 13 (7.3) | 11 (6.2) | 4 (2.3) | 21 (11.9) | 82 (46.3) |

| Technical collage/Trade qualification | 7 (4) | 9 (5.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 17 (9.6) | 36 (20.3) |

| Undergraduate degree | 19 (10.7) | 0 (0) | 11 (6.2) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.6) | 13 (7.3) | 47 (26.6) |

| Masters degree | 7 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 11 (6.2) |

| Doctorate | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) |

| Enrichment Type | Asia | Europe | North America | Oceania | South/Central America | Focal Zoo | Global * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Enrichment | 7 (0.13) | 7 (0.12) | 7 (0.04) | 7 (0.1) | 7 (0.33) | 7 (0.08) | 7 (0.05) |

| Feeding Enrichment | 7 (0.18) | 7 (0.06) | 7 (0.19) | 7 (0.12) | 7 (0) | 7 (0.12) | 7 (0.07) |

| Structural Enrichment | 7 (0.11) | 7 (0.16) | 7 (0.14) | 7 (0.19) | 7 (0) | 7 (0.17) | 7 (0.07) |

| Social Enrichment | 7 (0.18) | 7 (0.11) | 7 (0.23) | 7 (0.22) | 7 (0) | 7 (0.1) | 7 (0.08) |

| Tactile Enrichment | 6 (0.17) | 6 (0.25) | 6 (0.25) | 7 (0.26) | 6 (0.54) | 7 (0.17) | 7 (0.09) |

| Olfactory Enrichment | 6 (0.19) | 7 (0.2) | 6.5 (0.22) | 7 (0.3) | 7 (0.49) | 7 (0.14) | 7 (0.09) |

| Visual Enrichment | 6 (0.17) | 6 (0.28) | 6 (0.28) | 7 (0.24) | 5.5 (0.76) | 7 (0.18) | 6 (0.1) |

| Auditory Enrichment | 6 (0.21) | 4 (0.4) | 5.5 (0.37) | 6 (0.38) | 5.5 (0.67) | 6 (0.2) | 6 (0.12) |

| Human-Animal Interaction | 5 (0.24) | 4 (0.29) | 7 (0.34) | 5 (0.39) | 6.5 (0.71) | 5 (0.21) | 5 (0.12) |

| Animal Group | Global Total * | ASIA | Europe | North America | Oceania | South/Central America | Focal Zoo | Not Receiving CE but Should * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carnivores | 135 (76.3) | 37 (69.8) | 18 (78.3) | 20 (83.3) | 11 (57.9) | 5 (83.3) | 44 (84.6) | 60 (33.9) |

| Primates (exclusive of great apes) | 126 (71.2) | 33 (62.3) | 20 (87) | 21 (87.5) | 8 (42.1) | 4 (66.7) | 40 (76.9) | 54 (30.5) |

| Parrots | 105 (59.3) | 23 (43.4) | 11 (47.8) | 18 (75) | 15 (78.9) | 5 (83.3) | 33 (63.5) | 68 (38.4) |

| Great apes | 98 (55.4) | 26 (49.1) | 13 (56.5) | 11 (45.8) | 5 (26.3) | 2 (33.3) | 41 (78.8) | 55 (31.1) |

| Small Carnivores | 94 (53.1) | 19 (35.8) | 11 (47.8) | 20 (83.3) | 6 (31.6) | 4 (66.7) | 34 (65.4) | 57 (32.2) |

| Other birds | 87 (49.2) | 19 (35.8) | 9 (39.1) | 14 (58.3) | 11 (57.9) | 4 (66.7) | 30 (57.7) | 71 (40.1) |

| Elephants | 79 (44.6) | 27 (50.9) | 9 (39.1) | 5 (20.8) | 3 (15.8) | 3 (50) | 32 (61.5) | 52 (29.4) |

| Ungulates | 75 (42.4) | 15 (28.3) | 9 (39.1) | 16 (66.7) | 6 (31.6) | 4 (66.7) | 25 (48.1) | 62 (35.0) |

