Socialization in Commercial Breeding Kennels: The Use of Novel Stimuli to Measure Social and Non-Social Fear in Dogs

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Subjects

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Analysis

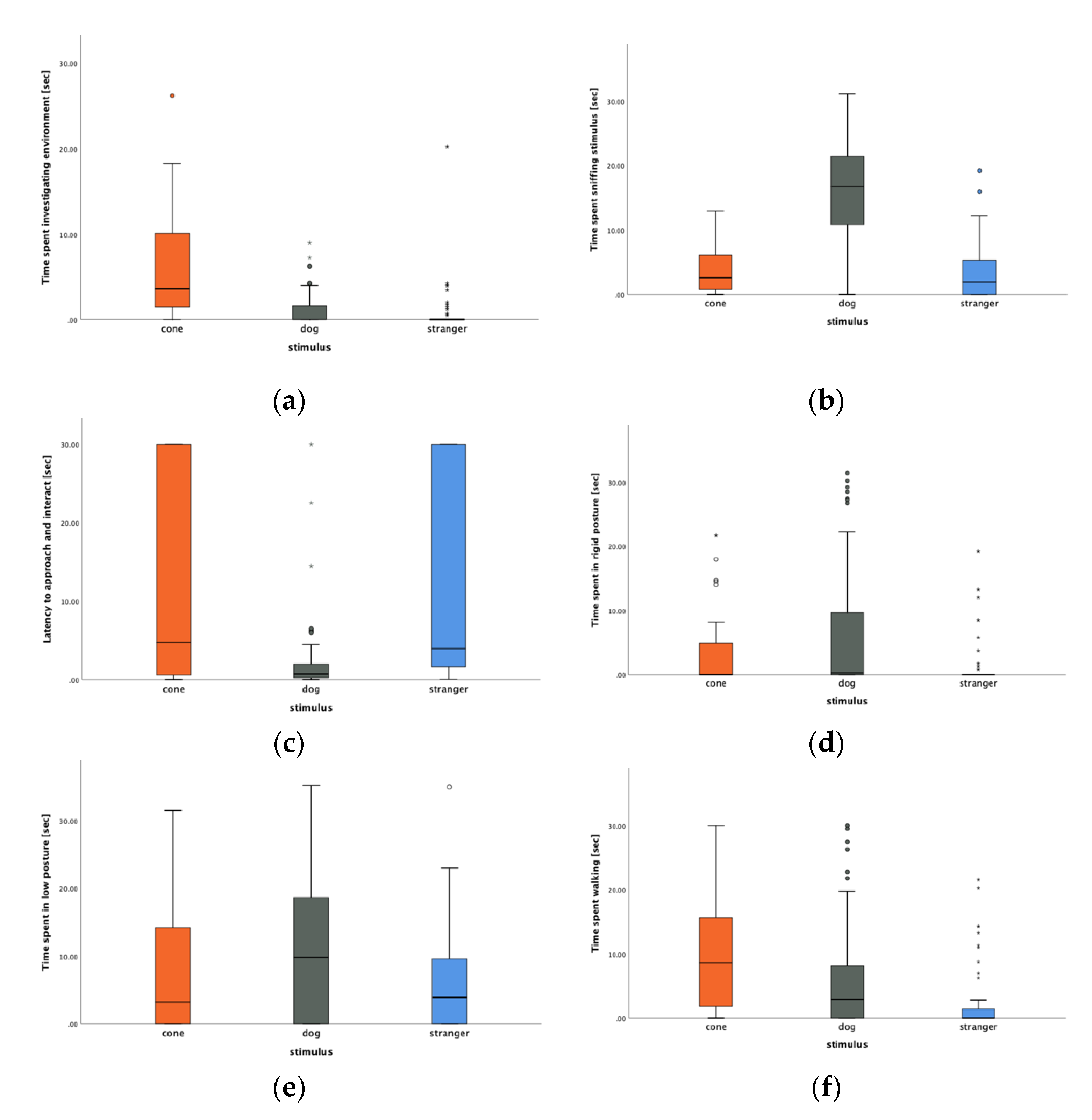

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mugenda, L.; Shreyer, T.; Croney, C. Refining canine welfare assessment in kennels: Evaluating the reliability of Field Instantaneous Dog Observation (FIDO) scoring. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, S.; Pedernera, C.; Candeloro, L.; Ferri, N.; Velarde, A.; Dalla Villa, P. Development of a new welfare assessment protocol for practical application in long- term dog shelters. Vet. Record 2016, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubrecht, R.C.; Serpell, J.A.; Poole, T.B. Correlates of pen size and housing conditions on the behaviour of kenneled dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1992, 34, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, N.J.; Gaines, S.A.; Bradshaw, J.W.S. Behavioural and glucocorticoid responses of dogs (Canis familiaris) to kennelling: Investigating mitigation of stress by prior habituation. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerda, B.; Schilder, M.B.H.; van Hooff, J.A.R.A.M.; de Vries, H.W. Manifestations of Chronic and Acute Stress in Dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1997, 52, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreschel, N.A. The effects of fear and anxiety on health and lifespan in pet dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2010, 125, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scullion Hall, L.E.; Robinson, S.; Finch, J.; Buchanan-Smith, H.M. The influence of facility and home pen design on the welfare of the laboratory-housed dog. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2017, 83, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waiblinger, S.; Boivin, X.; Pedersen, V.; Tosi, M.-V.; Janczak, A.M.; Visser, E.K.; Jones, R.B. Assessing the human–animal relationship in farmed species: A critical review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2006, 101, 185–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, F.D.; Duffy, D.L.; Serpell, J.A. Mental health of dogs formerly used as ‘breeding stock’ in commercial breeding establishments. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 135, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.E.; Jordan, M.; Colon, M.; Shreyer, T.; Croney, C.C. Evaluating FIDO: Developing and pilot testing the Field Instantaneous Dog Observation tool. Pet Behav. Sci. 2017, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, J.; Shreyer, T.; Ha, J.; Croney, C. Improving canine welfare in commercial breeding (CB) operations: Evaluating rehoming candidates. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019, 220, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, J.; Bauer, A.; Croney, C. A cross-sectional study to estimate prevalence of periodontal disease in a population of dogs (Canis familiaris) in commercial breeding facilities in Indiana and Illinois. PLoS ONE 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stella, J.; Hurt, M.; Bauer, A.; Gomes, P.; Ruple, A.; Beck, A.; Croney, C. Does flooring substrate impact kennel and dog cleanliness in commercial breeding facilities? Animals 2018, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerda, B.; Schilder, M.B.H.; van Hooff, J.A.R.A.M.; de Vries, H.W.; Mol, J.A. Behavioural, saliva cortisol and heart rate responses to different types of stimuli in dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1998, 58, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellato, A.C.; Flint, H.E.; Widowski, T.M.; Serpell, J.A.; Niel, L. Assessment of fear-related behaviors displayed by companion dogs (Canis familiaris) in response to social and non-social stimuli. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 188, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA APHIS Animal Welfare Act Regulation 9 CFR, Part 3. Available online: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2013-title9-vol1/xml/CFR-2013-title9-vol1-chapI-sub-chapA.xml (accessed on 17 March 2020).

- Flint, H.E.; Coe, J.B.; Serpell, J.A.; Pearl, D.L.; Niel, L. Identification of Fear Behaviors Shown by Puppies in Response to Nonsocial Stimuli. J. Vet. Behav. 2018, 28, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.K.; Mae, Y.L. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhne, F.; Hößler, J.C.; Struwe, R. Effects of human–dog familiarity on dogs’ behavioural responses to petting. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 142, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, S.; Kennedy, D.; Watson, R.; Valsecchi, P.; Arnott, G. Revisiting a previously validated temperament test in shelter dogs, including an examination of the use of fake model dogs to assess conspecific sociability. Animals 2019, 9, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, K.A.; Stein, J.; Taylor, R.C. Robots in the service of animal behavior. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2012, 5, 466–472. [Google Scholar]

