Dropping the Ball? The Welfare of Ball Pythons Traded in the EU and North America

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Exotic Pet Expositions

- -

- Time of observation.

- -

- Vendor name (which was subsequently anonymous) for each stall selling Ball pythons (if advertised).

- -

- Total number of Ball pythons on display at each stall.

- -

- Number of snakes in each enclosure.

- -

- Environmental enrichment such as branches provided (Y/N) for each enclosure.

- -

- Whether the enclosure was transparent (Y/N).

- -

- Substrate type (if present) for each enclosure.

- -

- Ball python husbandry information provided by vendor via leaflets (Y/N).

- -

- Whether the Ball python was a “morph” (Y/N).

2.2. YouTube Videos

- -

- The number of Ball pythons observed in each enclosure.

- -

- Whether the enclosure was provided with environmental enrichment (e.g., branches) (Y/N).

- -

- Whether or not the enclosure was transparent (Y/N).

- -

- Substrate type (if present) for each enclosure.

- -

- An estimate of the total number of enclosures observed in each video.

- -

- Whether or not the Ball python was a morph (Y/N).

2.3. Educational Information: On-Line Review

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Exotic Pet Expositions

3.2. YouTube Videos

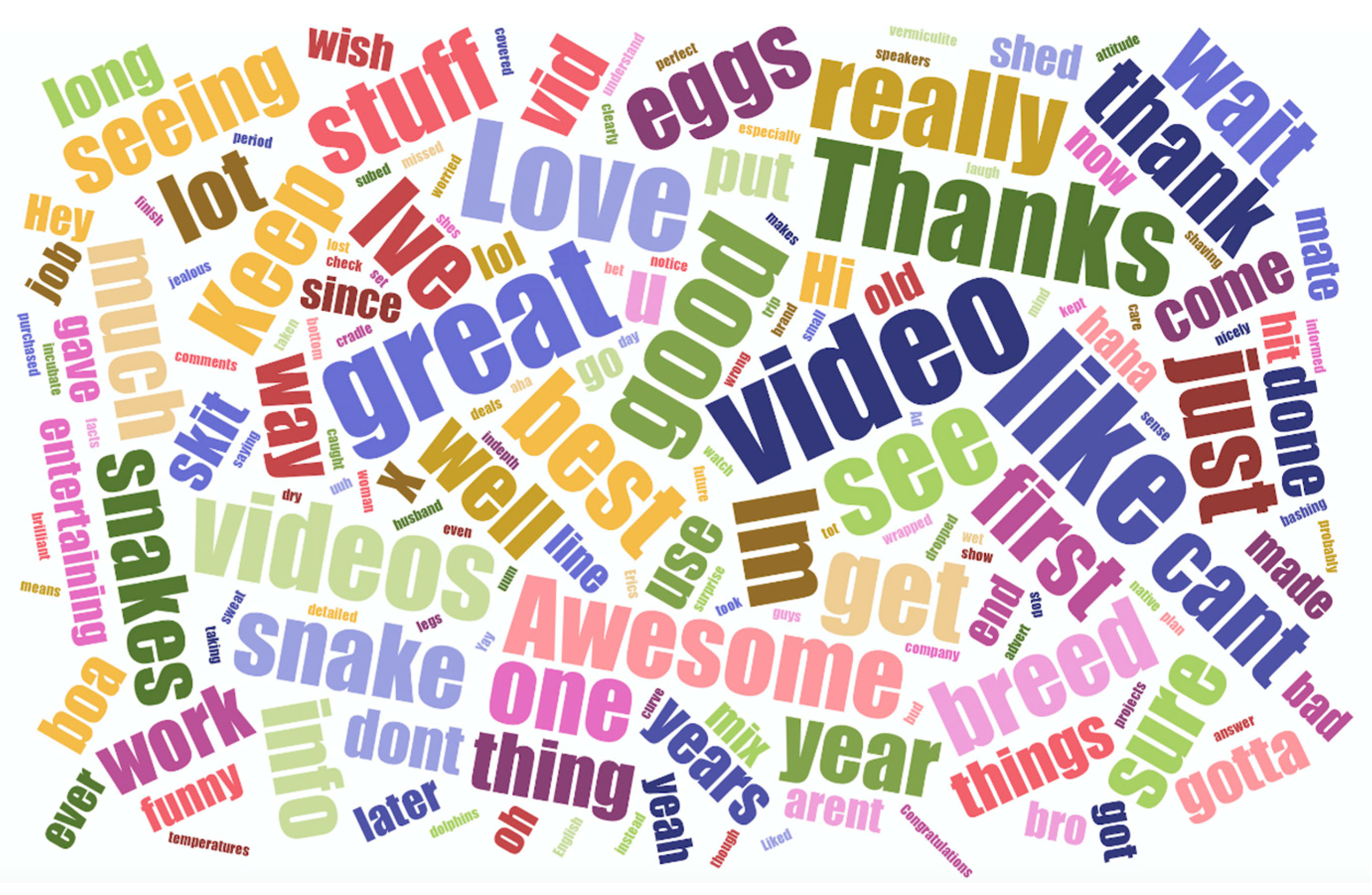

3.3. Educational Information Online

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Mobility

4.3. Shelter and Water

4.4. Hygiene and Substrate

4.5. Duration and Purpose of Captivity

4.6. Selectively Bred Morphs

4.7. Education and Consumer Awareness

5. Limitations

6. Recommendations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Driscoll, C.A.; Macdonald, D.W. Top dogs: Wolf domestication and wealth. J. Biol. 2010, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Neer, W.; Linseele, V.; Friedma, R. More animal burials from the Predynastic elite cemetery of Hierakonpolis (Upper Egypt): The 2008 season. In Archaeozoology of the Near East; Mashkour, M., Beech, M., Eds.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2017; Volume 9, pp. 388–403. [Google Scholar]