| Reptiles | 72 (40.7) | 11 (20.8) | 4 (17.4) | 14 (58.3) | 11 (57.9) | 3 (50) | 29 (55.8) | 79 (44.6) |

| Marsupials and monotremes | 71 (40.1) | 11 (20.8) | 4 (17.4) | 10 (41.7) | 13 (68.4) | 1 (16.7) | 32 (61.5) | 55 (31.1) |

| Marine Mammals | 62 (35) | 12 (22.6) | 8 (34.8) | 5 (20.8) | 6 (31.6) | 2 (33.3) | 29 (55.8) | 56 (31.6) |

| Corvids | 47 (26.6) | 6 (11.3) | 5 (21.7) | 14 (58.3) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (33.3) | 18 (34.6) | 55 (31.1) |

| Fish | 30 (16.9) | 4 (7.5) | 4 (17.4) | 4 (16.7) | 5 (26.3) | 1 (16.7) | 12 (23.1) | 67 (37.9) |

| Amphibians | 30 (16.9) | 5 (9.4) | 3 (13) | 6 (25) | 3 (15.8) | 0 (0) | 13 (25) | 63 (35.6) |

| I do not know | 18 (10.2) | 5 (9.4) | 1 (4.3) | 2 (8.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (19.2) | (0.0) |

| Factor | Asia | Europe | North America | Oceania | South/Central America | Focal Zoo | Work Directly with Animals | Management | Do Not Work Directly with Animals | Gobal Average * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time constraints | 5.3 (0.20) | 5.9 (0.33) | 5.5 (0.33) | 4.9 (0.38) | 6.3 (0.42) | 5.4 (0.23) | 5.4 (0.15) | 5.6 (0.26) | 5.2 (0.25) | 5.4 (0.12) |

| Time observe animal response | 5.4 (0.19) | 4.7 (0.45) | 4.8 (0.31) | 4.9 (0.36) | 6.5 (0.50) | 5.1 (0.22) | 5.2 (0.16) | 5.1 (0.29) | 5.1 (0.26) | 5.1 (0.12) |

| Limited funds | 5.2 (0.25) | 4.7 (0.46) | 4.4 (0.45) | 4.7 (0.45) | 3.8 (0.79) | 5.4 (0.23) | 5 (0.19) 12 | 4.2 (0.33) 1 | 5.7 (0.26) 2 | 5.0 (0.14) |

| Number of animals | 5.5 (0.23) BC | 5.1 (0.44) ABC | 4.8 (0.37) ABC | 4.0 (0.50) AB | 6.7 (0.21) C | 4.2 (0.26) A | 4.9 (0.2) | 4.6 (0.31) | 4.7 (0.3) | 4.8 (0.15) |

| Workload for others | 5.5 (0.20) A | 4.6 (0.40) AB | 3.6 (0.41) B | 3.4 (0.45) B | 4.7 (1.12) AB | 4.5 (0.27) AB | 4.4 (0.19) | 4.5 (0.36) | 5.1 (0.29) | 4.6 (0.15) |

| Importance of enrichment to management/ workplace | 5.3 (0.24) A | 3.2 (0.47) B | 3.1 (0.44) B | 3.8 (0.47) AB | 4.8 (0.95) AB | 3.4 (0.27) B | 4.3 (0.21) 1 | 2.9 (0.32) 2 | 4.5 (0.34) 12 | 4.0 (0.16) |

| Restrictions regulation on enrichment | 4.7 (0.25) A | 2.4 (0.33) B | 3.4 (0.45) AB | 2.9 (0.38) B | 3.8 (0.95) AB | 4.8 (0.23) A | 4.2 (0.19) 1 | 3.1 (0.31) 2 | 4.5 (0.31) 12 | 4.0 (0.15) |

| Limited knowledge | 4.9 (0.25) A | 3.7 (0.28) AB | 2.8 (0.32) B | 3.0 (0.29) B | 4.8 (0.79) AB | 3.4 (0.25) B | 3.8 (0.18) | 3.8 (0.3) | 3.9 (0.32) | 3.8 (0.14) |

