Evaluation of Plant Origin Essential Oils as Herbal Biocides for the Protection of Caves Belonging to Natural and Cultural Heritage Sites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples Collection and Isolation of Microorganisms

2.2. Molecular Characterization

2.2.1. DNA Extraction

2.2.2. PCR Amplification

2.2.3. Electrophoresis, Quantification and Purification of PCR Products

2.2.4. Sequencing of Isolates

2.3. Essential Oils

2.4. Preparation of the Inocula

2.4.1. Preparation of the Bacterial Inocula

2.4.2. Preparation of the Fungal Inocula

2.5. Screening of the 18 EOs Antimicrobial Activity

2.6. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Non-Inhibitory Concentration (NIC) of the Most Effective EOs

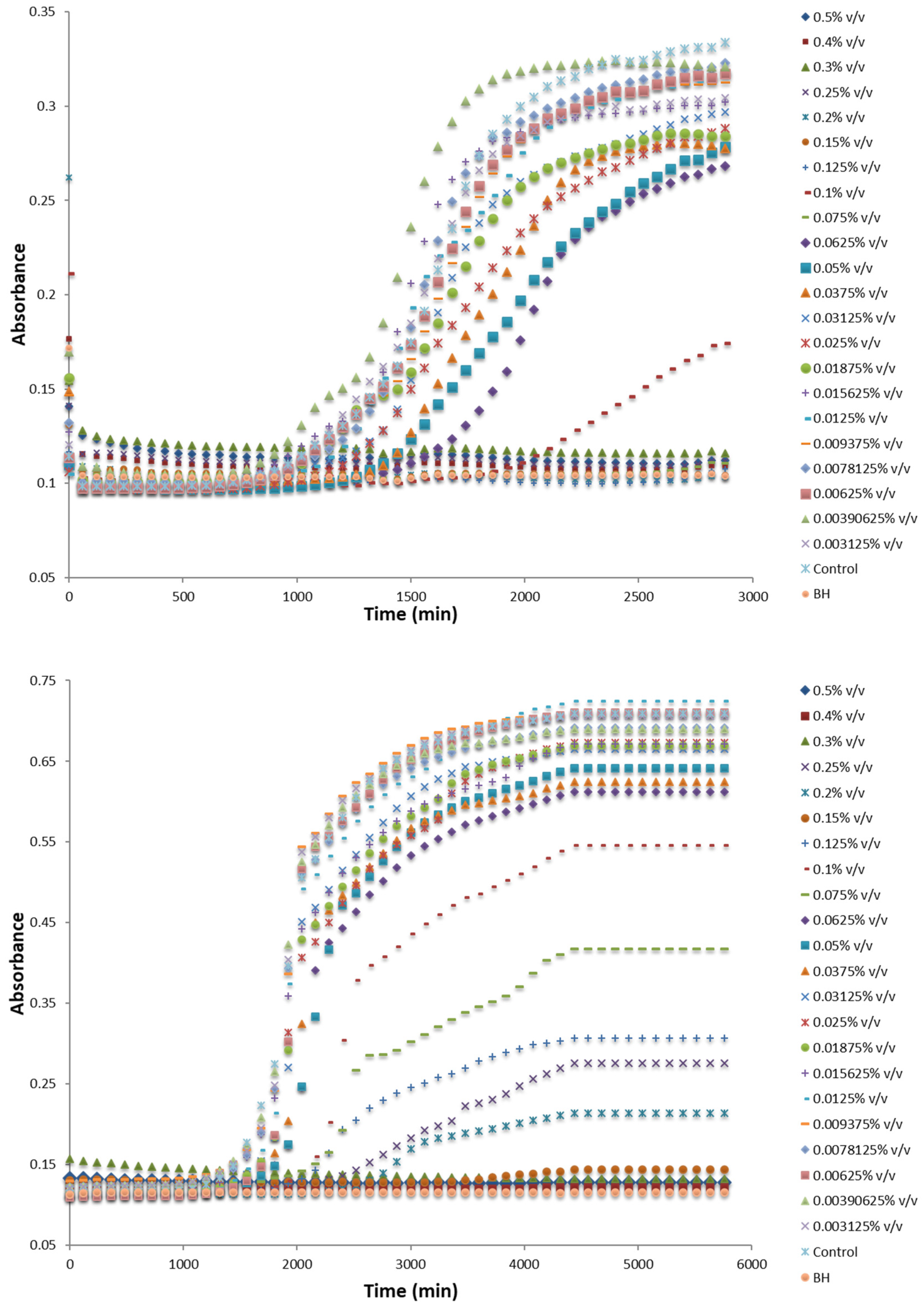

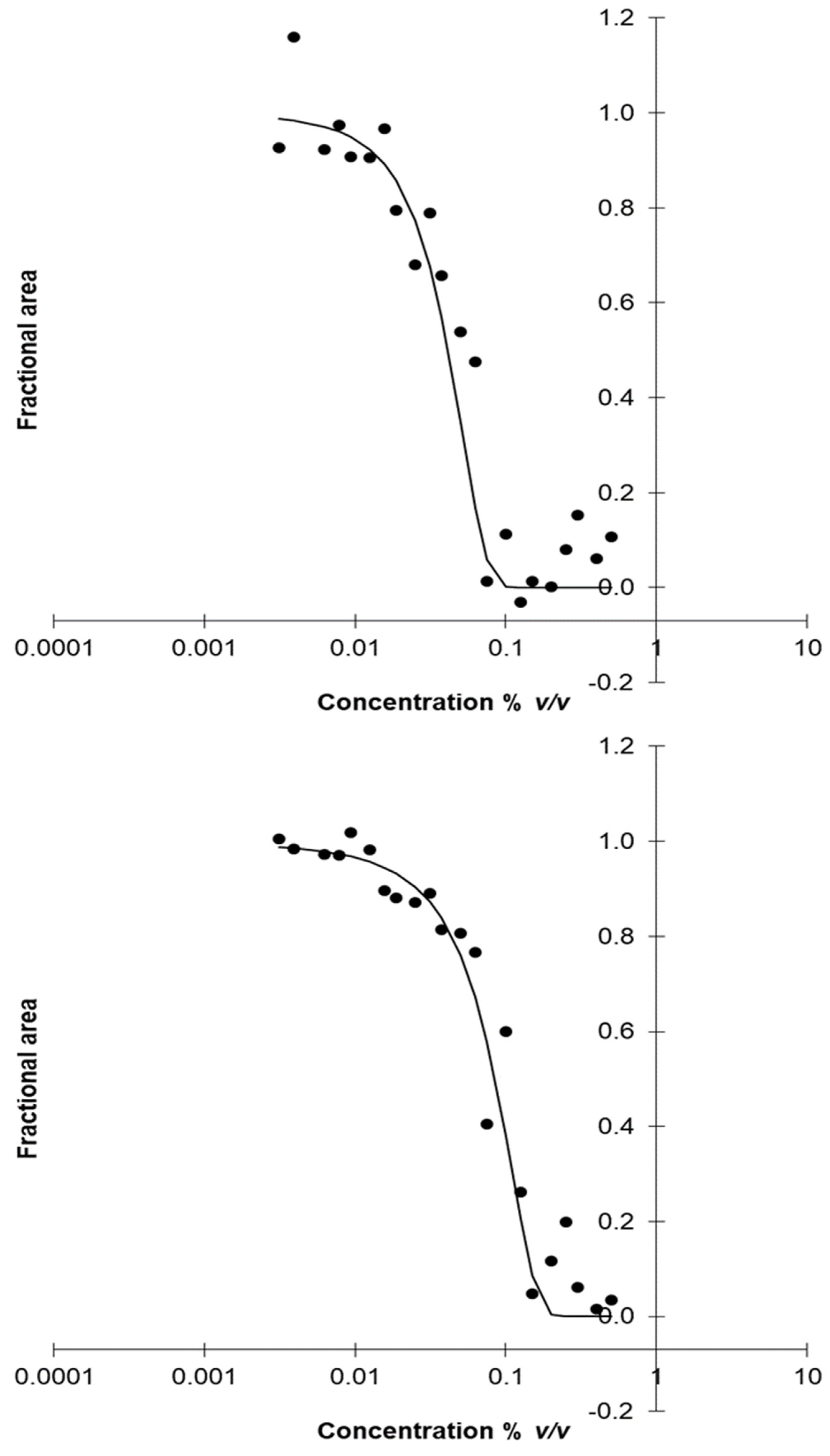

2.7. MIC and NIC Calculation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microorganisms

3.2. Antimicrobial Activity of the 18 EOs

3.3. MIC and NIC of the Most Effective EOs

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pfendler, S.; Karimi, B.; Alaoui-Sosse, L.; Bousta, F.; Alaoui-Sossé, B.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Aleya, L.S. Assessment of fungi proliferation and diversity in cultural heritage: Reactions to UV-C treatment. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 647, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.-Z.; Zhang, Z.-F.; Zhou, N.; Jiang, C.-Y.; Wang, B.-J.; Cai, L.; Liu, S.-J. Diversity, Distribution and Co-occurrence Patterns of Bacterial Communities in a Karst Cave System. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomczyk-Żak, K.; Zielenkiewicz, U. Microbial diversity in caves. Geomicrobiol. J. 2016, 33, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.L.S.; Resende-Stoianoff, M.A.R.; Lopes Ferreira, R. Mycological study for a management plan of a neotropical show cave (Brazil). Int. J. Speleol. 2013, 42, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamprinou, V.; Danielidis, D.B.; Pantazidou, A.; Oikonomou, A.; Economou-Amilli, A. The show cave of Diros vs wild caves of Peloponnese, Greece-distribution patterns of Cyanobacteria. Int. J. Speleol. 2014, 43, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, H.A. Introduction to cave microbiology: A review for the non-specialis. J. Caves Karst Stud. 2006, 68, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, H.A.; Northup, D.E. Geomicrobiology in cave environments: Past, current and future perspectives. J. Caves Karst Stud. 2007, 69, 163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Saiz-Jimenez, C. Microbiological and environmental issues in show caves. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 28, 2453–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adetutu, E.M.; Thorpe, K.; Shahsavari, E.; Bourne, S.; Cao, X.; Fard, R.M.N.; Kirby, G.; Ball, A.S. Bacterial community survey of sediments at Naracoorte Caves, Australia. Int. J. Speleol. 