- Podberscek, A.L.; Paul, E.S.; Serpell, J.A. Companion Animals and Us: Exploring the Relationships between People and Pets; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Can, O.E.; D’Cruze, N.; Macdonald, D.W. Dealing in deadly pathogens taking stock of the legal trade in live wildlife and potential risks to human health. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, E.R.; Baker, S.E.; Macdonald, D.W. Global trade in exotic pets 2006–2012. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 28, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, M.; Tully, T.N., Jr. Manual of Exotic Pet Practice; Elsevier Health Sciences: Maryland Heights, MO, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Honegger, R.E. Threatened Amphibians and Reptiles in Europe; Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Importance of Freshwater Fishes; International Union for Conservation of Nature: Grand, Swiss, 2011; Available online: http://www.iucnffsg.org/freshwater-fishes/importance-of-freshwater-fishes/ (accessed on 9 February 2018).

- Yan, G. Saving Nemo e Reducing mortality rates of wild-caught ornamental fish. Live Reef Fish Inf. Bull 2016, 21, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Biondo, M.V. Quantifying the trade in marine ornamental fishes into Switzerland and an estimation of imports from the European Union. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2017, 11, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, M.; Pütsch, M.; Bisschopinck, T. Transport Mortality during the Import of Wild Caught Birds and Reptiles to Germany; F+E-Vorhaben, German Federal Agency for Nature Conservation: Bonn, Germany, 1998; p. 110. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, S.E.; Cain, R.; Van Kesteren, F.; Zommers, Z.A.; D’Cruze, N.; Macdonald, D.W. Rough trade: Animal welfare in the global wildlife trade. BioScience 2013, 63, 928–938. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.E.; St. John, F.A.V.; Griffiths, R.A.; Roberts, D.L. Captive reptile mortality rates in the home and implications for the wildlife trade. PLoS ONE. 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toland, E.; Warwick, C.; Arena, P.C. The exotic pet trade: Pet hate. Biologist 2012, 59, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Arena, P.; Steedman, C.; Warwick, C. Amphibian and Reptile Pet Markets in the EU an Investigation and Assessment; Animal Protection Agency, Animal Public, International Animal Rescue, Eurogroup for Wildlife and Laboratory Animals, Fundación para la Adopción, el Apadrinamiento y la Defensa de los Animales: London, UK, 2012; 52 p. [Google Scholar]