| Limited training | 4.6 (0.29) A | 3.3 (0.38) AB | 2.7 (0.35) B | 2.4 (0.29) B | 4.2 (0.65) AB | 3.4 (0.28) B | 3.5 (0.19) | 3.3 (0.36) | 3.9 (0.35) | 3.6 (0.15) |

| Concerns around unnatural enrichment | 4.4 (0.28) A | 2.3 (0.35) B | 2.7 (0.38) B | 2.7 (0.39) B | 3.7 (1.15) AB | 3.8 (0.27) AB | 3.2 (0.21) | 3.7 (0.32) | 4.3 (0.27) | 3.5 (0.16) |

| Past enrichment failures | 4.2 (0.28) A | 3.0 (0.37) AB | 2.5 (0.35) B | 2.5 (0.42) AB | 4.2 (1.01) AB | 3.2 (0.23) AB | 3.1 (0.2) 1 | 3.1 (0.27) 12 | 4.3 (0.29) 2 | 3.3 (0.15) |

| Factor | Asia | Europe | North America | Oceania | South/Central America | Focal Zoo | Global Average * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keeper interest | 6.1 (0.14) | 5.7 (0.36) | 5.5 (0.36) | 5.3 (0.39) | 6.7 (0.33) | 5.8 (0.21) | 5.8 (0.11) |

| Time constraints | 5.2 (0.23) | 6.1 (0.22) | 6.1 (0.25) | 5.3 (0.37) | 6.2 (0.48) | 5.7 (0.24) | 5.6 (0.12) |

| Enrichment design | 4.7 (0.24) A | 5.5 (0.33) AB | 5.6 (0.27) AB | 5.8 (0.34) AB | 6.7 (0.33) AB | 6.3 (0.15) B | 5.6 (0.12) |

| Level of difficulty for keepers | 5.3 (0.17) A | 5.2 (0.35) AB | 4.9 (0.34) AB | 4.2 (0.33) B | 4.8 (0.70) AB | 5.6 (0.22) A | 5.2 (0.12) |

| Animal personality | 5.3 (0.23) | 4.8 (0.39) | 5.0 (0.39) | 5.4 (0.28) | 5.0 (0.63) | 4.8 (0.26) | 5.0 (0.13) |

| Animal intelligence | 5.3 (0.25) A | 4.5 (0.47) AB | 4.4 (0.39) AB | 5.3 (0.32) A | 4.2 (0.87) AB | 3.8 (0.28) B | 4.6 (0.15) |

| Visitor interest | 4.3 (0.23) A | 2.4 (0.34) B | 2.5 (0.31) B | 2.8 (0.36) B | 1.5 (0.50) B | 2.3 (0.21) B | 3.0 (0.14) |

| Animal sex | 3.5 (0.22) A | 1.9 (0.34) B | 1.5 (0.20) B | 2.0 (0.29) B | 1.7 (0.49) AB | 1.8 (0.17) B | 2.3 (0.12) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hall, B.A.; McGill, D.M.; Sherwen, S.L.; Doyle, R.E. Cognitive Enrichment in Practice: A Survey of Factors Affecting Its Implementation in Zoos Globally. Animals 2021, 11, 1721. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11061721

Hall BA, McGill DM, Sherwen SL, Doyle RE. Cognitive Enrichment in Practice: A Survey of Factors Affecting Its Implementation in Zoos Globally. Animals. 2021; 11(6):1721. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11061721

Chicago/Turabian StyleHall, Belinda A., David M. McGill, Sally L. Sherwen, and Rebecca E. Doyle. 2021. "Cognitive Enrichment in Practice: A Survey of Factors Affecting Its Implementation in Zoos Globally" Animals 11, no. 6: 1721. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11061721

APA StyleHall, B. A., McGill, D. M., Sherwen, S. L., & Doyle, R. E. (2021). Cognitive Enrichment in Practice: A Survey of Factors Affecting Its Implementation in Zoos Globally. Animals, 11(6), 1721. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11061721