2012, 41, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, S.; Simić, G.S.; Stupar, M.; Unković, N.; Predojević, D.; Jovanović, J.; Grbić, M.L. Cyanobacteria, algae and microfungi present in biofilm from Božana Cave (Serbia). Int. J. Speleol. 2015, 44, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Urzì, C.; De Leo, F.; Bruno, L.; Albertano, P. Microbial diversity in Paleolithic caves: A study case on the phototrophic biofilms of the Cave of Bats (Zuheros, Spain). Microb. Ecol. 2010, 60, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseschart, A.; Mhuantong, W.; Tangphatsornruang, S.; Chantasingh, D.; Pootanakit, K. Shotgun metagenomic sequencing from Manao-Pee cave, Thailand, reveals insight into the microbial community structure and its metabolic potential. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfendler, S.; Karimi, B.; Maron, P.-A.; Ciadamidaro, L.; Valot, B.; Bousta, F.; Alaoui-Sosse, L.; Alaoui-Sosse, B.; Aleya, L. Biofilm biodiversity in French and Swiss show caves using the metabarcoding approach: First data. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderwolf, K.J.; Malloch, D.; McAlpine, D.F.; Forbes, G.J. A world review of fungi, yeasts, and slime molds in caves. Int. J. Speleol. 2013, 42, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitova, M.M.; Iliev, M.; Nováková, A.; Gorbushina, A.A.; Groudeva, V.I.; Martin-Sanchez, P.M. Diversity and biocide susceptibility of fungal assemblages dwelling in the Art Gallery of Magura Cave, Bulgaria. Int. J. Speleol. 2017, 46, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, A.S.; Stern, L.A.; Bennett, P.C. Microbial contributions to cave formation: New insights into sulfuric acid speleogenesis. Geology 2004, 32, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañaveras, J.C.; Cuezva, S.; Sanchez-Moral, S.; Lario, J.; Laiz, L.; Gonzales, J.M.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. On the origin of fiber calcite crystals in moonmilk deposits. Naturwissenschaften 2006, 93, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, B.; Wang, H.; Xiang, X.; Wang, R.; Yun, Y.; Gong, L. Phylogenetic diversity of culturable fungi in the Heshang Cave, central China. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañaveras, J.C.; Sanchez-Moral, S.; Sloer, V.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. Microorganisms and Microbially Induced Fabrics in Cave Walls. Geomicrobiol. J. 2001, 18, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakakhel, M.A.; Wu, F.; Gu, J.D.; Feng, H.; Shah, K.; Wang, W. Controlling biodeterioration of cultural heritage objects with biocides: A review. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2019, 143, 104721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, J.; Kiyuna, T.; Nishijima, M.; An, K.-D.; Nagatsuka, Y.; Tazato, N.; Handa, Y.; Hata-Tomita, J.; Sato, Y.; Kigawa, R.; et al. Polyphasic insights into the microbiomes of the Takamatsuzuka Tumulus and Kitora Tumulus. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 63, 63–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo, M.C.; Gonzalez, J.M.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. Metabolically active microbial communities of yellow and gray colonizations on the walls of Altamira Cave. Spain. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 104, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo, M.C.; Saiz-Jimenez, C.; Gonzalez, J.M. Molecular characterization of total and metabolically active bacterial communities of “white colonizations” in the Altamira Cave, Spain. Res. Microbiol. 2009, 160, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, J.; Gonzalez, J.M.; Ludwig, W.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. Detection and phylogenetic relationships of a highly diverse uncultured acidobacterial community on paleolithic paintings in Altamira Cave using 23S rRNA sequence analyses. Geomicrobiol. J. 2005, 22, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, L.; Creuzé-des-Châtelliers, C.; Trabac, T.; Dubost, A.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y.; Pommier, T. Rock substrate rather than black stain alterations drives microbial community structure in the passage of Lascaux Cave. Microbiome 2018, 6, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastian, F.; Jurado, V.; Nováková, A.; Alabouvette, C.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. The microbiology of Lascaux Cave. Microbiology 2010, 156, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogórek, R. Fungal Communities on Rock Surfaces in Demänovská Ice Cave and Demänovská Cave of Liberty (Slovakia). Geomicrobiol. J. 2018, 35, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterflinger, K. Fungi as geologic agents. Geomicrobiol. J. 2000, 17, 97–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadd, G.M. Geomycology: Biogeochemical transformations of rocks, minerals, metals and radionuclides by fungi, bioweathering and bioremediation. Mycol. Res. 2007, 111, 3–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, F.; Micheletti, E.; Bruno, L.; Adhikary, S.P.; Albertano, P.; De Philippis, R. Characteristics and role of the exocellular polysaccharides produced by five cyanobacteria isolated from phototrophic biofilms growing on stone monuments. Biofouling J. Bioadhesion Biofilm Res. 2012, 28, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskar, S.; Baskar, R.; Tewari, V.C.; Thorseth, I.H.; Øvreås, L.; Lee, N.M.; Routh, J. Cave Geomicrobiology in India: Status and prospects stromatolites. In Stromatolites: Interaction of microbes with sediments; Tewari, V., Seckbach, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 541–569. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, S.; Joshi, S.R. Insights into Cave Architecture and the Role of Bacterial Biofilm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 83, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, C. Wanted: Solution for cave mold. Science 2003, 300, 245. [Google Scholar]