- Warwick, C.; Arena, P.C.; Steedman, C. Visitor behaviour and public health implications associated with exotic pet markets: An observational study. J. R. Soc. Med. Short Rep. 2012, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altherr, S. Stolen Wildlife—Why the EU Needs to Tackle Smuggling of Nationally Protected Species; Pro Wildlife: Munich, Germany, 2014; p. 32. Available online: https://www.prowildlife.de/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/2014_Stolen-Wildlife-Report.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Harrington, L.A.; Macdonald, D.W.; D’Cruze, N. Popularity of pet otters on YouTube: Evidence of an emerging trade threat. Nat. Conserv. 2019, 36, 17–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekaris, K.A.I.; Campbell, N.; Coggins, T.G.; Rode, E.J.; Nijman, V. Tickled to death: Ana¬lysing public perceptions of “cute’ videos of threatened species (slow lorises—Nycticebus spp.) on Web 2.0 sites. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diehl, T.; Weeks, B.E.; Gil de Zuniga, H. Political persuasion on social media: Tracing direct and indirect effects of news use and social interaction. New Media Soc. 2016, 18, 1875–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Cruze, N.; Harrington, L.; Délagnon, P.; Green, J.; Macdonald, D.W.; Ronfot, D.; Segniagbeto, G.H.; Auliya, M. Betting the Farm: A Review of Ball Python Trade from Togo, West Africa. Nat. Conserv. in press.

- Auliya, M.; Schmitz, A. Python regius. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-4.RLTS.T177562A7457411.en (accessed on 22 February 2018).

- Gorzula, S.; Nsiah, W.O.; Oduro, W. Survey of the Status and Management of the Royal Python (Python Regius) in Ghana. Part 1. Report to the Secretariat of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES); Wildlife Department: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997; pp. 1–38. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/cites/pdf/studies/royal_python_ghana.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Jenkins, R.W.G. Management and Use of Python Regius in Benin and Togo (p. 11); CITES Animal Committee; IUCN/SSC: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, M.; Williams, D. Neurological dysfunction in a ball python (Python regius) colour morph and implications for welfare. J. Exot. Pet. Med. 2014, 23, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RSPCA Royal Python Care Sheet. 2018. Available online: https://www.rspca.org.uk/adviceandwelfare/pets/other/royalpython?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIo7r8mZP73AIV65XtCh1jvgcpEAAYASAAEgKlp_D_BwE (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Warwick, C.; Frye, F.L.; Murphy, J.B. Introduction: Health and welfare of captive reptiles. In Health and Welfare of Captive Reptiles; Warwick, C., Frye, F.L., Eds.; Chapman & Hall/Kluwer: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Warwick, C.; Jessop, M.; Arena, P.; Pilny, A.; Steedman, C. Guidelines for inspection of companion and commercial animal establishments. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warwick, C.; Arena, P.; Steedman, C. Spatial considerations for captive snakes. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2019, 30, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuur, A.; Ieno, E.N.; Walker, N.; Saveliev, A.A.; Smith, G.M. Mixed Effects Models and Extensions in Ecology with R; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Home Range, Habitat Use, and Movement Patterns of Non-Native Burmese Pythons in Everglades National Park, Florida, USA. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40317-015-0022-2 (accessed on 2 March 2020).

- Auliya, M.; Hofmann, S.; Segniagbeto, G.H.; Assou, D.; Ronfot, D.; Astrin, J.J.; Forat, S.; Ketoh, G.K.K.; D’Cruze, N. The first genetic assessment of wild and farmed Ball pythons (Reptilia: Serpentes: Pythonidae) in Togo. Nat. Conserv. in press.

- NSW. Code of Practice for the Keeping of Reptiles. State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage; Office of Environment and Heritage: Sydney South, NSW, Australia, 1232; 2013. Available online: https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/-/media/OEH/Corporate-Site/Documents/Licences-and-permits/keeping-private-reptiles-code-of-practice.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- The Animal Welfare (Licensing of Activities Involving Animals) (England) Regulations 2018 Guidance Notes for Conditions. DEFRA. 2018. Available online: http://www.cfsg.org.uk/_layouts/15/start.aspx#/sitepages/legislation%20and%20guidance.aspx (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Kaplan, M. Anapsid Emaciation (Starvation) Protocol. 2014. Available online: http://www.anapsid.org/emaciation.html (accessed on 6 May 2018).