- Frohnwieser, A.; Murray, J.C.; Pike, T.W.; Wilkinson, A. Using robots to understand animal cognition. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 2016, 105, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patricelli, G.L.; Krakauer, A.H. Tactical Allocation of Effort among Multiple Signals in Sage Grouse: An Experiment with a Robotic Female. Behav. Ecol. 2010, 21, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, P.; Collins, K. Assessing conspecific aggression in fighting dogs. In Proceedings of the AVSAB/ACVB Meeting, San Diego, CA, USA, 3 August 2012; pp. 37–39. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, S.; Siracusa, C.; Reisner, I.; Valsecchi, P.; Serpell, J.A. Validity of model devices used to assess canine temperament in behavioral tests. Appl Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 138, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabelansky, A.; Dowling-Guyer, S.; Quist, H.; D’Arpino, S.S.; McCobb, E. Consistency of shelter dogs’ behavior toward a fake versus real stimulus dog during a behavior evaluation. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 163, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, I.; Serpell, J.A.; Alvarez, C.E. Genetic mapping of canine fear and aggression. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackwell, E.J.; Bradshaw, J.W.; Casey, R.A. Fear responses to noises in domestic dogs: Prevalence, risk factors and co-occurrence with other fear related behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2013, 145, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overall, K.L.; Hamilton, S.P.; Lee Chang, M. Understanding the Genetic Basis of Canine Anxiety: Phenotyping Dogs for Behavioral, Neurochemical, and Genetic Assessment. J. Vet. Behav. 2006, 1, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, M.; Ottobre, J.; Ottobre, A.; Neville, P.; St-Pierre, N.; Dreschel, N.; Pate, J.L. Breed-Dependent Differences in the Onset of Fear-Related Avoidance Behavior in Puppies. J. Vet. Behav. 2015, 10, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, T.J.; King, T.; Bennett, P.C. Puppy parties and beyond: The role of early age socialization practices on adult dog behavior. Vet. Med. Res. Rep. 2015, 6, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seksel, K.; Mazurski, E.J.; Taylor, A. Puppy socialisation programs: Short and long term behavioural effects. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1999, 62, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaterlaws-Whiteside, H.; Hartmann, A. Improving puppy behavior using a new standardized socialization program. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 197, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluijmakers, J.J.; Appleby, D.L.; Bradshaw, J.W. Exposure to video images between 3 and 5 weeks of age decreases neophobia in domestic dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2010, 126, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Breed | Female | Male | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| American Cocker Spaniel | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Australian Shepherd | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Bernese Mountain Dog | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Bichon Frise | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Boston Terrier | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Boxer | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Bullmastiff | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Cavalier King Charles Spaniel | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| French Bulldog | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Golden Retriever | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Great Dane | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Havanese | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Lhasa Apso | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Maltese | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Miniature Schnauzer | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Neopolitan Mastiff | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Pomeranian | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Saint Bernard | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Samoyed | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Shiba Inu | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Shih Tzu | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Siberian Husky | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Standard Poodle | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Toy Poodle | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Yorkshire Terrier | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Grand Total | 45 | 15 | 60 |

| Category | Behavior | Definition | Type of Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fear | Escaping † | Moving to back or front exit, pawing at door or ground near door | Duration |

| Freezing † | Dog stops movement or sound, body still, muscle tension, possibly in a lowered or stiff/rigid posture | Duration | |

| Retreat † | Dog moves away from the stimulus with lowered posture (possibly tail tucked, ears back, body lowered to ground) after investigation | Duration | |

| Gaze avoidance | Dog continually looks at and looks away from stimulus | Duration | |

| Stress | Yawning † | Opening mouth wide, no noise generated, could be repetitive | Frequency |

| Paw-lifting | Raising paw off the ground and maintaining for a short period of time | Frequency | |

| Shivering † | Entire body is shaking; could be in a lowered posture (possibly tail tucked, ears back) | Duration | |

| Lip-licking | Tongue repeatedly moving around the outside of the mouth | Frequency | |

| Body shake † | Rapid shake of body from head to tail | Frequency | |

| Aggression | Biting/Snapping † | Opening mouth and showing teeth and quickly closing, could be snapping at the air | Frequency |

| Teeth baring † | Lips raised showing teeth, could include growling or snarling | Frequency | |

| Stereotypic | Pacing † | Dog walking from side to side of kennel in a repetitive manner (at least 3 times) | Duration |

| Circling † | Dog moving in circles around themselves or an object in a repetitive manner (at least 3 times) | Duration | |

| Activity | Standing 1 | Dog is on all four legs, not moving | Duration |

| Sniffing 1 | nose on or toward stimulus, mouth closed, breathing rapidly | Duration | |

| Lying | Dog is flat on the ground, head can be up or also on the ground, back and tail in neutral position for breed | Duration | |

| Walking | Dog moving around pen with neutral back and tail positions for breed | Duration | |

| Sitting 1 | Dog back legs are tucked under body, front legs vertical | Duration | |

| Standing on hind legs | Dog is standing on back legs with front legs in the air or leaning against the wall | Duration | |

| Non-fearful | Stimulus directed play | Any of the following in combination: tail wagging, ears perked, sniffing/licking/pawing stimulus, moving stimulus, play mouthing, play bow | Duration |

| Affiliative approach to tester | Dog moves toward tester with a loose body posture, tail high or low, tail possibly wagging, ears possibly perked, possibly sniffing tester or air near tester | Duration | |

| Vocalization | Bark | Quick and possibly repetitive vocalizations | Frequency |

| Whine † | Higher-pitched vocalization | Frequency | |

| Growl † | Lower-pitched grumble vocalization, may have teeth showing | Frequency | |