- Dupont, J.; Jacquet, C.; Dennetiere, B.; Lacoste, S.; Bousta, F.; Orial, G.; Cruaud, C.; Couloux, A.; Roquebertet, M.-F. Invasion of the French paleolithic painted cave of Lascaux by members of the Fusarium solani species complex. Mycologia 2007, 99, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulec, J.; Kosi, G. Lampenflora algae and methods of growth control. J. Caves Karst Stud. 2009, 71, 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Patrauchan, M.A.; Oriel, P.J. Degradation of benzyldimethylalkylammonium chloride by Aeromonas hydrophila sp. K. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 94, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, F.; Alabouvette, C.; Jurado, V.; Saiz Jimenez, C. Impact of biocide treatments on the bacterial communities of the Lascaux Cave. Naturwissenschaften 2009, 96, 863–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, M.; Mitova, M.; Ilieva, R.; Groudeva, V.; Grozdanov, P. Bacterial isolates from rock paintings of magura cave and sensitivity to different biocides. Comptes Rendus L’Academie Bulg. Sci. 2018, 71, 640–647. [Google Scholar]

- Stupar, M.; Grbić, M.L.J.; Džamić, A.; Unković, N.; Ristić, M.; Jelikić, A.; Vukojević, J. Antifungal activity of selected essential oils and biocide benzalkonium chloride against the fungi isolated from cultural heritage objects. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2014, 93, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrego, S.; Valdés, O.; Vivar, I.; Lavin, P.; Guiamet, P.; Battistoni, P.; Gómez de Saravia, S.; Borges, P. Essential Oils of Plants as Biocides against Microorganisms Isolated from Cuban and Argentine Documentary Heritage. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2012, 2012, 826786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, A.A.; Ghaly, M.F.; El-Sayed, F.; Abdel-Haliem, M. The efficacy of specific essential oils on yeasts isolated from the royal tomb paintings at Tanis, Egypt. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2012, 3, 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Veneranda, M.; Blanco-Zubiaguirre, L.; Roselli, G.; Di Girolami, G.; Castro, K.; Madariaga, J.M. Evaluating the exploitability of several essential oils constituents as a novel biological treatment against cultural heritage biocolonization. Microchem. J. 2018, 138, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, A.; Santos, S.; Caetano, J.; Pintado, M.; Vieira, E.; Moreira, P.R. Basil essential oil as an alternative to commercial biocides against fungi associated with black stains in mural painting. Build. Environ. 2020, 167, 106459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotolo, V.; De Caro, M.L.; Giordano, A.; Palla, F. Solunto archaeological park in Sicily: Life under mosaic tesserae. Fl. Medit. 2016, 28, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippka, R.; Deruelles, J.; Waterbury, J.B.; Herdman, M.; Stanier, R.Y. Generic assignments strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1979, 111, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J.; Hocking, A. Fungi and Food Spoilage; Blackie Academic and Professional: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenadić, M.; Ljaljević-Grbić, M.; Stupar, M.; Vukojević, J.; Ćirić, A.; Tešević, V.; Vujisić, L.; Todosijević, M.; Vesović, N.; Živković, N.; et al. Antifungal activity of the pygidial gland secretion of Laemostenus punctatus (Coleoptera: Carabidae) against cave-dwelling micromycetes. Die Nat. 2017, 104, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doulgeraki, A.I.; Danilo, E.; Villani, F.; Nychas, G.-J.E. Spoilage microbiota associated to the storage of raw meat in different conditions. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 157, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merrick, C.A.; Wardrope, C.; Paget, J.E.; Colloms, S.D.; Rosser, S.J. Rapid Optimization of Engineered Metabolic Pathways with Serine Integrase Recombinational Assembly (SIRA). Meth. Enzymol. 2016, 575, 285–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Madden, T.L.; Schäffer, A.A.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Miller, W.; Lipman, D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 3389–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorianopoulos, N.G.; Evergetis, E.T.; Aligiannis, N.; Mitakou, S.; Nychas, G.-J.E.; Haroutounian, S.A. Correlation between chemical composition of Greek essential oils and their antibacterial activity against food-borne pathogens. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2007, 2, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evergetis, E.; Bellini, R.; Balatsos, G.; Michaelakis, A.; Carrieri, M.; Veronesi, R.; Papachristos, D.P.; Puggioli, A.; Kapsaski-Kanelli, V.-N.; Haroutounian, S.A. From bio-prospecting to field assessment: The case of carvacrol rich essential oil as a potent mosquito larvicidal and repellent agent. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 6, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapsaski-Kanelli, V.N.; Evergetis, E.; Michaelakis, A.; Papachristos, D.P.; Myrtsi, E.D.; Koulocheri, S.D.; Haroutounian, S.A. “Gold” Pressed Essential Oil: An essay on the volatile fragment from citrus juice industry by-products chemistry and bioactivity. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 2761461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evergetis, E.; Michaelakis, A.; Papachristos, D.P.; Badieritakis, E.; Kapsaski-Kanelli, V.N.; Haroutounian, S.A. Seasonal variation and bioactivity of the essential oils of two Juniperus species against Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus (Skuse, 1894). Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 2175–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorianopoulos, N.; Lambert, R.J.; Skandamis, P.N.; Evergetis, E.T.; Haroutounian, S.A.; Nychas, G.J. A newly developed assay to study the minimum inhibitory concentration of Satureja spinosa essential oil. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 100, 77886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samson, R.A.; Hoekstra, E.S.; Frisvad, J.C. Introduction to Food and Airborne Fungi, 6th ed.; Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2000; p. 389. [Google Scholar]