- Divers, S.J. Management of Reptiles. MSD Veterinary Manual. 2018. Available online: https://www.msdvetmanual.com/exotic-and-laboratory-animals/reptiles/management-of-reptiles (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Astley, H.C.; Jayne, B.C. Effects of perch diameter and incline on the kinematics, performance and modes of arboreal locomotion of corn snakes (Elaphe guttata). J. Exp. Biol. 2007, 210, 3862–3872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BVZS. Pet Shop Inspection Guidance Notes; British Veterinary Zoological Society: London, UK, 2014; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, S.L. Reptile Wellness Management. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Exot. Anim. Pract. 2015, 18, 281–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreger, M.D.; Mench, J.A. Physiological and behavioral effects of handling and restraint in the ball python (Python regius) and the blue-tongued skink (Tiliqua scincoides). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1993, 38, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, T.M. David. G. Ball Pythons: Their History, Natural History, Care and Breeding; VPI Library: Boerne, TX, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Warwick, C.; Arena, P.C.; Lindley, S.; Jessop, M.; Steedman, C. Assessing reptile welfare using behavioural criteria. Practice 2013, 35, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broghammer, S. Python Regius, Atlas of Colour Morphs, Keeping and Breeding, 2nd ed.; Natur und Tier-Verlag: Münster, Germany, 2019; p. 440. [Google Scholar]

- Cundall, D. Drinking in snakes: Kinematic cycling and water transport. J. Expl Biol. 2000, 203, 2171–2185. [Google Scholar]

- TRAFFIC. Captive Bred, or Wild Taken? TRAFFIC International: Cambridge, UK, 2012; Available online: https://www.traffic.org/site/assets/files/7446/captive-bred-or-wild-taken.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Ashley, S.; Brown, S.; Ledford, J.; Martin, J.; Nash, A.E.; Terry, A.; Tristan, T.; Warwick, C. Morbidity and mortality of invertebrates, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals at a major exotic companion animal wholesaler. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2014, 17, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warwick, C. Captive Breeding-Saving Wildlife? Or Saving the Pet Trade? The Ecologist. 2015. Available online: http://www.theecologist.org/News/news_analysis/2985202/captive_breeding_saving_wildlife_or_saving_the_pet_trade.html (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Bennett, R.A.; Mehler, S.J. Neurology, in Mader DR (Ed): Reptile Medicine and Surgery (Ed 1); Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2006; pp. 239–250. [Google Scholar]

- Broom, D.M.; Johnson, K.G. Assessing Welfare: Short-Term Responses. In Stress and Animal Welfare; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 87–110. [Google Scholar]

- Warwick, C. Reptilian ethology in captivity: Observations of some problems and an evaluation of their aetiology. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1990, 26, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warwick, C. Psychological and behavioural principles and problems. In Health and Welfare of Captive Reptiles; Warwick, C., Frye, F.L., Eds.; Chapman & Hall/Kluwer: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- OWAL Reptiles. Morph Issues. Available online: http://owalreptiles.com/issues.php (accessed on 26 May 2018).

- Scherz, M. Duckbill Mutation in Snakes. 2018. Available online: https://markscherz.tumblr.com/post/84960749508/what-is-the-duckbill-mutation (accessed on 26 May 2018).

- Mendyk, R.W. Challenging folklore reptile husbandry in zoological parks. In Zoo Animals: Husbandry, Welfare and Public Interactions; Berger, M., Corbett, S., Eds.; Nova Science: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 265–292. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, H.; Carder, G.; D’Cruze, N. Given the Cold Shoulder: A Review of the Scientific Literature for Evidence of Reptile Sentience. Animals 2019, 9, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorhouse, T.P.; Balaskas, M.; D’Cruze, N.C.; Macdonald, D.W. Information Could Reduce Consumer Demand for Exotic Pets. Conserv. Lett. 2017, 10, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warwick, C. The Morality of the Reptile “Pet” Trade. J. Anim. Ethics 2014, 4, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Coulthard, E.; Megson, D.; Norrey, J.; Auliya, M.; D’Cruze, N. A Literature Review of Research Addressing the Welfare of Ball Pythons in the Exotic Pet Trade. in press. Animals 2020, 10, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Exposition Organiser | Location of Exposition | Date of Visit | No. Vendors | No. Snakes | No. Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madrid Expo Terraria | Madrid, Spain | 24.03.18 | 9 | 221 | 5 |

| Canadian Reptile Breeders’ Expo | Toronto, ON, Canada | 06.05.18 | 28 | 1245 | 2 |