| Other | Investigating environment | Sniffing/licking the floor or pen walls (not directed toward stimulus) | Duration |

| Elimination † | Dog urinates, defecates, or vomits on the pen floor | Frequency | |

| Tester contact/No contact | Tester was able/unable to make contact with the dog during the approach test | Frequency | |

| Takes treat | Dog accepts treat from tester or from the floor | Frequency | |

| Latency to approach and interact with stimulus | Time elapsed from the start of the test to the dog approaching either the tester or the object | Duration | |

| Posture Modifiers | Lowered | head lowered, ears pinned back, center of body lowered, tail tucked | N/A |

| Neutral | head normal to raised, ears forward, tail high or normal for breed | ||

| Rigid | head high, ears forward, tail high, mouth tight, muscles tensed |

| Behavior | ICC | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||

| Gaze avoidance | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.99 |

| Investigating environment | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.99 |

| Stimulus directed play | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.99 |

| Sitting | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.99 |

| Sniffing | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.99 |

| Standing | 0.72 | 0.39 | 0.87 |

| Walking | 0.77 | 0.49 | 0.89 |

| Lowered posture | 0.82 | 0.60 | 0.92 |

| Neutral posture | 0.79 | 0.53 | 0.90 |

| Rigid posture | 0.87 | 0.71 | 0.94 |

| Lying | 0.89 | 0.76 | 0.95 |

| Standing on hind legs | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Affiliative approach to tester | 0.74 | 0.43 | 0.88 |

| Latency to approach and interact | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.98 |

| Takes treat | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.98 |

| Tester contact/No contact | 1.000 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Stress-related | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.99 |

| Behavior | Red | Yellow | Green |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaze avoidance | 4.67 | 3.62 | 1.35 |

| Investigate environment | 4.59 | 3.63 | 6.81 |

| Stimulus directed play | 0 | 0 | 0.11 |

| Lying | 0.85 | 0.39 | 0.44 |

| Standing on hind legs | 0 | 0 | 0.77 |

| Retreat | 0.75 | 1.16 | 0.38 |

| Sitting | 9.75 | 5.66 | 4.85 |

| Sniffing | 1.68 | 2.41 | 4.85 |

| Standing | 10.99 | 8.94 | 7.29 |

| Walking | 4.66 | 7.10 | 12.16 |

| Latency to approach and interact with the stimulus | 20.74 | 16.03 | 6.75 |

| Lowered posture | 15.38 | 9.47 | 5.36 |

| Neutral posture | 3.29 | 2.30 | 8.78 |

| Rigid posture | 3.75 | 5.25 | 1.92 |

| Stress-related | 0.23 | 0.36 | 0.28 |

| Behavior | Red | Yellow | Green |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaze avoidance | 2.66 | 1.57 | 1.44 |

| Investigate environment | 0.58 | 1.05 | 1.24 |

| Stimulus directed play | 0 | 0 | 0.69 |

| Lying | 0 | 0.09 | 0.22 |

| Standing on hind legs | 0 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| Retreat | 0.89 | 0.82 | 0.95 |

| Sitting | 2.50 | 0 | 1.38 |

| Sniffing | 15.95 | 17.72 | 16.67 |

| Standing | 6.21 | 5.97 | 4.39 |

| Walking | 8.72 | 9.12 | 5.01 |

| Latency to approach and interact with the stimulus | 5.64 | 1.06 | 1.74 |

| Lowered posture | 15.52 | 15.45 | 7.16 |

| Neutral posture | 0.54 | 1.77 | 7.33 |

| Rigid posture | 8.60 | 6.46 | 7.95 |

| Stress-related | 0.54 | 0.36 | 0.61 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pritchett, M.; Barnard, S.; Croney, C. Socialization in Commercial Breeding Kennels: The Use of Novel Stimuli to Measure Social and Non-Social Fear in Dogs. Animals 2021, 11, 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11030890

Pritchett M, Barnard S, Croney C. Socialization in Commercial Breeding Kennels: The Use of Novel Stimuli to Measure Social and Non-Social Fear in Dogs. Animals. 2021; 11(3):890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11030890

Chicago/Turabian StylePritchett, Margaret, Shanis Barnard, and Candace Croney. 2021. "Socialization in Commercial Breeding Kennels: The Use of Novel Stimuli to Measure Social and Non-Social Fear in Dogs" Animals 11, no. 3: 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11030890

APA StylePritchett, M., Barnard, S., & Croney, C. (2021). Socialization in Commercial Breeding Kennels: The Use of Novel Stimuli to Measure Social and Non-Social Fear in Dogs. Animals, 11(3), 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11030890