- Abarca, M.L.; Bragulat, M.R.; Cabãnes, F.J. A new in vitro method to detect growth and ochratoxin A-producing ability of multiple fungal species commonly found in food commodities. Food Microbiol. 2014, 44, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, A.; Lambert RJ, W.; Magan, N. Rapid throughput analysis of filamentous fungal growth using turbidimetric measurements with the Bioscreen C: A tool for screening antifungal compounds. Fungal Biol. 2012, 116, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert RJ, W.; Pearson, J. Susceptibility testing: Accurate and reproducible minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and non-inhibitory concentration (NIC) values. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 88, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, R.J.; Lambert, R. A model for the efficacy of combined inhibitors. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 95, 73443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Paine, E.; Wall, R.; Kam, G.; Lauriente, T.; Sa-ngarmangkang, P.-C.; Horne, D.; Cheeptham, N. In Situ Cultured Bacterial Diversity from Iron Curtain Cave, Chilliwack, British Columbia, Canada. Diversity 2017, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarela, M.; Alakomi, H.-L.; Suihko, M.-L.; Maunuksela, L.; Raaska, L.; Mattila-Sandholm, T. Heterotrophic microorganisms in air and biofilm samples from Roman catacombs, with special emphasis on actinobacteria and fungi. Inter. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2004, 54, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Cortes, A.; Cuezva, S.; Sanchez-Moral, S.; Cañaveras, J.; Porca, E.; Jurado, V.; Martin-Sanchez, P.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. Detection of human-induced environmental disturbances in a show cave. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2011, 18, 1037–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikonja, B.H.; Tkavc, R.; Paši´c, L. Diversity of cultivable bacteria involved in the formation of macroscopic microbial colonies (cave silver) on the walls of a cave in Slovenia. Int. J. Speleol. 2014, 43, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowski, A.C.; Wang, W.; Koteva, K.; Barton, H.A.; McArthur, A.G.; Wright, G.D. A diverse intrinsic antibiotic resistome from a cave bacterium. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, M.J.; Maier, R.M.; Pryor, B.M. Fungal communities on speleothem surfaces in Kartchner caverns, Arizona. Int. J. Speleol. 2011, 40, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderwolf, K.J.; Malloch, D.; Ivanova, N.V.; McAlpine, D.F. Lack of cave-associated mammals influences the fungal assemblages of insular solution caves in eastern Canada. J. Caves Karst Stud. 2016, 78, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.F.; Liu, F.; Zhou, X.; Liu, X.Z.; Liu, S.J.; Cai, L. Culturable mycobiota from Karst caves in China, with descriptions of 20 new species. Pers. Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2017, 39, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.F.; Cai, L. Substrate and spatial variables are major determinants of fungal community in karst caves in Southwest China. J. Biogeogr. 2019, 46, 1504–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, V.; Porca, E.; Cuezva, S.; Fernandez-Cortes, A.; Sanchez-Moral, S.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. Fungal outbreak in a show cave. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 3632–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetutu, E.M.; Thorpe, K.; Bourne, S.; Cao, X.; Shahsavari, E.; Kirby, G.; Ball, A.S. Phylogenetic Diversity of Fungal Communities in Areas Accessible and Not Accessible to Tourists in Naracoorte Caves. Mycologia 2011, 103, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nováková, A. Microscopic fungi isolated from the Domica Cave system (Slovak Karst National Park, Slovakia). A review. Int. J. Speleol. 2009, 38, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paula, C.C.P.; Montoya, Q.V.; Rodrigues, A.; Bichuette, M.E.; Seleghim, M.H.R. Terrestrial filamentous fungi from Gruta do Catão (São Desidério, Bahia, Northeastern Brazil) show high levels of cellulose degradation. J. Caves Karst Stud. 2016, 78, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nováková, A.; Hubka, V.; Valinová, Š.; Kolařík, M.; Hillebrand-Voiculescu, A.M. Cultivable microscopic fungi from an underground chemosynthesis-based ecosystem: A preliminary study. Folia Microbiol. 