| Terraria Houten | Houten, The Netherlands | 03.06.18 | 15 | 523 | 3 |

| Repticon Tampa | Tampa, FL, USA | 09 & 10.06.18 | 24 | 1078 | 4 |

| Repticon Deland | Deland, FL, USA | 16.06.18 | 7 | 286 | 3 |

| Expo Terra Doncaster | Doncaster, UK | 24.06.18 | 28 | 427 | 2 |

| Terraria Houten | Houten, The Netherlands | 23.09.18 | 31 | 1081 | 1 |

| No. | Category/Score | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mobility/Space | Length of enclosure = less than length of snake. | Length of enclosure = length of snake. | Length of enclosure = approx. 1.5 X length of snake. |

| 2 | Shelter | No shelters present. | Shelter present, which does not cover 100% of snake when coiled up. | Shelter present, which covers 100% of snake, when coiled up. |

| 3 | Water | No water present. | Clean water available. Water bowl is too small to allow the snake to soak its entire body. | Clean water available. Water bowl is large enough to allow the snake to soak its entire body. |

| 4 | Substrate | No substrate present (covers 0% of enclosure floor). | Inadequate substrate present (covers < 75% of enclosure floor). | Adequate substrate present (covers > 75% of enclosure floor) |

| 5 | Hygiene | Unacceptable level of hygiene. Detritus liberally present. | Intermediate between 1 and 3. | Acceptable level of hygiene. Detritus minimal present/absent. |

| Response Variable | Fixed Factor | Estimate | SE | T–Value | p–Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thumbs Up Score | Space | −1.207 | 1.056 | −1.143 | 0.256 |

| Shelter | 0.204 | 0.311 | 0.654 | 0.514 | |

| Water | 0.159 | 0.171 | 0.925 | 0.357 | |

| Substrate | −0.687 | 0.118 | −5.812 | <0.001 | |

| Hygiene | 0.502 | 0.132 | 3.802 | <0.001 | |

| Number of Snakes | 1.192 | 0.150 | 7.924 | <0.001 | |

| Transparency | 0.093 | 0.160 | 0.579 | 0.564 | |

| Thumbs Down Score | Space | 0.825 | 0.720 | 1.145 | 0.255 |

| Shelter | −0.994 | 1.205 | −0.825 | 0.411 | |

| Water | 0.068 | 0.328 | 0.208 | 0.835 | |

| Substrate | 0.025 | 0.224 | 0.112 | 0.911 | |

| Hygiene | −0.182 | 0.208 | −0.875 | 0.383 | |

| Number of Snakes | −0.168 | 0.294 | −0.572 | 0.568 | |

| Transparency | −0.658 | 0.311 | −2.117 | 0.037 | |

| Proportion of Positive Comments Within First 10 Videos | Space | −1.230 | 1.784 | −0.690 | 0.492 |

| Shelter | 0.020 | 0.329 | 0.062 | 0.951 | |

| Water | −0.099 | 0.416 | −0.237 | 0.813 | |

| Substrate | 0.119 | 0.339 | 0.350 | 0.720 | |

| Hygiene | 0.040 | 0.241 | 0.166 | 0.869 | |

| Number of Snakes | −0.306 | 0.282 | −1.088 | 0.279 | |

| Transparency | −0.363 | 0.289 | −1.255 | 0.212 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Cruze, N.; Paterson, S.; Green, J.; Megson, D.; Warwick, C.; Coulthard, E.; Norrey, J.; Auliya, M.; Carder, G. Dropping the Ball? The Welfare of Ball Pythons Traded in the EU and North America. Animals 2020, 10, 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10030413

D’Cruze N, Paterson S, Green J, Megson D, Warwick C, Coulthard E, Norrey J, Auliya M, Carder G. Dropping the Ball? The Welfare of Ball Pythons Traded in the EU and North America. Animals. 2020; 10(3):413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10030413

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Cruze, Neil, Suzi Paterson, Jennah Green, David Megson, Clifford Warwick, Emma Coulthard, John Norrey, Mark Auliya, and Gemma Carder. 2020. "Dropping the Ball? The Welfare of Ball Pythons Traded in the EU and North America" Animals 10, no. 3: 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10030413

APA StyleD’Cruze, N., Paterson, S., Green, J., Megson, D., Warwick, C., Coulthard, E., Norrey, J., Auliya, M., & Carder, G. (2020). Dropping the Ball? The Welfare of Ball Pythons Traded in the EU and North America. Animals, 10(3), 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10030413