2018, 63, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurado, V.; Fernandez-Cortes, A.; Cuezva, S.; Laiz, L.; Cañaveras, J.C.; Sanchez-Moral, S.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. The Fungal Colonisation of Rock-Art Caves: Experimental Evidence. Naturwissenschaften 2009, 96, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiz-Jimenez, C.; Miller, A.Z.; Martin-Sanchez, P.M.; Hernandez-Marine, M. Uncovering the origin of the black stains in Lascaux cave in France. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 3220–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mandal, S.; Sanga, Z.; Senthil Kumar, N. Metagenome sequencing reveals Rhodococcus dominance in Farpuk Cave, Mizoram, India, an Eastern Himalayan biodiversity hot spot region. Genome Announc. 2015, 3, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, A.S.; Porter, M.L.; Stern, L.A.; Quinlan, S.; Bennett, P.C. Bacterial diversity, and ecosystem function of filamentous microbial mats from aphotic (cave) sulfidic springs dominated by chemolithoautotrophic “Epsilonproteobacteria”. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2004, 51, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert RJ, W.; Skandamis, P.; Coote, P.J.; Nychas, G.-J.E. A study of the minimum inhibitory concentration and mode of action of oregano essential oil. thymol and carvacrol. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 91, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulluce, M.; Sokmen, M.; Daferera, D.; Agar, G.; Ozkan, H.; Kartal, N.; Polissiou, M.; Sokmen, A.; Sahin, F. In vitro antibacterial, antifungal and antioxidant activities of the essential oil and methanol extracts of herbal parts and callus cultures of Satureja hortensis L. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 3958–3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chorianopoulos, N.; Kalpoutzakis, E.; Aligiannis, N.; Mitaku, S.; Nychas, G.-J.E.; Haroutounian, S.A. Essential oils of Satureja, Origanum and Thymus species: Chemical composition and antibacterial activities against foodborne pathogens. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 8261–8267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, S. Essential oils: Their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods—A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 94, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baydar, H.; Sagdic, O.; Ozkan, G.; Karadogan, T. Antibacterial activity and composition of essential oils from Origanum, Thymbra and Satureja species with commercial importance in Turkey. Food Control 2004, 15, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivropoulou, A.; Papanikolaou, E.; Nikolaou, C.; Kokkini, S.; Lanaras, T.; Arsenakis, M. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of Origanum essential oils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1996, 44, 1202–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorianopoulos, N.; Evergetis, E.; Mallouchos, A.; Kalpoutzakis, E.; Nychas, G.-J.; Haroutounian, S.A. Seasonal variation in the chemical composition of the essential oils of Satureja species and their MIC assays against foodborne pathogens. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 3139–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Sanchez, P.M.; Nováková, A.; Bastian, F.; Alabouvette, C.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. Use of biocides for the control of fungal outbreaks in subterranean environments: The case of the Lascaux Cave in France. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 3762–3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyzik, A.; Ciuchcinski, K.; Dziurzynski, M.; Dziewit, L. The Bad and the Good—Microorganisms in Cultural Heritage Environments—An Update on Biodeterioration and Biotreatment Approaches. Materials 2021, 14, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Code | Essential Oil | Locality | Part Distilled | Ref. 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Salvia triloba | Rethymno, Creta | Aerial parts | [51] |

| B | Foeniculum vulgare | Astros, Peloponnese | Aerial parts | [52] |

| C | Satureja thymbra | Parnonas, Peloponnese | Aerial parts | [52] |

| D | Juniperus phoenicea | Antikyra, Central Greece | Berry reap crushed | [54] |

| E | Juniperus drupacea | Antikyra, Central Greece | Berry reap crushed | [54] |

| F | Juniperus drupacea | Antikyra, Central Greece | Berry reap crushed | [54] |

| G | Citrus x paradisii | Argolida, Peloponnese | By-products during Fruit liquidization | [53] |

| H | Citrus x paradisii | Argolida, Peloponnese | By-products during Fruit liquidization-Fragment 1 | [53] |

| I | Citrus limon | Argolida, Peloponnese | By-products during Fruit liquidization | [53] |

| J | Citrus reticulata | Argolida, Peloponnese | By-products during Fruit liquidization | [53] |

| K | Citrus reticulata | Argolida, Peloponnese | By-products during Fruit liquidization-Fragment 1 | [53] |

| L | Citrus sinensis | Argolida, Peloponnese | By-products during Fruit liquidization | [53] |

| M | Juniperus phoenicea | Antikyra, Central Greece | Berry reap crushed | [54] |

| N | Citrus limon | Corinthos, Peloponnese | Fruit Unreap | [53] |

| O | Citrus aurantium | Corinthos, Peloponnese | Fruit Reap | [53] |

| P | Laurus nobilis | Chania, Creta | Leaves | [51] |

| Q | Origanum vulgare wild | Kozani, North Greece | Aerial parts | [51] |

| R | Origanum vulgare | Kilkis, North Greece | Aerial parts | [52] |

| Isolate | Isolate with the Same Phenotype | Essential oil ( Inhibitory Concentration % v/v) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | ||

| Bacillus sp. R1P2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Bacillus mycoides R1P3 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Bacillus sp. R1P4 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Bacillus thuringiensis R1P5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Bacillus sp. R1P6 | R1P8, R1P9, R1P10 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Bacillus sp. R2P1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Bacillus sp. R2P3 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Bacillus sp. R2P4 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Bacillus sp. R2P5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Achromobacter sp. R1R18 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Achromobacter sp. R1R21 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Achromobacter sp. R1P1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Achromobacter sp. S1P1 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Achromobacter sp. S1P3 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Achromobacter sp. BP3 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Achromobacter sp. S2P2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Achromobacter sp. S2P3 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Achromobacter sp. S2P4 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Sinorhizobium (Ensifer) adhaerens R1R20 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Sinorhizobium (Ensifer) adhaerens R1R22 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Sinorhizobium sp. R2R10 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Sinorhizobium sp. BP4 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Paenibacillus sp./wynii/graminis S2P5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Paenibacillus sp. R2P2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Paenibacillus amylolyticus BP5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Paenibacillus sp. BP6 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Rhodococcus erythropolis S1P2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Rhodococcus sp. S2P6 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Rhodococcus sp. S2P7 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Rhodococcus sp. S2P8 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Stenotrophomonas sp. S1P4 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Stenotrophomonas sp. S2P9 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Isolate | Isolate with the Same Phenotype | Essential Oil ( Inhibitory Concentration % v/v) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | ||

| Penicillium vulpinum R1R3 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Penicillium sp. R1R5 | R1R11, R1R12 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Penicillium sp. R1R6 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Penicillium sp. S1R5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Penicillium sp. S1R6 | S1R2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Penicillium sp. S2R1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Clonostachys sp. R1R7 | R1R1, R1R4, R1R8 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Clonostachys sp. S1R1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Fusarium solani R2R5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Fusarium solani R2R8 | R2R4 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Fusarium sp. R2R11 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Doratomyces stemonitis R2R3 | R2R12, R2R14, R2S2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Cephalotrichum verrucisporum/oligotriphicum R2R1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Cephalotrichum sp. R1R2 | R1R9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Talaromyces minioluteus R2R7 | R2R2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Acremonium persicinum R2S1 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 0.2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Xenoacremonium falcatus R1R15 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Trichurus sp. R1S1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Cladosporium sp. BP1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Essential Oil | Inhibitory Concentration (% v/v) | Growth Inhibition (No of Isolates) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi (n = 31) | Bacteria (n = 35) | Total (n = 66) | |||

| A | Salvia triloba | 1.0 | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| B | Foeniculum vulgare | 1.0 | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| C | Satureja thymbra | 0.1 | 8 | 35 | 43 |

| 0.2 | 18 | 0 | 18 | ||

| 0.5 | 5 | 0 | 5 | ||

| Total | 31 | 35 | 66 | ||

| D | Juniperus phoenicea | 1.0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| E | Juniperus drupacea | 1.0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| F | Juniperus drupacea | 1.0 | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| G | Citrus x paradisii | 1.0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| H | Citrus x paradisii | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| I | Citrus limon | 1.0 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| J | Citrus reticulate | 1.0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| K | Citrus reticulate | 1.0 | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| L | Citrus sinensis | 1.0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| M | Citrus sinensis | 1.0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| N | Citrus limon | 1.0 | 16 | 16 | 32 |

| O | Citrus aurantium | 1.0 | 6 | 5 | 11 |

| P | Laurus nobilis | 0.5 | 19 | 7 | 26 |

| 1.0 | 0 | 12 | 12 | ||

| Total | 19 | 19 | 38 | ||

| Q | Origanum vulgare (wild) | 0.1 | 31 | 35 | 66 |

| R | Origanum vulgare | 0.1 | 31 | 35 | 66 |

| Origanum vulgare (R) | Satureja thymbra (C) | Origanum vulgare wild (Q) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC | NIC | MIC | NIC | MIC | NIC | |

| Bacillus sp. RIP4 | 0.069 ± 0.002 | 0.053 ± 0.001 | 0.135 ± 0.003 | 0.091 ± 0.001 | 0.015 ± 0.004 | 0.005 ± 0.002 |

| Stenotrophomonas sp. S2P9 | 0.071 ± 0.003 | 0.016 ± 0.004 | 0.157 ± 0.002 | 0.038 ± 0.001 | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 0.004 ± 0.001 |

| Paenibacillus sp. R2P2 | 0.041 ± 0.001 | 0.009 ± 0.001 | 0.074 ± 0.002 | 0.021 ± 0.001 | 0.039 ± 0.003 | 0.018 ± 0.002 |

| Paenibacillus sp. BP6 | 0.051 ± 0.003 | 0.028 ± 0.002 | 0.152 ± 0.003 | 0.069 ± 0.002 | 0.088 ± 0.002 | 0.032 ± 0.001 |

| Fusarium sp. R2R11 | 0.097 ± 0.010 | 0.027 ± 0.007 | 0.013 ± 0.010 | 0.027 ± 0.007 | 0.079 ± 0.009 | 0.016 ± 0.005 |

| Penicillium sp. R1R6 | 0.145 ± 0.009 | 0.035 ± 0.006 | 0.156 ± 0.008 | 0.038 ± 0.008 | 0.083 ± 0.008 | 0.018 ± 0.003 |

| Clonostachys sp. S1R1 | 0.103 ± 0.008 | 0.031 ± 0.009 | 0.106 ± 0.009 | 0.028 ± 0.004 | 0.072 ± 0.010 | 0.016 ± 0.005 |

| Cladosporium sp. BP1 | 0.101 ± 0.011 | 0.038 ± 0.008 | 0.064 ± 0.007 | 0.017 ± 0.005 | 0.054 ± 0.011 | 0.015 ± 0.002 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Argyri, A.A.; Doulgeraki, A.I.; Varla, E.G.; Bikouli, V.C.; Natskoulis, P.I.; Haroutounian, S.A.; Moulas, G.A.; Tassou, C.C.; Chorianopoulos, N.G. Evaluation of Plant Origin Essential Oils as Herbal Biocides for the Protection of Caves Belonging to Natural and Cultural Heritage Sites. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9091836

Argyri AA, Doulgeraki AI, Varla EG, Bikouli VC, Natskoulis PI, Haroutounian SA, Moulas GA, Tassou CC, Chorianopoulos NG. Evaluation of Plant Origin Essential Oils as Herbal Biocides for the Protection of Caves Belonging to Natural and Cultural Heritage Sites. Microorganisms. 2021; 9(9):1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9091836

Chicago/Turabian StyleArgyri, Anthoula A., Agapi I. Doulgeraki, Eftychia G. Varla, Vasiliki C. Bikouli, Pantelis I. Natskoulis, Serkos A. Haroutounian, Georgios A. Moulas, Chrysoula C. Tassou, and Nikos G. Chorianopoulos. 2021. "Evaluation of Plant Origin Essential Oils as Herbal Biocides for the Protection of Caves Belonging to Natural and Cultural Heritage Sites" Microorganisms 9, no. 9: 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9091836

APA StyleArgyri, A. A., Doulgeraki, A. I., Varla, E. G., Bikouli, V. C., Natskoulis, P. I., Haroutounian, S. A., Moulas, G. A., Tassou, C. C., & Chorianopoulos, N. G. (2021). Evaluation of Plant Origin Essential Oils as Herbal Biocides for the Protection of Caves Belonging to Natural and Cultural Heritage Sites. Microorganisms, 9(9), 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9091836